Billy Sunday

From Conservapedia

From Conservapedia Billy Sunday (his real name; in full, William Ashley Sunday) (1862-1935) was, during his heyday—roughly 1910-20—the most famous evangelist in America. In his revival meetings hundreds of thousands of people accepted his invitation to come forward and "hit the sawdust trail" (publicly declare their commitment to Christ). Over a hundred million people heard Sunday in person, and by his account he converted a million of them.[1] His large-scale events, which blended preaching with elements of salesmanship, showmanship, and business-like organization, were unlike anything that had preceded him.[2]

Contents

Baseball player to preacher[edit]

His first career was as baseball player with the Chicago White Stockings from 1883-7, the Pittsburgh Alleghenies in 1888-90, and briefly with the Philadelphia Phillies.[3] He was a well-known and notable player (though not stellar), famous for his running speed in the outfield and as a base stealer. He was clocked rounding the bases in fourteen seconds, and in footraces he beat out both the fastest runner in a competing baseball league and a professional sprinter.[4] For many years Billy Sunday held the record for the most stolen bases in a season (95), until Ty Cobb broke it in 1915.

A hard drinker off the field, in 1886 he was literally picked out of the gutter, drunk, by workers at the Chicago's Pacific Garden Mission, was converted, and stopped drinking.

In the spring of 1891 Sunday resigned his Philadelphia Phillies contract of $3000 for 6–7 months of work for an $83/month job as "Secretary of the Religious Department" at the Chicago YMCA. Two years later he became an advance man for revivalist J. Wilbur Chapman, and learned how to organize revival meetings. In January 1896 he went out on his own and hosted his first revival meeting in Garner, Iowa, and he was ordained as a Presbyterian minister in 1903.[5]

By 1914, he was a national celebrity, conducting campaigns in big cities which lasted many weeks and attracted tens of thousands of people. In 1917, he conducted a ten-week campaign in New York in which 98,000 people accepted Christ.[6] Gale's American Decades says that by 1920 he was the best-known evangelist in America.

Preaching style[edit]

Sunday was unabashedly uneducated and spoke in the plain speech of ordinary people, a marked contrast to the dignified style of other ministers. This was unusual, even shocking at the time. Schools trained students in elocution and rhetoric. Ministers and public speakers were expected to use formal, educated English. A 1920 book for English teachers bracketed Sunday with a humorist famous for introducing slang into written English:

- ...all of us enjoy baseball slang, and George Ade and his rival in slang, Billy Sunday, are popular because they use these picturesque shortcuts that in many instances are destined to become the main paths of verbal expression.[7]

A 1907 profile tells of him retelling New Testament stories in his own style:

- "Oh, but the Devil is a smooth guy! ... So the devil went out in the wilderness after the Saviour. Now, Christ was a man. He had all the attributes of a man. He was tired, he was hungry, he was lonely, just the way you and I would have been. And the Devil walks up to him and says—" [Here the preacher drew himself into ... a personification of the sneering arrogance of Mephistopheles...] "He says, 'Son of God, hey?'"

The commentator notes that at the first meetings, local ministers had "looked at each other and were horrified," but were won over, and quotes one as saying

- "The man has trampled all over me and my theology. He has kicked my teachings up and down that platform like a football. He has outraged every ideal I have had regarding my sacred profession. But what does that count, as against the results he has accomplished? My congregation will be increased by hundreds. I didn't do it. Sunday did it. It is for me to humble myself and thank God for his help. He is doing God's work. That I know."[8]

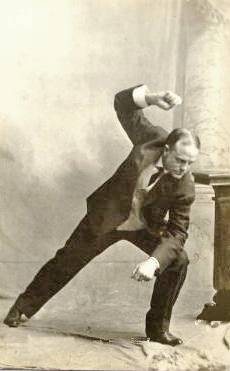

Billy Sunday gave his speech vigorous physical accompaniment. Sunday's "tabernacles" held audiences of about fifteen thousand people, to whom he spoke without any sound equipment. To one observer, his platform manners recalled those of the Broadway performer George M. Cohan, and with good reason:

- Needing to arrest the attention of an incredibly large number of people, he adopts various evolutions that have a genuine emphatic value. It is a physical language... Sunday gives to his words a drive that makes you tense in your seat. Whipping like a flash from one side of the table to the other, he makes your mind keep unison with his body."[9]

A 1917 biographer referred to his "acrobatic preaching," saying "Sunday is a physical sermon. In a unique sense he glorifies God with his body."[10] A description of him in action says

- He begins to dance like a shadow-boxer. He slaps his hands together with a report like a broken electric lamp. He poses on one foot like a fast ball pitcher winding up. He jumps upon a chair. In the stress of his routine he may stand with one foot in the chair and another on the lectern. All the while he is flaying the "whisky kings," the German war lords, slackers, suffragettes, or the local ministry. And, if his story of the sinner come home to salvation fits the gesture, he may emphasize the moral by throwing himself on the floor with an outstretched arm groping for the home plate like a baserunner sliding safely in with a stolen run.[11]

Sometimes he smashed chairs in his "rage against Satan." He perspired heavily from this vigorous performance;[5] reporters sitting near the stage had to endure a "fine rain of perspiration from the evangelist's flailing arms and contorted brow."[1]

The "Sawdust Trail"[edit]

Sunday is associated with the phrase "to hit the sawdust trail." After starting in tents, he conducted his meetings in roughly-built wooden "tabernacles." Sawdust covered the ground in lieu of a floor. At the climax of his meetings, he would call on people to come up the aisles and declare their commitment to Christ.

William T. Ellis wrote in 1914,[12] "Out in the Puget Sound country, where the sawdust aisles and the rough tabernacle made an especial appeal to the woodsmen, the phrase 'hitting the sawdust trail' came into use in Mr. Sunday's meetings." Ellis calls it a "luminous" substitute for "the older stereotyped phrases: 'going forward,' 'seeking the altar.'" and contrasts Sunday's approach with "the more conventional method, used by older evangelists, [of asking for] a show of hands."

The Encyclopedia of Evangelism says that Billy Sunday would "invite—more often, taunt—his auditors to 'hit the sawdust trail.'"[13]

Beliefs[edit]

Sunday famously claimed that he did not know "any more about theology than a jack rabbit knows about pingpong."[1] The New York Times classified him as a fundamentalist—"perhaps the most interesting Fundamentalist, next to Mr. Bryan."

He fiercely opposed alcohol:

- Whiskey and beer are all right in their place, but their place is in hell.... The saloon is the sum of all villainies. It is worse than war or pestilence. It is the crime of crimes. It is parent of crimes and the mother of sins. It is the appalling source of misery and crime in the land and the principal cause of crime. It is the source of three-fourths of the taxes to support that crime. And to license such an incarnate fiend of hell is the dirtiest, low-down, damnable business on top of this old earth.[14]

He opposed dancing: "You must want a lot of prostitutes or you wouldn't sow dances... Somebody says to me: 'Mr. Sunday, are you going to include the square dance?' They all look alike to me. It does not take very long to cut the corners off. Sure it is harmful, especially for girls. Young men can drink and gamble and frequent houses of ill fame, but the only way a girl can get recreation is in a narrow gauge buggy ride on a moonlight night or at a dance. If you can't see any harm in this kind of thing, why I guess the Lord will let you out as an idiot."[15] He opposed cigarettes: "I say to you, young girl, don't go with that godless, God-forsaken, sneering young man that walks the streets smoking cigarettes. He would not walk the streets with you if you smoked cigarettes."[10]

He believed in a literal Hell, and invoked it frequently in his sermons. He said "If we had more preaching on Hell from the pulpit, we would have less Hell in the congregation.".[16] In a sermon, he said "If you ever had any doubt about a literal Hell, a fiery Hell, where the wicked must remain forever, it would all vanish as I see Jesus Christ in Gethsemane, agonizing because men would not accept Him and were going to Hell."[17]

He considered the theory of evolution to be "bunk, junk, and poppycock."[18] He once dismissed it by saying, "I don't believe in the bastard theory that men came from protoplasm by the fortuitous concurrence of atoms."[19]

He was inclusive toward Negroes, welcoming them to his services. In 1918 he supported "industrial equality," stating that "If the Negro is good enough to fight in the trenches and to buy Liberty bonds, his girl is good enough to work alongside any white girl in the munitions factories."[20]

He favored women's right to vote. He favored sex education:[21] ("Prudery is no more a sign of virtue than a wig is of hair").

He favored labor unions, but within limits: "It would be the greatest calamity of history if Eugene V. Debs ever became president of the United States.... hell would hold a jubilee and heaven would hang a crepe on her door.... I have championed the cause of the union man all my life, but I'm dead against the radical in whatever form he may appear."[22]

Converts and financial success[edit]

He was financially successful, a point which his critics noted. It was his practice to keep the proceeds of the last day of his campaigns. He published his results measured both by numbers of converts and by dollars in thank offerings. Through 1916, he made over twenty appearances in cities ranging in size from small (Erie, Pennsylvania; Canton, Ohio) to large (Boston, Philadelphia, New York), and claimed a total of over 600,000 converts and $680,000 in donations[11] (equivalent to about $13 million today).[23] In 1920 Dun and Bradstreet estimated his worth at $1.4 million ($16 million today).

Criticism[edit]

A 1916 writer commented that

- When people who have read Billy Sunday say he is irreverent, or frivolous, or that he is a poseur, or that (as some people seem to think) he is a mere financial adventurer or speculator in sermons, the most common reply one hears from people who have heard him is, "I thought so, too, until I went and listened to him and watched him." Then for a few minutes one hears the more or less helpless apologist for Billy ... trying to explain (like explaining the flavour of a raspberry to one who won't taste one).[24]

Some questioned the permanence of Sunday's "conversions." Following the famous 1917 revival in New York, the Federal Council of Churches found that only 200 of the 68,000 were permanent converts.[11] In 1921, a commentator wrote:

- In spite of the thousands that have hit the sawdust trail, however, it is difficult to believe that more than a tiny proportion of his auditors are religiously affected by him. Very few give any signs of seriousness or "conversion." The great majority of those who hit the trail are merely people who want to shake his hand.... His audiences are curious to see him and hear him. He is a remarkable public entertainer, and much that he says has keen humor and verbal art and horse sense. But ... he leaves an impression of being at once violent and incommunicative, a salesman for Christianity but not a guide or friend.[25]

Sunday's reply to such criticisms was "They tell me a revival is only temporary; so is a bath, but it does you good."[26] He felt that it was the local clergy's job to retain the people he converted: "If you are too lazy to take care of the baby after it is born, don't blame the doctor."[9]

Sunday was criticized by the liberal clergy of the day. Left-leaning Leon Milton Birkhead called Sunday's theology "a mediaeval belief that Christianity somehow is a fire-escape from a future hell." In 1916 Unitarian minister Joel H. Metcalf said "I cannot see how any cultivated person can be other than terribly revolted by the extreme sensationalism, the coarse jokes, the super-slang, the bawd characterizations, the ribald Billingsgate, and the dancing dervish contortions of the revivalist, where perspiration seems to be confused with inspiration."[27]

Sunday fascinated the liberal intelligentsia of the time, who often made him a target of their mockery. Sinclair Lewis' novel Babbitt includes a character named Mike Monday, "the distinguished evangelist, the best-known Protestant pontiff in America.... As a prize-fighter he gained nothing but his crooked nose, his celebrated vocabulary, and his stage-presence. The service of the Lord had been more profitable." In his novel, a visit by Monday is opposed by "certain Episcopalian and Congregationalist ministers," whom Monday calls "a bunch of gospel-pushers with dish-water instead of blood, a gang of squealers that need more dust on the knees of their pants and more hair on their skinny old chests." Later, Lewis was to write Elmer Gantry, a novel about an evangelical preacher with resemblances to Sunday. (Sunday in turn referred to Lewis as "Satan's cohort.")[28]

C. E. S. Wood in Heavenly Discourse depicts Billy Sunday as going to Heaven, addressing St. Michael and God as "Hello, Mike. Howdy, Pardner," and offering to conduct a revival there: "I can pack heaven so tight the fleas will squeal, and all I want is the gate-receipts for the last performance." Carl Sandburg's poem, "To A Contemporary Bunkshooter," attacked Sunday using demotic speech similar to Sunday's own.[29]

External links[edit]

- Billy Sunday sermons, full text of eighteen of his sermons

- Video of Billy Sunday preaching

- Billy Sunday archives

See also[edit]

Notes and references[edit]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Huckster in the Tabernacle, Time Magazine, Oct. 10, 1955 (review of William G. McLoughlin's book Billy Sunday Was His Real Name)

- ↑ Plan for the New York City campaign: suggests the level of detail and preparation that went into a Billy Sunday evangelistic campaign

- ↑ Billy Sunday statistics, baseballreference.com

- ↑ Those races were reported in the Chicago Tribune, Aug. 21, 1885 and Nov. 9, 1885. The races are discussed in Sunday at the Ballpark: Billy Sunday's Professional Baseball Career 1883-1890, by Wendy Knickerbocker, Scarecrow Press, 2000, p. 42-43, 45-47.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Fundamentalism and Billy Sunday, Billy Sunday Was His Real Name, by William McLoughlin, University of Chicago Press, 1955, p. 8-11.

- ↑ Lyle Dorsett, Billy Sunday and the Redemption of Urban America, Grand Rapids: Wm. Eerdmans, 1991, p. 106-107.

- ↑ Hall-Quest, Albert Law (1920) The Textbook: How to Use and Judge it, Macmillan, p. 22

- ↑ Denison, Lindsay (1907), "The Rev. Billy Sunday and his War on the Devil." The American Magazine 64(5), September 1907, p. 454

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 "Billy Sunday," The New Republic, March 20, 1915, from The New Republic Book, p. 183

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Ellis, WIlliam T. (1917), Billy Sunday: The Man and His Message; online text at archive.org

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 "Billy Sunday Dies, Evangelist was 71," The New York Times, November 7, 1935, p. 1. Totals calculated from numbers in article.

- ↑ Ellis, William T, Billy Sunday: The Man and His Message with His Own Words Which Have Won Thousands for Christ," John C. Winston Co., Philadelphia, 1914

- ↑ The Encyclopedia of Evangelism, 2002, Westminster John Knox Press, Altar Call

- ↑ Famous 'Booze Sermon', billysunday.org

- ↑ Theatre, Cards, and Dance, sermon by Billy Sunday

- ↑ The Danger of Delay, sermon by Dr. Curtis Hutson (1934–1995)

- ↑ Gethsemane, sermon by Billy Sunday

- ↑ Hartt, Rolin Lynde (1923), "Deep Conflict Divides Protestantism," The New York Times December 16, 1923, p. XX5

- ↑ Quoted in Billy Sunday Was His Real Name, by William McLoughlin, University of Chicago Press, 1955, p. 132.

- ↑ Billy Sunday for Industrial Equality for Negro Citizens, Ohio History Society

- ↑ Famous Ames Residents: Billy Sunday, Ames Historical Society

- ↑ Karsner, David (1922), Talks with Debs in Terre Haute, New York Call; p. 57

- ↑ The Inflation Calculator

- ↑ Lee, Gerald Stanley (1916): We; a Confession of Faith for the American People During and After the War, Doubleday, Page, p. 537

- ↑ Hackett, Francis (1921), The Invisible Censor, B.W. Huebsch, Inc.; p. 30 (of reprint)

- ↑ Sayings of Billy Sunday

- ↑ Liberalism and the Modern Revival, sermon by Joel H. Metcalf, Winchester Star (Winchester, VA), December 8, 1916

- ↑ Elmer Gantry study guide, bookrags.com.

- ↑ Sandburg, Carl (1916), Chicago Poems, To A Contemporary Bunkshooter, online text at Bartleby.com

Categories: [Baseball Players] [Clergy] [Fundamentalism] [Revivals] [Progressive Era] [1920s]

↧ Download as ZWI file | Last modified: 02/14/2023 03:21:23 | 117 views

☰ Source: https://www.conservapedia.com/Billy_Sunday | License: CC BY-SA 3.0

ZWI signed:

ZWI signed:

KSF

KSF