Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma

From Mdwiki

From Mdwiki

| Non-Hodgkin lymphoma | |

|---|---|

| Other names: Non-Hodgkin disease | |

| |

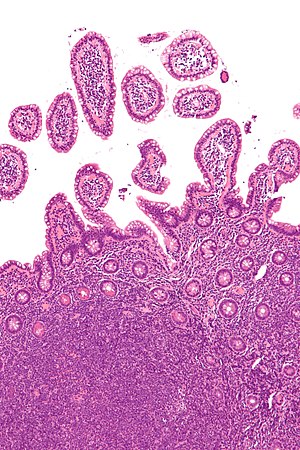

| Micrograph of mantle cell lymphoma, a type of non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Terminal ileum. H&E stain. | |

| Specialty | Hematology and oncology |

| Symptoms | Enlarged lymph nodes, fever, night sweats, weight loss, tiredness, itching[1] |

| Usual onset | 65–75 years old[2] |

| Risk factors | Poor immune function, autoimmune diseases, Helicobacter pylori infection, hepatitis C, obesity, Epstein-Barr virus infection[1][3] |

| Diagnostic method | Bone marrow or lymph node biopsy[1] |

| Treatment | Chemotherapy, radiation, immunotherapy, targeted therapy, stem cell transplantation, surgery, watchful waiting[1] |

| Prognosis | Five-year survival rate 71% (USA)[2] |

| Frequency | 4.3 million (affected during 2015)[4] |

| Deaths | 231,400 (2015)[5] |

Non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL) is a group of blood cancers that includes all types of lymphomas except Hodgkin lymphomas.[1] Symptoms include enlarged lymph nodes, fever, night sweats, weight loss and tiredness.[1] Other symptoms may include bone pain, chest pain or itchiness.[1] Some forms are slow-growing, while others are fast-growing.[1]

Lymphomas are types of cancer that develop from lymphocytes, a type of white blood cell.[2] Risk factors include poor immune function, autoimmune diseases, Helicobacter pylori infection, hepatitis C, obesity, and Epstein–Barr virus infection.[1][3] The World Health Organization classifies lymphomas into five major groups, including one for Hodgkin lymphoma.[6] Within the four groups for NHL are over 60 specific types of lymphoma.[7][8] Diagnosis is by examination of a bone marrow or lymph node biopsy.[1] Medical imaging is done to help with cancer staging.[1]

Treatment depends on whether the lymphoma is slow- or fast-growing and if it is in one area or many areas.[1] Treatments may include chemotherapy, radiation, immunotherapy, targeted therapy, stem-cell transplantation, surgery, or watchful waiting.[1] If the blood becomes overly thick due to high numbers of antibodies, plasmapheresis may be used.[1] Radiation and some chemotherapy, however, increase the risk of other cancers, heart disease, or nerve problems over the subsequent decades.[1]

In 2015, about 4.3 million people had non-Hodgkin lymphoma, and 231,400 died.[4][5] In the United States, 2.1% of people are affected at some point in their life.[2] The most common age of diagnosis is between 65 and 75 years old.[2] The five-year survival rate in the United States is 71%.[2]

Signs and symptoms[edit | edit source]

The signs and symptoms of non-Hodgkin lymphoma vary depending upon its location within the body. Symptoms include enlarged lymph nodes, fever, night sweats, weight loss, and tiredness. Other symptoms may include bone pain, chest pain, or itchiness. Some forms are slow growing, while others are fast growing.[1] Enlarged lymph nodes may cause lumps to be felt under the skin when they are close to the surface of the body. Lymphomas in the skin may also result in lumps, which are commonly itchy, red, or purple. Lymphomas in the brain can cause weakness, seizures, problems with thinking, and personality changes.[medical citation needed]

While an association between non-Hodgkin lymphoma and endometriosis has been described,[9] these associations are tentative.[10]

Causes[edit | edit source]

The many different forms of lymphoma probably have different causes. These possible causes and associations with at least some forms of NHL include:

- Infectious agents:

- Epstein–Barr virus: associated with Burkitt's lymphoma, Hodgkin lymphoma, follicular dendritic cell sarcoma, extranodal NK-T-cell lymphoma[11]

- Human T-cell leukemia virus: associated with adult T-cell lymphoma

- Helicobacter pylori: associated with gastric lymphoma

- HHV-8: associated with primary effusion lymphoma, multicentric Castleman disease

- Hepatitis C virus: associated with splenic marginal zone lymphoma, lymphoplasmacytic lymphoma and diffuse large B-cell lymphoma[12]

- HIV infection[13]

- Some chemicals, like polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs),[14][15][16] diphenylhydantoin, dioxin, and phenoxy herbicides.

- Medical treatments, like radiation therapy and chemotherapy

- Genetic diseases, like Klinefelter syndrome, Chédiak–Higashi syndrome, ataxia–telangiectasia syndrome

- Autoimmune diseases, like Sjögren syndrome, celiac disease, rheumatoid arthritis, and systemic lupus erythematosus.[17][18]

Familial component[edit | edit source]

Familial lymphoid cancer is rare. The familial risk of lymphoma is elevated for multiple lymphoma subtypes, suggesting a shared genetic cause. However, a family history of a specific subtype is most strongly associated with risk for that subtype, indicating that these genetic factors are subtype-specific. Genome-wide association studies have successfully identified 67 single-nucleotide polymorphisms from 41 loci, most of which are subtype specific.[19]

HIV/AIDS[edit | edit source]

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) included certain types of non-Hodgkin lymphoma as AIDS-defining cancers in 1987.[20] Immune suppression rather than HIV itself is implicated in the pathogenesis of this malignancy, with a clear correlation between the degree of immune suppression and the risk of developing NHL. Additionally, other retroviruses, such as HTLV, may be spread by the same mechanisms that spread HIV, leading to an increased rate of co-infection.[21] The natural history of HIV infection has been greatly changed over time. As a consequence, rates of non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL) in people infected with HIV has significantly declined in recent years.[13]

Diagnosis[edit | edit source]

The diagnosis of non-Hodgkin lymphoma can present with involvement of other organs. Accurate disease staging is very important in the diagnostic process.[22]

Treatment[edit | edit source]

The traditional treatment of NHL includes chemotherapy, radiotherapy, and stem-cell transplants.[23][24] There have also been developments in immunotherapy used in the treatment of NHL.[25] The most common chemotherapy used for B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma is R-CHOP, which is a regimen of four drugs (cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone) plus rituximab.[26]

If participants receive stem-cell transplants, they can develop a graft-versus-host disease. It is unclear if mesenchymal stromal cells (MSC) helps with this condition though.[27]

Prognosis[edit | edit source]

Prognosis depends on the subtype, the staging, a person's age, and other factors. Across all subtypes, 5-year survival for NHL is 71%, ranging from 81% for Stage 1 disease to 61% for Stage 4 disease.[28]

Epidemiology[edit | edit source]

Globally, as of 2010, there were 210,000 deaths, up from 143,000 in 1990.[29]

Rates of non-Hodgkin lymphoma increases steadily with age.[17] Up to 45 years NHL is more common among males than females.[30]

Australia[edit | edit source]

With over 6,000 people being diagnosed yearly, NHL is the fifth most common cancer in Australia.[31]

Canada[edit | edit source]

In Canada, NHL is the fifth most common cancer in males and sixth most common cancer in females. The lifetime probability of developing a lymphoid cancer is 1 in 44 for males, and 1 in 51 for females.[32]

United Kingdom[edit | edit source]

On average, according to data for the 2014–2016 period, around 13,900 people are diagnosed with NHL yearly. It is the sixth most common cancer in the UK, and is the eleventh most common cause of cancer death accounting for around 4,900 deaths per year.[33]

United States[edit | edit source]

Age adjusted data from 2012-2016 shows about 19.6 cases of NHL per 100,000 adults per year, 5.6 deaths per 100,000 adults per year, and around 694,704 people living with non-Hodgkin lymphoma. About 2.2 percent of men and women will be diagnosed with NHL at some point during their lifetime.[34]

The American Cancer Society lists non-Hodgkin lymphoma as one of the most common cancers in the United States, accounting for about 4% of all cancers.[35]

History[edit | edit source]

While consensus was rapidly reached on the classification of Hodgkin lymphoma, there remained a large group of very different diseases requiring further classification. The Rappaport classification, proposed by Henry Rappaport in 1956 and 1966, became the first widely accepted classification of lymphomas other than Hodgkin. Following its publication in 1982, the Working Formulation became the standard classification for this group of diseases. It introduced the term non-Hodgkin lymphoma or NHL and defined three grades of lymphoma.[citation needed]

NHL consists of many different conditions that have little in common with each other. They are grouped by their aggressiveness. Less aggressive non-Hodgkin lymphomas are compatible with a long survival while more aggressive non-Hodgkin lymphomas can be rapidly fatal without treatment. Without further narrowing, the label is of limited usefulness for people or doctors. The subtypes of lymphoma are listed there.[citation needed]

Nevertheless, the Working Formulation and the NHL category continue to be used by many. To this day, lymphoma statistics are compiled as Hodgkin's versus non-Hodgkin lymphomas by major cancer agencies, including the US National Cancer Institute in its SEER program, the Canadian Cancer Society and the IARC.

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.00 1.01 1.02 1.03 1.04 1.05 1.06 1.07 1.08 1.09 1.10 1.11 1.12 1.13 1.14 1.15 "Adult Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma Treatment (PDQ®)–Patient Version". NCI. 3 August 2016. Archived from the original on 16 August 2016. Retrieved 13 August 2016.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 "SEER Stat Fact Sheets: Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma". NCI. April 2016. Archived from the original on 6 July 2014. Retrieved 13 August 2016.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 World Cancer Report 2014. World Health Organization. 2014. pp. Chapter 2.4, 2.6. ISBN 978-9283204299.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 GBD 2015 Mortality and Causes of Death Collaborators (8 October 2016). "Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 310 diseases and injuries, 1990–2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015". Lancet. 388 (10053): 1545–1602. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31678-6. PMC 5055577. PMID 27733282.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 GBD 2015 Mortality and Causes of Death Collaborators (8 October 2016). "Global, regional, and national life expectancy, all-cause mortality, and cause-specific mortality for 249 causes of death, 1980–2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015". Lancet. 388 (10053): 1459–1544. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(16)31012-1. PMC 5388903. PMID 27733281.

- ↑ "Adult Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma Treatment (PDQ®)–Health Professional Version". NCI. 1 June 2016. Archived from the original on 12 August 2016. Retrieved 13 August 2016.

- ↑ "Different types of non Hodgkin lymphoma". Cancer Research UK. Archived from the original on 14 August 2016. Retrieved 13 August 2016.

- ↑ Bope, Edward T.; Kellerman, Rick D. (2015). Conn's Current Therapy 2016. Elsevier Health Sciences. p. 878. ISBN 9780323355353. Archived from the original on 10 September 2017.

- ↑ Audebert A (April 2005). "[Women with endometriosis: are they different from others?]". Gynecologie, Obstetrique & Fertilite (in French). 33 (4): 239–46. doi:10.1016/j.gyobfe.2005.03.010. PMID 15894210.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - ↑ Somigliana E, Vigano' P, Parazzini F, Stoppelli S, Giambattista E, Vercellini P (May 2006). "Association between endometriosis and cancer: a comprehensive review and a critical analysis of clinical and epidemiological evidence". Gynecologic Oncology. 101 (2): 331–41. doi:10.1016/j.ygyno.2005.11.033. PMID 16473398.

- ↑ Maeda E, Akahane M, Kiryu S, Kato N, Yoshikawa T, Hayashi N, Aoki S, Minami M, Uozaki H, Fukayama M, Ohtomo K (2009). "Spectrum of Epstein-Barr virus-related diseases: A pictorial review". Japanese Journal of Radiology. 27 (1): 4–19. doi:10.1007/s11604-008-0291-2. PMID 19373526.

- ↑ Peveling-Oberhag J, Arcaini L, Hansmann ML, Zeuzem S (2013). "Hepatitis C-associated B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphomas. Epidemiology, molecular signature and clinical management". Journal of Hepatology. 59 (1): 169–177. doi:10.1016/j.jhep.2013.03.018. PMID 23542089.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 Pinzone MR, Fiorica F, Di Rosa M, Malaguarnera G, Malaguarnera L, Cacopardo B, et al. (October 2012). "Non-AIDS-defining cancers among HIV-infected people". European Review for Medical and Pharmacological Sciences. 16 (10): 1377–88. PMID 23104654.

- ↑ Kramer S, Hikel SM, Adams K, Hinds D, Moon K (2012). "Current Status of the Epidemiologic Evidence Linking Polychlorinated Biphenyls and Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma, and the Role of Immune Dysregulation". Environmental Health Perspectives. 120 (8): 1067–75. doi:10.1289/ehp.1104652. PMC 3440083. PMID 22552995.

- ↑ Zani C, Toninelli G, Filisetti B, Donato F (2013). "Polychlorinated biphenyls and cancer: an epidemiological assessment". J. Environ. Sci. Health C. 31 (2): 99–144. doi:10.1080/10590501.2013.782174. PMID 23672403.

- ↑ Lauby-Secretan B, Loomis D, Grosse Y, El Ghissassi F, Bouvard V, Benbrahim-Tallaa L, Guha N, Baan R, Mattock H, Straif K (2013). "Carcinogenicity of polychlorinated biphenyls and polybrominated biphenyls". Lancet Oncology. 14 (4): 287–288. doi:10.1016/s1470-2045(13)70104-9. PMID 23499544. Archived from the original on 28 August 2021. Retrieved 8 November 2019.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 Tobias J, Hochhauser D (2015). Cancer and its Management (7th ed.). Wiley-Blackwell. ISBN 9781118468715.

- ↑ Arnold S Freedman, Lee M Nadler (2000). "Chapter 130: Non–Hodgkin's Lymphomas". In Kufe DW, Pollock RE, Weichselbaum RR, Bast RC Jr, Gansler TS, Holland JF, Frei E III (eds.). Holland-Frei Cancer Medicine (5th ed.). Hamilton, Ont: B.C. Decker. ISBN 1-55009-113-1. Archived from the original on 10 September 2017.

- ↑ Cerhan JR, Slager SL (November 2015). "Familial predisposition and genetic risk factors for lymphoma". Blood. 126 (20): 2265–73. doi:10.1182/blood-2015-04-537498. PMC 4643002. PMID 26405224.

- ↑ "Revision of the CDC surveillance case definition for acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. Council of State and Territorial Epidemiologists; AIDS Program, Center for Infectious Diseases" (PDF). MMWR Supplements. 36 (1): 1S–15S. August 1987. PMID 3039334. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 June 2017.

- ↑ Lee B, Bower M, Newsom-Davis T, Nelson M (2010). "HIV-related lymphoma". HIV Therapy. 4 (6): 649–659. doi:10.2217/hiv.10.54. ISSN 1758-4310.

- ↑ Ansell, Stephen M. (August 2015). "Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma: Diagnosis and Treatment". Mayo Clinic Proceedings. 90 (8): 1152–1163. doi:10.1016/j.mayocp.2015.04.025. ISSN 1942-5546. Archived from the original on 28 August 2021. Retrieved 26 April 2021.

- ↑ "Non-Hodgkin lymphoma". Cancer Council Australia. 22 March 2019. Archived from the original on 23 August 2019. Retrieved 23 August 2019.

- ↑ "Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma Treatment". American Cancer Society. 2019. Archived from the original on 23 August 2019. Retrieved 23 August 2019.

- ↑ "Immunotherapy for Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma". American Cancer Society. 2019. Archived from the original on 23 August 2019. Retrieved 23 August 2019.

- ↑ "Treating B-Cell Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma". American Cancer Society. 2019. Archived from the original on 28 June 2019. Retrieved 23 August 2019.

- ↑ Fisher SA, Cutler A, Doree C, Brunskill SJ, Stanworth SJ, Navarrete C, Girdlestone J, et al. (Cochrane Haematological Malignancies Group) (January 2019). "Mesenchymal stromal cells as treatment or prophylaxis for acute or chronic graft-versus-host disease in haematopoietic stem cell transplant (HSCT) recipients with a haematological condition". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 1: CD009768. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD009768.pub2. PMID 30697701. Archived from the original on 27 August 2021. Retrieved 8 July 2020.

- ↑ "Non-Hodgkin's Lymphoma Diagnosis, Treatment, Symptoms & Causes". MedicineNet. Archived from the original on 6 June 2020. Retrieved 27 May 2020.

- ↑ Lozano R, Naghavi M, Foreman K, Lim S, Shibuya K, Aboyans V, Abraham J, Adair T, Aggarwal R, Ahn SY, et al. (15 December 2012). "Global and regional mortality from 235 causes of death for 20 age groups in 1990 and 2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010". Lancet. 380 (9859): 2095–128. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61728-0. hdl:10536/DRO/DU:30050819. PMID 23245604.

- ↑ Patte, Catherine; Bleyer, Archie; Cairo, Mitchell S. (2007). "Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma". In Bleyer, W. Archie; Barr, Ronald D. (eds.). Cancer in Adolescents and Young Adults (Pediatric Oncology). Springer. p. 129. doi:10.1007/978-3-540-68152-6_9. ISBN 978-3-540-40842-0.

- ↑ "Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma Overview". lymphoma.org.au. 2019. Archived from the original on 24 August 2019. Retrieved 24 August 2019.

- ↑ "Canadian Cancer Statistics". www.cancer.ca. Archived from the original on 25 January 2018. Retrieved 8 February 2018.

- ↑ "Non-hodgkin lymphoma statistics". Cancer Research UK. 14 May 2015. Archived from the original on 7 October 2014. Retrieved 24 August 2019.

- ↑ "Cancer Stat Facts: Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma". National Cancer Institute: Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) Program. Archived from the original on 1 April 2019. Retrieved 24 August 2019.

- ↑ "Key Statistics for Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma". www.cancer.org. Archived from the original on 24 August 2019. Retrieved 24 August 2019.

External links[edit | edit source]

- Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma Archived 27 June 2010 at the Wayback Machine at American Cancer Society

- Non-Hodgkins Lymphoma Archived 24 February 2012 at the Wayback Machine from Cancer.net (American Society of Clinical Oncology)

- Patient information on non-Hodgkin lymphoma Archived 31 August 2019 at the Wayback Machine from The Lymphoma Association

- Lymphoma Association – Specialist UK charity providing free information and support to patients, their families, friends and carers Archived 24 February 2018 at the Wayback Machine

| Classification | |

|---|---|

| External resources |

Categories: [Non-Hodgkin lymphoma] [Hepatitis C virus-associated diseases] [Lymphoma] [RTT]

↧ Download as ZWI file | Last modified: 01/12/2024 12:06:55 | 3 views

☰ Source: https://mdwiki.org/wiki/Non-Hodgkin_lymphoma | License: CC BY-SA 3.0

ZWI signed:

ZWI signed:.jpg)

.jpg)

KSF

KSF