Rabindranath Tagore

From Nwe

From Nwe

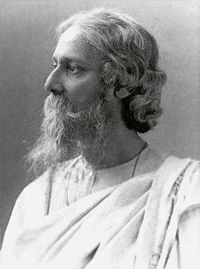

Rabindranath Tagore (May 7, 1861 - August 7, 1941), known also as Gurudev, was a Bengali poet, philosopher, religious thinker and intellectual leader, artist, playwright, composer, educationalist and novelist whose works reshaped Bengali literature and music in the late ninteenth and early twentieth centuries. A celebrated cultural icon in India, he became Asia's first Nobel laureate when he won the 1913 Nobel Prize in Literature. He is regarded as a towering cultural figure in all Bengali-speaking regions.

Tagore was born in Jorasanko, Kolkata (formerly known as Calcutta), which became part of post-independence India. A Brahmin by birth, Tagore began writing poems at the age of eight; he published his first substantial poetry—using the pseudonym "Bhānusiṃha" ("Sun Lion") at age sixteen, in 1877. Later that year he wrote his first short stories and dramas. His home schooling, life in Shelidah, and extensive travels made Tagore an iconoclast and pragmatist. However, growing disillusionment with the British Raj caused Tagore to back the Indian Independence Movement and befriend M. K. Gandhi. It was Tagore who bestowed the title “Mahamta” (Great Spirit), which testifies to the status he himself enjoyed as a religious and intellectual leader, although like Gandhi, he never held elected or public office. In response, Gandhi called Tagore “the great Sentinel.”

Knighted in 1915, Tagore renounced using the title 'Sir' in 1919 following the massacre at Amritsar. Despite the loss of almost his entire family and his regrets regarding Bengal's decline, his life's work—Visva-Bharati University—endured. In Bengali, he is known as the “universal poet.” Hindus regard him as a universalist. He described his own family as a “confluence of three cultures” (Hindu, Muslim, and British). He disliked separatism, preferring convergence (1931: 105). He rejected militarism and nationalism. Instead, he promoted spiritual values and to construct a new world civilization permeated by tolerance, which would draw on the best of all cultures. The school he founded combined Western and Eastern practices. He is best known as someone who always wanted to build bridges, not barriers. Tagore favored a religion of humanity (Manusher Dhormo). His poems demonstrate a reverence for nature, with which he believed humanity should enjoy a harmonious—not exploitative—relationship. Nature, for him, was divine—as is the human soul. He could write for both children and for adults.

Tagore's major works included Gitanjali (“Song Offerings” [1] - there are two versions, English and Bengali, which are not identical), Gora (“Fair-Faced”), and Ghare-Baire (“The Home and the World”), while his verse, short stories, and novels—many defined by rhythmic lyricism, colloquial language, meditative and philosophical contemplation—received worldwide acclaim. Tagore was also a cultural reformer and polymath who modernized Bangla art by rejecting strictures binding it to classical Indian forms. Two songs from his rabindrasangit canon are now the national anthems of Bangladesh and India: the Amar Shonar Bangla and the Jana Gana Mana.

Early life (1861–1901)

Tagore (nicknamed "Rabi") was born the youngest of fourteen children in the Jorasanko mansion of parents Debendranath Tagore (1817-1905) and Sarada Devi. His father, known as the Great Sage, was a prominent Hindu reformer and a leader of the Brahmo Samaj. After undergoing his upanayan (coming-of-age) rite at age eleven, Tagore and his father left Calcutta on February 14, 1873 to tour India for several months, visiting his father's Santiniketan estate and Amritsar before reaching the Himalayan hill station of Dalhousie. There, Tagore read biographies, studied history, astronomy, modern science, and Sanskrit, and examined the classical poetry of (Dutta and Robinson 1995, 55-56; Stewart and Twichell 2003, 91). In 1877, he arose to notability when he composed several works, including a long poem set in the Maithili style pioneered by Vidyapati (1374-1460). As a joke, he initially claimed that these were the lost works of what he claimed to be a newly discovered seventeenth-century 'Vaishnavite poet called Bhānusiṃha (Stewart and Twichell 2003, 3). He also wrote Bhikharini (1877; "The Beggar Woman"—the Bangla language's first short story) (Chakravarty 1961, 45; Dutta and Robinson 1997, 265) and Sandhya Sangit (1882)—including the famous poem "Nirjharer Swapnabhanga" ("The Rousing of the Waterfall").

Planning on becoming a barrister, Tagore enrolled at a public school in Brighton, England in 1878. Later, he studied at University College, London, but returned to Bengal in 1880 without a degree, because his father had arranged a marriage for him. On December 9, 1883, he married ten-year-old Mrinalini Devi; they had five children, four of whom later died before reaching full adulthood (Dutta and Robinson 1995, 373). He had a great love of children. Several granddaughters, including Sushanta, who managed his estate and Nandita Kriplani, a founder trustee of the Indian National Theater, survived him. In 1890, Tagore (joined in 1898 by his wife and children) began managing his family's estates in Shelidah, a region now in Bangladesh. Known as Zamindar Babu (land-owner, almost like the English ‘squire’), Tagore traveled across the vast estate while living out of the family's luxurious barge, the Padma, to collect (mostly token) rents and bless villagers; in exchange, he had feasts held in his honor (Dutta and Robinson 1995, 109-111). During these years, Tagore's Sadhana period (1891–1895; named for one of Tagore’s magazines) was among his most productive, writing more than half the stories of the three-volume and eighty-four-story Galpaguchchha (Chakravarty 1961, 45}. With irony and emotional weight, they depicted a wide range of Bengali lifestyles, particularly village life (Dutta and Robinson 1995, 109}.

Santiniketan (1901–1932)

In 1901, Tagore left Shelidah and moved to Santiniketan (West Bengal) to found an ashram, which would grow to include a marble-floored prayer hall ("The Mandir") (Temple), an experimental school, groves of trees, gardens, and a library (Dutta and Robinson 1995, 133}. There, Tagore's wife and two of his children died. His father also died on January 19, 1905, and he began receiving monthly payments as part of his inheritance; he also received income from the Maharaja of Tripura, sales of his family's jewelry, his seaside bungalow in Puri, Orissa, and mediocre royalties (Rs. 2,000) from his works (139-140).

These works gained him a large following among Bengali and foreign readers alike, and he published such works as Naivedya (1901) and Kheya (1906) while translating his poems into free verse. On November 14, 1913, Tagore learned that he had won the 1913 Nobel Prize in Literature. According to the Swedish Academy, it was given due to the idealistic and—for Western readers—accessible nature of a small body of his translated material, including the 1912 Gitanjali: Song Offerings (Hjärne 1913}. In addition, Tagore was knighted by the British Crown in 1915. In 1919, he renounced the title 'sir' following the massacre at Amritsar, which cost the British what justification they had for perpetuating their rule in India.

In 1921, Tagore and agricultural economist Leonard Elmhirst (1893-1974) set up the Institute for Rural Reconstruction (which Tagore later renamed Shriniketan—"Abode of Peace") in Surul, a village near the ashram at Santiniketan. He is credited with founding rural reconstruction in India. He worked with the farmer to identify problems and to find solutions by experimenting on his community farm. Through his ashram, Tagore sought to provide an alternative to Gandhi's symbol- and protest-based Swaraj (self-rule) movement, which he denounced not because he disagreed with the goal but he thought the method, though non-violent, was confrontational (Dutta and Robinson 1995, 239-240). He recruited scholars, donors, and officials from many countries to help the Institute use schooling to "free villages from the shackles of helplessness and ignorance" by "vitalizing knowledge" (308-9).

His philosophy of education drew on Western and Eastern pedagogy. He wanted to utilize the best of both traditions. He understood his school as standing in the ancient tradition of the universities and Buddhist schools of wisdom that existed 2,000 years earlier. Students also worked on the farm. He encouraged a sense of co-responsibility and of serving the needs of others. Everyone needed, he said, to excel at something so that they can realize their own moral value. He did not want education to be the preserve of the elite. He wanted his school to be "a rendezvous for Western and Asian scholars and a conduit between Asia's past and present, so that the ancient learning might be rejuvenated through contact with modern thinking." Hence the university's motto is "Where the whole world meets in one nest." Children, he said, learn best through action, including play—a very enlightened pedagogy at the time. The idea of a caring, sharing community was very important to him.

In the early 1930s, he also grew more concerned about India's "abnormal caste consciousness" and Dalit (out caste) Untouchability, lecturing on its evils, writing poems and dramas with Untouchable protagonists, and appealing to authorities at Kerala's Guruvayoor Temple (303 and 309).

Twilight years (1932–1941)

In his last decade, Tagore remained in the public limelight. On July 14, 1930, he had a widely publicized meeting with Albert Einstein. He publicly upbraided Gandhi for stating that a massive January 15, 1934 earthquake in Bihar constituted divine retribution for the subjugation of Dalits (312-313). He also mourned the incipient socio-economic decline of Bengal and the endemic poverty of Calcutta; he detailed the latter in an unrhymed hundred-line poem whose technique of searing double vision would foreshadow Satyajit Ray's film Apur Sansar (“The World of Apu”) (335-338). Tagore also compiled fifteen volumes of writings, including the prose-poems works Punashcha (1932), Shes Saptak (1935), and Patraput (1936). He continued his experimentations by developing prose-songs and dance-dramas, including Chitrangada (1936) [2], Shyama (1939), and Chandalika (1938). He wrote the novels Dui Bon (1933), Malancha (1934), and Char Adhyay (1934). Tagore took an interest in science in his last years, writing Visva-Parichay (a collection of essays) in 1937. He explored biology, physics, and astronomy. Meanwhile, his poetry—containing extensive naturalism—underscored his respect for scientific laws. He also wove the process of science (including narratives of scientists) into many stories contained in such volumes as Se (1937), Tin Sangi (1940), and Galpasalpa (1941) (see Asiatic Society of Bangladesh 2006).

Oxford University awarded him an honorary doctorate in 1940. Tagore's last four years (1937–1941) were marked by chronic pain and two long periods of illness. These began when Tagore lost consciousness in late 1937; he remained comatose and near death for an extended period. This was followed in late 1940 by a similar spell, from which he never recovered. The poetry Tagore wrote in these years is among his finest, and is distinctive for its preoccupation with death. These more profound and mystical experimentations allowed Tagore to be known as a "modern poet" (338). After this extended suffering, Tagore died on August 7, 1941, in an upstairs room of the Jorasanko mansion in which he was raised (363 and 367). His death anniversary is still mourned in public functions held across the Bengali-speaking world.

Travels

Owing to his notable wanderlust, between 1878 and 1932 Tagore visited more than thirty countries on five continents (374-376). Many of these trips were crucial in familiarizing non-Bengali audiences with his works and spreading his political ideas. For example, in 1912, he took a sheaf of his translated works to England, where they impressed missionary and Gandhi protégé Charles F. Andrews, Anglo-Irish poet William Butler Yeats (who would win the Nobel Prize in 1923), Ezra Pound, Robert Bridges, Ernest Rhys, Thomas Sturge Moore, and others (178-179). Yeats wrote the preface to the English translation of Gitanjali, while Andrews joined Tagore at Santiniketan. "These lyrics," wrote Yeats, “display in their thought a world I have dreamed all my life. Work of a supreme culture...." (Introduction, iv). Yeats’ own fascination for India is reflected in his own writing, which included a translation of the Upanishads (1975).

Tagore had been reluctant to publish in India, but these friends convinced his that he should. In November 1912 he toured the United States and the United Kingdom, staying in Butterton, Staffordshire, with Andrews’ clergymen friends (Chakravarty 1961, 1-2). From May 3, 1916 until April 1917, Tagore went on lecturing circuits in Japan and the United States during which he denounced nationalism—particularly that of the Japanese and Americans. He also wrote the essay "Nationalism in India," attracting both derision and praise (the latter from pacifists, including Romain Rolland (1888-1944), winner of the 1915 Noble Prize in Literature) (Chakravarty 1961, 182).

Shortly after returning to India, the 63-year-old Tagore visited Peru at the invitation of the Peruvian government, and took the opportunity to also visit Mexico. Both governments pledged donations of $100,000 to the school at Shantiniketan (Visva-Bharati) in commemoration of his visits (Dutta and Robinson 1995, 253). A week after his November 6, 1924 arrival in Buenos Aires, Argentina, an ill Tagore moved into the Villa Miralrío at the behest of Victoria Ocampo (1890-1979), the famous Argentinean intellectual and writer. He left for Bengal in January 1925. On May 30, 1926, Tagore reached Naples, Italy; he met fascist dictator Benito Mussolini in Rome the next day (267). Their initially warm rapport lasted until Tagore spoke out against Mussolini on July 20, 1926 (270-271).

On July 14, 1927, Tagore and two companions embarked on a four-month tour of Southeast Asia, visiting Bali, Java, Kuala Lumpur, Malacca, Penang, Siam, and Singapore. The travelogues from this tour were collected into the work Jatri (Chakravarty 1961, 1). In early 1930 he left Bengal for a nearly year-long tour of Europe and the U.S. On his return to the U.K., while his paintings were being exhibited in Paris and London, he stayed at a Religious Society of Friends settlement, Woodbrooke Colle, in Selly Oak, Birmingham. There, he wrote his Hibbert Lectures for the University of Oxford (which dealt with the "idea of the humanity of our God, or the divinity of Man the Eternal") and spoke at London's annual Quaker gathering (Dutta and Robinson 1995, 289-92 and Tagore 1931). There, addressing relations between the British and Indians (a topic he would grapple with over the next two years), Tagore spoke of a "dark chasm of aloofness." Tagore would also write about how it had been English literature that had first introduced him to the noble ideals of fair play, justice, concern for the under-dog, as well as to notions of democracy and freedom. Later, he saw how the English seemed in India to preserve these for themselves, and “disowned [them] whenever questions of national self-interest were involved” (cited by Nehru 1946: 322; Dutta and Robinson 1995, 303-304).

He later visited Aga Khan III (leader of the Ismaili Muslims), stayed at Dartington Hall, then toured Denmark, Switzerland, and Germany from June to mid-September 1930, then the Soviet Union (292-293). In April 1932 Tagore—who was acquainted with the legends and works of the Persian mystic Hafez—was invited as a personal guest of Reza Shah Pahlavi of Iran (Chakravarty 1961, 2; Dutta and Robinson 315).

Such extensive travels allowed Tagore to interact with many notable contemporaries, including Henri Bergson, Albert Einstein, Robert Frost, Mahatma Gandhi, Thomas Mann, George Bernard Shaw, H.G. Wells, Subhas Bose and Romain Rolland. Tagore's last travels abroad, including visits to Persia and Iraq in 1932 and Ceylon in 1933 only sharpened his opinions regarding human divisions and nationalism. His commitment to creating a multi-cultural world was renewed as a result of this experience (Dutta and Robinson, 317). His fame has transformed him into an unofficial cultural ambassador.

Works

Tagore's literary reputation is disproportionately influenced by regard for his poetry; however, he also wrote novels, essays, short stories, travelogues, dramas, and thousands of songs. Of Tagore's prose, his short stories are perhaps most highly regarded; indeed, he is credited with originating the Bangla-language version of the genre. His works are frequently noted for their rhythmic, optimistic, and lyrical nature. However, such stories mostly borrow from deceptively simple subject matter—the lives of ordinary people.

Novels and non-fiction

Tagore wrote eight novels and four novellas, including Chaturanga, Shesher Kobita, Char Odhay, and Noukadubi. Ghare Baire (“The Home and the World”)— through the lens of the idealistic zamindar protagonist Nikhil—excoriates rising Indian nationalism, terrorism, and religious zeal in the Swadeshi movement. A frank expression of Tagore's conflicted sentiments, it emerged out of a 1914 bout of depression. Indeed, the novel bleakly ends with Hindu-Muslim sectarian violence and Nikhil's being (probably mortally) wounded (192-194). In some sense, Gora shares the same theme, raising controversial questions regarding the Indian identity. As with Ghare Baire, matters of self-identity (jāti), personal freedom, and religion are developed in the context of a family story and love triangle (154-155).

Another powerful story is Yogayog (Nexus), where the heroine Kumudini—bound by the ideals of Shiva-Sati, exemplified by Dākshāyani, is torn between her pity for the sinking fortunes of her progressive and compassionate elder brother and her exploitative, rakish, and patriarchical husband. In it, Tagore demonstrates his feminist leanings, using pathos to depict the plight and ultimate demise of Bengali women trapped by pregnancy, duty, and family honor; simultaneously, he treats the decline of Bengal's landed oligarchy (Mukherjee 2004).

Other novels were more uplifting: Shesher Kobita (translated as “Last Poem” or “Farewell Song”) is his most lyrical novel, with poems and rhythmic passages written by the main character (a poet). It also contains elements of satire and post-modernism, whereby stock characters gleefully attack the reputation of an old, outmoded, oppressively renowned poet who, incidentally, goes by the name of Rabindranath Tagore.

Though his novels remain among the least-appreciated of his works, they have been given renewed attention via film adaptations by such directors as Satyajit Ray; these include Chokher Bali and Ghare Baire; many have soundtracks featuring selections from Tagore's own rabindrasangit. Tagore also wrote many non-fiction books on topics ranging from Indian history to linguistics. In addition to autobiographical works, his travelogues, essays, and lectures were compiled into several volumes, including Iurop Jatrir Patro (“Letters from Europe”) and Manusher Dhormo (“The Religion of Man”).

Music and artwork

Tagore was an accomplished musician and painter, writing around 2,230 songs. They comprise rabindrasangit (“Tagore Song"), now an integral part of Bengali culture in both India and Bangladesh. Tagore's music is inseparable from his literature, most of which became lyrics for his songs. Primarily influenced by the thumri style of Hindustani classical music, they ran the entire gamut of human emotion, ranging from his early dirge-like Brahmo devotional hymns to quasi-erotic compositions (Dutta and Robinson, 94). They emulated the tonal color of classical ragas to varying extents, while at times his songs mimicked a given raga's melody and rhythm faithfully, he also blended elements of different ragas to create innovative works (Dasgupta 2001). For Bengalis, their appeal—stemming from the combination of emotive strength and beauty described as surpassing even Tagore's poetry—was such that the Modern Review observed that "[t]here is in Bengal no cultured home where Rabindranath's songs are not sung or at least attempted to be sung ... Even illiterate villagers sing his songs." Music critic Arther Strangeways of The Observer first introduced non-Bengalis to rabindrasangit with his book The Music of Hindustani, which described it as a "vehicle of a personality ... [that] go behind this or that system of music to that beauty of sound which all systems put out their hands to seize (Dutta and Robinson, 359).

When Yeats visited India, he was impressed to hear women tea-pickers singing Tagore's songs in a very poor part of the country. Two of Tagore's songs are national anthems—Bangladesh's Amar Sonaar Bengali and India's Jana Gana Mana. Tagore thus became the only person ever to have written the national anthems of two nations. In turn, rabindrasangit influenced the styles of such musicians as sitar maestro Vilayat Khan, the sarodiya Buddhadev Dasgupta, and composer Amjad Ali Khan (Dasgupta 2001).

At age 60, Tagore took up drawing and painting; successful exhibitions of his many works—which made a debut appearance in Paris upon encouragement by artists he met—were held throughout Europe. Tagore—who likely exhibited protanopia ("color blindness"), or partial lack of (red-green, in Tagore's case) color discernment—painted in a style characterized by peculiarities in aesthetics and coloring schemes. Nevertheless, Tagore took to emulating numerous styles, including that of craftwork by the Malanggan people of northern New Ireland, Haida carvings from the Pacific Northwest region of North America, and woodcuts by Max Pechstein (Dyson 2001). Tagore also had an artist's eye for his own handwriting, embellishing the scribbles, cross-outs, and word layouts in his manuscripts with simple artistic leitmotifs, including simple rhythmic designs. His nephews, Gaganendranath and Abanindranath, were acclaimed painters.

Theatrical pieces

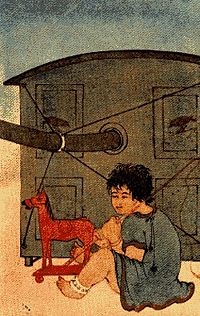

Tagore's experience in theater began at age 16, when he played the lead role in his brother Jyotirindranath's adaptation of Molière's Le Bourgeois Gentilhomme. At age twenty, he wrote his first drama-opera—Valmiki Pratibha (“The Genius of Valmiki”)—which describes how the bandit Valmiki reforms his ethos, is blessed by Saraswati (goddess of learning), and composes the Rāmāyana (Chakravarti, 123). Through it, Tagore vigorously explores a wide range of dramatic styles and emotions, including usage of revamped kirtans (Hindu devotional songs) and adaptation of traditional English and Irish folk melodies as drinking songs (Dutta and Robinson, 79-81). Another notable play, Dak Ghar (“The Post Office”), describes how a child—striving to escape his stuffy confines—ultimately "fall[s] asleep" (which suggests his physical death). A story with worldwide appeal (it received rave reviews in Europe), Dak Ghar dealt with death as, in Tagore's words, "spiritual freedom [from] the world of hoarded wealth and certified creeds" (21-23; Chakravarty, 123-124).

His other works—emphasizing fusion of lyrical flow and emotional rhythm tightly focused on a core idea—were unlike previous Bengali dramas. His works sought to articulate, in Tagore's words, "the play of feeling and not of action." In 1890 he wrote Visarjan (“Sacrifice”), regarded as his finest drama (Chakravarty, 123). The Bangla-language originals included intricate subplots and extended monologues. Later, his dramas probed more philosophical and allegorical themes; these included Dak Ghar. Another is Tagore's Chandalika (“Untouchable Girl”), which was modeled on an ancient Buddhist legend describing how Ananda—the Gautama Buddha's disciple—asks water of an Adivasi ("untouchable") girl (Chakravarty, 124). Lastly, among his most famous dramas is Raktakaravi (“Red Oleanders”), which tells of a kleptocratic king who enriches himself by forcing his subjects to mine. The heroine, Nandini, eventually rallies the common people to destroy these symbols of subjugation. Tagore's other plays include Chitrangada, Raja, and Mayar Khela.

Short stories

The four years from 1891 to 1895 are known as Tagore’s Sadhana period (named for one of Tagore’s magazines). This period was among Tagore's most fecund, yielding more than half the stories contained in the three-volume Galpaguchchha, which itself is a collection of eighty-four stories (Chakravarty, 45). Such stories usually showcase Tagore’s reflections upon his surroundings, on modern and fashionable ideas, and on interesting mind puzzles (which Tagore was fond of testing his intellect with).

Tagore typically associated his earliest stories (such as those of the Sadhana period) with an exuberance of vitality and spontaneity; these characteristics were intimately connected with Tagore’s life in the common villages of, among others, Patisar, Shajadpur, and Shilaida, while managing the Tagore family’s vast landholdings. There, he beheld the lives of India’s poor and common people. Tagore thereby took to examining their lives with a penetrative depth and feeling that was singular in Indian literature up to that point (Chakravarty 1961, 45-46). In "The Fruitseller from Kabul," Tagore speaks in first person as town-dweller and novelist who chances upon the Afghani seller. He attempts to distill the sense of longing felt by those long trapped in the mundane and hardscrabble confines of Indian urban life, giving play to dreams of a different existence in the distant and wild mountains:

There were autumn mornings, the time of year when kings of old went forth to conquest; and I, never stirring from my little corner in Calcutta, would let my mind wander over the whole world. At the very name of another country, my heart would go out to it ... I would fall to weaving a network of dreams: the mountains, the glens, the forest... (Chakravarty 48-49)

Many of the other Galpaguchchha stories were written in Tagore’s Sabuj Patra period (1914–1917; also named for one of Tagore's magazines) (45).

Tagore's Golpoguchchho (“Bunch of Stories”) remains among Bangla literature's most popular fictional works, providing subject matter for many successful films and theatrical plays. Satyajit Ray's film Charulata was based upon Tagore's controversial novella, Nastanirh (“The Broken Nest”). In Atithi (also made into a film), the young Brahmin boy Tarapada shares a boat ride with a village zamindar (landlord). The boy reveals that he has run away from home, only to wander around ever since. Taking pity, the zamindar adopts him and ultimately arranges his marriage to the zamindar's own daughter. However, the night before the wedding, Tarapada runs off—again.

Strir Patra (“The Letter from the Wife”) is among Bangla literature's earliest depictions of the bold emancipation of women. The heroine Mrinal, the wife of a typical patriarchical Bengali middle class man, writes a letter while she is traveling (which constitutes the whole story). It details the pettiness of her life and struggles; she finally declares that she will not return to her husband's home with the statement Amio bachbo. Ei bachlum ("And I shall live. Here, I live").

In Haimanti, Tagore takes on the institution of Hindu marriage, describing the dismal lifelessness of married Bengali women, hypocrisies plaguing the Indian middle classes, and how Haimanti, a sensitive young woman, must—due to her sensitiveness and free spirit—sacrifice her life. In the last passage, Tagore directly attacks the Hindu custom of glorifying Sita's attempted self-immolation as a means of appeasing her husband Rama's doubts.

Tagore also examines Hindu-Muslim tensions in Musalmani Didi, which in many ways embodies the essence of Tagore's humanism. On the other hand, Darpaharan exhibits Tagore's self-consciousness, describing a young man harboring literary ambitions. Though he loves his wife, he wishes to stifle her own literary career, deeming it unfeminine. Tagore himself, in his youth, seems to have harbored similar ideas about women. Darpaharan depicts the final humbling of the man via his acceptance of his wife's talents. As many other Tagore stories, Jibito o Mrito (life or death) provides the Bengalis with one of their more widely used epigrams: Kadombini moriya proman korilo she more nai ("Kadombini died, thereby proved that she hadn't").

Poetry

Tagore's poetry—which varied in style from classical formalism to the comic, visionary, and ecstatic—proceeds out a lineage established by fifteenth- and sixteenth-century Vaishnavite poets. Tagore was also influenced by the mysticism of the rishi-authors who—including Vyasa—wrote the Upanishads, the Bhakta-Sufi mystic Kabir, and Ramprasad (Roy 1977, 201). Yet Tagore's poetry became most innovative and mature after his exposure to rural Bengal's folk music, which included ballads sung by Bāul folk singers—especially the bard Lālan Śāh (Stewart and Twichell, 94; Urban 2001, 18). These—which were rediscovered and popularised by Tagore—resemble nineteenth-century Kartābhajā hymns that emphasize inward divinity and rebellion against religious and social orthodoxy (6-7, 16).

During his Shelidah years, his poems took on a lyrical quality, speaking via the manner manus (the Bāuls' "man within the heart") or meditating upon the jivan devata ("living God within"). This figure thus sought connection with divinity through appeal to nature and the emotional interplay of human drama. Tagore used such techniques in his Bhānusiṃha poems (which chronicle the romanticism between Radha and Krishna), which he repeatedly revised over the course of seventy years (Stewart and Twichell, 7).

Later, Tagore responded to the (mostly) crude emergence of modernism and realism in Bengali literature by writing experimental works in the 1930s (Dutta and Robinson, 281). Examples works include Africa and Camalia, which are among the better known of his latter poems. He also occasionally wrote poems using Shadhu Bhasha (the high form of Bangla); later, he began using Cholti Bhasha (the low form). Other notable works include Manasi, Sonar Tori (“Golden Boat”), Balaka (“Wild Geese,” the title being a metaphor for migrating souls) and Purobi.

Sonar Tori's most famous poem—dealing with the ephemeral nature of life and achievement—goes by the same name; it ends with the haunting phrase "Shunno nodir tire rohinu poŗi / Jaha chhilo loe gêlo shonar tori"—"all I had achieved was carried off on the golden boat—only I was left behind"). Internationally, Gitanjali is Tagore's best-known collection, winning him his Nobel Prize (Stewart and Twichell, 95-96).

Political views

Marked complexities characterize Tagore's political views. Though he criticized European imperialism and supported Indian nationalism, he also lampooned the Swadeshi movement, denouncing it in "The Cult of the Spinning Wheel,” an acrid 1925 essay (Dutta and Robinson, 261). Instead, he emphasized self-help and intellectual uplift of the masses, stating that British imperialism was not as a primary evil, but instead a "political symptom of our social disease," urging Indians to accept that "there can be no question of blind revolution, but of steady and purposeful education" (Chakravarty, 181).

Such views inevitably enraged many, placing his life in danger: during his stay in a San Francisco hotel in late 1916, Tagore narrowly escaped assassination by Indian expatriates—the plot failed only because the would-be assassins fell into argument (Dutta and Robisnon, 204). Yet Tagore wrote songs lionizing the Indian independence movement. Despite his tumultuous relations with Gandhi, Tagore was also key in resolving a dispute between Gandhi and B. R. Ambedkar involving separate electorates for untouchables, ending a fast "unto death" by Gandhi (339).

Tagore also criticized orthodox (rote-oriented) education, lampooning it in the short story "The Parrot's Training," where a bird—which ultimately dies—is caged by tutors and force-fed pages torn from books (267). These views led Tagore—while visiting Santa Barbara, California, on October 11, 1917—to conceive of a new type of university, desiring to "make [his ashram at] Santiniketan the connecting thread between India and the world ... [and] a world center for the study of humanity ... somewhere beyond the limits of nation and geography (204}}. The school—which he named Visva-Bharati had its foundation stone laid on December 22, 1918; it was later inaugurated on December 22, 1921 (220).

Here, Tagore implemented a brahmacharya (traditional celibate or student stage in life) pedagogical structure employing gurus to provide individualized guidance for pupils. Tagore worked hard to fund raise for and staff the school, even contributing all of his Nobel Prize monies (Roy, 175). Tagore’s duties as steward and mentor at Santiniketan kept him busy; he taught classes in mornings and wrote the students' textbooks in afternoons and evenings (Chakravarty, 27). Tagore also fundraised extensively for the school in Europe and the United States.

Religious Philosophy

Religious ideas permeated Tagore’s thought and work. His father had been a leader of the reformist Brahmo Samaj, which stressed belief in an un-manifest God, rejected worship, identified with Unitarianism and organized itself as a Protestant-type church (a word used by the movement). External symbols and trappings of religion were minimized. Tagore wrote and spoke about the divinity of nature; a “super-soul” permeated all things (1931: 22). He wrote of the “humanity of God” and of the “divinity of man” (25). All “true knowledge and service” emanate from the source of all that is. “Service,” he famously said, “is joy.”

Tagore believed in the greatness of humanity, but warned that nature had to be nurtured and not exploited. He aspired to create a new world civilization that would draw on the nobility of all culture. Communication between East and West would lay the groundwork for peace. His school curriculum drew on Buddhism, Jainism, Chinese religion, Christianity, Islam, and Hinduism. He combined Western and Eastern philosophy. He believed in an underlying unity and set out to Aesthetic development went hand-in-hand with academic pursuit. He was “proud of his [humanity when he] could acknowledge the poets and artists of other countries as his own” (cited by Sen 1997). He always wanted to build bridges, to set our minds free by breaking down our “narrow, domestic walls.” He believed that India should not turn its back on Western technology, but adapt it to India’s own ethos. Haroild Hjärne, presenting Tagore’s Nobel Prize, said:

He peruses his Vedic hymns, his Upanishads, and indeed the theses of Buddha himself, in such a manner that he discovers in them, what is for him an irrefutable truth. If he seeks the divinity in nature, he finds there a living personality with the features of omnipotence, the all-embracing lord of nature, whose preternatural spiritual power nevertheless likewise reveals its presence in all temporal life, small as well as great, but especially in the soul of man predestined for eternity. Praise, prayer, and fervent devotion pervade the song offerings that he lays at the feet of this nameless divinity of his. Ascetic and even ethic austerity would appear to be alien to his type of divinity worship, which may be characterized as a species of aesthetic theism. Piety of that description is in full concord with the whole of his poetry, and it has bestowed peace upon him. He proclaims the coming of that peace for weary and careworn souls even within the bounds of Christendom. (1913

)

Where the Mind is Without Fear

His poem “Where the Mind is Without Fear” perhaps best sums up his ideas:

(Gitanjali, poem 35 [3]). |

||

Impact and legacy

Tagore's posthumous impact can be felt through the many festivals held worldwide in his honor—examples include the annual Bengali festival/celebration of Kabipranam (Tagore's birthday anniversary), the annual Tagore Festival held in Urbana, Illinois in the United States, the Rabindra Path Parikrama walking pilgrimages leading from Calcutta to Shantiniketan, and ceremonial recitals of Tagore's poetry held on important anniversaries. This legacy is most palpable in Bengali culture, ranging from language and arts to history and politics; indeed, Nobel laureate Amartya Sen noted that even for modern Bengalis, Tagore was a "towering figure," being a "deeply relevant and many-sided contemporary thinker.” Tagore's collected Bangla-language writings—the 1939 Rabī Racanāvalī—is also canonized as one of Bengal's greatest cultural treasures, while Tagore himself has been proclaimed "the greatest poet India has produced” (Kämpchen 2003). Tagore's poetry has been set to music by various composers, among them Arthur Shepherd's Triptych for Soprano and String Quartet.

Tagore has also attained fame throughout much of Europe, North America, and East Asia. He was key in founding Dartington Hall School, a progressive coeducational institution. In Japan, he influenced such figures as Nobel laureate Yasunari Kawabata (Dutta and Robinson, 202). Tagore's works were widely translated into many European languages—a process that began with Czech indologist Vincent Slesny (Cameron 2006) and French Nobel laureate André Gide—including Russian, English, Dutch, German, Spanish, and others. In the United States, Tagore's popular lecturing circuits (especially those between 1916–1917) were widely attended and highly acclaimed.

Tagore, through Spanish translations of his works, also influenced leading figures of Spanish literature, including Chileans Pablo Neruda and Gabriela Mistral, Mexican writer Octavio Paz, and Spaniards José Ortega y Gasset, Zenobia Camprubí, and Juan Ramón Jiménez. Between 1914 and 1922, the Jiménez-Camprubí spouses translated no less than twenty-two of Tagore's books from English into Spanish. Jiménez, as part of this work, also extensively revised and adapted such works as Tagore's The Crescent Moon. Indeed, during this time, Jiménez developed the now-heralded innovation of "naked poetry" (Dutta and Robinson, 254-255). Meanwhile, Ortega y Gasset wrote:

Tagore's wide appeal [may stem from the fact that] he speaks of longings for perfection that we all have ... Tagore awakens a dormant sense of childish wonder, and he saturates the air with all kinds of enchanting promises for the reader, who ... pays little attention to the deeper import of Oriental mysticism.

Tagore's works—alongside works by Dante, Cervantes, Goethe, Plato, and Leo Tolstoy—were published in free editions around 1920. Modern remnants of a once widespread Latin American reverence of Tagore were discovered, for example, by an astonished Salman Rushdie during his 1986 trip to Nicaragua (Dutta and Robinson, 255). But, over time, Tagore's talents came to be regarded by many as over-rated, leading Graham Greene to say in 1937, "I cannot believe that anyone but Mr. Yeats can still take his poems very seriously" (Sen 1997).

Tagore was mired in several notable controversies, including his dealings with Indian nationalists Subhas Chandra Bose and his expressions of admiration for Soviet-style Communism. Papers confiscated from Indian nationalists in New York allegedly implicating Tagore in a plot to use German funds to overthrow the British Raj (Dutta and Robinson, 212). The latter allegation caused Tagore's book sales and popularity among the U.S. public to plummet (214). Lastly, his relations with and ambivalent opinion of Italian dictator Benito Mussolini revolted many, causing Romain Rolland (a close friend of Tagore's) to state that "[h]e is abdicating his role as moral guide of the independent spirits of Europe and India" (qtd. in Dutta and Robinson, 273).

The main value of his legacy, however, is his universal worldview, his desire to always build bridges not barriers, he willingness to be eclectic in his thought and to derive value from all cultures.

Bibliography (partial)

|

|

References

ISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Asiatic Society of Bangladesh. 2006. "Tagore, Rabindranath", Banglapedia April 5, 2006.

- Cameron, R. "Exhibition of Bengali film posters opens in Prague". Radio Prague (April 5, 2006).

- Chakrabarti, I. 2001. "A People's Poet or a Literary Deity." Parabaas ([www.parabaas.com Online Bengali Resource)

- Chakravarty, A. 1961. A Tagore Reader. Boston, MA: Beacon Press. ISBN 0807059714.

- Dasgupta, A. 2001. Rabindra-Sangeet as a Resource for Indian Classical Bandishes. Parabaas.

- Dutta, Krishna and Andrew Robinson. 1995. A Rabindranath Tagore: The Myriad-Minded Man. New York: St. Martin's Press. ISBN 0312140304.

- Dutta, Krishna and Andrew Robinson (eds.). 1997. Rabindranath Tagore: An Anthology. New York: St. Martin's Press. ISBN 0312169736.

- Dyson, K. K. 2001. “Rabindranath Tagore and his World of Colors.” Parabaas.

- Frenz, H (ed.). 1969. Rabindranath Tagore—Biography. Nobel Foundation.

- Hatcher, B. A. 2001. Aji Hote Satabarsha Pare: What Tagore Says To Us A Century Later. Parabaas.

- Hjärne, H. 1913. The Nobel Prize in Literature 1913", Nobel Foundation. [4]

- Indo-Asian News Service. 2005. "Recitation of Tagore's Poetry of Death." Hindustan Times.

- Kämpchen, M. 2003. “Rabindranath Tagore In Germany.” Parabaas.

- Meyer, L. 2004. “Tagore in The Netherlands.” Parabaas.

- Mukherjee, M. 2004. "Yogayog (Nexus) by Rabindranath Tagore: A Book Review." Parabaas.

- Nehru, Jawahaelal. 1946. The Discovery of India. Calcutta: The Signett Press; New York: Oxford University Press, centenary ed., 1990. ISBN 0195623592

- Radice, W. 2003. "Tagore's Poetic Greatness.” Parabaas.

- Robinson, A. "Tagore, Rabindranath". Encyclopædia Britannica.

- Roy, B. K. 1997. Rabindranath Tagore: The Man and His Poetry. Folcroft, PA: Folcroft Library Editions. ISBN 0841473307.

- Sen, A. 1997. "Tagore and His India." New York Review of Books 11: 44. (http://www.countercurrents.org/culture-sen281003.htm and http://nobelprize.org/literature/articles/sen/)

- Sil, N. P. 2005. "Devotio Humana: Rabindranath's Love Poems Revisited." Parabaas.

- Tagore, R. and P.B. Pal (transl.). 1918. "The Parrot's Tale." Parabaas.

- Tagore, R. 1997. Collected Poems and Plays of Rabindranath Tagore. London: Macmillan Publishing. ISBN 0026159201.

- Tagore, R. 1931. The Religion of Man. London: Macmillan. New edition, 2004. Rhinebeck, NY: Monkfish Book Publishing. ISBN 0972635785

- Stewart, T. & Chase Twichell (eds. and trans.). 2003. Rabindranath Tagore: Lover of God. Port Townsemd, WA: Copper Canyon Press. ISBN 1556591969.

- Tagore Festival Committee. 2006. "History of the Tagore Festival." College of Business, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign.

- Urban, H. B. 2001. Songs of Ecstasy: Tantric and Devotional Songs from Colonial Bengal. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0195139011.

- Yeats, W. B. and Swami Shree Purohit. 1937. The Ten Principal Upanishads. London: Macmillan. 1975 edition. ISBN 0020715501

Further reading

- Chaudhuri, A. 2004. The Vintage Book of Modern Indian Literature. New York: Vintage Books. ISBN 037571300X

- Deutsch, A. and A. Robinson. 1989. The Art of Rabindranath Tagore. New York: Monthly Review Press. ISBN 0233983597

- Deutsch, A. and A. Robinson (eds.). 1997. Selected Letters of Rabindranath Tagore. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521590183

- Tagore, R. 2000. Gitanjali. New Delhi: Macmillan India Ltd. ISBN 0333935756

External links

All links retrieved December 7, 2022.

1901: Sully Prudhomme | 1902: Theodor Mommsen | 1903: Bjørnstjerne Bjørnson | 1904: Frédéric Mistral, José Echegaray | 1905: Henryk Sienkiewicz | 1906: Giosuè Carducci | 1907: Rudyard Kipling | 1908: Rudolf Christoph Eucken | 1909: Selma Lagerlöf | 1910: Paul Johann Ludwig von Heyse | 1911: Maurice Maeterlinck | 1912: Gerhart Hauptmann | 1913: Rabindranath Tagore | 1915: Romain Rolland | 1916: Verner von Heidenstam | 1917: Karl Adolph Gjellerup, Henrik Pontoppidan | 1919: Carl Spitteler | 1920: Knut Hamsun | 1921: Anatole France | 1922: Jacinto Benavente | 1923: William Butler Yeats | 1924: Władysław Reymont | 1925: George Bernard Shaw |

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.

↧ Download as ZWI file | Last modified: 02/03/2023 23:52:08 | 169 views

☰ Source: https://www.newworldencyclopedia.org/entry/Rabindranath_Tagore | License: CC BY-SA 3.0

ZWI signed:

ZWI signed:

KSF

KSF