Mccarthyism

From Conservapedia

From Conservapedia The word McCarthyism according to journalist Phil Brennan "was coined in the bowels of NKVD headquarters at 3 Dzerzhinsky Square in Moscow and first published in the Communist Daily Worker, Moscow’s U.S. house organ with the justified belief that it would be enthusiastically picked up and used by America’s useful liberal idiots." [1]

It is a derogatory and misleading term, based on false premises. First, Senator McCarthy had nothing to do with the House Un-American Activities Committee or the Hollywood Blacklist. Second, and more important, it was not true that all McCarthy called to testify were innocent or that liberals were merely defending civil liberties.

Americans and conservatives were deeply concerned about the loss of China, the world's largest populated state, to totalitarian communists through subversion and overt aid of liberal New Dealers and communists in the Deep State, and the impact such a catastrophe would have on future generations.

The Venona intercepts revealed that McCarthy was right about the true extent of Soviet spies in the U.S. government, the danger they presented to national security, and subversion of U.S. national interests.

Contents

- 1 Pretext

- 2 Western betrayal

- 3 Amerasia cover up

- 4 The Silvermaster case

- 5 Failure to discharge security risks

- 6 Hiss and the UN

- 7 White and the IMF

- 8 Oppenheimer and atomic espionage

- 9 China and subversion of the Four Policeman

- 10 Korea and the nuclear arms race

- 11 Extrajudicial means

- 12 Tensions of the times

- 13 More spy cases

- 14 Hiss convicted and the vendetta against Nixon

- 15 A housewife electrocuted and Oppenheimer walks

- 16 Hypocrisy regarding McCarthy's methods

- 17 The New Left

- 18 See also

- 19 Further reading

- 20 References

- 21 External links

Pretext[edit]

Senator Joseph McCarthy led a prominent public campaign to investigate Communist Party members working in sensitive US government jobs who were in violation of the Hatch Act prohibiting federal employment of workers with membership in "any political organization which advocates the overthrow of our constitutional form of government." By 1950, it was widely known that the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics had obtained atomic weapons know-how with the assistance of American citizens, many of them government employees. The United States had spent $4 billion to develop the technology, roughly equivalent to $80 billion today. The international situation was extremely tense at the time, and public knowledge that America's Cold War enemy obtained nuclear weapons capability with the help of federal government employees, along with the perception that the Truman administration was unconcerned about it, was very worrisome to many.

McCarthy's efforts to remove security risks from government employment infuriated the American Left, and they often use the term to mean aggressive questioning of someone's background or personal beliefs, or making accusations of disloyalty. It is meant as a derogatory term, and sometimes used to refer to House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC) or the Hollywood Blacklist, even though those weren't really part of McCarthy's campaign.[3]

Western betrayal[edit]

- Main article: Western betrayal

Amerasia cover up[edit]

On June 6, 1945, less than a month after the War in Europe ended and while the pacific War was winding down, 6 persons, including three U.S. government officials, were arrested on conspiracy and espionage charges related to possession of roughly 1000 stolen classified Government documents in the offices of Amerasia magazine. Amerasia had published classified materials verbatim from the United States wartime intelligence service, the Office of Strategic Services (OSS). FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover believed he had an "airtight case," and Justice Department officials were ready to prosecute. Thomas Corcoran (Tommy the Cork), a former Franklin Roosevelt personal adviser who lived in the White House at the President's side and afterward became a prominent Washington lawyer and fixer, worked with the Truman administration to cover up the case. Soviet agent Duncan Lee, who served as counsel to OSS chief General William Donovan and was the highest ranking KGB operative among nearly two dozen Soviet agents who penetrated the OSS, after the War was working in Corcoran's Washington law firm.[4]

A transmission from Soviet Military Intelligence (GRU) agents in New York on June 16, 1943 to Moscow read,

Joseph Bernstein has established friendly relations with T.A. Bisson . . who has recently left BEW; he is now working in the Institute of Pacific Relations (IPR) and in the editorial offices of Bernsteins’ periodical Amerasia. . . Bisson passed to Bernstein . . . copies of four documents:

(a) his own report for BEW with his views on working out a plan for shipment of American troops to China;

(b) a report by the Chinese embassy in Washington to its government in China. . . .

(c) a brief BEW report of April 1943 on a general evaluation of the forces of the sides on the Soviet-German front. . . .

(d) a report by the American consul in Vladivostok. . ." [5]

Joseph Bernstein to whom Bisson gave this material is the same Moscow agent who was a contact of Philip Jaffe in the 1940s. Thus Bisson not only promoted the cause of the CCP, as Sen. McCarthy alleged, but also passed confidential data to the GRU. McCarthy made accusations against Bisson, and had certain evidence to prove it. But McCarthy was unaware of the extent of Bisson's complicity. The truth was unknown for 50 years.[6]

The Silvermaster case[edit]

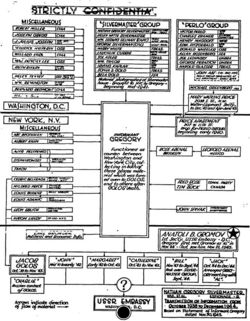

In November 1945 when the War was finally over, a courier from a very large CPUSA underground apparatus operating in numerous federal agencies throughout the New Deal,which included the White House, defected to the FBI. The KGB had removed Elizabeth Bentley from overseeing at least 80 KGB sources late in the war. When she realized she knew too much, was no longer of use to the KGB and her life was in danger, she told her story in a deposition to the FBI. Bentley was assigned covername "Gregory" to protect her identity, and the highly secret investigation was referred to as "the Gregory Case."

The FBI knew of 5 Soviet agents during the war, Bentley added at least another 80, some of them still employed in the government at that time. Her story at first was incredible, even embarrassing to the FBI, but it soon was determined that Bentley's allegations were borne out by information already in Bureau files.[9] By December, no fewer than 227 FBI agents were investigating in the case.[10]

For much of 1946 the suspects were surveilled, other information came from Igor Guzenko,[11] a Soviet code clerk who defected in Canada. The FBI was unaware at this point the Army Signals Intelligence Service was secretly reading KGB communications with Moscow. In the later part of February a 194-page report based upon Bentley's deposition entitled, Underground Espionage Organization (NKVD) in Agencies of the United States Government [12] was transmitted to Secretary of State George Marshall an other agencies. By December 1946 leaks were developing.[13]

In January 1947, Edward Morgan of the FBI was asked to make an objective analysis of the case.[14] Morgan writes, "Coming in after the event as the Bureau did, we are now on the outside looking in, with the rather embarrassing responsibility of having a most serious case of Soviet espionage laid in our laps without a decent opportunity to make it stick. This very circumstance, however, necessitates pursuing more direct methods." Not knowing of the super secret Venona project yet, Morgan observes, "the case is no more than the word of [Bentley] against that of the several conspirators. The likely result would be an acquittal under very embarrassing circumstances." Morgan suggests it is possible “some of the lesser lights among the subjects would crack during the course of a careful and pointed interview" and concludes with the recommendation "That one of the subjects of this case, probably the weakest sister, be contacted with a view to making him an informant...Failing in this respect, that immediately the other subjects be exhaustively interviewed. Since an interview with one would virtually amount to putting all of them on notice, it would seem logical to conduct such interviews as nearly simultaneously as possible....That failing to break any of the subjects, serious consideration be given to exposing this lousy outfit and at least hounding them from the Federal Service. Several possibilities exist in this regard but this would seem to be a bridge to cross when we get to it."

Press leaks continued from an Executive Conference formed of DOJ prosecutors and FBI investigators discussing how to proceed. In a hand written margin note from a memo dated January 23, 1947, Hoover writes, "in view of all the 'gabbing' done by the Dept to the Press there is little which can be expected from any action now." [15] Four days later Hoover, in a somber tone, recommends to the Attorney General, "I am of the opinion...it will be impossible to continue the investigation....the subjects...are now all very security conscious... any attempt to interrogate them, either by Bureau agents or before a grand jury, would produce nothing. Obviously, this situation leaves only the third alternative; that is, that the Department furnish to the employing departments the basic data concerning the activities of the individual subjects as a possible means of concluding the case. It is assumed, of course, that the employing departments will take administrative action against the subjects who are employed in these departments." [16]

Failure to discharge security risks[edit]

In June 1947, members of the Senate Appropriations Committee sent a confidential report to Secretary of State George Marshall, in which they stated:

| “ | It is evident that there is a deliberate calculated program being carried out not only to protect Communist personnel in high places, but to reduce security and intelligence protection to a nullity. . . . On file in the Department is a copy of a preliminary report of the FBI on Soviet espionage activities in the United States, which involves large numbers of State Department employees. . . this report has been challenged and ignored by those charged with the responsibility of administering the department... | ” |

The memorandum listed the names of nine State Department officials and said that they were "only a few of the hundreds now employed in varying capacities who are protected and allowed to remain despite the fact that their presence is an obvious hazard to national security." On June 24, 1947, Assistant Secretary of State John Peurifoy notified the chairman of the Senate subcommittee that ten persons had been dismissed from the department, five of whom had been listed in the memorandum. But from June 1947 until McCarthy's Wheeling speech in February 1950, the State Department did not fire one person as a loyalty or security risk.[17]

In 1947,[18] it was apparent that no individual in the U.S. Government realized that evidence of massive Soviet espionage within the government was developing on twin tracks.[19] There was an FBI counterintelligence investigation [20] which empanelled a grand jury in New York to look into defector Elizabeth Bentley's allegations, and the Army Signal Intelligence Service reading Soviet cipher decrypts [21] at Arlington Hall. It was a case of one hand not knowing what the other was doing. Leaks in the investigation into the Silvermaster case began to threaten the successful prosecution.[22] So when McCarthy later made charges that the Truman administration knowingly protected Soviet agents, on the surface, this appeared to large sectors [23] of the American public[24] as true.

FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover was among only a handful of people in the U.S. Government who was aware of the Venona project, and there is no indication Hoover shared Venona information with McCarthy. In fact, Hoover may have actually fed McCarthy dead end files on family relatives or close associates of real espionage suspects. Hoover told a House Committee in 3 days before McCarthy's Wheeling speech that counterespionage required "an objective different from the handling of criminal cases. It is more important to ascertain his contacts, his objectives, his sources of information and his methods of communication" as "arrest and public disclosure are steps to be taken only as a matter of last resort." He concluded that "we can be secure only when we have a full knowledge of the operations of an espionage network, because then we are in a position to render their efforts ineffective." [25] And there is no indication McCarthy might have known he was being used by Hoover in this way.

One day before McCarthy's Wheeling speech the Chairman of the Joint Atomic Energy Intelligence Committee (JAEIC) wrote a memorandum to the Scientific Intelligence Committee complaining how they had been kept out of the intelligence sharing loop after the confession of Klaus Fuchs became more widely known. In the memorandum the JAEIC suspected the FBI and others may have counter espionage information of considerable value in making an estimate on the status of the Soviet atomic. In the summer of 1949 the FBI learned that the secret of the construction of the atom bomb had been stolen and turned over to a foreign power. An immediate investigation resulted in the identification of Fuchs.[26] The JAEIC stated had they known in June about Fuchs, it would have impacted their estimate of Soviet atomic capabilities released in July which did not foresee the Soviet Union exploding its first nuclear device at the end of August in 1949. They noted some information was obtained through HUAC, some from Canada as a result of the Igor Gouzenko case, and Hoover supplied some information but it was only of slight value. The memorandum declares, "The only real assurance we have of getting the information at present seems to be as a result of a Congressional Committee" or the arrest of suspects.[27]

In summary memorandums to Director Hoover of Venona project information begun in 1950 entitled, Operations of the MGB Residency at New York, 1944-45, Special Agent Alan Belmont reported the FBI had identified 206 persons involved in Soviet espionage activity who had been active in United States. Of this number the FBI had information from defector Elizabeth Bentley and other sources regarding espionage activity on 87 of these persons. Espionage activity on the part of 119 persons from Venona information were not known to the FBI prior to 1946 but many were identified through investigation by 1950.[28]

Hiss and the UN[edit]

When the Office of Special Political Affairs (OSPA) was created in 1944, Alger Hiss became the deputy director - a sensitive and key position. In August 1944, Hiss was executive secretary of the Dumbarton Oaks conference. When he returned to Washington, all matters pertaining to the United Nations organization came under his direct supervision. With Harry Hopkins, Cordell Hull, and others, Hiss worked on the first drafts of the UN Charter.[29] Hiss negotiated privately with the ailing U.S. president, Franklin Roosevelt, and CPSU General Secretary Josef Stalin at the Yalta conference.[30] It was here that FDR agreed to allow the Soviet Union to occupy Poland and set up a Comintern affiliated puppet state—a clear violation of the principles of self-determination expressed in the Atlantic Charter, and the very cause over which Great Britain went to war with Germany in September 1939. What's more, it was the betrayal of an ally – the Polish Government – which had signed the Atlantic Charter and the United Nations Declaration.

On March 3, 1945, the director of the KGB, Lt. General Pavel Fitin instructed Ishkak Akhmerov, head of KGB Illegal operations in the United States to learn what he could about American plans for the forthcoming United Nations San Francisco Conference. Assigning top priority to the task, Fitin ordered an early report. Hiss was responsible for planning the conference. Hiss had been working with Soviet Military Intelligence (GRU), since the mid 1930s. Ordinarily security procedures dictated that a Case officer from one Soviet Intelligence organization would not contact an agent working for another, however under the extraordinary circumstances of the approaching UN organizational conference late in the war, Akhmerov did so, and reported on his contact with Hiss.[31][32][33] Akhmerov reported how after the Yalta conference Hiss traveled to Moscow where Andrey Vyshinsky passed on to him the GRU's gratitude.[34] A codename was assigned by one Soviet Intelligence agency for an agent working for another Soviet Intelligence agency which created confusion among investigators.[35][36] A Senate Internal Security Subcommittee investigation determined that Hiss was responsible for the employment of 494 persons on the United Nations initial staff.[37] With the leaks in the Silvermaster case, Elizabeth Bentley was called to testify in late July 1948, and Whittaker Chambers, a CPUSA defector from the 1930s, a few days later repeated information he had given to President Franklin Roosevelt's Assistant Secretary of State Adolf Berle in 1939 - firsthand knowledge of Hiss's espionage activity - information that Berle in person relayed to President Roosevelt.[38][39][40] Ambassador to the Soviet Union William Bullitt had likewise warned FDR as early as 1939 that Hiss was an agent of the Soviet Union.[41]

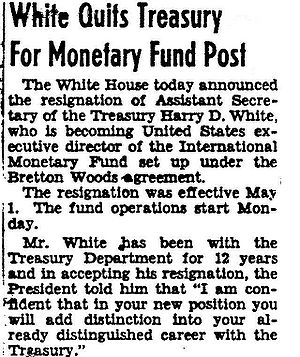

White and the IMF[edit]

In May 1941 Assistant Secretary of the Treasury Harry Dexter White met for lunch with Vitali Pavlov, KGB assistant to the Chief of Military Section for work in the United States and Canada. White had been carefully selected by Iskhak Akhmerov, who ran the Silvermaster group and knew White. The purpose was to present a series of policy initiatives for White to inject into Washington's foreign policy discussion which involved Soviet efforts to provoke tensions in U.S. Japanese relations. The strategy was to encourage Japan's war party to view the United States as Japan's main enemy, rather than Soviet Union after several recent clashes on the Manchukuo border and Comintern support to the Maoist CCP. Pavlov handed White an outline of themes to promote among key U.S. policymakers including a demand, to be wrapped in tough rhetoric, that Japan recall its armed forces from China.[42][43] The Soviet Union had occupied Xinjiang (Sinkiang) since 1934.[44]

President Roosevelt accepted White's proposals for economic sanctions against Japan and on July 26, 1941 implemented a full scale economic blockade, froze all Japanese financial assets in the U.S. which virtually ended all trade between the two countries. The chief of the Japanese Navy told the emperor that if Japan resorted to war, it would be doubtful Japan could win. The Japanese Cabinet sought desperately to reach an agreement in Washington.[45] Japan abandoned all military plans against Soviet Siberia, which had badly needed Red Army troops at that moment for the defense of Moscow pinned down, and looked to the south instead for the oil resources. Due to White's involvement and influence, the administration set up a foreign policy that placed Soviet interests ahead of the United States.[46] In August, 1941, Japanese Prime Minister Konoe made a proposal to meet with President Roosevelt. On November 18, 1941, Secretary of the Treasury Henry Morgenthau sent to Secretary of State Hull a memorandum drafted by White on the terms for peace that should be presented to Japan.[47] At noon on November 25, Secretary of War Henry Stimson and Secretary of the Navy Frank Knox met at the White House with General George C. Marshall. Stimson wrote in his diary the main question was "how we should maneuver them into the position of firing the first shot without allowing too much danger to ourselves. It was a difficult proposition." [48] In his testimony before the Congressional Committee investigating the attack on Pearl Harbor, General Marshall said that if the 90-day truce which was the substance of the Kanoe-Roosevelt proposal had been effected, the United States might never have become involved in the World War II at all; that a delay by the Japanese from December, 1941 into January, 1942 might have resulted in a change of Japanese opinion as to the wisdom of the attack because of the collapse of the German front before Moscow in December, 1941.[49] On the afternoon of November 26, 1941, Hull put in final shape the ultimatum. In this ten-point ultimatum, eight of the drastic demands were written by Harry Dexter White, an agent of the Soviet Union. The harsh, demanding language only strengthened the position of the war party in Tokyo and Nomura found it impossible to reach an agreement because White's demands were extreme.[50] War between the United States and Japan - the lone obstacle to Comintern designs in the Far East - was the primary aim of Soviet foreign policy in the Far East.

On November 8, 1945 the FBI notified the White House with a provisional summary of defector Elizabeth Bentley's revelations.[51] President Truman, whose motto was "The Buck Stops Here," telephoned FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover on November 14 and told Hoover to confer with Secretary of State James Byrnes on the various matters of Soviet espionage.[52] On May 4, 1946 Truman announced the appointment of White to head the newly created International Monetary Fund. White, like Greg Silvermaster and others, rather than be fired as a Security risk at a time when there was public support for the execution of spies, received a transfer, promotion and increase in pay grade.

Oppenheimer and atomic espionage[edit]

An 86 year old Pavel Sudoplatov wrote in his memoirs,

| “ | My Administration for Special Tasks was responsible for sabotage, kidnapping, and assassination of our enemies beyond the country's borders. It was a special department working in the Soviet security service....I was also in charge [53] of the Soviet espionage effort to obtain the secrets of the atomic bomb from America and Great Britain. I set up a network of illegals [54] who convinced Robert Oppenheimer,[55] Enrico Fermi, Leo Szilard, Bruno Pontecorvo, Alan Nunn May, Klaus Fuchs, and other scientists in America and Great Britain to share atomic secrets with us.[56] | ” |

| “ | The most vital information for developing the first Soviet atomic bomb came from scientists designing the American atomic bomb at Los Alamos, New Mexico...Oppenheimer, Fermi, Szilard, and Szilard's secretary were often quoted in the NKVD files from 1942 to 1945 as sources for information on the development of the first American atomic bomb. It is in the record that on several occasions they agreed to share information on nuclear weapons with Soviet scientists. At first they were motivated by fear of Hitler; they believed that the Germans might produce the first atomic bomb. Then the Danish physicist Niels Bohr helped strengthen their own inclinations to share nuclear secrets with the world academic community. By sharing their knowledge with the Soviet Union, the chance of beating the Germans to the bomb would be increased.[57] | ” |

| “ | Gregory Kheifetz, our operative who had been successful in atomic espionage...described Oppenheimer as a man who thought of problems on a global scale. Oppenheimer saw the threat and promise of the atomic age and understood the ramifications for both military and peaceful applications. We always stressed that contacts with him should be carefully planned to maintain security, and should not be used for acquiring routine information.[58] We knew that Oppenheimer would remain an influential person in America after the war [59] and therefore our relations with him should not take the form of running a controlled agent. We understood that he and other members of the scientific community were best approached as friends, not as agents. Since Oppenheimer, Bohr, and Fermi were fierce opponents of violence, they would seek to prevent a nuclear war, creating a balance of power through sharing the secrets of atomic energy. This would be a crucial factor in establishing the new world order after the war, and we took advantage of this.[60] | ” |

| “ | In developing Oppenheimer as a source, Vassili Zarubin's wife, Elizabeth, was essential. ...In 1941 Elizabeth Zarubina was a captain in the KGB. After her husband's posting to Washington, she traveled to California frequently to cultivate the Oppenheimer family through social contacts arranged by Kheifets. Kheifets then introduced Elizabeth to Oppenheimer's wife, Katherine, who was sympathetic to the Soviet Union and Communist ideals, and the two worked out a system for future meetings." [61] | ” |

| “ | By 1943 it was agreed at the Center that all contacts with Oppenheimer would be through illegals only. Lev Vasilevsky, our rezident in Mexico City, was put in charge of running the illegal network after Zarubin left. But Vasilevsky was directed to control the network from Mexico City, not to move to Washington, where the FBI could more easily monitor our activities. Our facilities in Washington were to be used as little as possible. ...Vasilevsky told me that on one occasion in 1944 he visited Washington in order to pass to the Center materials received from Fermi. To his dismay, the embassy radio operator, who was supposed to encode his message, was missing. The next day the clerk was brought to the embassy by the American police, who had picked him up dead drunk in a nearby bar. Vasilevsky decided on the spot not to use the Washington embassy to transmit any of his sensitive messages; he would rely on Mexico City. ...In 1945, for his work in handling the Fermi line in the United States, Vasilevsky was appointed deputy director of Department S. For a short period in 1947 he was the director of the department of scientific and technological intelligence in the Committee of Information, which was the central intelligence-gathering agency from 1947 to 1951.[62] | ” |

| “ | A description of the design of the first atomic bomb was reported to us in January 1945. In February, although there was still uncertainty in the report, our rezidentura in America stated that it would take a minimum of one year and a maximum of five years to make a sizable bomb.[63]....We decided that Terletsky should be sent to see Bohr .... He was to explain the problems in activating the nuclear reactor to Bohr and to seek his advice. Terletsky could not be sent alone on such a critical assignment, so he was accompanied by Lev Vasilevsky, who had run the Fermi line from Mexico and now was my deputy director of Department S. He would lead the conversation with Bohr while Terletsky would handle the technical details..... Bohr understood, perhaps for the first time, that the decision that he, Fermi, Oppenheimer, and Szilard had made to allow their trusted scientific proteges to share atomic secrets had led him to meet agents of the Soviet government.... Bohr readily explained to Terletsky the problems Fermi had at the University of Chicago putting the first nuclear reactor into operation, and he made valuable suggestions that enabled us to overcome our failures. Bohr pointed to a place on a drawing Terletsky showed him and said, "That's the trouble spot." This meeting was essential to starting the Soviet reactor, and we accomplished that feat in December 1946.[64] | ” |

China and subversion of the Four Policeman[edit]

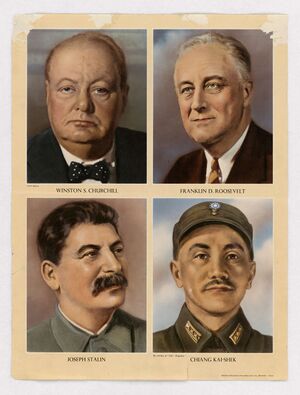

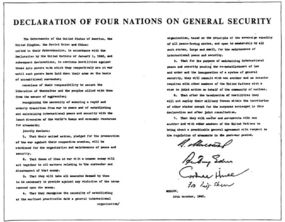

On January 1, 1942, the Soviet and Chinese Nationalist ambassadors in Washington joined with President Franklin Roosevelt and British Prime Minister Winston Churchill in signing the Declaration by United Nations. Twenty-two other nations added their signatures creating the wartime alliance. The Atlantic Charter was hailed as "a common program of purposes." FDR apparently himself thought up the name "United Nations."

The order in which the declaration was signed, first by the four major powers and then the other nations, reflected FDR's belief in the moral concept of "trusteeship of the powerful" for the well-being of the less powerful. The central proposal was the prompt creation of the United Nations Authority composed of all the signers in FDR's "Great Design",[65] led by the United States, Great Britain, the Soviet Union, and Nationalist China. The President privately referred to these four major powers as the Four Policemen.[66] In October 1943 at the Moscow Conference the governments of the United States, United Kingdom, the Soviet Union and the Kuomintang committed themselves to "the necessity of establishing at the earliest practicable date a general international organisation...after the termination of hostilities they will not employ their military forces within the territories of other states except for the purposes envisaged in this declaration and after joint consultation... they will confer and co-operate with one another and with other members of the United Nations to bring about a practicable general agreement with respect to the regulation of armaments in the post-war period. " [67]

Edgar Snow introduced Mao and Zhou Enlai to American readers in 1937 in his book, Red Star Over China, shortly after the Chinese Red Army’s route by Chiang Kai-shek in 1934 and their year long retreat to Yenan known as the Long March. Snow wrote, "the political ideology, tactical line and theoretical leadership of the Chinese Communists have been under the close guidance, if not positive detailed direction, of the Communist International, which during the last decade has become virtually a bureau of the Russian Communist Party." And he further declared that the CCP had to subordinate itself to the "strategic requirements of Soviet Russia, under the leadership of Stalin."[68]

KGB Agent and presidential adviser Lauchlin Currie secured for Comintern operative Owen Lattimore the appointment by Roosevelt as the American adviser for the Kuomintang and Generalissimo Chiang Kai-shek.[69] During the Communazi period, the FBI issued a notice that Lattimore should be considered for custodial detention in the event of a national emergency.[70]

On November 25, 1941 Lattimore sent a dispatch from China to Currie in the White House arguing against a proposed diplomatic understanding between the United States and Japan. Currie's assistant in the White House, Michael Greenberg, was another Soviet operative and part of the Silvermaster group.[71] Secretary of State Cordell Hull testified later he took a tough line with the Japanese because of the cable from Lattimore to Currie reporting on Chinese morale in the Kuomintang. The cable from Lattimore to Currie was the only documentary evidence Hull presented which influenced his decision to reverse himself and send the harsh ultimatum written by KGB Agent Harry Dexter White to Japan after Congress investigated the Pearl Harbor attack.[72] Prof. Anthony Kubek has written that Lattimore, by this one act, designed to accomplish the Soviet objective of promoting war between the United States and Japan—did more to promote the Sovietization of China than in any other act of Lattimore's career. All Comintern designs for conquest of China hinged upon destroying Japan and the balance of power in the Pacific.[73]

Defector Louis Budenz testified that Lattimore had been hand picked by the Comintern "to change the thinking here in Washington and in America on the Communist activities in China and relations to the Soviet Union." Lattimore was thought to be a man "who could put out propaganda and conceal the Communist activity, but still have it carry out the policy of the Communists." According to Budenz "the weight of his discussions was always along the lines of the Soviet policy," but the language employed 'Was non-Soviet in character.' " [74] When, on June 15, 1943, Lattimore instructed Joseph Barnes[75] to replace the non-Communist Chinese of the U.S. Office of War Information (OWI) with Communists, OWI did so. On July 14 Thomas A. Bisson, in the Institute of Pacific Relations (IPR) publication, Far Eastern Survey, referred to Maoist forces as the "democratic China." The disinformation was widely repeated among journalists and academics. Lattimore, Frederick Field and others, were later to write in the New York Times of China's "agrarian reformers." But in July and August 1943, the Maoists—in the midst of the war—joined with the Japanese armies to inflict a serious defeat on Kuomintang troops allied with the United States.[76]

In the second half of 1944, the IPR published a fifty-six-page pamphlet, Our Job in Asia, which was allegedly written by Vice President Henry Wallace after his official 3-month trip to Siberia, China, and Mongolia.[77] "The Russians," the author of the pamphlet claimed, "have demonstrated their friendly attitude toward China by their willingness to refrain from intervening in China's internal affairs." [78][79] The Senate Committee on the Judiciary was to find that in 1944 the IPR, "disseminated and sought to popularize false information including information originating from Soviet and Communist sources." [80] Some years later Wallace admitted in testimony that most of a book entitled Soviet Asia Mission supposedly written by him detailing his official Far Eastern trip actually had been written by Andrew J. Steiger, a person identified under oath as a Communist party member. The Communist party advocated the violent overthrow of the United States Government and was an agency of a foreign government.[81] To Joseph Fels Barnes, Owen Lattimore, and Harriet Lucy Moore, all identified under oath as Communist party members, the Vice President expressed his gratitude for their "invaluable assistance in preparing the manuscript." [82]

Chiang Kai-shek himself claimed that Harry Dexter White and his staff sabotaged his government's economic policies. The U.S. government made a commitment to Chiang in writing to supply $200 million in gold to Nationalist China [83] in 1943 to stabilize the Chinese currency at a time when inflation was spiraling out of control.[84] White's policy prevented the shipment until it was too late to be effective in stemming inflation. In a December 9, 1944 memo to Treasury Secretary Morgenthau, White wrote,

| “ | We have stalled as much as we have dared and have succeeded in limiting gold shipments to $26 million during the past year. We think it would be a serious mistake to permit further large shipments at this time.[85] | ” |

In July 1945 U.S. War Department memorandum entitled, The Chinese Communist Movement, gave a depiction of the true nature of the CCP, reporting the Maoists allowed no opposition groups in the areas they controlled and were part of the international Comintern movement of violent revolution.[86] Chiang believed that the Truman Doctrine of containing of Moscow directed subversion would extend to China, and ordered an offensive when he heard of the new policy.[87] Truman however, made no effort to save China from enslavement. U.S. Secretary of State George Marshall himself testified that such aid might have worked, but General David Barr's military mission was specifically instructed not to supply this kind of assistance.[88] General Albert C. Wedemeyer recommended this approach in his report on his 1947 fact-finding mission, but Marshall personally suppressed the report.[89] In the summer of 1946, Truman told Chiang to be more willing to compromise. Chiang replied that first the Communists must abandon "their policy to seize political power through the use of armed force, to overthrow the government and to install a totalitarian regime such as those with which Eastern Europe is now being engulfed." [90]

Secretary of State Dean Acheson, no friend of Joseph McCarthy, admitted on January 12, 1950, in a National Press Club address,

| “ | What is happening in China is that the Soviet Union is detaching the northern provinces of China from China and is attaching them to the Soviet Union. This process is complete in Outer Mongolia. It is nearly complete in Manchuria and I am sure that in Inner Mongolia and Sinkiang there are very happy reports coming from Soviet agents to Moscow."[91] | ” |

Senator McCarthy repeatedly criticized IPR and its former chairman Philip Jessup, observing that Frederick Field, T.A. Bisson, and Lattimore were very active in IPR and worked to turn American China policy in favor of the CCP. John Carter Vincent, John Stewart Service, Alger Hiss, and John Paton Davies all had links to IPR. Jessup in 1949 was the principal editor of the State Department "white paper" on China that abandoned Chiang Kai-chek and the Kuomintang.

The Senate Internal Security Subcommittee (SISS) looked extensively into the problem of unauthorized, uncontrolled and often dangerous power exercised by non-elected officials, specifically Harry Dexter White. Part of its report looked into the implementation of Roosevelt administration policy in China and was published as the Morgenthau Diary.[92]

The report stated in 1967,

| “ | The concentration of Communist sympathizers in the Treasury Department, and particularly the Division of Monetary Research, is now a matter of record. White was the first director of that division; those who succeeded him in the directorship were Frank Coe and Harold Glasser. Also attached to the Division of Monetary Research were William Ludwig Ullman, Irving Kaplan, and Victor Perlo. White, Coe, Glasser, Kaplan, and Perlo were all identified as participants in the Communist conspiracy…." [94] | ” |

During the hearings, 46 persons connected with the IPR were identified as Communist Party members.[95][96] In the final report the SISS noted:

- "The IPR has been considered by the American Communist Party and by Soviet officials as an instrument of Communist policy, propaganda and military intelligence. The IPR disseminated and sought to popularize false information including information originating from Soviet and Communist sources. . . . The IPR was a vehicle used by the Communists to orientate American far eastern policies toward Communist objectives. . ." [97]

Korea and the nuclear arms race[edit]

On Sunday morning, June 25, 1950, Communist armies of North Korea crossed the border in an invasion of the southern republic. Two days later President Truman announced: "I have ordered the United States air and sea forces to give the Korean government troops, cover and support." The next day American ground and air forces were fully engaged in South Korea in what the President called "a police action." John T. Flynn described the perplexity of the American electorate: "Thus [the U.S] became enmeshed in an obscure tangle of circumstances... involving objectives so dimly seen, stretching on to problems so insoluble, and promising stresses on our economic and political system ... in pursuit of ends no one understands and involving costs and consequences we cannot measure."[98] The Korean War disrupted the postwar economic boom with military service, shortages, restrictions and cost-of-living inflation which could not help but breed discontent. And through it all, Prof. Carroll Quigley points out, "the press kept up a constant barrage of 'Communists in Washington,' 'twenty years of treason.'"[99]

Chiang Kai-shek was caught between two wars—a war on China by Japan and a war on China by the Soviet Union. American leaders refused to see this and insisted on acting in the illusion that China was fighting the Japanese only and that Soviet Union was an ally. Then came the startling realization that the United States, too, like China, was engaged in two wars in Asia, one against a common enemy, Japan; the other against a common enemy, the Soviet Union. The United States, with its ally China, fought the Japanese. But all the time the Soviet Union, with its satellite Comintern army in China, was fighting both China and the United States. The iron curtain that, with the Yalta agreement, was rung down over American allies in Europe—Poland and Czechoslovakia and other little countries—fell on China also. And this was made possible wholly because of the Soviet Union's allies—conscious and unconscious—in America, in the U.S. government and even in the U.S. State Department.

Extrajudicial means[edit]

Defector Louis Budenz stated publicly he could identify 400 members of the Communist conspiracy which had delivered the know-how to build the atomic bomb to the Soviet Union. This number of 400 was closely corroborated by the 349 codenames the cryptographers in the Venona project discovered and FBI field investigators sought to identify. Defector Elizabeth Bentley also identified 81 persons involved in espionage, and Soviet cipher clerk Igor Gouzenko yielded valuable information when he defected in Canada.

In sum, some 205 total true identities of persons involved in espionage during World War II were known to the FBI by 1950, some being corroborated by multiple sources. Given the secret nature of Venona, and the unwillingness to let the Soviet Union know the US was reading its codes, the known spies were eased out of government positions, and where prosecution could occur using sources other than Venona, a few cases were attempted. But the priority was always to maintain the secrecy regarding the breaking of Soviet codes, remove security risks, and forego law enforcement while cryptographers and field investigators continued working to identify others.

So secret was Venona, that not even President Truman was informed. The revelation Truman had never been informed was the subject of much controversy and discussion when the Venona documents were declassified in 1995. Given the extent of the Soviet penetration of the U.S. Government, including virtually all the U.S. security and intelligence services, the State and Treasury Departments, and even the White House, the decision not to inform Truman appears to have been the logical and appropriate decision.[100] General Omar Bradley took it upon himself not to inform Truman, and told the few others with the knowledge of the Soviet attack on American security that he would inform the President if the need were to arise.[101]

After the Soviet Union exploded its first nuclear test, and it became apparent to the public that the Soviet Union obtained the knowhow from American citizens employed by the federal government during the New Deal, with the growing tensions of the times over the Berlin Airlift, the loss of the U.S.'s wartime ally in China to the Chinese Comintern forces, and later the Korean War, those with knowledge of Venona had as an immediate priority to remove Soviet operatives from sensitive positions. President Truman instituted a system of Loyalty checks through review boards, but Truman himself was unaware of the extent of the real danger. Hoover approached McCarthy with a plan to (a) ease more security risks out of government positions, (b) put pressure on friends and relatives to reveal what they knew about Soviet operatives based upon familial relations or association in various communist front organizations, and (c) gain more knowledge of spy's contacts and operations. It took a willingness on McCarthy's part to stretch the limits of Senate Rules, and there is no indication Hoover disclosed completely to McCarthy the FBI's full knowledge of Soviet espionage activity in the United States for the prior two and half decades. The immediate crisis was so large and potentially catastrophic that McCarthy was willing to act with Hoover and the FBI to help remove the remaining security risks.

Most but not all of Senator McCarthy’s numbered cases were drawn from the “Lee List” or “108 list” of unresolved Department of State security cases compiled by the investigators for the House Appropriates Committee in 1947. Robert E. Lee was the committee's lead investigator and supervised preparation of the list. The Tydings subcommittee also obtained this list. The Lee list, using numbers rather than names, was published in the proceeding of the subcommittee.[102]

Senator McCarthy furnished the Tydings Committee the real names attached to his numbered cases, and the Tydings Committee received the real names attached to the Lee list as well.[103] Over the years that followed all of the names became public one way or another. Additionally, in a series of speeches McCarthy named others as secret Communists, spies, security risks, or participants in the Communist conspiracy.

In 1950 A. S. Brent of the FBI did a thorough review of the 54 files covering the Gregory case in response to a request for information concerning individuals who now were liable to register under Section 20 of the Internal Security Act of 1950. Brent found the facts still insufficient for prosecution under the espionage or related statutes. Brent made specific recommendations handling the cases of Joseph Katz, Mary Price, George Perazich, and Abraham Brothman. Brent noted "It is realized that we are dealing with callous individuals. However, it is felt that we should concentrate our investigative efforts at this time on trying to find a weak spot in the armors of these people"[104] and select several cases with suggestions how to do proceed. Anatole Volkov, the son of Helen Silvermaster and stepson of Greg Silvermaster he says, "if we concentrate on Volkov... All of this, it is felt, will affect the Silvermasters and may possibly persuade them to cooperate." In Lud Ullman's case Brent notes, "it is a common practice ...to contact parents and other relatives...Undoubtedly, an interview with them would disturb Ullman if it came to his attention." Of Duncan Chapin Lee he observes "there may be a way of persuading Lee to talk by interviewing his parents and relatives....If these interviews draw complaints from him then it is felt that we would be in a position to interview him thoroughly concerning the noted discrepancies." Regarding George Silverman Brent proposes, "Silverman would be very sensitive to an approach to his son...it... would disturb his father and might be the thing which will cause Silverman to cooperate with us." On Robert Talbot Miller, III "we should give consideration to closing in on Miller by talking to his father," and of Victor Perlo "we should give consideration to interviewing his parents." Brent cites the 1947 Tamm memo "That one of the subjects ...possibly the weakest member, be contacted...Failling in this respect, the other subjects should be exhaustively interviewed....it would seem logical to conduct such interviews as nearly simultaneously as possible. ...That failing to break any of the subjects, serious consideration be given to exposing this lousy outfit and at least hounding them from the federal service."

Tensions of the times[edit]

- President Truman issued Executive Order 9835 on 22 March 1947 intended to tighten protections against subversive infiltration of the US Government, defining disloyalty as membership on a list of subversive organizations maintained by the Attorney General.

- Beginning 24 June 1948 the first major crisis of the Cold War exposed the rift in the Alliance of World War II which had defeated Germany, when Soviet troops blockaded access points to Berlin, sparking the first Berlin Crisis, and lasting a year.

- On 20 July CPUSA General Secretary Eugene Dennis and 11 others were arrested and indicted under the Smith Act of conspiring to advocate violent overthrow of the US Government.

- On 31 July Elizabeth Bentley testifies before the House Committee on Un-American Activities (HUAC), publicly accusing Harry Dexter White and White House adviser Lauchlin Currie of being Soviet agents.

- 3 August Whittaker Chambers names the first General Secretary of the United Nations Charter meeting and confident of President Roosevelt at the Yalta Conference, Alger Hiss, as well as Harry Dexter White as Communists in testimony before the HUAC.

- 13 August Harry Dexter White, the first head of the International Monetary Fund, a keystone post war institution, denies charges he is a Soviet agent before HUAC and claims he's a loyal New Deal Democrat.

- Three days later on 16 August Harry Dexter White died of a heart attack. His complicity in espionage was later conclusively determined by the FBI through evidence gathered by the Venona project as a Soviet agent code named "Jurist".[105]

- In late summer of 1949, on 29 August the Soviet atomic bomb project was revealed when it exploded a replica of Fat Man; the Soviet Union gained nuclear technology by espionage from the United State with the willing cooperation of government employees and American citizens.

- On 23 September 1949 Truman announces that the Soviets have exploded an atomic bomb.

- 19 October Meredith Gardner and Robert Lamphere secretly meet at Arlington Hall and formally inaugurate full-time FBI/Army Signals Intelligence Service liaison on coded Soviet messages.

- On 1 October Maoist forces were victorious after the effective subversion of President Roosevelt’s support for the Chinese Nationalist government during World War II.

- On 21 January 1950, Alger Hiss was convicted of perjury for testimony before HUAC regarding espionage on behalf of the Soviet Union.

- 24 January Klaus Fuchs confessed in Great Britain to espionage on behalf of the Soviet Union while working on the Manhattan Project at Los Alamos National Laboratory during the War.

- 22 May FBI arrests Harry Gold for espionage.

- On 25 June, the Korean War began when North Korea invaded South Korea; President Truman authorized deployment of American troops while the Allied Powers provided little or no assistance. The United States essentially stood alone in a confrontation that had the prospect of nuclear weapons being used — nuclear weapons technology that had been given to the enemy by US citizens, some within the government.

- On 17 July, Julius Rosenberg was arrested on charges of espionage regarding the transfer of technology to the Soviet Union to build the atomic weapon.

- In May 1951, two members of the Cambridge Five — Donald MacLean, Second Secretary of the British Embassy in Washington, D.C., and Guy Burgess — defected to Moscow after it was discovered MacLean transmitted information on the atom bomb from the British Embassy to the Soviet Union during World War II.

More spy cases[edit]

Coplon[edit]

Philby[edit]

Hiss convicted and the vendetta against Nixon[edit]

A housewife electrocuted and Oppenheimer walks[edit]

- Main article Ethel Rosenberg

Hypocrisy regarding McCarthy's methods[edit]

McCarthy had a confrontation with Boston attorney Joseph Welch in televised hearings. Welch demanded that McCarthy name someone who had belonged to a Communist front organization, and then complained that it was cruel, reckless, and indecent to do so. McCarthy named Welch's associate Fred Fisher as a member of the National Lawyers Guild, who Welch himself had previously outed to the ‘’New York Times’’ six weeks earlier.[8] Welch dishonestly pretended to be shocked, and famously said, "Have you no sense of decency, sir, at long last?"

Social commentator Ann Coulter observes,

| “ | it is difficult to grasp the importance of McCarthy's crusade. But there's a reason 'Communist' now sounds about as threatening as 'monarchist' …. McCarthy made it a disgrace to be a Communist. Domestic Communism could never recover.

Liberals invented the myth of McCarthyism to delegitimize impertinent questions about their own patriotism...Liberals demand that the nation treat enemies like friends and friends like enemies...Any evidence that anyone seeks to harm America is stridently rejected as "no evidence."[106] |

” |

The New Left[edit]

- Main article: New Left

See also[edit]

Further reading[edit]

- FBI Silvermaster file, Morgan to Clegg, January 14, 1947

- Memorandum for the Attorney General, January 27, 1947

- FBI Silvermaster file, Brent to Hennrich, October 30, 1950

References[edit]

- ↑ Symposium: Treason?, By Jamie Glazov, FrontPageMagazine.com , July 25, 2003.

- ↑ Jaffe, Bisson, and Lattimore were all founding board members of the communist controlled Amerasia magazine.

- ↑ Joe McCarthy: Gone But Certainly Not Forgotten, Michael M. Bates, New Media Journal, May 25, 2007.

- ↑ FBI Silvermaster file Vol. 92, pgs. 20 - 21 pdf, January 26, 1947. Biographical details and extended wrap-up on Duncan C. Lee, formerly of OSS, Elizabeth Bentley's allegations concerning him, his contacts with Donald Wheeler and Mary Price, and his employment by the law firm of President Franklin Roosevelt adviser Thomas Corcoran.

- ↑ Venona 927-928 GRU New York to Moscow, June 16, 1943, pg. 1pg. 2; see also June 17, 1943 and June 24, 1943.

- ↑ McCarthyism: Waging the Cold War in America, Newly Uncovered Secret Data Confirm Wisconsin Senator's Major Charges, Human Events, M. Stanton Evans, 05/08/2003.

- ↑ FBI Headquarters File 100-63, Louis Francis Budenz, Internal Security—C, Serial 122.

- ↑ Hayden B. Peake, The Venona Progeny, Naval War College Review, Summer 2000, Vol. LIII, No. 3. [1]

- ↑ FBI Silvermaster file, Ladd to the Director, November 12, 1945, Vol. 8, pg. 3 pdf.

- ↑ FBI Silvermaster file, Ladd to the Director, November 12, 1945, Vol. 8, pg. 6 pdf.

- ↑ Hoover to Frederick B. Lyon, 24 September 1945, Central Intelligence Agency, Igor Gouzenko file. 5 pages.

- ↑ FBI Silvermaster file, Underground Espionage Organization (NKVD) in Agencies of the United States Government", Vol. 23, pgs. 55 - 272, February 21, 1946. Includes alphabetical index at end.

- ↑ FBI Silvermaster file, Memorandum for the Attorney General, December 20, 1946, Vol. 81, pgs. 55 - 56 pdf. In transmitting a summary of the investigation on Harry Magdoff, Hoover urges the Attorney General to give consideration to the overall facts of the case before making the information available to any other government official. Hoover complains that a summary report prepared for the Secretary of the Treasury had been "lost" and a copy furnished to the White House was found in a desk drawer at the War Assets Administration -- the agency Greg Silvermaster had been working in.

- ↑ FBI Silvermaster file, Morgan to Clegg, January 14, 1947.

- ↑ FBI Silvermaster file, Tamm to the Director, January 23, 1947, Vol. 93, pgs. 20 -22 pdf.

- ↑ FBI Silvermaster file, Memorandum for the Attorney General, January 27, 1947.

- ↑ John Emil Peurifoy, Foreign Service Office & United States Ambassador, Arlington National Cemetery Website, retrieved 21 March 2007.

- ↑ NSA Archives, National Cryptological Museum, Venona Chronology; "~September 1: Col. Carter Clarke briefs the FBI's liaison officer Robert J. Lamphere on the break into Soviet diplomatic traffic. September: Carter W. Clarke of G-2 advises S. Wesley Reynolds, FBI, of successes at Arlington Hall on KGB espionage messages."

- ↑ Robert Louis Benson, and Michael Warner, eds. VENONA: Soviet Espionage and the American Response, 1939-1957, pg. 9. Washington, DC: National Security Agency/Central Intelligence Agency, 1996. Laguna Hills, CA: Aegean Park Press, 1996. Robert L. Benson, works in the Office of Security, National Security Agency; Michael Warner, Deputy Chief of the CIA History Staff.

- ↑ Moynihan Commission on Government Secrecy, Appendix A, 7. The Cold War; "In November 1945 Elizabeth Bentley informed the FBI of her activities as a Soviet courier, which in turn led to renewed interest in Chambers. In late August or early September 1947, the FBI was informed that the Army Security Agency had begun to break into Soviet espionage messages".

- ↑ National Security Agency, Venona Archives, Introductory History of VENONA and Guide to the Translations,The VENONA Breakthroughs; "An Arlington Hall report on 22 July 1947 showed that the Soviet message traffic contained dozens, probably hundreds, of covernames, many of KGB agents, including ANTENNA and LIBERAL (later identified as Julius Rosenberg). One message mentioned that LIBERAL's wife was named "Ethel." General Carter W. Clarke, the assistant G-2, called the FBI liaison officer to G-2 and told him that the Army had begun to break into Soviet intelligence service traffic, and that the traffic indicated a massive Soviet espionage effort in the U.S.

- ↑ FBI Silvermaster file, Vol. 93, February 1947. Summary: Hoover memo expressing doubts about successful prosecution and statement that, because of leaks by the Department, "there is little which can be expected from any action now." Further Hoover memo of February 4, 1947, saying "investigative reports in this case would not be furnished to the Criminal Division [of Justice] because of the possibility that some of the material therein would be publicized." See also January 27, 1947 J. Edgar Hoover Memorandum for the Attorney General, pgs. 31 -32.

- ↑ National Counterintelligence Center (NACIC), Counterintelligence Reader, Vol. 3, Chap. 1, pg.47, "Polls taken at the time revealed that a majority of Americans believed that Communism at home and abroad was a serious threat to US security".

- ↑ Margaret Chase Smith, Declaration of Conscience, pg. 2, 1 June 1950, U.C. Congress, Senate, Congressional Record, 81st Congress, 2nd sess., pp. 7894-95. "The Democratic administration has greatly lost the confidence of the American people by its complacency to the threat of communism here at home and the leak of vital secrets to Russia through key officials of the Democratic administration. There are enough proved cases to make this point without diluting our criticism with unproved charges...there have been enough proved cases, such as the Amerasia case, the Hiss case, the Coplon case, the Gold case, to cause nationwide distrust and strong suspicion that there may be something to the unproved, sensational accusations".

- ↑ J. Edgar Hoover, Testimony before House Appropriations Committee, 2/7/1950.

- ↑ The Atom Spy Case, FBI History, fbi.gov

- ↑ W. K. Benons to Chairman, Scientific Intelligence Committee, Failure of the JAEIC To Receive Counter Espionage Information having Positive Intelligence Value, 9 February 1950, Central Intelligence Agency.

- ↑ FBI Venona file

- ↑ Ralph de Toledano and Victor Lasky, Seeds of Treason, (NY: Funk and Wagnalls, 1950), pg. 107.

- ↑ Toledano and Lasky, Seeds of Treason, pg. 109.

- ↑ McCarthy Was Right, Excerpts from The Venona Program, September 04, 2006. Retrieved from Townhall.com September 04, 2007.

- ↑ In the Enemy’s House: Venona and the Maturation of American Counterintelligence, John F. Fox, Jr., Presented at the 2005 Symposium on Cryptologic History, 10/27/2005.

- ↑ Report of the Commission on Protecting and Reducing Government Secrecy. United States Government Printing Office. Appendix A, Part 6, Page 36 pdf.

- ↑ 1822 Venona Washington to Moscow 30 March 1945. National Security Agency National Cryptologic Museum. Retrieved September 04, 2007.

- ↑ Secrets, Lies, and Atomic Spies, NOVA Transcript, PBS Airdate: February 5, 2002. Retrieved from PBS.org September 04, 2007.

- ↑ Who was Venona's “Ales”? Cryptanalysis and the Hiss case. Eduard Mark, Intelligence and National Security, Volume 18, Number 3, September 2003 , pp. 45-72(28)

- ↑ Activities of U.S. Citizens Employed by the UN, second report of the SISS (March 22, 1954), p. 12.

- ↑ Toledano and Lasky, Seeds of Treason, pg. 83 (pg. 91 pdf).

- ↑ The Case of Alger Hiss, Time magazine, Feb. 13, 1950. Contemporaneous report 3 days after Sen. McCarthy's Wheeling, West Virginia Speech.

- ↑ Hiss defenders covering for the `old man', by Ralph De Toledano, Insight on the News, Dec 17, 2001.

- ↑ Toledano and Lasky, Seeds of Treason, pg. 86 (pg. 94 pdf).

- ↑ Vitali Pavlov, "Operation Snow," News of Intelligence and Counter Intelligence, Moscow, August 1995, pgs. 5-6.

- ↑ Soviet penetration of the U.S. gets fresh look, Allan H Ryskind, Human Events, Jan 29, 2001. Review of Romerstein and Breindel, The Venona Secrets.

- ↑ See also Sinkiang,Chinese Eastern Railroad ZoneKiangsi Soviet Republic, 1 Dec 1931 - 15 Oct 1934.

- ↑ Tragedy and Hope: A History of the World in Our Time, Carroll Quigley, Collier-Macmillan, 1966, pg. 739. ISBN 0-945001-10-X

- ↑ Jerrold L. Schecter and Leona Schecter, Sacred Secrets: How Soviet Intelligence Operations Changed American History, Washington, DC : Brassey’s, 2002, pgs. 31, 33.

- ↑ Memorandum by Secretary Morgenthau, November 17, 1941, Foreign Relations, 1941, IV, pp. 606-613. Dr. Kubek in 1959 wrote "at this time is altogether improbable" that White would have acted in collaboration with Currie and one of the Hiss brothers whom he was known to have a relationship, or "at their instigation." This is in keeping with the version of events told by Vitali Pavlov in 1995 that White received through him directions from Moscow. Kubek further adds White heard his draft was being tampered with in the State Department where the Hiss brothers worked and wished to have the tampering stopped. Communism at Pearl Harbor, Kubek, 1959, pg. 19.

- ↑ Henry L Stimson's Diary, November 25, 1941, Pearl Harbor Attack, Part II, p. 5433. For other interpretations of Stimson's statement Cf. Charles Beard, President Roosevelt and the Coming of the War, 1941 (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1948). Chapter XVII; Charles C. Tansil, Back Door to War (Chicago: Henry Regnery, 1952), pp. 645-652; George Morgenstern, Pearl Harbor (New York: Devin-Adair Company, 1947), Chapter XlX. Roosevelt's fear was not that Japan would attack the United States, but that she might not.

- ↑ Pearl Harbor Attack. Part 39, p. 502; Part 2, p. 5177; Part 3, p. 1149.

- ↑ Tragedy and Hope: A History of the World in Our Time, Carroll Quigley, Collier-Macmillan, 1966, pg. 741. ISBN 0-945001-10-X

- ↑ FBI Silvermaster file, Vol. 16, pgs. 98 - 100 pdf.

- ↑ FBI Silvermaster file, Vol. 16, pg. 101; pgs. 102 -104 pdf.

- ↑ Was Oppenheimer a Soviet Spy? A Roundtable Discussion with Jerrold and Leona Schecter, Gregg Herken and Hayden Peake. The Cold War International History Project. The Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars. Peake, curator of the Central Intelligence Agency’s (CIA) Historical Intelligence Collection [2], states, "The content of the Sacred Secrets Merkulov letter is also questioned on the point of whether it is or is not "smoking gun" evidence that Robert Oppenheimer was a Soviet source or agent while he worked on the atom bomb project during WWII. ...In short, I accept the letter and its implications."

- ↑ H.B. Laes, Theory of Fielding, KGB Organization. Retieved September 04, 2007. [3]

- ↑ Merkulov to Beria, 2 October 1944. The letter states, "In 1942 one of the leaders of scientific work on [uranium] in the USA, Professor Oppenheimer while being an unlisted (nglastny) member of the apparat of Comrade Browder informed us about the beginning of work. On the request of Comrade Kheifitz, confirmed by Comrade Browder, he provided cooperation in access to research for several of our tested sources including a relative of [Comrade Browder]"

- ↑ Pavel Sudoplatov, Special Tasks : Memoirs of an Unwanted Spymaster, Little Brown and Company, London, 1994, pg. 3.

- ↑ Sudoplatov, Special Tasks, pg. 172.

- ↑ FBI Special Agent in Charge William Borden, who investigated Oppenheimer's CPUSA connections and was requested to make a determinaion of his findings, wrote "He was a vigorous supporter of the H-bomb program until August 6, 1945, (Hiroshima), on which day he personally urged each senior individual working in this field to desist... The central problem is assessing the degree of likelihood that he in fact... during the crucial 1939-1942 period...became an actual espionage and policy instrument of the Soviets. ... my opinion is that...the worst is in fact truth.” Letter from William L. Borden to J. Edgar Hoover, November 7, 1953.

- ↑ McCarthy stated during the Executive Session hearings, "I noticed with some interest Oppenheimer’s articles in regard to the H-bomb, for example; he vigorously opposed our proceeding with any experimentation in the development of the H-bomb. When he lost out in that, he now has taken the position that we should not have an air force capable of delivering that bomb. Maybe I am simplifying it a bit, but in fact that is his argument. His argument has been that we should build a screen of defense around this nation." McCarthy Hearings, Executive Session Transcripts, September 15, 1953, Vol. 3, Pgs. 37 - 38 pdf.

- ↑ Sudoplatov, Special Tasks, pg. 195.

- ↑ Sudoplatov, Special Tasks, pg. 190.

- ↑ Sudoplatov, Special Tasks, pg. 197.

- ↑ Sudoplatov, Special Tasks, pg. 197.

- ↑ Sudoplatov, Special Tasks, pg. 205 - 207.

- ↑ The Roosevelt Myth, John T. Flynn, Fox and Wilkes, 1948, Book 3, Chapter 9, Section 2. Roosevelt's Great Design and Casablanca, pg. 345 pdf.

- ↑ Townsend Hooper and Douglas Brinkley, FDR and the Creation of the U.N, New Haven, 2000, pgs. 45 50.

- ↑ Joint Four Power Declaration, Moscow Conference, October, 1943.

- ↑ Red Star Over China by Edgar Snow, New York, 1937.

- ↑ Testimony of Stanley K. Hornbeck, February 15, 1952. U. S. Congress, Senate Committee on the Judiciary, Internal Security Subcommittee, Institute of Pacific Relations Hearings, 82nd Congress, First Session (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1951), Part 9, pp. 3209-10.

- ↑ McCarthyism: Waging the Cold War in America, Newly Uncovered Secret Data Confirm Wisconsin Senator's Major Charges, Human Events, M. Stanton Evans, 05/08/2003.

- ↑ Elizabeth Bentley's testimony in Institute of Pacific Relations, Hearings, Part 2, Exhibit No. 1ll, 112, pp. 433-434.

- ↑ Testimony of Cordell Hull, November 23, 1945. Pearl Harbor Attack, Part 2, 434-435 and Unnumbered Volume, pp. 36-37.

- ↑ Communism at Pearl Harbor, How the Communists Helped to Bring on Pearl Harbor and Open up Asia to Communinization, Dr. Anthony Kubek, Dallas Texas, Teaching Publishing Company, 1959. Dr. Anthony Kubek wrote the Introduction of the U.S. Senate Committee on the Judiciary, Senate Internal Security Subcommittee, Report on the Morgenthau Diaries. The records of the Morgenthau Diary Study, 1953-65 consist largely of copies of portions of memorandums, correspondence, transcripts of meetings, and other records preserved by Secretary Morgenthau in order to document his tenure. The original records are in the custody of the Franklin D. Roosevelt Library in Hyde Park, NY. In 1965, the SISS issued a two volume committee print entitled Morgenthau Diary (China), Edited by Dr. Anthony Kubek, containing entries from the records at the Franklin D. Roosevelt Library selected to illustrate the implementation of Roosevelt administration policy in China. According to Dr. Kubek, the subcommittee wanted to produce a documentary history on the subject and "also indicate the serious problem of unauthorized, uncontrolled and often dangerous power exercised by non-elected officials," specifically Harry Dexter White. White was a major figure in Senator William Jenner's investigation of interlocking subversion in Government departments in 1953. The bipartisan investigation lasted for twelve years, and the Subcommittee's Report took another two years to write. [4] Dr. Anthony Kubek also is a recognized expert on the subject of U.S. Naval Intelligence's Operation Magic, the effort to crack Japanese diplomatic ciphers. [5]

- ↑ Testimony of Louis Francis Budenz, August 22, 1951. Institute of Pacific Relations, Hearings. Part 2, pp. 522-23.

- ↑ Tongue-Tied, Time magazine, Feb. 07, 1944.

- ↑ The Yalta Betrayal, Felix Wittmer, Claxton Printers, 1953, pg. 36.

- ↑ Yalta Betrayal, Wittmer, 1953, pg. 58. Retrieved from GELO.com of Czechoslovakia 05/08/07.

- ↑ US Senate, 82nd Congress, 2nd Session, Committee on the Judiciary, Institute of Pacific Relations, Report No. 2050, p. 223.

- ↑ US Senate, 82nd Congress, 1st Session, Committee on the Judiciary, Institute of Pacific Relations, Part V, pp. 1302, 1206.

- ↑ US Senate, 82nd Congress, 2nd Session, Committee on the Judiciary, Institute of Pacific Relations, Report No. 2050, p. 223.

- ↑ U.S. Code Title 50 Chapter 23 Subchapter IV § 841 Findings and declarations of fact, "The Congress finds and declares that the Communist Party of the United States, although purportedly a political party, is in fact an instrumentality of a conspiracy to overthrow the Government of the United States...the policies and programs of the Communist Party are secretly prescribed for it by the foreign leaders...the Communist Party acknowledges no constitutional or statutory limitations upon its conduct...gives scant indication of capacity ever to attain its ends by lawful political means. The peril inherent in its operation arises …from its failure to acknowledge any limitation as to the nature of its activities, and its dedication to the proposition that the present constitutional Government of the United States ultimately must be brought to ruin by any available means, including resort to force and violence. Holding that doctrine, its role as the agency of a hostile foreign power renders its existence a clear present and continuing danger to the security of the United States. It is the means whereby individuals are seduced into the service of the world Communist movement, trained to do its bidding, and directed and controlled in the conspiratorial performance of their revolutionary services."

- ↑ The Yalta Betrayal, Felix Wittmer, Caxton Printers, 1953, pg. 59.

- ↑ David Rees, Harry Dexter White; a Study in Paradox, London, 1974, pg. 333.

- ↑ John Earl Haynes and Harvey Klehr, Venona: Decoding Soviet Espionage in America, New Haven Yale University Press, 2000, pp. 142-145 ISBN 0-300-08462-5

- ↑ David Rees, Harry Dexter White; a Study in Paradox, pg. 326.

- ↑ Anne W. Carroll, Who Lost China, 1996. Retrieved from www.ewtn com/library/ August 16, 2007.

- ↑ Richard C. Thornton, China: A Political History, 1917-1980, Boulder CO 1982, pg. 208.

- ↑ Military Situation in the Far East, Hearings before the Committee on Armed Services and the Committee on Foreign Relations, U.S. Senate, 82nd Congress (Washington, 1951), p. 558.

- ↑ Tang Tsou, America's Failure in China, 1941-1945, Chicago 1964, pg. 457.

- ↑ Tang Tsou, America's Failure in China, 1941-1945, Chicago 1964, pg. 429.

- ↑ New York Times, January 13, 1950.

- ↑ Guide to the Records of the U.S. Senate at the National Archives, Records of the Morgenthau Diary Study, 1953-65.

- ↑ Rectification in Yan’an—Creating the Most Fearsome Methods in Persecution, The Beginnings of the Chinese Communist Party, Epoch Times Commentaries on the Chinese Communist Party - Part 2, Dec 11, 2004.

- ↑ Report on the Morgenthau Diaries prepared by the Subcommittee of the Senate Committee of the Judiciary appointed to investigate the Administration of the Internal Security Act and other Internal Security Laws, Introduction, by Dr. Anthony Kubek, Professor of History at Dallas University, November 1967, United States Government Printing Office, two volumes, v.i., pg. 80.

- ↑ U.S. Senate Committee on the Judiciary, Report on the Institute of Pacific Relations, Washington 1952, pg. 11.

- ↑ McCarthyism: Waging the Cold War in America, by M. Stanton Evans, Human Events, 05/30/1997. Updated 05/08/2003.

- ↑ U.S. Senate Committee on the Judiciary, Report on the Institute of Pacific Relations, Washington 1952.

- ↑ While You Slept : Our Tragedy in Asia and Who Made It, John T. Flynn, New York : The Devin - Adair Company, 1951, pgs 9-10 pdf.

- ↑ Tragedy and Hope: A History of the World in Our Time, Carroll Quigley, Collier-Macmillan, 1966, pg. 986. ISBN 0-945001-10-X

- ↑ Thomas Patrick Carroll, The Case Against Intelligence Openness, International Journal of Intelligence and Counterintelligence, 2001, Vol. 14, Nol. 4, pgs. 559 - 574. [6]

- ↑ The Origins of McCarthyism, What did Harry Truman know, and when did he know it? by Robert D. Novak, The Weekly Standard, 06/30/2003, Volume 008, Issue 41.

- ↑ U.S. Senate Committee on Foreign Relations, State Department Employee Loyalty Investigations (Washington, D.C.: U.S. Govt. Print. Off., 1950).

- ↑ McCarthy to Tydings, 18 March 1950 with attached list.

- ↑ FBI Memo Brent to Hennrich, October 30, 1950.

- ↑ FBI Memo Ladd to the Director, October 16, 1950, Identifying Harry Dexter White as agent Jurist.

- ↑ Coulter, Ann Treason: Liberal Treachery From the Cold War to the War on Terrorism©2003 Crown Forum, New York, New York, pp. 1-2

External links[edit]

- The Good Occupation, By Yoshiro Miwa & J. Mark Ramseyer, 05/2005.

- McCarthyism: The Rosetta Stone of Liberal Lies, by Ann Coulter, Human Events, 11/07/2007.

Categories: [Cold War] [Espionage] [New Deal] [1950s] [Anti-Communism]

↧ Download as ZWI file | Last modified: 03/11/2023 19:07:58 | 9 views

☰ Source: https://www.conservapedia.com/McCarthyism | License: CC BY-SA 3.0

ZWI signed:

ZWI signed:

KSF

KSF