Chaco Culture National Historical Park

From Nwe

From Nwe | Chaco Culture National Historical Park | |

|---|---|

| IUCN Category V (Protected Landscape/Seascape) | |

|

|

|

| Location: | San Juan County, New Mexico, USA |

| Nearest city: | Farmington, New Mexico |

| Area: | 33,974.29 acres (137.49 km²) |

| Established: | March 11, 1907 |

| Visitation: | 45,539 (in 2005) |

| Governing body: | National Park Service |

Chaco Culture National Historical Park is a United States National Historical Park and a UNESCO World Heritage Site hosting the densest and most exceptional concentration of pueblos in the American Southwest. The 34,000-acre park is located in northwestern New Mexico, in a relatively inaccessible valley cut by the Chaco Wash. Containing the most sweeping collection of ancient ruins north of Mexico, the park preserves one of America's most fascinating cultural and historic areas.

Between 900 and 1150 C.E., Chaco Canyon was a major center of culture for the Ancient Pueblo Peoples. Chacoans quarried sandstone blocks and hauled timber from great distances, assembling 15 major complexes which remained the largest buildings in North America until the nineteenth century. Many Chacoan buildings were aligned to capture the solar and lunar cycles, requiring generations of astronomical observations and centuries of skillfully coordinated construction.

The sites are considered sacred ancestral homelands of the Hopi, Navajo, and Pueblo peoples, who continue to maintain oral traditions recounting their historical migration from Chaco and their spiritual relationship to the land. While park preservation efforts often conflict with native religious beliefs, tribal representatives work closely with the National Park Service to share their knowledge and respect the heritage of the Chacoan culture.

While we most often appreciate National Parks for their present natural beauty, Chaco is appreciated most for its mysterious past.

Geography

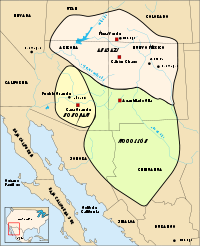

Chaco Canyon lies within the San Juan Basin, atop the vast Colorado Plateau, surrounded by the Chuska Mountains in the west, the San Juan Mountains to the north, and the San Pedro Mountains in the east. Ancient Chacoans relied upon their dense forests of oak, piñon, ponderosa pine, and juniper to obtain timber and other resources. The canyon itself, located within lowlands circumscribed by dune fields, ridges, and mountains, runs in a roughly northwest-to-southeast direction and is rimmed by flat massifs known as mesas. Large gaps between the southwestern cliff faces (side canyons known as rincons) were critical in funneling rain-bearing storms into the canyon, boosting local precipitation levels. The principal Chacoan complexes, such as Pueblo Bonito, Nuevo Alto, and Kin Kletso, have elevations of 6,200 to 6,440 feet (1,890 to 1,963 m).

The alluvial canyon floor, which slopes downward to the northeast at a gentle grade of 30 feet per mile (6 meters per kilometer), is bisected by the Chaco Wash, an arroyo that only infrequently carries water. Of the canyon's aquifers, the largest are located at a depth that precluded the ancient Chacoans from tapping their groundwater; only a few smaller, shallower sources supported small springs. Significant surface water is virtually non-existent except in the guise of storm runoff flowing intermittently through arroyos.

Flora and fauna

Chaco Canyon's flora is typical of that found in the high deserts of North America: sagebrush and several species of cactus are interspersed with dry scrub forests of piñon and juniper, the latter primarily on mesa tops. The canyon receives less precipitation than many other parts of New Mexico located at similar latitudes and elevations; consequently, it does not have the temperate coniferous forests that are plentiful in areas to the east. The prevailing sparseness of both plants and wildlife was echoed in ancient times, when overpopulation, expanding cultivation, overhunting, habitat destruction, and drought may have led the Chacoans to strip the canyon of wild plants and game. As such, even during wet periods, the canyon was only able to sustain around 2,000 people.

The canyon's most notable mammalian species include the coyote, mule deer, elk, and antelope. Important smaller carnivores include the bobcats, badgers, foxes, and two species of skunk. The park hosts abundant populations of rabbits, porcupines, rodents—including several prairie dog towns—and small colonies of bats, which are present during the summer.

The canyon is able to support relatively few bird species due to its short supply of water. Roadrunners, large hawks (such as Cooper's Hawks and American Kestrels), owls, vultures, and ravens are some of the larger birds that make their home there. Sizeable populations of smaller birds, including warblers, sparrows, and house finches are common. Three species of hummingbirds are present, including the tiny Rufous Hummingbird who competes with the more mild-tempered Black-chinned Hummingbirds for breeding habitat in shrubs or trees located near water. Western (prairie) Rattlesnakes are occasionally seen in the backcountry, though various lizards and skinks are far more abundant.

Climate

An arid region of high scrubland and desert steppe, the canyon and wider basin average 8 inches (20 cm) of rainfall annually; the park averages 9.1 inches (231.1 mm). Chaco Canyon lies on the leeward side of extensive mountain ranges to the south and west, resulting in a rainshadow effect that leads to the prevailing lack of moisture in the region. Four distinct seasons define the region, with rainfall most likely between July and September; May and June are the driest months. Orographic precipitation, resulting from moisture wrung out of storm systems ascending mountain ranges around Chaco Canyon, is responsible for most precipitation in both summer and winter; rainfall increases with higher elevation.

The Chaco Canyon area is also characterized by remarkable climatic extremes: recorded temperatures range between −38 °F (−39 °C) to 102 °F (39 °C), and temperature swings of up to 60 °F in a single day are not unknown. The region averages less than 150 days without frost per year, and the local climate can swing wildly from years of plentiful rainfall to extended droughts. The heavy influence of the El Niño-Southern Oscillation phenomenon on the canyon's weather contributes to the extreme climatic variability.

Geology

After the supercontinent of Pangaea split apart during the Cretaceous period, the region became part of a shifting transition zone between a shallow inland sea, the Western Interior Seaway, and a band of plains and low hills to the west. A sandy and swampy coastline repeatedly shifted east and west, alternately submerging and uncovering the canyon's portion of what is now the Colorado Plateau.

As the Chaco Wash flowed across the upper strata of what is now the 400-foot (122 m) Chacra Mesa, it cut into it, gouging out the broad canyon over the course of millions of years. The mesa itself comprises sandstone and shale formations dating from the late Cretaceous, which are of the Mesa Verde formation. The canyon's bottomlands were later further eroded, exposing Menefee Shale bedrock; this was subsequently buried under approximately 125 feet (38 m) of deposited sediment. The canyon and mesa lie within the "Chaco Core," distinct from the wider Chaco Plateau; it is a relatively flat region of grassland with infrequent and interspersed stands of trees. Especially because the Continental Divide is only 15.5 miles (25 km) west of the canyon, geological characteristics and different patterns of drainage differentiate these two regions both from each other and from the nearby Chaco Slope, the Gobernador Slope, and the Chuska Valley.

History

Ancestral Puebloans

Archaeologists identify the first people in the broader San Juan Basin as hunter-gatherers designated as the Archaic; they in turn descended from nomadic Clovis hunters who arrived in the Southwest around 10,000 B.C.E. By approximately 900 B.C.E., these people lived at sites such as Atlatl Cave. The Archaic people left very little evidence of their presence in Chaco Canyon itself. However, by approximately 490 C.E., their descendants, designated as Basketmakers, were continuously farming within the canyon, living in Shabik'eshchee Village and other pithouse settlements.

A small population of Basketmakers remained in the Chaco Canyon area and developed through several cultural stages until around 800, when they were building crescent-shaped stone complexes, each comprising four to five residential suites abutting subterranean kivas, large enclosed areas set aside for religious observances and ceremonies. These structures have been identified as characteristic of the Early Pueblo People. By 850, the Pueblo population, also known as the "Anasazi," had rapidly expanded, with members residing in larger, denser pueblos. There is strong evidence of a canyon-wide turquoise processing and trading industry dating from the tenth century. At this time, the first section of the massive Pueblo Bonito complex was built, beginning with a curved row of 50 rooms near its present north wall.

The cohesive system that characterized Chacoan society began disintegrating around 1140, perhaps in response to a severe 50-year drought that began in 1130; chronic climatic instability, including a series of severe droughts, again struck the region between 1250 and 1450. Other factors included water management patterns (leading to arroyo cutting) and deforestation. Outlying communities began to disappear and, by the end of the century, the buildings in the central canyon had been carefully sealed and abandoned. Archaeological and cultural evidence leads scientists to believe people from this region migrated south, east, and west into the valleys and drainages of the Little Colorado River, the Rio Puerco, and the Rio Grande.

Athabaskan succession

Numic-speaking peoples, such as the Ute and Shoshone, were present on the Colorado Plateau beginning in the twelfth century. Nomadic Southern Athabaskan speaking peoples, such as the Apache and Navajo, succeeded the Pueblo people in this region by the fifteenth century; in the process, they acquired Chacoan customs and agricultural skills. Ute tribal groups also frequented the region, primarily during hunting and raiding expeditions. The modern Navajo Nation lies west of Chaco Canyon, and many Navajo live in surrounding areas. The arrival of the Spanish in the seventeenth century inaugurated an era of subjugation and rebellion, with the Chaco Canyon area absorbing Puebloan and Navajo refugees fleeing Spanish rule. In succession, as first Mexico, then the U.S., gained sovereignty over the canyon, military campaigns were launched against the region's remaining inhabitants.

Excavation and protection

The trader Josiah Gregg was, in 1832, the first to write about the ruins of Chaco Canyon, referring to Pueblo Bonito as "built of fine-grit sandstone." In 1849, a U.S. Army detachment passed through and surveyed the ruins. The location was so remote, however, that over the next 50 years the canyon was scarcely visited. After a brief reconnaissance by Smithsonian scholars in the 1870s, formal archaeological work began in 1896, when a party from the American Museum of Natural History (the Hyde Exploring Expedition) began excavating in Pueblo Bonito. They spent five summers in the region, sent over 60,000 artifacts back to New York, and operated a series of trading posts.

In 1901 Richard Wetherill, who worked for the Hyde brothers and their expedition, claimed a homestead of 161 acres of land that included Pueblo Bonito, Pueblo del Arroyo, and Chetro Ketl. While investigating Wetherill's land claim, federal land agent Samuel J. Holsinger reported the physical setting of the canyon and the sites, noted prehistoric road segments and stairways above Chetro Ketl, and documented prehistoric dams and irrigation systems. His report (which went unpublished) strongly recommended the creation of a national park to encompass and preserve Chacoan sites. The next year, Edgar Lee Hewett, who was president of New Mexico Normal University, mapped many Chacoan sites. Hewett and others helped to enact the Federal Antiquities Act of 1906, which was the first U.S. law protecting antiquities; it was, in effect, a direct consequence of controversy surrounding Wetherill's activities in the Chaco Canyon area. The Act also allowed the President to establish national monuments. President Theodore Roosevelt thus proclaimed Chaco Canyon National Monument on March 11, 1907; Wetherill relinquished his claim on several parcels of land he held in Chaco Canyon.

In 1949, Chaco Canyon National Monument was expanded with lands deeded from the University of New Mexico. In return, the university maintained scientific research rights to the area. By 1959, the National Park Service had constructed a park visitor center, staff housing, and campgrounds. As a historic property of the National Park Service, the National Monument was listed on the National Register of Historic Places on October 15, 1966. In 1971, researchers Robert Lister and James Judge established the Chaco Center, a division for cultural research that functioned as a joint project between the University of New Mexico and the National Park Service. A number of multi-disciplinary research projects, archaeological surveys, and limited excavations began during this time. The Chaco Center extensively surveyed the Chacoan roads, well-constructed paths radiating from the central canyon. The results from such research conducted at Pueblo Alto and other sites dramatically altered accepted academic interpretations of both the Chacoan culture and the Four Corners region of the American Southwest.

The richness of the cultural remains at park sites led to the expansion of the small National Monument into the Chaco Culture National Historical Park on December 19, 1980, when an additional 13,000 acres (53 km²) were added to the protected area. In 1987, the park was designated a World Heritage Site by UNESCO. To safeguard Chacoan sites on adjacent Bureau of Land Management and Navajo Nation lands, the Park Service developed the multi-agency Chaco Culture Archaeological Protection Site program. These initiatives have detailed the presence of more than 2,400 archeological sites within the current park's boundaries; only a small percentage of these have been excavated.

Sites

The Chacoans built their complexes along a nine-mile (14 km) stretch of canyon floor, with the walls of some structures aligned cardinally and others aligned with the 18.6-year cycle of minimum and maximum moonrise and moonset.

Immense complexes known as "Great Houses" were key centers exemplifying Chacoan architectural and worship styles. Although forms evolved as the centuries passed, the houses maintained several core characteristics. Most notable is their sheer bulk; most complexes in Chaco Canyon averaged more than 200 rooms each, with some reaching up to 700 rooms. The sizes of individual rooms were also substantial, with high ceilings when compared to buildings erected in preceding Anasazi periods. They were also well-planned, with vast sections or wings erected in a single stage, rather than in increments.

Ceremonial structures known as kivas were built in proportion to the number of rooms in a pueblo. On average, one small kiva was built for every 29 rooms. Nine complexes also each hosted an oversized Great Kiva, which could range up to 63 feet (19 m) in diameter. All Chacoan kivas share distinctive architectural features, including T-shaped doorways and stone lintels.

Nine Great Houses are positioned along the north side of Chaco Wash, at the base of massive sandstone mesas. Other Great Houses are found on mesa tops or in nearby washes and drainage areas. There are 14 recognized Great Houses, which are grouped below according to geographic positioning with respect to the canyon.

Central canyon

The central portion of the canyon contains the largest Chacoan complexes.

- Pueblo Bonito ("Beautiful Village") - covering almost 2 acres (8,000 m²) and comprising at least 650 rooms, it is the largest Great House; in parts of the complex, the structure was four stories high. The builders' use of core-and-veneer architecture and multi-story construction necessitated massive masonry walls up to 3 feet (1 m) thick. Pueblo Bonito is divided into two sections by a wall precisely aligned to run north-south, bisecting the central plaza. A Great Kiva was placed on either side of the wall, creating a symmetrical pattern common to many Chacoan Great Houses. The complex, upon completion, was roughly the size of the Roman Colosseum.

- Pueblo del Arroyo - founded between 1050 and 1075 and completed in the early twelfth century, it is located near Pueblo Bonito at a drainage outlet known as South Gap. Casa Rinconada, hosting a Great Kiva and relatively isolated from other sites in Chaco Canyon, sits to the south side of Chaco Wash, adjacent to a Chacoan road leading to a set of steep stairs that reached the top of Chacra Mesa. The kiva stands alone, with no residential or support structures; it once had a 39-foot (12 m) passageway leading from the underground kiva to several above-ground levels.

- Chetro Ketl—located near Pueblo Bonito, bears the typical D-shape of many other central complexes, but is slightly smaller. Begun between 1020 and 1050, its 450–550 rooms shared just one Great Kiva. Scientists estimate that it took 29,135 person-hours of construction to erect Chetro Ketl alone; Hewett estimated that it required the wood of 5,000 trees and 50 million stone blocks.

- Kin Kletso ("Yellow House") - was a medium-sized complex located 0.5 miles (0.8 km) west of Pueblo Bonito; it shows strong evidence of construction and occupation by Pueblo peoples from the northern San Juan Basin. Its rectangular shape and design is related to the Pueblo II cultural group, rather than the Pueblo III style or its Chacoan variant. It contains around 55 rooms, four ground-floor kivas, and a two-story cylindrical tower that may have functioned as a kiva or religious center. Evidence of an obsidian production industry was discovered near the village, which was erected between 1125 and 1130.

- Pueblo Alto - a Great House of 89 rooms, is located on a mesa top near the middle of Chaco Canyon, and is 0.6 miles (1 km) from Pueblo Bonito; it was begun between 1020 and 1050 during a wider building boom throughout the canyon. Its location made the community visible to most of the inhabitants of the San Juan Basin; indeed, it was only 2.3 miles (3.7 km) north of Tsin Kletsin, on the opposite side of the canyon.

- The community was the center of a bead- and turquoise-processing industry that influenced the development of all villages in the canyon; chert tool production was also common. Research conducted by archaeologist Tom Windes at the site suggests that only a handful of families, perhaps as few as five to twenty, actually lived in the complex; this may imply that Pueblo Alto served a primarily non-residential role.

- Nuevo Alto - another Great House, was built on the north mesa near Pueblo Alto; it was founded in the late 1100s, a time when the Chacoan population was declining in the canyon.

Outliers

In Chaco Canyon's northern reaches lies another cluster of Great Houses.

- Casa Chiquita ("Small House") - a village built in the 1080s when, in a period of ample rainfall, Chacoan culture was expanding. Its layout featured a smaller, squarer profile; it also lacked the open plazas and separate kivas of its predecessors. Larger, squarer blocks of stone were used in the masonry; kivas were designed in the northern Mesa Verdean tradition.

- Peñasco Blanco ("White Bluff") - two miles down the canyon is an arc-shaped compound built atop the canyon's southern rim in five distinct stages between AD 900 and 1125. A cliff painting (the "Supernova Platograph") nearby seems to record the sighting of the SN 1054 supernova on July 5, 1054.

- Hungo Pavi - located just 1 mile (2 km) from Una Vida, measured 872 feet (266 m) in circumference. Initial explorations revealed 72 ground-level rooms, with structures reaching four stories in height; one large circular kiva has been identified.

- Kin Nahasbas - another major ruin, built in either the ninth or tenth century; it is located slightly north of Una Vida, positioned at the foot of the north mesa. Limited excavation has been conducted in this area.

- Tsin Kletzin ("Charcoal Place") - a compound located on the Chacra Mesa and positioned above Casa Rinconada, is 2.3 miles (3.7 km) due south of Pueblo Alto, on the opposite side of the canyon. It lies near Weritos Dam, a massive earthen structure that scientists believe provided Tsin Kletzin with all of its domestic water. The dam worked by retaining stormwater runoff in a reservoir. However, massive amounts of silt accumulated during flash floods would have forced the residents to regularly rebuild the dam and dredge the catchment area.

- Una Vida ("One Life") - deeper into the canyon is one of the three earliest Great Houses with construction beginning around 900 C.E. Comprising at least two stories and 124 rooms, it shares an arc or D-shaped design with its contemporaries, Peñasco Blanco and Pueblo Bonito, but has a unique "dog leg" addition made necessary by topography. It is located in one of the canyon's major side drainages, near Gallo Wash, and was massively expanded after 930.

- Wijiji ("Greasewood") - comprising just over 100 rooms, is the smallest of the Great Houses. Built between 1110 and 1115, it was the last Chacoan Great House to be constructed. Somewhat isolated within the narrow wash, it is positioned 1 mile (2 km) from neighboring Una Vida.

Directly north are communities that are even more remote, including Salmon Ruins and Aztec Ruins, which are located along the San Juan and Animas Rivers near Farmington; these were built during a 30-year wet period that began in 1100. Located 60 miles (100 km) directly south of Chaco Canyon, on the Great South Road, lies another cluster of outlying communities. The largest of these is Kin Nizhoni, which stands atop a 7,000-foot (2,100 m) mesa surrounded by marsh-like bottomlands.

Activities

The park also provides other activities in addition to exploration of the ruins.

Hiking

- The Pueblo Alto Trail is a popular 5.4-mile (8.7-km) loop trail that leads to the Pueblo Alto and New Alto, with its twenty-eight rooms and one kiva. This trail also allows outstanding overlooks of Pueblo Bonito, which had five stories and up to six hundred rooms.

- The Penasco Blanco Trail is 6.4 miles (10.3 km) and leads to Pueblo Bonito, one of the earliest pueblos in the canyon. Petroglyphs can be seen on the canyon wall.

- The Wijiji Trail is 3.0 miles (4.8 km) leads to the Wijiji pueblo built with exceptional symmetry around AD 1100.

- The South Mesa Trail is 3.0 miles (4.8 km) and leads the hiker 100 feet higher than any other point along the canyon trails. There is an abundant array of wildflowers seen here in the spring and summer.

Biking

- Wijiji Trail is 3.0 miles (4.8 km) and follows the old Sargent Ranch road up the north side of Chaco Wash.

- Kin Klizhin is 23.8 miles (38 km) and follows U.S. Highway 57 south along Navajo Tribal land.

Camping

- Gallo Campground is located just one mile east of the Visitor Center and open year-round.

Stargazing

Open from April to October, the Chaco Night Sky Program presents astronomy programs and telescope viewing of the spectacular dark night sky.

Sources and Further reading

- Diamond, Jared. 2005. Collapse: how societies choose to fail or succeed. London: Allen Lane. ISBN 0713992867

- Fagan, Brian M. 2005. Chaco Canyon: archeologists explore the lives of an ancient society. Oxford: University Press. ISBN 0195170431

- Fagan, Brian M. 1998. From black land to fifth sun: the science of sacred sites. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley. ISBN 0201959917

- Frazier, Kendrick. 1986. People of Chaco: a canyon and its culture. New York: Norton. ISBN 0393304965

- Hayes, Alden C., David M. Brugge, and W. James Judge. 1988. Archeological surveys of Chaco Canyon, New Mexico. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press. ISBN 082631029X

- Hopkins, Ralph Lee. 2002. Hiking the Southwest's geology: Four Corners Region. Seattle: Mountaineers Books. ISBN 0898868564

- Kelley, David H., and E. F. Milone. 2005. Exploring ancient skies: an encyclopedic survey of archaeoastronomy. New York: Springer. ISBN 0387953108

- National Park Service. 2005.

United States World Heritage Periodic Report: Chaco Culture National Historical Park (Section II). Retrieved June 23, 2007.

- National Park Service. 2007. Chaco Culture. Retrieved June 23, 2007.

- Noble, David Grant. 1984. New light on Chaco Canyon. Santa Fe, NM: School of American Research Press. ISBN 0933452101

- Noble, David Grant. 1991. Ancient ruins of the Southwest: an archaeological guide. Flagstaff, Ariz: Northland Pub. ISBN 0873585305 and ISBN 9780873585309

- Plog, Stephen. 1997. Ancient peoples of the American Southwest. New York: Thames and Hudson. ISBN 050027939X

- Reynolds, A., J. Betancourt, and J. Quade. 2005. Sourcing of ponderosa pine used in Anasazi Great House construction at Chaco Canyon, New Mexico. Journal of Archaeological Science. Retrieved June 23, 2007.

- Sofaer, A. 1997. The Primary Architecture of the Chacoan Culture: A Cosmological Expression. Solstice Project. Retrieved June 23, 2007.

- Sofaer, and Ritterbush. 2001. VISUAL ANTHROPOLOGY - The Mystery of Chaco Canyon (video). American Anthropologist 103 (3): 818.

- Strutin, Michal, and George H. H. Huey. 1994. Chaco: a cultural legacy. Tucson: Southwest Parks & Monuments Association. ISBN 1877856452

- Stuart, David E., and Susan B. Moczygemba-McKinsey. 2000. Anasazi America. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press. ISBN 082632178X

External links

All links retrieved January 25, 2017.

- National Park Service. Chaco Culture National Historical Park.

- Desert USA. Chaco Culture National Historical Park.

- World Heritage. Chaco Culture.

| National Historical Parks of the United States | |

|---|---|

| Adams • Appomattox Court House • Boston • Cane River Creole • Cedar Creek and Belle Grove • Chaco Culture • Chesapeake and Ohio Canal • Colonial • Cumberland Gap • Dayton Aviation Heritage • George Rogers Clark • Harpers Ferry • Hopewell Culture • Independence • Jean Lafitte • Kalaupapa • Kaloko-Honokohau • Keweenaw • Klondike Gold Rush • Lewis and Clark • Lowell • Lyndon B. Johnson • Marsh-Billings-Rockefeller • Minute Man • Morristown • Natchez • New Bedford Whaling • New Orleans Jazz • Nez Perce • Pecos • Pu'uhonua o Honaunau • Rosie the Riveter/World War II Home Front • Salt River Bay • San Antonio Missions • San Francisco Maritime • San Juan Island • Saratoga • Sitka • Tumacácori • Valley Forge • War in the Pacific • Women's Rights |

Cahokia | Carlsbad Caverns | Chaco Culture | Everglades | Grand Canyon | Great Smoky Mountains | Hawaii Volcanoes | Independence Hall | Kluane / Wrangell-St. Elias / Glacier Bay / Tatshenshini-Alsek (w/ Canada) | La Fortaleza and San Juan National Historic Site, Puerto Rico | Mammoth Cave | Mesa Verde | Monticello and University of Virginia | Olympic | Pueblo de Taos | Redwood | Statue of Liberty | Waterton Glacier International Peace Park (w/ Canada) | Yellowstone | Yosemite

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.

↧ Download as ZWI file | Last modified: 02/04/2023 04:55:01 | 44 views

☰ Source: https://www.newworldencyclopedia.org/entry/Chaco_Culture_National_Historical_Park | License: CC BY-SA 3.0

ZWI signed:

ZWI signed:

KSF

KSF