Ottoman Empire

From Conservapedia

From Conservapedia The Ottoman Empire was a multinational Sunni Muslim state which ruled much of the Middle East as well as parts of North Africa and the Balkans in Europe from 1299 until 1922. Its government, based in Istanbul, was called "The Porte" or "The Sublime Porte". It was the predecessor of present-day Turkey.

Contents

Growth[edit]

For several hundred years Turkish tribes from central Asia had been moving into Anatolia (modern day Turkey). The first major Ottoman leader was Osman (1259-1326); Europeans pronounced his name as "Ottoman", and the name stuck. Osman extended his realm by conquering Byzantine holdings province by province.

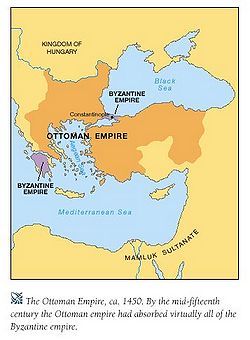

Osman's successors moved into Europe and squeezed the Byzantine Empire into a smaller and smaller fragment, a process that took a century. Murad I (reigned 1361-1389), a remarkable Sultan who ensured the permanence of Ottoman forces in Europe by the incorporation of the conquered city of Adrianople into his realm in 1361. Murad won a great victory over the Christian Serbs and Bosnians at Kosovo in 1389, but he was killed. Bayazid I became sultan and, as was usually done, killed his brothers to solidify his power. He extended Ottoman rule throughout most of Anatolia. However, he was defeated in 1402 by Mongol invaders and his empire shrank and after his death in 1403 his three sons fought each other for control. There were repeated wars in the Balkans. In 1451 Mehmed II (archaic Mohammed II, reigned 1451 to 1481) came to power, and built for the first time a strong Ottoman state, with an effective bureaucracy and army. He ended local dynasties and repulsed the Christians from Hungary and Venice.

Adrianople, now called Edirne, served as the European capital of the Ottoman state. In 1453 Mehmed II finally captured the depopulated, poverty-stricken Byzantine capital of Constantinople, renamed it Kostantiniyye (officially Istanbul since 1930), and made it into a glorious imperial capital, complete with scholars and historians to sing his praises.

Tolerance[edit]

When the empire was growing it adopted a policy toward Christians and Jews, and toward various ethnic groups. They would all be tolerated and have a degree of self-government, provided they acknowledged the empire and non-Muslims paid a tax. This was the "millet" system and created a segregated second-class status for minorities. Because of the increased activities of Protestant missionaries, a Protestant millet was set up in 1850, which allowed for the creation of schools and colleges aimed at non-Muslims.

Janissaries[edit]

A special military cadre of Janissaries was created as an imperial force totally loyal to the Empire. They were a highly trained, disciplined, military force founded in the 1360s as a select bodyguard drawn from the fittest Christian prisoners, youthful soldiers, and slaves from throughout the Ottoman Empire. By 1600 all new recruits were Muslim volunteers.

Threat to Europe[edit]

Suleiman the Magnificent reigned 1520–1566 and expanded into Europe, capturing Belgrade and Buda (Budapest) and threatening—but failing—to capture Vienna. His reign marked the high point of Ottoman prowess.The Ottoman Empire continued to militarily force their way into south eastern Europe. Its failure in the The Great Siege of Malta (1565) and defeat at the Battle of Lepanto (1572) were the turning points in its expansion in the Mediterranean. During this period, a strengthening Muscovy (Russia) was winning Muslim territory and pushing at Ottoman borders. As Europe continued to make heavy military strides in the following centuries, the Ottoman Empire began to lag and lose status as a major power. Wars with Russia became frequent in the later part of its existence, with the Russians often getting the better of the engagements.

Wars with Russia[edit]

The peace treaty of Constantinople (1700) confirmed the victory of Russia in the Russo-Turkish war of 1686-1700. As a result, Russia annexed an important section of the steppe north of the Black Sea (including the fortresses and ports of Azov and Taganrog). However, even though a Russian naval fleet was present in the Sea of Azov, the strategic Kerch Strait remained under Ottoman control, blocking Russian access to the Black Sea, which remained an Ottoman domain. Under the circumstances, the entire period of Russian-Ottoman peace between 1700 and 1710 was tense. Turning to good advantage the involvement of Russia in the Northern War of 1700-21, the Porte launched and won the Russian-Ottoman war of 1710-11. Defeated, Russia was obliged to restore to the Porte the territories annexed in 1700. Russia finally gained its much-coveted access to the Black Sea only in 1774, by the Russian-Ottoman peace treaty of Kuchuk Kainarji.

"Sick Man of Europe"[edit]

After 1800 the steady decline of the Empire was in sharp contrast to the growth in wealth and military power in western Europe. The Empire was called "the sick man of Europe" and steadily lost influence and territory. In the 19th century the Empire was actually aided in its survival by Britain and France, who feared its collapse or loss of large amounts of land to Russia would destabilize the balance of power.

For many years the prevailing interpretation of the decline and collapse of the empire focused on internal failures. The Ottoman Empire originally had benefited from a series of energetic sultans to reach an apogee by 1600, but subsequent leadership failed and a combination of decadent sultans, manipulative harem women, and corrupt bureaucrats and military officials set in motion a long and steady decline that dragged on over the next 320 years until the final collapse in the aftermath of World War I. Efforts to get rid of old power centers (such as the Janissaries) and instead adopt modern European methods and technology bought a little time, but could not prevent the seizure of Egypt by the British. The rise of ethnic or language-based nationalism after 1800 meant that one group after another wanted out, starting with the Slavs and the Greeks. Finally, the Arabs and the Turks themselves wanted out, and after the poor performance in the World War, no one wanted to stay in. Instead of its historic tolerance, the Empire became a killing machine, most notoriously with the massacres of the Bulgarians in the 1870s and the genocide of the Armenians 1890-1915.

More recently many historians have emphasized the tolerance and flexibility of the Empire as explanations of why it lasted so long. They acknowledge the weaknesses but blame the final collapse on external factors.

Destruction of the Janissaries[edit]

By 1800, the Janissaries, over 100,000 strong, had become politically powerful but were ill-disciplined and badly outmatched by European armies. Many had become local businessmen and had lost their military skills. In 1807 Sultan Selim III angered the Janissaries by attempting to modernize the army along European lines; they revolted and overthrew him and were now a negative force. The solution was to dissolve the units and kill the leaders, which was done by a massacre organized by the sultan in 1826 and performed by artillery units loyal to the sultan.

Holy Places[edit]

In 1852 the Christian holy places in Jerusalem were subjected to a regulatory status known as the "status quo" by Ottoman authorities. The imposition of the status quo regulations was an attempt to put an end to ongoing strife between Greek Orthodox and Roman Catholic factions engaged in a nasty dispute over control of the holy places. The status quo reaffirmed the precedence of the Greek Orthodox Church. The 1878 Treaty of Berlin confirmed the decision of the Ottoman rulers of Jerusalem, and this arrangement was passed on to the successive British and Israeli governors of Jerusalem.

In 1860 fighting between Christians and Druze in central Mount Lebanon led to intervention by the European powers to establish the Beirut Committee, under the chairmanship of Ottoman foreign minister Fuad Pasha and comprised of representatives from Britain, France, Russia, Austria, and Prussia, to resolve the conflict. Britain identified the weaknesses of the administration of the Porte in Lebanon to be corruption, strategic isolation, and lack of communication between the Ottoman bureaucracy and the local Arab population, but no serious reforms were undertaken.

Bulgarian massacres[edit]

The "Bulgarian Horrors" were systematic massacres of thousands of Bulgarian Christians by Ottoman forces in 1876-77. In Britain Liberal leader William Ewart Gladstone exploited the horror to embarrass the Conservative government of Benjamin Disraeli, who tried to prop up the Ottoman regime as a counter-weight to Russia. Meanwhile, in 1882 the British seized effective control over Egypt and the Suez Canal; Egypt nominally still belonged to the Ottoman Empire but the reality was that the Empire was crumbling.

Armenians[edit]

- See also: Armenian genocide

In the 1870s from the point of view of both the Ottoman administrators and the Muslim population, the Christian Armenians were considered 'tebaa-i sadika' (loyal subjects), loyal to the state and on good terms with their Muslim neighbors. Nevertheless, the rise of nationalist ideologies in Europe and, in particular, the success of the Greek and Serbian independence movements made a deep impression on Armenian intellectuals. With the support of Britain, this impression quickly turned into a widespread and organized revolt against the Ottoman state and evolved into a movement for independence. After the 1877-78 Russo-Turkish War, Britain, which supported this revolt, began a campaign against the Ottomans based on several arguments: the Ottoman state and Turks, in general, were not civilized, the citizens of the empire were not allowed basic freedoms, and the government subjected its citizens to immense cruelty and massacres. Full-scale genocide against the Armenians came during World War I when 600,000 were deliberately killed.

Arabia[edit]

The decline of Ottoman influence in Arabia, 1750-1914, was paralleled by the rise of the Saudi state, which was helped by the British and the Russians, who wanted to increase their colonial influence in the Muslim world by undermining the influence of the Ottoman Empire as the leader of Islam.

20th century[edit]

- See also: Turkey

The Committee of Union and Progress (CUP), known collectively as the Young Turks, came to power in 1908.

World War I[edit]

The Ottoman Empire joined Germany and Austria (the Central Powers) during World War I (1914-1918) and collapsed after their defeat. The Young Turks who controlled the government, anxious to have an all-Muslim empire, saw the chance to get rid of the Christian Armenians. Evacuations and killings during the Armenian genocide of 1915 left 600,000 dead and eliminated all the Armenians inside Turkey.The British expected easy victories, and sent armies into Mesopotamia (Iraq), which were badly defeated, and landed at Gallipoli in order to capture Istanbul, but failed badly in 1915. However, the British were successful in moving from Egypt to conquer Palestine, using the aid of Arab nationalists stirred up by British officer Lawrence of Arabia (T.E. Lawrence).

Winston Churchill and other top British leaders envisioned an operation in which they placed their strength against Ottoman weakness. Instead of engaging a feeble opponent, however, the British faced the best-trained and best-led divisions in the Ottoman army and were up against the most heavily fortified and well-prepared positions in the Ottoman Empire. In command and control the Ottoman army performed well at all levels, and Ottoman soldiers proved to be effective fighters on the defensive. The Germans, furthermore, provided very talented generals and senior staff members to aid and help direct the Ottoman effort. As a result, the Ottoman army fought the British to a stalemate, leading the British to abandon the campaign.[1]

The secret wartime Sykes-Picot Agreement in 1916 was a plan for Russian, British, and French administration of dismembered Ottoman lands in the Middle East and Central Asia. Russia dropped out but at the 1919 Paris Peace Conference much of the territory of the Ottoman Empire was placed under British and French control, while Mustafa Kemal Atatürk led a revolution and established the secular nation of Turkey.

Bibliography[edit]

- Barkey, Karen. Empire of Difference: The Ottomans in Comparative Perspective. (2008) 357pp excerpt and text search

- Braude, Benjamin, and Bernard Lewis, eds. Christians and Jews in the Ottoman Empire: The Functioning of a Plural Society (1982) online edition

- Clot, André. Suleiman the Magnificent. 1993. 399 pp

- Finkel, Caroline. Osman's Dream: The History of the Ottoman Empire (2006), standard scholarly survey excerpt and text search

- Goffman, Daniel. The Ottoman Empire and Early Modern Europe (2002) online edition

- Goodwin, Jason. Lords of the Horizons: A History of the Ottoman Empire (2003) excerpt and text search

- Heywood, Colin. Writing Ottoman History: Documents and Interpretations. Ashgate, 2002. 376 pp.

- Holt, P. M. Egypt and the Fertile Crescent, 1516–1922: A Political History. 1966.

- Imber, Colin. The Ottoman Empire, 1300-1650: The Structure of Power (2003)

- Inalcik, Halil and Quataert, Donald, ed. An Economic and Social History of the Ottoman Empire, 1300-1914. 1995. 1026 pp.

- Itzkowitz, Norman. Ottoman Empire and Islamic Tradition. 1972.

- Kinross, Lord. Ottoman Centuries (1979)

- Kunt, Metin and Woodhead, Christine, ed. Süleyman the Magnificent and His Age: The Ottoman Empire in the Early Modern World. 1995. 218 pp.

- Levy, Avigdor, ed. Jews, Turks, Ottomans: A Shared History, Fifteenth to the Twentieth Century. (2002). 304 pp.

- McCarthy, Justin. The Ottoman Turks: An Introductory History to 1923 1997 online edition

- Murphy, Rhoads Ottoman Warfare 1500-1700 (1999) 278 pp.

- Ochsenwald, William, and Sydney Nettleton Fisher. The Middle East: A History (2003) excerpt and text search

- Pamuk, Sevket. A Monetary History of the Ottoman Empire. 1999. 276 pp.

- Parry, V.J. A History of the Ottoman Empire to 1730 (1976)

- Pierce, Leslie P. The Imperial Harem: Women and Sovereignty in the Ottoman Empire. 1993. 374 pp.

- Quataert, Donald. The Ottoman Empire, 1700-1922 (2005), standard scholarly survey excerpt and text search

- Shaw, Stanford J., and Ezel Kural Shaw. History of the Ottoman Empire and Modern Turkey. Vol. 1, 1977.

- Somel, Selcuk Aksin. Historical Dictionary of the Ottoman Empire. (2003). 399 pp.

- Turnbull, Stephen. The Ottoman Empire 1326-1699 (2003) 95 pp online edition

- Wheatcroft, Andrew. The Ottomans. 384 pp.

Post 1830[edit]

- Ahmad, Feroz. The Young Turks: The Committee of Union and Progress in Turkish Politics, 1908–1914, (1969).

- Arnold, Guy. Historical Dictionary of the Crimean War. (2002). 179 pp.

- Black, Cyril E., and L. Carl Brown. Modernization in the Middle East: The Ottoman Empire and Its Afro-Asian Successors. 1992.

- Erickson, Edward J. Ordered to Die: A History of the Ottoman Army in the First World War (2000) excerpt and text search

- Faroqhi, Suraiya. Subjects of the Sultan: Culture and Daily Life in the Ottoman Empire. (2000) 358 pp.

- Findley, Carter. Bureaucratic Reform in the Ottoman Empire. 1980.

- Fortna, Benjamin C. Imperial Classroom: Islam, the State, and Education in the Late Ottoman Empire. (2002) 280 pp.

- Fromkin, David. A Peace to End All Peace: The Fall of the Ottoman Empire and the Creation of the Modern Middle East (2001) excerpt and text search

- Göçek, Fatma Müge. Rise of the Bourgeoisie, Demise of Empire: Ottoman Westernization and Social Change. (1996). 220 pp.

- Hale, William. Turkish Foreign Policy, 1774-2000. (2000). 375 pp.

- Inalcik, Halil and Quataert, Donald, ed. An Economic and Social History of the Ottoman Empire, 1300-1914. 1995. 1026 pp.

- Karpat, Kemal. Ottoman Population, 1830–1914 1985.

- Karpat, Kemal H. The Politicization of Islam: Reconstructing Identity, State, Faith, and Community in the Late Ottoman State. (2001). 533 pp.

- Kayali, Hasan. Arabs and Young Turks: Ottomanism, Arabism, and Islamism in the Ottoman Empire, 1908-1918 (1997); complete text online

- Kushner, David. The Rise of Turkish Nationalism, 1876–1908. 1977.

- Miller, William. The Ottoman Empire, 1801–1913. (1913) full text online

- Owen, Roger. The Middle East in the World Economy, 1800–1914. (1981)

- Quataert, Donald. Social Disintegration and Popular Resistance in the Ottoman Empire, 1881–1908. 1983.

- Shaw, Stanford J., and Ezel Kural Shaw. History of the Ottoman Empire and Modern Turkey. Vol. 2, Reform, Revolution, and Republic: The Rise of Modern Turkey, 1808–1975. (1977). excerpt and text search

- Toledano, Ehud R. The Ottoman Slave Trade and Its Suppression, 1840–1890. (1982)

Notes[edit]

- ↑ Edward J. Erickson, "Strength Against Weakness: Ottoman Military Effectiveness At Gallipoli, 1915." Journal Of Military History 2001 65(4): 981-1011

Categories: [Former Countries] [Middle East] [Balkans] [World War I] [Medieval History] [European History] [Ottoman Empire] [Turkey]

↧ Download as ZWI file | Last modified: 02/18/2023 09:40:12 | 209 views

☰ Source: https://www.conservapedia.com/Ottoman_Empire | License: CC BY-SA 3.0

ZWI signed:

ZWI signed:

KSF

KSF