Federal Land Policy

From Ballotpedia

From Ballotpedia ![]() This Ballotpedia article is in need of updates. Please email us if you would like to suggest a revision. If you would like to help our coverage grow, consider donating to Ballotpedia.

This Ballotpedia article is in need of updates. Please email us if you would like to suggest a revision. If you would like to help our coverage grow, consider donating to Ballotpedia.

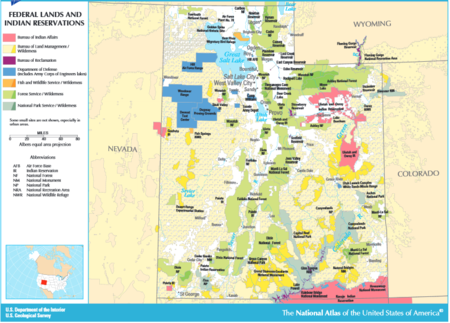

Federal land policy involves the acquisition, development, management, and conservation of land owned by the federal government on behalf of the American people. As of 2015, the federal government owned approximately 640 million acres of land (28 percent) of the 2.27 billion acres of land in the United States. Four federal agencies were responsible for managing between 608 million and 610 million acres (26 percent) of federal land. The remainder, approximately 14.4 million acres, was managed by other agencies and by the U.S. Department of Defense in the form of military and training bases. As of 2015, approximately 52 percent of federally owned acres were in 11 Western states and Alaska, 61 percent of which was federally owned land.[1]

Federal land policies govern the conservation of national parks, national forests, and forest reserves, recreation at national parks, oil and natural gas development, mineral extraction, wildlife and forest management, and grazing.[1]

Background[edit]

Overview[edit]

The United States federal government manages federal land on behalf of the American people. According to the U.S. Constitution, Congress has the power "to dispose of and make all needful Rules and Regulations respecting the Territory or other Property belonging to the United States." The federal government manages land for conservation, recreation, fish and wildlife protection, and natural resource development, including limited oil and natural gas development and timber production. As of 2015, the federal government owned between 635 million to 640 million acres (28 percent) of the estimated 2.27 billion acres in the United States. By comparison, the federal government owned 1.8 billion acres (79 percent) of land in the United States in 1867.[1][2]

Throughout the 19th century, the federal government transferred two-thirds of the 1.8 billion acres of federal land to individuals, state governments, corporations, and businesses to encourage land development and settlement. Since the beginning of the 20th century, federal lands have generally remained under federal ownership. In 1976, Congress passed the Federal Land Policy and Management Act, which declared that the remaining federal lands would stay under federal ownership.[1]

Federal agencies[edit]

Four federal agencies—the U.S. National Park Service (NPS), U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS), and U.S. Bureau of Land Management (BLM) within the U.S. Department of the Interior, and the U.S. Forest Service (USFS) in the U.S. Department of Agriculture—oversaw between 608 million and 610 million acres (95 percent) of federal land as of 2015. These agencies are described below:[1][3]

- The U.S. Forest Service, the oldest federal land agency, was established in 1905 to manage forest reserves (later known as national forests). Prior to 1905, forest reserves were managed by the U.S. Department of the Interior. As of 2015, the Forest Service managed 193 million acres of land, including 155 national forests, primarily in the West. Additionally, the Forest Service managed approximately 75 percent of all federal land in the Eastern United States. At its inception, the service managed national forests primarily to conserve land, preserve water flows, and produce timber. Following the Multiple Use Sustained Yield Act of 1960, the service began managing national forests for recreation, livestock grazing, and fish and wildlife habitat protection.

- The U.S. Bureau of Land Management (BLM) was established in 1947. As of 2015, the agency managed the most onshore federal lands of any agency (247 million acres). Approximately 99 percent of BLM-managed land was in 11 Western states and Alaska, which contained 29 percent of all BLM-managed land. BLM lands are managed according to a multiple-use management policy as established by the Federal Land Policy and Management Act of 1976. Multiple-use management is "management of public lands and their various resource values so that they are utilized in the combination that will best meet the present and future needs of the American people." Sustained yield is defined as "the achievement and maintenance in perpetuity of a high-level annual or regular periodic output of the various renewable resources of the public lands consistent with multiple use." By contrast, the National Park Service manages land primarily for conservation and recreation and is not governed by a multiple-use policy. BLM land is used for recreation, conservation, energy development (including oil and natural gas production, grazing, and timber harvesting.

- The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS) manages land primarily to conserve plants and animals, including endangered species. The agency's activities are governed by a primary-use policy in which the priority is to conserve animal and plant species and their habitat; other land uses, such as recreation, timber production, and oil and gas production, are permitted to the extent that they are compatible with plant and animal conservation. The Fish and Wildlife Service also enforces the federal Endangered Species Act. As of 2015, the agency was responsible for managing 89 million acres of federal land, 77 million acres (86 percent) of which were in Alaska.

- The U.S. National Park Service (NPS) was established in 1916 to manage park units established by Congress and national monuments established by the president. The Park Service is governed by a dual mission to preserve natural resources and to provide public access to them. It manages all U.S. national park units, which include natural areas (such as Yellowstone and the Grand Canyon), unique prehistoric sites, notable areas in American history (such as Gettysburg National Military Park), and recreational areas (such as the Santa Monica Mountains National Recreation Area). As of 2015, the service managed 80 million acres of land and 417 park units.

Federal land in each state[edit]

The table below shows each state's total acreage, the amount of federal land in each state (in acres), and the percentage of land in each state that is owned by the federal government. As of 2015 Alaska contained the most federal land (223.8 million acres) while Nevada contained the largest percentage of land owned by the federal government (84.9 percent). By contrast, Rhode Island and Connecticut had the fewest acres of federal land: 5,157 acres and 8,752 acres, respectively. Connecticut and Iowa tied for the lowest percentage of land owned by the federal government at 0.3 percent each.[1]

| Federal land ownership by state (as of 2015) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| State | Federal land acreage | Total state acreage | Percentage of federal land |

| Alabama | 844,026 | 32,678,400 | 2.6% |

| Alaska | 223,803,098 | 365,481,600 | 61.2% |

| Arizona | 28,064,307 | 72,688,000 | 38.6% |

| Arkansas | 3,151,685 | 33,599,360 | 9.4% |

| California | 45,864,800 | 100,206,720 | 45.8% |

| Colorado | 23,870,652 | 66,485,760 | 35.9% |

| Connecticut | 8,752 | 3,135,360 | 0.3% |

| Delaware | 29,864 | 1,265,920 | 2.4% |

| Florida | 4,599,919 | 34,721,280 | 13.2% |

| Georgia | 1,474,225 | 37,295,360 | 4.0% |

| Hawaii | 820,725 | 4,105,600 | 20.0% |

| Idaho | 32,621,631 | 52,933,120 | 61.6% |

| Illinois | 411,387 | 35,795,200 | 1.1% |

| Indiana | 384,365 | 23,158,400 | 1.7% |

| Iowa | 122,076 | 35,860,480 | 0.3% |

| Kansas | 272,987 | 52,510,720 | 0.5% |

| Kentucky | 1,094,036 | 25,512,320 | 4.3% |

| Louisiana | 1,325,780 | 28,867,840 | 4.6% |

| Maine | 211,125 | 19,847,680 | 1.1% |

| Maryland | 197,894 | 6,319,360 | 3.1% |

| Massachusetts | 61,802 | 5,034,880 | 1.2% |

| Michigan | 3,633,323 | 36,492,160 | 10.0% |

| Minnesota | 3,491,586 | 51,205,760 | 6.8% |

| Mississippi | 1,546,433 | 30,222,720 | 5.1% |

| Missouri | 1,635,122 | 44,248,320 | 3.7% |

| Montana | 27,003,251 | 93,271,040 | 29.0% |

| Nebraska | 546,759 | 49,031,680 | 1.1% |

| Nevada | 59,681,502 | 70,264,320 | 84.9% |

| New Hampshire | 798,718 | 5,768,960 | 13.8% |

| New Jersey | 179,374 | 4,813,440 | 3.7% |

| New Mexico | 26,981,490 | 77,766,400 | 34.7% |

| New York | 104,590 | 30,680,960 | 0.3% |

| North Carolina | 2,429,341 | 31,402,880 | 7.7% |

| North Dakota | 1,736,611 | 44,452,480 | 3.9% |

| Ohio | 305,641 | 26,222,080 | 1.2% |

| Oklahoma | 701,365 | 44,087,680 | 1.6% |

| Oregon | 32,614,185 | 61,598,720 | 52.9% |

| Pennsylvania | 617,339 | 28,804,480 | 2.1% |

| Rhode Island | 5,157 | 677,120 | 0.8% |

| South Carolina | 846,420 | 19,374,080 | 4.4% |

| South Dakota | 2,642,601 | 48,881,920 | 5.4% |

| Tennessee | 1,273,175 | 26,727,680 | 4.8% |

| Texas | 2,998,280 | 168,217,600 | 1.8% |

| Utah | 34,202,920 | 52,696,960 | 64.9% |

| Vermont | 464,644 | 5,936,640 | 7.8% |

| Virginia | 2,514,596 | 25,496,320 | 9.9% |

| Washington | 12,176,293 | 42,693,760 | 28.5% |

| West Virginia | 1,133,587 | 15,410,560 | 7.4% |

| Wisconsin | 1,793,100 | 35,011,200 | 5.1% |

| Wyoming | 30,013,219 | 62,343,040 | 48.1% |

| United States total | 623,313,931 | 2,271,343,360 | 27.4% |

| Source: U.S. Congressional Research Service, "Federal Land Ownership: Overview and Data" | |||

Changes to federal land (1990-2013)[edit]

The federal government owned around 23.5 million fewer acres in 2013 than in 1990, a 3.8 percent decrease.[1]

The map below details changes to federal land ownership between 1990 and 2013. Iowa saw the largest percentage increase in federal land—a 72.8 percent increase from 1990. New York saw a decrease of 106 percent from 1990 to 2013—215,441 acres compared to 104,590 acres—the largest percentage decrease.

Payments in lieu of taxes[edit]

- See also: Payments in lieu of taxes

Local governments receive payments from the U.S. Department of the Interior to offset lost property tax revenue from non-taxable federal land within their boundaries—these payments are known as payments in lieu of taxes or PILTs. The Interior Department issues payments for all tax-exempt land managed by the U.S. Bureau of Land Management, the U.S. National Park Service, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, and the U.S. Forest Service. PILTs are also made for federal water projects and select military installations. The payments are calculated based on population and the amount of federal land within an affected area.[4]

The table below shows the amount paid by the federal government to local governments in the form of PILTs between fiscal years 2014 and 2017. California received the most in PILTs for 2017—$48.2 million. Rhode Island did not receive any PILTs in 2017, while Connecticut received the least—$31,769 for 2017.[4]

| Payments in Lieu of Taxes (PILTs) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| State | FY 2017 | FY 2016 | FY 2015 | FY 2014 | |

| Alabama | $715,833 | $1,182,129 | $1,131,049 | $1,023,078 | |

| Alaska | $29,695,460 | $28,961,235 | $28,482,595 | $28,548,370 | |

| Arizona | $36,023,640 | $35,022,842 | $34,413,828 | $34,497,956 | |

| Arkansas | $7,014,950 | $6,764,645 | $6,350,722 | $6,340,600 | |

| California | $48,261,603 | $47,273,144 | $45,793,923 | $45,298,833 | |

| Colorado | $36,618,440 | $35,558,866 | $33,583,582 | $34,530,642 | |

| Connecticut | $31,769 | $31,078 | $30,521 | $30,934 | |

| Delaware | $80,265 | $78,944 | $77,946 | $77,446 | |

| Florida | $5,583,600 | $5,334,721 | $5,271,756 | $5,311,455 | |

| Georgia | $2,641,630 | $2,585,621 | $2,512,499 | $2,450,254 | |

| Hawaii | $360,118 | $352,278 | $345,119 | $349,305 | |

| Idaho | $30,054,704 | $29,370,334 | $28,609,614 | $28,579,192 | |

| Illinois | $1,314,809 | $1,210,908 | $1,189,351 | $1,181,018 | |

| Indiana | $600,320 | $579,706 | $564,001 | $545,278 | |

| Iowa | $507,815 | $496,761 | $485,690 | $491,294 | |

| Kansas | $1,218,747 | $1,192,534 | $1,171,638 | $1,183,003 | |

| Kentucky | $2,549,650 | $2,359,304 | $2,146,228 | $2,182,678 | |

| Louisiana | $1,050,340 | $785,240 | $1,074,521 | $638,198 | |

| Maine | $328,222 | $309,738 | $313,804 | $316,231 | |

| Maryland | $111,289 | $108,237 | $106,398 | $108,292 | |

| Massachusetts | $104,726 | $113,605 | $111,640 | $118,864 | |

| Michigan | $4,644,847 | $4,829,985 | $4,646,379 | $4,611,245 | |

| Minnesota | $1,922,431 | $2,239,153 | $2,181,150 | $2,181,242 | |

| Mississippi | $2,130,234 | $1,988,191 | $1,833,943 | $1,825,109 | |

| Missouri | $4,036,144 | $3,748,511 | $3,695,781 | $3,477,166 | |

| Montana | $31,786,271 | $30,285,246 | $29,259,009 | $28,809,242 | |

| Nebraska | $1,184,648 | $1,076,611 | $1,062,481 | $1,053,278 | |

| Nevada | $26,184,790 | $25,632,826 | $25,244,861 | $25,439,484 | |

| New Hampshire | $1,898,963 | $1,911,880 | $1,885,851 | $1,908,034 | |

| New Jersey | $114,446 | $112,002 | $103,186 | $104,096 | |

| New Mexico | $38,525,087 | $37,770,954 | $37,466,124 | $37,677,905 | |

| New York | $147,017 | $161,618 | $159,770 | $160,767 | |

| North Carolina | $4,482,979 | $4,339,384 | $4,233,041 | $4,242,457 | |

| North Dakota | $1,624,414 | $1,529,161 | $1,523,807 | $1,525,912 | |

| Ohio | $696,303 | $674,635 | $655,758 | $600,939 | |

| Oklahoma | $3,303,313 | $3,133,183 | $3,053,052 | $3,042,242 | |

| Oregon | $19,653,568 | $18,435,896 | $17,716,801 | $17,680,594 | |

| Pennsylvania | $1,132,363 | $1,072,646 | $984,917 | $801,459 | |

| Rhode Island | $0 | $0 | $0 | $0 | |

| South Carolina | $719,218 | $643,746 | $598,646 | $575,919 | |

| South Dakota | $6,584,778 | $6,298,544 | $6,203,105 | $6,313,000 | |

| Tennessee | $2,370,775 | $2,212,059 | $2,140,169 | $2,121,952 | |

| Texas | $5,310,455 | $5,207,842 | $5,095,121 | $5,220,394 | |

| Utah | $39,500,105 | $38,362,447 | $37,619,551 | $37,903,225 | |

| Vermont | $1,066,058 | $1,045,492 | $1,009,992 | $1,019,729 | |

| Virginia | $3,996,099 | $3,891,567 | $3,740,282 | $3,614,508 | |

| Washington | $21,312,109 | $20,497,977 | $19,509,154 | $19,272,636 | |

| West Virginia | $3,206,308 | $3,113,365 | $3,082,021 | $3,108,857 | |

| Wisconsin | $3,520,577 | $3,443,993 | $3,376,781 | $1,600,968 | |

| Wyoming | $28,605,863 | $28,198,773 | $27,171,270 | $27,143,411 | |

| United States total | $464,600,000 | $451,600,000 | $439,084,000 | $436,904,919 | |

| Source: U.S. Department of the Interior | |||||

Grazing[edit]

Grazing policy[edit]

The U.S. Bureau of Land Management (BLM) and the U.S. Forest Service charge ranchers annual fees to graze livestock on federal lands. The federal grazing fee was $2.11 per animal unit month (AUM) in 2016. An AUM is "the amount of forage needed to sustain one cow, five sheep, or five goats for a month." As of 2016, the BLM managed livestock grazing on 155 million acres of land and oversaw more than 18,000 leases and permits for livestock grazing. Permits and leases are valid for 10 years. In fiscal year 2015, the BLM spent $36.2 million on livestock grazing administration, including permits issuances and land evaluations; the agency also collected $14.5 million in grazing fees. Between 1954 and 2013, grazing on federal lands declined from 18.2 million AUMs to 7.9 million AUMs.[5][6][7]

Discussion of grazing on federal lands focuses on the costs and benefits of federal land grazing to ranchers and the federal government. Different views on this issue are summarized below:

- The Public Lands Council, whose stated mission is to represent "cattle and sheep producers who hold public lands grazing permits", argued in 2015 that federal land ranching produces benefits for the land itself and for the federal government. Ranchers that graze livestock on federal land save the Bureau of Land Management approximately $750 million each year by maintaining the lands, according to the organization. The council further argued that ranching on grazed land costs the BLM $2 per acre compared to $5 per acre for ungrazed land. The council credited these cost savings to ranchers’ land activities, including preserving waterways, controlling invasive species, and first responding to wildfires.[8]

- In a March 2015 report published by the Property and Environment Research Center, whose stated mission is "improving environmental quality through property rights and markets", Holly Fretwell and Shawn Regan argued that federal expenses related to grazing are high and federal revenues are low compared to state governments and state-owned lands. The authors found that the Forest Service and Bureau of Land Management generated 10 cents and 14 cents, respectively, for every dollar spent on rangeland management, including grazing management, compared to state-owned trust lands. The authors concluded this data should prompt debate over whether grazing policy should remain a federal responsibility.[9]

- In a February 2016 article at the Center for Western Priorities, whose stated mission is "to protect land, water, and communities in the American West", Lucy Livesay argued that ranchers pay significantly less to graze on federal lands compared to state-owned and private land in the Western United States. Livesay cited the 2016 federal fee of $2.11 per month compared to nine Western states, all of which had fees between $3 and $20 per month. Livesay further argued that private lands in Western states had lease rates between 4 times and 11 times the federal fee.[10]

Conservation[edit]

Background[edit]

Historically, federal lands were held to increase the federal government's stature, to promote settlement and development in the West, and to raise revenue for various national, state, and local needs, such as schools, defense, and transportation. During the 1800s, federal land laws were passed either to preserve land, sell it to raise revenue or to promote transportation, or otherwise dispose of it for settlement and economic development. Congress during the 19th century authorized the disposal of federal lands to private citizens, states, and companies and businesses for development. Some lands were sold to pay soldiers or to reduce the national debt. Congress passed the Homestead Act of 1862 to encourage settlement in the Western United States. The act provided settlers with 160 acres of federal land in exchange for a filing fee and five years of continuous residence. After five years, settlers received ownership.[1][11]

Congress also passed conservation laws between 1870 and 1920. In 1872, the Yellowstone Public Park Act set apart land near the Yellowstone River for a public park, establishing Yellowstone National Park as the first national park in the United States. In 1891, President Benjamin Harrison (R) signed the Forest Reserve Act. The law established the National Forest System and allowed the president to designate land as publicly owned forest reserves. President Theodore Roosevelt (R) used the Forest Reserve Act to increase U.S. forest reserves by approximately 40 million acres (1.7 percent of the 2.27 billion acres of land in the United States).

The Antiquities Act of 1906 allowed the president the power to issue proclamations restricting the use of certain federal lands and to establish national monuments on federal land. National monuments are conserved in the same way as national parks, which are managed for conservation purposes and to provide public access and recreation. The act was passed following acts of looting on antiquated and prehistoric lands in the Western United States. The National Park Service Act of 1916 established the U.S. National Park Service, which initially managed 35 national parks and monuments. The act required the service to "to conserve the scenery and the natural and historic objects and the wildlife therein and to provide for the enjoyment of the same in such manner and by such means as will leave them unimpaired for the enjoyment of future generations."[12][13][14][15][16]

Wilderness Act[edit]

The first version of the Wilderness Act of 1964 was drafted by Howard Zahniser, a former U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service employee and member of the Wilderness Society. The stated purpose of the legislation was to conserve portions of remaining wilderness areas in the United States that were not already federally owned and managed. The Wilderness Act passed the U.S. Senate in 1961 by a vote of 73-12. The U.S. House voted for the bill by a vote of 374-1, and President Lyndon Johnson (D) signed the bill into law on September 3, 1964.[18][19][20][21][22]

The Wilderness Act established the National Wilderness Preservation System, a system of federally preserved wilderness areas. The act prohibited certain activities in a wilderness area, such as mechanized and motorized vehicle use, timber harvesting, grazing, mining, and other kinds of development. In addition, the act allowed Congress to designate, remove, or modify the status of wilderness areas based on the following criteria:[23][24]

- A wilderness area must be at least 5,000 acres or of sufficient size that the area can be preserved in an unimpaired condition.

- Areas must have an unnoticeable human presence.

- Wilderness areas must have "ecological, geological, or other features of scientific, educational, scenic, or historical value."

Maintenance[edit]

Background[edit]

According to the Congressional Research Service in March 2017, the four main federal land management agencies face deferred maintenance (also known as a maintenance backlog), which includes land and/or infrastructure maintenance that was not done when scheduled or planned. The maintenance was thus deferred to an unknown future period. Recreation sites, buildings, roads, and trails are the most common infrastructure in need of maintenance. The total amount of federal funding provided for the maintenance backlog each year is unknown since such funding is not identified in either presidential budget requests or congressional appropriations documents. The table below show total deferred maintenance cost estimates for the four federal agencies.[25]

| Total deferred maintenance costs for federal land management agencies (as of fiscal year 2016) | |

|---|---|

| Federal agency | Total maintenance backlog |

| U.S. Forest Service | $5.49 billion |

| U.S. National Park Service | $10.9 billion |

| U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service | $1.4 billion |

| U.S. Bureau of Land Management | $810 million |

| Total | $18.6 billion |

| Source: U.S. Congressional Research Service, "Federal Land Ownership: Overview and Data" | |

Addressing deferred maintenance[edit]

Views differ on how to address the maintenance backlog; whether funding for maintenance projects should be increased; or whether funds from other programs should be used to address the backlog. These views are summarized below:

- In a June 2015 article, Reed Watson and Scott Wilson of the Property and Environment Research Center (PERC), whose stated mission is "improving environmental quality through property rights and markets", argued for user fees to address deferred maintenance costs. The authors argued that the federal government's acquisition of more land argue that the maintenance backlog is evidence of federal land mismanagement and that existing funds should be diverted to maintain existing federal land.[26]

- In a December 2013 op-ed, Sen. Lisa Murkowski (R-Alaska) argued for using funds from the Land and Water Conservation Fund (LWCF), which is used to acquire additional federal land, to address the maintenance backlog. Murkowski further argued that expanding private donations to national parks and introducing entrance fees for parks that do not require a fee could raise funds to address maintenance issues.[27]

- In an article titled Help Fix the National Park Service Repair Backlog, the National Parks Conservation Association, whose stated mission is "to protect and enhance national parks", argued that Congress has not appropriated funding to address maintenance costs and that Congress should increase funding to address the backlog.

- According to the Center for Western Priorities, whose stated mission is "to protect land, water, and communities in the American West", federal budget cuts are responsible for failure to address maintenance needs on federal land and that Congress should pass increased funding for the maintenance backlog.[28][27][29][30][31]

Acquisition[edit]

Background[edit]

In 1965, Congress established the Land and Water Conservation Fund (LWCF), a program for the federal government to purchase private land for public uses, such as recreation and conservation. The LWCF is the principal funding source for federal land management agencies to acquire additional land. The LWCF has been used to acquire areas such as Harpers Ferry National Historical Park in West Virginia, Big Cypress National Preserve in Florida, and Mount Rainier National Park in Washington. In addition to federal land acquisition, the LWCF is used for recreation and conservation projects at the federal and state levels and for matching grants to states for land acquisition and outdoor recreation projects.[32]

Congress determines LWCF funding for the program each year; the fund also collects royalties from offshore oil and natural gas development. Between 1965 and 2014, oil and gas royalty revenue for the fund totaled around $36 billion, while Congress authorized $16.8 billion in funding during that period. Of Congress' total funding for the LWCF from 1964-2014, 62 percent went toward federal land purchases, and 25 percent and 13 percent went toward state recreational programs and other purposes (such as wildlife grants and county payments), respectively. Of the LWCF's total funding in fiscal year 2014, $180 million (58.8 percent) went toward federal land acquisition, $48 million (15.6 percent) went toward state grants, and $78 million (25.4 percent) went toward other purposes.[32]

Land acquisition and funding[edit]

Discussion of the LWCF involves the purpose of the program and appropriate levels of funding. Differing viewpoints on the LWCF are summarized below:

- In September 2015, House Natural Resources Committee Chairman Rob Bishop (R-Utah) argued that the LWCF should not reauthorized unless it is used for its original purpose of funding state and local recreational and conservation projects. Bishop further argued that the federal government uses the LWCF to acquire more land at the expense of other land management priorities, such as deferred maintenance work, and that the funding should be limited to those projects, rather than land acquisitions. "Any reauthorization of [the Land and Water Conservation Fund] will, among other improvements, prioritize local communities as originally intended," Bishop argued.[33][34][32]

- In his April 2015 testimony to the U.S. House on the LWCF, Shawn Regan, a research fellow at the Property and Environment Research Center, whose stated mission is "improving environmental quality through property rights and markets", argued that the fund should not be used for additional land acquisitions but to address existing maintenance costs. Regan argued, "Congress should require that the LWCF be used to reduce the massive backlog of deferred maintenance projects on existing federal lands before it can be used to acquire new federal lands." According to Regan, the fund should instead be used for wastewater system repairs, infrastructure and building repairs, campground maintenance, and other maintenance projects. [35][36]

- In April 2015, House Natural Resources Committee Ranking Member Rep. Raul Grijalva (D-Ariz.) argued that the LWCF be permanently funded and not subject to the annual appropriations process due to its importance in financing state and local land projects. Grijalva argued, "Conserving land for future generations is one of our government’s primary responsibilities to the American people. ... Drawing out the uncertainty over the program's funding every few years serves no one, especially when our constituents so strongly believe in the LWCF’s mission and value to the country."[37]

- A May 2017 article published by the LWCF Coalition, a group affiliated with the Wilderness Society, whose stated mission is "to protect wilderness and inspire Americans to care for our wild places", argued that projects on federal land funded by the LWCF support local tourism and recreation industries. The article's authors argued that visits to federal lands supported by the LWCF contributed approximately $44 billion in economic activity and supported over 388,000 jobs in 2010. The authors further argued that federal land acquisition in 2010 contributed $442 million in economic activity at a cost of $214 million.[38]

Energy[edit]

Background[edit]

The federal government allows oil and natural gas development on federal land. Approximately 166 million acres (26 percent) of all federal land can be leased to private individuals and companies for energy development, including drilling for crude oil and natural gas, generating solar energy, mining for coal and geothermal energy.[39]

Production on federal land[edit]

In 2014, the United States produced 148,802 thousand barrels of oil and 2,499,845 million cubic feet of natural gas on federal land.[40]

Between 2009 and 2014, oil production on federal land rose 29.8 percent—from 104,525 thousand barrels of oil in 2009 to 148,802 thousand barrels of oil in 2014. During the same period, natural gas production on federal land fell 27.8 percent—from 3,196,473 million cubic feet of natural gas in 2009 to 2,499,845 million cubic feet of natural gas in 2014.[40][41][42]

The map below shows oil and natural gas production on federal land in 2014. Production was concentrated in Western states and several Midwestern and Southern states, such as North Dakota and Texas.

New Mexico led in oil production on federal land while Wyoming led in natural gas production on federal land in 2014.

Land transfers[edit]

Background[edit]

As of 2015, federal land transfers to state governments, particularly in the Western United States, were discussed in 10 Western state legislatures. A proponent of transferring federal land ownership to the states is the American Lands Council, a Utah-based group whose stated mission is "to secure local control of western public lands by transferring federal public lands to willing States." In 2012, the group's founder, Utah Rep. Ken Ivory (R), introduced the Utah Transfer of Public Lands Act, which was passed by the Utah State Legislature and signed by Gov. Gary Herbert (R). The law declared that the federal government should transfer over 20 million acres of federal land to the state. From 2012 to 2015, 10 Western states considered legislation on federal land transfers to the states.[43]

Support and opposition[edit]

Proponents of the transfers argue that states and localities have greater knowledge of local areas and are able to manage federal land more effectively than the federal government. Proponents argue that state governments manage their own land more efficiently and cost-effectively than the federal government manages federal land. According to a March 2015 study by the Property and Environment Research Center (PERC), whose stated mission is "improving environmental quality through property rights and markets", the transfer of federal land to individual state ownership would produce more revenue for state governments, though "states are not guaranteed to become better land stewards than the federal government if they are burdened by similar regulations and restrictions as federal land agencies."[44]

Opponents of the transfers argue that the economic costs of state ownership outweigh the costs of federal land ownership. According to the Center for Western Priorities, whose stated mission is "to protect land, water, and communities in the American West", state governments are unable to cover the costs of managing federal land unless they privatize the land, raise taxes, or use state funds designated for other purposes. The organization cited a January 2014 study by economists from the University of Utah and Utah State University on the Utah Transfer of Public Lands Act, which found that transferring federal land in Utah to the state would only be economically feasible if gas and oil prices remained stable and that the transfer would cost the state $245 million annually.[45]

State action[edit]

In March 2016, the Utah Legislature authorized $14 million in funding to legally challenging the federal government's land ownership in the state. The legislation "strongly encourages" the state executive branch to use all legislative and legal efforts to transfer federal land to the state government. The legislation also stated that the legislature and governor should file a lawsuit in the U.S. Supreme Court no later than December 2017 if other efforts fail. Governor Gary Herbert (R) said he supports a legal challenge against the federal government.[46][47]

The table below shows the federal land transfer bills that were proposed, passed, or tabled in Western state legislatures as of November 2015.[43][48][49][50][51][52][53][54]

| State legislation addressing federal land transfer (as of November 2015) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| State | Legislation | Year introduced | Purpose | Status (as of November 2015) |

| Arizona | House Bill 2658 | 2015 | Create a group to study federal land transfer to the state | Passed and signed by governor |

| Colorado | Senate Bill 232 | 2015 | Create a group to study federal land transfer to the state | Failed in state Senate |

| Idaho | House Bill 265 | 2015 | Create a group to study federal land transfer to the state | Failed in state Senate |

| Montana | House Bill 496 | 2015 | Create a group to study federal land management | Vetoed by governor |

| Nevada | Senate Joint Resolution 1 | 2015 | Request Congress to transfer federal land to the state | Passed in both state chambers |

| New Mexico | House Bill 291 | 2015 | Create a group to study federal land transfer to the state | Failed in state House committee |

| Oregon | House Bill 3240 | 2015 | Create a group to study federal land transfer to the state | No legislative action in 2015 |

| Utah | House Bill 148 | 2012 | Require the federal government to transfer land to state government | Passed and signed by governor |

| Washington | Senate Bill 5405 | 2015 | Create a group to study federal land transfer to the state | No legislative action in 2015 |

| Wyoming | Senate File 56 | 2015 | Create a group to study federal land transfer to the state | Passed in state House |

Recent news[edit]

The link below is to the most recent stories in a Google news search for the terms Federal land United States. These results are automatically generated from Google. Ballotpedia does not curate or endorse these articles.

See also[edit]

- Federal land ownership by state

- Federal land policy in the states

- U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service

- U.S. Bureau of Land Management

- U.S. Forest Service

Footnotes[edit]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 1.6 1.7 U.S. Congressional Research Service, "Federal Land Ownership: Overview and Data" accessed December 15, 2015 Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; name "CRSoverview" defined multiple times with different content - ↑ Federal Archives, "Text of the U.S. Constitution," accessed November 17, 2014

- ↑ U.S. Congressional Research Service, "Federal Lands and Natural Resources: Overview and Selected Issues for the 113th Congress," December 8, 2014

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 U.S. Department of the Interior, "PILT," accessed October 4, 2014

- ↑ U.S. Bureau of Land Management, "Livestock Grazing on Public Lands," accessed October 6, 2014

- ↑ U.S. Bureau of Land Management, "Rangeland Program Glossary," March 4, 2011

- ↑ U.S. Bureau of Land Management, "Fact Sheet on the BLM’s Management of Livestock Grazing," March 28, 2014

- ↑ Public Lands Council, "The Value of Ranching," accessed August 1, 2017

- ↑ Property and Environment Research Center, "Divided Lands: State vs. Federal Management in the West," March 2015

- ↑ Center for Western Priorities, "This is Why Most Western Ranchers Won’t Support States Seizing U.S. Public Lands," February 11, 2016

- ↑ Public Lands Foundation, "America's public lands: Origin, history, future," accessed September 20, 2016

- ↑ Library of Congress, "The Evolution of the Conservation Movement, 1850-1920," accessed February 3, 2015

- ↑ Teaching American History, "The Early Conservation Movement," accessed February 3, 2015

- ↑ ForestHistory.org, "Reserve Act and Congress: Passage of the 1891 Act," accessed February 3, 2015

- ↑ PBS.org, "Theodore Roosevelt (1858-1919)," accessed February 3, 2015

- ↑ United States Library of Congress, "Documentary Chronology of Selected Events in the Development of the American Conservation Movement, 1847-1920," accessed September 26, 2016

- ↑ The Wilderness Society, "Wilderness Act," accessed October 21, 2016

- ↑ Govtrack.us, "H.R. 9070. Establish a National Wilderness Preservation System. Passage," accessed February 16, 2015

- ↑ Smithsonian.com, "How the Wilderness Act Was Passed," accessed February 9, 2015

- ↑ PBS.org, "Wilderness Act Overview," accessed February 9, 2015

- ↑ Brigham Young University Law Review, "The Wilderness Act of 1964: Where We Do We Go From Here?" October 1, 1975

- ↑ Colorado Public Radio, "Wilderness Act: 50 Years Ago, Colorado Was At The Heart Of A Wild Fight," August 28, 2014

- ↑ Congressional Research Service, "Wilderness Laws: Statutory Provisions and Prohibited and Permitted Uses," February 22, 2011

- ↑ Wilderness.net, "The Wilderness Act of 1964," accessed January 26, 2015

- ↑ U.S. Congressional Research Service, "Federal Lands and Natural Resources: Overview and Selected Issues for the 113th Congress," December 8, 2014

- ↑ Property and Environment Research Center, "Let's Fix Our National Parks, Not Add More," June 30, 2015

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 The Hill, "We need new ways to fund our national parks," December 3, 2013

- ↑ Center for Western Priorities, "As Americans Head to Public Lands This Summer, Some Politicians Continue Mistaken Logic of Plundering the Land and Water Conservation Fund," accessed July 1, 2017

- ↑ The New York Times, "Let’s Fix Our National Parks, Not Add More," June 30, 2015

- ↑ National Parks Conservation Association, "Our Values," accessed November 12, 2015

- ↑ Center for Western Priorities, "As Americans Head to Public Lands This Summer, Some Politicians Continue Mistaken Logic of Plundering the Land and Water Conservation Fund," accessed July 1, 2017

- ↑ 32.0 32.1 32.2 U.S. Congressional Research Service, "Land and Water Conservation Fund: Overview, Funding History, and Issues," October 21, 2014

- ↑ U.S. House Natural Resources Committee, "Bishop: Special Interests Will Not Prevent Congress from Modernizing LWCF, Protecting State and Local Recreational Access," September 25, 2015

- ↑ U.S. House Natural Resources Committee, "PARC Act," accessed November 23, 2015

- ↑ Property and Environment Research Center, "Reforming the Land and Water Conservation Fund for the 21st Century," April 22, 2015

- ↑ The Hill, "Why the Land and Water Conservation Fund needs to be reformed," September 24, 2015

- ↑ U.S. House Natural Resources Committee Democrats, "Ranking Member Grijalva, Rep. Fitzpatrick Introduce Bill to Permanently Establish Land and Water Conservation Fund, Prevent Sept. Expiration," April 14, 2015

- ↑ LWCF Coalition, "Ranking Member Grijalva, Rep. Fitzpatrick Introduce Bill to Permanently Establish Land and Water Conservation Fund, Prevent Sept. Expiration," April 15, 2015

- ↑ Office of Natural Resource Revenue, "Statistical Information," accessed October 11, 2015

- ↑ 40.0 40.1 Office of Natural Resource Revenue, "Statistical Information," accessed October 11, 2015

- ↑ eia.gov, "Petroleum and Other Liquids," accessed July 23, 2016

- ↑ eia.gov, "Natural Gas," accessed July 23, 2016

- ↑ 43.0 43.1 High Country News, "State bills to study federal-to-state land transfers," April 30, 2015

- ↑ Property and Environment Research Center, "Divided Lands: State vs. Federal Management in the West," accessed November 21, 2015

- ↑ Salt Lake City Tribune, "Economist: Transferring federal lands could generate revenue for Utah," December 1, 2014

- ↑ E&E News, "Utah prepares war chest for takeover lawsuit," March 11, 2016

- ↑ BNA.com, "Utah Governor Backs Lawsuit Over Federal Land Management," March 14, 2016

- ↑ Arizona Capitol Times, "Gov. Doug Ducey vetoes measures to take over federal land," April 14, 2015

- ↑ Colorado Wildlife Federation, "CO Sen. Bill 15-232 defeated in Senate on narrow vote," April 29, 2015

- ↑ The Spokesman-Review, "Some states say no to federal land transfer bills," May 6, 2015

- ↑ Las Vegas Review-Journal, "Nevada Legislature approves resolution urging transfer of federal lands," May 18, 2015

- ↑ New Mexico Legislature, "2015 Regular Session - HB 291," accessed November 22, 2015

- ↑ Oregon State Legislature, "2015 Regular Session HB 3240," accessed November 24, 2015

- ↑ TrackBill.com, "WY - SF56 Study on transfer of public lands," accessed November 24, 2015

Categories: [Public policy concepts and issues] [One-off pages, mothballed]

↧ Download as ZWI file | Last modified: 03/06/2026 10:02:13 | 14 views

☰ Source: https://ballotpedia.org/Federal_land_policy | License: CC BY-SA 3.0

KSF

KSF