La Crosse Encephalitis

From Mdwiki

From Mdwiki | La Crosse encephalitis | |

|---|---|

| Other names: La Crosse Encephalitis Virus Infection, La Crosse, La Crosse Encephalitis[1] | |

| |

| Specialty | Infectious disease |

| Symptoms | Nausea, headache, vomiting in milder cases and seizures, coma, paralysis |

| Causes | La Crosse encephalitis virus |

| Diagnostic method | Blood test |

| Differential diagnosis | Hyponatremia,Wernickes encephalitis,Drug intoxication |

| Prevention | Repellent such as DEET and picaridin |

| Treatment | No specific therapy is available |

| Frequency | 787 cases (2004-13) |

La Crosse encephalitis is an encephalitis caused by an arbovirus (the La Crosse virus) which has a mosquito vector (Ochlerotatus triseriatus synonym Aedes triseriatus).[3]

La Crosse encephalitis virus (LACV) is one of a group of mosquito-transmitted viruses that can cause encephalitis, or inflammation of the brain. LAC encephalitis is rare; in the United States, about 80–100 LACV disease cases are reported each year, although it is believed to be under-reported due to minimal symptoms experienced by many of those affected.[4]

Signs and symptoms[edit | edit source]

It takes 5 to 15 days after the bite of an infected mosquito to develop symptoms of LACV disease. Symptoms include nausea, headache, vomiting in milder cases and seizures, coma, paralysis and permanent brain damage in severe cases.[5][6][7]

LAC encephalitis initially presents as a nonspecific summertime illness with fever, headache, nausea, vomiting and lethargy. Severe disease occurs most commonly in children under the age of 16 and is characterized by seizures, coma, paralysis, and a variety of neurological sequelae after recovery. Death from LAC encephalitis occurs in less than 1% of clinical cases. In many clinical settings, pediatric cases presenting with CNS involvement are routinely screened for herpes or enteroviral causes.[5][8][6][9]

As with many infections, the very young, the very old and the immunocompromised are at a higher risk of developing severe symptoms.[10]

Related conditions[edit | edit source]

Similar diseases that are spread by mosquitoes include: Western and Eastern equine encephalitis, Japanese encephalitis, Saint Louis encephalitis and West Nile virus.[11]

Cause[edit | edit source]

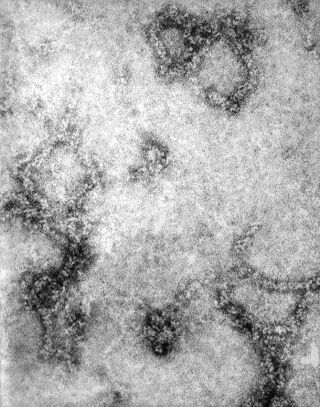

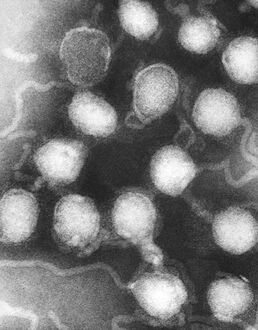

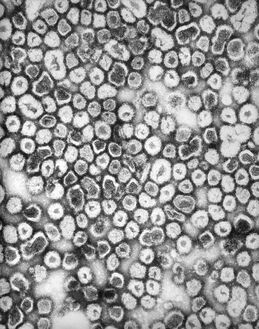

The La Crosse encephalitis virus is a type of arbovirus called a bunyavirus,[12] the Bunyavirales are mainly arboviruses.

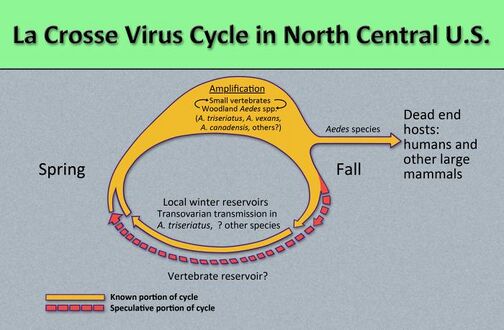

Most cases of LAC encephalitis occur in children at an early age. LAC virus is a zoonotic pathogen cycled between the daytime-biting treehole mosquito, Aedes triseriatus, and vertebrate amplifier hosts in deciduous forest habitats.[5] [13]

The virus is maintained over the winter by transovarial transmission in mosquito eggs. If the female mosquito is infected, she may lay eggs that carry the virus, and the adults coming from those eggs may be able to transmit the virus to animals and to humans.Anyone bitten by a mosquito in an area where the virus is circulating can get infected with LACV. The risk is highest for people who live, work or recreate in woodland habitats, because of greater exposure to potentially infected mosquitoes.[14][13]

Mechanism[edit | edit source]

In terms of the mechanism of La Crosse encephalitis we find that via a mosquitos sting it is transmitted under the skin. Surface glycoproteins have to do with the transmission of the virus- G1 protein moderates the attachment primary to human cells, and G2 protein attaches mosquito cells, thereafter replication begins and results in systemic infection.[5]

Vascular endothelial cells penetration results in neuro-invasion (infection of neurons).[5]

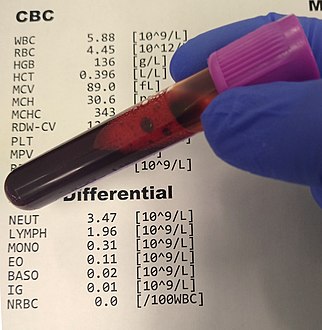

Diagnosis[edit | edit source]

The diagnosis of this condition, La Crosse encephalitis is done via the following (enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay testing for IgM and IgG antibodies in serum[5]) :[15]

- Blood test

- Spinal fluid test

- EEG (detect seizures)

Lumbar puncture, swirls are tincture of iodine.

Differential diagnosis[edit | edit source]

The DDx for La Crosse encephalitis is as follows:[5]

- Hyponatremia

- Wernickes encephalitis

- Drug intoxication

- Focal seizures

- Epidural hematoma

- Cryptococcal meningitis

- Varicella-zoster virus encephalitis

- Herpes simplex virus encephalitis

Prevention[edit | edit source]

People reduce the chance of getting infected with LACV by preventing mosquito bites. There is no vaccine or preventive drug.[16]

Prevention measures against LACV include reducing exposure to mosquito bites. Use repellent such as DEET and picaridin, while spending time outside, especially at during the daytime - from dawn until dusk. Aedes triseriatus mosquitoes that transmit (LACV) are most active during the day. Wear long sleeves, pants and socks while outdoors. Ensure all screens are in good condition to prevent mosquitoes from entering your home. Aedes triseriatus prefer treeholes to lay eggs in. Also, remove stagnant water such as old tires, birdbaths, flower pots, and barrels.[17]

Treatment[edit | edit source]

No specific therapy is available at present for La Crosse encephalitis, and management is limited to alleviating the symptoms and balancing fluids and electrolyte levels. [16]

Epidemiology[edit | edit source]

La Crosse encephalitis was discovered in 1965, after the virus was isolated from stored brain and spinal tissue of a child who died of an unknown infection in La Crosse, Wisconsin in 1960.[18]

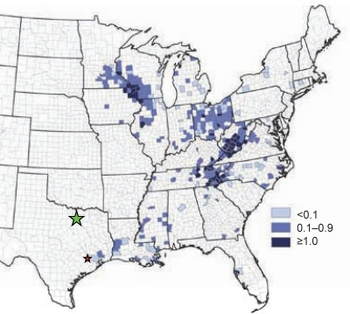

It occurs in the Appalachian and Midwestern regions of the United States. Recently there has been an increase of cases in the South East of the United States. An explanation to this may be that the mosquito Aedes albopictus is also an efficient vector of La Crosse virus. Aedes albopictus is a species that has entered the US and spread across the SE of the US and replaced Aedes aegypti in some areas.[19][20][21]

Historically, most cases of LAC encephalitis occur in the upper Midwestern states that is Minnesota, Wisconsin, Iowa, to name a few.[22] Recently, more cases are being reported from states in the mid-Atlantic like Virginia and North Carolina and southeastern regions of the country. It has long been suspected that LAC encephalitis has a broader distribution and a higher incidence in the eastern United States, but is under-reported because the causal agent is often not specifically identified.LAC encephalitis cases occur primarily from late spring through early fall.[23][20][24]

According to the CDC, between 2004 and 2013 there were 787 total cases of La Crosse encephalitis and 11 deaths in the U.S.[25]

Looking at the distribution of cases across the United States by state, between 2004 and 2013 the most cases of La Crosse encephalitis was in North Carolina. North Carolina had 184 total cases, followed by Ohio with 178 total cases.[26]

Research[edit | edit source]

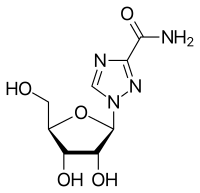

Intravenous ribavirin is effective against La Crosse encephalitis virus in the laboratory, and several studies in patients with severe, brain biopsy confirmed, La Crosse encephalitis are ongoing.[27][5][28]

In a trial with 15 children being infected with La Crosse viral encephalitis were treated at certain phases with ribavirin (RBV). RBV appeared to be safe at moderate doses.[29]

At escalated doses of RBV, adverse events occurred and then the trial was discontinued. Nonetheless, this was the largest study of antiviral treatment for La Crosse encephalitis.[29]

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ "La Crosse encephalitis". National Library of Medicine. Archived from the original on 4 April 2023. Retrieved 4 April 2023.

- ↑ Arragain, Benoît; Durieux Trouilleton, Quentin; Baudin, Florence; Provaznik, Jan; Azevedo, Nayara; Cusack, Stephen; Schoehn, Guy; Malet, Hélène (16 February 2022). "Structural snapshots of La Crosse virus polymerase reveal the mechanisms underlying Peribunyaviridae replication and transcription". Nature Communications. 13 (1): 902. doi:10.1038/s41467-022-28428-z. ISSN 2041-1723. Archived from the original on 21 October 2022. Retrieved 12 April 2023.

- ↑ McJunkin, J. E.; de los Reyes, E. C.; Irazuzta, J. E.; Caceres, M. J.; Khan, R. R.; Minnich, L. L.; Fu, K. D.; Lovett, G. D.; Tsai, T.; Thompson, A. (March 2001). "La Crosse Encephalitis in Children". The New England Journal of Medicine. 344 (11): 801–7. doi:10.1056/NEJM200103153441103. PMID 11248155.

- ↑ "Epidemiology & Geographic Distribution | la Crosse encephalitis | CDC". 2018-09-14. Archived from the original on 2018-12-07. Retrieved 2021-09-10.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 5.5 5.6 5.7 Khan, Usaamah M.; Gudlavalleti, Aashrai (2023). "La Crosse Encephalitis". StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing. Archived from the original on 1 April 2023. Retrieved 1 April 2023.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 "Symptoms, Diagnosis, & Treatment | La Crosse encephalitis | CDC". www.cdc.gov. 7 November 2022. Archived from the original on 20 October 2022. Retrieved 2 April 2023.

- ↑ "La Crosse encephalitis - About the Disease - Genetic and Rare Diseases Information Center". rarediseases.info.nih.gov. Archived from the original on 18 May 2022. Retrieved 4 April 2023.

- ↑ "Orphanet: La Crosse encephalitis". www.orpha.net. Archived from the original on 23 October 2021. Retrieved 1 April 2023.

- ↑ "Clinical Evaluation & Disease | La Crosse encephalitis | CDC". www.cdc.gov. 7 March 2023. Archived from the original on 10 April 2023. Retrieved 11 April 2023.

- ↑ "Infections in the Immunocompromised Host: Practice Essentials, The Child with Frequent Infections, Immunocompromising Conditions". Medscape. 17 October 2021. Archived from the original on 31 March 2023. Retrieved 6 April 2023.

- ↑ Nicoll, J. A. R.; Bone, Ian; Graham, David (24 November 2006). Adams & Graham's Introduction to Neuropathology 3Ed. CRC Press. p. 141. ISBN 978-0-340-81197-9. Archived from the original on 9 April 2023. Retrieved 9 April 2023.

- ↑ Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) (January 2009). "Possible Congenital Infection with La Crosse Encephalitis Virus — West Virginia, 2006–2007". MMWR. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 58 (1): 4–7. PMID 19145220. Archived from the original on 2019-09-29. Retrieved 2021-09-10.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 McJunkin, J. E.; Khan, R. R.; Tsai, T. F. (March 1998). "California-La Crosse encephalitis". Infectious Disease Clinics of North America. 12 (1): 83–93. doi:10.1016/s0891-5520(05)70410-4. ISSN 0891-5520. Archived from the original on 4 April 2023. Retrieved 5 April 2023.

- ↑ Smith, J. E.; Dunn, A. M. (June 1991). "Transovarial transmission". Parasitology Today (Personal Ed.). 7 (6): 146–148. doi:10.1016/0169-4758(91)90283-t. ISSN 0169-4758. Archived from the original on 2022-08-02. Retrieved 2023-04-10.

- ↑ "Frequently Asked Questions | La Crosse encephalitis | CDC". www.cdc.gov. 7 January 2022. Archived from the original on 25 January 2022. Retrieved 24 January 2022.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 "Treatment and Prevention | La Crosse encephalitis | CDC". www.cdc.gov. 7 March 2023. Archived from the original on 6 October 2022. Retrieved 2 April 2023.

- ↑ "Prevention". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 11 April 2016. Archived from the original on 7 December 2018. Retrieved 6 December 2016.

- ↑ Thompson, W.H.; Kalfayan, B.; Anslow, R.O. (1965). "Isolation of California encephalitis virus from a fatal human illness". Am. J. Epidemiol. 81 (2): 245–253. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a120512. PMID 14261030.

- ↑ Bewick, Sharon; Agusto, Folashade; Calabrese, Justin M.; Muturi, Ephantus J.; Fagan, William F. (November 2016). "Epidemiology of La Crosse Virus Emergence, Appalachia Region, United States". Emerging Infectious Diseases. 22 (11): 1921–1929. doi:10.3201/eid2211.160308. ISSN 1080-6059. Archived from the original on 2022-06-20. Retrieved 2023-04-03.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 Harding, S.; Greig, J.; Mascarenhas, M.; Young, I.; Waddell, L. A. (2019). "La Crosse virus: a scoping review of the global evidence". Epidemiology and Infection. 147: e66. doi:10.1017/S0950268818003096. Archived from the original on 5 April 2023. Retrieved 5 April 2023.

- ↑ Rowe, R. D.; Odoi, A.; Paulsen, D.; Moncayo, A. C.; Trout Fryxell, R. T. (3 September 2020). "Spatial-temporal clusters of host-seeking Aedes albopictus, Aedes japonicus, and Aedes triseriatus collections in a La Crosse virus endemic county (Knox County, Tennessee, USA)". PLOS ONE. 15 (9): e0237322. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0237322. Archived from the original on 13 April 2023. Retrieved 13 April 2023.

- ↑ "Encephalitis". National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke. Archived from the original on 25 March 2023. Retrieved 11 April 2023.

- ↑ "Statistics & Maps | La Crosse encephalitis | CDC". www.cdc.gov. 13 January 2023. Archived from the original on 3 October 2022. Retrieved 3 April 2023.

- ↑ "ArcGIS Web Application". wwwn.cdc.gov. Archived from the original on 15 March 2023. Retrieved 12 April 2023.

- ↑ "La Crosse virus disease cases and deaths reported to CDC by year and clinical presentation, 2004-2013" (PDF). Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Archived (PDF) from the original on 28 April 2019. Retrieved 4 December 2016.

- ↑ "La Crosse virus disease cases reported to CDC by state, 2004–2013" (PDF). Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Archived (PDF) from the original on 20 December 2016. Retrieved 8 December 2016.

- ↑ Haddow, Andrew D.; Haddow, Alastair D. (February 2009). "The use of oral ribavirin in the management of La Crosse viral infections". Medical Hypotheses. 72 (2): 190–192. doi:10.1016/j.mehy.2008.05.043. ISSN 0306-9877. Archived from the original on 1 April 2023. Retrieved 8 April 2023.

- ↑ McJunkin, J. E.; Khan, R.; de los Reyes, E. C.; Parsons, D. L.; Minnich, L. L.; Ashley, R. G.; Tsai, T. F. (February 1997). "Treatment of severe La Crosse encephalitis with intravenous ribavirin following diagnosis by brain biopsy". Pediatrics. 99 (2): 261–267. doi:10.1542/peds.99.2.261. ISSN 1098-4275. Archived from the original on 2023-04-01. Retrieved 2023-04-09.

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 McJunkin, JE (October 2011). "Safety and pharmacokinetics of ribavirin for the treatment of la crosse encephalitis". The Pediatric Infectious Disease Journal. 30 (10): 860–5. doi:10.1097/INF.0b013e31821c922c. PMID 21544005. S2CID 37884333.

External links[edit | edit source]

| Classification | |

|---|---|

| External resources |

- "La Crosse Encephalitis". CDC. 2018-05-03. Archived from the original on 2022-01-25. Retrieved 2012-02-25.

- Directors of Health Promotion and Education Facts Sheet La Crosse Encephalitis

Categories: [Orthobunyaviruses] [Rodent-carried diseases] [Zoonoses] [Brain disorders] [Viral encephalitis]

↧ Download as ZWI file | Last modified: 01/23/2024 16:42:37 | 3 views

☰ Source: https://mdwiki.org/wiki/La_Crosse_encephalitis | License: CC BY-SA 3.0

_(1).png)

.jpg)

KSF

KSF