World History Lecture Twelve

From Conservapedia

From Conservapedia 1-2-3-4-5-6-7-8-9-10-11-12-13-14

This lecture focuses on World War II: before, during and after. No war in the history of the world (except, perhaps, the American Revolutionary War) had as much lasting impact as World War II. We still feel some of its effects to this day, about 70 years later. The negotiations at the end of the war, which allowed the communist Soviet Union to gain control over several nations in Eastern Europe, resulted in the denial of freedom to many millions of people for 40 years.

Contents

The Rise of Fascism in Europe[edit]

The world in the 1930s was suffering from the Great Depression. This created discontent and encouraged change. National governments were in place in Italy and Germany, but the people were not happy with them.

Nationalism had been developing for decades, but it turned into an extreme form known as “fascism” during this period. Fascism is defined as a political philosophy that elevates the nation and its ethnicity above the individual, and uses a dictator to impose economic and social regimentation. Often symbols are used for the purpose of mind-control, like the swastika in Germany. Special salutes are also required to inculcate complete devotion to the national ruler, such as "Heil Hitler." Mass rallies were common. All opposition was suppressed.

Fascism is very different from communism, and fascist countries were the mortal enemies of communist countries. Communism sought a worldwide revolution that would abolish national identity, while fascism sought to advance one's nation over the rest of the world. Communism opposed different social classes, while fascism encouraged this. Communism hated wealth, while fascism encouraged the creation of wealth to make the nation stronger. Communism considered everyone to be equal, while fascists thought their nation was the best. Communism pushed women into the traditionally male roles of industrial workers and even soldiers, while strongly nationalistic countries like Japan imported foreign male workers from Korea and China rather than force women into industrial jobs. Many observe that fascism and communism are opposites, but they did have a few key characteristics in common: both used a dictator and demanded complete allegiance to the state ruler, rather than to God. Both also had a disdain for individual freedom and human rights, and both stressed the collective.

Mussolini[edit]

The first signs of fascism were in Italy, where the people were upset at not acquiring territory as a result of World War I, and where economic problems existed earlier than the Great Depression. In 1919, Benito Mussolini founded Italy’s Fascist Party, emphasizing the need to improve Italy’s economy and its military. In October 1922, the Fascists or “Black Shirts” protested in Rome, causing King Victor Emmanuel to make Mussolini the leader of Italy (“Il Duce”). Mussolini then suppressed all opposition. Ironically, Mussolini forbade strikes as he wanted to win over the wealthy people in the country and build Italy’s economic strength.

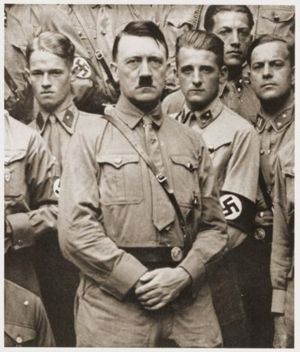

Hitler and the Nazis[edit]

In Germany the name of the fascists was the “Storm Troopers” or “Brownshirts”, and their political party was called Nationalsozialismus, the Nationalist Socialist German Workers’ Party, or “Nazis” for short. Adolf Hitler became their leader and he promised to stop communism and undo the Treaty of Versailles, which many Germans considered to be a humiliation to their nation. (The resentment caused by this treaty is often cited as a reason for Hitler's rise to power.) In 1923 Hitler led an armed rebellion in Munich, but was defeated and jailed. While imprisoned, he wrote Mein Kampf (My Struggle) in which he declared “Aryans” to be the master race. Adolf Hitler was an evolutionary racist. Hitler considered most German people to be “Aryans”, a term that properly refers to the Indo-European people who partly migrated to India. The connection is ironic because the swastika, Hitler’s symbol, is borrowed from Hinduism and the name itself is Sanskrit. But when Hitler said “Aryan” he meant people having Nordic features rather Indian features.

Hitler also promised to help Germany take back land it lost in the Treaty of Versailles and to conquer Russia and Eastern Europe so that Germans could have more living space, or “lebensraum”.

In 1933, Germany was in the throes of the Great Depression and German President Paul von Hindenburg panicked by naming Hitler chancellor. This was one of the biggest mistakes in world history. Hitler quickly solidified power for the Nazis. Calling himself Der Fuhrer, Hitler began in 1934 to murder hundreds of Germans who had opposed him. Hitler developed a secret police known as the Gestapo, and also a special, black-uniformed public police known as the Schutzstaffel, or SS. Hitler took over the schools, requiring teenagers to join the Hitlerjugend, or Hitler Youth (for boys) and the League of German Girls (for girls). They were then brainwashed with pro-Hitler propaganda. But Hitler promoted industrialization and revived the economy, making him a hero in Germany and even to some in the United States.

From the start Hitler blamed Jewish people in Germany for its problems. In 1933, the Nazis began passing laws taking away rights from Jews, and on Nov. 9, 1938 the Nazis conducted a massive pogrom in a thousand German towns that attacked Jewish people in their homes and destroyed their businesses. That day, which came after years of harassment, is known as the “Kristallnacht”, or the night of broken glass. Afterward Jews were prohibited from being in public buildings or owning or working in retail stores.

Time magazine named Hitler "Man of the Year" at the end of 1938. It explained that the:[1]

- Greatest single news event of 1938 took place on September 29, when four statesmen met at the Führerhaus, in Munich, to redraw the map of Europe. The three visiting statesmen at that historic conference were Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain of Great Britain, Premier Edouard Daladier of France, and Dictator Benito Mussolini of Italy. But by all odds the dominating figure at Munich was the German host, Adolf Hitler.

- Führer of the German people, Commander-in-Chief of the German Army, Navy & Air Force, Chancellor of the Third Reich, Herr Hitler reaped on that day at Munich the harvest of an audacious, defiant, ruthless foreign policy he had pursued for five and a half years. He had torn the Treaty of Versailles to shreds. He had rearmed Germany to the teeth — or as close to the teeth as he was able. He had stolen Austria before the eyes of a horrified and apparently impotent world.

Franco and the Spanish civil war[edit]

Meanwhile, dictators were rising to power in other countries. In 1936, a civil war broke out in Spain when fascists who supported General Francisco Franco attempted to overthrow the elected republican government. This was a three-sided civil war, as Franco’s Nationalists battled a group of communists (the “International Brigades”) as well as the Republicans, and it lasted for three bloody years until 1939. This war attracted attention by writers and thinkers worldwide. The British writer George Orwell, who later penned classic anti-communist novels entitled Animal Farm and 1984, volunteered to fight against both the communists and Franco’s fascists. Orwell survived after taking a bullet through his neck.[2] Britain, France and the United States remained officially neutral while Germany and Italy helped Franco. Some Americans felt that Franco was far better than the communists, and were relieved that Franco won.

Yugoslavia, Poland, Romania, Hungary, Bulgaria and Albania were also taken over by their own dictators. The only democracy left in Eastern Europe in 1935 was Czechoslovakia.

World War II[edit]

Two nations – Germany and Japan – had built themselves into perfect fighting machines. They lacked diversity in their populations, with the German people being almost completely of one Germanic ethnicity, and the Japanese population being almost completely of one Japanese ethnicity. Both nations had become dominated by non-Christian belief systems. In Germany the prevailing view among the elite was that there was, or should be, a master race that defeats all others. In Japan, there was unyielding devotion to their warlord emperor, whom they believed to be a god.

Both countries had powerful industrial economies to feed their thirst for power. In Germany, a leader (Adolf Hitler) had risen to power who had phenomenal public speaking skills, and who could whip the German people into a frenzy with his demagoguery. In Japan the national religion (Shinto) called on the Japanese to do the emperor’s will as though a god had ordered them to do so.

Germany and Japan each experienced a rise of nationalism and the rise of an influential, popular dictator, and began to threaten the world at the same time. Other nations experienced the same rise of nationalism, and dictators coming to power, but did not become as serious of a threat. Why was it that these two nations independently arrived at similar nationalism and dictatorship, but came from very different starting points. Just as we saw unrelated peoples do similar things in ancient times, such as building structures that looked like ziggurats, and in medieval times, such as the development of feudalism in both Europe and Japan, there was the odd coincidence of German and Japan nationalism independently threatening the world at the same time.

Aggression in the 1930s[edit]

Japan’s feudal period had militaristic aspects, but by the 1920s Japan was a democratic government that signed the Kellogg-Briand Pact for peace. Then the Great Depression hit Japan just like everywhere else, and the Japanese overthrew their democratic government and replaced it with a military regime. Emperor Hirohito rose to power as a military ruler.

Japan decided that it could solve its economic problems by expanding. That would enable it to obtain raw materials for production and new markets for exports. At least that is what many historians say. Perhaps the real truth is that the Japanese liked winning wars and no one had beaten them yet. China was many times bigger than Japan, but was no match for the Japanese military. Japan invaded Manchuria in 1931, attracted in part by the coal and iron deposits there. This invasion began the Asian phase of World War II.

The League of Nations condemned this invasion but chose not to stop it, for fear that any opposition would spark another war like the one they had just suffered through. They held onto the hope that if left alone, the invasions would stop. Japan withdrew from the League in 1933, and, along with Germany, played off of the fears of the League of Nations.

In 1937, Japan invaded northern and central China. It sacked the Chinese capital of Nanjing, killing thousands of soldiers and civilians. Jiang Jieshi fled to the west while both nationalist and communist Chinese fighters stayed to combat the Japanese.

In a completely unrelated move, Italy invaded one of the last remaining independent nations in Africa: Ethiopia. In the 1890s, Ethiopia had fought off the Italians, but Mussolini was back for revenge. He easily conquered Ethiopia in 1935-1936 and, again, the League of Nations could do nothing when Ethiopian Emperor Haile Selassie begged for help.

By 1935 Hitler was rearming Germany, and in 1936 he moved German troops into the buffer zone separating Germany from France: the industrialized Rhineland. This violated the Treaty of Versailles but no one did anything to stop it, including the powerless League of Nations. Mussolini thought it best to ally Italy with Germany, and in October 1936 they formed the Rome-Berlin Axis. Japan allied with Germany the following month, and the unified Germany-Italy-Japan Axis Powers formed in 1937. In 1940, Italy, Germany, and Japan solidified the Axis Powers in the Tripartite Pact.

Hitler was just warming up. Next he wanted to annex Austria to Germany, as they had been combined in the past. Hitler himself was born in Austria and many Austrians supported joining Germany. So Hitler annexed Austria on March 12, 1938 without much resistance, and this is known as the Anschluss (unification of Austria and Germany). France and Britain had promised to defend the independence of Austria, but did nothing.

The more Hitler grabbed, the more he wanted. He turned to western Czechoslovakia, which had a large number of German speakers. In September 1938 he demanded that this region, the Sudetenland, submit to Germany and join it. But the Czech government refused and turned to France for assistance.

Mussolini called for the Munich Conference in September 1938 to address this crisis about Czechoslovakia. Germany, Italy, Britain and France were invited, while Stalin’s Soviet Union and Czechoslovakia were not. In a classic example of making a deal with the devil, Britain and France agreed to allow Hitler to take the Sudetenland in exchange for his promise to stop there and not invade Czechoslovakia further. British Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain, in one of the worst blunders in the history of the world, insisted that appeasing Hitler was the best approach. Chamberlain received a hero’s welcome on his return to England, and he declared that he had achieved “peace in our time.” An English newspaper justified the appeasement by claiming that Germans were simply “going into their own back yard.” But within six months, Hitler annexed all of Czechoslovakia and then Mussolini grabbed Albania. Chamberlain was discredited, and his major critic (the more conservative Winston Churchill) replaced him in 1940.

Hitler was now ready to make his big move. He demanded that Poland give back a former German seaport known as Danzig. Poland refused and prepared to defend against a German invasion. Courageous Polish soldiers on horses defended against German tanks! Poland obtained the support of Britain and France, who promised to help Poland defend if Germany attacked. Britain and France then turned to Stalin in the Soviet Union, but he double-crossed them. Stalin secretly agreed with Hitler in August 1939 to divide Poland among themselves and not to attack each other. Stalin also received a promise from Hitler that Stalin could annex Lithuania, Estonia, Latvia and Finland.

German Aggression in 1939-1940[edit]

Hitler’s dictatorship, the Third Reich, was ready to begin conquering all of Europe. He started with Poland based on Stalin’s promise not to interfere. On September 1, 1939, Hitler launched a lightning-fast, massive attack (a “blitzkrieg”) against Poland. A blitzkrieg combines bombing with a tank invasion. As mentioned above, Polish soldiers fought valiantly on horseback, but were crushed. France and Britain declared war on Germany in two days, on September 3rd. After destroying Warsaw, Poland, with the bombing and destruction of the Polish militia, Hitler annexed western Poland to Germany.

By mid-September, Stalin was grabbing eastern Poland and also annexing Lithuania, Estonia and Latvia. Finland put up an awesome struggle against Stalin, and the typically cold winter helped its defenses. But by March 1940, the massive Soviet army had taken some territory from Finland.

Germany did little for six months after taking Poland. The Germans nicknamed this the “Sitzkrieg” ("sit" – zkrieg). Even though war had been declared, the nations seemed to be watching and waiting. Some call this period the “phony war.” The French fortified the Maginot Line, which was a defensive line set up along the French-German border. Ever since World War I, the French relied on a strong line there to prevent Germans from ever invading again. But Germany later invaded by going around (“outflanking”) the Maginot Line.

The Germans, meanwhile, fortified their Siegfried Line on their side. Then, on April 9, 1940, the Germans invaded Denmark and Norway. Denmark surrendered quickly, and by June Norway had fallen also.

By the middle of 1940 a real world war had begun again. On one side were the Axis Powers of Japan, Germany and Italy. On the other side where the Allied Powers of Great Britain and its colonies (commonwealth), the nations of Australia, Canada and New Zealand, France and its colonies, and potentially the United States and the Soviet Union.

Hitler Takes Continental Europe[edit]

After taking Norway and Denmark, Hitler invaded and quickly conquered the Netherlands, Belgium and Luxembourg. The Allies were out-manned and ill-equipped for the German tanks and air force. The Allies retreated to Dunkirk, a harbor town on the northernmost tip of France, across the English Channel from England. There they expected to be slaughtered by the advancing German forces.

The Germans did bomb the Allies mercilessly at Dunkirk. But in what Winston Churchill called the “miracle of Dunkirk,” 338,226 soldiers were evacuated to England during constant bombing. This required over 900 vessels to cross the English Channel, and the abandonment of 40,000 land vehicles at Dunkirk. The code name for this was Operation Dynamo. Towards the end of the war, the Allied forces would return to liberate this town amid heavy German resistance.

France fell to the Axis Powers on June 24, 1940, after Mussolini joined forces with Hitler and invaded France from the south. The Germans took control of northern France, and in Southern France the Germans installed a Nazi-controlled government (the Vichy government) under a “puppet” for the Germans, French Prime Minister Henri Petain. The real French government, led by French general Charles de Gaulle, was set up as government-in-exile in London. De Gaulle’s Free French armies continued to battle Germany until the Allied Forces liberated France in 1944.

After France fell, the only remaining prize in Europe for the Germans to capture was Great Britain itself. (Switzerland, a small country protected by the Alps and a tremendous self-defense system that included gun ownership by nearly every family, was never invaded by the Germans.)

Great Britain’s new leader, Winston Churchill, refused to surrender to Hitler. Hitler began Operation Eagle to bomb London, using the powerful German air force (the Luftwaffe). From September 1940 to May 1941, “the Blitz” consisted of constant German bombing of British cities, especially London. There were more than 40,000 civilian casualties, and people would listen for air sirens as the signal to hide in underground shelters.

A new invention, radar, saved the British. The British Royal Air Force (RAF) began tracking incoming German airplanes and started shooting them down. Also, the will of the British to survive deprived the bombing campaign of victory. Hitler was forced to suspend the bombing in May 1941, and the Battle of Britain was over.

Recall that Hitler was anti-communist, and even though he had a secret agreement with Stalin over Poland, Hitler long planned to defeat Stalin. He prepared to accomplish this by first conquering the Balkans in 1940, thereby persuading Romania, Hungary and Bulgaria to join the Axis Powers. When two countries refused to submit (Yugoslavia and Greece), Hitler simply invaded and conquered them in 1941.

Hitler was then ready to invade the Soviet Union, beginning on June 22, 1941 in Operation Barbarossa. The irresistible force had met the immovable object, as the Soviet Union had the largest and most vicious army in the world. The communists lacked the technology of the Germans, but the Soviet Union had more people and just as much industrial capacity. This invasion by Hitler caused the Soviet Union to join the Allied Powers.

Still, the Germans pushed the Soviets back, and the communists resorted to their “scorched-earth” policy of burning everything in sight as they retreated. A similar policy had been used by the Russians to survive Napoleon’s invasion over a century earlier. Then the harsh winter hit the German troops, and 500,000 German soldiers froze to death from the frigid temperatures. Hitler felt he could capture Leningrad, but Russians never surrender and they lived on rats rather than give their city to the Germans. That forced the Germans to remain outside the city, freezing to death. When the Germans proceeded to Moscow in December 1941, Soviet General Georgi Zhukov defeated them with Siberian troops. The Germans paid a heavy price for trying to defeat the Soviet Union.

Meanwhile, one of the shrewdest commanders in world history, the German field general Erwin Rommel, came to the aid of the Italians in northern Africa. In September 1940, Mussolini advanced towards the Suez Canal and the rich oil fields of the Middle East. The British woke up to this and defeated the Italians, capturing more than 100,000 prisoners in the process.

But the brilliant German Rommel, nicknamed “The Desert Fox,” brought a powerful German tank corps known as the Afrika Korps to the aid of the Italians. He crushed the British in Libya, who were then forced to retreat to Tobruk.

The Holocaust and “Final Solution”[edit]

Adolf Hitler blamed the Jewish people for Germany’s troubles. The Nuremburg Laws of 1935 prohibited Jewish people (and other groups) from holding official positions in government.[3] Hitler found it useful for his goals to have a scapegoat, and the Nazis made the Jewish people the scapegoat. Other groups, such as gypsies, also became scapegoats. Nazis claimed to be returning to German tradition by excluding Jews. The Nuremberg Laws also prohibited Jewish people from owning property or even becoming German citizens. Nazis forced Jewish people to wear a bright yellow Star of David on their clothing, as a way of ostracizing them.

Jewish people began to flee Germany, emigrating to other countries such as the United States and safer countries in Europe. But other countries, including the United States, had limits on immigration. The pogrom of the Kristallnacht in 1938, described earlier, increased the Jewish emigration from Germany.

Many Jewish people remained in Germany and throughout Europe, and they became victimized by Hitler’s “Final Solution” (“Endlosung”), which was the “Holocaust”: the systematic execution of Jewish people and other innocent victims in concentration camps. Other groups considered by Hitler to be inferior, such as gypsies and the disabled, were also targeted. In 1941, Hitler began rounding them up and forcing them into segregated communities called ghettos, surrounded by barbed wire. Concentration and extermination camps having gas chambers for mass executions were built to kill Jews. Of the 6 million Jews killed in these camps, 3 million were from Poland, 1.5 million from the Soviet Union, and 160,000 from Germany.[4] It is difficult to understand why no one stopped this massacre until the Allied forces liberated the concentration camps. Five million others, including millions of Christians, were also killed in these concentration camps.[3]

The “Angel of Death” in one of the worst extermination (or death) camps, Auschwitz, was Dr. Josef Mengele. Mengele had obtained a Ph.D. based on Darwinian evolution, and had written his dissertation thesis on racial differences among humans. He supported and reinforced Nazi theories of racial superiority with phony research claims. He was an ardent supporter of “survival of the fittest” and he performed cruel experiments on humans at the concentration camp in furtherance of the theory of evolution. He attempted to prove that disease was the product of racial inferiority, and he would amputate healthy limbs and perform other cruel surgeries on prisoners. Today Mengele is criticized by everyone, but supporters of the theory of evolution omit mentioning how much Mengele’s work was based on that theory. Mengele was never punished for his crimes, and after the war he fled to Brazil, where decades later he drowned after suffering a stroke in his brain, while swimming.

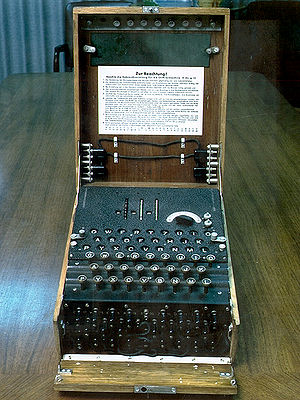

The Enigma[edit]

In warfare, both sides use "ciphers" to encrypt their messages about troop movements and planned attacks in secret codes so that the enemy cannot eavesdrop and understand the communications. The National Security Agency is a super-secret branch of the U.S. Government staffed by mathematicians who seek better ways to protect American communications against enemy interception, and better ways to decode or decrypt the secret messages of the enemy to anticipate their next moves.

As an NSA report explains about World War II:[5]

- Two examples of famous ciphers from World War II are the Axis cipher machines, the German Enigma and the Japanese Purple (known to the Japanese as the 97-shiki O-bun In-ji-ki, or Alphabetical Typewriter ’97). Both machines substituted letters for plaintext elements according to daily settings (key) for each machine. Interestingly, most ciphers used by all sides during the war overwhelmingly were manual in nature. That is, they involved the use of paper charts and key. Such a manual cipher was the double transposition cipher used by German Police units to encrypt their reports about the massacres of Jews, partisans, prisoners, and Soviet commissars to Police headquarters in Berlin.

The Enigma was a portable cipher machine, roughly the size of a typewriter, which could encrypt and decrypt secret messages. It used electro-mechanical rotors to convert a message to a secret code, and then another machine could decode that same message and reveal the original message. This machine was commercially available beginning in the early 1920s. The Nazi German military version generated codes widely thought to be unbreakable.

The Enigma machine was equipped with a 26-letter keyboard, with one light per letter of the alphabet. Inside the machine was a set of wired drums for scrambling the input. To encipher or encrypt a letter, the operator pushed the relevant key and observed which of the lights lit. The communication between two operators required that each had an Enigma machine set up in the same way as each other. The large number of possibilities for setting the rotors (and a plugboard that could swap letters) made for an astronomical number of possible configurations, each producing a different cipher. The Germans changed the settings daily, such that the code had to be re-broken each day in order to decrypt the messages.

For others to break (decrypt) the code, they had to figure out how the Enigma functioned, the wiring of its rotors and its daily settings (both rotors and plugboard).

Nazi Germany used the Enigma before and during World War II to send messages about its military maneuvers. But in 1932 a 27-year-old Polish mathematician (specifically, a cryptologist) named Marian Rejewski used advanced mathematics (permutation theory with some group theory) to secretly break (“crack”) the Enigma codes. He then helped design working “doubles” of the Enigmas that could find the keys necessary for decryption. By 1938 the Poles were decrypting most of the German messages, and the Poles shared their marvelous discovery with Great Britain and France.

This breakthrough enabled the Allies to anticipate German military maneuvers, although sometimes the Allies would allow an attack to occur successfully in order to avoid signaling to the Germans that their code had been broken. The Allied code-breaking effort was known as “Ultra”, as in “ultra-secret”. At the end of the war, Allied General Dwight Eisenhower said that Ultra was “decisive” to the Allied victory over Germany. British Prime Minister Winston Churchill also declared, “It was thanks to Ultra that we won the war.” The breaking of the German codes prevented Germany from completely blockading Britain with U-boats and enabled the Allied forces to make key strategic decisions throughout the war.

America Enters the War[edit]

Throughout the 1930s, there was ambivalence in England and the United States about Hitler and the Nazis. In America many people are of German descent, and Hitler was popular. Time Magazine named him as “Man of the Year.” On some college campuses, Hitler was voted the greatest leader.

Some viewed Hitler as an answer to Joseph Stalin and communism in Russia (although some Americans had supported Stalin and communism). Others thought there was a “Jewish problem” in Europe. G.K. Chesterton, who favored creating a new state like Israel for the Jewish population, said this in 1934: “Today, although I still think there is a Jewish problem, I am appalled by the Hitlerite atrocities. They have absolutely no reason or logic behind them. It is quite obviously the expedient of a man who has been driven to seeking a scapegoat, and has found with relief the most famous scapegoat in European history, the Jewish people.”

But most in America felt it was time to stay out of Europe and let Germany, France, England and Italy solve their own conflicts. No one in America expected the Holocaust, and Hitler kept it quiet even after it began in 1942. In the late 1930s, the debate over involvement by the United States in Europe had almost nothing to do with discrimination against Jewish people by the Nazis. Discrimination based on race was common throughout the world, and the United States herself had many laws or policies discriminating based on race.

In an effort to remain neutral, Congress passed several laws between 1935 and 1937 making it illegal for Americans to lend money to a nation at war, or sell it weapons. But by 1941, President Roosevelt felt he needed to help England, and he persuaded Congress to pass the Lend-Lease Act to allow him to lend or lease weapons to any nation that he considered to be vital to the United States. As a practical matter, this meant that President Roosevelt could now help England. President Roosevelt ordered the U.S. Navy to begin escorting British ships that carried American arms, and Hitler predictably responded by commanding his U-boats (submarines) to sink cargo ships. When a U-boat shot torpedoes at a U.S. destroyer in the Atlantic in September 1941, President Roosevelt ordered the U.S. ships to fire back. An unofficial war had begun between the United States and Germany.

President Roosevelt met secretly with Winston Churchill, the Prime Minister of Great Britain, in August 1941 on a boat in the Atlantic. Roosevelt and Churchill agreed on a declaration for free trade and self-determination, disarmament of aggressor states (e.g., Japan and Germany) and freedom of the seas. This became known as the Atlantic Charter. The United States and Great Britain renounced any territorial ambitions, and expansion against the wishes of local populations was condemned. The Soviet Union soon endorsed the Atlantic Charter and the Charter later provided the ideological foundation for the United Nations.

By late 1941 President Roosevelt wanted the United States in the war, primarily to save England but also to avert attention from his failure to end the Great Depression. But the American people were not in favor of another world war. Many prominent Americans, such as Charles Lindbergh, opposed American involvement in this war. Many felt that the communist threat to the world was greater than the Nazi threat. Roosevelt needed a way to turn public opinion in favor of war, and generate enough public support to win the war.

The Japanese did the trick. On Dec. 7, 1941, the “day that will live in infamy,” the Japanese launched a surprise attack on our navy fleet at Pearl Harbor in Hawaii, which was not yet a state. Some people believe that Roosevelt knew the Japanese would attack because American mathematicians had broken the Japanese code and intercepted and decoded the messages between Japanese officers. Also, the United States had a good radar system that should have been able to predict the attack an hour before it happened. The result of the attack at Pearl Harbor, which sunk much of the U.S. Pacific fleet and killed 2,400 sailors, was complete outrage by the American public against the Japanese. Congress declared war on Japan the next day, and then declared war on Germany (after Germany declared war on the U.S.). America thereby entered World War II.

By this time Japan had already taken over Manchuria in China and established a Japanese state there called Manchukuo. The Japanese viciously exploited and killed thousands of helpless Chinese in the “Rape of Nanjing.” Japan sought to establish a Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere, which was to be an Asia dominated by Japan and lacking in any western influence. Japan had also seized French Indochina (Southeast Asia, primarily Vietnam and Cambodia) in July 1941. Roosevelt had already suspended oil shipments to Japan, and blockaded Japan before it attacked Pearl Harbor. Japan’s attack was perhaps due to this blockade.

But Japan did not stop with its success at Pearl Harbor. It captured Wake Island and Guam in the Pacific, and then invaded the Philippines. General Douglas MacArthur was stationed on the Philippines at the time, and American and Filipino soldiers fought valiantly on the Bataan Peninsula to defend the island against the Japanese. General MacArthur escaped on a small speedboat, and the Japanese conquered the islands, including the island of Corregidor. From there the Japanese also conquered Hong Kong, Singapore, Malaya, the Dutch East Indies, Burma and the Burma Road. The Japanese seemed unstoppable.

It became clear that, for the first time in world history, air power would be decisive in battle. A college dropout named Colonel William "Billy" Mitchell had predicted this in the early 1920s, based in part on his personal experience in leading a large bombing attack on St. Mihiel near the end of World War I. Mitchell announced in the 1920s that Japan would attack us with aircraft and he felt American generals were incompetent and even treasonous in not guarding against this. In 1921 and 1923, Mitchell proved his point by personally flying over and bombing old American and captured German battleships to sink them easily.

In September 1925 a military airship crashed and killed many on board. Mitchell published a diatribe harshly criticizing his superiors, even accusing them of treason in ignoring the need for good military aviation. He was swiftly brought before a military court, known as a court-martial, for insubordination. He was tried for seven weeks, and convicted by a divided jury. One juror, widely thought to be the future General Douglas MacArthur, voted for acquittal. Mitchell was sentenced to a humiliating loss of rank and pay, and he quit. Only after he died and after World War II did President Truman honor him again.

But perhaps Billy Mitchell’s warnings did make a difference. In 1942 the United States sent Lieutenant Colonel James Doolittle to bomb Tokyo and other Japanese cities, largely for symbolic purposes. In May 1942, a fleet of American and Australian ships intercepted a Japanese strike force and stopped Japanese advances at the Battle of Coral Sea. This was the first naval battle in world history in which the opposing ships never saw either other; aircraft based on aircraft carriers flew and attacked each other and the ships.

In June 1942, the Japanese brought together the largest naval force in the world near Midway Island in the Pacific. The American cryptographers had by this time deciphered enough of the Japanese messages to know that there was going to be an attack on Midway, and they knew roughly when the attack would occur. When the Japanese did attack, there was an American force waiting for them. On a reconnaissance mission an alert American pilot with superb eyesight spotted the Japanese fleet on the distant horizon. That gave the Americans the advantage of surprise, as the Japanese were not expecting the Americans to be ready. General Douglas MacArthur, commander of the Allied land forces in the Pacific, then embarked on a strategy of island-hopping to capture strategic islands surrounding Japanese positions. The Japanese, who were trained not to surrender, fought tenaciously for months before succumbing to American and Australian forces in the Battle of Guadalcanal in the Solomon Islands.

The Allies began to win victories against the Axis Powers in Europe. In late 1942, the Allies won the Battle of El Alamein, and with the help of Americans in May 1943 General Dwight Eisenhower led the Allies to a victory against the feared Afrika Korps. Russia continued to hold its own in Stalingrad against the German army.

From northern Africa the Allies were able to invade Sicily in southern Italy, and oust Mussolini from power. The Germans restored him to power, but on June 4, 1944 the Allies broke through to Rome and by April 1945 the Germans were evacuating Italy. Mussolini was then found hiding in a truck. He was promptly shot and hung in a public square in Milan.

American Issues – Korematsu and the Manhattan Project[edit]

In the United States there were some American citizens of Japanese descent, particularly in California. After the attack on Pearl Harbor, fear and distrust about Japanese Americans arose. Rumors of surprise Japanese attacks on the west coast of the United States became common, and some American officials feared spying by Japanese Americans. The loyalty of American citizens of Japanese descent was doubted.

President Roosevelt, with the support of California Governor Earl Warren (who was later appointed Chief Justice of the Supreme Court in the 1950s), ordered that Americans of Japanese descent be forced to live in internment camps where they could be watched 24 hours a day. These included American citizens who had been born in the United States (the “Nisei”). Their property was confiscated also. Many of the internment camps were located away from the coasts in unfamiliar territories, such as near Indian reservations. Overall, 110,000 Japanese Americans were forcibly moved to internment camps during the war.

This policy constituted racial discrimination and some of the victims sued to stop it. But the U.S. Supreme Court upheld this racial discrimination in Korematsu v. United States (1944). Three dissented from this decision, which is considered one of the Court’s most embarrassing rulings. In 1948 Congress enacted the Japanese American Evacuation Claims Act to compensate some of the victims for losing their homes and businesses. In 1980, Congress held hearings to review some of the personal hardships, and issued a report in 1983 condemning President Roosevelt’s removal order and the Supreme Court decision. But many Americans see nothing wrong with taking such measures in a time of crisis and war.

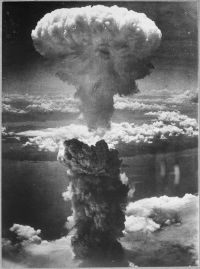

Beginning the day before the attack on Pearl Harbor, American scientists were worked on building an atomic bomb to help end the war. The code name for this project was the “Manhattan Project.”

Since 1900 scientists had known that the natural decay of radioactive elements produced large quantities of energy, much larger than the energy produced by chemical reactions. In 1914, a science-fiction writer named H.G. Wells described futuristic “atomic bombs” in a novel. In 1933, Hungarian-born physicist Leo Szilard had the idea that a nuclear chain reaction could make the rapid release of energy from the atom possible. Japan and Germany had projects to build a bomb too.

Szilard immigrated to the United States and was determined to persuade President Roosevelt to fund the building of an atomic bomb. Szilard felt that a letter to the President by Albert Einstein would help. Einstein, a pacifist, was known better than most physicists. Einstein agreed to sign a letter written by Szilard, which was then taken to President Roosevelt in early August 1939. The letter explained the feasibility and importance of developing an atomic bomb.

But President Roosevelt did little based on this letter, and instead allocated only a tiny $6,000 for such a project. Over two years passed, and no progress was made. It was not until Dec. 6, 1941, the day before Pearl Harbor, that an all-out effort to build an atomic bomb began under the direction of General Leslie Groves. Building on work performed by the brilliant physicist Enrico Fermi at the University of Chicago, a massive and top-secret team of scientists assembled in Los Alamos, New Mexico, to build an atomic bomb. Managers of this project included J. Robert Oppenheimer, who was later accused of being a communist sympathizer.

The scientists eventually succeeded, and rushed a few prototype bombs to the military for potential use near the end of the war in 1945. By then, Americans had won many victories against the Japanese in the Pacific, including capturing the island of Leyte in the Philippines in October 1944, and then defeating the Japanese at the Battle of Leyte Gulf. The U.S. Marines defeated the Japanese at Iwo Jima, resulting in a famous picture of several Marines raising the American flag. But the American capture of Okinawa in June 1945 proved to be one of the bloodiest land battles of the war with Japan. It became clear that the Japanese would not agree to President Roosevelt’s demand for unconditional surrender, and that conquering Japan itself would cost the lives of perhaps a million American soldiers. (The Allied plan for possibly invading Japan was called Operation Downfall, and it was canceled once the atomic bomb attacks were successful.) The Japanese were ready to fight to the death for their country. Increasingly, Japanese fighter pilots became kamikazes by flying their planes in suicide missions directly into American ships.

President Roosevelt, who knew he was dying but kept it a secret from the American people in the election in November 1944, passed away on April 12, 1945. He thereby served less than three months of his new term. His vice president, Harry S Truman, became president despite not having been elected. Truman was a decent man from Missouri but outmatched by clever communists. Truman was not even aware that the Manhattan Project existed until late 1944. Joseph Stalin knew more about the progress of the Manhattan Project, through spies, than Truman did. Truman’s personality was to act impulsively, and he spent much of his spare time playing simple card games with friends.

He had never met Winston Churchill or other world leaders, and soon he began to meet with them as Americans were looking for ways to wrap up the war. In the summer of 1945 he received word from the Manhattan Project that the scientists had successfully built a few atomic bombs. It would be up to President Truman to decide if and how to use the atomic bomb.

Victory[edit]

Just as the American soldiers had defeated Germany in World War I, the Americans did it again (this time with help from the Soviet Union). Operation Overlord was the code name for the planned massive invasion of Continental Europe, to enable liberating France from the Nazis and conquering Germany itself. It began on “D-Day”, June 6, 1944, with the largest amphibious invasion in the history of the world when the Allied forces staged a surprise landing at Normandy, France. There were so many ships and people in the ocean that it obscured the water below. German defense forces killed many of the initial soldiers who hit the beaches, but the Americans (and British and Canadians) overpowered them and started moving through France. They were aided by the fact that Field Marshal Rommel was on leave on June 6. With America’s massive industrial capacity added to the Allies, they could now defeat the Axis Powers.

American General George Patton -- who was homeschooled -- had perfected the art of lightning-fast tank maneuvers and unrestrained aggression, and he was the only Allied leader feared by the Germans. A few years earlier, Patton led his men in war games in Atlanta that were supposed to last for many days. Patton’s aggression and the enthusiasm of his men enabled him to win the games in just a day or two. Patton inspired a unique loyalty and spirit in his men that enabled his troops to win quicker and with fewer casualties than anyone else.

Patton’s Third Army rolled through France, Belgium, Luxembourg and much of the Netherlands, routing the Germans everywhere. The best the German army could do was turn and run. The French citizens lined the streets of Paris to cheer the Free French and American soldiers when they arrived and freed the city. One of Hitler’s last orders to his general in Paris was to detonate bombs to destroy great artworks at the Louvre Museum, which holds the Mona Lisa. The Nazi general received the order but courageously disobeyed it.

Hitler did not plan on surrendering. He launched a massive counterattack at the Battle of the Bulge (December 16-26, 1944), also known as the Ardennes Campaign. This was the last major German counteroffensive against advancing Allied troops during World War II. Hitler caught the Allied forces by surprise and inflicted heavy casualties on them in the bitterly cold Ardennes Forest.

The German forces sneaked through wooded and hilly country in Luxembourg and Belgium with the goal of reaching Antwerp. The Nazis amassed three armies totaling 250,000 soldiers for a massive attack against the Allies in the Ardennes Forest. The Nazis surrounded the 101st Airborne Division in southern Belgium, and demanded their surrender. The Americans refused to surrender. This battle was the largest ever fought by the U.S. Army. Nearly 600,000 American soldiers fought in it.

Allied resistance, especially the heroic effort by the 101st Airborne division, slowed the German forces just enough to prevent the Germans from making it to Antwerp. General Patton directed the Third Army to pray, and then he counterattacked. He beat back the German pressure on the 101st Airborne Division and by February the Germans were in full retreat.

General Patton could have taken all of Eastern Europe from the Germans, and the communist Russians. Patton planned to liberate Czechoslovakia but was told to stop in 1945. He was accused of insubordination as he pleaded with his superiors to allow him to free Eastern Europe from both Nazi and communist control. His superiors would not let Patton win more victories. The communist Soviet Union then acquired control of eastern Germany and much of Eastern Europe, placing it under communist rule for most of the remainder of the century. Soviet and American troops met at the Elbe River in Germany; Hitler and his wife, Eva Braun, committed suicide. Germany immediately surrendered on May 7, 1945, and V-E Day (Victory in Europe) was May 8, 1945.

Two months later the leaders of the Allied powers traveled to Potsdam, Germany, to plan for a post-war Europe. At this Potsdam Conference were Joseph Stalin of the Soviet Union, Prime Minister Winston Churchill (who was there replaced by Clement Attlee after Churchill lost reelection in Britain), and President Truman (who had succeeded Roosevelt after his death in April). They met from July 17 to August 2.

Truman was no match for Stalin. Truman’s greatest interest was in playing cards with his “advisers”, one of whom was the communist spy Alger Hiss. Truman’s biggest concern was how Stalin might react to America’s development of an atomic bomb. Why Truman was worried about that is a mystery, as the United States was far more powerful than the Soviet Union at this point. But Truman gingerly told Stalin that America had developed a vastly more powerful bomb. Stalin simply shrugged his shoulders and took an attitude of “so what?”. One explanation is that Stalin knew more from his spies about the atomic bomb than Truman did. Another explanation is that Stalin had just acquired control of half of Germany and all of Eastern Europe and did not fear the United States in the slightest.

The big decision for Truman upon his return to the United States the first week of August 1945 was whether and how to use the atomic bomb against Japan. Historians say that Truman had already decided by late July, but had not yet given the orders. Truman was perhaps the most impulsive president in American history. He would make snap decisions and he bragged about how when he made a decision, he never second-guessed himself. Japan refused to agree to an unconditional surrender and it would have required 2 million American soldiers to invade and conquer the island. The Japanese soldiers fought to the death in hand-to-hand combat and were even engaging in suicide acts.

Some scientists (including Leo Szilard) asked Truman not to use the atomic bomb, but how else could the war be ended? Others suggested that Truman should warn the Japanese, and perhaps even display the awesome power of the bomb in a safe place to Japanese leaders before using it on cities. But for every compassionate approach, there was a counter-argument against it. Hawks (pro-war people) in America felt that if the Japanese leaders had prior warning, then they would put 100,000 of their American prisoners of war at risk and perhaps even place them in the cities we wanted to attack.

By August 1945 the mood in America was unsympathetic to the Japanese, perhaps even racist. But there is little or no evidence that racism played a role in Truman’s decision to drop the atomic bomb. All of Truman’s military advisers wanted to use the bomb. After the United States spent so much effort developing it, it was hard to imagine not using it. Also, Truman acted impulsively and decisively, and was not one to favor inaction over action. Cautious restraint was not part of Truman’s personality.

Truman and the Allied Powers had issued the Potsdam Proclamation on July 25th to the Japanese government warning of “prompt and utter destruction” if it did not surrender immediately. Afterward, Truman dropped 27 million leaflets over Japanese cities with the same warning. The Japanese ignored them and showed no interest in surrendering. If the Japanese had shown any interest in ending the war, then the atomic bomb may not have been dropped. But the Japanese wanted to keep fighting.

Truman approved the dropping of the atomic bomb, and a bomber named Enola Gay carried out the mission on August 6, 1945 on the Japanese city of Hiroshima. Truman bragged that he did not lose a night’s sleep over the decision. Truman’s reaction to the news was troubling to some. He was crossing the Atlantic on a ship and when the news reached him, he reportedly declared, “This is the greatest thing in history.” According to a witness, Truman supposedly “raced about the ship to spread the news, insisting that he had never made a happier announcement. ‘We have won the gamble,’ he told the assembled and cheering crew.” Japan, stunned, did not immediately surrender and some wonder whether it was given enough time to do so. On August 9th, a second atomic bomb was dropped, this time on the city of Nagasaki. Japan surrendered the next day, and World War II was over.

Ironically, the two Japanese cities hit by the atomic bomb, Hiroshima and Nagasaki, were two of the most Christian cities in all of Japan.

Postwar[edit]

With 60 million dead from the war and many cities destroyed, there was much work to do to rebuild. Famine and disease swept through the devastated areas of Europe. European dominance and hegemony in the world was over. Japan’s empire was conquered. There needed to be fundamental changes in both Germany and Japan.

In Germany, the Nuremberg Trials in 1946 reviewed the most heinous acts of Germans during the war. Josef Mengele fled undetected to Brazil, but other war criminals were caught, tried, and executed. Supreme Court Justice Robert Jackson was appointed as the Chief Prosecutor. Jackson, who never attended college, was known to be a brilliant, conservative judge. Evidently he conducted the trial in a fair manner, as 3 persons were acquitted and a substantial percentage avoided the death penalty. Some of the Allies, perhaps fearing the release of embarrassing information, kept Rudolph Hess (a German who had mysteriously visited England during the war) from telling what he knew and he spent most of the trial drugged up by his captors. He was sentenced to life in jail and kept from the public until he died. Twelve were executed. There were more trials afterward, leading to the execution of 250 criminals. Ever since, the Nuremberg Trials have served as a precedent for future trials for misdeeds during war.

After Japan surrendered, the United States forced it to adopt a new constitution, a parliamentary form of government, and an admission by Emperor Hirohito that he was not divine. All men and women over the age of 20 obtained the right to vote in Japan, and the emperor was reduced to the role of a figurehead, like the monarchy in England today. The new Japanese constitution prohibited Japan from declaring war. American troops occupied Japan, and General Douglas MacArthur moved there to rule over the country.

The United States helped rebuild Japan’s economy, giving it aid, loans and investments. Wartime reparations were not required. Soon Japan grew into an economy power and its goods flooded the American markets. By the spring of 1952 the formal occupation of Japan by the United States ended, and the two nations had become allies with a mutual defense treaty. However, they began competing economically instead of militarily. Later many Americans would become bitter at how much we helped Japan after the war, as competition by Japanese companies eventually caused American industries (like the car industry) to fire workers.

The Philippines suffered from the war with Japan, and the Bell Trade Act of 1946 gave the Philippines $800 million in war damages in exchange for free trade provisions. These provisions included a waiver of all import duties on goods shipped by America to the Philippines and equal access by Americans to Filipino natural resources. The Act, which both Congress and the Philippines approved, also pegged the Filipino currency (the peso) to the American dollar and prohibited the Philippines from selling products that might "come into substantial competition" with U.S.-made goods. For those reasons Filipino nationalists criticized the law as American interference in their sovereignty. In 1955, the Laurel-Langley Agreement modified this law on terms more favorable to the Philippines.

Large amounts of economic aid flowed to Europe. The Marshall Plan (named after U.S. Secretary of State George Marshall) was passed by Congress in 1948 to offer money to European nations to rebuild. Western Europe and Yugoslavia received vast aid from the Marshall Plan.

Cold War[edit]

The “Cold War” began at the end of World War II. It was hostility between communism and capitalism, and between the Soviet Union and the United States. It was “cold” because no shots were fired between the two large nations. But it was very much a war.

Even before World War II ended, the foundation was laid for the Cold War. At the conference among the Allied Powers at Yalta, a city on the Black Sea, a sick and dying President Roosevelt agreed to allow the Soviet Union to occupy eastern Germany after the war. Roosevelt also promised Stalin and the Soviet Union reparations from Germany, two warm-water ports, the Kurile Islands and Sakhalin, and railroad rights in Manchuria. What did the United States receive in return? Stalin made only two promises, neither of which was worth anything. First, the Soviet Union agreed to join the war against Japan. But the Soviet Union was no help in defeating the Japanese. Second, Stalin agreed to hold free elections in Eastern Europe. This was a complete lie and Stalin never kept that promise.

In utter disregard of his promise at Yalta, Stalin established communist governments controlled by the Soviet Union in all these eastern European countries: Czechoslovakia, Poland, Hungary, Romania, Yugoslavia, Bulgaria and Albania. These became “satellite” countries of the Soviet Union, meaning their policies revolved around and were controlled by the Soviet Union.

Germany itself was divided between communist and free portions. The eastern side became the German Democratic Republic, which was merely a communist satellite of the Soviet Union and became known as “East Germany.” The western side in 1947 became the Federal Republic of Germany. As described in a memorable post-war speech by Winston Churchill in Missouri, the Soviet Union had dropped an “iron curtain” across Eastern Europe.

Berlin, the historic capital city of Germany, was located in the communist eastern section and the Allied Powers agreed to split that city into free and communist parts. Stalin then showed his hatred of freedom by blockading the delivery of goods to the free part of Berlin, which was as easy as simply stopping the railroads from traveling to Berlin from the west. The Allies reacted by implementing a massive airlift of foods and supplies to West Berlin. Every day huge numbers of airplanes flew to and from West Berlin to carry enough cargo to support a large city. This Berlin Airlift lasted nearly 11 months, from June 1948 to May 1949, until the Soviet Union backed down and lifted the ground blockade.

A decade later, in 1961, the Soviet Union reacted to a different problem: huge numbers of refugees fleeing communism in East Berlin to live in the free West Berlin. While President Kennedy was enjoying a long, relaxing weekend, the communists built a concrete wall to separate East Berlin from West Berlin. Barbed wire was placed atop this “Berlin Wall,” and armed guards were posted along it to shoot and kill anyone trying to escape from the East into the West (no one would want to go in the opposite direction). Stories of daring and sometimes successful escapes are fascinating to read. This was the wall at which President Ronald Reagan stood in the late 1980s demanding that the head of the Soviet Union “tear down this wall!”

Back in 1945, the United Nations was set up by Soviet spy Alger Hiss, who was a confidant of Roosevelt, initially in San Francisco. The United Nations charter established a General Assembly on the principle of one vote per nation. There was an 11-member Security Council on which Great Britain, China, the United States, France and the Soviet Union had permanent seats. The other seats rotate and have representative nations from around the world. Today the Security Council has 15 seats. Any nation on the Security Council can veto any proposal. The United Nations moved to New York City where it sits today, and many feel it is ineffective or even counterproductive. Supporters of the United Nations say that it is important to promote peace and participate in peacekeeping operations.

The United States had several reactions to the Cold War. One was a policy of “containment”, whereby America helped smaller countries seeking to resist the spread of communism to them. The Truman Doctrine was a statement of support to Greece and Turkey against communist advances, and Congress authorized military and economic aid.

Military alliances formed on both sides. After the Berlin blockade in 1949, western countries joined together as the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO). In response, in 1955, the Soviet Union formed a communist alliance in the Warsaw Pact, which included all the communist countries of Eastern Europe and the Soviet Union itself. Another organization, the Central Treaty Organization (CENTO), brought together the United States, Great Britain, Pakistan, Turkey, Iran and Iraq to stop communist advances in the Middle East (Southwest Asia). SEATO, the Southeast Asia Treaty Organization, performed the same function in the Far East. Members included the United States, Great Britain, France, Thailand, Pakistan, Australia, New Zealand, and the Philippines.

Technology played a key role in the Cold War. The United States developed the atomic bomb in 1945. Using secrets stolen from the United States, the Soviet Union detonated its first atomic bomb in 1949. To stay one step ahead, the United States developed the far more powerful hydrogen bomb (H-bomb) in 1952. This used nuclear fusion and is called a “thermonuclear weapon.” The Soviet Union quickly copied it by building its own H-bomb nine months later. Both nations began to develop huge inventories of these bombs, and advocated a policy of “brinkmanship” or the willingness to do whatever was necessary to defend their interests.

The Cold War took advantage of improvements in space technology. First both the United States and Soviet Union developed intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBMs) to shoot each other with nuclear arms. Then the Soviet Union launched the first unmanned satellite, known as Sputnik I, into outer space in 1957. This greatly alarmed Americans, and the United States responded by launching its own satellite in 1958 and later initiating a mission to land on the Moon.

Americans developed a spy plane that could fly undetected at very high altitudes, called the “U-2”. When one fell to the earth (possibly shot down) in Soviet territory in 1960, President Eisenhower arranged for his Administration official to deny that America was spying. But the pilot disobeyed his orders to kill himself before being captured, and he was produced live in the Soviet Union for the television cameras! The Soviets then put him on a phony trial (known as a “show trial” because its real purpose is to humiliate an enemy), and an embarrassed United States had to beg for his return, to which the Soviets ultimately agreed in a prisoner exchange. It was never fully understood how the plane could have landed safely, and the pilot (Francis Gary Powers) died two decades later while operating a traffic helicopter. The U-2 incident forced cancellation of a meeting between President Eisenhower and the aggressive Soviet Premier Nikita Khruschev.

China[edit]

The Japanese devastated China during World War II. The Nationalist Chinese led by Chiang Kai-shek received aid from the United States to fight against the Japanese, but in reality they needed that money to prepare for civil war against the communists led by Mao Zedong. After the war, the communists attempted to conquer the Nationalists. Civil war raged from 1946 to 1949. Due to many desertions by soldiers from the Nationalist army to the communists, Mao prevailed by October 1949. Mao had promised land for the peasants and renamed the country the People’s Republic of China. Chiang fled with Nationalists to the island of Formosa, and renamed it the Republic of China (Taiwan), which the United States supported. By February 1950, the communists in the Soviet Union signed a friendship pact with the Chinese communists. Fear gripped the free world.

Chairman Mao quickly extended communist control to Inner Mongolia and Tibet in 1950-51, causing the Dalai Lama to flee to India in 1959. Tibet attempted a revolution that year, but the Chinese brutally repressed the revolution and Buddhism. India received many refugees and, after a 1962 border dispute, has been on tense terms with China ever since.

Life under Chairman Mao included an Agrarian Land Reform Law of 1950, when Mao seized property and distributed it to peasants, and a policy of forcing peasants to work on collective farms from 1952 to 1957. Women were treated like men. Mao imitated the five-year plans of the communist Soviet Union.

From 1958 to 1961, Mao implemented the misnamed “Great Leap Forward,” where he established large collective farms composed of 25,000 people working on thousands of acres per farm. These communes prohibited private possessions and everyone lived in communal housing. Predictably, people worked less and less because there was no private property as an incentive. A great famine resulted and nearly 30 million Chinese died.

Mao had a disagreement with the communists in the Soviet Union known as the “Sino-Soviet rift,” and he started to allow other communists in China to make policy. They began to use capitalist principles such as allowing people to own their land and profit from sales. In 1966, Mao reacted to this with the Cultural Revolution, where everyone intelligent or artistic was imprisoned or killed. Schools and universities were closed. Mao’s “Red Guards” (high school and college students who were militant communists) enforced the Cultural Revolution. Deng Xiaoping was imprisoned, and Zhou Enlai was placed in seclusion. Chaos reigned.

Finally Mao Zedong died in 1976, and Deng Xiaoping gained control over the radicals and ended the Cultural Revolution.

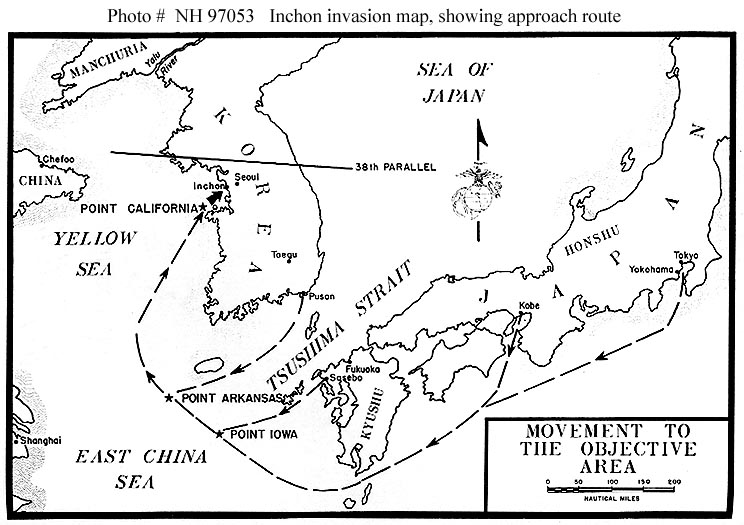

Korean War[edit]

The Cold War broke out into a real war in 1950 between communist North Korea and free South Korea. The North Koreans invaded across the 38th parallel into South Korea, which petitioned the United Nations for help. The Soviet Union at the time was boycotting its seat in the Security Council due to a decision to seat Taiwan, and thus it lacked a veto for the decision by the United Nations to send an international force to South Korea under the command of General Douglas MacArthur. But the international force was ineffective in blocking the advancing, well-trained communist soldiers from North Korea.

In September 1950, General MacArthur used an idea he had months earlier, but which all his advisers had rejected as too risky: an amphibious maneuver known as the “Inchon landing.” He turned North Korean aggression against itself by having his soldiers secretly flee on boats and then land, with reinforcements from other sources, north of the enemy to cut off their supply lines on a peninsula (see map).

That single maneuver turned certain defeat into certain victory, as the North Korean army was then stuck without supplies. But a month later communist Chinese began flooding into North Korea by the hundreds of thousands to help the fellow communists. General MacArthur wanted to defeat them also, but President Truman refused and fired MacArthur for his subordination. MacArthur had disobeyed orders from his commander-in-chief, and faced consequences for that. In July 1953, a ceasefire was signed reestablishing the 38th parallel as the dividing line. A demilitarized zone on both sides exists to this day.

The North Korean dictator, Kim Il Sung, ruled the country for decades and was succeeded by his son, Kim Jong Il, who then alarmed the world by saying he has nuclear weapons. He passed away and has been succeeded by his son. South Korea, meanwhile, has grown, with capitalism, far stronger than North Korea. South Korea had its first free elections in 1987.

Repeated attempts to reunite North and South Korea have been total failures, as North Korea remains completely communist (like China and Cuba) while South Korea is one of the most Christian and free enterprise nations in the world. The South Korean electronics company Samsung has risen to dominance in the computer video market (it first made remarkable computer and television screens, and then made the Android smart phone), and the South Korean car company Hyundai has also been successful in competing against the Japanese and American companies.

References[edit]

- ↑ http://www.time.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,760539,00.html

- ↑ http://www.george-orwell.org/l_biography.html

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 http://www.worldwar2database.com/html/holocaust.htm

- ↑ http://www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org/jsource/Holocaust/history.html

- ↑ http://www.nsa.gov/about/_files/cryptologic_heritage/publications/wwii/eavesdropping.pdf

Categories: [World History lectures]

↧ Download as ZWI file | Last modified: 02/23/2023 01:47:21 | 68 views

☰ Source: https://www.conservapedia.com/World_History_Lecture_Twelve | License: CC BY-SA 3.0

ZWI signed:

ZWI signed:

KSF

KSF