Merovingian Dynasty

From Nwe

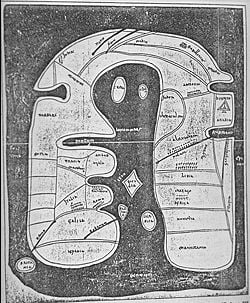

From Nwe The Merovingians were a dynasty of Frankish kings who ruled a frequently fluctuating area, largely corresponding to ancient Gaul, from the fifth to the eighth century. They were sometimes referred to as the "long-haired kings" (Latin reges criniti) by contemporaries, for their symbolically unshorn hair (traditionally the tribal leader of the Franks wore his hair long, while the warriors trimmed theirs short). The term is drawn directly from Germanic, akin to their dynasty's Old English name Merewīowing. Following the collapse of the Roman Empire, the Merovingian's helped to re-shape the map of Europe and to give stability to the region that would emerge as the country of France. The Merovingian grew weak as kings and were succeeded by the more ambitious Carolingian Dynasty that would itself evolve as the Holy Roman Empire. The Merovingians' interest in the world beyond their own borders is evidenced by the survival of their famous map. They helped to shape the European space. Popular culture depicts the Merovingians as descendants of Jesus Christ.

Origins

The Merovingian dynasty owes its name to Merovech or Merowig (sometimes Latinised as Meroveus or Merovius), leader of the Salian Franks from c. 447 to 457 C.E., and emerges into wider history with the victories of his son Childeric I (reigned c. 457 – 481) against the Visigoths, Saxons, and Alemanni. Childeric's son Clovis I went on to unite most of Gaul north of the Loire under his control around 486, when he defeated Syagrius, the Roman ruler in those parts. He won the Battle of Tolbiac against the Alemanni in 496, on which occasion he adopted his wife's Nicene Christian faith, and decisively defeated the Visigothic kingdom of Toulouse in the Battle of Vouillé in 507. After Clovis' death, his kingdom was partitioned among his four sons, according to Frankish custom. Over the next century, this tradition of partition would continue. Even when multiple Merovingian kings ruled, the kingdom—not unlike the late Roman Empire—was conceived of as a single entity ruled collectively by several kings (in their own realms) and the turn of events could result in the reunification of the whole kingdom under a single king. Leadership among the early Merovingians was based on mythical descent and alleged divine patronage, expressed in terms of continued military success.

Character

The Merovingian king was the master of the spoils of war, both movable and in lands and their folk, and he was in charge of the redistribution of conquered wealth among the first of his followers. "When he died his property was divided equally among his heirs as though it were private property: the kingdom was a form of patrimony" (Rouche 1987, 420). The kings appointed magnates to be comites, charging them with defense, administration, and the judgment of disputes. This happened against the backdrop of a newly isolated Europe without its Roman systems of taxation and bureaucracy, the Franks having taken over administration as they gradually penetrated into the thoroughly Romanised west and south of Gaul. The counts had to provide armies, enlisting their milites and endowing them with land in return. These armies were subject to the king's call for military support. There were annual national assemblies of the nobles of the realm and their armed retainers which decided major policies of warmaking. The army also acclaimed new kings by raising them on its shields in a continuance of ancient practice which made the king the leader of the warrior-band, not a head of state. Furthermore, the king was expected to support himself with the products of his private domain (royal demesne), which was called the fisc. Some scholars have attributed this to the Merovingians lacking a sense of res publica, but other historians have criticized this view as an oversimplification. This system developed in time into feudalism, and expectations of royal self-sufficiency lasted until the Hundred Years' War.

Trade declined with the decline and fall of the Roman Empire, and agricultural estates were mostly self-sufficient. The remaining international trade was dominated by Middle Eastern merchants.

Merovingian law was not universal law based on rational equity, generally applicable to all, as Roman law; it was applied to each man according to his origin: Ripuarian Franks were subject to their own Lex Ribuaria, codified at a late date (Beyerle and Buchner 1954), while the so-called Lex Salica (Salic Law) of the Salian clans, first tentatively codified in 511 (Rouche 1987, 423) was invoked under medieval exigencies as late as the Valois era. In this the Franks lagged behind the Burgundians and the Visigoths, that they had no universal Roman-based law. In Merovingian times, law remained in the rote memorization of rachimburgs, who memorized all the precedents on which it was based, for Merovingian law did not admit of the concept of creating new law, only of maintaining tradition. Nor did its Germanic traditions offer any code of civil law required of urbanized society, such as Justinian caused to be assembled and promulgated in the Byzantine Empire. The few surviving Merovingian edicts are almost entirely concerned with settling divisions of estates among heirs.

History

The Merovingian kingdom, which included, from at latest 509, all the Franks and all of Gaul but Burgundy, from its first division in 511 was in an almost constant state of war, usually civil. The sons of Clovis maintained their fraternal bonds in wars with the Burgundians, but showed that dangerous vice of personal aggrandizement when their brothers died. Heirs were seized and executed and kingdoms annexed. Eventually, fresh from his latest familial homicide, Clotaire I reunited, in 558, the entire Frankish realm under one ruler. He survived only three years and in turn his realm was divided into quarters for his four living sons.

The second division of the realm was not marked by the confraternal ventures of the first, for the eldest son was debauched and short-lived and the youngest an exemplar of all that was not admirable in the dynasty. Civil wars between the Neustrian and Austrasian factions which were developing did not cease until all the realms had fallen into Clotaire II's hands. Thus reunited, the kingdom was necessarily weaker. The nobles had made great gains and procured enormous concessions from the kings who were purchasing their support. Though the dynasty would continue for over a century and though it would produce strong, effective scions in the future, its first century, which established the Frankish state as the most stable and important in Western Europe, also dilapidated it beyond recovery. Its effective rule notably diminished, the increasingly token presence of the kings was required to legitimize any action by the mayors of the palaces who had risen during the final decades of war to a prominence which would become regal in the next century. During the remainder of the seventh century, the kings ceased to wield effective political power and became more and more symbolic figures; they began to allot more and more day-to-day administration to that powerful official in their household, the mayor.

After the reign of the powerful Dagobert I (died 639), who had spent much of his career invading foreign lands, such as Spain and the pagan Slavic territories to the east, the kings are known as rois fainéants ("do-nothing kings"). Though, in truth, no kings but the last two did nothing, their own will counted for little in the decision-making process. The dynasty had sapped itself of its vital energy and the kings mounted the throne at a young age and died in the prime of life, while the mayors warred with one another for the supremacy of their realm. The Austrasians under the Arnulfing Pepin the Middle eventually triumphed in 687 at the Battle of Tertry and the chroniclers state unapologetically that, in that year, began the rule of Pepin.

Among the strong-willed kings who ruled during these desolate times, Dagobert II and Chilperic II deserve mention, but the mayors continued to exert their authority in both Neustria and Austrasia. Pepin's son Charles Martel even for a few years ruled without a king, though he himself did not assume the royal dignity. Later, his son Pepin the Younger or Pepin the Short, gathered support among Frankish nobles for a change in dynasty. When Pope Zachary appealed to him for assistance against the Lombards, Pepin insisted that the church sanction his coronation in exchange. In 751, Childeric III, the last Merovingian royal, was deposed. He was allowed to live, but his long hair was cut and he was sent to a monastery.

Historiography and sources

There exists a limited number of contemporary sources for the history of the Merovingian Franks, but those which have survived cover the entire period from Clovis' succession to Childeric's deposition. First and foremost among chroniclers of the age is the canonised bishop of Tours, Gregory of Tours. His Decem Libri Historiarum is a primary source for the reigns of the sons of Clotaire II and their descendants until Gregory's own death.

The next major source, far less organized than Gregory's work, is the Chronicle of Fredegar, begun by Fredegar but continued by unknown authors. It covers the period from 584 to 641, though its continuators, under Carolingian patronage, extended it to 768, after the close of the Merovingian era. It is the only primary narrative source for much of its period. The only other major contemporary source is the Liber Historiae Francorum, which covers the final chapter of Merovingian history: its author(s) ends with a reference to Theuderic IV's sixth year, which would be 727. It was widely read, though it was undoubtedly a piece of Carolingian work.

Aside from these chronicles, the only surviving reservoires of historiography are letters, capitularies, and the like. Clerical men such as Gregory and Sulpitius the Pious were letter-writers, though relatively few letters survive. Edicts, grants, and judicial decisions survive, as well as the famous Lex Salica, mentioned above. From the reign of Clotaire II and Dagobert I survive many examples of the royal position as the supreme justice and final arbiter.

Finally, archaeological evidence cannot be ignored as a source for information, at the very least, on the modus vivendi of the Franks of the time. Among the greatest discoveries of lost objects was the 1653 accidental uncovering of Childeric I's tomb in the church of Saint Brice in Tournai. The grave objects included a golden bull's head and the famous golden insects (perhaps bees, cicadas, aphids, or flies) on which Napoleon modeled his coronation cloak. In 1957, the sepulchre of Clotaire I's second wife, Aregund, was discovered in Saint Denis Basilica in Paris. The funerary clothing and jewelry were reasonably well-preserved, giving us a look into the costume of the time.

Numismatics

Merovingian coins are on display at Monnaie de Paris, (the French mint) at 11, quai de Conti, Paris, France.

Merovingians in popular culture

- Michael Baigent, Richard Leigh, and Henry Lincoln use the Merovingians in their book, The Holy Blood and the Holy Grail (1982, reprinted 2004; NY: Delacorte Press, ISBN 0-385-33859-7, as Holy Blood, Holy Grail), which later influenced the novel The Da Vinci Code, by Dan Brown (NY: Anchor Books, 2003 ISBN 9781400079179). The claim was that the Merovingians were the descendants of Jesus Christ; it is seen as popular pseudohistory by academic historians.

- The Merovingian is a powerful computer program, portrayed by Lambert Wilson, in the 2003 science-fiction movies The Matrix Reloaded and The Matrix Revolutions. His character has chosen a French accent, clothing style, and attitude. He is a broker of power and knowledge.

References

ISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Ewig, Eugen. Die Merowinger und das Imperium. Opladen: Westdeutscher Verlag, 1983. ISBN 9783531072616

- Fouracre, Paul, and Richard A. Gerberding. Late Merovingian France: History and Hagiography, 640-720. Manchester medieval sources series. Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1996. ISBN 9780719047909

- Geary, Patrick J. Before France and Germany: The Creation and Transformation of the Merovingian World. Oxford & New York: Oxford University Press, 1998. ISBN 9780195044577

- Kaiser, Reinhold. Das römische Erbe und das Merowingerreich. (Enzyklopädie deutscher Geschichte 26) München: Oldenbourg, 1993. ISBN 9783486557831

- Moreira, Isabel. Dreams, Visions, and Spiritual Authority in Merovingian Gaul. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2000. ISBN 9780801436611

- Oman, Charles. Europe 476-918. London: Rivington, 1893.

- Rouche, Michael. "Private life conquers State and Society" in Paul Veyne (ed.), A History of Private Life: 1. From Pagan Rome to Byzantium. Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press, 1987. ISBN 9780674399754

- Wood, I.N. The Merovingian kingdoms, 450-751. NY: Longman, 1994. ISBN 9780582218789

External links

All links retrieved November 9, 2022.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.

↧ Download as ZWI file | Last modified: 02/04/2023 02:12:01 | 8 views

☰ Source: https://www.newworldencyclopedia.org/entry/Merovingian | License: CC BY-SA 3.0

ZWI signed:

ZWI signed:

KSF

KSF