Alexander I Of Yugoslavia

From Nwe

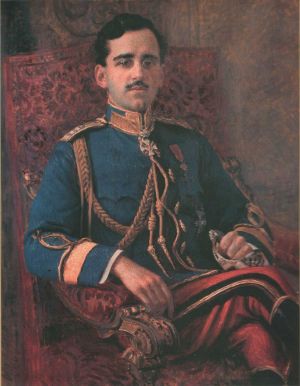

From Nwe Alexander I also called Alexander I Karađorđević or Alexander the Unifier Serbian, Croatian, Serbo-Croatian: Aleksandar I Karađorđević, Cyrillic script: Александар I Карађорђевић) (Cetinje, Principality of Montenegro, December 4/December 16 1888 – Marseille, France, October 9, 1934) of the Royal House of Karađorđević (Karageorgevich) was the first king of Yugoslavia (1929–34) and before that the second monarch of the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes (1921–1929). He had acted as regent of Serbia since June 24, 1914. Before succeeding his father as king, he distinguished himself in military service and was supreme commander of the Serbian army during World War I. Throughout his reign, Alexander exercised wide ranging powers. From 1918 until 1929 his power was shared with an elected assembly. However, faced with separatist movements in Croatia and Macedonia, he assumed dictatorial authority in 1929. He changed the name of the kingdom to Yugoslavia, attempting to suppress provincial and separatist sentiment by creating a strong unitary state with a single national identity. He is often described as a Fascist. Opposition politicians were arrested as insurgency and counter-insurgency destabilized the state. One of Alexander's principal concerns was to retain the favor of the great powers. In October 1934 he was visiting France, an important ally, when dissidents assassinated him. Caught on camera, the footage is of considerable historical interest.

The logic of Yugoslavia was that a unified Balkan state could maximize resources and defend itself from potential external threats. However, the state was from the outset dominated by the Serbian dream of reviving their medieval dominance in the region at the expense of the autonomy of other ethnicities. What was meant to be a union became a takeover. Alexander's own dictatorial style and centralization of power provided a pattern that later rulers followed, including Josip Broz Tito who ruled with an iron fist from 1945 until 1980. After his death, Yugoslavia began to implode. Some argue that Yugoslavia's disintegration discredits the Federal option for holding different nationalities in balance. However, it can be countered that what went wrong in Yugoslavia, from the very beginning of Alexander's reign to the end of Tito's rule, was failure to achieve a fair and reasonable balance between provincial autonomy and the federal center, or to establish an effective power-sharing, consociational democracy. If Alexander had turned to negotiation to work out a compromise between local and central authority, Yugoslavia may have survived intact. Many of Alexander's advisers were committed to the notion of Greater Serbia; his personal instincts may have favored compromise and improved inter-ethnic relations. Alexander was too concerned with his own position to act in the best interests of his subjects. The move by former Yugoslav republics to join the European Union shows that they are not adverse to belonging to a "union" based on cooperative principles, social justice and respect for diversity.

Childhood

Alexander Karađorđević was born in Cetinje in Principality of Montenegro in December 1888. His father was King Peter I of Serbia and his mother the former Princess Zorka of Montenegro, a daughter of King Nicholas of Montenegro. In Belgrade on June 8, 1922 he married HRH Princess Maria of Romania, who was a daughter of Queen Maria, the Queen Consort of Romania. They had three sons: Crown Prince Peter, Princes Tomislav and Andrej.

He spent his childhood in Montenegro, and was educated in Geneva. In 1910 he nearly died from stomach typhus and left with stomach problems for rest of his life. He continued his schooling at the Corps de pages imperial in Saint Petersburg, Russia, but had to quit due to his brother's renunciation, and then in Belgrade. Prince Alexander was not the first in line for the throne but his elder brother, Crown Prince George (Đorđe) was considered unstable by most political forces in Serbia and after two notable scandals (one of which occurred in 1909 when he kicked his servant, who consequently died), Prince George was forced to renounce his claim to the throne.

Creation of Yugoslavia

After centuries of Ottoman domination, various Balkan provinces began to emerge as independent states in the late nineteenth century. In 1878, the Congress of Berlin recognized Serbia and Montenegro although it placed Bosnia and Herzegovina under Austria-Hungary. Croatia and Slovenia were already within the Austro-Hungaraian empire. Croatia and Slovenia were demanding independence; some Croats, as were some Serbs, were advocating the creation of a large South Slav state. This would help protect the Balkans from outside powers; at this point Italy was perceived to have ambitions in the region. Serbia lost her traditional ally, Russia after the Russian Revolution of 1917.

When the Austro-Hungarian empire was dissolved following World War I, Croatia, Slovenia and Bosnia-Herzegovina and when, after the First Balkan War (1912-1913) Macedonia was liberated from Ottoman rule, all these Balkan states were ready to unite as the Kingdom of the Slovenes, Croats, and Serbs. For Serbs especially, this was regarded as a revival of the medieval Serbian empire that had once dominated the Balkans.

They united under the rule of the Serbian prince, Peter. Peter ruled from December 1, 1918 – August 16, 1921, when Alexander succeeded him. The new state was born and created despite competing political visions; the Croats wanted strong provincial governments and a weak federal government; Serbs wanted a strong unitary state, effectively a Greater Serbia. The reality was that the Kingdom would be dominated by Serbs. Power was shared between the king and an elected assembly but the latter only considered legislation that had already been drafted and had no role in foreign affairs.

Balkan Wars and World War I

In the First Balkan War in 1912, as commander of the First Army, Crown Prince Alexander fought victorious battles in Kumanovo and Bitola, and later in 1913, during the Second Balkan War, the battle of Bregalnica. In the aftermath of the Second Balkan War Prince Alexander took sides in the complicated power struggle over how Macedonia should be administered. In this Alexander bested Col. Dragutin Dimitrijević or "Apis" and in the wake of this Alexander's father, King Peter, agreed to hand over royal powers to his son. On June 24, 1914 Alexander became Regent of Serbia.

At the outbreak of World War I he was the nominal supreme commander of the Serbian army—true command was in hands of Chief of Staff of Supreme Headquarters—position held by Stepa Stepanović (during the mobilization), Radomir Putnik (1914-1915), Petar Bojović (1916-1917) and Živojin Mišić (1918). The Serbian army distinguished itself in the battles at Cer and at the Drina (the Battle of Kolubara) in 1914 , scoring victories against the invading Austro-Hungarian forces and evicting them from the country.

In 1915 the Serbian army with the aged King Peter and Crown Prince Alexander suffered many losses being attacked from all directions by the alliance of Germany, Austria-Hungary and Bulgaria. It withdrew through the gorges of Montenegro and northern Albania to the Greek island of Corfu, where it was reorganized. After the army was regrouped and reinforced, it achieved a decisive victory on the Macedonian Front, at Kajmakcalan. The Serbian army carried out a major part in the final Allied breakthrough in the autumn of 1918.

King of Yugoslavia

On December 1, 1918, in a prearranged set piece, Alexander, as Regent, received a delegation of the People's Council of the State of Slovenes, Croats and Serbs, an address was read out by one of the delegation, and Alexander made an address in acceptance. This was considered to be the birth of the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes.

In 1921, on the death of his father, Alexander inherited the throne of the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes, which from its inception was colloquially known both in the Kingdom and the rest of Europe alike as Yugoslavia. Tension continued between Serbs and Croats within the political process. In 1928, the Croat Ustaše party was formed, which campaigned for independence. The Croatian Peasant Party under Stjepan Radić boycotted parliament for several years. However, on June 20, 1928 after Radić actually won a plurality of seats but was blocked from forming the government, he was shot and mortally wounded by a Serb deputy, Puniša Račić while attending the Assembly.

On January 6, 1929, in response to the political crisis triggered by Radić's death (he died on August 8), King Alexander abolished the Constitution, prorogued the Parliament and introduced a personal dictatorship (the so-called "January 6 Dictatorship," Šestojanuarska diktatura). He also changed the name of the country to Kingdom of Yugoslavia and reorganized the internal divisions from the 33 oblasts to nine new banovinas on October 3. These were named after rivers in an attempt o "wipe out the memory of ethnic divisions."[1] Alexander is typically described as a dictator although he relied heavily on Petar Živković, whom he appointed as Prime Minister. It was even rumored that the two men were lovers.[2] Glenny says that Alexander was prone to temper tantrums and was well aware of the profound challenge that Serb-Croat relations presented.[3] Glenny says that Alexander thought the privileging of Serbs justified since in his view it was Serbs who had made the kingdom possible by their successes in the Balkans Wars; "Yugoslavia, he was convinced, owed its existence to the heroism of the Serbian army in the Balkan Wars." Yet, in contrast to the shallow Greater Serbian counselors who surrounded him," he "developed an appreciation and even and admiration for the Croats and Slovenes during the late 1920s and early 1930s."[4] The name Yugoslavia like those of the new districts was meant to nurture a new, single national identity.

In the same month, he tried to banish by decree the use of Serbian Cyrillic to promote the exclusive use of Latin alphabet in Yugoslavia.[5]

In 1931, Alexander decreed a new Constitution which transferred executive power to the King. Elections were to be by universal male suffrage. The provision for a secret ballot was dropped and pressure on public employees to vote for the governing party was to be a feature of all elections held under Alexander's constitution. Furthermore, the King would appoint half the upper house directly, and legislation could become law with the approval of one of the houses alone if it were also approved by the King. Payne argues that Alexander's attempt to create a unified state and to elevate the state over all other identities was inspired by Fascism but that he "failed to develop an ideology or political organization" as did other Fascist leaders.[6] Alexander was especially keen to impress on the European powers that Yugoslavia was "stable," since when Yugoslavia appeared to be unstable this "invariably provoked diplomatic flurries in and between Paris, London, Rome and Berlin."[2] The situation continued to deteriorate, however, as Croats began a "bombing and shooting campaign" and Alexander responded by "arresting leading members of most political parties in Croatia."[7]

Assassination

On account of the deaths of three members of his family on a Tuesday, Alexander refused to undertake any public functions on that day. On Tuesday October 9, 1934, however, he had no choice, as he was arriving in Marseille to start a state visit to the Third French Republic, to strengthen the two countries' alliance in the Little Entente. While being driven in a car through the streets along with French Foreign Minister Louis Barthou, a gunman, Vlado Chernozemski, stepped from the street and shot the King and the chauffeur. The Minister was accidentally shot by a French policeman and died later.

It was one of the first assassinations captured on film; the shooting occurred straight in front of the cameraman, who was only feet away at the time. The cameraman captured not merely the assassination but the immediate aftermath; the body of the chauffeur (who had been killed instantly) became jammed against the brakes of the car, allowing the cameraman to continue filming from within inches of the King for a number of minutes afterwards.

The assassin, Vlado Chernozemski — driver of the leader of the Internal Macedonian Revolutionary Organization (IMRO) Ivan Mihailov and an experienced marksman—was cut down by the sword of a mounted French policeman, then beaten by the crowd. By the time he was removed from the scene, he was already dead. The IMRO was a Bulgarian political organization that fought for annexing Macedonia to Bulgaria using terrorist means. According to the UKTV History program Infamous Assassinations-King Alexander, the organization worked in alliance with the Ustaše fascist, under the secret sponsorship of Italian dictator Benito Mussolini.

The film record of Alexander I's assassination remains one of the most notable pieces of newsreel in existence,[8] alongside the film of Tsar Nicholas II of Russia's coronation, the funerals of Queen Victoria of the United Kingdom and Emperor Franz Josef of Austria, and the assassination of John F. Kennedy. Glenny discusses the possibility of Italian complicity in the assassination. Many Croats had found asylum in Italy where Ante Pavelić was running the paramilitary wing of the Ustaše which made common cause with the Macedonian Revolutionary Organization.[9] On the other hand, Alexander had entered secret talks with Mussolini due to French pressure to mend relations with Italy.[10] However, he broke off contact in December 1933 when he discovered an assassination plot.[11] While there is no "conclusive evidence of Italian government involvement, Rome had made no attempt to curb Ustaše terrorism."[12]

Burial

King Alexander I was buried in the Memorial Church of St. George, which had been built by his father. As his son Peter II was still a minor, Alexander's first cousin Prince Pavle Karadjordjevic took the regency of the Kingdom of Yugoslavia.

Legacy

Payne says that Alexander's assassination resulted in a return to a milder political climate in Yugoslavia and that by 1939 the "regime had returned to a kind of political pluralism."[13] However, the policy of suppressing the national identities of the various ethnic groups that constituted Yugoslavia continued under the post-World War II communist dictator, Josip Broz Tito. Unfortunately, Yugoslavia imploded following Tito's death, when one by one all provinces emerged as independent states after much bloodshed and Serbian refusal to surrender the dream of a Greater Serbia. The failure of such multicultural states as Yugoslavia has led some, among others, Samuel P Huntington to argue that multicultural states are weak and undesirable, that only states with a strong dominant culture can thrive. "History shows" wrote Huntington, that no country so constituted can long endure as a coherent society."[14] Others argue that Yugoslavia's disintegration discredits the Federal option for holding different nationalities in balance. Others, however, point to Switzerland as an enduring and successful example of a multicultural state, arguing that what went wrong in Yugoslavia was failure to achieve a fair and reasonable balance between provincial autonomy and the federal center, or to establish an effective power-sharing, consociationalism democracy.[15]

Alexander's style of kingly dictatorship may have influenced the Romanian king, Carol II who issued a new constitution that concentrated power in his own hand in 1938.[16] Alexander did not give democracy a chance; he was too anxious to maintain his own authority at the center. Glenny says that on the one hand he was "gifted with real political intelligence" but on the other "his psychological insecurity guaranteed the regular commission of errors."[2] Živković "knew how to exploit his weakness" and his appointment as Prime Minister "was greeted with undisguised dismay not only by Croats but in Serbia, Slovenia, Bosnia and Montenegro." It was widely whispered that with a man such as Živković in charge "there was little prospect of the king solving Yugoslavia's political crises."[2] Instead of negotiation and compromise, the king responded with the heavy hand of oppression. Alexander's intent may well have been to maintain stability and a strong, united state but his acts were those of a tyrant. His own intent may have been towards improved relations between the different nationalities but he chose advisers whose acts were motivated by their dreams of Greater Serbia. In the end, however, Alexander was too concerned with his own position to act in the best interests of his subjects.

Ancestors

| Alexander I of Yugoslavia | Father: Peter I of Yugoslavia |

Paternal Grandfather: Alexander Karađorđević, Prince of Serbia |

Paternal Great-grandfather: Karađorđe Petrović |

| Paternal Great-grandmother: Jelena Jovanovic |

|||

| Paternal Grandmother: Persida Nenadović |

Paternal Great-grandfather: Jevrem Nenadović |

||

| Paternal Great-grandmother: |

|||

| Mother: Zorka of Montenegro |

Maternal Grandfather: Nicholas I of Montenegro |

Maternal Great-grandfather: Mirko Petrović Njegoš |

|

| Maternal Great-grandmother: Anastasija Martinović |

|||

| Maternal Grandmother: Milena Vukotić |

Maternal Great-grandfather: Petar Vukotić |

||

| Maternal Great-grandmother: Jelena Voivodić |

| House of Karađorđević Born: December 16 1888; Died: October 9 1934 |

||

|---|---|---|

| Regnal Titles |

||

| Preceded by: Peter I as King of Serbs, Croats, and Slovenes |

King of the Serbs, Croats, and Slovenes August 16, 1921 - January 6, 1929 |

Succeeded by: Proclaimed King of Yugoslavia |

| New Title | King of Yugoslavia January 6, 1929 - October 9, 1934 |

Succeeded by: Peter II |

Notes

- ↑ Mousavizadeh 1996, 14.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 Glenny 2000, 429.

- ↑ Glenny 2000, 429-430.

- ↑ Glenny 2000, 430.

- ↑ Dangerous Decree. Time/CNN. Retrieved February 21, 2009.

- ↑ Payne 1995, 114.

- ↑ Glenny 2000, 432.

- ↑ The Assassination and the Funeral of the Yugoslavian king Alexander in 1934. Manrigue, Rody Green, Kenneth Upton, Teddy Rickman, L. Korenman, Charles Mack, Thomas Bills, et al. 1934. Hearst Metrotone news. Vol. 6, no. 208. United States: Distributed by Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer. Retrieved February 21, 2009.

- ↑ Glenny 2000, 431.

- ↑ Glenny 2000, 434.

- ↑ Glenny 2000, 434-435.

- ↑ Glenny 2000, 435.

- ↑ Payne 1995, 144.

- ↑ Huntington 1996, 306.

- ↑ Mario Apostolov, 2004, The Christian-Muslim frontier a zone of contact, conflict, or cooperation. (London, UK: RoutledgeCurzon. ISBN 9780203493861), 147.

- ↑ Payne 1995, 288.

References

ISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Glenny, Misha. 2000. The Balkans: Nationalism, War, and the Great Powers, 1804-1999. New York, NY: Viking. ISBN 9780670853380.

- Graham, Stephen. 1972. Alexander of Yugoslavia; the Story of the King Who Was Murdered at Marseilles. Hamden, CT: Archon Books. ISBN 9780208010827.

- Huntington, Samuel P. 1996. The Clash of Civilizations and the Remaking of World Order. New York, NY: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 9780684811642.

- Mousavizadeh, Nader. 1996. The Black Book of Bosnia: the Consequences of Appeasement. New York, NY: BasicBooks. ISBN 9780465098354.

- Payne, Stanley G. 1995. A History of Fascism, 1914-1945. Madison, WI: University of Wisconsin Press. ISBN 9780299148706.

- Roberts, Allen. 1970. The Turning Point: the Assassination of Louis Barthou and King Alexander I of Yugoslavia. New York, NY: St. Martin's Press.

External links

All links retrieved May 15, 2021.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.

↧ Download as ZWI file | Last modified: 02/03/2023 21:51:00 | 175 views

☰ Source: https://www.newworldencyclopedia.org/entry/Alexander_I_of_Yugoslavia | License: CC BY-SA 3.0

ZWI signed:

ZWI signed:

KSF

KSF