Beni-Israel

From Jewish Encyclopedia (1906)

From Jewish Encyclopedia (1906) Beni-Israel:

By: Joseph Jacobs , Joseph Ezekiel

Native Jews of India, dwelling mainly in the presidency of Bombay and known formerly by the name of Shanvar Telis ("Saturday Oil-Pressers") in allusion to their chief occupation and their Sabbath-day. The Beni-Israel avoided the use of the name "Jew," probably in deference to the prejudice of their Mohammedan neighbors, and preferred the name Beni-Israel in reference to the favorable use of the term in the Koran (sura ii. 110). According to their own traditions, they are descended from the survivors of a band of Jews fleeing from persecution who were wrecked near the Henery and Kenery islands in the Indian ocean, fifteen miles from Cheul, formerly the chief emporium of the trade between Arabia and India. Seven men and seven women are stated to have been saved from drowning; and from them are descended the Beni-Israel. This is said to have been from sixteen hundred to eighteen hundred years ago. Benjamin of Tudela appears to have heard of them in the twelfth century, and Marco Polo in the thirteenth; but they were first brought to the knowledge of Europeans, simultaneously with the White and Black Jews of Cochin on the Malabar coast, by Christian missionaries in India, like Drs. C. Buchanan and Wilson,at the beginning of the nineteenth century. On the advent of the Sassoon family at Bombay, more direct interest was taken in the Beni-Israel by Western Jews, and much educational work has since been done among them.

Internal History.The Beni-Israel themselves refer to two religious revivals among them during their stay in India: the first, placed by them about 900 years ago, due to David Rahabi , and another, about the year 1796, due to Samuel Divekar . According to tradition, Rahabi was a Cochin Jew, whose family had come from Egypt, and on visiting the Beni-Israel he found among them several customs similar to those current among Jews, and to test them he gave their women some fish to cook, including some that had neither fins nor scales. These they separated from the others, saying that they never ate them. Rahabi was thereupon satisfied they were really Jews, and imparted instruction to them. After the attention of the European Jews had been called to the Beni-Israel, the rites and ceremonies of the latter were assimilated to those of the Sephardic Jews, and prayer-books in Mahrati, their vernacular, have been provided for them. Previously, however, to this their festivals and customs differed considerably from the rest of the Jews both in name and in ceremonial.

The festivals of the Beni-Israel, before they became acquainted with the ordinary religious calendar of modern Jews, had only native names, one set of which was in Mahrati and the other in Hindustani. The latter are attributed to the reforms of David Rahabi. Many of the names in the former end in "San," meaning "holiday," and among them are the following:

- Navyacha San ("New-Year holiday"), kept on the first day of Tishri, the second-day observance not being known among the Beni-Israel.

- Khiricha San ("Pudding holiday"), on the evening of the fourth of Tishri. This was celebrated by eating "khir," a sort of pudding made of new corn mixed with coconut-juice and sweets; a censer with burning frankincense being placed near the dish. The khir was eaten by the family after saying the Shema`.

- Darfalnicha San ("Closing-of-doors holiday"), on the tenth of Tishri, during which they fasted from five o'clock in the evening until the next evening at seven. During it they did not stir out-of-doors, nor touch nor speak to people of other denominations. They dressed themselves in white, and believed that departed souls visited their habitations on the preceding day and left them on the following day, called Shila San ("Stale holiday"), on which day they gave alms to the poor and visited their friends.

- Holicha San, on the thirteenth and fourteenth of Adar; the former kept as a fast, and the latter as a feast, on which they sent home-made sweetmeats to one another. This corresponds to Purim; but the Beni-Israel did not observe the second day or "Shushan Purim."

- Anasi Dakacha San ("Anas-closing holiday"), on the fourteenth and twenty-first-of Nisan. This was celebrated by closing an earthen chatty or pot containing a sour liquid commonly used as sauce. This festival corresponded to Passover; but, as the Hindus generally did not use any leaven with their rice, the object of the ceremony seems to have been forgotten.

- Birdiacha San ("Birda-curry holiday"), on the ninth of Ab, on which they ate nothing but rice with a curry of "birda" or pulse. This was served on plantain-leaves. During the preceding eight days no meat was eaten. This corresponds to Tish'a be-Ab, in memory of the destruction of the Temple; but there does not seem to have been any conscious recognition of that fact.

The other festivals, chiefly known by the name of "Roja" (fasting), appear to have been of later introduction, and are connected with the reforms of David Rahabi. These are as follows:

- Ramzan, a fast held throughout the month of Elul; the name is doubtless derived from the Mohammedan month of fasting, "Ramazan."

- Navyacha Roja ("New-Year fast"), on the third of Tishri, corresponding to the fast of Gedaliah, but not associated with his murder.

- Elijah Hannabicha Oorus ("The fair of Elijah the Prophet"), to celebrate the ascension of Elijah on that day at Khandalla in the Konkan. Various kinds of fruit were placed on plates, together with "malida" (pieces of ricebread besmeared with sirup), and a censer of burning frankincense. The fruit was eaten by the family.

- Sababi Roja, a fast on the seventeenth of Tammuz, a reminiscence of the siege of Jerusalem, but not known as such by the Beni-Israel.

From this enumeration of the festivals it will appear that the Beni-Israel retain from the earliest times (as indicated by their Mahrati names ending with "San") the New-Year, Day of Atonement, Purim, Passover, Ninth of Ab, and in addition a form of Tabernacles which has been transferred to the Fourth of Tishri. Later on they introduced, doubtless under the influence of David Rahabi (asis shown by the Hindustani names), the fasts of Gedaliah, Ṭebet, and Tammuz, together with the New-Year of the trees, associated with the name of Elijah the Prophet; while still later the custom of fasting throughout the whole month of Elul seems to have been borrowed from the Mohammedans. The feasts of Pentecost and Ḥanukkah seem to have dropped out of use. It would appear that before the second revival under Samuel Divekar the only other remains of Judaism current among the Beni-Israel were the strict observance of the Sabbath, circumcision, and the reading of the Shema', which is the sole piece of Hebrew retained by them. The latter was said at every meal, at wedding-festivals, at burial-feasts, and indeed on all sacred occasions. The only animals considered fit for food were fowl, sheep, and goats. The Beni-Israel probably refrained from beef, in order not to offend their Hindu neighbors.

It is difficult at this time to determine with any degree of accuracy the relative age of the customs they follow. Even before the religious revival of 1796 the Beni-Israel customarily removed the sciatic nerve from animals used for food, and they salted the meat in order to abstract the blood from it; otherwise they did not observe the law of sheḥiṭah and bediḳah. They also left a morsel of bread or rice in a little dish after they had dined. Among them the birth of a girl was celebrated on the sixth night, and that of a boy on the sixth and eighth; and on the latter day the rite of circumcision was performed. Girls were usually betrothed some months before marriage; and until the wedding they wore the hair flowing from their shoulders. At the betrothal ceremony the intended bride and bridegroom sat face to face and dined together, sweetened rice being served to the assembly. On the day when the marriage ceremony was to take place the bridegroom, who had been crowned with a wreath of flowers, was led in procession on horse-back to the bride's house, and the ceremonytook place under a booth. At the feast held before the wedding took place a dish containing a piece of leaven cake, the liver of a goat, fried eggs, and a twig of "subja" was placed with burning frankincense on white cloth, and after the Shema' had been repeated the dish was taken inside and, with the exception of five pieces of the cakes and liver, which were set aside for the person officiating as priest, the food was eaten. Polygamy is allowed, and in some cases divorce is given according to the civil law; but the Beni-Israel did not practise "get," "yibbum," or "ḥaliẓah." An adulteress and her issue are regarded as "Black Israel."

After burials the mourners wash both themselves and their clothes, and on the third day the house is cleansed; the ceremony being known as "Tizova," or the "Third-Day Cleansing." When a person died, all the water was emptied from the pots in the house, and the body was buried with the head toward the east. Grape-juice or milk was drunk by those visiting the mourners in the evening during the days of mourning. It was customary for relatives and friends to bring "meals of condolence" to the house of mourning. On the seventh day after burial there was a mourning ceremony known as the "Jaharuth," in which a dish, containing cakes and pieces of liver, and a glass of liquor, was placed on a white sheet. After repeating the Shema' about a dozen times, the contents of the glass were drunk in honor of the dead; and after the food was eaten, the chief mourner was presented with a new turban by a relative. Jaharuth was also observed on the first, sixth, and twelfth months. If a boy were born after a vow made by the mother, his hair was not shaved for six or seven years, after which period it was completely shaved and weighed against coins (gold or silver), to be given in charity. The shaved hair was thrown into the sea and not burned. A feast was held in the evening, at which the mother was informed that she was free from her vow.

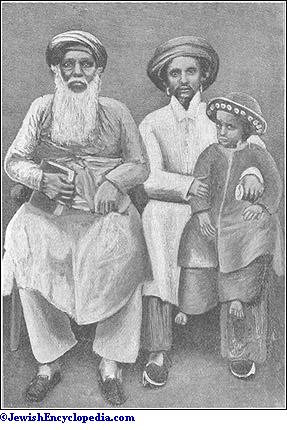

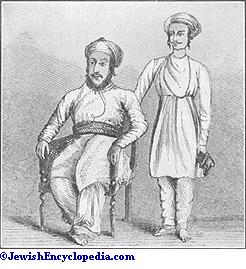

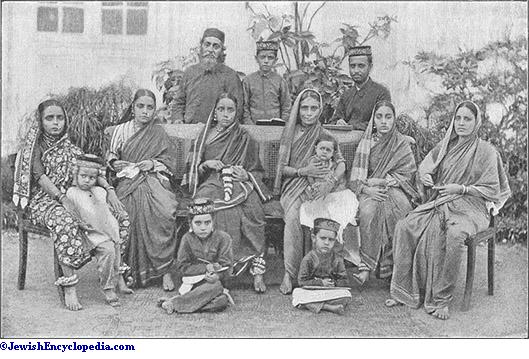

Costume and Names.Formerly the Beni-Israel wore turbans, but now they use mainly the Turkish fez. The women adopt the Hindu dress, and are accustomed to wear anklets and nose-rings. Most of the Beni-Israel names have been changed from Hebrew to Hindu forms; thus, "Ezekiel" into "Hassaji"; "Benjamin" into "Bunnajee"; "Abraham" into "Abajee"; "Samuel" into "Samajee"; "Elijah" into "Ellojee"; "Isaac" into "Essajee"; "Joseph" into "Essoobjee"; "Moses" into "Moosajee"; "Rahamim" into "Ramajee"; "David" into "Dawoodjee," and "Jacob" into "Akhoobjee." Their surnames are mostly derived from neighboring villages; thus, those who resided at Kehim were called "Kehimker," and those who lived at Pen were named "Penker."

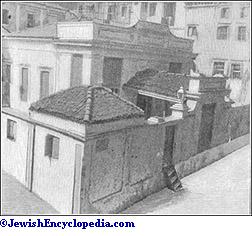

Later History.About 1795 Samuel Ezekiel Divekar , a Beni-Israel soldier in the East India Company's service, was captured by Tipu Sahib. He made a vow that if he escaped he would build a synagogue at Bombay. He succeeded in escaping, and built the synagogue Magen David, now called Sha'ar Ha-Raḥamim, at Bombay, and introduced the Sephardic ritual from Cochin. The Beni-Israel shortly afterward attracted the attention of Christian missionaries at Bombay, who about 1812 brought Michael Sargon from Cochin, who, though a convert to Christianity, opened schools for the Beni-Israel in Bombay, Rebdanda, and Palle for over thirty years; explaining to the children parts of the Old Testament, and rarely, if ever, speaking of Christianity to them.

The chief instrument in introducing the full knowledge of Judaism to the Beni-Israel was Shellomo (Solomon) Shurrabi , who was wrecked near Bombay about 1836, and for twenty years acted as religious instructor of the community. Owing to his influence several new synagogues were builtin the vicinity of Bombay, and a general interest in their religion was shown by the Beni-Israel. The advent of the Sassoons at Bombay brought the Beni-Israel into connection with the real life of Israel; and the family, as well as Christian missionaries, liberally supported religious, philanthropic, and educational establishments for the benefit of Beni-Israel. A special school for them was established in July, 1875, which, owing to the support given by the Anglo-Jewish Association, was enlarged in 1881, and now accommodates about 270 children.

As their native name implies, the original Beni-Israel were mainly oilmen or oil-pressers; but during the existence of the East India Company many of them adopted the career of soldier and obtained the highest rank, that of sirdar bahadur. Owing to the spread of education among them several have gone into learned professions and become engineers, doctors, and teachers.

The following are the chief places where Beni-Israel are to be found, with the population as given by the last accessible census (1891):

| Ahmadabad | 110 |

| Alibag | 90 |

| Ambepore | 39 |

| Bombay | 5,021 |

| Borlai | 51 |

| Karachi | 130 |

| Panwell | 301 |

| Pen | 182 |

| Poinad | 49 |

| Puna | 350 |

| Rahoon | 191 |

| Revadanda | 192 |

| Roha Ashtami | 232 |

Of recent years many works suitable for instruction have been translated into Mahrati for the benefit of the Beni-Israel, chiefly by the exertions of Joseph Ezekiel, whose works cover the whole cycle of Jewish ritual and liturgy, besides treatises on the Jewish religion and text books of Hebrew grammar. In addition to these, several newspapers in Mahrati were published, among them the "Bene Israelite" (Lamp of Judaism).

The task of determining with any degree of exactness the amount of Jewish blood that at present pervades the Beni-Israel is a very difficult one. In appearance they differ but slightly from their neighbors. They themselves are proud of their purity of descent, and point to the care taken by Jews of Cochin to separate the Black Jews, or proselytes, from the White. The use of the word "Ramzan" for the feast of the month of Elul might seem to indicate that they were originally Mohammedans, and were converted to Judaism by David Rahabi; but, on the other hand, it may have been the word only that was adopted, the custom of fasting during that month being derived from the Sephardic ritual, which is that current in Cochin. If originally Jews, the Beni-Israel retained very little of Jewish custom until the revival under Divekar, except the institution of the Sabbath, the repetition of the Shema', and the rite of circumcision; but in this they resemble the Jews in China, who appear to have kept their purity of descent almost up to the present time. For a full discussion of this question, see Cochin .

- Wilson, Appeal for the Christian Education of the Beni-Israel, 1806;

- idem, Lands of the Bible, ii. 667-676;

- Benjamin II., Eight Years in Asia, ch. xviii.-xix.;

- Ritter, Erdkunde, Asien II., § v., i. 595-601;

- J. Sapphir, Ibn Safir, 1875, ii.;

- Bombay Gazetteer, xviii. 506-536, Puna;

- E. Schlagintweit, in Westermann's Illustrirte Deutsche Monatsschrift;

- Jewish Chronicle, Aug. 31, Sept. 7, Oct. 12, 1888;

- H. Samuel, Sketch of Beni-Israel, 1889;

- Jacobs, Jewish Year Book, 1900-1, pp. 506-560.

Categories: [Jewish encyclopedia 1906]

↧ Download as ZWI file | Last modified: 09/04/2022 18:09:09 | 133 views

☰ Source: https://www.jewishencyclopedia.com/articles/2944-beni-israel.html | License: Public domain

ZWI signed:

ZWI signed: KSF

KSF