Frankfurt School

From Nwe

From Nwe

The Frankfurt school is a school of neo-Marxist social theory, social research, and philosophy. The grouping emerged at the Institute for Social Research (Institut für Sozialforschung) of the University of Frankfurt am Main in Germany when Max Horkheimer became the institute's director in 1930. The term "Frankfurt school" is an informal term used to designate the thinkers affiliated with the Institute for Social Research or influenced by them; it is not the title of any institution, and the main thinkers of the Frankfurt school did not use the term to describe themselves.

Frankfurt school theorists were critical of Marx-Leninism and the orthodox interpretation of Marxism, which included ideas of economic determinism, the special role of the communist party, and the role of workers in a communist revolution; totalitarianism and its manifestation in Nazism and communism; and American capitalist mass culture. The theorists of the Frankfurt school thus developed “Western Marxism” based upon ideas taken from Georg Lukács, Sigmund Freud, and Max Weber. Beginning with Horkheimer’s program of “interdisciplinary materialism,” members including Theodor W. Adorno, Walter Benjamin, Herbert Marcuse, Erich Fromm, and Jürgen Habermas applied and developed their studies in diverse social, cultural, historic, and psychoanalytic spheres, resulting in critical theory.

The Frankfurt School can be criticized for its reliance on the atheistic materialist assumptions of Marx and Freud as the foundation for its work. The inherent weakness of that perspective—notably the lack of understanding of the spiritual element of a human being's personal and social life and a one-sided view of the role of religion—limited their framework of interpretation. Yet some of its criticisms of modernity, such as the domination of instrumental reasoning, and the alienation and reification of human life where social relations are dominated by economics, have validity from many perspectives.

Overview

The Frankfurt school gathered together dissident Marxists, severe critics of capitalism who opposed the classical interpretation of Marx's thought in terms of economic determinism and the special role of communist party, usually in defense of orthodox Communist or Social-Democratic parties. Influenced especially by the failure of working-class revolutions in Western Europe after World War I and by the rise of Nazism in an economically, technologically, and culturally advanced nation (Germany), they took up the task of choosing what parts of Marx's thought might serve to clarify social conditions which Marx himself had never seen. They drew on other schools of thought to fill in Marx's perceived omissions. Max Weber exerted a major influence, as did Sigmund Freud (as in Herbert Marcuse's Freudo-Marxist synthesis in the 1954 work Eros and Civilization). Their emphasis on the "critical" component of theory was derived significantly from their attempt to overcome the limits of positivism, crude materialism, and phenomenology by returning to Kant's critical philosophy and its successors in German idealism, principally Hegel's philosophy, with its emphasis on negation and contradiction as inherent properties of reality. A key influence also came from the publication in the 1930s of Marx's Economic and Philosophical Manuscripts of 1844 and The German Ideology, which showed the continuity with Hegelianism that underlay Marx's thought: Marcuse was one of the first to articulate the theoretical significance of these texts.

The First Phase

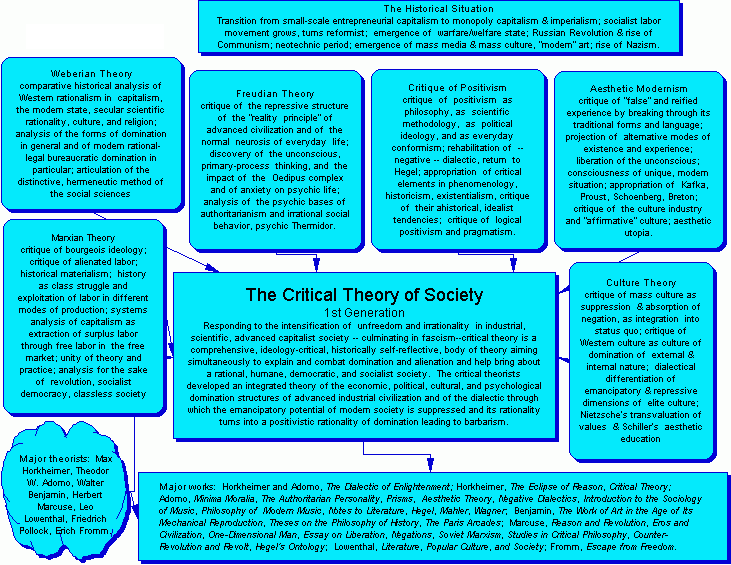

The intellectual influences on and theoretical focus of the first generation of Frankfurt school critical theorists appear in the following diagram:

The institute made major contributions in two areas relating to the possibility of rational human subjects, i.e. individuals who could act rationally to take charge of their own society and their own history. The first consisted of social phenomena previously considered in Marxism as part of the "superstructure" or as ideology: personality, family and authority structures (its first book publication bore the title Studies of Authority and the Family), and the realm of aesthetics and mass culture. Studies saw a common concern here in the ability of capitalism to destroy the preconditions of critical, revolutionary consciousness. This meant arriving at a sophisticated awareness of the depth dimension in which social oppression sustains itself. It also meant the beginning of critical theory's recognition of ideology as part of the foundations of social structure.

The institute and various collaborators had a significant effect on (especially American) social science through their work The Authoritarian Personality, which conducted extensive empirical research, using sociological and psychoanalytic categories, in order to characterize the forces that led individuals to affiliate with or support fascist movements or parties. The study found the assertion of universals, or even truth, to be a hallmark of fascism; by calling into question any notion of a higher ideal, or a shared mission for humanity, The Authoritarian Personality contributed greatly to the emergence of the counterculture.

The nature of Marxism itself formed the second focus of the institute, and in this context the concept of critical theory originated. The term served several purposes—first, it contrasted from traditional notions of theory, which were largely either positivist or scientific. Second, the term allowed them to escape the politically charged label of "Marxism." Third, it explicitly linked them with the "critical philosophy" of Immanuel Kant, where the term "critique" meant philosophical reflection on the limits of claims made for certain kinds of knowledge and a direct connection between such critique and the emphasis on moral autonomy. In an intellectual context defined by dogmatic positivism and scientism on the one hand and dogmatic "scientific socialism" on the other, critical theory meant to rehabilitate through such a philosophically critical approach an orientation toward “revolutionary agency,” or at least its possibility, at a time when it seemed in decline.

Finally, in the context of both Marxist-Leninist and social-democratic orthodoxy, which emphasized Marxism as a new kind of positive science, they were linking up with the implicit epistemology of Karl Marx's work, which presented itself as critique, as in Marx's "Capital: A critique of political economy," wanting to emphasize that Marx was attempting to create a new kind of critical analysis oriented toward the unity of theory and revolutionary practice rather than a new kind of positive science. In the 1960s, Jürgen Habermas raised the epistemological discussion to a new level in his "Knowledge and Human Interests" (1968), by identifying critical knowledge as based on principles that differentiated it either from the natural sciences or the humanities, through its orientation to self-reflection and emancipation.

Although Horkheimer's distinction between traditional and critical theory in one sense merely repeated Marx's dictum that philosophers have always interpreted the world and the point is to change it, the Institute, in its critique of ideology, took on such philosophical currents as positivism, phenomenology, existentialism, and pragmatism, with an implied critique of contemporary Marxism, which had turned dialectics into an alternate science or metaphysics. The institute attempted to reformulate dialectics as a concrete method, continually aware of the specific social roots of thought and of the specific constellation of forces that affected the possibility of liberation. Accordingly, critical theory rejected the materialist metaphysics of orthodox Marxism. For Horkheimer and his associates, materialism meant the orientation of theory towards practice and towards the fulfillment of human needs, not a metaphysical statement about the nature of reality.

The Second Phase

The second phase of Frankfurt school critical theory centers principally on two works that rank as classics of twentieth-century thought: Horkheimer's and Adorno's Dialectic of Enlightenment (1944) and Adorno's Minima Moralia (1951). The authors wrote both works during the institute's American exile in the Nazi period. While retaining much of the Marxian analysis, in these works critical theory has shifted its emphasis. The critique of capitalism has turned into a critique of Western civilization as a whole. Indeed, the Dialectic of Enlightenment uses the Odyssey as a paradigm for the analysis of bourgeois consciousness. Horkheimer and Adorno already present in these works many themes that have come to dominate the social thought of recent years. For example, the domination of nature appears as central to Western civilization long before ecology had become a catchphrase of the day.

The analysis of reason now goes one stage further. The rationality of Western civilization appears as a fusion of domination and of technological rationality, bringing all of external and internal nature under the power of the human subject. In the process, however, the subject itself gets swallowed up, and no social force analogous to the “proletariat” can be identified that will enable the subject to emancipate itself. Hence the subtitle of Minima Moralia: "Reflections from Damaged Life." In Adorno's words,

For since the overwhelming objectivity of historical movement in its present phase consists so far only in the dissolution of the subject, without yet giving rise to a new one, individual experience necessarily bases itself on the old subject, now historically condemned, which is still for-itself, but no longer in-itself. The subject still feels sure of its autonomy, but the nullity demonstrated to subjects by the concentration camp is already overtaking the form of subjectivity itself.

Consequently, at a time when it appears that reality itself has become ideology, the greatest contribution that critical theory can make is to explore the dialectical contradictions of individual subjective experience on the one hand, and to preserve the truth of theory on the other. Even the dialectic can become a means to domination: "Its truth or untruth, therefore, is not inherent in the method itself, but in its intention in the historical process." And this intention must be toward integral freedom and happiness: "the only philosophy which can be responsibly practiced in face of despair is the attempt to contemplate all things as they would present themselves from the standpoint of redemption." How far from orthodox Marxism is Adorno's conclusion: "But beside the demand thus placed on thought, the question of the reality or unreality of redemption itself hardly matters."

Adorno, a trained musician, wrote The Philosophy of Modern Music, in which he, in essence, polemicizes against beauty itself—because it has become part of the ideology of advanced capitalist society and the false consciousness that contributes to domination by prettifying it. Avant-garde art and music preserve the truth by capturing the reality of human suffering. Hence:

What radical music perceives is the untransfigured suffering of man... The seismographic registration of traumatic shock becomes, at the same time, the technical structural law of music. It forbids continuity and development. Musical language is polarized according to its extreme; towards gestures of shock resembling bodily convulsions on the one hand, and on the other towards a crystalline standstill of a human being whom anxiety causes to freeze in her tracks... Modern music sees absolute oblivion as its goal. It is the surviving message of despair from the shipwrecked.

This view of modern art as producing truth only through the negation of traditional aesthetic form and traditional norms of beauty because they have become ideological is characteristic of Adorno and of the Frankfurt school generally. It has been criticized by those who do not share its conception of modern society as a false totality that renders obsolete traditional conceptions and images of beauty and harmony.

The Third Phase

From these thoughts only a short step remained to the third phase of the Frankfurt school, which coincided with the post-war period, particularly from the early 1950s to the middle 1960s. With the growth of advanced industrial society under Cold War conditions, the critical theorists recognized that the structure of capitalism and history had changed decisively, that the modes of oppression operated differently, and that the industrial “working class” no longer remained the determinate negation of capitalism. This led to the attempt to root the dialectic in an absolute method of negativity, as in Marcuse's One-Dimensional Man and Adorno's Negative Dialectics. During this period the Institute of Social Research resettled in Frankfurt (although many of its associates remained in the United States) with the task not merely of continuing its research but of becoming a leading force in the sociological education and “democratization” of West Germany. This led to a certain systematization of the institute's entire accumulation of empirical research and theoretical analysis.

More importantly, however, the Frankfurt school attempted to define the fate of reason in the new historical period. While Marcuse did so through analysis of structural changes in the labor process under capitalism and inherent features of the methodology of science, Horkheimer and Adorno concentrated on a re-examination of the foundation of critical theory. This effort appears in systematized form in Adorno's Negative Dialectics, which tries to redefine dialectics for an era in which "philosophy, which once seemed obsolete, lives on because the moment to realize it was missed."

Negative dialectics expresses the idea of critical thought so conceived that the apparatus of domination cannot co-opt it. Its central notion, long a focal one for Horkheimer and Adorno, suggests that the original sin of thought lies in its attempt to eliminate all that is other than thought, the attempt by the subject to devour the object, the striving for identity. This reduction makes thought the accomplice of domination. Negative Dialectics rescues the "preponderance of the object," not through a naive epistemological or metaphysical realism but through a thought based on differentiation, paradox, and ruse: a "logic of disintegration." Adorno thoroughly criticizes Martin Heidegger's fundamental ontology, which reintroduces idealistic and identity-based concepts under the guise of having overcome the philosophical tradition.

Negative Dialectics comprises a monument to the end of the tradition of the individual subject as the locus of criticism. Without a revolutionary working class, the Frankfurt school had no one to rely on but the individual subject. But, as the liberal capitalist social basis of the autonomous individual receded into the past, the dialectic based on it became more and more abstract. This stance helped prepare the way for the fourth, current phase of the Frankfurt school, shaped by the communication theory of Habermas.

Habermas' work takes the Frankfurt school's abiding interests in rationality, the human subject, democratic socialism, and the dialectical method and overcomes a set of contradictions that always weakened critical theory: the contradictions between the materialist and transcendental methods, between Marxian social theory and the individualist assumptions of critical rationalism between technical and social rationalization, and between cultural and psychological phenomena on the one hand and the economic structure of society on the other. The Frankfurt school avoided taking a stand on the precise relationship between the materialist and transcendental methods, which led to ambiguity in their writings and confusion among their readers. Habermas' epistemology synthesizes these two traditions by showing that phenomenological and transcendental analysis can be subsumed under a materialist theory of social evolution, while the materialist theory makes sense only as part of a quasi-transcendental theory of emancipatory knowledge that is the self-reflection of cultural evolution. The simultaneously empirical and transcendental nature of emancipatory knowledge becomes the foundation stone of critical theory.

By locating the conditions of rationality in the social structure of language use, Habermas moves the locus of rationality from the autonomous subject to subjects in interaction. Rationality is a property not of individuals per se, but rather of structures of undistorted communication. In this notion Habermas has overcome the ambiguous plight of the subject in critical theory. If capitalistic technological society weakens the autonomy and rationality of the subject, it is not through the domination of the individual by the apparatus but through technological rationality supplanting a describable rationality of communication. And, in his sketch of communicative ethics as the highest stage in the internal logic of the evolution of ethical systems, Habermas hints at the source of a new political practice that incorporates the imperatives of evolutionary rationality.

Frankfurt school critical theory has influenced some segments of the left-wing and leftist thought (particularly the New Left). Frankfurt school theorists have occasionally been described as the theorist or intellectual progenitor of the New Left. Their work also heavily influenced intellectual discourse on popular culture and scholarly popular culture studies.

Critics of the Frankfurt school

Several camps of criticism of the Frankfurt school have emerged.

- The theoretical assumptions of Marx and Freud had inherent problems, including the lack of understanding of the spiritual element, which limited their framework of interpretation.

- Although Frankfurt theorists delivered a number of criticisms against the theories and practices of their days, they did not present any positive alternatives.

- The intellectual perspective of the Frankfurt school is really a romantic, elitist critique of mass culture dressed-up in neo-Marxist clothing: what really bothers the critical theorists in this view is not social oppression, but that the masses like Ian Fleming and The Beatles instead of Samuel Beckett and Anton Webern. Adorno’s high esteem for the high arts and severe criticism of jazz was one example.

- Another criticism, originating from the left, is that critical theory is a form of bourgeois idealism that has no inherent relation to political practice and is totally isolated from any ongoing revolutionary movement.

- Criticisms to their pedantic elitism were captured in Georg Lukács's phrase "Grand Hotel Abyss" as a syndrome he imputed to the members of the Frankfurt school.

A considerable part of the leading German intelligentsia, including Adorno, have taken up residence in the ‘Grand Hotel Abyss’ which I described in connection with my critique of Schopenhauer as ‘a beautiful hotel, equipped with every comfort, on the edge of an abyss, of nothingness, of absurdity. And the daily contemplation of the abyss between excellent meals or artistic entertainments, can only heighten the enjoyment of the subtle comforts offered.[1]

- Notable critics of the Frankfurt school

-

- Henryk Grossman

- Georg Lukács

- Umberto Eco

Major Frankfurt school thinkers and scholars

- Theodor W. Adorno

- Max Horkheimer

- Walter Benjamin

- Herbert Marcuse

- Alfred Sohn-Rethel

- Leo Löwenthal

- Franz Leopold Neumann

- Franz Oppenheimer

- Friedrich Pollock

- Erich Fromm

- Alfred Schmidt

- Jürgen Habermas

- Oskar Negt

- Karl A. Wittfogel

- Susan Buck-Morss

- Axel Honneth

Notes

- ↑ Georg Lukács, Preface to The Theory of the Novel (1962) Retrieved July 6, 2007.

References

ISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Arato, Andrew and Eike Gebhardt. The Essential Frankfurt School Reader. Continuum International Publishing Group, 1982. ISBN 0826401945

- Martin, Jay. The Dialectical Imagination: A History of the Frankfurt School and the Institute for Social Research 1923-1950. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 1996. ISBN 0520204232

- Mendieta, Eduar. The Frankfurt School on Religion. London: Routledge, 2004. ISBN 0415966965

- Shapiro, Jeremy J. "The Critical Theory of Frankfurt," Times Literary Supplement (Oct. 4, 1974, No. 3): 787. (Material from this publication has been used or adapted for the present article with permission.)

- Wiggershaus, Rolf. The Frankfurt School: Its History, Theories and Political Significance. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 1995. ISBN 0262731134

External links

All links retrieved May 8, 2017.

- Institute for Social Research

- The Frankfurt School (Marxists Internet Archive)

- Excerpts from "Eros and Civilization"

General Philosophy Sources

- Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy

- The Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy

- Paideia Project Online

- Project Gutenberg

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.

↧ Download as ZWI file | Last modified: 02/04/2023 02:32:07 | 158 views

☰ Source: https://www.newworldencyclopedia.org/entry/Frankfurt_School | License: CC BY-SA 3.0

ZWI signed:

ZWI signed:

KSF

KSF