Anemia

From Nwe

From Nwe |

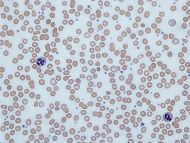

Human blood from a case of iron-deficiency anemia |

|

|---|---|

| ICD-10 | D50-D64 |

| ICD-O: | |

| ICD-9 | 280-285 |

| OMIM | {{{OMIM}}} |

| MedlinePlus | 000560 |

| eMedicine | med/132 |

| DiseasesDB | 663 |

Anemia (American English) or anaemia (British English), from the Greek (Ἀναιμία) meaning "without blood," refers to a deficiency of red blood cells (RBCs) and/or hemoglobin. This results in a reduced ability of blood to transfer oxygen to the tissues, causing hypoxia (state of low oxygen levels). Anemia is the most common disorder of the blood. In the United States, one-fifth of all females of childbearing age are affected by anemia.

Since all human cells depend on oxygen for survival, varying degrees of anemia can have a wide range of clinical consequences. Hemoglobin, the oxygen-carrying protein in the red blood cells, has to be present to ensure adequate oxygenation of all body tissues and organs.

The three main classes of anemia include:

- excessive blood loss, such as a hemorrhage or chronically through low-volume loss

- excessive blood cell destruction, known as hemolysis

- deficient red blood cell production, which is referred to as ineffective hematopoiesis

In menstruating women, dietary iron deficiency is a common cause of deficient red blood cell production. Thus, personal responsibility for one's diet is an important consideration, with consumption of food rich in iron essential to prevention of iron deficiency anemia.

Signs, symptoms, diagnosis, and treatment

Anemia goes undetected in many people and symptoms can be vague. Most commonly, people with anemia report a feeling of weakness or fatigue. People with more severe anemia sometimes report shortness of breath. Very severe anemia prompts the body to compensate by markedly increasing cardiac output, leading to palpitations (irregular and/or forceful beating of the heart) and sweatiness; this process can lead to heart failure in elderly people.

Pallor (pale skin and mucosal linings) is only notable in cases of severe anemia and is therefore not a reliable sign.

The only way to diagnose most cases of anemia is with a blood test. Generally, clinicians order a full blood count. Apart from reporting the number of red blood cells and the hemoglobin level, the automatic counters also measure the size of the red blood cells by flow cytometry, which is an important tool in distinguishing between the causes of anemia. A visual examination of a blood smear can also be helpful and is sometimes a necessity in regions of the world where automated analysis is less accessible.

In modern counters, four parameters (RBC Count, hemoglobin concentration, MCV, and red blood cell distribution width) are measured, allowing other parameters (hematocrit, mean corpuscular hemoglobin, and mean corpuscular hemoglobin concentration) to be calculated and then compared to values adjusted for age and sex. For human males, the hemoglobin level that is suggestive of anemia is usually less than 13.0 g/dl, and for females, it is less than 12.0 g/dl.

Depending on the clinical philosophy, whether the hospital's automated counter can immediately add it to the initial tests, and the clinicians' attitudes towards ordering tests, a reticulocyte count may be ordered either as part of the initial workup or during followup tests. This is a nearly direct measure of the bone marrow's capacity to produce new red blood cells, and is thus the most used method of evaluating the problem of production. This can be especially important in cases where both loss and a production problem may co-exist. Many physicians use the reticulocyte production index, which is a calculation of the ratio between the level of anemia and the extent to which the reticulocyte count has risen in response. Even in cases where an obvious source of loss exists, this index helps evaluate whether the bone marrow will be able to compensate for the loss and at what rate.

When the cause is not obvious, clinicians use other tests to further distinguish the cause for anemia. These are discussed with the differential diagnosis below. A clinician may also decide to order other screening blood tests that might identify the cause of fatigue; serum glucose, erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), ferritin (an iron-containing protein complex), serum iron, folate/RBC folate level, serum vitamin B12, renal (kidney) function tests (e.g. serum creatinine) and electrolytes may be part of such a workup.

There are many different treatments for anemia, including increasing dietary intake of readily available iron and iron supplementation. Treatment is determined by the type of anemia that is diagnosed. In severe cases of anemia, a blood transfusion may be necessary.

Types of anemia

There are several kinds of anemia produced by a variety of underlying causes. Anemia can be classified in a variety of ways. For instance, it can be classified based on the morphology of red blood cells, the underlying etiologic mechanisms, and/or the discernible clinical spectra, to mention a few.

Different clinicians approach anemia in different ways. Two major approaches of classifying anemias include the "kinetic" approach, which involves evaluating production, destruction, and loss, and the "morphologic" approach, which groups anemia by red blood cell size. The morphologic approach uses the quickly available and cheap Mean Corpuscular Volume, or MCV, test as its starting point. On the other hand, focusing early on the question of production (e.g., via the reticulocyte count of the kinetic approach) may allow the clinician more rapidly to expose cases where multiple causes of anemia coexist. Regardless of one's philosophy about the classification of anemia, however, any methodical clinical evaluation should yield equally good results.

The "kinetic" approach to anemia yields what many argue is the most clinically relevant classification of anemia. This classification depends on evaluation of several hematological parameters, particularly the blood reticulocyte (precursor of mature RBCs) count. This then yields the classification of defects by decreased red blood cell production, increased destruction, or blood loss.

In the morphological approach, anemia is classified by the size of red blood cells; this is either done automatically or on microscopic examination of a peripheral blood smear. The size is reflected in the mean corpuscular volume (MCV). If the cells are smaller than normal (under 80 femtoliter (fl), the anemia is said to be microcytic; if they are normal size (80-100 fl), normocytic; and if they are larger than normal (over 100 fl), the anemia is classified as macrocytic. This scheme quickly exposes some of the most common causes of anemia. For instance, a microcytic anemia is often the result of iron deficiency. In clinical workup, the MCV will be one of the first pieces of information available; so even among clinicians who consider the "kinetic" approach more useful philosophically, morphology will remain an important element of classification and diagnosis.

Other characteristics visible on the peripheral smear may provide valuable clues about a more specific diagnosis; for example, abnormal white blood cells may point to a cause in the bone marrow.

Microcytic anemia

- Iron deficiency anemia is the most common type of anemia overall, and it is often hypochromic microcytic. Iron deficiency anemia is caused when the dietary intake or absorption of iron is insufficient. Iron is an essential part of hemoglobin, and low iron levels result in decreased incorporation of hemoglobin into red blood cells. In the United States, 20 percent of all women of childbearing age have iron deficiency anemia, compared with only 2 percent of adult men.

The principal cause of iron deficiency anemia in premenopausal women is blood lost during menses. Studies have shown that iron deficiency without anemia causes poor school performance and lower IQ in teenage girls. In older patients, iron deficiency anemia is often due to bleeding lesions of the gastrointestinal tract; fecal occult blood testing, upper endoscopy, and colonoscopy are often performed to identify bleeding lesions, which can be malignant.

Iron deficiency is the most prevalent deficiency state on a worldwide basis. Iron deficiency affects women from different cultures and ethnicities. Iron found in animal meats are more easily absorbed by the body than iron found in non-meat sources. In countries where meat consumption is not as common, iron deficiency anemia is six to eight times more prevalent than in North America and Europe. A characteristic of iron deficiency is angular cheilitis, which is an abnormal fissuring of the angular sections (corners of the mouth) of the lips.

- Hemoglobinopathies- much rarer (apart from communities where these conditions are prevalent)

- Sickle-cell disease- inherited disorder in which red blood cells have an abnormal type of hemoglobin

- Thalassemia- hereditary condition in which part of hemoglobin is lacking; classified as either alpha or beta thalassemia

Microcytic anemia is primarily a result of hemoglobin synthesis failure/insufficiency, which could be caused by several etiologies:

- Heme synthesis defect

- Iron deficiency

- Anemia of Chronic Disorders (which, sometimes, is grouped into normocytic anemia)

- Globin synthesis defect

- alpha-, and beta-thalassemia

- HbE syndrome

- HbC syndrome

- and various other unstable hemoglobin diseases

- Sideroblastic defect

- Hereditary Sideroblastic anemia

- Acquired Sideroblastic anemia, including lead toxicity

- Reversible Sideroblastic anemia

A mnemonic commonly used to remember causes of microcytic anemia is TAILS: T - Thalassemia, A - Anemia of chronic disease, I - Iron deficiency anemia, L - Lead toxicity associated anemia, S - Sideroblastic anemia.

Normocytic anemia

Macrocytic anemia

- Megaloblastic anemia is due to a deficiency of either Vitamin B12 or folic acid (or both) due either to inadequate intake or insufficient absorption. Folate deficiency normally does not produce neurological symptoms, while B12 deficiency does. Symptoms of vitamin B12 deficiency include having a smooth, red tongue. Megaloblastic anemia is the most common cause of macrocytic anemia.

- Pernicious anemia is an autoimmune condition directed against the parietal cells of the stomach. Parietal cells produce intrinsic factor, required to absorb vitamin B12 from food. Therefore, the destruction of the parietal cells causes a lack of intrinsic factor, leading to poor absorption of vitamin B12.

- Alcoholism

- Methotrexate, zidovudine, and other drugs that inhibit DNA replication can also cause macrocytic anemia. This is the most common etiology in nonalcoholic patients.

Macrocytic anemia can be further divided into "megaloblastic anemia" or "non-megaloblastic macrocytic anemia." The cause of megaloblastic anemia is primarily a failure of DNA synthesis with preserved RNA synthesis, which result in restricted cell division of the progenitor cells. Progenitor cells are made in the bone marrow and travel to areas of blood vessel injury to help repair damage. The megaloblastic anemias often present with neutrophil (type of white blood cell) hypersegmentation (6-10 lobes). The non-megaloblastic macrocytic anemias have different etiologies (i.e. there is unimpaired DNA synthesis) which occur, for example, in alcoholism.

The treatment for vitamin B12-deficient macrocytic and pernicious anemias was first devised by the scientist William Murphy. He bled dogs to make them anemic and then fed them various substances to see what, if anything, would make them healthy again. He discovered that ingesting large amounts of liver seemed to cure the disease. George Richards Minot and George Whipple then set about to chemically isolate the curative substance and ultimately were able to isolate the vitamin B12 from the liver. For this, all three shared the 1934 Nobel Prize in Medicine.

Dimorphic anemia

In dimorphic anemia, two types of anemia are simultaneously present. For example, macrocytic hypochromic anemia can be due to hookworm infestation, leading to deficiency of both iron and vitamin B12 or folic acid, or following a blood transfusion.

Specific Anemias

- Fanconi anemia is an hereditary disease featuring aplastic anemia and various other abnormalities

- Hemolytic anemia causes a separate constellation of symptoms (also featuring jaundice and elevated lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) levels) with numerous potential causes. It can be autoimmune (when body attacks self), immune, hereditary, or mechanical (e.g. heart surgery). It can result (because of cell fragmentation) in a microcytic anemia, a normochromic anemia, or (because of premature release of immature RBCs from the bone marrow)in a macrocytic anemia.

- Hereditary spherocytosis is a hereditary disease that results in defects in the RBC cell membrane, causing the erythrocytes to be sequestered and destroyed by the spleen. This leads to a decrease in the number of circulating RBCs and, hence, anemia.

- Sickle-cell anemia, a hereditary disorder, is due to the presence of the mutant hemoglobin S gene.

- Warm autoimmune hemolytic anemia is an anemia caused by autoimmune attack against red blood cells, primarily by IgG (most common type of antibody)

- Cold Agglutinin hemolytic anemia is primarily mediated by IgM (type of antibody that reacts to blood group antigens)

Possible Complications

Anemia diminishes the capability of affected individuals to perform physical labor. This is a result of muscles being forced to depend on anaerobic metabolism (when not enough or no oxygen is available for use in metabolism).

The lack of iron associated with anemia can cause many complications, including hypoxemia, brittle or rigid fingernails, cold intolerance, impaired immune function, and possible behavioral disturbances in children. Hypoxemia (lack of oxygen in cells) resulting from anemia can worsen the cardio-pulmonary status of patients with pre-existing chronic pulmonary disease. Brittle or rigid fingernails may be a result of abnormal thinness of nails due to insufficient iron supply. Cold intolerance occurs in 20 percent of patients with iron deficiency anemia and it becomes visible through numbness and tingling. Impaired immune functioning leading to increased likelihood of sickness is another possible complication.

Finally, chronic anemia may result in behavioral disturbances in children as a direct result of impaired neurological development in infants and reduced scholastic performance in children of school age. Behavioral disturbances may even surface as an attention deficit disorder.

Anemia during pregnancy

Anemia affects 20 percent of all females of childbearing age in the United States. Because of the subtlety of the symptoms, women are often unaware that they have this disorder, as they attribute the symptoms to the stresses of their daily lives. Possible problems for the fetus include increased risk of growth retardation, prematurity, stillbirth (also called intrauterine death), rupture of the amnion, and infection.

During pregnancy, women should be especially aware of the symptoms of anemia, as an adult female loses an average of two milligrams of iron daily. Therefore, she must intake a similar quantity of iron in order to make up for this loss. Additionally, a woman loses approximately 500 milligrams of iron with each pregnancy, compared to a loss of 4-100 milligrams of iron with each period. Possible consequences for the mother include cardiovascular symptoms, reduced physical and mental performance, reduced immune function, tiredness, reduced peripartal blood reserves, and increased need for blood transfusion in the postpartum period.

Diet and Anemia

Consumption of food rich in iron is essential to prevention of iron deficiency anemia; however, the average adult has approximately nine years worth of B12 stored in the liver, and it would take four to five years of an iron-deficient diet to create iron-deficiency anemia from diet alone.

Iron-rich foods include:

- red meat

- green, leafy vegetables

- dried beans

- dried apricots, prunes, raisins, and other dried fruits

- almonds

- seaweeds

- parsley

- whole grains

- yams (vegetable)

In extreme cases of anemia, researchers recommend consumption of beef liver, lean meat, oysters, lamb or chicken, or iron drops may be introduced. Certain foods have been found to interfere with iron absorption in the gastrointestinal tract, and these foods should be avoided. They include tea, coffee, wheat bran, rhubarb, chocolate, soft drinks, red wine, and ice cream. With the exception of milk and eggs, animal sources of iron provide iron with better bioavailability than vegetable sources.

References

ISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Breymann, C. 2002. "Iron deficiency and anemia in pregnancy: Modern aspects of diagnosis and therapy." Blood Cells, Molecules, and Diseases 29(3):506-516.

- Conrad, M. E. 2006. Iron deficiency anemia. EMedicine from WEB-MD. Retrieved November 8, 2007.

- Raymond, T. 1999. "Anemia: Diagnosis, treatment, and prevention." Midwifery Today May 31, 1999.

- Scrimshaw, N. 1991. "Iron deficiency." Scientific American (Oct. 1991): 46-52.

- Schier, S. L. 2005. Approach to the adult patient with anemia. Up-to-Date (accessed in Jan 2006)

- Silverthorn, D. 2004. Human Physiology, An Integrated Approach, 3rd Edition. San Francisco: Benjamin Cummings. ISBN 9780805368512

- WHO Scientific Group on Nutritional Anaemias. 1968. Nutritional anaemias: report of a WHO scientific group. (meeting held in Geneva from 13 to 17 March 1967). World Health Organization. Geneva. Retrieved November 8, 2007.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.

↧ Download as ZWI file | Last modified: 02/04/2023 05:43:48 | 23 views

☰ Source: https://www.newworldencyclopedia.org/entry/Anemia | License: CC BY-SA 3.0

ZWI signed:

ZWI signed:

KSF

KSF