Shanghai, China

From Nwe

From Nwe | Shanghai 上海 |

|

| — Municipality — | |

| Municipality of Shanghai • 上海市 | |

| A section of Shanghai's Pudong, east bank of Huangpu River. | |

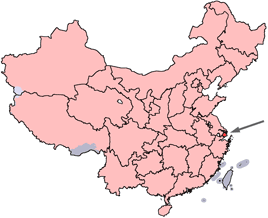

| Location within China | |

| Coordinates: 31°12′N 121°30′E | |

|---|---|

| Country | People's Republic of China |

| Settled | 5th–7th century |

| Incorporated - Town |

751 |

| - County | 1292 |

| - Municipality | 7 July 1927 |

| Divisions - County-level - Township- level |

16 districts, 1 county 210 towns and subdistricts |

| Government | |

| - Type | Municipality |

| - CPC Ctte Secretary | Yu Zhengsheng |

| - Mayor | Han Zheng |

| Area [1][2] | |

| - Municipality | 6,340.5 km² (2,448.1 sq mi) |

| - Water | 697 km² (269.1 sq mi) |

| Elevation [3] | 4 m (13 ft) |

| Population (2010)[4] | |

| - Municipality | 23,019,148 |

| - Density | 3,630.5/km² (9,402.9/sq mi) |

| Time zone | China standard time (UTC+8) |

| Postal code | 200000 – 202100 |

| Area code(s) | 21 |

| GDP[5] | 2011 |

| - Total | CNY 1.92 trillion US$ 297 billion (11th) |

| - Per capita | CNY 82,560 US$ 12,784 (2nd) |

| - Growth | |

| HDI (2008) | 0.908 (1st) – very high |

| Licence plate prefixes | 沪A, B, D, E, F,G ,H, J, K 沪C (outer suburbs) |

| City flower | Yulan magnolia |

| Website: www.shanghai.gov.cn | |

Shanghai, situated on the banks of the Yangtze River Delta, is China's largest city. The city's development in the past few decades has made it one of the most important economic, commercial, financial and communications centers of China. Until the nineteenth century, Shanghai was not a major city, and in contrast to other major Chinese cities, has only a few ancient Chinese landmarks. The Treaty of Nanjing in 1842, followed by the Treaty of the Bogue (1843) and the Sino-American Treaty of Wangsia (1844) opened Shanghai to international trade and gave foreign nations extraterritoriality on Chinese soil, opening a floodgate to western culture and influence. Shanghai quickly developed into a center for trade and investment in China, and grew into a thriving metropolis of two cities, a chaotic Chinese city, and a Western city which was one of the most modern "European" cities in the world.

After 1927, Chiang Kai-shek’s nationalist government made Shanghai their capital, building large modern Chinese residential areas, with good roads and parking lots for automobiles, north of the foreign concessions. During World War II, Japan occupied Shanghai. On May 27, 1949, Shanghai came under the control of the Communist Party of China, and along with Beijing, was one of the only two former Republic of China municipalities not immediately merged into neighboring provinces over the next decade. Until 1991, Shanghai contributed 70 percent of the total tax revenue of the Peoples Republic of China, and was denied economic liberalization because of its importance to China's fiscal well-being. In 1992, the central government under Jiang Zemin, a former Mayor of Shanghai, began reducing the tax burden on Shanghai and encouraging both foreign and domestic investment. Since then it has experienced continuous economic growth of between 9–15 percent annually.

Administratively, Shanghai is one of four municipalities of the People's Republic of China that have provincial-level status. Shanghai is also home to the world's busiest port, followed by Singapore and Rotterdam.

Name

The two characters in the name "Shanghai" literally mean "up/above" and "sea." The earliest occurrence of this name dates from the Song Dynasty, at which time there was already a river confluence and a town called "Shanghai" in the area. There are disputes as to how the name should be interpreted, but official local histories have consistently said that it means "the upper reaches of the sea/ocean."

In Chinese, Shanghai's abbreviations are Hù and Shēn. The former is derived from the ancient name of the river now known as the Suzhou River. The latter is derived from the name of Chun Shen Jun, a nobleman of the Zhou dynasty whose territory included the Shanghai area

The city has had various nicknames in English, including "Paris of the East," "Queen of the Orient" (or "Pearl of the Orient"), and even "The Whore of Asia" (a reference to corruption in the 1920s and 1930s, including vice, drugs and prostitution).

Geography and Climate

Shanghai faces the East China Sea (part of the Pacific Ocean) and is bisected by the Huangpu River. Puxi contains the city proper on the western side of Huangpu River, while an entirely new financial district has been erected on the eastern bank of the Huangpu in Pudong.

Shanghai experiences all four seasons, with freezing temperatures during the winter season and an average high of 32 degrees C (90 degrees F) during the hottest months of July and August. Temperatures extremes of -10 C (14 F) and +41 C (105 F) have been recorded. Heavy rain is frequent in early summer. Spring starts in March, summer in June, autumn in September and winter in December. The weather in spring, although it is considered the most beautiful season, is highly variable, with frequent rain and alternating spells of warmth and cold. Summer, the peak tourist season, is hot and oppressive, with very high humidity. Autumn is generally sunny and dry, and the foliage season is in November. Winters are typically grey and dreary, with a few snowfalls. The city has a few typhoons every year, none of which in recent years have caused significant damage.

History

Early Dynastic Era

Until the nineteenth century, Shanghai was not a major city, and in contrast to other major Chinese cities, has only a few ancient Chinese landmarks. Shanghai was founded in the tenth century. The city is located in a swampy area east of Suzhou which was only recently irrigated, although other parts of the Yangtze valley saw irrigation as much as 1,500 years ago. Until 1127, Shanghai was a small fishing village and market town of 12,000 households. That year, however the city grew to 250,000 inhabitants as Kaifeng was conquered and many refugees came to Shanghai.

During the thirteenth century Shanghai and the surrounding area became a cotton production and manufacturing center and one of China's richest regions. The processing of cotton was done using a cotton gin similar to the one invented by Eli Whitney. Cotton cloth remained the mainstay of Shanghai's economy until the early nineteenth century. During Song and Yuan China canals, dikes and real estate were financed with private capital.

The autocratic government of the Ming dynasty (1368–1644) imposed tight trade restrictions. In the sixteenth century, to guard against Japanese and Chinese pirates (Wokou), foreign trade by private merchants was forbidden. After pirates pillaged Shnaghai and killed one hundred merchants, the Ming government evacuated the entire coastal population to the interior. In 1554, a wall was built to protect the city.

Qing Era (1644-1911)

During the early nineteenth century Shanghai reached an economic peak. Under the Qing Dynasty, in the absence of stringent government control, local associations used their provincial networks to control the city and competed with each other in trade. Bankers from different local associations began to cooperate with each other in the Shanghai Native Bankers Guild, using a democratic decision-making process. Trade routes reached as far as Polynesia and Persia, with cotton, silk, and fertilizer as primary exports.

Shanghai’s strategic position at the mouth of the Yangtze River (or Cháng Jiāng, Long River) made it an ideal location for trade with the West, and during the nineteenth century its role changed radically. During the First Opium War in the early-nineteenth century]], British forces temporarily held Shanghai. The war ended with the Treaty of Nanjing in 1842, which opened several treaty ports, including Shanghai, for international trade. The opium imported to China by the United Kingdom essentially destroyed the cotton industry of Shanghai. The Treaty of the Bogue signed in 1843, and the Sino-American Treaty of Wangsia signed in 1844 together gave foreign nations extraterritoriality on Chinese soil, which officially lasted until 1943 but was functionally defunct by the late 1930s, and opened a floodgate to western culture and influence in Shanghai.

In 1850, the Taiping Rebellion broke out. By 1853, Shanghai was occupied by a triad offshoot of the rebels called the “Small Swords Society.” The fighting which devastated the countryside left the foreign settlements untouched, and many Chinese arrived seeking refuge. Although previously Chinese had been forbidden to live in foreign settlements, new regulations in 1854 made land available to Chinese. Land prices rose substantially, and real estate development became a source of considerable income for Shanghai's westerners, further increasing their dominance of the city's economy.

The Shanghai Municipal Council, created to manage the foreign settlements, held its first annual meeting in 1854. In 1863, the British settlement, located along the western bank of the Huangpu river to the south of Suzhou Creek in the Huangpu district, and the American settlements, located on the western bank of the Huangpu river and to the north of Suzhou creek, joined to form the International Settlement. The French opted out of the Shanghai Municipal Council, and instead maintained their own French Concession, located to the south of the International Settlement.

The Sino-Japanese War, fought in 1894-1895 over control of Korea, concluded with the Treaty of Shimonoseki, which established Japan as an additional foreign power in Shanghai. Japan built the first factories there, and these were soon copied by other foreign powers, initiating the development of industry in Shanghai. Two cities emerged: a chaotic Chinese city, and a Western city, inhabited mainly by Chinese. The Western part of Shanghai was one of the most modern "European" cities in the world. New inventions like electricity and trams were quickly introduced, and westerners turned Shanghai into a huge metropolis. British and American businessmen made a great deal of money in trade and finance, and Germany used Shanghai as a base for investing in China. Shanghai accounted for half of the imports and exports of China. Early in the twentieth century, the Western part of Shanghai was four times larger then the Chinese part.

European and American inhabitants of Shanghai called themselves the Shanghailanders. The extensive public gardens along the waterfront of the International Settlement were reserved for the foreign communities and forbidden to Chinese. The foreign city was built in the British style, with a large racetrack west of the city, now People's Park. A new class emerged, the compradors, which mixed with the local landlords to form a new Chinese bourgeoisie. The compradors were indispensable mediators and negotiators for the Western companies doing business with the Chinese. Many compradors were leaders of the movement to modernize China. Shanghai became the largest financial center in the Far East.

Chinese society during this period was divided in local associations or provincial guilds, each with its own style of dress and sub-culture. Society was controlled by these associations. The Guangdong local associations represented the skilled workers of Shanghai, and belonged to the top level of Shanghai society. Ningbo and Jiangsu local associations, representing the common workers, were the most numerous. The Chinese who came from the north were on the bottom rung of society, and many of them were forced to work as seasonal workers or mobsters.

A neutral organization, the Tong Reng Tan, tried to build up good governance in Shanghai. In 1905, the Tong Reng Tan was abolished and replaced by the municipality of Shanghai municipality. A Shanghai local association called the Tongrengtang tongxianghui came into being A series of institutional reforms, called the Self-Strengthening Movement attempted to strengthen the Qing Dynasty by adopting Western innovations, but its success was hampered by the incompetence, corruption and inefficiency of many participants.

Early Republic of China (1912-1937)

In 1912, the Xinhai Revolution brought about the establishment of the Republic of China, and Shanghai became the focal point of activities that would eventually shape modern China. In 1936, Shanghai was one of the largest cities in the world, with three million inhabitants. Only 35,000 of these were foreigners, though they controlled half the city. Russian refugees who came to Shanghai were regarded as an inferior race.

Shanghai Grand

During this period, Shanghai was known as "The Paris of the East, the New York of the West"[6]. Shanghai was made a special city in 1927, and a municipality in May 1930. The city's industrial and financial power increased under the merchants who were in control of the city, while the rest of China was divided among warlords. Shanghai flourished as an entertainment center, and became the headquarters of Chinese cinema and popular music. The architectural style of this period was modeled on British and American design. Many of the large-scale buildings in The Bund, such as Shanghai Club, Asia Building and HSBC building were constructed or renovated at this time, creating a distinct image that set Shanghai apart from the other Chinese cities that preceded it. The city became the commercial center of East Asia, attracting banks from all over the world.

Power Struggle

During the 1920s, Shanghai was also a center for opium smuggling, both domestic and international. The Green Gang (Quinbang) became a major influence in the Shanghai International Settlement, with the Commissioner of the Shanghai Municipal Police reporting that corruption associated with the trade had affected a large proportion of his force. An extensive crackdown in 1925 simply displaced the focus of the trade to the neighboring French Concession.

Meanwhile, the traditional division of society into local associations was falling apart. The new working classes were not prepared to listen to the bosses of the local associations which had dominated during the first decade of the twentieth century. Resentment towards the foreign presence in Shanghai rose among both the entrepreneurs and the workers. In 1919, protests by the May Fourth Movement against the Treaty of Versailles led to the rise of a new group of philosophers like Chen Duxiu and Hu Shi who challenged Chinese traditionalism with new ideologies. The new revolutionary thinking convinced many that the existing government was largely ineffective. The Communist Party of China was founded in 1921.

In 1927, communists tried to end foreign rule, officially supported by the gangsters and the Kuomintang nationalists. In Shanghai, however, leaders of the Green Gang, entered into informal alliances with Chiang Kai-shek, and the capitalists of Shanghai acted against the communists and the organized labor unions. The nationalists had cooperated with gang leaders since the revolution of 1911, and there had been sporadic outbursts of fighting between gangsters and communists. Many communists were killed in a major surprise attack by gangsters on April 12, 1927, in the Chinese-administered part of Shanghai, and Zhou Enlai fled the city.

Chiang Kai-shek started an autocratic rule which lasted from 1927 to 1937, supported by the progressive local associations, each of which consisted of workers, businessmen, gangsters and others who had originated from a specific province. The effort to organize society into corporations failed because only a minority of the Chinese agreed to join the local associations, and Chiang Kai-shek resorted to the assistance of gangsters in maintaining his grip on Chinese society. Chiang Kai-shek’s nationalist government made Shanghai their capital, building large modern Chinese residential areas, with good roads and parking lots for automobiles, north of the foreign concessions. A new Chinese port was built, which could compete with the Europeans’ port. Chiang Kai-shek continuously requested large amounts of money from Shanghai financiers for his projects. Some bankers and merchants resisted from the start, while others were so enthusiastic in supporting the KMT that they liquidated their companies to contribute as much money as possible. At first most bankers and merchants were willing to invest in the army, but in 1928 they refused to subsidize it any longer. Chiang began to nationalize all enterprises.

In the early 1930s, the power of the gangsters increased. Green Gang-leader Du Yuesheng. Du started his own local association. When mobsters stormed the Shanghai Stock Exchange, the police did not interfere because they had been dominated by the mobsters since 1919. The Westerners did not interfere either, considering this to be an internal Chinese affair, and the nationalist government did not interfere because it wished to weaken the power of the entrepreneurs. After a second attack on the Stock Exchange, the entrepreneurs and businessmen were forced to negotiate a deal with the mobsters.

World War II and the Japanese Occupation

The Japanese Navy bombed Shanghai on January 28, 1932, ostensibly to crush the protests of Chinese student against the Manchurian Incident and the subsequent Japanese occupation. The Chinese fought back in what was known as the January 28 Incident. The two sides fought to a standstill and a ceasefire was brokered in May. During the Second Sino-Japanese War, the city fell after the Battle of Shanghai in 1937, and was occupied until Japan's surrender in 1945.

During World War II in Europe, Shanghai became a center for European refugees. It was the only city in the world that was open unconditionally to the Jews at the time. However, in late 1941, under pressure from their allies, the Nazis, the Japanese confined the Jewish refugees in what came to be known the Shanghai ghetto, and hunger and infectious diseases such as amoebic dysentery became rife. The foreign population rose from 35,000 in 1936 to 150,000 in 1942, mainly due to the Jewish refugees. The Japanese were harsher on the British, Americans, and Dutch, who slowly lost their privileges and were required to wear a B, A, or N for their nationality when walking in public places. Their villas were turned into brothels and gambling houses, and in 1943, British, Americans, and Dutch residents of Shanghai were force-marched to Japanese concentration camps.

End of Foreign Concessions

The major Shanghai companies which had come under the control of the Kuomintang government had become corrupt after moving to inland China in 1937. In 1946, when the French departed, the foreign concessions in Shanghai were closed. Shanghai merchants and bankers had lost faith that the Kuomintang government could maintain a healthy economy in Shanghai. The nationalist government had no concern for local interests in Shanghai and attempted to impose an autocratic rule. The foreigners who had provided protection for the gangs were gone, and they were now ignored by the nationalist government. Du Yuesheng tried to become the mayor of Shanghai, but was forced to leave the city. Communists gained control over the workers by forming broad coalitions in place of the smaller local associations.

Tightened Communist rule (1949-1980s)

On May 27, 1949, Shanghai came under the control of the Communist Party of China, and along with Beijing, was one of the only two former Republic of China municipalities not merged into neighboring provinces over the next decade. The boundaries of its subdivisions underwent several changes. The communists conducted mass executions of thousands of “counter-revolutionaries,” and places such as the Canidrome were transformed from elegant ballrooms to mass execution facilities[7][8]. The communist party continues to express the common view that the city was taken over in a "peaceful" manner and to censor historical accounts, though numerous Western texts accounts describe the violence that occurred when the People's Liberation Army marched into the city. [8]. Most foreign firms moved their offices from Shanghai to Hong Kong, and large numbers of emigrants settled in the North Point area, which came to be known as "Little Shanghai"[9].

During the 1950s and 1960s, Shanghai became an industrial center and a center of revolutionary left-wing politics. Economically, the city made little or no progress during the Maoist era and the Cultural Revolution, but even during the most tumultuous times, Shanghai was able to maintain relatively high economic productivity and social stability. Through almost the entire history of the Peoples Republic of China, Shanghai was the largest contributor of tax revenue to the central government, at the cost of severely crippling Shanghai's infrastructure, capital and artistic development. Because of Shanghai’s importance to China's fiscal well-being, the city was denied economic liberalizations, and Shanghai was not permitted to initiate economic reforms until 1991.

Economic and Cultural Rebound (1990s - Present)

Political power in Shanghai has traditionally been seen as a stepping stone to higher positions within the PRC central government. During the 1990s, there existed what was often described as the politically right-of-center "Shanghai clique," which included the president of the PRC Jiang Zemin and the premier of the PRC Zhu Rongji. Beginning in 1992, the central government under Jiang Zemin, a former Mayor of Shanghai, began reducing the tax burden on Shanghai and encouraging both foreign and domestic investment, in order to promote it as an economic hub of East Asia and to promote its role as a gateway to investment in the Chinese interior. Since then it has experienced continuous economic growth of between 9–15 percent annually, possibly at the expense of growth in Hong Kong, leading China's overall development.

Economy and Demographics

Shanghai is the financial and trade center of the Peoples Republic of China. It began economic reforms in 1992, a decade later than many of the Southern Chinese provinces. Prior to then, most of the city’s tax revenues went directly to Beijing, with little remaining for the maintenance of local infrastructure. Even with a decreased tax burden after 1992, Shanghai's tax contribution to the central government is around 20 percent - 25 percent of the national total. Before the 1990s, Shanghai's annual tax burden was an average of 70 percent of the national total. Today, Shanghai is the biggest and most developed city in mainland China.

The 2000 census put the population of Shanghai Municipality at 16.738 million, including the floating population, which made up 3.871 million. Since the 1990 census the total population has increased by 3.396 million, or 25.5 percent. Males accounted for 51.4 percent, females for 48.6 percent of the population. The age group of 0-14 made up 12.2 percent, 76.3 percent between 15 and 64, and 11.5 percent were older than 65. The illiteracy rate was 5.4 percent. As of 2003, the official registered population was 13.42 million; however, more than 5 million more people work and live in Shanghai undocumented, and of that 5 million, some 4 million belong to the floating population of temporary migrant workers. The average life expectancy in 2003 was 79.80 years, 77.78 for men and 81.81 for women.

Shanghai and Hong Kong have recently become rivals over which city is to be the economic center of China. Shanghai had a GDP of ¥46,586 (ca. US$ 5,620) per capita in 2003, ranked 13 among all 659 Chinese cities. Hong Kong has the advantage of a stronger legal system and greater banking and service expertise. Shanghai has stronger links to both the Chinese interior and the central government, in addition to a stronger base of manufacturing and technology. Since the handover of Hong Kong to the PRC in 1997, Shanghai has increased its role in finance, banking, and as a major destination for corporate headquarters, fueling demand for a highly educated and modernized workforce. Shanghai's economy is steadily growing at 11 percent and for 2004 the forecast is 14 percent.

Shanghai is increasingly a critical center of communication with the Western world. One example is the Pac-Med Medical Exchange, a clearinghouse of medical data and a link between the Chinese and westernized medical infrastructures, which opened in June, 2004. The Pudong district of Shanghai contains intentionally westernized streets (European/American 'feeling' districts) in close proximity to major international trade and hospitality zones. Western visitors to Shanghai are greeted with free public parks, manicured to startling perfection, in distinct contrast to the massive industrial installations which reveal China's emerging environmental concerns. For a densely populated urban center and international point of trade, Shanghai is generally free of crime against its visitors; Shanghai's international diversity is perhaps the world's foremost window into the rich, historic and complex society of today's China.

Architecture

As in many other areas in China, Shanghai is undergoing a building boom. In Shanghai the modern architecture is notable for its unique style, especially on the highest floors, with several restaurants which resemble flying saucers on the top floors of tall buildings.

One uniquely Shanghainese cultural element is the Shikumen (石库门, 石庫門, "stone gate") residencies. The Shikumen is a cultural blend of the elements found in Western architecture with traditional Lower Yangtze Chinese architecture and social behavior. Two or three-storey black or gray brick residences, cut across with a few decorative dark red stripes, are arranged in straight alleys, with the entrance to each alley, the gate, wrapped by a stylistic stone arch. The roofless courtyard at the center of traditional Chinese dwellings was made much smaller to provide each residence with an "interior haven" from the commotions in the streets, where rain could fall and vegetation could grow. The courtyard also allowed sunlight and adequate ventilation into the rooms. The style originally developed when local developers adapted terrace houses to Chinese conditions. The wall was added to protect against fighting and looting during the Taiping rebellion, and later against burglars and vandals during the social upheavals of the early twentieth century. By World War II, more than 80 percent of the population in the city lived in these kinds of dwellings. Many were hastily built and were akin to slums, while others were of sturdier construction and featured modern amenities such as flush toilets. During and after World War II, massive population increases in Shanghai led to the extensive subdivision of many shikumen houses. The spacious living room is often divided into three or four rooms, each rented out to a family. These cramped conditions continue to exist in many of the shikumen districts that have survived recent development.

The tallest structure in China, the distinctive Oriental Pearl Tower, is located in Shanghai. Living quarters in its lower sphere are now available for very high prices. The Jin Mao tower, located nearby, is mainland China's tallest skyscraper, and the fifth tallest building in the world.

Transportation

Shanghai has an excellent public transportation system and, in contrast to other major Chinese cities, has clean streets and surprisingly little air pollution.

The public transportation system in Shanghai is flourishing: Shanghai has more than one thousand bus lines and the Shanghai Metro (subway) has five lines (numbers 1, 2, 3, 4, 5) at present. According to the development schedule of the Government, by the year 2010, another eight lines will be built in Shanghai.

Shanghai has two airports: Hongqiao and Pudong International, which has the second highest (combined) traffic next only to Hong Kong Airport in China. Transrapid (a German magnetic levitation train company, constructed the first operational maglev railway in the world, from Shanghai's Long Yang Road subway station to Pudong International Airport. It was inaugurated in 2002,and began to be used commercially in 2003. It takes 7 minutes and 21 seconds to travel 30 kilometers, and reaches a maximum speed of 431 kilometers per hour.

As of 2004, Shanghai's port is the largest in the world.

Three railways intersect in Shanghai: Jinghu Railway (京沪线 Beijing-Shanghai Line) which passes through Nanjing, Shanghai-Hangzhou Railway (沪杭线 Hu Hang Line), and Xiaoshan-Ningbo (萧甬线 Xiao Yong Line). Shanghai has three passenger railway stations, Shanghai Railway Station, Shanghai West Railway Station and Shanghai South Railway Station.

Expressways from Beijing (Jinghu Expressway) and from the region around Shanghai liaise with the city. There are ambitious plans to build expressways to connect Chongming Island. Shanghai's first ring road expressway is now complete. Within Shanghai itself, there are elevated highways, and tunnels and bridges are used to link Puxi to Pudong.

People and Culture

The vernacular language is Shanghainese, a dialect of Wu Chinese; while the official language is Standard Mandarin. The local dialect is mutually unintelligible with Mandarin, but is an inseparable part of the identity of Shanghai.. Nearly all Shanghai residents under the age of 50 can speak Mandarin fluently; and those under the age of 25 have had contact with English since primary school.

Shanghai is seen as the birthplace of everything considered modern in China; and was the cultural and economic center of East Asia for the first half of the twentieth century. It became an intellectual battleground between socialist writers, who concentrated on critical realism (pioneered by Lu Xun and Mao Dun), and more romantic and aesthetic writers such as Shi Zhecun, Shao Xunmei, Ye Lingfeng, and Eileen Chang.

Besides literature, Shanghai was also the birthplace of Chinese cinema. China’s first short film, The Difficult Couple (Nanfu Nanqi, 1913), and the country’s first fictional feature film, Orphan Rescues Grandfather (Gu-er Jiuzu Ji, 1923), were both produced in Shanghai. Shanghai's film industry went on to blossom during the early 1930s, generating Marilyn Monroe-like stars such as Zhou Xuan, who committed suicide in 1957. The talent and passion of Shanghai filmmakers following World War II and the Communist Revolution contributed substantially to the development of the Hong Kong film industry.

The residents of Shanghai have often been stereotyped by other Chinese peoples as being pretentious, arrogant, and xenophobic. They are also admired for their meticulous attention to detail, adherence to contracts and obligations, and professionalism. Nearly all registered Shanghai residents are descendants of immigrants from the two adjacent provinces of Jiangsu and Zhejiang, regions that generally speak the same family of Wu Chinese dialects. Much of pre-modern Shanghai culture was an integration of cultural elements from these two regions. The Shanghainese dialect reflects this as well. Recent migrants into Shanghai, however, come from all over China, do not speak the local dialect and are therefore forced to use Mandarin as a lingua franca. Rising crime rates, littering, harassive panhandling, and an overloading of the basic infrastructure, especially of public transportation and schools, associated with the rise of these migrant populations (over three million new migrants in 2003 alone) have been generating a degree of ill will and xenophobia from longtime residents of Shanghai. The new migrants are often targets of both intentional and unintentional discrimination, contributing to cultural misunderstandings and stereotyping. It is a common Chinese stereotype that the men of Shanghai are henpecked, nagged, and controlled by their wives.

Shanghai cultural artifacts include the cheongsam, a modernization of the traditional Chinese/Manchurian qipao garment, which first appeared in the 1910s in Shanghai. The cheongsam dress was slender with high cut sides, and tight fitting, in sharp contrast to the traditional qipao which was designed to conceal the figure and be worn regardless of age. The cheongsam went along well with the Western overcoat and the scarf, and portrayed an unique East Asian modernity, epitomizing the Shanghai population. As Western fashions changed, the basic cheongsam design changed, too, to include high-necked sleeveless dresses, bell-like sleeves and black lace frothing at the hem of a ball gown. By the 1940s, cheongsams came in transparent black, beaded bodices, matching capes and even velvet. Later, checked fabrics became common. The 1949 Communist Revolution ended the wearing of cheongsam and other fashions in Shanghai. However, Shanghai styles have recently been revived as stylish party dresses.

Much of the Shanghai culture was transferred to Hong Kong by the millions of emigrants and refugees after the Communist Revolution. The movie In the Mood for Love (Hua Yang Nian Hua) directed by Wong Kar-wai (a native of Shanghai himself) depicts one slice of the displaced Shanghai community in Hong Kong and the nostalgia for that era, featuring 1940s music by Zhou Xuan.

Cultural sites in Shanghai include:

- The Bund

- Shanghai Museum

- Shanghai Grand Theatre

- Longhua temple]], largest temple in Shanghai, built during the Three Kingdoms period

- Yuyuan Gardens

- Jade Buddha Temple

- Jing An Temple

- Xujiahui Cathedral, largest Catholic cathedral in Shanghai

- Dongjiadu Cathedral

- She Shan Cathedral

- The Orthodox Eastern Church

- Xiaotaoyuan (Mini-Peach Orchard) Mosque

- Songjiang Mosque

- Ohel Rachel Synagogue

- Lu Xun Memorial

- Shikumen site of the First CPC Congress

- Residence of Sun Yat-sen

- Residence of Chiang Kai-shek

- Shanghai residence of Qing Dynasty Viceroy and General Li Hongzhang

- Ancient rivertowns of Zhujiajiao and Zhoushi on the outskirts of Shanghai

- Wen Miao Market

- Yunnan Road, Shanghai|Yunnan Road

- Flowers and birds: Jiang yi lu market

- Cheongsam: Chang le lu Cheongsam Street

- Curio Market: Dong Tai Lu Curio Market

- Shanghai Peking Opera Troupe

Colleges and universities

National

- Shanghai Jiao Tong University (founded in 1896)

- Medical School of Shanghai Jiaotong University] (formerly Shanghai Second *Medical School, founded in 1896)

- Fudan University (founded in 1905)

- Fudan University Shanghai Medical College (formerly Shanghai Medical University, founded in 1927)

- Tongji University (founded in 1907)

- East China Normal University

- East China University of Science and Technology

- Donghua University

- Shanghai International Studies University

- Shanghai University of Finance and Economics

- CEIBS|China Europe International Business School

Public

- Second Military Medical University

- Shanghai Teachers University

- East China University of Politics and Law

- Shanghai Conservatory of Music

- Shanghai Theater Academy

- Shanghai University

- Shanghai Maritime University

- Shanghai University of Electric Power

- University of Shanghai for Science and Technology

- Shanghai University of Engineering Sciences

- Shanghai Institute of Technology

- Shanghai Fisheries University

- Shanghai Institute of Foreign Trade

- Shanghai Institute of Physical Education

Private

- Sanda University

Shanghai in Fiction

Literature

Han Bangqing (Shanghai Demi-monde, or Flowers of Shanghai) is a novel that follows the lives of Shanghai flower girls and the timeless decadence surrounding them. It was first published in 1892 during the last two decades of the Qing Dynasty, with the dialog completely in vernacular Wu Chinese. The novel set a precedent for all Chinese literature and was highly popular until the standardization of vernacular Standard Mandarin as the national language in the early 1920s. It was later translated into Mandarin by Eileen Chang, a famous Shanghai writer during World War II. Nearly all her works of bourgeois romanticism are set in Shanghai, and many have been made into arthouse films (see Eighteen Springs).

Besides Chang, other Shanghai "petit bourgeois" writers in the first half of the twentieth century were Shi Zhecun, Liu Na'ou and Mu Shiyang, Shao Xunmei and Ye Lingfeng. Socialist writers include: Mao Dun (famous for his Shanghai-set Ziye), Ba Jin, and Lu Xun. One of the great Chinese novels of the twentieth century, Qian Zhongshu's Fortress Besieged, is partially set in Shanghai.

Noel Coward wrote his novel Private Lives while staying at Shanghai's Cathay Hotel.

André Malraux published his novel La Condition Humaine (Man's Fate), in 1933 about the defeat of a communist regime in Shanghai and the choices the losers have to face. Malraux won the Prix Goncourt of literature that year for the novel.

Tom Bradby's 2002 historical detective novel The Master of Rain is set in the Shanghai of 1926. Neal Stephenson's science fiction novel The Diamond Age is set in an ultra-capitalist Shanghai of the future.

Films Featuring Shanghai

- Godzilla: Final Wars (2004), in which Anguirus attacks the city and destroys the Oriental Pearl Tower

- Kung Fu Hustle (Gong Fu, 2004), directed by Stephen Chow

- Code 46 (2003), directed by Michael Winterbottom

- Purple Butterfly[10] (Zihudie, 2003), directed by Ye Lou

- Suzhou River (Suzhou he, 2000), directed by Ye Lou

- Flowers of Shanghai[11] (Hai shang hua, 1998), directed by Hou Hsiao-Hsien

- A Romance in Shanghai (1996), starring Fann Wong.

- Shanghai Triad (Yao a yao yao dao waipo qiao, 1995), directed by Zhang Yimou

- Eighteen Springs[12] (Ban sheng yuan, 1998), directed by Ann Hui On-wah.

- Fist of Legend (Jing wu ying xiong, 1994), action movie starring Jet Li, a remake of Fist of Fury.

- Empire of the Sun (1987), directed by Steven Spielberg

- Le Drame de Shanghaï (1938), directed by Georg Wilhelm Pabst, filmed in France and in Saigon

- Shanghai Express[13] (1932), starring Marlene Dietrich

- A Great Wall (1986), directed by Peter Wang

Notes

- ↑ Land Area. Basic Facts. Shanghai Municipal Government. Retrieved May 25, 2012.

- ↑ Water Resources. Basic Facts. Shanghai Municipal Government. Retrieved May 25, 2012.

- ↑ Topographic Features. Basic Facts. Shanghai Municipal Government. Retrieved May 25, 2012.

- ↑ Communiqué of the National Bureau of Statistics of People's Republic of China on Major Figures of the 2010 Population Census. National Bureau of Statistics of China. Retrieved May 25, 2012.

- ↑ "上海人均GDP超北京全国最高", 20 January 2012. (written in Chinese) Retrieved May 25, 2012.

- ↑ Concierge Traveler. Concierge. Shanghai Shadows. Retrieved April 22, 2008.

- ↑ Time Magazine. Kill nice!. Retrieved April 22, 2008.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Lucille Bellucci, 2005, Journey from Shanghai. iUniverse Publishing. ISBN 0595343732

- ↑ Jason Wordie, Jason, 2002, Streets: Exploring Hong Kong Island. Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press. ISBN 9622095631

- ↑ Purple Butterfly, Nielsen Business Media, Inc. Retrieved April 22, 2008.

- ↑ Flowers of Shanghai, IMDC.com, Inc. Retrieved April 22, 2008.

- ↑ Eighteen Springs, Shelly Kraicer. Retrieved April 22, 2008.

- ↑ Shanghai Express, IMDB.com, Inc. Retrieved April 22, 2008.

References

ISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Brown, J. D. 2005. Shanghai. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley. ISBN 0764583581 ISBN 9780764583582

- Lu, Hanchao. 1999. Beyond the neon lights everyday Shanghai in the early twentieth century. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 0585288984 ISBN 9780585288987

- Meng, Yue. 2006. Shanghai and the edges of empires. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. ISBN 0816644128 ISBN 0816644136 ISBN 9780816644124 ISBN 9780816644131

- Ross, Andrew. 2006. Fast boat to China: corporate flight and the consequences of free trade : lessons from Shanghai. New York: Pantheon Books. ISBN 037542363X ISBN 9780375423635

- Yeh, Catherine Vance. 2006. Shanghai love: courtesans, intellectuals, and entertainment culture, 1850-1910. Seattle: University of Washington Press. ISBN 0295985674 ISBN 9780295985671

External links

All links retrieved January 27, 2023.

|

|||||||||||||||||

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.

↧ Download as ZWI file | Last modified: 02/04/2023 04:04:44 | 320 views

☰ Source: https://www.newworldencyclopedia.org/entry/Shanghai,_China | License: CC BY-SA 3.0

ZWI signed:

ZWI signed:

KSF

KSF