Simon Magus

From Nwe

From Nwe Simon Magus, also known as Simon the Sorcerer and Simon of Gitta, was a Samaritan gnostic who, according to ancient Christian accounts, allegedly asserted that he was an incarnation of God. In the various descriptions of his life, he was credited with all manner of arcane powers, including (most typically) the gift of flight. Though various early Christian writings such as the Acts of the Apostles mention him, there are no surviving writings from Simon Magus himself or from the members of his school. As such, it is difficult to judge the veracity of the charges laid against him.

Given its primarily derogatory meaning, "Simon Magus" and "Simonianism" also became generic terms used by ancient Christians as derogatory epithets for schismatics.

Christian Accounts

The figure of Simon appears prominently in the accounts of several early Christian authors, who regarded him as the first heretic. Indeed, these texts savagely denounced him, stating that he had the hubris to assert that his own divinity and to found a religious sect (Simonianism) based on that premise. As mentioned above, this means that virtually all of the surviving sources for the life and thought of Simon Magus are contained in the polemical treatises of the ancient Christian Orthodoxy, including the Acts of the Apostles, patristic works (such as the anti-heretical treatises written by Irenaeus, Justin Martyr, and Hippolytus), and the apocryphal Acts of Peter and Clementine literature.[1] [2] This being said, small fragments of a work written by him (or by one of his later followers using his name), the Apophasis Megalé ("Great Pronouncement") are still extant, and seem to reveal a fairly well-developed Gnostic metaphysics.[3] The patristic sources describe other Simonian treatises, including the The Four Quarters of the World and The Sermons of the Refuter, but these (and all other textual traces) are lost to us.[4] In spite of these tantalizingly unattestable fragments, it must be emphasized that the Simon who has been transmitted through history is primarily a legendary caricature of a heretic, rather than an actual individual.

The story of Simon Magus is perhaps most instructive to modern readers for the light that it sheds on the early Christian world view. More specifically, it must be noted that all depictions of the conjurer, from the Acts onward, accept the existence of his magical powers without question. As such, their issue is a moral one, addressing Simon's alleged claims of divinity and his use of magic to lead Christians from the "righteous path," rather than a factual objection to the assertions that he could levitate, animate the dead, and transform his physical body.[5] In this, it fits a common patristic paradigm, whereby the difference between magic (which is demonic) and miracles (which are angelic) is determined by the intentions of their respective practitioners: "Simon Magus used his magical powers to enhance his own status. He wanted to be revered as a God himself…. The apostles, on the other hand, used their powers only in recognition that they were simply vessels through which God's power flowed. It is in this latter form that magic acceptably enters Christian thought."[6] As a result, Simon must be comprehended as part of a historical context where all religious figures (including the apostles, martyrs, and saints) were understood to possess superhuman abilities, and that his sin was not the practicing of such arts but his hubris in practicing them for his own gain.

Acts of the Apostles

The earliest depiction of Simon Magus can be found in the canonical Book of Acts, where he is described as a convert of Saint Philip. In contravention his supposed conversion, he then proceeds to offend the Apostles by attempting to exchange material wealth for the miraculous ability of transmitting the Holy Spirit through the laying on of hands:

Now for some time a man named Simon had practiced sorcery in the city and amazed all the people of Samaria. He boasted that he was someone great, and all the people, both high and low, gave him their attention and exclaimed, "This man is the divine power known as the Great Power." They followed him because he had amazed them for a long time with his magic. But when they believed Philip as he preached the good news of the kingdom of God and the name of Jesus Christ, they were baptized, both men and women. Simon himself believed and was baptized. And he followed Philip everywhere, astonished by the great signs and miracles he saw.

When the apostles in Jerusalem heard that Samaria had accepted the word of God, they sent Peter and John to them. When they arrived, they prayed for them that they might receive the Holy Spirit, because the Holy Spirit had not yet come upon any of them; they had simply been baptized into the name of the Lord Jesus. Then Peter and John placed their hands on them, and they received the Holy Spirit.

When Simon saw that the Spirit was given at the laying on of the apostles' hands, he offered them money and said, "Give me also this ability so that everyone on whom I lay my hands may receive the Holy Spirit."

Peter answered: "May your money perish with you, because you thought you could buy the gift of God with money! You have no part or share in this ministry, because your heart is not right before God. Repent of this wickedness and pray to the Lord. Perhaps he will forgive you for having such a thought in your heart. For I see that you are full of bitterness and captive to sin."

Then Simon answered, "Pray to the Lord for me so that nothing you have said may happen to me" (Acts 8:9-24) (NIV).

The reviled sin of simony (paying for position and influence in the church, or, more broadly, "the buying or selling of sacred things") derives its name from that of the detested heretic.[7]

Acts of Peter

The apocryphal Acts of Peter (ca. 150-200 C.E.) provides a deeper and more nuanced portrait of alleged conflict between Simon and the early Church Fathers. Unlike the scanty mention of Simon in the Book of Acts, this text delves into his boastful claims of divinity, the founding of his schismatic sect, and the (obviously legendary) circumstances of his demise.

The first mention of the masterful wizard in the Acts of Peter concerns his appearance before an assembly of Christian converts and his success in luring away from the orthodox path through his magical abilities:

Now after a few days there was a great commotion in the midst of the church, for some said that they had seen wonderful works done by a certain man whose name was Simon, and that he was at Aricia, and they added further that he said he was a great power of God and without God he did nothing. Is not this the Christ? but we believe in him whom Paul preached unto us; for by him have we seen the dead raised, and men Delivered from divers infirmities: but this man seeketh contention, we know it (or, but what this contention is, we know not) for there is no small stir made among us. Perchance also he will now enter into Rome; for yesterday they besought him with great acclamations, saying unto him: Thou art God in Italy, thou art the saviour of the Romans: haste quickly unto Rome. But he spake to the people with a shrill voice, saying: Tomorrow about the seventh hour ye shall see me fly over the gate of the city in the form (habit) wherein ye now see me speaking unto you. Therefore, brethren, if it seem good unto you, let us go and await carefully the issue of the matter. They all therefore ran together and came unto the gate. And when it was the seventh hour, behold suddenly a dust was seen in the sky afar off, like a smoke shining with rays stretching far from it. And when he drew near to the gate, suddenly he was not seen: and thereafter he appeared, standing in the midst of the people; whom they all worshipped, and took knowledge that he was the same that was seen of them the day before.

And the brethren were not a little offended among themselves, seeing, moreover, that Paul was not at Rome, neither Timotheus nor Barnabas, for they had been sent into Macedonia by Paul, and that there was no man to comfort us, to speak nothing of them that had but just become catechumens. And as Simon exalted himself yet more by the works which he did, and many of them daily called Paul a sorcerer, and others a deceiver, of so great a multitude that had been stablished in the faith all fell away save Narcissus the presbyter and two women in the lodging of the Bithynians, and four that could no longer go out of their house, but were shut up (day and night): these gave themselves unto prayer (by day and night), beseeching the Lord that Paul might return quickly, or some other that should visit his servants, because the devil had made them fall by his wickedness [8].

When evaluating the text from within its own historical context, its xenophobic fear of heretical sects becomes more intelligible. Indeed, it was an era of dogmatic and ideological flux, where theological positions were less important than charismatic leadership. As such, the author's prayer "that Paul might return quickly" is an understandable request, as the community of the faithful, lacking the saint's forceful influence, were quick to impute Christ-like powers to a contending philosophical school.

In the text's account, the magus's malevolent influence upon the faithful eventually goaded Peter into responding with his own miracles—such as giving a dog a human voice, exorcising a demon, and imparting new life into a dried sardine. Unlike Simon, however, Peter's miracles were all executed in Christ's name:

- And Peter turned and saw a herring [sardine] hung in a window, and took it and said to the people: If ye now see this swimming in the water like a fish, will ye be able to believe in him whom I preach? And they said with one voice: Verily we will believe thee. Then he said -now there was a bath for swimming at hand: In thy name, O Jesu Christ, forasmuch as hitherto it is not believed in, in the sight of all these live and swim like a fish. And he cast the herring into the bath, and it lived and began to swim. And all the people saw the fish swimming, and it did not so at that hour only, lest it should be said that it was a delusion (phantasm), but he made it to swim for a long time, so that they brought much people from all quarters and showed them the herring that was made a living fish, so that certain of the people even cast bread to it; and they saw that it was whole. And seeing this, many followed Peter and believed in the Lord (Acts of Peter XII, translated by M.R. James).

Following Peter's exceptional demonstration of miraculous ability, Simon found it necessary to indulge in even greater prodigious feats in an attempt to win back Peter's converts (and to convince the disciple that his faith was ill-founded). This incremental, supernatural "arms race" proved to be the mage's undoing.

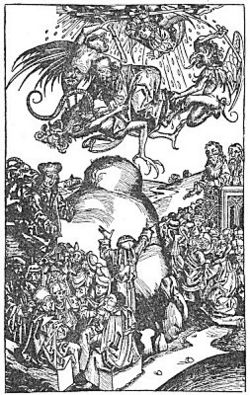

The final chapters of the Acts describe the disciple and the magus agreeing to engage in a mystical contest whose prize would be the faith of the assembled Roman citizens. Though Simon, using his gift of flight to his advantage, makes initial inroads, he is then trumped by Peter, who prays for him to fall:

- And already on the morrow a great multitude assembled at the Sacred Way to see him flying. And Peter came unto the place, having seen a vision (or, to see the sight), that he might convict him in this also; for when Simon entered into Rome, he amazed the multitudes by flying: but Peter that convicted him was then not yet living at Rome: which city he thus deceived by illusion, so that some were carried away by him (amazed at him).

- So then this man standing on an high place beheld Peter and began to say: Peter, at this time when I am going up before all this people that behold me, I say unto thee: If thy God is able, whom the Jews put to death, and stoned you that were chosen of him, let him show that faith in him is faith in God, and let it appear at this time, if it be worthy of God. For I, ascending up, will show myself unto all this multitude, who I am. And behold when he was lifted up on high, and all beheld him raised up above all Rome and the temples thereof and the mountains, the faithful looked toward Peter. And Peter seeing the strangeness of the sight cried unto the Lord Jesus Christ: If thou suffer this man to accomplish that which he hath set about, now will all they that have believed on thee be offended, and the signs and wonders which thou hast given them through me will not be believed: hasten thy grace, O Lord, and let him fall from the height and be disabled; and let him not die but be brought to nought, and break his leg in three places. And he fell from the height and brake his leg in three places. Then every man cast stones at him and went away home, and thenceforth believed Peter.(Acts of Peter XXXII, translated by M.R. James).

Some versions of the tale (which has been transmitted to the present in several iterations) claim that Saint Paul was also present during this spiritual contest. According to local folklore, the site of the Manichean conflict between the disciples and the heretic can still be identified by seeking a dented slab of marble in the courtyard, which is thought to have "melted" around the knees of the saints as they prayed for divine assistance. Also,, the Roman church of Santa Francesca Romana claims to have been built on the spot where Simon fell (a proposition that implies belief in this apocryphal legend).[9]

Given that the text has passed through several different recensions, there currently exist a range of opinions concerning the resolution of the confrontation between Peter and Simon. While most accounts suggest that the wizard ultimately perishes, at least three variant explanations for his death have been forwarded: 1) Simon fell to his death following Peter's prayer; 2) he survived the fall but was stoned to death by the enraged (and disillusioned) crowd below; or, 3) he survived the fall and escaped from the enraged townsfolk relatively unscathed, but died having his shattered legs operated on by an incompetent surgeon.[10]

Patristic Writings

Justin Martyr's Apology and Irenaeus's Adversus Haereses

Justin Martyr[11] and Irenaeus[12] recount the myth of Simon and Helene, which reportedly provided the metaphysical core of Simonian Gnosticism. According to this myth, God's first thought (his Ennoia (see Sophia)) was a female force that was responsible for the creation of the angels. Unfortunately, the angels rebelled against her out of jealousy, creating the physical world to be her prison and trapping her in the mortal body of a human female. Thereafter, she was entangled in an inescapable cycle of reincarnation (being rebord as Helen of Troy among many others), where each life saw her inexorably misused and shamed. This cycle culminated in the present, where she was finally reincarnated as Helene, a slave and prostitute in the Phoenician city of Tyre. Deciding to put an end to her suffering, God then descended (in the form of Simon Magus) to rescue his Ennoia. Once he redeemed Helene from slavery, the legendary wizard traveled about with her, proclaiming himself to be God and her to be the Ennoia, and promising that he would dissolve this unjust world the angels had made. This final claim provided both the eschatological and the soteriological underpinnings for Simonianism, as Simon decreed that those who trusted in him and Helene could return with them to the higher regions after his destruction of this realm.[13]

The other notable development in Justin and Irenaeus's heresiologies is the suggestion that the Simonians worshiped Simon in the form of Zeus and Helene in the form of Athena. As proof, they claim that a statue to Simon was erected by Claudius Caesar with the inscription Simoni Deo Sancto, "To Simon the Holy God." While a sculpture was indeed unearthed on the island in question, it was inscribed to Semo Sancus, a Sabine deity, leading many to believe that Justin Martyr confused Semoni Sancus with Simon.[14][15]

Origen's Contra Celsum

Origen's account, emerging several decade after that of Irenaeus, has certain one key difference with its predecessors: namely, it does not view Simon or Simonianism as threats. As such, it is comfortable discussing the limited number of adherents to these beliefs.

- There was also Simon the Samaritan magician, who wished to draw away certain by his magical arts. And on that occasion he was successful; but now-a-days it is impossible to find, I suppose, thirty of his followers in the entire world, and probably I have even overstated the number. There are exceedingly few in Palestine; while in the rest of the world, through which he desired to spread the glory of his name, you find it nowhere mentioned. And where it is found, it is found quoted from the Acts of the Apostles; so that it is to Christians that he owes this mention of himself, the unmistakable result having proved that Simon was in no respect divine.[16]

Hippolytus's Philosophumena

Hippolytus (in his Philosophumena) gives a much more doctrinally detailed account of Simonianism, which is said to include a metaphysical system of divine emanations. Given the doctrinal depth of this system, it seems likely that Hippolytus' report concerns a later, more developed form of Simonianism, and that the original doctrines of the group were simpler (as represented in the heresiologies of Justin Martyr and Irenaeus):

- When, therefore, Moses has spoken of “the six days in which God made heaven and earth, and rested on the seventh from all His works,” Simon, in a manner already specified, giving (these and other passages of Scripture) a different application (from the one intended by the holy writers), deifies himself. When, therefore, (the followers of Simon) affirm that there are three days begotten before sun and moon, they speak enigmatically of Mind and Intelligence, that is, Heaven and Earth, and of the seventh power, (I mean) the indefinite one. For these three powers are produced antecedent to all the rest. But when they say, “He begot me prior to all the Ages,” such statements, he says, are alleged to hold good concerning the seventh power. Now this seventh power, which was a power existing in the indefinite power, which was produced prior to all the Ages, this is, he says, the seventh power, respecting which Moses utters the following words: “And the Spirit of God was wafted over the water;” that is, says (the Simonian), the Spirit which contains all things in itself, and is an image of the indefinite power about which Simon speaks,—“an image from an incorruptible form, that alone reduces all things into order.” For this power that is wafted over the water, being begotten, he says, from an incorruptible form alone, reduces all things into order.[17]

Regardless, the Hippolytan account is most notable for its extensive quotations from the Apophasis Megale, as the Simonian text has only been transmitted to the present in an indirect or incomplete manner. As such, Hippolytus provides one of the most direct (if not necessarily unbiased) avenues to the comprehension of historical Simonianism.

Conflicting points of view

The different sources for information on Simon contain quite different pictures of him, so much so that it has been questioned whether they all refer to the same person. This issue is exemplified by the fact that the various accounts characterize and evaluate Simon quite differently, a fact that is cogently summarized by Mead:

- The student will at once perceive that though the Simon of the Acts and the Simon of the fathers both retain the two features of the possession of magical power and of collision with Peter, the tone of the narratives is entirely different. Though the apostles are naturally shown as rejecting with indignation the pecuniary offer of the thaumaturge, they display no hate for his personality, whereas the fathers depict him as the vilest of impostors and charlatans and hold him up to universal execration.[18]

Modern interpretation

According to some academics,[19] Simon Magus may be a cypher for Paul of Tarsus, as, according to them, Paul had originally been detested by the church. According to this theory, the heretic's name was overtly (and retroactively) altered when Paul was rehabilitated by virtue of his reputed authorship of the Pauline Epistles. Though this suggestion appears radical at first glance, Simon Magus is sometimes described in apocryphal legends in terms that could fit Paul. Furthermore, while the Christian Orthodoxy frequently portrayed Marcion as having been a follower of Simon Magus, Marcion's extant writings fail to even mention the existence of Simon. Instead, he overtly identifies himself as a follower of Paul. This argument receives support from the fact that various extra-canonical works from the time (such as the Clementine Texts and the Apocalypse of Stephen) also describe Paul in extremely negative terms, frequently depicting him as arch villain and enemy of Christianity. Though each of these facts is circumstantial, they do provide an intriguing case in support of an equation between Paul and Simon.

In general, Simon Magus is most significant to modern readers for the insights that his various (derogatory) biographies provide into the mindset and world-view of an early Christian—a perspective that conflated spiritual insight with miraculous power, and incompatible doctrines (i.e. Gnosticism) with heresy.

Notes

- ↑ Arland J. Hultgren and Steven A. Haggmark, (eds). The Earliest Christian Heretics: Readings from their Opponents. (Minneapolis, MN: Fortress Press, 1996), 15-27.

- ↑ Joyce E. Salisbury. The Blood of Martyrs: Unintended Consequences of Ancient Violence. (New York: Routledge, 2004), 56-58.

- ↑ G.R.S. Mead. Simon Magus: An Essay on the Founder of Simonianism Based on the Ancient Sources with a Re-evaluation of his Philosophy and Teachings. (Chicago: Ares, 1985), 49-91. Also online as Part III: The Theosophy of Simon. gnosis.org. Retrieved May 15, 2008.

- ↑ Mead, 46-47.

- ↑ Salisbury, 57.

- ↑ Salisbury, 57-58.

- ↑ "Simony" in the Online Etymology Dictionary. Retrieved August 24, 2007.

- ↑ Acts of Peter IV, translated by M.R. James. earlychristianwritings.com. Retrieved May 15, 2008.

- ↑ Salisbury, 57.

- ↑ Salisbury, 57 and compare with the conclusion of M. R. James's "The Acts of Peter" From The Apocryphal New Testament, Translation and Notes. (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1924) online translation (XXXII) earlychristianwritings.com. Retrieved May 15, 2008 , which exposits the botched surgery variant: "But Simon in his affliction found some to carry him by night on a bed from Rome unto Aricia; and he abode there a space, and was brought thence unto Terracina to one Castor that was banished from Rome upon an accusation of sorcery. And there he was sorely cut (Lat. by two physicians), and so Simon the angel of Satan came to his end."

- ↑ Justin discussed the heretic in his Apologies and in a lost work against heresies, the second of which Irenaeus likely used as his primary source (as per Mead, 39; F. J. Foakes Jackson. "Evidence for the Martyrdom of Peter and Paul in Rome." Journal of Biblical Literature 46 (1/2) (1927): 74-78, 75).

- ↑ Irenaeus's text, the Adversus Haereses ("On the Detection and Overthrow of the So-Called Gnosis")), was one of the most prevalent anti-heretical texts in the early church. For instance, "the Simon of Tertullian again is clearly taken from Irenæus, as the critics are agreed. 'Tertullian evidently knows no more than he read in Irenæus'" (Mead, 40). For this reason, the present overview does not bother to include Tertullian's account.

- ↑ See: Irenaeus, Against Heresies (XXIII) and Justin Martyr, ANTE-NICENE FATHERS, Volume 1: The Apostolic Fathers, Justin Martyr, Irenaeus, Edited by Alexander Roberts, D.D. and James Donaldson, First Apology (LVI). Both accessible online at the Christian Ethereal Classics Library. Note: the quotation from Justin is occasionally cited as i.26 (as per Mead, 8).

- ↑ Mead, 38-39;

- ↑ Chapter XXIII.—Doctrines and practices of Simon Magus and Menander. [1] 348 ff 2936. Christian Classics Ethereal Library. Retrieved May 15, 2008.

- ↑ Origen, Contra Celsum (LVII), Schaff 421-422. Accessible online at: Christian Classics Ethereal Library. While Origen's account does contain other details, the majority are simply repeated from the gospels and earlier patristics.

- ↑ Hippolytus, The Refutation of All Heresies, Schaff 77. Accessed online at the Christian Classics Ethereal Library.

- ↑ Mead, 38.

- ↑ See, for example, Mead (3, 42-43); Hermann Detering, "The Falsified Paul: Early Christianity in the Twilight." Journal of Higher Criticism (2003); Kohler and Krauss's article in the Jewish Encyclopedia.Retrieved May 15, 2008; and, Phil Harland's "Peter vs. Simon Magus (alias Paul) in the Pseudo-Clementines (NT Apocrypha 17)".Retrieved May 15, 2008.

References

ISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Cartlidge, David R. "The Fall and Rise of Simon Magus." Bible Review 21 (4) (Fall 2005): 24-36.

- Detering, Hermann. "The Falsified Paul: Early Christianity in the Twilight." Journal of Higher Criticism (2003).

- Ferreiro, Alberto. "Simon Magus and Priscillian in the Commonitorium of Vincent of Lérins." Vigiliae Christianae 49 (2) (May 1995): 180-188.

- Harland, Phil. Religions of the Ancient Mediterranean online [2]. Retrieved May 15, 2008.

- Hultgren, Arland J. and Steven A. Haggmark, (eds). The Earliest Christian Heretics: Readings from their Opponents. Minneapolis, MN: Fortress Press, 1996. ISBN 0800629639.

- Jackson, F. J. Foakes. "Evidence for the Martyrdom of Peter and Paul in Rome." Journal of Biblical Literature 46 (1/2) (1927): 74-78.

- James, M.R. "The Acts of Peter" From The Apocryphal New Testament, Translation and Notes. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1924.

- Laursen, John Christian, (ed). Histories of Heresy in Early Modern Europe: For, Against, and Beyond Persecution and Toleration. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2002. ISBN 0312294042.

- Legge, Francis. Forerunners and Rivals of Christianity, From 330 B.C.E. to 330 C.E. (1914), reprinted in two volumes bound as one, University Books New York, 1964.

- Mead, G. R. S. Simon Magus: An Essay on the Founder of Simonianism Based on the Ancient Sources with a Re-evaluation of his Philosophy and Teachings. Chicago: Ares, 1985. ISBN 0890052581. Also accessible online at The Gnosis Society Library.Retrieved May 15, 2008.

- Porter, J. R. The Lost Bible: Forgotten Scriptures Revealed. Chicago, Ill.: University of Chicago Press, 2001. ISBN 0226675793.

- Salisbury, Joyce E. The Blood of Martyrs: Unintended Consequences of Ancient Violence. New York: Routledge, 2004. ISBN 0415941296.

External links

All links retrieved January 29, 2023.

- Schaff's History of the Christian Church, volume II, chapter XI: THE HERESIES OF THE ANTE-NICENE AGE section 121: Simon Magus and the Simonians

- Jewish Encyclopedia: Simon Magus

- Catholic Encyclopedia: Simon Magus

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.

↧ Download as ZWI file | Last modified: 02/03/2023 22:54:41 | 52 views

☰ Source: https://www.newworldencyclopedia.org/entry/Simon_Magus | License: CC BY-SA 3.0

ZWI signed:

ZWI signed:

KSF

KSF