-

Ice cap at top of Puncak Jaya in Papua (1972).

-

Autumn in the Blue Mountains, New South Wales.

-

A tropical rainforest in Papua New Guinea.

-

Simpson desert in Northern Territory.

-

Monsoonal squall in Darwin.

-

A billabong in the Kakadu National Park, Northern Territory. The monsoon climate of northern Australia is hot and humid in summer.

-

Snow in Jindabyne, New South Wales, a town in the Snowy Mountains.

-

Grassland in Queensland with mountains in background.

-

Spring in the apple orchards of Tasmania.

Australia (Continent)

From Handwiki

From Handwiki

.svg.png) | |

| Area | 8,600,000 km2 (3,300,000 sq mi) (7th) |

|---|---|

| Population | 39,357,469[note 1] (6th) |

| Population density | 4.2/km2 (11/sq mi) |

| Demonym | Australian/Papuan |

| Countries | |

| Dependencies | External (2)

Internal (2)

|

| Languages | English, Indonesian, Tok Pisin, Hiri Motu, 269 indigenous Papuan and Austronesian languages, and about 70 Indigenous Australian languages |

| Time zones | UTC+8, UTC+9:30, UTC+10 |

| Internet TLD | .au, .id, and .pg |

| Largest cities | |

The continent of Australia, sometimes known in technical contexts by the names Sahul (/səˈhuːl/), Australia-New Guinea, Australinea, or Meganesia[citation needed] to distinguish it from the Australia , is located within the Southern and Eastern hemispheres.[1] The continent includes mainland Australia, Tasmania, the island of New Guinea (Papua New Guinea and Western New Guinea), the Aru Islands, the Ashmore and Cartier Islands, most of the Coral Sea Islands, and some other nearby islands. Situated in the geographical region of Oceania, Australia is the smallest of the seven traditional continents.

The continent includes a continental shelf overlain by shallow seas which divide it into several landmasses—the Arafura Sea and Torres Strait between mainland Australia and New Guinea, and Bass Strait between mainland Australia and Tasmania. When sea levels were lower during the Pleistocene ice age, including the Last Glacial Maximum about 18,000 BC, they were connected by dry land into the combined landmass of Sahul. The name "Sahul" derives from the Sahul Shelf, which is a part of the continental shelf of the Australian continent. During the past 18,000 to 10,000 years, rising sea levels overflowed the lowlands and separated the continent into today's low-lying arid to semi-arid mainland and the two mountainous islands of New Guinea and Tasmania.

With a total land area of 8.56 million square kilometres (3,310,000 sq mi), the Australian continent is the smallest, lowest, flattest, and second-driest continent (after Antarctica) on Earth.[2] As the country of Australia is mostly on a single landmass, and comprises most of the continent, it is sometimes informally referred to as an island continent, surrounded by oceans.[3]

Papua New Guinea, a country within the continent, is one of the most culturally and linguistically diverse countries in the world.[4] It is also one of the most rural, as only 18 percent of its people live in urban centres.[5] West Papua, a province of Indonesia, is home to an estimated 44 uncontacted tribal groups.[6] Australia, the largest landmass in the continent, is highly urbanised,[7] and has the world's 14th-largest economy with the second-highest human development index globally.[8][9] Australia also has the world's 9th largest immigrant population.[10][11]

Terminology

The continent of Australia is sometimes known by the names Sahul, Australinea, or Meganesia to distinguish it from the country of Australia, and consists of the landmasses which sit on Australia's continental plate. This includes mainland Australia, Tasmania, and the island of New Guinea, which comprises Papua New Guinea and Western New Guinea (Papua and West Papua, provinces of Indonesia).[12][13][14][15] The name "Sahul" takes its name from the Sahul Shelf, which is part of the continental shelf of the Australian continent.

The term Oceania, originally a "great division" of the world in the 1810s, was replaced in English language countries by the concept of Australia as one of the world's continents in the 1950s.[16] Prior to the 1950s, before the popularization of the theory of plate tectonics, Antarctica, Australia and Greenland were sometimes described as island continents, but none were usually taught as one of the world's continents in English-speaking countries.[17][18][16] Scottish cartographer John Bartholomew wrote in 1873 that, "the New World consists of North America, and the peninsula of South America attached to it. These divisions [are] generally themselves spoken as continents, and to them has been added another, embracing the large island of Australia and numerous others in the [Pacific] Ocean, under the name of Oceania. There are thus six great divisions of the earth — Europe, Asia, Africa, North America, South America and Oceania."[19]

The American author Samuel Griswold Goodrich wrote in his 1854 book History of All Nations that, "geographers have agreed to consider the island world of the Pacific Ocean as a third continent, under the name Oceania." In this book the other two continents were categorized as being the New World (consisting of North America and South America) and the Old World (consisting of Africa, Asia and Europe).[20] In his 1879 book Australasia, British naturalist Alfred Russel Wallace commented that, "Oceania is the word often used by continental geographers to describe the great world of islands we are now entering upon" and that "Australia forms its central and most important feature."[21] He did not explicitly label Oceania a continent in the book, but did note that it was one of the six major divisions of the world.[21] He considered it to encompass the insular Pacific area between Asia and the Americas, and claimed it extended up to the Aleutian Islands, which are among the northernmost islands in the Pacific Ocean.[21] However, definitions of Oceania varied during the 19th century. In the 19th century, many geographers divided up Oceania into mostly racially-based subdivisions; Australasia, Malaysia (encompassing the Malay Archipelago), Melanesia, Micronesia and Polynesia.[22]

Today, the Malay Archipelago is typically considered part of Southeast Asia, and the term Oceania is often used to denote the region encompassing the Australian continent, Zealandia and various islands in the Pacific Ocean that are not included in the seven-continent model. It has been recognized by the United Nations as one of the world's five major continental divisions since its foundation in 1947, along with Africa, Asia, Europe and the Americas.[23][24] The UN's definition of Oceania utilizes four of the five subregions from the 19th century; Australasia, Melanesia, Micronesia, and Polynesia. They include American Samoa, Australia and their external territories, the Cook Islands, the Federated States of Micronesia, French Polynesia, Fiji, Guam, Kiribati, the Marshall Islands, Nauru, New Caledonia, New Zealand, Niue, the Northern Mariana Islands, Palau, Papua New Guinea, Pitcairn Islands, Samoa, the Solomon Islands, Tokelau, Tonga, Tuvalu, Vanuatu, Wallis and Futuna, and the United States Minor Outlying Islands (Baker Island, Howland Island, Jarvis Island, Midway Atoll, Palmyra Atoll, and Wake Island).[25] The original UN definition of Oceania from 1947 included these same countries and semi-independent territories, which were mostly still colonies at that point.[26]

The island states of Indonesia, Japan , the Philippines , Singapore and Taiwan, all located within the bounds of the Pacific or associated marginal seas, are excluded from the UN definition. The states of Hong Kong and Malaysia, located in both mainland Asia and marginal seas of the Pacific, are also excluded, as is the nation of Brunei, which shares the island of Borneo with Indonesia and Malaysia. Further excluded are East Timor and Indonesian New Guinea/Western New Guinea, areas which are biogeographically or geologically associated with the Australian landmass.[27] This definition of Oceania is used in statistical reports, by the International Olympic Committee, and by many atlases.[28] The CIA World Factbook also categorize Oceania or the Pacific area as one of the world's major continental divisions, but use the term "Australia and Oceania" to refer to the area.[29] Their definition does not include Australia's subantarctic external territory Heard Island and McDonald Islands, but is otherwise the same as the UN definition, and it is also used for statistical purposes.

In countries such as Argentina , Brazil , China , Chile , Costa Rica, Ecuador, France , Greece, Italy, Mexico, the Netherlands, Peru, Spain , Switzerland or Venezuela, Oceania is treated as a continent in the sense that it is "one of the parts of the world", and Australia is only seen as an island nation. In other countries, including Kazakhstan, Norway , Poland and Russia , Australia and Eurasia are thought of as continents, while Asia, Europe and Oceania are regarded as "parts of the world".[30] In the Pacific Ocean Handbook (1945), author Eliot Grinnell Mears wrote that he categorized Australia, New Zealand and Pacific islands under the label of Oceania for "scientific reasons; Australia's fauna is largely continental in character, New Zealand's are clearly insular; and neither Commonwealth realm has close ties with Asia." He further added that, "the term Australasia is not relished by New Zealanders and this name is too often confused with Australia."[31] Some 19th century definitions of Oceania grouped Australia, New Zealand and the islands of Melanesia together under the label of Australasia, in other 19th century definitions of Oceania, the term was only used to refer to Australia itself, with New Zealand being categorized with the islands of Polynesia in such definitions.[32][22]

Archaeological terminology for this region has changed repeatedly. Before the 1970s, the single Pleistocene landmass was called Australasia, derived from the Latin australis, meaning "southern", although this word is most often used for a wider region that includes lands like New Zealand that are not on the same continental shelf. In the early 1970s, the term Greater Australia was introduced for the Pleistocene continent.[33] Then at a 1975 conference and consequent publication,[34] the name Sahul was extended from its previous use for just the Sahul Shelf to cover the continent.[33]

In 1984 W. Filewood suggested the name Meganesia, meaning "great island" or "great island-group", for both the Pleistocene continent and the present-day lands,[35] and this name has been widely accepted by biologists.[36] Others have used Meganesia with different meanings: travel writer Paul Theroux included New Zealand in his definition[37] and others have used it for Australia, New Zealand and Hawaii.[38] Another biologist, Richard Dawkins, coined the name Australinea in 2004.[39] Australia–New Guinea has also been used.[40]

Geology and geography

The Australian continent, being a part of the Indo-Australian Plate (more specifically, the Australian Plate), is the lowest, flattest, and oldest landmass on Earth[41] and it has had a relatively stable geological history. New Zealand is not part of the continent of Australia, but of the separate, submerged continent of Zealandia.[42] New Zealand and Australia are both part of the Oceanian sub-region known as Australasia, with New Guinea being in Melanesia.

The continent includes a continental shelf overlain by shallow seas which divide it into several landmasses—the Arafura Sea and Torres Strait between mainland Australia and New Guinea, and Bass Strait between mainland Australia and Tasmania. When sea levels were lower during the Pleistocene ice age, including the Last Glacial Maximum about 18,000 BC, they were connected by dry land. During the past 18,000[43] to 10,000 years, rising sea levels overflowed the lowlands and separated the continent into today's low-lying arid to semi-arid mainland and the two mountainous islands of New Guinea and Tasmania.[44] The continental shelf connecting the islands, half of which is less than 50 metres (160 ft) deep, covers some 2.5 million square kilometres (970,000 sq mi), including the Sahul Shelf[45][46] and Bass Strait.

Geological forces such as tectonic uplift of mountain ranges or clashes between tectonic plates occurred mainly in Australia's early history, when it was still a part of Gondwana. Australia is situated in the middle of the tectonic plate, and therefore currently has no active volcanism.[47]

The continent primarily sits on the Indo-Australian Plate. Because of its central location on its tectonic plate, Australia does not have any active volcanic regions, the only continent with this distinction.[48] The lands were joined with Antarctica as part of the southern supercontinent Gondwana until the plate began to drift north about 96 million years ago. For most of the time since then, Australia–New Guinea remained a continuous landmass. When the last glacial period ended in about 10,000 BC, rising sea levels formed Bass Strait, separating Tasmania from the mainland. Then between about 8,000 and 6,500 BC, the lowlands in the north were flooded by the sea, separating the Aru Islands, mainland Australia, New Guinea, and Tasmania.

A northern arc consisting of the New Guinea Highlands, the Raja Ampat Islands, and Halmahera was uplifted by the northward migration of Australia and subduction of the Pacific Plate. The Outer Banda Arc was accreted along the northwestern edge the continent; it includes the islands of Timor, Tanimbar, and Seram. Papua New Guinea has several volcanoes, as it is situated along the Pacific Ring of Fire. Volcanic eruptions are not rare, and the area is prone to earthquakes and tsunamis because of this.[49] Mount Wilhelm in Papua New Guinea is the second highest mountain in the continent,[50] and at 4,884 metres (16,024 ft) above sea level, Puncak Jaya is the highest mountain.

Human history

The Australian continent and Sunda were points of early human migrations after leaving Africa.[51] Recent research points to a planned migration of hundreds of people using bamboo rafts, which eventually landed on Sahul.[52][53][54]

Indigenous peoples

Indigenous Australians, that is Aboriginal Australians and Torres Strait Islanders people, are the original inhabitants of the Australian continent and nearby islands. They migrated from Africa to Asia around 70,000 years ago[55] and arrived in Australia at least 50,000 years ago, based on archaeological evidence.[56] More recent research points to earlier arrival, possibly 65,000 years ago.[57]

They are believed to be among the earliest human migrations out of Africa. There is evidence of genetic and linguistic interchange between Australians in the far north and the Austronesian peoples of modern-day New Guinea and the islands, but this may be the result of recent trade and intermarriage.[58] The earliest known human remains were found at Lake Mungo, a dry lake in the southwest of New South Wales.[59] Remains found at Mungo suggest one of the world's oldest known cremations, thus indicating early evidence for religious ritual among humans.[60] Dreamtime remains a prominent feature of Australian Aboriginal art, the oldest continuing tradition of art in the world.[61]

Papuan habitation is estimated to have begun between 42,000 and 48,000 years ago in New Guinea.[62] Trade between New Guinea and neighboring Indonesian islands was documented as early as the seventh century, and archipelagic rule of New Guinea by the 13th. At the beginning of the seventh century, the Sumatra-based empire of Srivijaya (7th century–13th century) engaged in trade relations with western New Guinea, initially taking items like sandalwood and birds-of-paradise in tribute to China, but later making slaves out of the natives.[63] The rule of the Java-based empire of Majapahit (1293–1527) extended to the western fringes of New Guinea.[64] Recent archaeological research suggests that 50,000 years ago people may have occupied sites in the highlands at New Guinean altitudes of up to 2,000 m (6,600 ft), rather than being restricted to warmer coastal areas.[65]

Pre-colonial history

Legends of Terra Australis Incognita—an "unknown land of the South"—date back to Roman times and before, and were commonplace in medieval geography, although not based on any documented knowledge of the continent.[66] Ancient Greek philosopher Aristotle speculated of a large landmass in the southern hemisphere, saying, "Now since there must be a region bearing the same relation to the southern pole as the place we live in bears to our pole...".[67] His ideas were later expanded by Ptolemy (2nd century AD), who believed that the lands of the Northern Hemisphere should be balanced by land in the south. The theory of balancing land has been documented as early as the 5th century on maps by Macrobius, who uses the term Australis on his maps.[68]

Terra Australis, a hypothetical continent first posited in antiquity, appeared on maps between the 15th and 18th centuries.[69] Scientists, such as Gerardus Mercator (1569)[70] and Alexander Dalrymple as late as 1767 argued for its existence, with such arguments as that there should be a large landmass in the south as a counterweight to the known landmasses in the Northern Hemisphere.[71] The cartographic depictions of the southern continent in the 16th and early 17th centuries, as might be expected for a concept based on such abundant conjecture and minimal data, varied wildly from map to map; in general, the continent shrank as potential locations were reinterpreted. At its largest, the continent included Tierra del Fuego, separated from South America by a small strait; New Guinea; and what would come to be called Australia.[72]

European exploration

In 1606 Dutch navigator Willem Janszoon made the first documented European sight and landing on the continent of Australia in Cape York Peninsula.[73] Dutch explorer Abel Janszoon Tasman circumnavigated and landed on parts of the Australia n continental coast and discovered Van Diemen's Land (now Tasmania), New Zealand in 1642, and Fiji islands.[74] He was the first known European explorer to reach these islands.[75]

In the quest for Terra Australis, Spanish explorations in the 17th century, such as the expedition led by the Portuguese navigator Pedro Fernandes de Queirós, discovered the Pitcairn and Vanuatu archipelagos, and sailed the Torres Strait between Australia and New Guinea, named after navigator Luís Vaz de Torres, who was the first European to explore the Strait. When Europeans first arrived, inhabitants of New Guinea and nearby islands, whose technologies included bone, wood, and stone tools, had a productive agricultural system. In 1660, the Dutch recognised the Sultan of Tidore's sovereignty over New Guinea. The first known Europeans to sight New Guinea were probably the Portuguese and Spanish navigators sailing in the South Pacific in the early part of the 16th century.

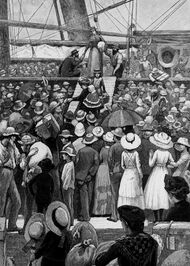

On 23 April 1770 British explorer James Cook made his first recorded direct observation of indigenous Australians at Brush Island near Bawley Point.[76] On 29 April, Cook and crew made their first landfall on the mainland of the continent at a place now known as the Kurnell Peninsula. It is here that James Cook made first contact with an Aboriginal tribe known as the Gweagal, who he fired upon, injuring one.[77] His expedition became the first recorded Europeans to have encountered the eastern coastline of Australia.[78] Captain Arthur Phillip led the First Fleet of 11 ships and about 850 convicts into Sydney on 26 January 1788.[79] This was to be the location for the new colony. Phillip described Sydney Cove as being "without exception the finest harbour in the world".[80]

Modern history

In 1883, the Colony of Queensland tried to annex the southern half of eastern New Guinea, but the British government did not approve.[81] The Commonwealth of Australia came into being when the Federal Constitution was proclaimed by the Governor-General, Lord Hopetoun, on 1 January 1901. From that point a system of federalism in Australia came into operation, entailing the establishment of an entirely new national government (the Commonwealth government) and an ongoing division of powers between that government and the States. With the encouragement of Queensland, in 1884, a British protectorate had been proclaimed over the southern coast of New Guinea and its adjacent islands. British New Guinea was annexed outright in 1888. The possession was placed under the authority of the newly federated Commonwealth of Australia in 1902 and with passage of the Papua Act of 1905, British New Guinea became the Australian Territory of Papua, with formal Australian administration beginning in 1906.[82]

The Bombing of Darwin on 19 February 1942 was the largest single attack ever mounted by a foreign power on Australia.[83] In an effort to isolate Australia, the Japanese planned a seaborne invasion of Port Moresby, in the Australian Territory of New Guinea. Between July and November 1942, Australian forces repulsed Japanese attempts on the city by way of the Kokoda Track, in the highlands of New Guinea. The Battle of Buna–Gona, between November 1942 and January 1943, set the tone for the bitter final stages of the New Guinea campaign, which persisted into 1945. The offensives in Papua and New Guinea of 1943–44 were the single largest series of connected operations ever mounted by the Australian armed forces.[84]

Following the 1998 commencement of reforms across Indonesia, Papua and other Indonesian provinces received greater regional autonomy. In 2001, "Special Autonomy" status was granted to Papua province, although to date, implementation has been partial and often criticised.[85] The region was administered as a single province until 2003, when it was split into the provinces of Papua and West Papua. Elections in 1972 resulted in the formation of a ministry headed by Chief Minister Michael Somare, who pledged to lead the country to self-government and then to independence. Papua New Guinea became self-governing on 1 December 1973 and achieved independence on 16 September 1975. The country joined the United Nations (UN) on 10 October 1975.[86]

Migration brought large numbers of southern and central Europeans to Australia for the first time. A 1958 government leaflet assured readers that unskilled non-British migrants were needed for "labour on rugged projects ...work which is not generally acceptable to Australians or British workers".[87] Australia fought on the side of Britain in the two world wars and became a long-standing ally of the United States when threatened by Imperial Japan during World War II. Trade with Asia increased and a post-war immigration program received more than 6.5 million migrants from every continent. Supported by immigration of people from more than 200 countries since the end of World War II, the population increased to more than 23 million by 2014.[88]

Ecology

Flora

For about 40 million years Australia–New Guinea was almost completely isolated. During this time, the continent experienced numerous changes in climate, but the overall trend was towards greater aridity. When South America eventually separated from Antarctica, the development of the cold Antarctic Circumpolar Current changed weather patterns across the world. For Australia–New Guinea, it brought a marked intensification of the drying trend. The great inland seas and lakes dried out. Much of the long-established broad-leaf deciduous forest began to give way to the distinctive hard-leaved sclerophyllous plants that characterise the modern Australian landscape.

Typical Southern Hemisphere flora include the conifers Podocarpus (eastern Australia and New Guinea), the rainforest emergents Araucaria (eastern Australia and New Guinea), Nothofagus (New Guinea and Tasmania) and Agathis (northern Queensland and New Guinea), as well as tree ferns and several species of Eucalyptus. Prominent features of the Australian flora are adaptations to aridity and fire which include scleromorphy and serotiny. These adaptations are common in species from the large and well-known families Proteaceae (Banksias and Grevilleas), Myrtaceae (Eucalyptus or gum trees, Melaleucas and Callistemons), Fabaceae (Acacias or wattles), and Casuarinaceae (Casuarinas or she-oaks), which are typically found in the Australian mainland. The flora of New Guinea is a mixture of many tropical rainforest species with origins in Asia, such as Castanopsis acuminatissima, Lithocarpus spp., elaeocarps, and laurels, together with typically Australasian flora. In the New Guinean highlands, conifers such as Dacrycarpus, Dacrydium, Papuacedrus and Libocedrus are present.[89]

For many species, the primary refuge was the relatively cool and well-watered Great Dividing Range. Even today, pockets of remnant vegetation remain in the cool uplands, some species not much changed from the Gondwanan forms of 60 or 90 million years ago. Eventually, the Australia–New Guinea tectonic plate collided with the Eurasian plate to the north. The collision caused the northern part of the continent to buckle upwards, forming the high and rugged mountains of New Guinea and, by reverse (downwards) buckling, the Torres Strait that now separates the two main landmasses. The collision also pushed up the islands of Wallacea, which served as island 'stepping-stones' that allowed plants from Southeast Asia's rainforests to colonise New Guinea, and some plants from Australia–New Guinea to move into Southeast Asia. The ocean straits between the islands were narrow enough to allow plant dispersal, but served as an effective barrier to exchange of land mammals between Australia–New Guinea and Asia.

Among the fungi, the remarkable association between Cyttaria gunnii (one of the "golf-ball" fungi) and its associated trees in the genus Nothofagus is evidence of that drift: the only other places where this association is known are New Zealand and southern Argentina and Chile .[90]

Fauna

Due to the spread of animals, fungi and plants across the single Pleistocene landmass the separate lands have a related biota.[91] There are over 300 bird species in West Papua, of which at least 20 are unique to the ecoregion, and some live only in very restricted areas. These include the grey-banded munia, Vogelkop bowerbird, and the king bird-of-paradise.[92]

Australia has a huge variety of animals; some 83% of mammals, 89% of reptiles, 24% of fish and insects and 93% of amphibians that inhabit the continent are endemic to Australia.[93] This high level of endemism can be attributed to the continent's long geographic isolation, tectonic stability, and the effects of an unusual pattern of climate change on the soil and flora over geological time. Australia and its territories are home to around 800 species of bird;[94] 45% of these are endemic to Australia.[95] Predominant bird species in Australia include the Australian magpie, Australian raven, the pied currawong, crested pigeons and the laughing kookaburra.[96] The koala, emu, platypus and kangaroo are national animals of Australia,[97] and the Tasmanian devil is also one of the well-known animals in the country.[98] The goanna is a predatory lizard native to the Australian mainland.[99]

As the continent drifted north from Antarctica, a unique fauna, flora and mycobiota developed. Marsupials and monotremes also existed on other continents, but only in Australia–New Guinea did they out-compete the placental mammals and come to dominate. New Guinea has 284 species and six orders of mammals: monotremes, three orders of marsupials, rodents and bats; 195 of the mammal species (69%) are endemic. New Guinea has a rich diversity of coral life and 1,200 species of fish have been found. Also about 600 species of reef-building coral—the latter equal to 75 percent of the world's known total. New Guinea has 578 species of breeding birds, of which 324 species are endemic. Bird life also flourished—in particular, the songbirds (order Passeriformes, suborder Passeri) are thought to have evolved 50 million years ago in the part of Gondwana that later became Australia , New Zealand, New Guinea, and Antarctica, before radiating into a great number of different forms and then spreading around the globe.[100]

Animal groups such as macropods, monotremes, and cassowaries are endemic to Australia. There were three main reasons for the enormous diversity that developed in animal, fungal and plant life.

- While much of the rest of the world underwent significant cooling and thus loss of species diversity, Australia–New Guinea was drifting north at such a pace that the overall global cooling effect was roughly equalled by its gradual movement toward the equator. Temperatures in Australia–New Guinea, in other words, remained reasonably constant for a very long time, and a vast number of different animal, fungal and plant species were able to evolve to fit particular ecological niches.

- Because the continent was more isolated than any other, very few outside species arrived to colonise, and unique native forms developed unimpeded.

- Finally, despite the fact that the continent was already very old and thus relatively infertile, there are dispersed areas of high fertility. Where other continents had volcanic activity and/or massive glaciation events to turn over fresh, unleached rocks rich in minerals, the rocks and soils of Australia–New Guinea were left largely untouched except by gradual erosion and deep weathering. In general, fertile soils produce a profusion of life, and a relatively large number of species/level of biodiversity. This is because where nutrients are plentiful, competition is largely a matter of outcompeting rival species, leaving great scope for innovative co-evolution as is witnessed in tropical, fertile ecosystems. In contrast, infertile soils tend to induce competition on an abiotic basis meaning individuals all face constant environmental pressures, leaving less scope for divergent evolution, a process instrumental in creating new species.

Although New Guinea is the most northerly part of the continent, and could be expected to be the most tropical in climate, the altitude of the New Guinea highlands is such that a great many animals and plants that were once common across Australia–New Guinea now survive only in the tropical highlands where they are severely threatened by population growth.

Climate

In New Guinea, the climate is mostly monsoonal (December to March), southeast monsoon (May to October), and tropical rainforest with slight seasonal temperature variation. In lower altitudes, the temperature is around 27 °C (81 °F) year round. But the higher altitudes, such as Mendi, are constantly around 21 °C (70 °F) with cool lows nearing 11 °C (52 °F), with abundant rainfall and high humidity. The New Guinea Highlands are one of the few regions close to the equator that experience snowfall, which occurs in the most elevated parts of the mainland. Some areas in the island experience an extraordinary amount of precipitation, averaging roughly 4,500 millimetres (180 in) of rainfall annually.

The Australian landmass's climate is mostly desert or semi-arid, with the southern coastal corners having a temperate climate, such as oceanic and humid subtropical climate in the east coast and Mediterranean climate in the west. The northern parts of the country have a tropical climate.[101] Snow falls frequently on the highlands near the east coast, in the states of Victoria, New South Wales, Tasmania and in the Australian Capital Territory. Temperatures in Australia have ranged from above 50 °C (122 °F) to well below 0 °C (32 °F). Nonetheless, minimum temperatures are moderated. The El Niño-Southern Oscillation is associated with seasonal abnormality in many areas in the world. Australia is one of the continents most affected and experiences extensive droughts alongside considerable wet periods.[102]

Demography

Religion

Christianity is the predominant religion in the continent, although large proportions of Australians belong to no religion.[103] Other religions in the region include Islam, Buddhism and Hinduism, which are prominent minority religions in Australia. Traditional religions are often animist, found in New Guinea. Islam is widespread in the Indonesian New Guinea.[104] Many Papuans combine their Christian faith with traditional indigenous beliefs and practices.[105]

Languages

"Aboriginal Australian languages", including the large Pama–Nyungan family, "Papuan languages" of New Guinea and neighbouring islands, including the large Trans–New Guinea family, and "Tasmanian languages" are generic terms for the native languages of the continent other than those of Austronesian family.[106] Predominant languages include English in Australia, Tok Pisin in Papua New Guinea, and Indonesian (Malay) in Indonesian New Guinea. Immigration to Australia have brought overseas languages such as Italian, Greek, Arabic, Filipino, Mandarin, Vietnamese and Spanish, among others.[107] Contact between Austronesian and Papuan resulted in several instances in mixed languages such as Maisin. Tok Pisin is an English creole language spoken in Papua New Guinea.[108] Papua New Guinea has more languages than any other country,[4] with over 820 indigenous languages, representing 12% of the world's total, but most have fewer than 1,000 speakers.[109]

Immigration

Since 1945, more than 7 million people have settled in Australia. From the late 1970s, there was a significant increase in immigration from Asian and other non-European countries, making Australia a multicultural country.[110] Sydney is the most multicultural city in Oceania, having more than 250 different languages spoken, with about 40 percent of residents speaking a language other than English at home.[111] Furthermore, 36 percent of the population reported having been born overseas, with top countries being Italy, Lebanon, Vietnam and Iraq, among others.[112][113] Melbourne is also fairly multicultural, having the largest Greek-speaking population outside of Europe,[114] and the second largest Asian population in Australia after Sydney.[115][116][117]

Economy

.jpg)

Australia is the only First World country on the Australia-New Guinea continent, although the economy of Australia is by far the largest and most dominant economy in the region and one of the largest in the world. Australia's per-capita GDP is higher than that of the United Kingdom , Canada , Germany , and France in terms of purchasing power parity.[120] The Australian Securities Exchange in Sydney is the largest stock exchange in Australia and in the South Pacific.[121] In 2012, Australia was the 12th largest national economy by nominal GDP and the 19th-largest measured by PPP-adjusted GDP.[122] Tourism in Australia is an important component of the Australian economy. In the financial year 2014/15, tourism represented 3.0% of Australia 's GDP contributing A$47.5 billion to the national economy.[123] In 2015, there were 7.4 million visitor arrivals.[124] Mercer Quality of Living Survey ranks Sydney tenth in the world in terms of quality of living,[125] making it one of the most livable cities.[126] It is classified as an Alpha+ World City by GaWC.[127][128] Melbourne also ranked highly in the world's most liveable city list,[129] and is a leading financial centre in the Asia-Pacific region.[130][131]

Papua New Guinea is rich in natural resources, which account for two-thirds of their export earnings. Though PNG is filled with resources, the lack of country's development led foreign countries to take over few sites and continued foreign demand for PNG's resources and as a result, the United States constructed an oil company and began to export in 2004 and this was the largest project in PNG's history.[132][133] Papua New Guinea is classified as a developing economy by the International Monetary Fund.[134] Strong growth in Papua New Guinea's mining and resource sector led to the country becoming the sixth fastest-growing economy in the world in 2011.[135][136]

Politics

Australia is a federal parliamentary constitutional monarchy[138] with Charles III at its apex as the King of Australia, a role that is distinct from his position as monarch of the other Commonwealth realms. The King is represented in Australia by the Governor-General at the federal level and by the Governors at the state level, who by convention act on the advice of his ministers.[139][140] There are two major political groups that usually form government, federally and in the states: the Australian Labor Party and the Coalition which is a formal grouping of the Liberal Party and its minor partner, the National Party.[141][142] Within Australian political culture, the Coalition is considered centre-right and the Labor Party is considered centre-left.[143]

Papua New Guinea is a Commonwealth realm. As such, King Charles III is its sovereign and head of state. The constitutional convention, which prepared the draft constitution, and Australia, the outgoing metropolitan power, had thought that Papua New Guinea would not remain a monarchy. The founders, however, considered that imperial honours had a cachet.[144] The monarch is represented by the Governor-General of Papua New Guinea, currently Bob Dadae. Papua New Guinea (along with Solomon Islands) is unusual among Commonwealth realms in that governors-general are elected by the legislature, rather than chosen by the executive branch.

Culture

Since 1788, the primary influence behind Australian culture has been Anglo-Celtic Western culture, with some Indigenous influences.[145][146][147] The divergence and evolution that has occurred in the ensuing centuries has resulted in a distinctive Australian culture.[148][149][150] Since the mid-20th century, American popular culture has strongly influenced Australia, particularly through television and cinema.[151][147] Other cultural influences come from neighbouring Asian countries, and through large-scale immigration from non-English-speaking nations.[151][147][152][153] The Australian Museum in Sydney and the National Gallery of Victoria in Melbourne are the oldest and largest museums in the continent, as well as in Oceania.[154][155] Sydney's New Year's Eve celebrations are the largest in the continent.[156]

It is estimated that more than 7000 different cultural groups exist in Papua New Guinea, and most groups have their own language. Because of this diversity, in which they take pride, many different styles of cultural expression have emerged; each group has created its own expressive forms in art, performance art, weaponry, costumes and architecture. Papua New Guinea is one of the few cultures in Oceania to practice the tradition of bride price.[157] In particular, Papua New Guinea is world-famous for carved wooden sculpture: masks, canoes, story-boards.

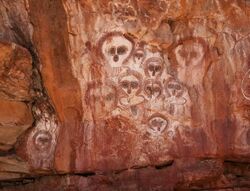

Australia has a tradition of Aboriginal art which is thousands of years old, the best known forms being rock art and bark painting. Evidence of Aboriginal art in Australia can be traced back at least 30,000 years.[158] Examples of ancient Aboriginal rock artworks can be found throughout the continent – notably in national parks such as those of the UNESCO listed sites at Uluru and Kakadu National Park in the Northern Territory, but also within protected parks in urban areas such as at Ku-ring-gai Chase National Park in Sydney.[159][160] Aboriginal culture includes a number of practices and ceremonies centered on a belief in the Dreamtime. Reverence for the land and oral traditions are emphasised.[161]

Sport

Popular sports in Papua New Guinea include various codes of football (rugby league, rugby union, soccer, and Australian rules football), cricket, volleyball, softball, netball, and basketball. Other Olympic sports are also gaining popularity, such as boxing and weightlifting. Rugby league is the most popular sport in Papua New Guinea (especially in the highlands), which also unofficially holds the title as the national sport.[163] The most popular sport in Australia is cricket, the most popular sport among Australian women is netball, while Australian rules football is the most popular sport in terms of spectatorship and television ratings.[164][165][166] Australia has hosted two Summer Olympic Games: Melbourne 1956 and Sydney 2000. Australia has also hosted five editions of the Commonwealth Games (Sydney 1938, Perth 1962, Brisbane 1982, Melbourne 2006, and Gold Coast 2018). In 2006 Australia joined the Asian Football Confederation and qualified for the 2010 and 2014 World Cups as an Asian entrant.[167]

Notes

- ↑ Most recent estimated population of Australia , Papua New Guinea (excluding the Islands Region), and Indonesia's Aru Islands Regency and Western New Guinea.

- ↑ Excluding Christmas Island, the Cocos (Keeling) Islands, Heard Island and McDonald Islands, the Lord Howe Island Group (New South Wales), Macquarie Island (Tasmania), and Norfolk Island.

- ↑ Excluding the Islands Region.

- ↑ Excluding Cato Reef, Elizabeth Reef, Mellish Reef, Middleton Reef, and some small reefs on the Cato Trough.

See also

- Australian Plate

- List of islands in the Pacific Ocean

- Outline of Australia

- Paleoclimatology

References

- ↑ New, T.R. (2002). "Neuroptera of Wallacea: a transitional fauna between major geographical regions". Acta Zoologica Academiae Scientiarum Hungaricae 48 (2): 217–27. http://actazool.nhmus.hu/48Suppl2/newwallace.pdf.

- ↑ Agency, Digital Transformation. "The Australian continent". https://info.australia.gov.au/about-australia/our-country/the-australian-continent.

- ↑ Löffler, Ernst; A.J. Rose, Anneliese Löffler & Denis Warner (1983). Australia:Portrait of a Continent. Richmond, Victoria: Hutchinson Group. p. 17. ISBN 978-0-09-130460-7.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Seetharaman, G. (13 August 2017). "Seven decades after Independence, many small languages in India face extinction threat". The Economic Times. http://economictimes.indiatimes.com/news/politics-and-nation/seven-decades-after-independence-many-small-languages-in-india-facing-extinction-threat/articleshow/60038323.cms.

- ↑ "World Bank data on urbanisation". World Development Indicators. World Bank. 2005. http://devdata.worldbank.org/wdi2005/Table3_10.htm.

- ↑ "BBC: First contact with isolated tribes?". Survival International. http://www.survivalinternational.org/news/2191.

- ↑ "Geographic Distribution of the Population". 24 May 2012. http://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/abs@.nsf/Lookup/by Subject/1301.0~2012~Main Features~Geographic distribution of the population~49.

- ↑ Data refer mostly to the year 2014. World Economic Outlook Database-April 2015, International Monetary Fund. Accessed on 25 April 2015.

- ↑ "Australia: World Audit Democracy Profile". WorldAudit.org. http://www.worldaudit.org/countries/australia.htm.

- ↑ Statistics, c=AU; o=Commonwealth of Australia; ou=Australian Bureau of (19 May 2023). "Main Features – Cultural Diversity Article". http://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/abs@.nsf/Lookup/by+Subject/2071.0~2016~Main+Features~Cultural+Diversity+Article~20?OpenDocument&ref=story.

- ↑ United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division, (2019). 'International Migration' in International migrant stock 2019. Accessed from International migrant stock 2015: maps on 24 May 2017.

- ↑ "What Did Australia Look Like When the First People Arrived?". https://www.thoughtco.com/sahul-pleistocene-continent-172704.

- ↑ Carmack, R.M. (2013). Anthropology and Global History: From Tribes to the Modern World-System. AltaMira Press. p. 33. ISBN 978-0-7591-2390-8. https://books.google.com/books?id=lQR1AQAAQBAJ&pg=PA33. Retrieved 6 August 2020.

- ↑ Cochrane, Ethan E.; Hunt, Terry L. (8 August 2018). The Oxford Handbook of Prehistoric Oceania. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780199925070. https://books.google.com/books?id=JZRODwAAQBAJ&q=prehistoric+continent+sahul&pg=PA35.

- ↑ O'Connor, S.; Veth, P.M.; Spriggs, M. (2007). The Archaeology of the Aru Islands, Eastern Indonesia. Terra Australis. ANU e Press. p. 10. ISBN 978-1-921313-04-2. https://books.google.com/books?id=KSkIKYztV_AC&pg=PA10. Retrieved 6 August 2020.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 Lewis & Wigen, The Myth of Continents (1997), p. 32: "...the 1950s... was also the period when... Oceania as a "great division" was replaced by Australia as a continent along with a series of isolated and continentally attached islands. [Footnote 78: When Southeast Asia was conceptualised as a world region during World War II..., Indonesia and the Philippines were perforce added to Asia, which reduced the extent of Oceania, leading to a reconceptualisation of Australia as a continent in its own right. This manoeuvre is apparent in postwar atlases]"

- ↑ Southwell, Thomas (1889). Transactions of the Norfolk and Norwich Naturalists' Society: Volume 4. Norfolk Naturalists' Trust and Norfolk & Norwich Naturalists' Society.. https://books.google.com/books?id=P0NMAAAAYAAJ&dq="greenland"+"island+continent"&pg=PA164. Retrieved 16 November 2022.

- ↑ The Journal of the Royal Aeronautical Society: Volume 36. Royal Aeronautical Society. 1932. https://books.google.com/books?id=sJPyAAAAMAAJ&q="continent+of+greenland". Retrieved 16 November 2022.

- ↑ Bartholomew, John (1873). Zell's Descriptive Hand Atlas of the World. T.E. Zell. p. 7. https://books.google.com/books?id=gmSp46xxpJQC&dq="oceania"+"yokohama"+"australia"&pg=PA3. Retrieved 20 August 2022.

- ↑ Goodrich, Samuel Griswold (1854). History of All Nations. Miller, Orton and Mulligan. https://books.google.com/books?id=heJPYUnr70kC&dq="aleutian+islands"+"oceania"&pg=PA52. Retrieved 20 December 2022.

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 21.2 Wallace, Alfred Russel (1879). Australasia. The University of Michigan. p. 2. https://books.google.com/books?id=e2kcAAAAMAAJ&dq="oceania+is+the+word+often"&pg=PA2. Retrieved 12 March 2022. "Oceania is the word often used by continental geographers to describe the great world of islands we are now entering upon [...] This boundless watery domain, which extends northwards of Behring Straits and southward to the Antarctic barrier of ice, is studded with many island groups, which are, however, very irregularly distributed over its surface. The more northerly section, lying between Japan and California and between the Aleutian and Hawaiian Archipelagos is relived by nothing but a few solitary reefs and rocks at enormously distant intervals."

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 Cornell, Sophia S. (1857). Cornell's Primary Geography: Forming Part First of a Systematic Series of School Geographies. Harvard University. https://books.google.com/books?id=1Z9hizT9tiAC&dq="included+in+oceania"&pg=RA2-PA95. Retrieved 31 March 2022.

- ↑ Hillstrom, Kevin; Hillstrom, Laurie Collier (2003). Australia, Oceania, and Antarctica: A Continental Overview of Environmental Issues. 3. ABC-CLIO. p. 25. ISBN 9781576076941. "...defined here as the continent nation of Australia, New Zealand, and twenty-two other island countries and territories sprinkled over more than 40 million square kilometres of the South Pacific."

- ↑ Lyons, Paul (2006). American Pacificism: Oceania in the U.S. Imagination. p. 30. https://archive.org/details/americanpacifici00lyon.

- ↑ "Countries or areas / geographical regions". United Nations. https://unstats.un.org/unsd/methodology/m49/.

- ↑ Status of the 1950 Census Program in the United States: A Preliminary Report. United States. Bureau of the Census. 1951. https://books.google.com/books?id=h3v502REqhUC&dq=United+Nations+"oceania"&pg=PA58. Retrieved 24 November 2022.

- ↑ Westaway, J.; Quintao, V.; de Jesus Marcal, S. (2018). "Preliminary checklist of the naturalised and pest plants of Timor-Leste". Blumea 63 (2): 157–166. doi:10.3767/blumea.2018.63.02.13.

- ↑ Lewis, Martin W.; Kären E. Wigen (1997). The Myth of Continents: a Critique of Metageography. Berkeley: University of California Press. p. 32. ISBN 978-0-520-20742-4. https://archive.org/details/mythcontinentscr00lewi. "Interestingly enough, the answer [from a scholar who sought to calculate the number of continents] conformed almost precisely to the conventional list: North America, South America, Europe, Asia, Oceania (Australia plus New Zealand), Africa, and Antarctica."

- ↑ "Australia and Oceania - the World Factbook". https://www.cia.gov/the-world-factbook/australia-and-oceania/.

- ↑ "Divisões dos continentes". IBGE. https://atlasescolar.ibge.gov.br/images/atlas/mapas_mundo/mundo_034_divisao_continentes.pdf.

- ↑ Mears, Eliot Grinnell (1945). Pacific Ocean Handbook. J. L. Delkin. pp. 45. https://books.google.com/books?id=ku04AAAAIAAJ&q="customary"+"exclude"+"north+pacific"+"aleutians". Retrieved 27 July 2022.

- ↑ Cust, Robert Needham (1887). Linguistic and Oriental Essays: 1847-1887. Trübner & Company. p. 518. https://books.google.com/books?id=vZ4KtNU2-PMC. Retrieved 27 March 2022.

- ↑ 33.0 33.1 Ballard, Chris (1993). "Stimulating minds to fantasy? A critical etymology for Sahul". Canberra: Australian National University. pp. 19–20. ISBN 0-7315-1540-4.

- ↑ Allen, J. (1977). Sunda and Sahul: Prehistorical studies in Southeast Asia, Melanesia and Australia. London: Academic Press. ISBN 978-0-12-051250-8. https://archive.org/details/sundasahulprehis0000unse.

- ↑ Filewood, W. (1984). "The Torres connection: Zoogeography of New Guinea". Carlisle, W.A.: Hesperian Press. pp. 1124–1125. ISBN 0-85905-036-X.

- ↑ e.g. Flannery, Timothy Fridtjof (1994). The future eaters: An ecological history of the Australasian lands and people. Chatswood, NSW: Reed. pp. 42, 67. ISBN 978-0-7301-0422-3. https://archive.org/details/isbn_0730104877/page/42.

- ↑ Theroux, Paul (1992). The happy isles of Oceania: Paddling the Pacific. London: Penguin. ISBN 978-0-14-015976-9.

- ↑ Wareham, Evelyn (September 2002). "From Explorers to Evangelists: Archivists, Recordkeeping, and Remembering in the Pacific Islands". Archival Science 2 (3–4): 187–207. doi:10.1007/BF02435621.

- ↑ Dawkins, Richard (2004). The ancestor's tale: A pilgrimage to the dawn of evolution. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. p. 224. ISBN 978-0-618-00583-3.

- ↑ e.g. O'Connell, James F.; Allen, Jim (2007). "Pre-LGM Sahul (Pleistocene Australia-New Guinea) and the Archaeology of Early Modern Humans". in Mellars, P.; Boyle, K.; Bar-Yosef, O. et al.. Rethinking the Human Revolution. Cambridge: McDonald Institute for Archaeological Research. pp. 395–410. http://www.anthro.utah.edu/PDFs/joc/32o_conn.pdf. Retrieved 26 February 2008.

- ↑ Pain, C.F., Villans, B.J., Roach, I.C., Worrall, L. & Wilford, J.R. (2012): Old, flat and red – Australia's distinctive landscape. In: Shaping a Nation: A Geology of Australia. Blewitt, R.S. (Ed.) Geoscience Australia and ANU E Press, Canberra. Pp. 227–275 ISBN 978-1-922103-43-7

- ↑ Keith Lewis; Scott D. Nodder and Lionel Carter (11 January 2007). "Zealandia: the New Zealand continent". The Encyclopedia of New Zealand. http://www.teara.govt.nz/EarthSeaAndSky/OceanStudyAndConservation/SeaFloorGeology/1/en. Retrieved 22 February 2007.

- ↑ Norman, Kasih (2 April 2018). "Island-hopping study shows the most likely route the first people took to Australia". https://phys.org/news/2018-04-island-hopping-route-people-australia.html.

- ↑ Johnson, David Peter (2004). The Geology of Australia. Port Melbourne, Victoria: Cambridge University Press. p. 12.

- ↑ "Big Bank Shoals of the Timor Sea: An environmental resource atlas". Australian Institute of Marine Science. 2001. http://www.aims.gov.au/pages/reflib/bigbank/pages/bb-04.html.

- ↑ Wirantaprawira, Dr Willy (2003). "Republik Indonesia". Dr Willy Wirantaprawira. http://www.wirantaprawira.net/indon/land.html.

- ↑ Kevin Mccue (26 February 2010). "Land of earthquakes and volcanoes?". Australian Geographic. http://www.australiangeographic.com.au/journal/land-of-earthquakes-and-volcanoes.htm.

- ↑ Barrett; Dent (1996). Australian Environments: Place, Pattern and Process. Macmillan Education AU. p. 4. ISBN 978-0732931209. https://books.google.com/books?id=9AUcU_35C9sC. Retrieved 13 June 2014.

- ↑ Audley-Charles, M. G. (1986). "Timor–Tanimbar Trough: the foreland basin of the evolving Banda orogen". Spec. Publs Int. Ass. Sediment 8: 91–102. doi:10.1002/9781444303810.ch5. ISBN 9781444303810.

- ↑ "Statistical Yearbook of Croatia, 2007". http://www.dzs.hr/Hrv_Eng/ljetopis/2007/51-bind.pdf.

- ↑ Mascie-Taylor, D.B.A.C.G.N.; Mascie-Taylor, C.G.N.; Lasker, G.W. (1988). Biological Aspects of Human Migration. Cambridge University Press. p. 18. ISBN 9780521331098. https://books.google.com/books?id=eJD5XJlviukC&pg=PA18. Retrieved 9 August 2018.

- ↑ Michael Bird (Jun 2019). "Early human settlement of Sahul was not an accident". Scientific Reports 9 (1): 8220. doi:10.1038/s41598-019-42946-9. PMID 31209234. Bibcode: 2019NatSR...9.8220B.

- ↑ Michael Westaway (Jul 2019). "The first hominin fleet". Nature Ecology and Evolution 3 (7): 999–1000. doi:10.1038/s41559-019-0928-9. PMID 31209288. https://www.nature.com/articles/s41559-019-0928-9.epdf?referrer_access_token=PA76dahms_1XTJnjn6lbctRgN0jAjWel9jnR3ZoTv0OhaZU2rDQxxnW7pRhHxUzdPKFDe4x2pNM8UMQJJH2Mmu04w_2fphtd8kAmaX4EWbxv1eB8QfUyM8s7QqsqEBEAAkBrCIL-v8ANceCTpbSZJWBnNHe1rfQLsrykKpD3u6wqjZGzVIhbqWS6IKYUFmMkYSmJVVxw5KE2JPGJwuTlOYFXsj4UAifN0IbGvgVCV_QFzpeyKrr1FP5Eehm_EuBg738XZpIvnpSy3Nhbs-QyvJdnyGHw3Fv-dcjUbhAoXjKXTZmXIM9lWk1ADc9ZzIQK&tracking_referrer=www.newscientist.com.

- ↑ Graham Lawton (25 January 2020). "The epic ocean journey that took Stone Age people to Australia". New Scientist. https://www.newscientist.com/article/mg24532660-600-the-epic-ocean-journey-that-took-stone-age-people-to-australia/.

- ↑ Rasmussen, Morten et al. (7 October 2011). "An Aboriginal Australian Genome Reveals Separate Human Dispersals into Asia". Science 334 (6052): 94–98. doi:10.1126/science.1211177. PMID 21940856. Bibcode: 2011Sci...334...94R.

- ↑ Illumina (April 2012). "Sequencing Uncovers a 9,000 Mile Walkabout". http://www.illumina.com/documents/icommunity/article_2012_04_Aboriginal_Genome.pdf.

- ↑ Griffiths, Billy (26 February 2018). Deep Time Dreaming: Uncovering Ancient Australia. Black Inc.. ISBN 9781760640446.

- ↑ Jared Diamond. (1997). Guns, Germs, and Steel. Random House. London. pp 314–316

- ↑ Bowler J.M.; Johnston H.; Olley J.M.; Prescott J.R.; Roberts R.G.; Shawcross W.; Spooner N.A. (2003). "New ages for human occupation and climatic change at Lake Mungo, Australia.". Nature 421 (6925): 837–40. doi:10.1038/nature01383. PMID 12594511. Bibcode: 2003Natur.421..837B.

- ↑ Bowler, J. M. (1971). "Pleistocene salinities and climatic change: Evidence from lakes and lunettes in southeastern Australia". in Mulvaney, D. J.; Golson, J.. Aboriginal Man and Environment in Australia. Canberra: Australian National University Press. pp. 47–65. ISBN 0-7081-0452-5.

- ↑ "The Indigenous Collection". The Ian Potter Centre: NGV Australia. National Gallery of Victoria. http://www.ngv.vic.gov.au/whats-on/exhibitions/exhibitions/the-indigenous-collection.

- ↑ Gillespie, Richard (2002). "Dating the First Australians". Radiocarbon 44 (2): 455–72. doi:10.1017/S0033822200031830. Bibcode: 2002Radcb..44..455G. http://www-personal.une.edu.au/~pbrown3/Gillespie02.pdf. Retrieved 24 May 2010.

- ↑ Singh, Bilveer (2008). Papua: Geopolitics and the Quest for Nationhood. Transaction Publishers. p. 15.

- ↑ "Majapahit Overseas Empire, Digital Atlas of Indonesian History". http://www.indonesianhistory.info/map/majapahit.html.

- ↑ "Early humans lived in PNG highlands 50,000 years ago". Reuters. 30 September 2010. https://www.reuters.com/article/us-australia-png-humans-idUSTRE68T4X620100930.

- ↑ Albert-Marie-Ferdinand Anthiaume, "Un pilote et cartographe havrais au XVIe siècle: Guillaume Le Testu", Bulletin de Géographie Historique et Descriptive, Paris, Nos 1–2, 1911, pp. 135–202, n.b. p. 176.

- ↑ "The Internet Classics Archive | Meteorology by Aristotle". http://classics.mit.edu/Aristotle/meteorology.2.ii.html.

- ↑ Macrobius, Ambrosius Aurelius Theodosius (1000) (in latin). Zonenkarte. doi:10.7891/e-manuscripta-16478.

- ↑ John Noble Wilford: The Mapmakers, the Story of the Great Pioneers in Cartography from Antiquity to Space Age, p. 139, Vintage Books, Random House 1982, ISBN 0-394-75303-8

- ↑ Zuber, Mike A. (2011). "The Armchair Discovery of the Unknown Southern Continent: Gerardus Mercator, Philosophical Pretensions and a Competitive Trade". Early Science and Medicine 16 (6): 505–541. doi:10.1163/157338211X607772. https://www.academia.edu/1910165.

- ↑ Carlos Pedro Vairo, TERRA AUSTRALIS Historical Charts of Patagonia, Tierra del Fuego and Antarctica. Ed. Zagier & Urruty Publicationa, 2010.

- ↑ Spieghel der Australische Navigatie; cited by A. Lodewyckx, "The Name of Australia: Its Origin and Early Use", The Victorian Historical Magazine, Vol. XIII, No. 3, June 1929, pp. 100–191.

- ↑ J.P. Sigmond and L.H. Zuiderbaan (1979) Dutch Discoveries of Australia.Rigby Ltd, Australia. pp. 19–30 ISBN 0-7270-0800-5

- ↑ Primary Australian History: Book F [B6 Ages 10–11]. R.I.C. Publications. 2008. p. 6. ISBN 978-1-74126-688-7. https://books.google.com/books?id=_i98Pu5dDhkC&pg=PA6. Retrieved 12 June 2013.

- ↑ "European discovery of New Zealand". Encyclopedia of New Zealand. 4 March 2009. http://www.teara.govt.nz/en/european-discovery-of-new-zealand/2.

- ↑ "Cook's Journal: Daily Entries, 22 April 1770". http://southseas.nla.gov.au/journals/cook/17700422.html.

- ↑ "Cook's Journal 29 April 1770". http://southseas.nla.gov.au/journals/cook/17700429.html.

- ↑ "Once were warriors – smh.com.au". The Sydney Morning Herald. 11 November 2002. https://www.smh.com.au/articles/2002/11/10/1036308574533.html.

- ↑ "Sydney's history". City of Sydney. 2013. http://www.cityofsydney.nsw.gov.au/learn/sydneys-history.

- ↑ "Early European settlement". Parliament of New South Wales. 2014. http://www.parliament.nsw.gov.au/prod/web/common.nsf/key/HistoryEarlyEuropeanSettlement.

- ↑ John Waiko. Short History of Papua New Guinea (1993)

- ↑ "Papua New Guinea". State.gov. 8 October 2010. https://2009-2017.state.gov/r/pa/ei/bgn/2797.htm.

- ↑ "Bombing of Darwin: 70 years on – ABC News (Australian Broadcasting Corporation)". Abc.net.au. 17 February 2012. http://www.abc.net.au/news/2012-02-17/bombing-of-darwin-anniversary-special-coverage/3834410.

- ↑ "Wartime Issue 23 – New Guinea Offensive | Australian War Memorial". Awm.gov.au. http://www.awm.gov.au/wartime/23/new-guinea-offensive/.

- ↑ U.S. Dept. of Defence; International Crisis Group; and International Crisis Group . Archived 19 August 2014.

- ↑ "Thirty Years On". The Economist. 25 August 2005. https://www.economist.com/asia/2005/08/25/thirty-years-on.

- ↑ cited in Michael Dugan and Josef Swarc (1984) p. 139

- ↑ "DFAT.gov.au". DFAT.gov.au. 19 April 1984. http://www.dfat.gov.au/aib/overview.html.

- ↑ "Australia Burning: Fire Ecology, Policy and Management Issues". CSIRO Publishing. http://www.publish.csiro.au/samples/australiaburningsample.pdf.

- ↑ Korf, R. P. (1983). "Cyttaria (Cyttariales): coevolution with Nothofagus, and evolutionary relationship to the Boedijnpezizeae (Pezizales, Sarcoscyphaceae)". in Pirozynski, K. A.; Walker, J.. Pacific Mycogeography: a Preliminary Approach. Australian Journal of Botany Supplementary Series. 10. pp. 77–87. ISBN 0-643-03548-6.

- ↑ Newman, Arnold (2002). Tropical Rainforest: Our Most Valuable and Endangered Habitat With a Blueprint for Its Survival into the Third Millennium (2 ed.). Checkmark. ISBN 978-0816039739. https://archive.org/details/tropicalrainfore00newm_0.

- ↑ WWF: Bird wonders of New Guinea's western-most province, retrieved 11 May 2010

- ↑ Williams, J. et al. 2001. Biodiversity, Australia State of the Environment Report 2001 (Theme Report), CSIRO Publishing on behalf of the Department of the Environment and Heritage, Canberra. ISBN 0-643-06749-3

- ↑ Egerton, p. 122.

- ↑ Chapman, A.D. (2009). Numbers of Living Species in Australia and the World (2nd ed.). Australian Biological Resources Study. p. 14. ISBN 9780642568618. http://www.environment.gov.au/system/files/pages/2ee3f4a1-f130-465b-9c7a-79373680a067/files/nlsaw-2nd-complete.pdf.

- ↑ Egerton, L. ed. 2005. Encyclopedia of Australian wildlife. Reader's Digest

- ↑ "Australia's National Symbols". Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade. http://dfat.gov.au/about-australia/land-its-people/Pages/australias-national-symbols.aspx.

- ↑ "Welcome". Save the Tasmanian Devil: p. 1. June 2008. http://www.tassiedevil.com.au/tasdevil.nsf/downloads/D595436FECB69A66CA2576ED0083D3F6/$file/DevilNews_June_2008.pdf.

- ↑ Underhill D (1993) Australia's Dangerous Creatures, Reader's Digest, Sydney, New South Wales, ISBN 0-86438-018-6

- ↑ Low, T. (2014), Where Song Began: Australia's Birds and How They Changed the World, Tyre: Penguin Australia

- ↑ Centre, National Climate. "BOM – Climate of Australia". http://www.bom.gov.au/lam/climate/levelthree/ausclim/ausclim.html.

- ↑ Precipitation in Australia. Routledge. 1997. p. 376. ISBN 978-0-415-12519-2. https://books.google.com/books?id=uwQ7FulHCCsC&pg=PA376.

- ↑ Christianity in its Global Context, 1970–2020 Society, Religion, and Mission, Center for the Study of Global Christianity

- ↑ "Cultural diversity in Australia". 2071.0 – Reflecting a Nation: Stories from the 2011 Census, 2012–2013. Australian Bureau of Statistics. 21 June 2012. http://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/abs@.nsf/Latestproducts/2071.0Main Features902012–2013.

- ↑ "US Department of State International Religious Freedom Report 2003". https://2001-2009.state.gov/g/drl/rls/irf/2003/24317.htm.

- ↑ Silva, Diego B. (2019). "Language policy in Oceania". Alfa 63: 317–347. doi:10.1590/1981-5794-1909-4.

- ↑ Statistics, c=AU; o=Commonwealth of Australia; ou=Australian Bureau of (21 June 2012). "Main Features – Cultural Diversity in Australia". http://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/abs@.nsf/Lookup/2071.0main+features902012-2013.

- ↑ A.V. (24 July 2017). "Papua New Guinea's incredible linguistic diversity". The Economist. https://www.economist.com/blogs/economist-explains/2017/07/economist-explains-14.

- ↑ Papua New Guinea, Ethnologue

- ↑ Statistics, c=AU; o=Commonwealth of Australia; ou=Australian Bureau of. "Main Features – Net Overseas Migration". http://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/abs@.nsf/Latestproducts/3412.0Main+Features52015-16?opendocument&tabname=Summary&prodno=3412.0&issue=2015-16&num=&view=.

- ↑ "Sydney's melting pot of language". The Sydney Morning Herald. 2014. https://www.smh.com.au/data-point/sydney-languages.

- ↑ "Census 2016: Migrants make a cosmopolitan country". The Australian. 15 July 2017. http://www.theaustralian.com.au/news/inquirer/census-2016-migrants-make-a-cosmopolitan-country/news-story/da01bec138fc8600ea7bb84d1844ea80.

- ↑ "Population, dwellings, and ethnicity". .id. 2014. http://profile.id.com.au/sydney/population.

- ↑ "Regional, rural and urban development - OECD". http://www.oecd.org/gov/regional-policy/50242959.pdf.

- ↑ "Vicnet Directory Indian Community". Vicnet. http://www.vicnet.net.au/community/ethnic/indian/.

- ↑ "Vicnet Directory Sri Lankan Community". Vicnet. http://www.vicnet.net.au/community/ethnic/srilankan/.

- ↑ "Vietnamese Community Directory". yarranet.net.au. http://www.yarranet.net.au/~acacia/vietcom.htm.

- ↑ "7BridgesWalk.com.au". Bridge History. http://www.7bridgeswalk.com.au/pages/bridge-history.php#sydharbourbridge.

- ↑ "Sydney Harbour Bridge". Australian Government. 14 August 2008. http://australia.gov.au/about-australia/australian-story/sydney-harbour-bridge.

- ↑ Field listing – GDP (official exchange rate), CIA World Factbook

- ↑ "2012 Report (PDF)". http://wfe.if5.com/ReportGen.aspx?year=2012&month=10¤cy=usd&type=pdf&idTable=0.

- ↑ "Statement on Monetary Policy (November 2013)". 8 November 2013. http://www.rba.gov.au/publications/smp/2013/nov/html/index.html.

- ↑ Australian Bureau of Statistics (14 December 2017). "Tourism Satellite Account 2014–15:Key Figures". http://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/abs@.nsf/mf/5249.0?OpenDocument.

- ↑ "Visitor Arrivals Data". Tourism Australia. 10 January 2019. http://www.tourism.australia.com/statistics/arrivals.aspx.

- ↑ "2014 Quality of Living Worldwide City Rankings – Mercer Survey". mercer.com. 19 February 2014. http://www.mercer.com/qualityoflivingpr#city-rankings.

- ↑ "2014 Quality of Living Index". Mercer. 2014. http://www.mercer.com.au/newsroom/mercer-2014-quality-of-living-index.html.

- ↑ "The World According to GaWC 2010". Globalization and World Cities (GaWC) Study Group and Network. Loughborough University. http://www.lboro.ac.uk/gawc/world2010t.html.

- ↑ "Global Power City Index 2010". Tokyo, Japan: Institute for Urban Strategies at The Mori Memorial Foundation. October 2010. http://www.mori-m-foundation.or.jp/english/research/project/6/pdf/GPCI2010_English.pdf.

- ↑ "Happy birthday Melbourne: 181 and still kicking!". https://www.sbs.com.au/language/english/happy-birthday-melbourne-181-and-still-kicking.

- ↑ The Global Financial Centres Index 14 (September 2013) . Y/Zen Group. p 15. Retrieved 4 December 2013.

- ↑ 2012 Global Cities Index and Emerging Cities Outlook . A.T. Kearney. p 2. Retrieved 29 December 2013.

- ↑ "The World Factbook". https://www.cia.gov/the-world-factbook/countries/papua-new-guinea/.

- ↑ "APECPNG2018.ORG". http://www.apecpng2018.org/.

- ↑ World Economic Outlook Database, October 2015, International Monetary Fund. Database updated on 6 October 2015. Accessed on 6 October 2015.

- ↑ Asian Development Outlook 2015: Financing Asia’s Future Growth. Asian Development Bank (March 2015)

- ↑ "Raising the profile of PNG in Australia". Australian Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade. 9 March 2012. http://ministers.dfat.gov.au/marles/speeches/2012/rm_sp_120309.html.

- ↑ "Melbourne, Australia: City of Literature ", Creative Cities Network, UNESCO, retrieved: 10 August 2011

- ↑ "How Australia's Parliament works". Australian Geographic. 11 August 2010. http://www.australiangeographic.com.au/topics/features/2010/08/how-australias-parliament-works.

- ↑ Davison, Hirst & Macintyre 1998, pp. 287–8

- ↑ "Governor-General's Role". Governor-General of Australia. http://www.gg.gov.au/governorgeneral/category.php?id=2.

- ↑ "Glossary of Election Terms". Australian Broadcasting Corporation. http://www.abc.net.au/elections/federal/2007/guide/glossary.htm#coalition.

- ↑ "State of the Parties". Australian Broadcasting Corporation. http://www.abc.net.au/elections/federal/2007/results/sop.htm.

- ↑ Fenna, Alan; Robbins, Jane; Summers, John (2013). Government Politics in Australia. London, United Kingdom: Pearson Higher Education AU. p. 139. ISBN 978-1-4860-0138-5.

- ↑ Bradford, Sarah (1997). Elizabeth: A Biography of Britain's Queen. Riverhead Books. ISBN 978-1-57322-600-4. https://archive.org/details/elizabethbiograp00brad_0.

- ↑ Jupp, pp. 796–802.

- ↑ Teo and White, pp. 118–20.

- ↑ 147.0 147.1 147.2 Teo, Hsu-Ming; White, Richard (2003). Cultural history in Australia. UNSW Press. ISBN 0-86840-589-2. OCLC 1120581500. http://worldcat.org/oclc/1120581500.

- ↑ Davison, Hirst & Macintyre 1998, pp. 98–9

- ↑ Teo and White, pp. 125–27.

- ↑ Davison, Graeme; Hirst, John; Macintyre, Stuart, eds (1 January 2001). The Oxford Companion to Australian History. doi:10.1093/acref/9780195515039.001.0001. ISBN 978-0-19-551503-9. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/acref/9780195515039.001.0001.

- ↑ 151.0 151.1 Teo and White, pp. 121–23.

- ↑ Jupp, pp. 808–12, 74–77.

- ↑ James., Jupp (2001). The Australian people : an encyclopedia of the nation, its people and their origins. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-80789-1. OCLC 760277445. http://worldcat.org/oclc/760277445.

- ↑ Australian Museum, A Short History of the Australian Museum, http://australianmuseum.net.au/A-short-history-of-the-Australian-Museum

- ↑ National Gallery of Victoria – Victorian Heritage Register

- ↑ Kaur, Jaskiran (2013). "Where to party in Australia on New Year's Eve". International Business Times. http://au.ibtimes.com/articles/531947/20131227/party-new-year-s-eve-australia-sydney.htm.

- ↑ "Papua New Guinea – culture". Datec Pty Ltd. http://www.datec.com.au/png/culture.htm.

- ↑ "Australian Indigenous art". Australian Culture and Recreation Portal. Australia Government. 21 December 2007. http://www.cultureandrecreation.gov.au/articles/indigenous/art/index.htm.

- ↑ "Kakadu: Rock art". parksaustralia.gov.au. https://parksaustralia.gov.au/kakadu/people/rock-art.html.

- ↑ "Uluru-Kata Tjuta: Rock art". parksaustralia.gov.au. https://parksaustralia.gov.au/uluru/people-place/rock-art.html.

- ↑ "Aboriginal Heritage walk: Ku-ring-gai Chase National Park". nationalparks.nsw.gov.au. http://www.nationalparks.nsw.gov.au/things-to-do/Walking-tracks/Aboriginal-Heritage-walk.

- ↑ Graves, Randin. "Yolngu are People 2: They're not Clip Art". https://yidakistory.com/blog/page/4/.

- ↑ "PNG vow to upset World Cup odds". Rugby League (BBC). 15 October 2008. http://news.bbc.co.uk/sport2/hi/rugby_league/7671217.stm. "But it would still be one of the biggest shocks in World Cup history if Papua New Guinea – the only country to have Rugby League as its national Sport – were to qualify for the last 4."

- ↑ Australia (Countries & Cultures), Tracey Boraas, Capstone Press (2002), Page 54 ISBN 0736810757

- ↑ Planet Sport, Kath Woodward, 2012 p. 85 ISBN 041568112X

- ↑ Australia (Cultures of the World), Vijeya Rajendra, Sundran Rajendra, 2002, p. 101 ISBN 0761414738

- ↑ "FIFA world cup 2010 – qualifying rounds and places available by confederation". Fifa.com. 3 April 2009. https://www.fifa.com/worldcup/tournament/index.html.

Bibliography

- Davison, Graeme; Hirst, John; Macintyre, Stuart (1998). The Oxford Companion to Australian History. Melbourne: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-553597-6.

- Lewis, Martin W.; Wigen, Kären E. (1997). The Myth of Continents: a Critique of Metageography. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-20743-1. https://books.google.com/books?id=C2as0sWxFBAC.

- Ebach, Malte C. (ed) (2021) Handbook of Australasian Biogeography CRC Press. Ist Edition ISBN 9780367658168

External links

[ ⚑ ] 26°S 141°E / 26°S 141°E

|

Categories: [Continents] [Oceania] [Asia-Pacific] [Pacific Ocean] [Indian Ocean]

↧ Download as ZWI file | Last modified: 01/20/2026 02:05:23 | 280 views

☰ Source: https://handwiki.org/wiki/Earth:Australia_(continent) | License: CC BY-SA 3.0

_(Tasmania)_-_(Frank_Hurley)_(9711313115).jpg)

KSF

KSF