Marburg Virus Disease

From Mdwiki

From Mdwiki | Marburg virus disease | |

|---|---|

| Other names: Marburg hemorrhagic fever | |

| |

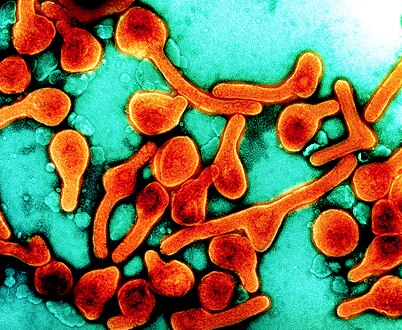

| Transmission electron micrograph of Marburg virus | |

| Symptoms | Fever, headache, muscle pain[1] |

| Complications | Liver failure, delirium, pancreatitis, bleeding[1] |

| Usual onset | 5-10 days after exposure[1] |

| Causes | Marburgvirus[2] |

| Risk factors | Contact with bats or infected bodily fluids[3] |

| Diagnostic method | Blood test[4] |

| Differential diagnosis | Malaria, typhoid fever, Ebola virus disease[1][5] |

| Treatment | Supportive care[5] |

| Frequency | Rare (588 cases 1967 to 2018)[6][5] |

| Deaths | ~50% death rate[5] |

Marburg virus disease (MVD), formerly Marburg hemorrhagic fever, is a severe type of viral hemorrhagic fever in humans.[5] Initial symptoms typically include fever, headache, and muscle pain.[1] A few days later a rash, vomiting, diarrhea, and abdominal pain may occur.[1] Onset of symptoms is typically 5 to 10 days following exposure.[1] Complications may include liver failure, delirium, pancreatitis, and severe bleeding.[1]

The cause is Marburgvirus, of which there are two types Marburg virus (MARV) and Ravn virus (RAVV).[2] These viruses normally circulates among African fruit bats, without resulting in ill affects.[6] Spread can occur from these bats to people and than between people.[5] Spread between people is by direct or indirect contact with contaminated body fluids, including during sex.[3][5] Diagnosis is by blood tests.[4] It presents similar to Ebola virus disease (EVD).[5]

Prevention involves avoiding bats in central Africa and using appropriate personal protective equipment when caring for sick people.[7] Treatment involves supportive care and this improves outcomes.[5] This may include intravenous fluids, blood products, oxygen therapy, and electrolytes.[8] About half of those who are infected die as a result.[5]

MVD is rare.[6] It generally occurs as outbreaks within Africa.[6] The disease was initially recognized in 1967 and since than 588 cases have been diagnosed.[6][5] Other primates may also be affected.[6]

Signs and symptoms[edit | edit source]

A maculopapular rash, petechiae, purpura, ecchymoses, and hematomas (especially around needle injection sites) are typical hemorrhagic manifestations. However, contrary to popular belief, hemorrhage does not lead to hypovolemia and is not the cause of death (total blood loss is minimal except during labor). Instead, death occurs due to multiple organ dysfunction syndrome (MODS) due to fluid redistribution, hypotension, disseminated intravascular coagulation, and focal tissue necroses.[10][11][12][13][14][15][16][17][18]

Phases of Marburg virus disease are described below. Note that phases overlap due to variability between cases.

- Incubation: 2–21 days, averaging 5–9 days.[19]

- Generalization Phase: Day 1 up to Day 5 from onset of clinical symptoms. MHF presents with a high fever 104 °F (~40˚C) and a sudden, severe headache, with accompanying chills, fatigue, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, pharyngitis, maculopapular rash, abdominal pain, conjunctivitis, and malaise.[19]

- Early Organ Phase: Day 5 up to Day 13. Symptoms include prostration, dyspnea, edema, conjunctival injection, viral exanthema, and CNS symptoms, including encephalitis, confusion, delirium, apathy, and aggression. Hemorrhagic symptoms typically occur late and herald the end of the early organ phase, leading either to eventual recovery or worsening and death. Symptoms include bloody stools, ecchymoses, blood leakage from venipuncture sites, mucosal and visceral hemorrhaging, and possibly hematemesis.[19]

- Late Organ Phase: Day 13 up to Day 21+. Symptoms bifurcate into two constellations for survivors and fatal cases. Survivors will enter a convalescence phase, experiencing myalgia, fibromyalgia, hepatitis, asthenia, ocular symptoms, and psychosis. Fatal cases continue to deteriorate, experiencing continued fever, obtundation, coma, convulsions, diffuse coagulopathy, metabolic disturbances, shock and death, with death typically occurring between days 8 and 16.[19]

Causes[edit | edit source]

MVD is caused by two viruses; Marburg virus (MARV) and Ravn virus (RAVV), family Filoviridae.[20]

Marburgviruses are endemic in arid woodlands of equatorial Africa.[21][22][23] Most marburgvirus infections were repeatedly associated with people visiting natural caves or working in mines. In 2009, the successful isolation of infectious MARV and RAVV was reported from healthy Egyptian rousette bats caught in caves.[24] This isolation strongly suggests that Old World fruit bats are involved in the natural maintenance of marburgviruses and that visiting bat-infested caves is a risk factor for acquiring marburgvirus infections. Further studies are necessary to establish whether Egyptian rousettes are the actual hosts of MARV and RAVV or whether they get infected via contact with another animal and therefore serve only as intermediate hosts. Another risk factor is contact with nonhuman primates, although only one outbreak of MVD (in 1967) was due to contact with infected monkeys.[25]

Contrary to Ebola virus disease (EVD), which has been associated with heavy rains after long periods of dry weather,[22][26] triggering factors for spillover of marburgviruses into the human population have not yet been described.

Virology[edit | edit source]

| Species name | Virus name (Abbreviation) |

| Marburg marburgvirus* | Marburg virus (MARV; previously MBGV) |

| Ravn virus (RAVV; previously MARV-Ravn) | |

| "*" denotes the type species. | |

Genome[edit | edit source]

Like all mononegaviruses, marburgvirions contain non-infectious, linear nonsegmented, single-stranded RNA genomes of negative polarity that possesses inverse-complementary 3' and 5' termini, do not possess a 5' cap, are not polyadenylated, and are not covalently linked to a protein.[27] Marburgvirus genomes are approximately 19 kb long and contain seven genes in the order 3'-UTR-NP-VP35-VP40-GP-VP30-VP24-L-5'-UTR.[28]

Structure[edit | edit source]

Like all filoviruses, marburgvirions are filamentous particles that may appear in the shape of a shepherd's crook or in the shape of a "U" or a "6", and they may be coiled, toroid, or branched.[28] Marburgvirions are generally 80 nm in width, but vary somewhat in length. In general, the median particle length of marburgviruses ranges from 795–828 nm (in contrast to ebolavirions, whose median particle length was measured to be 974–1,086 nm ), but particles as long as 14,000 nm have been detected in tissue culture.[29] Marburgvirions consist of seven structural proteins. At the center is the helical ribonucleocapsid, which consists of the genomic RNA wrapped around a polymer of nucleoproteins (NP). Associated with the ribonucleoprotein is the RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (L) with the polymerase cofactor (VP35) and a transcription activator (VP30). The ribonucleoprotein is embedded in a matrix, formed by the major (VP40) and minor (VP24) matrix proteins. These particles are surrounded by a lipid membrane derived from the host cell membrane. The membrane anchors a glycoprotein (GP1,2) that projects 7 to 10 nm spikes away from its surface.[citation needed]

Replication[edit | edit source]

The marburgvirus life cycle begins with virion attachment to specific cell-surface receptors, followed by fusion of the virion envelope with cellular membranes and the concomitant release of the virus nucleocapsid into the cytosol. The virus RdRp partially uncoats the nucleocapsid and transcribes the genes into positive-stranded mRNAs, which are then translated into structural and nonstructural proteins. Marburgvirus L binds to a single promoter located at the 3' end of the genome. Transcription either terminates after a gene or continues to the next gene downstream. This means that genes close to the 3' end of the genome are transcribed in the greatest abundance, whereas those toward the 5' end are least likely to be transcribed. The gene order is therefore a simple but effective form of transcriptional regulation. The most abundant protein produced is the nucleoprotein, whose concentration in the cell determines when L switches from gene transcription to genome replication. Replication results in full-length, positive-stranded antigenomes that are in turn transcribed into negative-stranded virus progeny genome copies. Newly synthesized structural proteins and genomes self-assemble and accumulate near the inside of the cell membrane. Virions bud off from the cell, gaining their envelopes from the cellular membrane they bud from. The mature progeny particles then infect other cells to repeat the cycle.[30]

Diagnosis[edit | edit source]

MVD is clinically indistinguishable from Ebola virus disease (EVD), and it can also easily be confused with many other diseases prevalent in Equatorial Africa, such as other viral hemorrhagic fevers, falciparum malaria, typhoid fever, shigellosis, rickettsial diseases such as typhus, cholera, gram-negative sepsis, borreliosis such as relapsing fever or EHEC enteritis. Other infectious diseases that ought to be included in the differential diagnosis include leptospirosis, scrub typhus, plague, Q fever, candidiasis, histoplasmosis, trypanosomiasis, visceral leishmaniasis, hemorrhagic smallpox, measles, and fulminant viral hepatitis. Non-infectious diseases that can be confused with MVD are acute promyelocytic leukemia, hemolytic uremic syndrome, snake envenomation, clotting factor deficiencies/platelet disorders, thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura, hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia, Kawasaki disease, and even warfarin intoxication.[31][32][33][34] The most important indicator that may lead to the suspicion of MVD at clinical examination is the medical history of the patient, in particular the travel and occupational history (which countries and caves were visited?) and the patient's exposure to wildlife (exposure to bats or bat excrements?). MVD can be confirmed by isolation of marburgviruses from or by detection of marburgvirus antigen or genomic or subgenomic RNAs in patient blood or serum samples during the acute phase of MVD. Marburgvirus isolation is usually performed by inoculation of grivet kidney epithelial Vero E6 or MA-104 cell cultures or by inoculation of human adrenal carcinoma SW-13 cells, all of which react to infection with characteristic cytopathic effects.[35][36] Filovirions can easily be visualized and identified in cell culture by electron microscopy due to their unique filamentous shapes, but electron microscopy cannot differentiate the various filoviruses alone despite some overall length differences.[29] Immunofluorescence assays are used to confirm marburgvirus presence in cell cultures. During an outbreak, virus isolation and electron microscopy are most often not feasible options. The most common diagnostic methods are therefore RT-PCR[37][38][39][40][41] in conjunction with antigen-capture ELISA,[42][43][44] which can be performed in field or mobile hospitals and laboratories. Indirect immunofluorescence assays (IFAs) are not used for diagnosis of MVD in the field anymore.[citation needed]

Classification[edit | edit source]

Marburg virus disease (MVD) is the official name listed in the World Health Organization's International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems 10 (ICD-10) for the human disease caused by any of the two marburgviruses Marburg virus (MARV) and Ravn virus (RAVV). In the scientific literature, Marburg hemorrhagic fever (MHF) is often used as an unofficial alternative name for the same disease. Both disease names are derived from the German city Marburg, where MARV was first discovered.[25]

Prevention[edit | edit source]

There are currently no approved vaccines for the prevention of MVD. Many candidates are in development.[45][46][47] Of those, the most promising ones are DNA vaccines[48] or based on Venezuelan equine encephalitis virus replicons,[49] vesicular stomatitis Indiana virus (VSIV)[46][50] or filovirus-like particles (VLPs)[47] as all of these candidates could protect nonhuman primates from marburgvirus-induced disease. DNA vaccines have entered clinical trials.[51] Marburgviruses are highly infectious, but not very contagious. They do not get transmitted by aerosol during natural MVD outbreaks. Due to the absence of an approved vaccine, prevention of MVD therefore relies predominantly on quarantine of confirmed or high probability cases, proper personal protective equipment, and sterilization and disinfection.[citation needed]

Endemic zones[edit | edit source]

The natural maintenance hosts of marburg viruses remain to be identified unequivocally. However, the isolation of both MARV and RAVV from bats and the association of several MVD outbreaks with bat-infested mines or caves strongly suggests that bats are involved in marburg virus transmission to humans. Avoidance of contact with bats and abstaining from visits to caves is highly recommended, but may not be possible for those working in mines or people dependent on bats as a food source.[citation needed]

During outbreaks[edit | edit source]

Since marburgviruses are not spread via aerosol, the most straightforward prevention method during MVD outbreaks is to avoid direct (skin-to-skin) contact with patients, their excretions and body fluids, and any possibly contaminated materials and utensils. Patients should be isolated, but still are safe to be visited by family members. Medical staff should be trained in and apply strict barrier nursing techniques (disposable face mask, gloves, goggles, and a gown at all times). Traditional burial rituals, especially those requiring embalming of bodies, should be discouraged or modified, ideally with the help of local traditional healers.[52]

Laboratory measures[edit | edit source]

Marburgviruses are World Health Organization Risk Group 4 Pathogens, requiring Biosafety Level 4-equivalent containment,[53] laboratory researchers have to be properly trained in BSL-4 practices and wear proper personal protective equipment.

Treatment[edit | edit source]

There is currently no specific therapy for MVD. Treatment is primarily supportive in nature and includes minimizing invasive procedures, balancing fluids and electrolytes to counter dehydration, administration of anticoagulants early in infection to prevent or control disseminated intravascular coagulation, administration of procoagulants late in infection to control hemorrhaging, maintaining oxygen levels, pain management, and administration of antibiotics or antimycotics to treat secondary infections.[54][55] Experimentally, recombinant vesicular stomatitis Indiana virus (VSIV) expressing the glycoprotein of MARV has been used successfully in nonhuman primate models as post-exposure prophylaxis.[56] Experimental therapeutic regimens relying on antisense technology have shown promise, with phosphorodiamidate morpholino oligomers (PMOs) targeting the MARV genome [57] New therapies from Sarepta [58] and Tekmira [59] have also been successfully used in humans as well as primates.

Prognosis[edit | edit source]

Prognosis is generally poor. If a patient survives, recovery may be prompt and complete, or protracted with sequelae, such as orchitis, hepatitis, uveitis, parotitis, desquamation or alopecia. Importantly, MARV is known to be able to persist in some survivors and to either reactivate and cause a secondary bout of MVD or to be transmitted via sperm, causing secondary cases of infection and disease.[17][60][61][62]

Of the 252 people who contracted Marburg during the 2004–2005 outbreak of a particularly virulent serotype in Angola, 227 died, for a case fatality rate of 90%.[63] Although all age groups are susceptible to infection, children are rarely infected. In the 1998–2000 Congo epidemic, only 8% of the cases were children less than 5 years old.[64]

Epidemiology[edit | edit source]

| Year | Country | Virus | Cases | Deaths | % deaths | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1967 | MARV | 31 | 7 | 23% | ||

| 1975 | MARV | 3 | 1 | 33% | ||

| 1980 | MARV | 2 | 1 | 50% | ||

| 1987 | RAVV | 1 | 1 | 100% | ||

| 1988 | MARV | 1 | 1 | 100% | ||

| 1990 | MARV | 1 | 0 | 0% | ||

| 1998–2000 | MARV & RAVV | 154 | 128 | 83% | ||

| 2004–2005 | MARV | 252 | 227 | 90% | ||

| 2007 | MARV & RAVV | 4 | 1 | 25% | [66] | |

| 2008 | MARV | 2 | 1 | 50% | [67] | |

| 2012 | MARV | 18 | 9 | 50% | [68][69] | |

| 2014 | MARV | 1 | 1 | 100% | [70][71] | |

| 2017 | MARV | 3 | 3 | 100% | [72] |

1967 outbreak[edit | edit source]

MVD was first documented in 1967, when 31 people became ill in the German towns of Marburg and Frankfurt am Main, and in Belgrade, Yugoslavia. The outbreak involved 25 primary MARV infections and seven deaths, and six nonlethal secondary cases. The outbreak was traced to infected grivets (species Chlorocebus aethiops) imported from an undisclosed location in Uganda and used in developing poliomyelitis vaccines. The monkeys were received by Behringwerke, a Marburg company founded by the first winner of the Nobel Prize in Medicine, Emil von Behring. The company, which at the time was owned by Hoechst, was originally set up to develop sera against tetanus and diphtheria. Primary infections occurred in Behringwerke laboratory staff while working with grivet tissues or tissue cultures without adequate personal protective equipment. Secondary cases involved two physicians, a nurse, a post-mortem attendant, and the wife of a veterinarian. All secondary cases had direct contact, usually involving blood, with a primary case. Both physicians became infected through accidental skin pricks when drawing blood from patients.[73][74][75][76] A popular science account of this outbreak can be found in Laurie Garrett’s book The Coming Plague.[77]

1975 cases[edit | edit source]

In 1975, an Australian tourist became infected with MARV in Rhodesia (today Zimbabwe). He died in a hospital in Johannesburg, South Africa. His girlfriend and an attending nurse were subsequently infected with MVD, but survived.[15][78][79]

1980 cases[edit | edit source]

A case of MARV infection occurred in 1980 in Kenya. A French man, who worked as an electrical engineer in a sugar factory in Nzoia (close to Bungoma) at the base of Mount Elgon (which contains Kitum Cave), became infected by unknown means and died shortly after admission to Nairobi Hospital. The attending physician contracted MVD, but survived.[80] A popular science account of these cases can be found in Richard Preston’s book The Hot Zone (the French man is referred to under the pseudonym “Charles Monet”, whereas the physician is identified under his real name, Shem Musoke).[81]

1987 case[edit | edit source]

In 1987, a single lethal case of RAVV infection occurred in a 15-year-old Danish boy, who spent his vacation in Kisumu, Kenya. He had visited Kitum Cave on Mount Elgon prior to travelling to Mombasa, where he developed clinical signs of infection. The boy died after transfer to Nairobi Hospital.[16] A popular science account of this case can be found in Richard Preston’s book The Hot Zone (the boy is referred to under the pseudonym “Peter Cardinal”).[81]

1988 laboratory infection[edit | edit source]

In 1988, researcher Nikolai Ustinov infected himself lethally with MARV after accidentally pricking himself with a syringe used for inoculation of guinea pigs. The accident occurred at the Scientific-Production Association "Vektor" (today the State Research Center of Virology and Biotechnology "Vektor") in Koltsovo, USSR (today Russia).[82] Very little information is publicly available about this MVD case because Ustinov's experiments were classified. A popular science account of this case can be found in Ken Alibek’s book Biohazard.[83]

1990 laboratory infection[edit | edit source]

Another laboratory accident occurred at the Scientific-Production Association "Vektor" (today the State Research Center of Virology and Biotechnology "Vektor") in Koltsovo, USSR, when a scientist contracted MARV by unknown means.[17]

1998–2000 outbreak[edit | edit source]

A major MVD outbreak occurred among illegal gold miners around Goroumbwa mine in Durba and Watsa, Democratic Republic of Congo from 1998 to 2000, when co-circulating MARV and RAVV caused 154 cases of MVD and 128 deaths. The outbreak ended with the flooding of the mine.[84][85]

2004–2005 outbreak[edit | edit source]

In early 2005, the World Health Organization (WHO) began investigating an outbreak of viral hemorrhagic fever in Angola, which was centered in the northeastern Uíge Province but also affected many other provinces. The Angolan government had to ask for international assistance, pointing out that there were only approximately 1,200 doctors in the entire country, with some provinces having as few as two. Health care workers also complained about a shortage of personal protective equipment such as gloves, gowns, and masks. Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) reported that when their team arrived at the provincial hospital at the center of the outbreak, they found it operating without water and electricity. Contact tracing was complicated by the fact that the country's roads and other infrastructure were devastated after nearly three decades of civil war and the countryside remained littered with land mines. Americo Boa Vida Hospital in the Angolan capital Luanda set up a special isolation ward to treat infected people from the countryside. Unfortunately, because MVD often results in death, some people came to view hospitals and medical workers with suspicion and treated helpers with hostility. For instance, a specially-equipped isolation ward at the provincial hospital in Uíge was reported to be empty during much of the epidemic, even though the facility was at the center of the outbreak. WHO was forced to implement what it described as a "harm reduction strategy", which entailed distributing disinfectants to affected families who refused hospital care. Of the 252 people who contracted MVD during outbreak, 227 died.[18][86][87][88][89][90][91]

2007 cases[edit | edit source]

In 2007, four miners became infected with marburgviruses in Kamwenge District, Uganda. The first case, a 29-year-old man, became symptomatic on July 4, 2007, was admitted to a hospital on July 7, and died on July 13. Contact tracing revealed that the man had had prolonged close contact with two colleagues (a 22-year-old man and a 23-year-old man), who experienced clinical signs of infection before his disease onset. Both men had been admitted to hospitals in June and survived their infections, which were proven to be due to MARV. A fourth, 25-year-old man, developed MVD clinical signs in September and was shown to be infected with RAVV. He also survived the infection.[24][92]

2008 cases[edit | edit source]

On July 10, 2008, the Netherlands National Institute for Public Health and the Environment reported that a 41-year-old Dutch woman, who had visited Python Cave in Maramagambo Forest during her holiday in Uganda suffered of MVD due to MARV infection, and had been admitted to a hospital in the Netherlands. The woman died under treatment in the Leiden University Medical Centre in Leiden on July 11. The Ugandan Ministry of Health closed the cave after this case.[93] On January 9 of that year an infectious diseases physician notified the Colorado Department of Public Health and the Environment that a 44-year-old American woman who had returned from Uganda had been hospitalized with a fever of unknown origin. At the time, serologic testing was negative for viral hemorrhagic fever. She was discharged on January 19, 2008. After the death of the Dutch patient and the discovery that the American woman had visited Python Cave, further testing confirmed the patient demonstrated MARV antibodies and RNA.[94]

2017 Uganda outbreak[edit | edit source]

In October 2017 an outbreak of Marburg virus disease was detected in Kween District, Eastern Uganda. All three initial cases (belonging to one family – two brothers and one sister) had died by 3 November. The fourth case – a health care worker – developed symptoms on 4 November and was admitted to a hospital. The first confirmed case traveled to Kenya before the death. A close contact of the second confirmed case traveled to Kampala. It is reported that several hundred people may have been exposed to infection.[95][96]

See also[edit | edit source]

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 1.6 1.7 "Signs and Symptoms | Marburg Hemorrhagic Fever (Marburg HF) | CDC". www.cdc.gov. 25 February 2019. Archived from the original on 20 March 2021. Retrieved 25 March 2021.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Spickler, Anna. "Ebolavirus and Marburgvirus Infections" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2015-04-30. Retrieved 2014-10-19.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 "Transmission | Marburg Hemorrhagic Fever (Marburg HF) | CDC". www.cdc.gov. 25 February 2019. Archived from the original on 19 March 2021. Retrieved 25 March 2021.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 "Ebola Virus Disease & Marburg Virus Disease - Chapter 3 - 2018 Yellow Book | Travelers' Health | CDC". wwwnc.cdc.gov. Archived from the original on 19 July 2019. Retrieved 19 July 2019.

- ↑ 5.00 5.01 5.02 5.03 5.04 5.05 5.06 5.07 5.08 5.09 5.10 "Marburg virus disease". www.who.int. Archived from the original on 11 April 2020. Retrieved 8 February 2020.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 6.4 6.5 "About Marburg Hemorrhagic Fever | Marburg Hemorrhagic Fever (Marburg HF) | CDC". www.cdc.gov. 25 February 2019. Archived from the original on 20 March 2021. Retrieved 25 March 2021.

- ↑ "Prevention | Marburg Hemorrhagic Fever (Marburg HF) | CDC". www.cdc.gov. 25 February 2019. Archived from the original on 20 March 2021. Retrieved 25 March 2021.

- ↑ "Treatment | Marburg Hemorrhagic Fever (Marburg HF) | CDC". www.cdc.gov. 25 February 2019. Archived from the original on 19 March 2021. Retrieved 25 March 2021.

- ↑ "Details - Public Health Image Library(PHIL)". phil.cdc.gov. Archived from the original on 28 August 2021. Retrieved 25 March 2021.

- ↑ Martini, G. A. (1971). "Marburg Virus Disease. Clinical Syndrome". In Martini, G. A.; Siegert, R. (eds.). Marburg Virus Disease. Berlin, Germany: Springer-Verlag. pp. 1–9. ISBN 978-0-387-05199-4{{inconsistent citations}}

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: postscript (link) - ↑ Todorovitch, K.; Mocitch, M.; Klašnja, R. (1971). "Clinical Picture of Two Patients Infected by the Marburg Vervet Virus". In Martini, G. A.; Siegert, R. (eds.). Marburg Virus Disease. Berlin, Germany: Springer-Verlag. pp. 19–23. ISBN 978-0-387-05199-4{{inconsistent citations}}

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: postscript (link) - ↑ Egbring, R.; Slenczka, W.; Baltzer, G. (1971). "Clinical Manifestations and Mechanisms of the Haemorrhagic Diathesis in Marburg Virus Disease". In Martini, G. A.; Siegert, R. (eds.). Marburg Virus Disease. Berlin, Germany: Springer-Verlag. pp. 41–9. ISBN 978-0-387-05199-4{{inconsistent citations}}

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: postscript (link) - ↑ Havemann, K.; Schmidt, H. A. (1971). "Haematological Findings in Marburg Virus Disease: Evidence for Involvement of the Immunological System". In Martini, G. A.; Siegert, R. (eds.). Marburg Virus Disease. Berlin, Germany: Springer-Verlag. pp. 34–40. ISBN 978-0-387-05199-4{{inconsistent citations}}

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: postscript (link) - ↑ Stille, W.; Böhle, E. (1971). "Clinical Course and Prognosis of Marburg Virus ("Green Monkey") Disease". In Martini, G. A.; Siegert, R. (eds.). Marburg Virus Disease. Berlin, Germany: Springer-Verlag. pp. 10–18. ISBN 978-0-387-05199-4{{inconsistent citations}}

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: postscript (link) - ↑ 15.0 15.1 Gear, J. S.; Cassel, G. A.; Gear, A. J.; Trappler, B.; Clausen, L.; Meyers, A. M.; Kew, M. C.; Bothwell, T. H.; Sher, R.; Miller, G. B.; Schneider, J.; Koornhof, H. J.; Gomperts, E. D.; Isaäcson, M.; Gear, J. H. (1975). "Outbreake of Marburg virus disease in Johannesburg". British Medical Journal. 4 (5995): 489–493. doi:10.1136/bmj.4.5995.489. PMC 1675587. PMID 811315.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 Johnson, E. D.; Johnson, B. K.; Silverstein, D.; Tukei, P.; Geisbert, T. W.; Sanchez, A. N.; Jahrling, P. B. (1996). "Characterization of a new Marburg virus isolated from a 1987 fatal case in Kenya". Archives of Virology. Supplementum. 11: 101–114. doi:10.1007/978-3-7091-7482-1_10. ISBN 978-3-211-82829-8. PMID 8800792.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 17.2 Nikiforov, V. V.; Turovskiĭ, I.; Kalinin, P. P.; Akinfeeva, L. A.; Katkova, L. R.; Barmin, V. S.; Riabchikova, E. I.; Popkova, N. I.; Shestopalov, A. M.; Nazarov, V. P. (1994). "A case of a laboratory infection with Marburg fever". Zhurnal Mikrobiologii, Epidemiologii, I Immunobiologii (3): 104–106. PMID 7941853.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 Roddy, P.; Thomas, S. L.; Jeffs, B.; Nascimento Folo, P.; Pablo Palma, P.; Moco Henrique, B.; Villa, L.; Damiao Machado, F. P.; Bernal, O.; Jones, S. M.; Strong, J. E.; Feldmann, H.; Borchert, M. (2010). "Factors Associated with Marburg Hemorrhagic Fever: Analysis of Patient Data from Uige, Angola". The Journal of Infectious Diseases. 201 (12): 1909–1918. doi:10.1086/652748. PMC 3407405. PMID 20441515.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 19.2 19.3 Mehedi, Masfique; Allison Groseth; Heinz Feldmann; Hideki Ebihara (September 2011). "Clinical aspects of Marburg hemorrhagic fever". Future Virol. 6 (9): 1091–1106. doi:10.2217/fvl.11.79. PMC 3201746. PMID 22046196.

- ↑ Singh, edited by Sunit K.; Ruzek, Daniel (2014). Viral hemorrhagic fevers. Boca Raton: CRC Press. p. 458. ISBN 9781439884317. Archived from the original on 28 August 2021. Retrieved 28 October 2017.

- ↑ Peterson, A. T.; Bauer, J. T.; Mills, J. N. (2004). "Ecologic and Geographic Distribution of Filovirus Disease". Emerging Infectious Diseases. 10 (1): 40–47. doi:10.3201/eid1001.030125. PMC 3322747. PMID 15078595.

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 Pinzon, E.; Wilson, J. M.; Tucker, C. J. (2005). "Climate-based health monitoring systems for eco-climatic conditions associated with infectious diseases". Bulletin de la Société de Pathologie Exotique. 98 (3): 239–243. PMID 16267968.

- ↑ Peterson, A. T.; Lash, R. R.; Carroll, D. S.; Johnson, K. M. (2006). "Geographic potential for outbreaks of Marburg hemorrhagic fever". The American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. 75 (1): 9–15. doi:10.4269/ajtmh.2006.75.1.0750009. PMID 16837700.

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 Towner, J. S.; Amman, B. R.; Sealy, T. K.; Carroll, S. A. R.; Comer, J. A.; Kemp, A.; Swanepoel, R.; Paddock, C. D.; Balinandi, S.; Khristova, M. L.; Formenty, P. B.; Albarino, C. G.; Miller, D. M.; Reed, Z. D.; Kayiwa, J. T.; Mills, J. N.; Cannon, D. L.; Greer, P. W.; Byaruhanga, E.; Farnon, E. C.; Atimnedi, P.; Okware, S.; Katongole-Mbidde, E.; Downing, R.; Tappero, J. W.; Zaki, S. R.; Ksiazek, T. G.; Nichol, S. T.; Rollin, P. E. (2009). Fouchier, Ron A. M. (ed.). "Isolation of Genetically Diverse Marburg Viruses from Egyptian Fruit Bats". PLOS Pathogens. 5 (7): e1000536. doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.1000536. PMC 2713404. PMID 19649327.

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 Siegert, R.; Shu, H. L.; Slenczka, W.; Peters, D.; Müller, G. (2009). "Zur Ätiologie einer unbekannten, von Affen ausgegangenen menschlichen Infektionskrankheit". Deutsche Medizinische Wochenschrift. 92 (51): 2341–2343. doi:10.1055/s-0028-1106144. PMID 4294540.

- ↑ Tucker, C. J.; Wilson, J. M.; Mahoney, R.; Anyamba, A.; Linthicum, K.; Myers, M. F. (2002). "Climatic and Ecological Context of the 1994–1996 Ebola Outbreaks". Photogrammetric Engineering and Remote Sensing. 68 (2): 144–52.

- ↑ Pringle, C. R. (2005). "Order Mononegavirales". In Fauquet, C. M.; Mayo, M. A.; Maniloff, J.; Desselberger, U.; Ball, L. A. (eds.). Virus Taxonomy—Eighth Report of the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses. San Diego, USA: Elsevier/Academic Press. pp. 609–614. ISBN 978-0-12-370200-5{{inconsistent citations}}

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: postscript (link) - ↑ 28.0 28.1 Kiley, M. P.; Bowen, E. T.; Eddy, G. A.; Isaäcson, M.; Johnson, K. M.; McCormick, J. B.; Murphy, F. A.; Pattyn, S. R.; Peters, D.; Prozesky, O. W.; Regnery, R. L.; Simpson, D. I.; Slenczka, W.; Sureau, P.; Van Der Groen, G.; Webb, P. A.; Wulff, H. (1982). "Filoviridae: A taxonomic home for Marburg and Ebola viruses?". Intervirology. 18 (1–2): 24–32. doi:10.1159/000149300. PMID 7118520.

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 Geisbert, T. W.; Jahrling, P. B. (1995). "Differentiation of filoviruses by electron microscopy". Virus Research. 39 (2–3): 129–150. doi:10.1016/0168-1702(95)00080-1. PMID 8837880. Archived from the original on 2019-12-17. Retrieved 2019-06-29.

- ↑ Feldmann, H.; Geisbert, T. W.; Jahrling, P. B.; Klenk, H.-D.; Netesov, S. V.; Peters, C. J.; Sanchez, A.; Swanepoel, R.; Volchkov, V. E. (2005). "Family Filoviridae". In Fauquet, C. M.; Mayo, M. A.; Maniloff, J.; Desselberger, U.; Ball, L. A. (eds.). Virus Taxonomy—Eighth Report of the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses. San Diego, USA: Elsevier/Academic Press. pp. 645–653. ISBN 978-0-12-370200-5{{inconsistent citations}}

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: postscript (link) - ↑ Gear, J. H. (1989). "Clinical aspects of African viral hemorrhagic fevers". Reviews of Infectious Diseases. 11 Suppl 4: S777–S782. doi:10.1093/clinids/11.supplement_4.s777. PMID 2665013.

- ↑ Gear, J. H.; Ryan, J.; Rossouw, E. (1978). "A consideration of the diagnosis of dangerous infectious fevers in South Africa". South African Medical Journal. 53 (7): 235–237. PMID 565951.

- ↑ Grolla, A.; Lucht, A.; Dick, D.; Strong, J. E.; Feldmann, H. (2005). "Laboratory diagnosis of Ebola and Marburg hemorrhagic fever". Bulletin de la Société de Pathologie Exotique. 98 (3): 205–209. PMID 16267962.

- ↑ Bogomolov, B. P. (1998). "Differential diagnosis of infectious diseases with hemorrhagic syndrome". Terapevticheskii Arkhiv. 70 (4): 63–68. PMID 9612907.

- ↑ Hofmann, H.; Kunz, C. (1968). ""Marburg virus" (Vervet monkey disease agent) in tissue cultures". Zentralblatt für Bakteriologie, Parasitenkunde, Infektionskrankheiten und Hygiene. 1. Abt. Medizinisch-hygienische Bakteriologie, Virusforschung und Parasitologie. Originale. 208 (1): 344–347. PMID 4988544.

- ↑ Ksiazek, Thomas G. (1991). "Laboratory diagnosis of filovirus infections in nonhuman primates". Lab Animal. 20 (7): 34–6.

- ↑ Gibb, T.; Norwood Jr, D. A.; Woollen, N.; Henchal, E. A. (2001). "Development and evaluation of a fluorogenic 5′-nuclease assay to identify Marburg virus". Molecular and Cellular Probes. 15 (5): 259–266. doi:10.1006/mcpr.2001.0369. PMID 11735297. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2021-08-28. Retrieved 2019-06-29.

- ↑ Drosten, C.; Göttig, S.; Schilling, S.; Asper, M.; Panning, M.; Schmitz, H.; Günther, S. (2002). "Rapid Detection and Quantification of RNA of Ebola and Marburg Viruses, Lassa Virus, Crimean-Congo Hemorrhagic Fever Virus, Rift Valley Fever Virus, Dengue Virus, and Yellow Fever Virus by Real-Time Reverse Transcription-PCR". Journal of Clinical Microbiology. 40 (7): 2323–2330. doi:10.1128/jcm.40.7.2323-2330.2002. PMC 120575. PMID 12089242.

- ↑ Weidmann, M.; Mühlberger, E.; Hufert, F. T. (2004). "Rapid detection protocol for filoviruses". Journal of Clinical Virology. 30 (1): 94–99. doi:10.1016/j.jcv.2003.09.004. PMID 15072761.

- ↑ Zhai, J.; Palacios, G.; Towner, J. S.; Jabado, O.; Kapoor, V.; Venter, M.; Grolla, A.; Briese, T.; Paweska, J.; Swanepoel, R.; Feldmann, H.; Nichol, S. T.; Lipkin, W. I. (2006). "Rapid Molecular Strategy for Filovirus Detection and Characterization". Journal of Clinical Microbiology. 45 (1): 224–226. doi:10.1128/JCM.01893-06. PMC 1828965. PMID 17079496.

- ↑ Weidmann, M.; Hufert, F. T.; Sall, A. A. (2007). "Viral load among patients infected with Marburgvirus in Angola". Journal of Clinical Virology. 39 (1): 65–66. doi:10.1016/j.jcv.2006.12.023. PMID 17360231.

- ↑ Saijo, M.; Niikura, M.; Maeda, A.; Sata, T.; Kurata, T.; Kurane, I.; Morikawa, S. (2005). "Characterization of monoclonal antibodies to Marburg virus nucleoprotein (NP) that can be used for NP-capture enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay". Journal of Medical Virology. 76 (1): 111–118. doi:10.1002/jmv.20332. PMID 15778962. S2CID 24207187.

- ↑ Saijo, M.; Niikura, M.; Ikegami, T.; Kurane, I.; Kurata, T.; Morikawa, S. (2006). "Laboratory Diagnostic Systems for Ebola and Marburg Hemorrhagic Fevers Developed with Recombinant Proteins". Clinical and Vaccine Immunology. 13 (4): 444–451. doi:10.1128/CVI.13.4.444-451.2006. PMC 1459631. PMID 16603611.

- ↑ Saijo, M.; Georges-Courbot, M. C.; Fukushi, S.; Mizutani, T.; Philippe, M.; Georges, A. J.; Kurane, I.; Morikawa, S. (2006). "Marburgvirus nucleoprotein-capture enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay using monoclonal antibodies to recombinant nucleoprotein: Detection of authentic Marburgvirus". Japanese Journal of Infectious Diseases. 59 (5): 323–325. PMID 17060700.

- ↑ Garbutt, M.; Liebscher, R.; Wahl-Jensen, V.; Jones, S.; Möller, P.; Wagner, R.; Volchkov, V.; Klenk, H. D.; Feldmann, H.; Ströher, U. (2004). "Properties of Replication-Competent Vesicular Stomatitis Virus Vectors Expressing Glycoproteins of Filoviruses and Arenaviruses". Journal of Virology. 78 (10): 5458–5465. doi:10.1128/JVI.78.10.5458-5465.2004. PMC 400370. PMID 15113924.

- ↑ 46.0 46.1 Daddario-Dicaprio, K. M.; Geisbert, T. W.; Geisbert, J. B.; Ströher, U.; Hensley, L. E.; Grolla, A.; Fritz, E. A.; Feldmann, F.; Feldmann, H.; Jones, S. M. (2006). "Cross-Protection against Marburg Virus Strains by Using a Live, Attenuated Recombinant Vaccine". Journal of Virology. 80 (19): 9659–9666. doi:10.1128/JVI.00959-06. PMC 1617222. PMID 16973570.

- ↑ 47.0 47.1 Swenson, D. L.; Warfield, K. L.; Larsen, T.; Alves, D. A.; Coberley, S. S.; Bavari, S. (2008). "Monovalent virus-like particle vaccine protects guinea pigs and nonhuman primates against infection with multiple Marburg viruses". Expert Review of Vaccines. 7 (4): 417–429. doi:10.1586/14760584.7.4.417. PMID 18444889. S2CID 23200723.

- ↑ Riemenschneider, J.; Garrison, A.; Geisbert, J.; Jahrling, P.; Hevey, M.; Negley, D.; Schmaljohn, A.; Lee, J.; Hart, M. K.; Vanderzanden, L.; Custer, D.; Bray, M.; Ruff, A.; Ivins, B.; Bassett, A.; Rossi, C.; Schmaljohn, C. (2003). "Comparison of individual and combination DNA vaccines for B. Anthracis, Ebola virus, Marburg virus and Venezuelan equine encephalitis virus". Vaccine. 21 (25–26): 4071–4080. doi:10.1016/S0264-410X(03)00362-1. PMID 12922144. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2021-08-28. Retrieved 2019-06-29.

- ↑ Hevey, M.; Negley, D.; Pushko, P.; Smith, J.; Schmaljohn, A. (Nov 1998). "Marburg virus vaccines based upon alphavirus replicons protect guinea pigs and nonhuman primates". Virology. 251 (1): 28–37. doi:10.1006/viro.1998.9367. ISSN 0042-6822. PMID 9813200.

- ↑ Jones, M.; Feldmann, H.; Ströher, U.; Geisbert, J. B.; Fernando, L.; Grolla, A.; Klenk, H. D.; Sullivan, N. J.; Volchkov, V. E.; Fritz, E. A.; Daddario, K. M.; Hensley, L. E.; Jahrling, P. B.; Geisbert, T. W. (2005). "Live attenuated recombinant vaccine protects nonhuman primates against Ebola and Marburg viruses". Nature Medicine. 11 (7): 786–790. doi:10.1038/nm1258. PMID 15937495. S2CID 5450135.

- ↑ "Ebola/Marburg Vaccine Development" (Press release). National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases. 2008-09-15. Archived from the original on 2010-03-06.

- ↑ Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and World Health Organization (1998). Infection Control for Viral Haemorrhagic Fevers in the African Health Care Setting (PDF). Atlanta, Georgia, USA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2009-05-07. Retrieved 2009-05-31.

- ↑ US Department of Health and Human Services. "Biosafety in Microbiological and Biomedical Laboratories (BMBL) 5th Edition". Archived from the original on 2020-04-23. Retrieved 2011-10-16.

- ↑ Bausch, D. G.; Feldmann, H.; Geisbert, T. W.; Bray, M.; Sprecher, A. G.; Boumandouki, P.; Rollin, P. E.; Roth, C.; Winnipeg Filovirus Clinical Working Group (2007). "Outbreaks of Filovirus Hemorrhagic Fever: Time to Refocus on the Patient". The Journal of Infectious Diseases. 196: S136–S141. doi:10.1086/520542. PMID 17940941.

- ↑ Jeffs, B. (2006). "A clinical guide to viral haemorrhagic fevers: Ebola, Marburg and Lassa". Tropical Doctor. 36 (1): 1–4. doi:10.1258/004947506775598914. PMID 16483416. S2CID 101015.

- ↑ Daddario-Dicaprio, K. M.; Geisbert, T. W.; Ströher, U.; Geisbert, J. B.; Grolla, A.; Fritz, E. A.; Fernando, L.; Kagan, E.; Jahrling, P. B.; Hensley, L. E.; Jones, S. M.; Feldmann, H. (2006). "Postexposure protection against Marburg haemorrhagic fever with recombinant vesicular stomatitis virus vectors in non-human primates: An efficacy assessment". The Lancet. 367 (9520): 1399–1404. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68546-2. PMID 16650649. S2CID 14039727. Archived from the original on 2017-09-27. Retrieved 2018-04-29.

- ↑ Warren, T. K.; Warfield, K. L.; Wells, J.; Swenson, D. L.; Donner, K. S.; Van Tongeren, S. A.; Garza, N. L.; Dong, L.; Mourich, D. V.; Crumley, S.; Nichols, D. K.; Iversen, P. L.; Bavari, S. (2010). "Advanced antisense therapies for postexposure protection against lethal filovirus infections". Nature Medicine. 16 (9): 991–994. doi:10.1038/nm.2202. PMID 20729866. S2CID 205387144.

- ↑ "Sarepta Therapeutics Announces Positive Safety Results from Phase I Clinical Study of Marburg Drug Candidate - Business Wire". 2014-02-10. Archived from the original on 2018-08-22. Retrieved 12 October 2014.

- ↑ "Successful Marburg Virus Treatment Offers Hope for Ebola Patients". National Geographic. 2014-08-20. Archived from the original on 2018-08-22. Retrieved 12 October 2014.

- ↑ Martini, G. A.; Schmidt, H. A. (1968). "Spermatogenic transmission of the "Marburg virus". (Causes of "Marburg simian disease")". Klinische Wochenschrift. 46 (7): 398–400. doi:10.1007/bf01734141. PMID 4971902. S2CID 25002057.

- ↑ Siegert, R.; Shu, H. -L.; Slenczka, W. (2009). "Nachweis des "Marburg-Virus" beim Patienten". Deutsche Medizinische Wochenschrift. 93 (12): 616–619. doi:10.1055/s-0028-1105105. PMID 4966286.

- ↑ Kuming, B. S.; Kokoris, N. (1977). "Uveal involvement in Marburg virus disease". The British Journal of Ophthalmology. 61 (4): 265–266. doi:10.1136/bjo.61.4.265. PMC 1042937. PMID 557985.

- ↑ "Known Cases and Outbreaks of Marburg Hemorrhagic Fever, in Chronological Order". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. July 31, 2009. Archived from the original on 20 September 2011. Retrieved 2 September 2011.

- ↑ "Marburg haemorrhagic fever". Health Topics A to Z. Archived from the original on 2016-10-16. Retrieved 2011-09-25.

- ↑ "Outbreak Table | Marburg Hemorrhagic Fever | CDC". www.cdc.gov. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Archived from the original on 21 January 2015. Retrieved 4 August 2018.

- ↑ "WHO | Marburg haemorrhagic fever in Uganda". www.who.int. Archived from the original on 8 October 2014. Retrieved 23 October 2017.

- ↑ "Imported Case of Marburg Hemorrhagic Fever --- Colorado, 2008". cdc.gov. Archived from the original on 23 May 2017. Retrieved 23 October 2017.

- ↑ "Marburg hemorrhagic fever outbreak continues in Uganda". October 2012. Archived from the original on 2018-06-12. Retrieved 2014-10-08.

- ↑ "WHO | Marburg haemorrhagic fever in Uganda – update". www.who.int. Archived from the original on 10 August 2014. Retrieved 29 October 2017.

- ↑ "1st LD-Writethru: Deadly Marburg hemorrhagic fever breaks out in Uganda". October 5, 2014. Archived from the original on December 5, 2017. Retrieved October 8, 2014.

- ↑ "WHO | Marburg virus disease – Uganda". www.who.int. Archived from the original on 17 November 2014. Retrieved 29 October 2017.

- ↑ News, ABC. "Uganda controls deadly Marburg fever outbreak, WHO says". ABC News. Archived from the original on 8 December 2017. Retrieved 8 December 2017.

- ↑ Kissling, R. E.; Robinson, R. Q.; Murphy, F. A.; Whitfield, S. G. (1968). "Agent of disease contracted from green monkeys". Science. 160 (830): 888–890. Bibcode:1968Sci...160..888K. doi:10.1126/science.160.3830.888. PMID 4296724. S2CID 30252321.

- ↑ Bonin, O. (1969). "The Cercopithecus monkey disease in Marburg and Frankfurt (Main), 1967". Acta Zoologica et Pathologica Antverpiensia. 48: 319–331. PMID 5005859.

- ↑ Jacob, H.; Solcher, H. (1968). "An infectious disease transmitted by Cercopithecus aethiops ("marbury disease") with glial nodule encephalitis". Acta Neuropathologica. 11 (1): 29–44. doi:10.1007/bf00692793. PMID 5748997. S2CID 12791113.

- ↑ Stojkovic, L.; Bordjoski, M.; Gligic, A.; Stefanovic, Z. (1971). "Two Cases of Cercopithecus-Monkeys-Associated Haemorrhagic Fever". In Martini, G. A.; Siegert, R. (eds.). Marburg Virus Disease. Berlin, Germany: Springer-Verlag. pp. 24–33. ISBN 978-0-387-05199-4{{inconsistent citations}}

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: postscript (link) - ↑ Garrett, Laurie (1994). The Coming Plague: Newly Emerging Diseases in a World Out of Balance. New York, USA: Farrar, Straus & Giroux. ISBN 978-0-374-12646-9.

- ↑ Gear, J. H. (1977). "Haemorrhagic fevers of Africa: An account of two recent outbreaks". Journal of the South African Veterinary Association. 48 (1): 5–8. PMID 406394.

- ↑ Conrad, J. L.; Isaacson, M.; Smith, E. B.; Wulff, H.; Crees, M.; Geldenhuys, P.; Johnston, J. (1978). "Epidemiologic investigation of Marburg virus disease, Southern Africa, 1975". The American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. 27 (6): 1210–1215. doi:10.4269/ajtmh.1978.27.1210. PMID 569445.

- ↑ Smith, D. H.; Johnson, B. K.; Isaacson, M.; Swanapoel, R.; Johnson, K. M.; Killey, M.; Bagshawe, A.; Siongok, T.; Keruga, W. K. (1982). "Marburg-virus disease in Kenya". Lancet. 1 (8276): 816–820. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(82)91871-2. PMID 6122054. S2CID 42832324.

- ↑ 81.0 81.1 Preston, Richard (1994). The Hot Zone – A Terrifying New Story. New York, USA: Random House. ISBN 978-0-385-47956-1.

- ↑ Beer, B.; Kurth, R.; Bukreyev, A. (1999). "Characteristics of Filoviridae: Marburg and Ebola viruses". Die Naturwissenschaften. 86 (1): 8–17. Bibcode:1999NW.....86....8B. doi:10.1007/s001140050562. PMID 10024977. S2CID 25789824.

- ↑ Alibek, Ken; Handelman, Steven (1999). Biohazard: The Chilling True Story of the Largest Covert Biological Weapons Program in the World—Told from Inside by the Man Who Ran It. New York, USA: Random House. ISBN 978-0-385-33496-9{{inconsistent citations}}

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: postscript (link) - ↑ Bertherat, E.; Talarmin, A.; Zeller, H. (1999). "Democratic Republic of the Congo: Between civil war and the Marburg virus. International Committee of Technical and Scientific Coordination of the Durba Epidemic". Médecine Tropicale: Revue du Corps de Santé Colonial. 59 (2): 201–204. PMID 10546197.

- ↑ Bausch, D. G.; Borchert, M.; Grein, T.; Roth, C.; Swanepoel, R.; Libande, M. L.; Talarmin, A.; Bertherat, E.; Muyembe-Tamfum, J. J.; Tugume, B.; Colebunders, R.; Kondé, K. M.; Pirad, P.; Olinda, L. L.; Rodier, G. R.; Campbell, P.; Tomori, O.; Ksiazek, T. G.; Rollin, P. E. (2003). "Risk Factors for Marburg Hemorrhagic Fever, Democratic Republic of the Congo". Emerging Infectious Diseases. 9 (12): 1531–1537. doi:10.3201/eid0912.030355. PMC 3034318. PMID 14720391.

- ↑ Hovette, P. (2005). "Epidemic of Marburg hemorrhagic fever in Angola". Médecine Tropicale: Revue du Corps de Santé Colonial. 65 (2): 127–128. PMID 16038348.

- ↑ Ndayimirije, N.; Kindhauser, M. K. (2005). "Marburg Hemorrhagic Fever in Angola—Fighting Fear and a Lethal Pathogen". New England Journal of Medicine. 352 (21): 2155–2157. doi:10.1056/NEJMp058115. PMID 15917379.

- ↑ Towner, J. S.; Khristova, M. L.; Sealy, T. K.; Vincent, M. J.; Erickson, B. R.; Bawiec, D. A.; Hartman, A. L.; Comer, J. A.; Zaki, S. R.; Ströher, U.; Gomes Da Silva, F.; Del Castillo, F.; Rollin, P. E.; Ksiazek, T. G.; Nichol, S. T. (2006). "Marburgvirus Genomics and Association with a Large Hemorrhagic Fever Outbreak in Angola". Journal of Virology. 80 (13): 6497–6516. doi:10.1128/JVI.00069-06. PMC 1488971. PMID 16775337.

- ↑ Jeffs, B.; Roddy, P.; Weatherill, D.; De La Rosa, O.; Dorion, C.; Iscla, M.; Grovas, I.; Palma, P. P.; Villa, L.; Bernal, O.; Rodriguez-Martinez, J.; Barcelo, B.; Pou, D.; Borchert, M. (2007). "The Médecins Sans Frontières Intervention in the Marburg Hemorrhagic Fever Epidemic, Uige, Angola, 2005. I. Lessons Learned in the Hospital" (PDF). The Journal of Infectious Diseases. 196: S154–S161. doi:10.1086/520548. PMID 17940944. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2017-08-12. Retrieved 2018-04-20.

- ↑ Roddy, P.; Weatherill, D.; Jeffs, B.; Abaakouk, Z.; Dorion, C.; Rodriguez-Martinez, J.; Palma, P. P.; De La Rosa, O.; Villa, L.; Grovas, I.; Borchert, M. (2007). "The Médecins Sans Frontières Intervention in the Marburg Hemorrhagic Fever Epidemic, Uige, Angola, 2005. II. Lessons Learned in the Community" (PDF). The Journal of Infectious Diseases. 196: S162–S167. doi:10.1086/520544. PMID 17940945. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2017-08-09. Retrieved 2018-05-18.

- ↑ Roddy, P.; Marchiol, A.; Jeffs, B.; Palma, P. P.; Bernal, O.; De La Rosa, O.; Borchert, M. (2009). "Decreased peripheral health service utilisation during an outbreak of Marburg haemorrhagic fever, Uíge, Angola, 2005" (PDF). Transactions of the Royal Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. 103 (2): 200–202. doi:10.1016/j.trstmh.2008.09.001. hdl:10144/41786. PMID 18838150. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2017-08-09. Retrieved 2018-04-29.

- ↑ Adjemian, J.; Farnon, E. C.; Tschioko, F.; Wamala, J. F.; Byaruhanga, E.; Bwire, G. S.; Kansiime, E.; Kagirita, A.; Ahimbisibwe, S.; Katunguka, F.; Jeffs, B.; Lutwama, J. J.; Downing, R.; Tappero, J. W.; Formenty, P.; Amman, B.; Manning, C.; Towner, J.; Nichol, S. T.; Rollin, P. E. (2011). "Outbreak of Marburg Hemorrhagic Fever Among Miners in Kamwenge and Ibanda Districts, Uganda, 2007". Journal of Infectious Diseases. 204 (Suppl 3): S796–S799. doi:10.1093/infdis/jir312. PMC 3203392. PMID 21987753.

- ↑ Timen, A.; Koopmans, M. P.; Vossen, A. C.; Van Doornum, G. J.; Günther, S.; Van Den Berkmortel, F.; Verduin, K. M.; Dittrich, S.; Emmerich, P.; Osterhaus, A. D. M. E.; Van Dissel, J. T.; Coutinho, R. A. (2009). "Response to Imported Case of Marburg Hemorrhagic Fever, the Netherlands". Emerging Infectious Diseases. 15 (8): 1171–1175. doi:10.3201/eid1508.090015. PMC 2815969. PMID 19751577.

- ↑ Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) (2009). "Imported case of Marburg hemorrhagic fever - Colorado, 2008". MMWR. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 58 (49): 1377–1381. PMID 20019654.

- ↑ "Marburg virus disease – Uganda and Kenya". WHO. 7 November 2017. Archived from the original on 2017-11-09. Retrieved 2017-12-04.

- ↑ Dana Dovey (18 November 2017). "WHAT IS MARBURG? THIS VIRUS CAUSES VICTIMS TO BLEED FROM EVERY ORIFICE AND DIE". Newsweek. Archived from the original on 2018-07-04. Retrieved 2017-12-04.

External links[edit | edit source]

- ViralZone: Marburg virus Archived 2009-05-04 at the Wayback Machine

- Centers for Disease Control, Infection Control for Viral Haemorrhagic Fevers In the African Health Care Setting.

- Center for Disease Control, Marburg Haemorrhagic Fever.

- Center for Disease Control, Known Cases and Outbreaks of Marburg Haemorrhagic Fever

- Ebola and Marburg haemorrhagic fever (10 July 2008) factsheet from European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control

- World Health Organization, Marburg Haemorrhagic Fever Archived 2020-05-02 at the Wayback Machine.

- Red Cross PDF Archived 2020-09-23 at the Wayback Machine

- Virus Pathogen Database and Analysis Resource (ViPR): Filoviridae

| Classification | |

|---|---|

| External resources |

Categories: [Animal viral diseases] [Animal virology] [Arthropod-borne viral fevers and viral haemorrhagic fevers] [Biological weapons] [Hemorrhagic fevers] [Tropical diseases] [Virus-related cutaneous conditions] [Zoonoses] [Marburgviruses] [RTT]

↧ Download as ZWI file | Last modified: 02/16/2024 04:07:36 | 2 views

☰ Source: https://mdwiki.org/wiki/Marburg_virus_disease | License: CC BY-SA 3.0

KSF

KSF