Amun

From Conservapedia

From Conservapedia Amun is one of the most prominent gods of the Egyptian pantheon, who became, in combination with Ra (as Amun-Ra), the dominant state god of the Ancient Egyptian New Kingdom.

Contents

Nature and Chacteristics[edit]

Amun is one of the most well known yet also most shadowy of the Egyptian gods. Despite being supreme state god his role is far from clear cut. Originally a god associated with the wind, he was regarded as an unknowable, hidden deity, and his name reflects this, imn literally translating as “hide”. His association with the wind remains alongside his other roles, following his rise to prominence, as does his essentially hidden characteristic. He remains “mysterious of form”.

As supreme state god, Amun-Ra took on most aspects of the sun god, including his role as King of the Gods, and many solar connotations. He also adopted many aspects of the cult of the fertility god Min, in his combined form of Amun-Min, usually portrayed as an ityphallic male.

Most importantly, in the New Kingdom he was regarded as one of the divine fathers of the Pharaoh, and is featured in the “birth scenes” of the period, depicting the divine conception and birth of the Pharaoh.

His prominence in state religion did not dent his popularity in common religion, and he is frequently referred to in prayers as the protector of the common man and the unfortunate. He is described as the “Vizier of the Humble” and “He Who Comes at the Voice of the Poor”. In his role as Amun-of-the-road he also protected travellers.

Imagery[edit]

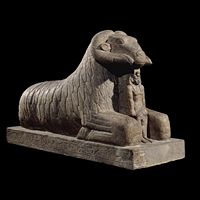

Amun was most often depicted as a human male, often wearing a crown featuring two plumes. As Amun-Ra a sun disc is added to the crown, symbolising his association with the sun god. Amun was also associated with the ram, and so could be depicted as a ram or with a rams head and horns. Rams horns could also be added to his crown in human form. A large number of ram headed sphinxes have been excavated at Karnak, where they embellished the avenue leading from the precinct of Amun-Ra to the temple harbour, and remain more or less in-situ today.

Origins and Rise to Prominence[edit]

Despite his rise to national prominence, the cult of Amun was Theban in origin, and Thebes always remained his main cult centre, even following his association with Ra, and Amun-Ra as a combined deity was never worshipped at the cult centre of Ra in Heliopolis.

First mentioned in the Pyramid Texts, he first comes to prominence in the 11th Dynasty, a period when a Theban dynasty reunified Egypt following the brief but severe chaos of the First Intermediate Period. However, as the Middle Kingdom rulers soon built a new capital city in the north, Amun's power did not reach the status of supreme state god.

Following the division of Egypt between the Hyksos occupiers and the Theban Kingdom, the Thebans once again reunified Egypt, and Thebes became one of the foremost religious centres in Egypt. As Egypt had been reunified so the union of Amun with the cult of Ra from the (northern) city of Heliopolis was also cemented, and Amun-Ra quickly became the pre-eminent state god. The 18th Dynasty Pharaohs again had names associating them with Amun, and the estates of the god soon became the largest and wealthiest in Egypt, the fortunes bolstered by a generous share of the spoils of war captured by the Empire, and the flows of tribute that followed.

The influence of Amun soon spread into some of the new territories, particularly Kush, where his influence soon became so pervasive, that his cult there remained powerful and influential centuries after the departure of the Pharaoh's colonial officials at the end of the 20th Dynasty.

During the 18th Dynasty, Amun became by far the biggest taxpayer in Egypt, and by some modern estimates his estates were responsible for over 25% of the economic activity in Egypt. It is now widely understood by Egyptologists that there was no conflict between Amun and the palace, for the two were essentially the same. The priesthood and the Pharaoh did not constitute two opposing power bases in Egypt, for they were one and the same thing. The Pharaoh was the high priest of every god, and all other priests were merely his representative stand ins for ceremonies. The wealth of Amun was essentially an extension of the state's holdings, and it was understood from the Old Kingdom onwards that all the land and wealth of Egypt ultimately belonged to the Pharaoh.

Repression During the Amarna Heresy[edit]

The Amarna heresy (circa 1353 to 1336 BC) changed the fortunes of Amun at a stroke. Initially tolerant of Amun and other gods besides his one-god, whom he associated with the sun disc (itn, often translated as “Iten”, “Aten”, or in older texts, “Aton”) the heretic ruler Akhenaten (as Amunhotep IV renamed himself) closed down the temples of Amun and all other gods, and confiscated their estates. Amun in particular was then singled out, and all mentions to the god, including many of his images, were crudely hacked from the walls of public and private texts, including in names, and even in private tomb inscriptions.

However, the period was short, and almost immediately following the death of Akhenaten, his successors set about restoring order, rebuilding the shattered empire and it's economy, and restoring the estates of the gods. The cult of Amun-Ra would benefit hugely from subsequent reigns, and Seti I and Ramesses II both added massively to the cult centre of Karnak and Luxor. For the rest of the New Kingdom, Amun-Ra's predominance was assured.

Late Period[edit]

The Late Period was a time of mixed blessings for the cult of Amun. Although Karnak continued to receive embellishments and expansion, the period all saw the rise of the cult of Isis and Osiris, and also previously minor gods such as Bast.

However, outside of Egypt the cult of Amun had remained strong, particularly in Nubia, where Egyptian cultural domination in the New Kingdom had essentially reformed Nubian society in its own image. The southerners, who maintained the zeal of the convert, briefly occupied parts, at times almost all of Egypt, ruling as the 25th Dynasty, greatly reiterating the dominance of Amun-Ra and making specific point of participating and honouring the festivals of the god.

Despite this turn in fortunes, the 30th Dynasty saw the rise to prominence of Isis and Osiris, and these cults would gradually begin to outshine that of Amun-Ra, despite his association by the Ptolemaic rulers of Amun-Ra with Zeus, as Amonra Sonther, a hellenization of his Egyptian title imn-r’ nsw ntrw, literally “Amun-Ra, King of the Gods”.

Temples and Cult Centre[edit]

Karnak was the main cult centre of Amun-Ra, and remains the world's largest religious complex. However, Amun had temples and shrines throughout Egypt and Nubia. In addition many sanctuaries in other temples were also established in his honour. “Amun of the Road” often accompanied military and trade missions abroad, where a sacred image of the god travelled with his own portable shrine. “The Report of Wenamun” makes mention of precisely this form of the god, and his shrine, whom has come with him on a mission to Byblos to obtain timber.

The Theban Triad[edit]

The Theban triad generally consisted of Amun-Ra, his consort Mut, and their son, the lunar deity Khonsu. At Karnak he shared the cult centre with another prominent Theban god, Montu, a good of conflict and war. Amun-Ra, however, remained by far the most prominent god of the triad.

Bibliography[edit]

- Faulkner, R O (1969), The Ancient Egyptian Pyramid Texts, Oxford University Press, Oxford

- Gardiner, A (1973), Egyptian Grammar, Griffith Institute, Oxford

- Newby, P H (1980), Warrior Pharaohs: The Rise and Fall of the Egyptian Empire, Guild, London

- Shaw, I et al. (2000), Oxford History of Ancient Egypt, Oxford University Press, Oxford

- Wilkinson, R (2000), The Complete Temples of Ancient Egypt, Thames & Hudson, London

- Wilkinson, R (2003), The Complete Gods and Goddesses of Ancient Egypt, Thames & Hudson, London

Categories: [Ancient Egypt] [Egyptian Mythology]

↧ Download as ZWI file | Last modified: 02/19/2023 17:39:10 | 148 views

☰ Source: https://www.conservapedia.com/Amun | License: CC BY-SA 3.0

ZWI signed:

ZWI signed:

KSF

KSF