Fourth International

From Nwe

From Nwe | Part of the Politics series on Trotskyism |

Marxism Prominent Trotskyists Trotskyist groups Branches |

| Communism Portal

|

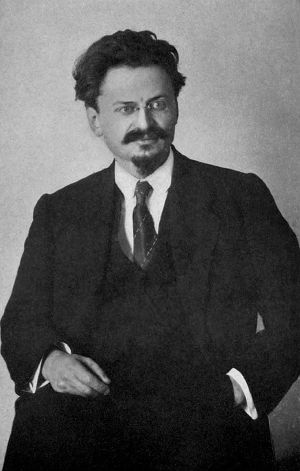

The Fourth International (FI) was a communist international organization working in opposition to both capitalism and Stalinism. Consisting of followers of Leon Trotsky, it strove for an eventual victory of the working class to bring about socialism.

In France in 1938, Trotsky and many of his supporters, having been expelled from the Soviet Union, considered the Comintern to have become lost to Stalinism and incapable of leading the international working class towards political power.[1] Thus, they founded their own competing "Fourth International." Throughout the better part of its existence, the Fourth International was hounded by agents of the Soviet secret police, opposed by capitalist countries such as France and the United States, and rejected by followers of the Soviet Union and later Maoism as illegitimate–a position these communists still hold today. When workers' uprisings occurred, they were usually under the influence of Soviet, Maoist, social democratic, or nationalist groups, leading to further defeats for Trotskyists.[2]

| Communism |

| Basic concepts |

| Marxist philosophy |

| Class struggle |

| Proletarian internationalism |

| Communist party |

| Ideologies |

| Marxism Leninism Maoism |

| Trotskyism Juche |

| Left Council |

| Religious Anarchist |

| Communist internationals |

| Communist League |

| First International |

| Comintern |

| Fourth International |

| Prominent communists |

| Karl Marx |

| Friedrich Engels |

| Rosa Luxemburg |

| Vladimir Lenin |

| Joseph Stalin |

| Leon Trotsky |

| Máo Zédōng |

| Related subjects |

| Anarchism |

| Anti-capitalism |

| Anti-communism |

| Communist state |

| Criticisms of communism |

| Democratic centralism |

| Dictatorship of the proletariat |

| History of communism |

| Left-wing politics |

| Luxemburgism |

| New Class New Left |

| Post-Communism |

| Eurocommunism |

| Titoism |

| Primitive communism |

| Socialism Stalinism |

| Socialist economics |

The FI suffered a split in 1940 and an even more significant split in 1953. Despite a partial reunification in 1963, more than one group claims to represent the political continuity of the Fourth International. The broad array of Trotskyist Internationals are split over which organization represents its political continuity.

Trotskyism

Trotskyists regard themselves as working in opposition to both capitalism and Stalinism as embodied by the leadership of the Soviet Union after Vladimir Lenin's death. Trotsky advocated proletarian revolution as set out in his theory of "permanent revolution," and believed that a workers' state would not be able to hold out against the pressures of a hostile capitalist world unless socialist revolutions quickly took hold in other countries as well. This theory was advanced in opposition to the view held by the Stalinists that "socialism in one country" could be built in the Soviet Union alone.[3] Furthermore, Trotsky and his supporters harshly criticized the increasingly totalitarian nature of Joseph Stalin's rule. They argued that socialism without democracy is impossible. Thus, faced with the increasing lack of democracy in the Soviet Union, they concluded that it was no longer a socialist workers' state, but a degenerated workers' state.[1]

Political internationals

A political international is an organization of political parties or activists with the aim of co-ordinating their activity for a common purpose. There had been a long tradition of socialists organizing on an international basis, and Karl Marx had led the International Workingmen's Association, which later became known as the First International.

After the International Workingmen's Association disbanded in 1876, several attempts were made to revive the organization, culminating the formation of the socialist Second International. This, in turn, was disbanded in 1916 following disagreements over World War I. Although the organization reformed in 1923 as the Labour and Socialist International, supporters of the October Revolution and the Bolsheviks had already set up the Comintern (Communist International), which they regarded as the Third International.[4] This was organized on a democratic centralist basis, with component parties required to fight for policies adopted by the body as a whole.

By declaring themselves the Fourth International, the "World Party of Socialist Revolution," the Trotskyists were publicly asserting their continuity with the Comintern, and with its predecessors. However, their recognition of the importance of these earlier Internationals was coupled with a belief that they had eventually strayed from the socialist path. Although the Socialist International and Comintern were still in existence, the Trotskyists did not believe those organizations were capable of supporting revolutionary socialism and internationalism.[5]

The foundation of the Fourth International was therefore spurred in part by a desire to form a stronger political current, rather than being seen as the communist opposition to the Comintern and the Soviet Union. Trotsky believed that its formation was all the more urgent for the role he saw it playing in the impending World War.[1]

Decision to form the International

Trotsky and his supporters had been organized since 1923 as the Left Opposition, and later the International Left Opposition, an opposition within the Comintern. They opposed the bureaucratization of the Soviet Union, which they analyzed as being partly caused by the poverty and isolation of the Soviet economy.[5] Stalin's theory of socialism in one country was developed in 1924 as an opposition to Trotsky's Theory of Permanent Revolution, which argued that capitalism was a world system and required a world revolution in order to replace it with socialism. Prior to 1924, the Bolshevik's international perspective had been guided by Trotsky's position. Trotsky argued that Stalin's theory represented the interests of bureaucratic elements in direct opposition to the working class.

In the early 1930s, Trotsky and his supporters believed that Stalin's influence over the Third International could still be fought from within and slowly rolled back. They organized themselves into the International Left Opposition in 1930, which was intended to be a group of anti-Stalinist dissenters within the Third International. Stalin's supporters, who dominated the International, would no longer tolerate dissent. All Trotskyists, and those suspected of being influenced by Trotskyism, were expelled.[6]

Trotsky claimed that the Third Period policies of the Comintern had contributed to the rise of Adolf Hitler in Germany, and that its turn to a popular front policy (aiming to unite all ostensibly anti-fascist forces) sowed illusions in reformism and pacifism and "clear[ed] the road for a fascist overturn." By 1935 he claimed that the Comintern had fallen irredeemably into the hands of the Stalinist bureaucracy.[7] He and his supporters, expelled from the Third International, participated in a conference of the London Bureau of socialist parties outside both the Socialist International and the Comintern. Three of those parties joined the Left Opposition in signing a document written by Trotsky calling for a Fourth International, which became known as the "Declaration of Four." Of those, two soon distanced themselves from the agreement, but the Dutch Revolutionary Socialist Party worked with the International Left Opposition to declare the International Communist League.[8]

This position was contested by Andrés Nin and some other members of the League who did not support the call for a new International. This group prioritized regroupment with other communist oppositions, principally the International Communist Opposition (ICO), linked to the Right Opposition in the Soviet Party, a regroupment which eventually led to the formation of the International Bureau for Revolutionary Socialist Unity. Trotsky considered those organizations to be centrist. Despite Trotsky, the Spanish section merged with the Spanish section of ICO, forming the POUM. Trotsky claimed the merger was to be a capitulation to centrism.[9] The Socialist Workers' Party of Germany, a left split from the Socialist Party of Germany founded in 1931, co-operated with the International Left Opposition briefly in 1933 but soon abandoned the call for a new International.

In 1935, Trotsky wrote an Open Letter for the Fourth International, reaffirming the Declaration of Four, while documenting the recent course of the Comintern and the Socialist International. In the letter, he called for the urgent formation of a Fourth International.[8] The "First International Conference for the Fourth International" was held in Paris in June 1936, reports giving its location as Geneva for security reasons.[10] This meeting dissolved the International Communist League, founding in its place the Movement for the Fourth International on Trotsky's perspectives.

The foundation of the Fourth International was seen as more than just the simple renaming of an international tendency that was already in existence. It was argued that the Third International had now degenerated completely and was therefore to be seen as a counter-revolutionary organization that would in time of crisis defend capitalism. Trotsky believed that the coming World War would produce a revolutionary wave of class and national struggles, rather as the First World War had done.[1]

Stalin reacted to the growing strength of Trotsky's supporters with a major political massacre of people within the Soviet Union, and the assassination of Trotsky's supporters and family abroad.[11] He had agents go through historical documents and photos in order to attempt to erase Trotsky's memory from the history books.[12] Stalin's daughter later claimed that his fight with Trotsky laid the foundations for his later anti-semitic campaigns.[13]

Founding Congress

The International's rationale was to construct new mass revolutionary parties able to lead successful workers' revolutions. It saw these arising from a revolutionary wave which would develop alongside and as a result of the coming World War. Thirty delegates attended a founding conference, held in September 1938, in the home of Alfred Rosmer just outside Paris. Present at the meeting were delegates from all the major countries of Europe, and from North America, although for reasons of cost and distance, few delegates attended from Asia or Latin America. An International Secretariat was established, with many of the day's leading Trotskyists and most countries in which Trotskyists were active represented.[14] Among the resolutions adopted by the conference were the Transitional Programme.[15]

The Transitional Programme was the central programmatic statement of the congress, summarizing its strategic and tactical conceptions for the revolutionary period that it saw opening up as a result of the war which Trotsky had been predicting for some years. It is not, however, the definitive program of the Fourth International—as is often suggested—but instead contains a summation of the conjunctural understanding of the movement at that date and a series of transitional policies designed to develop the struggle for workers' power.[16]

World War II

At the outbreak of World War II, in 1939, the International Secretariat was moved to New York City. The resident International Executive Committee failed to meet, largely because of a struggle in the U.S. Socialist Workers Party (SWP) between Trotsky's supporters and the tendency of Max Shachtman, Martin Abern and James Burnham. The secretariat was composed of those committee members who happened to be in the city, most of who were co-thinkers of Shachtman.[17] The disagreement was centered around the Shachtmanites' disagreements with the SWP's internal policy,[18] and over the FI's unconditional defense of the USSR.[19]

Trotsky opened a public debate with Shachtman and Burnham and developed his positions in a series of polemics written in 1939–1940 and later collected in In Defense of Marxism. Shachtman and Burnham's tendency resigned from the International in early 1940, alongside almost 40% of the SWP's members, many of whom became founder members of the Workers Party.[20]

Emergency Conference

In May 1940 an emergency conference of the International met at a secret location "somewhere in the Western Hemisphere." It adopted a manifesto drafted by Trotsky shortly before his murder and a range of on the work of the International, including one calling for the reunification of the then-divided Fourth Internationalist groups in Britain.[21]

Secretariat members who had supported Shachtman were expelled by the emergency conference, with the support of Trotsky himself.[22] While leader of the SWP James P. Cannon later said that he did not believe the split to be definitive and final, the two groups did not reunite.[20] A new International Executive Committee was appointed, which came under the increasing influence of the Socialist Workers Party.[22]

The Fourth International was hit hard during World War II. Trotsky was assassinated, many of the FI's European affiliates destroyed by the Nazis and several of its Asian affiliates destroyed by the Empire of Japan. The survivors, in Europe, Asia and elsewhere, were largely cut off from each other and from the International Secretariat. The new secretary, Jean Van Heijenoort (also known as Gerland), was able to do little more than publish articles in the SWP's theoretical journal Fourth International.[22] Despite this dislocation, the various groups sought to maintain links and some connections were kept up throughout the early part of the war by sailors enlisted in the U.S. Navy who had cause to visit Marseille.[23] Contact was steady, if irregular, between the SWP and the British Trotskyists, with the result that the Americans exerted what influence they had to encourage the Workers' International League into the International through a fusion with the Revolutionary Socialist League, a union that had been requested by the Emergency Conference.[24]

In 1942, a debate on the national question in Europe opened up between the majority of the SWP and a current around Van Heijenoort, Albert Goldman and Felix Morrow.[25] This minority anticipated that the Nazi dictatorship would be replaced with capitalism rather than by a socialist revolution, leading to the revival of Stalinism and social democracy. In December 1943, they criticized the SWP's view as underestimating the rising prestige of Stalinism and the opportunities for the capitalists to use democratic concessions.[26] The SWP's central committee argued that democratic capitalism could not revive, resulting in either military dictatorship by the capitalists or a workers' revolution.[27] It held that this would reinforce the need for building the Fourth International, and adhered rigidly to their interpretation of Trotsky's works.

European Conference

The wartime debate about post-war perspectives was accelerated by the resolution of the February 1944 European Conference of the Fourth International. The conference appointed a new European Secretariat and elected Michel Raptis, a Greek resident in France also known as Michel Pablo, the organizational secretary of its European Bureau. Raptis and other bureau members re-established contact between the Trotskyist parties. The European conference extended the lessons of a revolution then unfolding in Italy, and concluded that a revolutionary wave would cross Europe as the war ended.[28] The SWP had a similar perspective.[29] The British Revolutionary Communist Party disagreed and held that capitalism was not about to plunge into massive crisis but rather that an upturn in the economy was already underway.[30] A group of leaders of the French Internationalist Communist Party around Yvan Craipeau argued a similar position until they were expelled from the PCI in 1948.[31]

International Conference

In April 1946 delegates from the principal European sections and a number of others attended a "Second International Congress."[32] This set about rebuilding the International Secretariat of the Fourth International with Michel Raptis appointed Secretary and Ernest Mandel, a Belgian, taking a leading role.

Pablo and Mandel aimed to counter the opposition of the majorities inside the British Revolutionary Communist Party (RCP) and French Internationalist Communist Party (PCI). Initially, they encouraged party members to vote out their leaderships. They supported Gerry Healy's opposition in the RCP. In France, they backed elements, including Pierre Frank and Marcel Bleibtreu, opposed to the new leadership of the PCI–albeit for differing reasons.[33]

The Stalinist occupation of Eastern Europe was the issue of prime concern, and it raised many problems of interpretation. At first, the International held that, while the USSR was a degenerated workers' state, the post-WWII East European states were still bourgeois entities, because revolution from above was not possible, and capitalism persisted.[34]

Another issue that needed to be dealt with was the possibility that the economy would revive. This was initially denied by Mandel (who was quickly forced to revise his opinion, and later devoted his PhD dissertation to late capitalism, analyzing the unexpected "third age" of capitalist development). Mandel's perspective mirrored uncertainty at that time about the future viability and prospects of capitalism, not just among all Trotskyist groups, but also among leading economists. Paul Samuelson had envisaged in 1943 the probability of a "nightmarish combination of the worst features of inflation and deflation," worrying that "there would be ushered in the greatest period of unemployment and industrial dislocation which any economy has ever faced."[35] Joseph Schumpeter for his part claimed that "The general opinion seems to be that capitalist methods will be unequal to the task of reconstruction." He regarded it as "not open to doubt that the decay of capitalist society is very far advanced".[36]

Second World Congress

The Second World Congress in April 1946 was attended by delegates from 22 sections. It debated a range of resolutions on the Jewish Question, Stalinism, the colonial countries and the specific situations facing sections in certain countries.[37] By this point the FI was united around the view that the Eastern European "buffer states" were still capitalist countries.[38]

The Congress was especially notable for bringing the International into much closer contact with Trotskyist groups from across the globe. These included such significant groups as the Revolutionary Workers' Party of Bolivia and the Lanka Sama Samaja Party in what was then Ceylon,[39] but the previously large Vietnamese Trotskyist groups had mostly been eliminated or absorbed by the supporters of Ho Chi Minh.[40]

After the Second World Congress in 1948, the International Secretariat attempted to open communications with Tito's regime in Yugoslavia.[41] In their analysis, it differed from the rest of the Eastern Bloc because it was established by the partisans of World War II who had fought against Nazi occupation, as opposed to by Stalin's invading armies. The British RCP, led by Jock Haston and supported by Ted Grant, were highly critical of this move.[33]

Third World Congress

The Third World Congress in 1951 resolved that the economies of the East European states and their political regimes had come to resemble that of the USSR more and more. These states were then described as deformed workers states in an analogy with the degenerated workers state in Russia. The term deformed was used rather than degenerated, because no workers' revolution had led to the foundation of these states.[42]

The Third World Congress envisaged the real possibility of an "international civil war" in the near future.[43] It argued that the mass Communist parties "may, under certain favorable conditions, go beyond the aims set for them by the Soviet bureaucracy and project a revolutionary orientation." Given the supposed closeness of war, the FI thought that the Communist Parties and social democratic parties would be the only significant force that could defend the workers of the world against the imperialist camp in those copies where they were mass forces.[44]

In line with this geopolitical perspective, Pablo argued that the only way the Trotskyists could avoid isolation was for various sections of the Fourth International to undertake long-term entryism in the mass Communist or Social Democratic parties.[45] This tactic was known as entrism sui generis, to distinguish it from the short-term entry tactic employed before [[World War II]. For example, it meant that the project of building an open and independent Trotskyist party was shelved in France, because it was regarded as not politically feasible alongside entry into the French Communist Party.

This perspective was accepted within the Fourth International, yet sowed the seeds for the split in 1953. At the Third World Congress, the sections agreed with the perspective of an international civil war. The French section disagreed with the associated tactic of entryism sui generis, and held that Pablo was underestimating the independent role of the working class parties in the Fourth International. The leaders of the majority of the Trotskyist organization in France, Marcel Bleibtreu and Pierre Lambert, refused to follow the line of the International. The International leadership had them replaced by a minority, leading to a permanent split in the French section.[46]

In the wake of the World Congress, the line of the International Leadership was generally accepted by groups around the world, including the U.S. SWP whose leader, James P. Cannon, corresponded with the French majority to support the tactic of entrism sui generis.[46] At the same time, however, Cannon, Gerry Healy and Ernest Mandel were deeply concerned by Pablo's political evolution. Cannon and Healy were also alarmed by Pablo's intervention into the French section, and by suggestions that Pablo might use the International's authority in this way in other sections of the Fourth International that felt entrism "sui generis" was not a suitable tactic in their own countries. In particular, minority tendencies in Britain around John Lawrence and the U.S. around Bert Cochran that supported entrism "sui generis" hinted that Pablo's support for their views indicated that the International might also demand Trotskyists in those countries adopt that tactic.[47]

Formation of the International Committee of the Fourth International

In 1953, the SWP's national committee issued an Open Letter to Trotskyists Throughout the World and organized the International Committee of the Fourth International (ICFI). This was a public faction which initially included, in addition to the SWP, Gerry Healy's British section The Club, the Internationalist Communist Party in France (then led by Lambert who had expelled Bleibtreu and his grouping), Nahuel Moreno's party in Argentina and the Austrian and Chinese sections of the FI. The sections of the ICFI withdrew from the International Secretariat, which suspended their voting rights. Both sides claimed they constituted a majority of the former International.[48]

Sri Lanka's Lanka Sama Samaja Party, then the country's leading workers' party, took a middle position during this dispute. It continued to participate in the ISFI but argued for a joint congress, for reunification with the ICFI.[49]

An excerpt from the Open Letter explains the split as follows:

To sum up: The lines of cleavage between Pablo's revisionism and orthodox Trotskyism are so deep that no compromise is possible either politically or organizationally. The Pablo faction has demonstrated that it will not permit democratic decisions truly reflecting majority opinion to be reached. They demand complete submission to their criminal policy. They are determined to drive all orthodox Trotskyists out of the Fourth International or to muzzle and handcuff them. Their scheme has been to inject their Stalinist conciliationism piecemeal and likewise in piecemeal fashion, get rid of those who come to see what is happening and raise objections.[50]

From the Fourth World Congress to reunification

Over the following decade, the IC referred to the rest of the International as the International Secretariat of the Fourth International, emphasizing its view that the Secretariat did not speak for the International as a whole.[51] The Secretariat continued to view itself as the leadership of the International. It held a Fourth World Congress in 1954 to regroup and to recognize reorganized sections in Britain, France and the U.S.

Parts of the International Committee were divided over whether the split with "Pabloism" was permanent or temporary,[52] and it was perhaps as a result of this that it did not declare itself to be the Fourth International. Those sections that considered the split permanent embarked on a discussion about the history of the split and its meanings.

The sections of the International that recognized the leadership of the International Secretariat remained optimistic about the possibilities for increasing the International's political influence and extended the entrism into Social Democratic Parties which was already underway in Britain, Austria and elsewhere. The 1954 congress emphasized entrism into Communist Parties as well as Nationalist parties in the colonies, pressing for democratic reforms, ostensibly to encourage the left-wing they perceived to exist in the Communist Parties to join with them in a revolution.[53] Tensions developed between the mainstream around Pablo and a minority that argued unsuccessfully against open work. A number of these delegates walked out of the World Congress, and would eventually leave the International, including the leader of the new British section, John Lawrence, George Clarke, Michele Mestre (a leader of the French section), and Murray Dowson (a leader of the Canadian group).[54]

The Secretariat organized a Fifth World Congress in October 1957. Mandel and Pierre Frank appraised the Algerian revolution and surmised that it was essential to reorient in the colonial states and neocolonies towards the emerging guerrilla-led revolutions.[55]

The Sixth World Congress in 1961 marked a lessening of the political divisions between the majority of supporters of the International Secretariat and the leadership of the SWP in the United States. In particular, the congress stressed support for the Cuban revolution and a growing emphasis on building parties in the imperialist countries. The sixth congress also criticised the Lanka Sama Samaja Party, its Sri Lankan section, for seeming to support the Sri Lanka Freedom Party, which they saw as bourgeois nationalists; the U.S. SWP made similar criticisms. The supporters of Michel Pablo and Juan Posadas opposed the convergence. The supporters of Posadas left the International in 1962.[56]

In 1962 the IC and IS formed a Parity Commission to organize a common World Congress. At the 1963 congress, a split in the IC took place, with a significant part centered on the U.S. SWP agreeing to reunify with the IS. This was largely a result of their mutual support for the Cuban Revolution, based on Ernest Mandel and Joseph Hansen's resolution Dynamics of World Revolution Today. This document distinguished between different revolutionary tasks in the imperialist countries, the "workers' states," and the colonial and semi-colonial countries.[57] In 1963, the reunified Fourth International elected a United Secretariat of the Fourth International (USFI), by which name the organization as a whole is often still referred.

Unity discussions after 1963

Lambert's Internationalist Communist Party (PCI) in France and the Socialist Labour League (SLL) in Britain did not take part in the reunification congress, but discussions continued on the topic. The PCI and SLL maintained the ICFI under their own leadership, opposing key elements in the reunification documents, including the view that the July 26 Movement has created a workers' state in Cuba. They argued instead that Cuba's revolution did not bring power to the working class; the SLL believed that Cuba had remained a capitalist country.[58] In their view, the United Secretariat's support for the Cuban and Algerian leaderships reflected a lack of commitment to the building of revolutionary Marxist parties. While not rejecting reunification in itself, the continuing ICFI argued that a deeper political discussion was needed to ensure that Pablo's errors were not deepened.[59]

Led by Tim Wohlforth and James Robertson, those within the U.S. Socialist Workers Party (SWP), who broadly shared this view formed a "Revolutionary Tendency" in 1962. They argued that the party should have a full discussion of the meaning of Pabloism and the 1953 split. Along with the remainder of the ICFI, they argued that Cuba's revolution did not prove that the Fourth International was no longer necessary in the colonial countries. However, differences inside the Revolutionary Tendency developed.[60] In 1964, with Wohlforth laying the evidentiary basis for claims of "party disloyalty" against Robertson, the tendency was expelled from the party. In the opinion of Robertson's group, Wohlforth conspired with the SWP leadership to get Robertson's group expelled.[61]

The ICFI unsuccessfully repeated its appeal for a deep discussion with the reunified Fourth International at the end of 1963, and on later occasions.[62] Its 1966 conference called for a Fourth International Conference.[63] The ICFI approached the USFI again in 1970, requesting "a mutual discussion that might open the way to the Socialist Labour League and its French sister organization, the Trotskyist Organisation, reunifying with the Fourth International".[64] Similar approaches were rejected in 1973.[65]

After the Lambert's current left the ICFI in 1971, its Organizing Committee for the Reconstruction of the Fourth International (OCRFI) opened discussion with the USFI. In May 1973, Lambert's tendency unsuccessfully requested to take part in the discussions for the USFI's 1974 congress, but the United Secretariat did not take the letter at face value and asked for clarification. In September 1973 the OCRFI responded positively and the United Secretariat agreed a positive reply. However, in the rush of preparations for the world congress the United Secretariat's letter was not sent, leading Lambert's group to repeat its request in September 1974 through an approach to the US SWP. The following month the USFI organized a meeting with the OCRFI. However, discussions decelerated after Lambert's Internationalist Communist Organization made an attack on Ernest Mandel, which it later acknowledged as an error. In 1976 new approaches by the OCRFI met with success, when it wrote with the aim "to strengthen the force of the Fourth International as a single international organization." However, these discussions decelerated again in 1977 after the Internationalist Communist Organization leaders stated that it had members inside the Revolutionary Communist League, the USFI's French section.[66]

Other currents with roots in Gerry Healy's ICFI also came towards the United Secretariat at this time: the Workers Socialist League in Britain and the Socialist League in Australia both opened discussions in 1976.[67] Both currents would eventually merge with the sections of the International in their countries; the Socialist League merging in 1977, while the majority of the Workers Socialist League became the Socialist Group, which was to attend the ninth world congress and eventually join in 1987.

Unification was also discussed between the USFI and the French group Lutte Ouvriere. In 1970, Lutte Ouvriere initiated fusion discussions with the French section of the USFI. After extensive discussions, the two organizations agreed the basis for a fused organization, but the fusion was not completed. In 1976 discussions between the USFI and Lutte Ouvriere progressed again. The two organizations started to produce a common weekly supplement to their newspapers, common electoral work and other common campaigning.[68]

Michel Pablo's tendency also raised the question of unity in 1976, with an ambitious proposal that it and the USFI could eventually unify in a new organization comprising tendencies that were, or were evolving towards, revolutionary Marxism. The USFI felt unable to move ahead with the proposal.[69] Pablo's tendency finally rejoined in 1995.

The International today

Since the 1963 reunification, a number of approaches have developed within international Trotskyism towards the Fourth International.

- The reunified Fourth International (sometimes known as the United Secretariat of the Fourth International or USFI) is the only current with direct organizational continuity to the original Fourth International at an international level. The 1963 congress reunified the majorities of all but two of the national sections of the Fourth International. It is also the only current to have continuously presented itself as "the" Fourth International. It is the largest current and leaders of some other Trotskyist Internationals occasionally refer to it as "the Fourth International." The International Socialist Tendency also usually refers to it in this way but does not accept that the FI can claim political continuity with the FI of Trotsky.[70]

- The International Committee of the Fourth International member groups customarily describe themselves as sections of the Fourth International, and the organization as whole describes itself as the "leadership of the Fourth International." However, the ICFI presents itself as the political continuity of the Fourth International and Trotskyism, not as the FI itself. It clearly dates its creation as 1953, rather than from 1938.[71]

- Some tendencies argue that the Fourth International became dislocated politically during the years between Trotsky's murder and the establishment of the ICFI in 1953; they consequently work to "reconstruct," "reorganize" or "rebuild" it. This view originated with Lutte Ouvriere and the international Spartacist tendency and is shared by others who diverged from the ICFI. For example, the Committee for a Workers International, whose founders dropped out of the reunified FI after 1965, call for a new "revolutionary Fourth International".[72]

Impact

In uniting the large majority of Trotskyists in one organization, the Fourth International created a tradition which has since been claimed by many Trotskyist organizations.

Echoing Marx's Communist Manifesto, the Transitional Programme ended with the declaration "Workers—men and women—of all countries, place yourselves under the banner of the Fourth International. It is the banner of your approaching victory!." It declared demands to be placed on capitalists, opposition to the bureaucracy in the Soviet Union, and support for workers' action against fascism.[1] Most of the demands on capitalists remain unfulfilled. The collapse of the Soviet Union occurred, but through a social revolution leading to the restoration of capitalism, rather than the political revolution proposed by the Trotskyists. Many Trotskyist groups have been active in anti-fascist campaigns, but the Fourth International has never played a major role in the toppling of a regime.

Those groups which follow traditions that left the Fourth International in its early years argue that, despite initially correct positions, it had little impact. Workers Liberty, which follows in the third camp tradition established by the Workers Party, holds that "Trotsky and everything he represented was defeated and—as we have to recognize in retrospect—defeated for a whole historical period."[73]

Other groups point to a positive impact. The ICFI claim that "the [early] Fourth International consisted mainly of cadres who remained true to their aims"[74] and describes much of the Fourth International's early activity as "correct and principled."[75] The reunified FI claim that "the Fourth International refused to compromise with capitalism either in its fascist or democratic variants." In its view, "many of the predictions made by Trotsky when he founded the Fourth International were proved wrong by history. But what was absolutely vindicated were his key political judgments."[76]

Notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 Leon Trotsky The Transitional Program. Maxists.org. Retrieved July 28, 2016.

- ↑ Ernest Mandel, Trotskyists and the Resistance in World War Two. Retrieved July 28, 2016.

- ↑ Leon Trotsky, In Defense of October. Retrieved July 28, 2016.

- ↑ Working-class Internationalism & Organization. Retrieved July 28, 2016.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Manifesto of the Fourth International on the Dissolution of the Comintern. Retrieved July 28, 2016.

- ↑ J. V. Stalin, Industrialisation of the country and the right deviation in the C.P.S.U.(B.). Retrieved July 28, 2016.

- ↑ Leon Trotsky, Open Letter For The Fourth International, Spring 1935. Retrieved July 28, 2016.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 George Breitman, The Rocky Road to the Fourth International, 1933-38. Retrieved July 28, 2016.

- ↑ John G. Wright, Trotsky's Struggle for the Fourth International, August 1946. Retrieved July 28, 2016.

- ↑ CLR James and British Trotskyism Retrieved July 28, 2016.

- ↑ Trotskyists at Vorkuta: An Eyewitness Report International Socialist Review, Summer 1963. Retrieved July 28, 2016.

- ↑ Propaganda in the Propaganda State, PBS. Retrieved July 28, 2016.

- ↑ Arnold Beichman, How Stalin, the 'breaker of nations,' hated, murdered Jews, Washington Times, August 16, 2003. Retrieved July 28, 2016.

- ↑ Founding Conference of the Fourth International, 1938. Retrieved July 28, 2016.

- ↑ Socialist Workers Party (US), The Founding Conference of the Fourth International, 1938. Program and Resolutions. Retrieved July 28, 2016.

- ↑ Richard Price, The Transitional Programme in perspective. Retrieved July 28, 2016.

- ↑ Declaration on the status of the resident International Executive Committee, in Documents of the Fourth International, Vol 1, 351–355. Retrieved July 28, 2016.

- ↑ Duncan Hallas, Fourth International in Decline. Retrieved July 28, 2016.

- ↑ Leon Trotsky, In Defence of Marxism. Retrieved July 28, 2016.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 James P. Cannon, Factional Struggle And Party Leadership, Fourth International, November-December, 1953. Retrieved July 28, 2016.

- ↑ Emergency Conference of the Fourth International, On the Eve of World War II: May 1940. Retrieved July 28, 2016.

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 22.2 Michel Pablo, Report on the Fourth International Since the Outbreak of War, 1939-48, December 1948 and January 1949. Retrieved July 28, 2016.

- ↑ Rodolphe Prager, The Fourth International during the Second World War. Retrieved July 28, 2016.

- ↑ Resolution On The Unification of the British Section, Fourth International, May 19-26, 1940. Retrieved July 28, 2016.

- ↑ The Fourth International During World War II (immediately afterwards). Retrieved July 28, 2016.

- ↑ Felix Morrow, The First Phase of the Coming European Revolution, December 1943. Retrieved July 28, 2016.

- ↑ Perspectives and Tasks of the Coming European Revolution, November 2, 1943. Retrieved July 28, 2016.

- ↑ Theses on the Liquidation of World War II and the Revolutionary Upsurge, February 1944. Retrieved July 28, 2016.

- ↑ The European Revolution and the Tasks of the Revolutionary Party, New York, December, 1944. Retrieved July 28, 2016.

- ↑ Martin Upham, The History of British Trotskyism to 1949. Retrieved July 28, 2016.

- ↑ Peter Schwarz, The politics of opportunism: the "radical left" in France, May 22, 2004. Retrieved July 28, 2016.

- ↑ The Conference of the Fourth International, June 1946. Retrieved July 28, 2016.

- ↑ 33.0 33.1 Sam Bornstein and Al Richardson, War and the International (Socialist Platform Ltd, 1986, ISBN 978-0950842332).

- ↑ [Alex Callinicos, Trotskyism. Retrieved July 28, 2016.

- ↑ "Full Employment after the war," in Seymour Harris (ed.), Post war Economic Problems (McGraw-Hill Book Company, 1943, ASIN B000L9X6JC).

- ↑ "Capitalism in the post-war world" in Seymour Harris (ed.), Post war Economic Problems (McGraw-Hill Book Company, 1943, ASIN B000L9X6JC).

- ↑ 2nd Congress of the Fourth International, 1948. Retrieved July 28, 2016.

- ↑ The USSR and Stalinism Resolution Adopted by the Second Congress of the Fourth International—Paris, April 1948. Retrieved July 28, 2016.

- ↑ The Third World Congress of the Fourth International. Retrieved July 28, 2016.

- ↑ The Fourth International in Vietnam Retrieved July 28, 2016.

- ↑ International Secretariat of the Fourth International, An Open Letter to Congress, Central Committee and Members of the Yugoslav Communist Party, July 1948. Retrieved July 28, 2016.

- ↑ Pierre Frank, Evolution of Eastern Europe, August 1951. Retrieved July 28, 2016.

- ↑ Theses on Orientation and Perspectives, Resolution Adopted by the Third Congress of the Fourth International—Paris, April 1951. Retrieved July 28, 2016.

- ↑ The International Situation and Tasks in the Struggle against Imperialist War, Resolution Adopted by the Third Congress of the Fourth International—Paris, April 1951. Retrieved July 28, 2016.

- ↑ Michel Pablo, World Trotskism Rearms, November 1951. July 28, 2016.

- ↑ 46.0 46.1 Letters exchanged between Daniel Renard and James P. Cannon, February 16 and May 9, 1952. Retrieved July 28, 2016.

- ↑ International Committee Documents 1951-1954, Vol. 1, Section 4, (Education for Socialists).

- ↑ Resolution forming the International Committee, November 23, 1953. Retrieved July 28, 2016.

- ↑ David North addresses Sri Lankan Trotskyists on the 50th anniversary of the ICFI, November 21, 2003. Retrieved July 28, 2016.

- ↑ James P. Cannon, A Letter to Trotskyists Throughout the World, November 16, 1953. Retrieved July 28, 2016.

- ↑ Resolution of the International Committee instructing publication of the documents, August 24, 1973, Workers Press, August 29, 1973. Retrieved July 28, 2016.

- ↑ Letter from the International Secretariat "to all Members and All Organizations of the International Committee", July 1955. Retrieved July 28, 2016.

- ↑ Michel Pablo, The Post-Stalin "New Course", July 1953. Retrieved July 28, 2016.

- ↑ John McIlroy, The Revolutionary Odyssey of John Lawrence, What Next. Retrieved July 28, 2016.

- ↑ Pierre Frank, The Fourth International: The Long March of the Trotskyists. Retrieved July 28, 2016.

- ↑ Trotskyism and the Cuban Revolution: A Debate, What Next. Retrieved July 28, 2016.

- ↑ Dynamics of World Revolution Today, 1963. Retrieved July 28, 2016.

- ↑ Cliff Slaughter in Labour Review, Summer 1962

- ↑ Trotskyism Betrayed: The SWP accepts the political method of Pabloite revisionism, 1962, Socialist Labour League

- ↑ "Call for the reorganization of the minority tendency in the SWP," Trotskyism versus Revisionism, Vol. 4

- ↑ Harry Turner in Marxism versus Ultraleftism, pp 89

- ↑ Gerry Healy, Letter of 27 September, Trotskyism versus Revisionism, Vol. 4

- ↑ Resolution in Trotskyism versus Revisionism, Vol. 5

- ↑ Bob Pitt, Gerry Healy—Rise and Fall, What Next? Retrieved July 28, 2016.

- ↑ Jack Barnes, letter in Trotskyism versus Revisionism, Vol. 5

- ↑ SWP US International Internal Discussion Bulletin, Vol XIV, No. 3, pp 32, 1977

- ↑ Mary-Alice Waters in SWP US International Internal Discussion Bulletin, Vol XIV, No. 2, pp 31, 1977

- ↑ SWP US International Internal Discussion Bulletin, Vol XIV, No. 3, pp 34–5, 1977

- ↑ Mary-Alice Waters in SWP US International Internal Discussion Bulletin, Vol XIV, No. 2, pp 33, 1977

- ↑ International Socialist Tendency. Retrieved July 28, 2016.

- ↑ Peter Schwarz, Meetings on 50 years of the International Committee of the Fourth International, December 6, 2003. Retrieved July 28, 2016.

- ↑ Peter Taaffe, A Socialist World is Possible: The history of the CWI, Committee for a Workers International.

- ↑ Sean Matgamna, What we are, what we do and why we do it, May 3, 2005. Retrieved July 28, 2016.

- ↑ Peter Schwarz, The politics of opportunism: the “radical left” in France June 4, 2004. Retrieved July 28, 2016.

- ↑ David North, Ernest Mandel, 1923-1995: A critical assessment of his role in the history of the Fourth International (Mehring Books, 1997).

- ↑ Fourth International - Impact. Retrieved July 28, 2016.

References

ISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Alexander, Robert J. International Trotskyism, 1929-1985: A Documented Analysis of the Movement. Duke University Press, 1991. ISBN 978-0822310662

- Irish Workers Group. Death Agony of the Fourth International and the tasks of Trotskyists Today. Workers Power, 1983. ISBN 978-0950813318

- Mandel, Ernest. The Reasons for Founding the Fourth International And Why They Remain Valid Today. Retrieved September 26, 2022.

- Moreau, Francois. Combats et débats de la Quatrième Internationale. Québec, Vents d'Ouest, 1993. ISBN 978-2921603096

- North, David The Heritage We Defend. Detroit, MI: Labor Publications, 1988. ISBN 978-0929087009

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.

↧ Download as ZWI file | Last modified: 02/04/2023 03:59:00 | 14 views

☰ Source: https://www.newworldencyclopedia.org/entry/Fourth_International | License: CC BY-SA 3.0

ZWI signed:

ZWI signed:

KSF

KSF