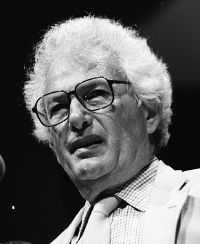

Joseph Heller

From Nwe

From Nwe

Joseph Heller |

|

| Born: | May 1, 1923 Brooklyn, New York City |

|---|---|

| Died: | December 13, 1999 East Hampton, NY |

| Occupation(s): | novelist |

| Nationality: | United States |

| Literary genre: | fiction |

| Magnum opus: | Catch-22 |

| Influenced: | Robert Altman |

Joseph Heller (May 1, 1923 – December 12, 1999) was an American satirist best remembered for writing the satiric World War II classic novel Catch-22. The literary devices established in this first novel continued in his other books. The book was partly based on Heller's own experiences. The phrase "Catch-22" has entered the English language to signify a no-win situation, particularly one created by a law, regulation or circumstance.

Heller is widely regarded as one of the best post-World War satirists. Although he is remembered mostly by his landmark Catch 22, his works, centered on the lives of various members of the middle-classes, remain exceptional exemplars of modern satire. His writings influenced, among others, Robert Altman's comedy M*A*S*H and the subsequent TV series, set in the Korean War.

Biography

(1923-1960) Early life and pre-Catch-22 occupations

Heller was born in Brooklyn, New York, as the son of poor Jewish parents. His Russian-born father, Isaac Heller, who was a bakery truck driver, died in 1927 due to a botched ulcer operation. After graduating from Abraham Lincoln High School in 1941, Heller joined the Twelfth Air Force. He was stationed in Corsica, where he flew 60 combat missions as a B-25 bombardier. In 1949 Heller received his M.A. from Columbia University. He was a Fulbright scholar at Oxford University in 1949-1950. Heller taught English composition under a regimen for two years at Pennsylvania State University (1950-52), before moving on to become a copywriter for the magazines Time (1952-1956) and Look (1956-1958), before becoming promotion manager for McCall's. He left McCall's in 1961 to teach fiction and dramatic writing at Yale University and the University of Pennsylvania.

(1961-1970) Catch-22

- "All over the world, boys on every side of the bomb line were laying down their lives for what they had been told was their country, and no one seemed to mind, least of all the boys who were laying down their young lives. There was no end in sight" (Catch-22).

Heller sold his first stories as a student. They were published in such magazines as Atlantic Monthly and Esquire. In the early 1950s he started working on Catch-22. At that time Heller was employed as a copywriter at a small advertising agency. He wrote most of the book in the foyer of a West End Avenue apartment. Heller wrote, in Now and Then, published in 1998, "As I've said and repeat, I wrote the first chapter in longhand one morning in 1953, hunched over my desk at the advertising agency (from ideas and words that had leaped into my mind only the night before); the chapter was published in the quarterly New World Writing #7 in 1955 under the title 'Catch-18.' (I received twenty-five dollars. The same issue carried a chapter from Jack Kerouac's On the Road, under a pseudonym.)" The novel went largely unnoticed until 1962, when its English publication received critical praise. And in The New York World-Telegram Richard Starnes opened his column with the prophetic words: "Yossarian will, I think, live a very long time." An earlier reviewer called the book "repetitious and monotonous," and another "dazzling performance that will outrage nearly as many readers as it delights."

Catch-22 was not a success when first published, but a few months later S. J. Perelman praised the book in an interview; soon afterward, sales figures took off, and this novel has enjoyed steady sales ever since. Mike Nichols's movie version of the novel from 1970 is considered disappointing. Nichols emphasized the absurdity of war, and as Heller, he rejected American militarism. Orson Welles, who also was interested in filming the book, played the role of General Dreedle. After writing Catch-22, Heller worked on several Hollywood screenplays, such as Sex and the Single Girl, Casino Royale, and Dirty Dingus Magee, and contributed to the TV show McHale's Navy under the pseudonym Max Orange. In the 1960s Heller was involved with the Vietnam War protest movement.

Catch 22 controversy

In April 1998, Lewis Pollock wrote to the Sunday Times of London asking for clarification as to "the amazing similarity of characters, personality traits, eccentricities, physical descriptions, personnel injuries and incidents" in Catch 22 and a novel published in England in 1951. The book that spawned the request was written by Louis Falstein and titled The Sky is a Lonely Place in Britain and Face of a Hero in the United States. Falstein's novel was available two years before Heller wrote the first chapter of Catch 22 (1953) while he was a student at Oxford. The Times stated "Both have central characters who are using their wits to escape the aerial carnage; both are haunted by an omnipresent injured airman, invisible inside a white body cast," Heller replied to the controversy in a piece for the Washington Post. "My book came out in 1961[;] I find it funny that nobody else has noticed any similarities, including Falstein himself, who died just last year" (April 27, 1998).

(1974-2000) Other works

Heller waited 13 years before publishing his next novel—the darker and more sombre Something Happened (1974). It portrayed a corporation man, Bob Slocum, who suffers from insomnia and almost smells the disaster mounting toward him. Slocum's life is undramatic, but he feels that his happiness is threatened by unknown forces. "When an ambulance comes, I'd rather not know for whom." He does not share Yossarian's rebelliousness, but he acts cynically as a "wolf among a pack of wolves." Heller's play-within-a-play, We Bombed in New Haven (1968), was written in part to express his protest against the Vietnam war. It was produced on Broadway and ran for 86 performances. Catch-22 has also been dramatized. It was first performed at the John Drew Theater in East Hampton, New York, on July 13, 1971.

Heller's later works include Good As Gold (1979), where the protagonist Bruce Gold tries to regain the Jewishness he has lost. Readers hailed the work as a return to puns and verbal games familiar from Heller's first novel. God Knows (1984) was a modern version of the story of King David and an allegory of what it is like for a Jew to survive in a hostile world. David has decided that he has been given one of the best parts of the Bible. "I have suicide, regicide, patricide, homicide, fratricide, infanticide, adultery, incest, hanging, and more decapitations than just Saul's."

No Laughing Matter (1986), written with Speed Vogel, was a surprisingly cheerful account of Heller's experience as a victim of Guillain-Barré syndrome. During his recuperation Heller was visited among others by Mario Puzo, Dustin Hoffman and Mel Brooks. His next book, published in 1988, was the satirical and experimental historical fiction Picture This. In 1994, he returned with Closing Time a sequel to Catch-22 depicting the current lives of its heroes. Yossarian is now 40 years older and as preoccupied with death as in the earlier novel. "Thank God for the atom bomb," says Yossarian. Now and Then: From Coney Island to Here (1998) is Heller's autobiographical work, evocation of his boyhood home, Brooklyn's Coney Island in the 1920s and 1930s. Heller comments, "It has struck me since—it couldn't have done so then—that in Catch-22 and in all my subsequent novels, and also in my one play, the resolution at the end of what narrative there is evolves from the death of someone other than the main character."

Heller had two children by his first marriage. His divorce was recounted in No Laughing Matter. In 1989 Heller married Valerie Humphries, a nurse he met while ill. Heller died of a heart attack at his home in East Hampton, New York on December 13, 1999. His last novel, Portrait Of The Artist As An Old Man (2000), published posthumously, was about a successful novelist who seeks an inspiration for his book. "A lifetime of experience had trained him never to toss away a page he had written, no matter how clumsy, until he had gone over it again for improvement, or had at least stored it in a folder for safekeeping or recorded the words on his computer."[1]

Catch 22

Plot introduction

The novel follows Captain John Yossarian, a fictional United States Army Air Force B-25 bombardier, and a number of other characters during World War II. Most events in the book occur while the airmen of the Fighting 256th (or "two to the fighting eighth power") Squadron are based on the island of Pianosa, west of Italy. Many events in the book are described repeatedly from differing points of view, so that the reader learns more about the event with each iteration. The pacing of Catch-22 is frenetic, its tenor is intellectual, and its humor is largely absurd, but with grisly moments of realism interspersed.

Explanation of the novel's title

A magazine excerpt from the novel was originally published as Catch-18, but Heller's publisher requested that he change the title of the novel so it wouldn't be confused with another recently published World War II novel, Leon Uris's Mila 18. The number 18 has special meaning in Judaism and was relevant to early drafts of the novel which had a somewhat greater Jewish emphasis.[2]

There was a suggestion for the title Catch-11, with the duplicated 1 in parallel to the repetition found in a number of character exchanges in the novel, but due to the release of the original "Rat Pack" movie, Ocean's Eleven, this was also rejected. Catch-14 was also rejected apparently because the publisher did not feel that 14 was a "funny number." So eventually the title came to be Catch-22, which like 11 has a duplicated digit with the 2 also referring to a number of déjà vu like events common in the novel.[2]

The concept

Catch-22 is, among other things, a general critique of bureaucratic operation and reasoning. As a result of its specific use in the book, the phrase "Catch-22" has come into common use to mean a no-win situation or a double bind of any type. Within the book, "Catch-22" is introduced as a military rule, the self-contradictory circular logic of which, for example, prevents anyone from avoiding combat missions. In Heller's own words:

There was only one catch and that was Catch-22, which

specified that a concern for one's safety in the face of dangers that were real and immediate was the process of a rational mind. (Lieutenant) Orr was crazy and could be grounded. All he had to do was ask; and as soon as he did, he would no longer be crazy and would have to fly more missions. Orr would be crazy to fly more missions and sane if he didn't, but if he was sane he had to fly them. If he flew them he was crazy and didn't have to; but if he didn't want to he was sane and had to. Yossarian was moved very deeply by the absolute simplicity of this clause of Catch-22 and let out a respectful whistle.

- "That's some catch, that Catch-22," he [Yossarian] observed.

- "It's the best there is," Doc Daneeka agreed.

Much of Heller's prose in Catch-22 is circular and repetitive, exemplifying in its form the structure of a Catch-22. Heller revels in the use of paradox. For example, "The Texan turned out to be good-natured, generous and likeable. In three days no one could stand him," and, "the case against Clevinger was open and shut. The only thing missing was something to charge him with." This constantly undermines the reader's understanding of the milieu of the characters, and is key to understanding the book. An atmosphere of logical irrationality pervades the whole description of Yossarian's life in the armed forces, and indeed the entire book.

Other forms of a Catch-22 are invoked at other points in the novel to justify various bureaucratic actions. At one point, victims of harassment by military agents quote the agents as having explained one of Catch-22's provisions in this fashion: Catch-22 states that agents enforcing Catch-22 need not prove that Catch-22 actually contains whatever provision the accused violator is accused of violating. An old woman explains: Catch-22 "says they have a right to do anything we can’t stop them from doing." Yossarian comes to realize that Catch-22 doesn't actually exist, but that because the powers that claim it does and the world believes that it does, it nevertheless has potent effects. Indeed, because it does not really exist there is no way it can be repealed, undone, overthrown, or denounced. The combination of brute force with specious legalistic justification is one of the book's primary motifs.

Major themes

The book portrays the absurdity of living by the rules of others. The world itself is portrayed as insane, so the only practical survival strategy is to be insane oneself. Another theme is the collective folly of patriotism and honor, which leads most of the airmen to accept Catch-22 and the abusive lies of bureaucrats, but which Yossarian never accepts as a legitimate answer to his complaints. While the (official) enemies are the Germans, no German ever actually appears in the story. As the narrative progresses, Yossarian comes to fear American bureaucrats more than he fears the Germans attempting to shoot down his airplane.

Influences

Although Heller had a desire to be an author from an early age, his own experiences a as bombardier over Avignon during World War II strongly influence Catch-22.[3]

Czech writer Arnošt Lustig recounts in his book 3x18, that Joseph Heller personally told him that he would never have written Catch-22 had he not first read The Good Soldier Švejk, the satirical masterpiece of the First World War by Jaroslav Hašek. [4]

There are few references to other works; Moby Dick and Crime and Punishment are among the exceptions. However, there is a pervasive satirical tone toward the Jewish faith and Bible, as demonstrated by the narrator's revealing look at Chaplain Tappman.

So many things were testing his faith. There was the Bible, of course, but the Bible was a book, and so were Bleak House, Treasure Island, Ethan Frome, and The Last of the Mohicans. Did it then seem probable, as he had once overheard Dunbar ask, that the answers to riddles of creation would be supplied by people too ignorant to understand the mechanics of rainfall? Had Almighty God, in all His infinite wisdom, really been afraid that men six thousand years ago would succeed in building a tower to heaven?

Literary significance and criticism

In the preface to Catch-22 from 1994 onwards, Heller points out that the novel raised very polarized views on its first publication in the United States.

Reviews in publications ranged from the very positive to the very negative. The Nation called it "the best novel to come out in years," the New York Herald Tribune said it was a "A wild, moving, shocking, hilarious, raging, exhilarating, giant roller-coaster of a book"[5] and the Orville Prescott of the The New York Times branded it a "dazzling performance that will outrage nearly as many readers as it delights."[6]

On the other hand, the New Yorker was highly critical, saying that it "doesn't even seem to be written; instead, it gives the impression of having being shouted onto paper ... what remains is a debris of sour jokes."[5] Another critic wrote in the New York Times that the book "is repetitive and monotonous. Or one can say that it is too short because none of its many interesting characters and actions is given enough play to become a controlling interest."[7]

Although the novel won no awards upon release, it has remained in print and is seen as one of the most significant American novels of the twentieth century.[8] Scholar and fellow World War II veteran Hugh Nibley said it was the most accurate book he ever read about the military.[9]

Works

Novels

- Catch-22 (1961)

- Something Happened (1974)

- Good As Gold (1979)

- God Knows (1984)

- No Laughing Matter with Speed Vogel (1986)

- Picture This (1988)

- Closing Time (1994)

- Portrait Of The Artist As An Old Man (2000)

Short stories

- Catch As Catch Can: The Collected Stories and Other Writings (2003)

- Three Short Stories Of Utter Annoyance

Autobiographies

- Now and Then: From Coney Island to Here (1998).

Plays

- We Bombed in New Haven (1967)

- Clevinger's Trial (1973)

Quotations

- "When I read something saying I've not done anything as good as Catch-22 I'm tempted to reply, 'Who has?'"

- "Some men are born mediocre, some men achieve mediocrity, and some men have mediocrity thrust upon them."

Notes

- ↑ Joseph Heller, Portrait of an Artist, as an Old Man (Simon & Schuster, 2000, ISBN 978-0743202008).

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 N. James, "The Early Composition History of Catch-22," in Biographies of Books: The Compositional Histories of Notable American Writings, ed. J. Barbour and T. Quirk (Columbia: University of Missouri Press, 1995, ISBN 978-0826210449), 262-290.

- ↑ D.M. Craig, "From Avignon to Catch-22." War, Literature, and the Arts 6(2) (1994): 27-54.

- ↑ A Personal Testimony by Arost Lustig Zenny.com. Retrieved December 19, 2022.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Catch-22: Media reviews Retrieved December 19, 2022.

- ↑ "t Will Outrage As Many Readers As It Delights” On Joseph Heller’s Catch-22 Book Marks, November 10, 2021. Retrieved December 19, 2022.

- ↑ Revisiting the 'Emotional Hodge-Podge' of 'Catch-22' The New York Times, August 28, 2020. Retrieved December 19, 2022.

- ↑ What is Catch-22? And why does the book matter? BBC, March 12, 2002. Retrieved December 19, 2022.

- ↑ Hugh Nibley and Alex Nibley, Sergeant Nibley PhD.: Memories of an Unlikely Screaming Eagle (Salt Lake City: Shadow Mountain, 2006, ISBN 978-1573458450), 255.

References

ISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Barbour, J., and T. Quirk (eds.). Biographies of Books: The Compositional Histories of Notable American Writings. Columbia: University of Missouri Press, 1995. ISBN 978-0826210449

- Bloom, Harold. Joseph Heller's Catch-22. Chelsea House Publications, 2001. ISBN 978-0791059272

- Craig, David M. Tilting at Mortality: Narrative Strategies in Joseph Heller's Fiction. Wayne State University Press, 2000. ISBN 978-0814329122

- Heller, Joseph. Portrait of an Artist, as an Old Man. Simon & Schuster, 2000. ISBN 978-0743202008

- Nibley, Hugh, and Alex Nibley. Sergeant Nibley PhD.: Memories of an Unlikely Screaming Eagle. Salt Lake City: Shadow Mountain, 2006. ISBN 978-1573458450

- Potts, Stephen W. From Here to Absurdity: The Moral Battlefields of Joseph Heller. Borgo Press, 2007. ISBN 978-0893703189

External links

All links retrieved August 10, 2022.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.

↧ Download as ZWI file | Last modified: 02/04/2023 08:04:02 | 128 views

☰ Source: https://www.newworldencyclopedia.org/entry/Joseph_Heller | License: CC BY-SA 3.0

ZWI signed:

ZWI signed: KSF

KSF