Mutiny

From Nwe

From Nwe Mutiny is the act of conspiring to disobey an order that a group of similarly-situated individuals (typically members of the military; or the crew of any ship, even if they are civilians) are legally obliged to obey. The term is commonly used for a rebellion among members of the military against their superior officers. During the Age of Discovery, mutiny particularly meant open rebellion against a ship’s captain. This occurred, for example, during Magellan’s journey, resulting in the killing of one mutineer, the execution of another and the marooning of two others, and on Henry Hudson’s Discovery, resulting in Hudson and others being set adrift in a boat.

While there have been cases in which mutinous actions were justified, due to the leader acting in self-centered ways that endangered both the goal and the lives of the group, in many cases the self-centeredness was on the part of the mutineers, and thus mutiny was unjustified. As humankind develops, overcoming the nature of selfishness, and learns to live in harmony working for the benefit of the whole, mutiny becomes unnecessary.

Definitions

The Royal Navy’s Articles of War have changed slightly over the centuries they have been in force, but the 1757 version is representative—except that the death penalty no longer exists—and defines mutiny thus:

Article 19: If any person in or belonging to the fleet shall make or endeavor to make any mutinous assembly upon any pretence whatsoever, every person offending herein, and being convicted thereof by the sentence of the court martial, shall suffer death: and if any person in or belonging to the fleet shall utter any words of sedition or mutiny, he shall suffer death, or such other punishment as a court martial shall deem him to deserve: and if any officer, mariner, or soldier on or belonging to the fleet, shall behave himself with contempt to his superior officer, being in the execution of his office, he shall be punished according to the nature of his offence by the judgment of a court martial.

Article 20: If any person in the fleet shall conceal any traitorous or mutinous practice or design, being convicted thereof by the sentence of a court martial, he shall suffer death, or any other punishment as a court martial shall think fit; and if any person, in or belonging to the fleet, shall conceal any traitorous or mutinous words spoken by any, to the prejudice of His Majesty or government, or any words, practice, or design, tending to the hindrance of the service, and shall not forthwith reveal the same to the commanding officer, or being present at any mutiny or sedition, shall not use his utmost endeavours to suppress the same, he shall be punished as a court martial shall think he deserves.[1]

The United States’ Uniform Code of Military Justice, Art. 94; 10 U.S.C. § 894 (2004) defines mutiny thus:

- Art. 94. (§ 894.) Mutiny or Sedition.

- (a) Any person subject to this code (chapter) who—

- (1) with intent to usurp or override lawful military authority, refuses, in concern with any other person, to obey orders or otherwise do his duty or creates any violence or disturbance is guilty of mutiny;

- (2) with intent to cause the overthrow or destruction of lawful civil authority, creates, in concert with any other person, revolt, violence, or other disturbance against that authority is guilty of sedition;

- (3) fails to do his utmost to prevent and suppress a mutiny or sedition being committed in his presence, or fails to take all reasonable means to inform his superior commissioned officer or commanding officer of a mutiny or sedition which he knows or has reason to believe is taking place, is guilty of a failure to suppress or report a mutiny or sedition.

- (b) A person who is found guilty of attempted mutiny, mutiny, sedition, or failure to suppress or report a mutiny or sedition shall be punished by death or such other punishment as a court-martial may direct.[2]

Penalty

Most countries still punish mutiny with particularly harsh penalties, sometimes even the death penalty. Mutiny is typically thought of only in a shipboard context, but many countries’ laws make no such distinction, and there have been a significant number of notable mutinies on land.

United Kingdom

The military law of England in early times existed, like the forces to which it applied, in a period of war only. Troops were raised for a particular service, and were disbanded upon the cessation of hostilities. The crown, by prerogative, made laws known as Articles of War, for the government and discipline of the troops while thus embodied and serving. Except for the punishment of desertion, which was made a felony by statute in the reign of Henry VI, these ordinances or Articles of War remained almost the sole authority for the enforcement of discipline.

In 1689 the first Mutiny Act was passed, passing the responsibility to enforce discipline within the military to Parliament. The Mutiny Act, altered in 1803, and the Articles of War defined the nature and punishment of mutiny, until the latter were replaced by the Army Discipline and Regulation Act in 1879. This, in turn, was replaced by the Army Act in 1881.[3]

Section 21(5) of the 1998 Human Rights Act completely abolished the death penalty in the United Kingdom. Previously to this, the death penalty had already been abolished for murder, but it remained in force for certain military offenses, including mutiny, although these provisions had not been used for several decades.[4]

United States

United States military law requires obedience only to lawful orders. Disobedience to unlawful orders is the obligation of every member of the U.S. armed forces, a principle established by the Nuremberg trials and reaffirmed in the aftermath of the My Lai Massacre. However, a U.S. soldier who disobeys an order after deeming it unlawful will almost certainly be court-martialed to determine whether the disobedience was proper.

Famous mutinies

- Henry Hudson's Discovery, June 1611, after being trapped in the ice all winter while exploring the Hudson Bay in search of a Northwest Passage. The crew mutinied and set Hudson, his teenage son John, and seven crewmen loyal to Hudson adrift in a small open boat to die.

- Batavia was a ship of the Dutch East India Company (VOC), built in 1628 in Amsterdam, which was struck by mutiny and shipwrecked during her maiden voyage.

- Corkbush Field mutiny occurred on 1647 during the early stages of the Second English Civil War.

- HMS Hermione was a 32-gun fifth-rate frigate of the British Royal Navy, launched in 1782, notorious for the mutiny which took place aboard her.

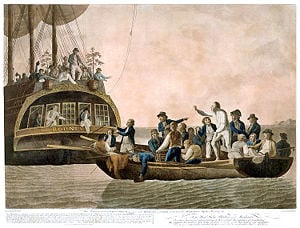

- Mutiny on the Bounty happened aboard a British Royal Navy ship in 1789. The story has been made famous by several books and films.

- The Spithead and Nore mutinies were two major mutinies by sailors of the British Royal Navy in 1797.

- The Indian rebellion of 1857 was a period of armed uprising in India against British colonial power, and was popularly remembered in Britain as the Sepoy Mutiny.

- The Russian battleship Potemkin was made famous by a rebellion of the crew against their oppressive officers in June of 1905 during the Russian Revolution of 1905.

- The Curragh Incident of July 20, 1914, occurred in the Curragh, Ireland, where British soldiers protested against enforcement of the Home Rule Act 1914.

- The failure of the Nivelle offensive in April and May 1917 resulted in widespread mutiny in many units of the French Army.

- The Wilhelmshaven mutiny broke out in the German High Seas Fleet on October 29, 1918. The mutiny ultimately led to the end of the First World War, to the collapse of the monarchy and to the establishment of the Weimar Republic.

- The Kronstadt rebellion was an unsuccessful uprising of Soviet sailors, led by Stepan Petrichenko, against the government of the early Russian SFSR in the first weeks of March in 1921. It proved to be the last major rebellion against Bolshevik rule.

- The Invergordon Mutiny was an industrial action by around a thousand sailors in the British Atlantic Fleet, that took place on September 15-16, 1931. For two days, ships of the Royal Navy at Invergordon were in open mutiny, in one of the few military strikes in British history.

- The Cocos Islands Mutiny was a failed mutiny by Sri Lankan servicemen on the then-British Cocos (Keeling) Islands during the Second World War.

- The Port Chicago mutiny on August 9, 1944, occurred three weeks after the Port Chicago disaster, in which 258 out of the 320 African-American sailors in the ordnance battalion refused to load any ammunition.

- The Royal Indian Navy Mutiny encompasses a total strike and subsequent mutiny by the Indian sailors of the Royal Indian Navy on board ship and shore establishments at Bombay (Mumbai) harbor on February 18, 1946.

- The SS Columbia Eagle incident occurred during the Vietnam War when sailors aboard an American merchant ship mutinied and hijacked the ship to Cambodia.

- There have been many incidents of resistance on the part of American soldiers serving in Iraq. In October 2004, members of the U.S. Army’s 343rd Quartermaster Company refused orders to deliver fuel from one base to another, along an extremely dangerous route, in vehicles with little to no armor. The soldiers argued that obeying orders would have resulted in heavy casualties. Furthermore, they alleged that the fuel in question was contaminated and useless.[5]

Reasons and relevance

While many mutinies were carried out in response to backpay and/or poor conditions within the military unit or on the ship, some mutinies, such as the Connaught Rangers mutiny and the Wilhelmshaven mutiny, were part of larger movements or revolutions.

In times and cultures where power "comes from the barrel of a gun," rather than through a constitutional mode of succession (such as hereditary monarchy or democratic elections), a major mutiny, especially in the capital, often leads to a change of ruler, sometimes even a new regime, and may therefore be induced by ambitious politicians hoping to replace the incumbent. In this fashion, many Roman emperors seized power at the head of a mutiny or were put on the throne after a successful one.

Mutinies are dealt with harshly because of the emphasis on discipline and obedience in most militaries. Soldiers are often punished by death for disobeying orders to set an example to others. The underlying fear is that soldiers will disobey orders in the heat of battle, thereby jeopardizing entire groups of troops. On board a ship at sea the safety of all depends upon the united efforts of the crew, and the captain is the agreed upon leader. Disobeying the captain's orders thus risks the life of all. Preventing this occurrence is considered paramount, justifying the harsh penalties.

Although committing a mutiny is seen as being on par with treason, mutinies can sometimes be justified. Soldiers are typically only obliged to execute orders within the scope of law. Soldiers ordered to commit crimes are entitled to disobey their superior officers. Examples of such orders would be the killing of unarmed opponents or civilians, or the use of rape as a weapon of war.

Notes

- ↑ The Articles of War – 1757. HMSRichmond.org. Retrieved April 14, 2007.

- ↑ Uniform Code of Military Justice. U.S. Army. Retrieved April 14, 2007.

- ↑ British Public Statutes Affected. Irish Statute Books. Retrieved April 14, 2007.

- ↑ Human Rights Act 1998 Office of Public Sector Information. Retrieved April 14, 2007.

- ↑ Orders Refused. AlterNet. Retrieved April 14, 2007.

References

ISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Bligh, William, Edward Christian, and R. D. Madison. 2001. The Bounty Mutiny. New York: Penguin Classics. ISBN 0140439161

- Guttridge, Leonard F. 1992. Mutiny: A History of Naval Insurrection. Annapolis, MD: United States Naval Institute Press. ISBN 0870212818

- Hibbert, Christopher. 1980. Great Mutiny: India 1857. New York: Penguin Books. ISBN 0140047522

- Woodman, Richard. 2005. A Brief History of Mutiny: A Brief History of Mutiny at Sea. New York: Carroll & Graf. ISBN 0786715677

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.

↧ Download as ZWI file | Last modified: 02/04/2023 02:26:11 | 19 views

☰ Source: https://www.newworldencyclopedia.org/entry/Mutiny | License: CC BY-SA 3.0

ZWI signed:

ZWI signed:

KSF

KSF