Hepatitis

From Nwe

From Nwe |

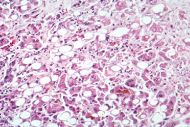

Alcoholic hepatitis evident by fatty change, cell necrosis, Mallory bodies |

|

|---|---|

| ICD-10 | K75.9 |

| ICD-O: | |

| ICD-9 | 573.3 |

| OMIM | [1] |

| MedlinePlus | 001154 |

| eMedicine | / |

| DiseasesDB | 20061 |

Hepatitis is an inflammation of the liver. This gastroenterological disease (digestive system disease) may arise from a wide variety of causes, including viral infection, drugs, metabolic disorders, toxins, alcohol consumption, bacteria, parasites, and a cell-mediated immune response against the body's own liver.

A number of the causes of hepatitis relate to personal and social responsibility, such as viral hepatitis from consuming contaminated food and water, sexual transmission, or tattoos, or overconsumption of alcohol or the popular painkiller acetaminophen. Some drugs on the market, such as certain anti-diabetic and antiretroviral drugs, have been connected to incidences of hepatitis as well.

The clinical signs and prognosis, as well as the therapy, depend on the cause.

Signs and symptoms

Hepatitis is an inflammation of the liver characterized by malaise (generalized weakness), joint aches, fever, itching, abdominal pain (especially right hypochondrial), vomiting, loss of appetite, distaste for cigarettes, dark urine, lightening of stool color, hepatomegaly (enlarged liver), and jaundice (icterus, yellowing of the eyes and skin).

It is important to note that these manifestations are common despite the cause of the disease. Some chronic forms of hepatitis show very few of these signs and are only present when the longstanding inflammation has led to the replacement of liver cells by connective tissue; this disease process is referred to as cirrhosis of the liver. Cirrhosis can also occur upon repeated attacks of hepatitis, as most commonly seen in the form of alcoholic hepatitis.

Certain liver function tests, which mostly measure liver enzymes in the blood, indicate the diagnosis of hepatitis.

Types of hepatitis

Hepatitis can be caused by several different factors. For example, it can be due to a viral infection or it can be drug induced.

Viral

Most cases of acute hepatitis are due to viral infections:

- Hepatitis A

- Hepatitis B

- Hepatitis C

- Hepatitis B with D

- Hepatitis E

- Hepatitis G

In addition to the hepatitis viruses, other viruses can also cause hepatitis, including cytomegalovirus, Epstein-Barr virus, yellow fever, and so forth, although the hepatitis viruses themselves are not all related.

Hepatitis A

Hepatitis A, or infectious jaundice, is caused by a picornovirus (RNA virus). It is transmitted by the feco-oral route—transmitted to humans through contaminated food and water—and can also be transmitted sexually. Hepatitis A can be spread through personal contact, consumption of raw sea food, or drinking contaminated water. This occurs primarily in third world countries.

Hepatitis A causes an acute form of hepatitis that does not have a chronic stage, and carries a 1 percent risk of developing into fulminant hepatitis. The time between the infection and the start of the illness can range from 15 to 45 days, and approximately 15 percent of sufferers may experience relapsing symptoms from six months to a year following initial diagnosis. The patient's immune system makes antibodies against hepatitis A that confer immunity against future infection. Anti-HAV IgM antibodies indicate recent exposure, while Anti-HAV IgG indicate previous exposure and immunity from ever getting the disease in the future.

People with hepatitis A are advised to rest, stay hydrated, and avoid alcohol. An inactivated vaccine is available that will prevent infection from hepatitis A for life and is indicated for those planning to travel to endemic areas as well as those with chronic liver disease. Strict personal hygiene and the avoidance of raw and unpeeled foods can help prevent an infection. Infected persons begin excreting the hepatitis A virus with their stool two weeks after the appearance of the first symptoms.

Hepatitis B

Hepatitis B is caused by a hepadnavirus (virus family Hepadnaviridae, having partially double-stranded, partially single stranded non-circular DNA). This virus can cause both acute and chronic hepatitis. The incubation of the disease varies from 1-6 months. It also accounts for 50 percent of cases of fulminant hepatitis. Chronic hepatitis develops in the 15 percent of patients who are unable to eliminate the virus after an initial infection.

Identified methods of transmission include blood (blood transfusion, now rare), tattoos (both amateur and professionally done), sexually (through sexual intercourse or through contact with blood or bodily fluids such as saliva, synovial fluid, cerebral spinal fluid), in utero (from mother to her unborn child, as the virus can cross the placenta), or through breast milk. However, in about half of cases the source of infection cannot be determined. Blood contact can occur by sharing syringes in intravenous drug use, shaving accessories such as razor blades, or touching wounds of infected persons. Needle-exchange programs have been created in many countries as a form of prevention.

In the United States, 95 percent of patients clear their infection and develop antibodies against hepatitis B virus. Five percent of patients do not clear the infection and develop chronic infection; only these people are at risk of long term complications of hepatitis B.

Patients with chronic hepatitis B have antibodies against hepatitis B, but these antibodies are not enough to clear the infection that establishes itself in the DNA of the affected liver cells. The continued production of virus combined with antibodies is a likely cause of immune-complex disease seen in these patients. Out of these antibodies, the presence of anti-HBs (anti-surface antigen antibody) indicates prior immunity from vaccination; in addition, if anti-HBc (anti-core antigen antibody) is present, it indicates prior infection and immunity. A recombinent HBsAg (surface antigen) vaccine is available that offers 95 percent immunity and is recommended for all newborns, healthcare workers, and people with chronic liver disease. It is included in the national immunization programs of the majority of developed countries and is slowly being incorporated in the developing world.

Hepatitis B infections result in 500,000 to 1,200,000 deaths per year worldwide due to the complications of chronic hepatitis, cirrhosis, and hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatitis B is endemic in a number of (mainly South-East Asian) countries, making cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma big killers. There are three, FDA-approved treatment options available for persons with a chronic hepatitis B infection: Alpha-interferon, adefovir, and lamivudine. In fulminant disease, liver transplantation is the modality for treatment. About 45 percent of persons on treatment achieve a sustained response.

Hepatitis C

Hepatitis C (originally "non-A non-B hepatitis") can be transmitted through contact with blood (major cause of transfusion related hepatitis), sexual contact (much lower than with hepatitis B), as well as in utero. The incubation period of the disease in the body has been found to be 14 days to 6 months. Hepatitis C may lead to a chronic form of hepatitis, culminating in cirrhosis. It can remain asymptomatic for 10-20 years, with only 25 percent of infected patients showing symptoms of the disease. No vaccine is available for hepatitis C. Patients with hepatitis C are prone to severe hepatitis if they contract either hepatitis A or B, so all hepatitis C patients should be immunized against hepatitis A and hepatitis B if they are not already immune. However, hepatitis C itself is a very lethal virus and can cause cirrhosis of the liver. The virus, if detected early on, can be treated by a combination of interferon and the antiviral drug ribavirin. The genotype of the virus determines the rate of response to this treatment regimen.

Hepatitis D

Hepatitis D is an RNA virus that can only exist is the presence of Hepatitis B infection, whether there is superinfection or coinfection. Transmission is commonly seen through blood and blood product transfusion. Patients infected with this virus carry the highest risk of developing fulminant hepatitis and hepatic failure than any other of the viral causes of the disease. There is no vaccine for the prevention of the disease; however, vaccination with hepatitis B vaccine confers immunity for hepatitis D as well.

Hepatitis E

Hepatitis E produces symptoms similar to hepatitis A (also transmitted by the feco-oral route), although it can take a fulminant course in some patients, particularly pregnant women; it is more prevalent on the Indian subcontinent. No vaccine exists for the prevention of this disease.

Hepatitis G

Another type of hepatitis, hepatitis G, has been identified,[1] and is probably spread by blood and sexual contact.[2] There is, however, doubt about whether it causes hepatitis, or is just associated with hepatitis, as it does not appear to be primarily replicated in the liver.[3]

Other viruses

Other viruses can cause infectious hepatitis:

- Mumps virus

- Rubella virus

- Cytomegalovirus

- Epstein-Barr virus

- Other herpes viruses

Alcoholic Hepatitis

Ethanol, mostly in alcoholic beverages, is an important cause of hepatitis. Usually alcoholic hepatitis comes after a period of increased alcohol consumption. Alcoholic hepatitis is characterized by a variable constellation of symptoms, which may include feeling unwell, enlargement of the liver, development of fluid in the abdomen (ascites), and modest elevation of liver blood enzymes. Alcoholic hepatitis can vary from mild, with only liver test elevation, to severe liver inflammation, with development of jaundice, prolonged prothrombin time, and liver failure. Severe cases are characterized by either obtundation (dulled consciousness) or the combination of elevated bilirubin levels and prolonged prothrombin time; the mortality rate in both categories is 50 percent within 30 days of onset.

Alcoholic hepatitis can occur in patients with chronic alcoholic liver disease and alcoholic cirrhosis. A single bout of alcoholic hepatitis by itself does not lead to cirrhosis, but cirrhosis is more common in patients with long term alcohol consumption as repeated bouts of inflammation and subsequent fibrosis lead to cirrhotic state. Patients who drink alcohol to excess are also more often than others found to have hepatitis C. The combination of hepatitis C and alcohol consumption accelerates the development of cirrhosis in Western countries.

Drug induced hepatitis

A large number of drugs can cause hepatitis. The anti-diabetic drug troglitazone was withdrawn in 2000 for causing hepatitis. Other drugs associated with hepatitis:

- Halothane (a specific type of anesthetic gas)

- Methyldopa (antihypertensive drug)

- Isoniazid (INH), rifampicin, and pyrazinamide (tuberculosis-specific antibiotics)

- Phenytoin and valproic acid (antiepileptics)

- Zidovudine (antiretroviral i.e. against AIDS)

- Ketoconazole (antifungal)

- Nifedipine (antihypertensive)

- Ibuprofen and indometacin (NSAIDs)

- Amitriptyline (antidepressant)

- Amiodarone (antiarrhythmic)

- Nitrofurantoin (antibiotic)

- Oral contraceptives

- Allopurinol

- Azathioprine[4]

- Some herbs and nutritional supplements

The clinical course of drug-induced hepatitis is quite variable, depending on the drug and the patient's tendency to react to the drug. For example, halothane hepatitis can range from mild to fatal as can INH-induced hepatitis. Oral contraceptives can cause structural changes in the liver. Amiodarone hepatitis can be untreatable since the long half life (the time needed for the activity of a substance taken into the body to lose 1/2 of its initial effectiveness) of the drug (up to 60 days) means that there is no effective way to stop exposure to the drug. Statins can cause elevations of liver function blood tests normally without indicating an underlying hepatitis. Lastly, human variability is such that any drug can be a cause of hepatitis.

Other toxins that cause hepatitis

Toxins and drugs can cause hepatitis:

- Amatoxin-containing mushrooms, including the Death Cap (Amanita phalloides), the Destroying Angel (Amanita ocreata), and some species of Galerina. A portion of a single mushroom can be enough to be lethal (10 mg or less of α-amanitin).

- Yellow phosphorus, an industrial toxin.

- Paracetamol (acetaminophen in the United States) can cause hepatitis when taken in an overdose. The severity of liver damage can be limited by prompt administration of acetylcysteine.

- Carbon tetrachloride ("tetra," a dry cleaning agent), chloroform, and trichloroethylene, all chlorinated hydrocarbons, cause steatohepatitis (hepatitis with fatty liver).

Metabolic disorders

Some metabolic disorders cause different forms of hepatitis. Hemochromatosis (due to iron accumulation) and Wilson's disease (copper accumulation) can cause liver inflammation and necrosis (cell death).

See below for non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH), effectively a consequence of metabolic syndrome.

Obstructive

"Obstructive jaundice" is the term used to describe jaundice due to obstruction of the bile duct (by gallstones or external obstruction by cancer). If longstanding, it leads to destruction and inflammation of liver tissue.

Autoimmune

Anomalous presentation of human leukocyte antigen (HLA) class II on the surface of hepatocytes—possibly due to genetic predisposition or acute liver infection—causes a cell-mediated immune response against the body's own liver, resulting in autoimmune hepatitis.

Autoimmune hepatitis has an incidence of 1-2 per 100,000 per year, and a prevalence of 15-20/100,000. As with most other autoimmune diseases, it affects women much more often than men (8:1). Liver enzymes are elevated, as is bilirubin. Autoimmune hepatitis can progress to cirrhosis. It is treated with steroids and disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs).

The diagnosis of autoimmune hepatitis is best achieved with a combination of clinical and laboratory findings. A number of specific antibodies found in the blood (antinuclear antibody, smooth muscle antibody, Liver/kidney microsomal antibody , and anti-mitochondrial antibody) are of use, as is finding an increased Immunoglobulin G level. However, the diagnosis of autoimmune hepatitis always requires a liver biopsy. In complex cases, a scoring system can be used to help determine if a patient has autoimmune hepatitis, which combines clinical and laboratory features of a given case.

Four subtypes are recognized, but the clinical utility of distinguishing subtypes is limited.

- Positive ANA and SMA, raised immunoglobulin G (classic form, responds well to low dose steroids)

- Positive LKM-1 (typically female children and teenagers; disease can be severe)

- All antibodies negative, positive antibodies against soluble liver antigen (SLA)(now designated SLP/LP). This group behaves like group 1.

- No autoantibodies detected (~13 percent)

Alpha 1-antitrypsin deficiency

In severe cases of alpha 1-antitrypsin deficiency (A1-AD), the accumulated protein in the endoplasmic reticulum causes liver cell damage and inflammation. This disease may also manifest with panacinar emphysema.

Nonalcoholic steatohepatitis

Non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) is a type of hepatitis which resembles alcoholic hepatitis on liver biopsy (fat droplets, inflammatory cells, but usually no Mallory's hyalin), but occurs in patients who have no known history of alcohol abuse. NASH is more common in women and the most common cause is obesity or the metabolic syndrome. A related but less serious condition is called "fatty liver" (steatosis hepatis), which occurs in up to 80 percent of all clinically obese people. A liver biopsy for fatty liver shows fat droplets throughout the liver, but no signs of inflammation or Mallory's hyalin.

The diagnosis depends on history, physical exam, blood tests, radiological imaging, and sometimes a liver biopsy. The initial evaluation to identify the presence of fatty infiltration of the liver is radiologic imaging including medical ultrasonography (ultrasound), CT scan (computed tomographic imaging), or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). However, radiologic imaging cannot readily identify inflammation in the liver. Therefore, the differentiation between steatosis and NASH often requires a liver biopsy. It can also be difficult to distinguish NASH from alcoholic hepatitis when the patient has a history of alcohol consumption. Sometimes in such cases a trial of abstinence from alcohol along with follow-up blood tests and a repeat liver biopsy are required.

NASH is becoming recognized as the most important cause of liver disease second only to Hepatitis C in numbers of patients going on to cirrhosis.

Hepatitis awareness

World Hepatitis Awareness Day is an annual event organized by several mondial hepatitis advocacy groups to raise awareness of infectious hepatitis, demand action to curb the spread of the disease, and to treat people who are infected. The annual day is held on the first day of October.

Notes

- ↑ J. Linnen et al., Molecular Cloning and Disease Association of Hepatitis G Virus: A Transfusion-Transmissible Agent, Science 271(5248)(1996): 505-508.

- ↑ K Stark, et al., Detection of the Hepatitis G virus genome among injected drug users, homosexual and bisexual men, and blood donors, The Journal of Infectious Diseases 6(174)(1996): 1320-1323.

- ↑ M.G. Pessoa, et al., Quantitation of Hepatitis G and C viruses in the liver: evidence that hepatitis G virus is not hepatotropic, Hepatology, 3(27)(2003): 877-880.

- ↑ G. Bastida, P. Nos, M. Aguas, B. Beltrán, A. Rubín, F. Dasí, and J. Ponce, Incidence, risk factors and clinical course of thiopurine-induced liver injury in patients with inflammatory bowel disease, Aliment Pharmocol Ther, 9(22)(2005): 775-782.

External links

All links retrieved December 19, 2017.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.

↧ Download as ZWI file | Last modified: 02/04/2023 00:26:00 | 11 views

☰ Source: https://www.newworldencyclopedia.org/entry/Hepatitis | License: CC BY-SA 3.0

ZWI signed:

ZWI signed:

KSF

KSF