Kings, Books Of

From Nwe

From Nwe | Books of the |

The Books of Kings (Hebrew: Sefer Melachim ספר מלכים) are a part of the Hebrew Bible narrating the history of the kings of Judah and Israel from the end of the reign of King David through the beginning of the Babylonian exile. Kings was originally written in Hebrew, and it was later included by Christianity as part of the Old Testament.

Throughout the narrative, the author looks back to the golden age of David's reign as a paragon of righteousness, with the most important virtue of a king being his devotion to the Hebrew God Yahweh and a determination to rid the land of pagan religious practices.

Solomon's reign is truly glorious, and he builds the Temple of Jerusalem, God's abode on earth, where all Israelites must come to offer sacrifice. The division of Solomon's united kingdom into separate northern and southern nations is attributed to Solomon's sin of erecting altars to foreign gods in honor of his many wives, the daughters of neighboring kings.

The first northern king, Jeroboam I, is originally supported by God, but commits a serious sin by establishing two national shrines that make it supposedly unnecessary for his people to go to Jerusalem to offer sacrifices to Yahweh. From this point on, the kings of Israel, even when they passionately oppose pagan worship, all repeat Jeroboam's sin by supporting the shrines at Bethel and Dan. The prophets Elijah and Elisha emerge as God's champions to bring Israel to repentance, and eventually Elisha succeeds in bringing Jehu, a strong partisan of Yawheh, to the throne. However, although he rids the land of Baal worship, even Jehu fails to destroy the unauthorized Yahwist altars at Bethel and Dan. Eventually, the Assyrian Empire rises up as God's agent to punish Israel's sin, and the people of the northern kingdom are taken into exile around 722 B.C.E.

The kings of Judah sometimes do well in attempting to rid the land of pagan practices, but none goes far enough until the coming of King Josiah in the sixth century B.C.E. Yet, although Josiah is exemplary in every respect, it is already too late for Judah, as God has determined to force His people into exile in Babylon, where they will be duly chastened. The book ends with the destruction of Jerusalem and the captivity of the people of Judah who have been taken to Babylon by the forces of Nebuchadnezzer II in 586 B.C.E.

Although it ends tragically, with Israel destroyed and Judah in exile, the story told in the Books of Kings provides the main record of God's providence to establish a kingdom for his chosen people in the land of Canaan, where they could build a nation strong enough to resist foreign aggression, centering on God's Temple as an inspiration not only for the Israelites, but for all mankind.

Contents

Introduction

The Books of Kings contain accounts of the kings of the ancient Kingdom of Israel and the Kingdom of Judah from the accession of Solomon until the subjugation of Judah by Nebuchadnezzar and the Babylonians—a period of roughly 450 years. They synchronize with 1 Chronicles 28 through 2 Chronicles 36:21. However, Chronicles ignores much of the history of the northern kingdom and gives greater prominence to the priestly office, while Kings gives greater prominence to the monarchy. Kings appears to have been written considerably earlier than Chronicles, and many of the narrations in Kings are copied verbatim in Chronicles.

The story in Kings takes up the account left off in the Books of Samuel (2 Sam. 15-20), which ended with the rebellions of Absalom and Sheba, supported by the northern tribes, against the reign of King David. The following is a detailed summary of the contents of the Books of Kings:

David's death and Solomon's reign

- Adonijah and Solomon (1 Kings 1:1-2:46)—During his old age, David spends his nights with Abishag, a very young woman appointed for the purpose of "keeping him warm." Adonijah, David's eldest son, gathers attendants and persuades the military commander Joab and high priest Abiathar to support his claim to the throne. Opposed to this are the priest Zadok, the military leader Benaiah, and the prophet Nathan. Nathan conspires with Bathsheba, the mother of Solomon, to influence David to appoint Solomon as his heir and have him anointed immediately as king. When Adonijah is told of this, he and his supporters flee, and Adonijah seeks sanctuary at the Jerusalem altar. Solomon promises not to harm him if he proves worthy. David, on his death bed, instructs Solomon to take revenge on Joab and others against whom David bears a grudge. Later, Adonijah approaches Bathsheba and asks to wed Abishag, but when Bathsheba brings the request to Solomon, he interprets it as treasonous and has Benaiah execute Adonijah. The high priest Abiathar, who had supported Adonijah, is then deposed and replaced by Zadok. Joab seeks sanctuary at the sacred altar, but is killed there by Benaiah. Later, Benaiah also kills a man name Shimei, a supporter of King Saul who had cursed David when he fled from Absalom's rebellion. The narrator concludes: "The kingdom was now firmly established in Solomon's hands."

- The Wisdom of Solomon (1 Kings 3:1-28 and 5:9-14)—After having cemented an alliance with Egypt by marrying the daughter of Pharaoh, Solomon goes to Gibeon, the most prominent of the high places, to offer sacrifices. When God appears to Solomon and grants him a wish, the king asks only for wisdom. God grants this, and promises both riches and great power as well. As a demonstration of his wisdom, the story is related of two prostitutes who come to Solomon and ask him to settle an argument between them as to who is the true mother of a baby claimed by both. Solomon asks for a sword to cut the baby in half. When one of them tells him to give the baby to the other rather than kill it, he recognizes her as the true mother. Solomon is lauded as the wisest and most powerful of the kings in the entire world, who created thousands of songs and proverbs, and whose fame was unparalleled in his day.[1]

- Solomon's officials (1 Kings 4:1-19, and 5:7-8)—An extensive list is given of the officials of Solomon's court and their duties.

- The Temple (1 Kings 5:15-7:51)—Solomon and King Hiram of Tyre enter into a trade agreement providing Solomon with raw materials and craftsmen to build a great Temple of Yahweh in Jerusalem. Solomon conscripts workers to build the Temple, which takes seven years to complete. A detailed description is given of its construction and elaborate furnishings. Solomon also builds a palace for himself, which is larger than the Temple and takes 13 years to construct.

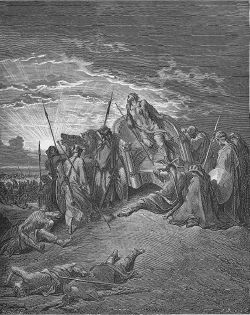

A late nineteenth-century artist's conception of the Ark of the Covenant, employing a Renaissance cassone for the Ark and cherubim as latter-day Christian angels.

A late nineteenth-century artist's conception of the Ark of the Covenant, employing a Renaissance cassone for the Ark and cherubim as latter-day Christian angels.

- The Ark comes to the Temple (1 Kings 8:1-9:9)—The elders of the tribes of Israel assemble, and the Ark of the Covenant is moved from its tent sanctuary to the Temple. A dark cloud fills the Temple, indicating Yahweh's presence. Solomon offers a prayer of fidelity and then receives a promise from Yahweh that Solomon's descendants would remain on the throne in Jerusalem forever, "if you walk before me in integrity of heart and uprightness, as David your father did." (1 Kings 9:4)

- Territory ceded to Hiram (1 Kings 9:10-14)—Hiram of Tyre is given 20 towns in Galilee by Solomon, in exchange for a large quantity of gold. Hiram, however, is not pleased with them.

- Solomon's building projects (1 Kings 9:15-25)—Solomon uses slave labor to strengthen and expand Jerusalem, Hazor, Megiddo and Gezer. [2] Gezer, had previously been burnt to the ground by Pharaoh, who then presented it to his daughter as a dowry. For this building program, Solomon reportedly enslaves every Canaanite still living in the land. Solomon also improves a palace he has constructed for his wife, Pharaoh's daughter.

- The Queen of Sheba (1 Kings 10:1-10, and 10:13)—The Queen of Sheba visits Solomon, bringing with her many precious gifts, and is deeply impressed by his wisdom and organizational skills.

- Solomon's wealth (1 Kings 4:20-5:6, 9:26-28, 10:11-12, and 10:14-29)—Solomon's empire stretches all the way from the Euphrates to Egypt, and many vassal states pay him tribute. His riches, described in great detail, are greater than "all the other kings of the earth."

- Solomon's sin (1 Kings 11:1-13)—Apart from his Egyptian wife, Solomon also has over 700 royal wives and 300 concubines from surrounding tribes and nations. To honor them and their people, he constructs high places venerating such deities as Astarte, Milcom, and Chemosh. As a result, Yahweh informs Solomon that "I will most certainly tear the kingdom away from you and give it to one of your subordinates."

- Solomon's enemies (1 Kings 11:14-25)—In the later part of his reign, the unity of Solomon's empire begins to erode. Hadad of Edom, who had fled to Egypt during David's conquest of his nation, returns from exile and opposes Solomon's hegemony. Rezin of Damascus emerges as Solomon's adversary to the northeast in Aram/Syria. Trouble also brews for Solomon nearer to home in the person of a promising young leader, Jeroboam, whom Solomon appoints to lead the forced laborers of the tribe of Ephraim in Jerusalem. The prophet Ahijah of Shiloh predicts that Jeroboam will one day become the ruler of the ten northern tribes. Sensing a threat, Solomon seeks to kill Jeroboam, who—like Hadad of Edom in the last generation—flees to exile in Egypt.

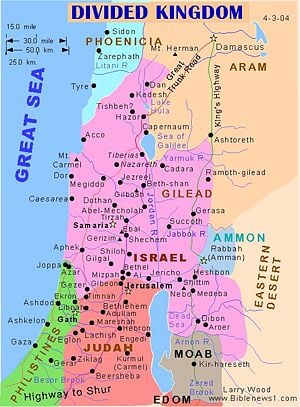

Divided Kingdoms

- Rehoboam (1 Kings 11:41-12:1, 12:3-19, 12:20b-24, and 14:21-31a)—When Solomon dies, his son, Rehoboam, is proclaimed king at Shechem. The people of Israel appeal to have their servitude lightened, but Rehoboam only threatens to increase their burden. This results in rebellion, and when Rehoboam sends out his minister of forced labor, Adoram, to conscript workers, the people stone him to death. Rehoboam flees to Jerusalem, as only Judah remains loyal to him.[3] Rehoboam plans an attack to force the rebelling tribes into submission, but a "man of God," named Shemiah dissuades him. Later in Rehoboam's reign, Shishak of Egypt attacks, looting the Temple of Jerusalem and palace. Despite the prophet's warning, the text relates that "There was continual warfare between Rehoboam and Jeroboam."

- Jeroboam I (1 Kings 11:26-40, 12:2, and 12:25-32)—The prophet Ahijah had said to the younger Jeroboam: "If you do whatever I command you and walk in my ways... I will build you a dynasty as enduring as the one I built for David and will give Israel to you." Thus, when Israel rebels against Rehoboam, its people appoint Jeroboam, who has returned from Egypt, as their new king. Jeroboam establishes Shechem as his capital and fortifies Penuel. Later he moves to Tirzah. To provide an alternative pilgrimage site to the Temple of Jerusalem, Jeroboam establishes national shrines at the Bethel and Dan. This act is considered a heinous sin by the author of Kings, who consistently refers to as the root cause of evil in the northern kingdom. Jeroboam loses a key supporter in Ahijah the prophet, but succeeds in maintaining the unity of his kingdom and resisting Rehoboam's attacks. In 1 Kings 14:1-20, Jeroboam's son and heir, Abijah, becomes sick, so Jeroboam sends his wife, in disguise, to Ahijah, to ask what can be done. Ahijah replies that Jeroboam's sin has condemned his dynasty to destruction, and Abijah is doomed. When the wife returns and enters her house, the son dies.

- Bethel condemned (1 Kings 12:33-13:34)—Jeroboam prepares to make a sacrifice at Bethel, but at that moment, an unnamed man of God prophesies the future destruction of the site by King Josiah of Judah. Jeroboam orders that the man be seized, but his arm freezes and the altar collapses. The man of God restores Jeroboam's arm. After the prophet leaves, however, he is killed by a lion because he accepts the hospitality of a fellow prophet in violation of God's command.

The early kings of Israel and Judah

The narrative now adopts a much more sketchy approach to his history, leapfrogging from south to north. Because the names of the northern and southern kings are often similar and sometimes identical, the storyline can be difficult to follow. Its focus is religious, mentioning political and economic events only in passing. Theologically, it demonstrates how God blesses kings that obey him by destroying heathen altars and how those who fail to do God's will are cursed. The Kingdom of Israel is virtually doomed from the outset, as even the best of its kings (in the narrator's opinion)—the passionately pro-Yahwist Jehu—continues to support the shrines established by Jeroboam at Bethel and Dan. Judah's kings do better, but none of them will measure up to God's standards until the coming of Josiah near the end of the narrative.

- Abijam of Judah (1 Kings 14:31b-15:8a)—After Rehoboam dies, his son Abijam (named Abijah in Chronicles) succeeds him as king of Judah. Abijam is said to be a descendant of Absalom on his mother's side. Abijam continues the war against Jeroboam to conquer Israel. He is declared to be a bad king for failing to rid Judah of idol worship.

- Asa of Judah (1 Kings 15:8b-24a)—Abijam's son, Asa, succeeds him as king of Judah, and is praised for deposing his grandmother, Maacah, who had been a worshiper of Asherah.[4] War continues against the north, and Asa scores a coup when he bribes Israel's ally, Ben-Hadad of Aram, to switch sides by sending him the treasures in the Temple and palace.

- Baasha of Israel (1 Kings 15:25-16:6a)—When Jeroboam dies, his son, Nadab, takes over as king of Israel. However, Baasha overthrows him and slaughters all the remaining relatives of Jeroboam. During Baasha's reign, there is a permanent war with Judah. When Ben-Hadad turns against him, Baasha loses considerable territory and is forced to abandon a major building project at Ramah. A prophet named Jehu declares that Baasha has been punished for his actions against Nadab, even though they had fulfilled Ahijah's earlier prophecy.

- Zimri (1 Kings 16:6b-20)—After the death of Baasa, he is succeeded by his son, Elah. However, one of Elah's leading commanders, Zimri, assassinates him and briefly takes over the throne of Israel. A major faction of the army, however, proclaims their leader, Omri, as king, and lay siege to Zimri at Tirzah. Zimri burn his own palace to the ground, killing himself.

- Omri (1 Kings 16:15b-19, 16:21-28a)—Only half of the army of Israel supports Omri, the other half supporting a man named Tibni. The civil war ends with Omri and his supporters as victors. Omri later constructs a new capital at Samaria, and moves there. He reigned 12 years. Despite the many monumental achievements and constructions that are archaeologically attributed to Omri's reign, the Book of Kings neglects to mention any of these, preferring to portray Omri as an insignificant and evil king whose main accomplishment was to become the father of the truly evil Ahab. Omri is the first of either Judah's or Israel's kings to be recognized in the historical record outside of the Bible.

- Ahab(1 Kings 16:34) - After the death of Omri, his son, Ahab, becomes the king. Ahab marries Jezebel, a princess of Tyre and notorious Baal-worshiper who persecutes the prophets of Yahweh, and for whom Ahab erects a Temple of Baal in Samaria. Because of this, Ahab is considered one of the most evil of the northern kings. During the reign of Ahab, a man named Hiel rebuilds Jericho from its ruins. The prophet Elijah emerges as the central figure of God's providence during Ahab's reign.

The Elijah cycle

Here the narrative is interrupted by the stories of the northern prophets Elijah and Elisha, apparently from an independent source or sources. The stories of these prophets are interspersed with the narrator's usual material and give additional details about the reigns of Ahab of Israel and his successors. The northern kingdom thus receives extra emphasis in these sections.

- Elijah and the widow (1 Kings 17:1-24)—Elijah's first prophecy is a dire one—that no rain shall fall in Israel except by God's express command. He travels to the Brook of Kherith, where he is fed by ravens. From there he is sent to the house of a starving widow, whom he miraculously provides with endless flour and water. When the widow's son nevertheless dies, Elijah revives him by stretching his body out on the boy's three times in succession.

- Elijah at Carmel (1 Kings 18)—Meanwhile, the famine grows bitter, and Elijah is sent by God to Ahab, who accuses him for being the "disturber of Israel" because he has caused the drought. The two men arrange a contest between Elijah and the prophets of Baal at Mount Carmel. Elijah dramatically defeats them with God's help and then commands the onlookers to slaughter all 450 of them. Afterward, Elijah prays, and Yahweh finally sends rain to the land. Jezebel, however, seeks Elijah's life, and he flees to the south.

- Elijah's at Horeb (1 Kings 19:1-21)—Going first to Beersheba, Elijah prays for death, but is ordered by an angel to eat and drink. He walks for 40 days and nights to Horeb, the very mountain where Moses first met Yahweh. There he experiences a dramatic epiphany. He is ordered to go and anoint Hazael as the next king of Syria, Jehu as king of Israel, and Elisha as his own successor. Elisha, a plowman, immediately leaves his fields readily follows Elijah. The other two tasks are apparently left to Elisha's ministry.[5]

- The first siege of Samaria (1 Kings 20:1-21)—Ben-Hadad, the king of Aram/Syria, lays siege to Samaria, and Ahab gives up his treasure, as well as elements of his harem and sons, probably as hostages. Ben-Hadad then demands to be allowed to search Ahab's property, but the elders of Israel dissuade Ahab from agreeing, angering Ben-Hadad. A prophet arrives and tells Ahab that he will defeat Ben-Hadad, so Ahab gathers the army of Israel, and they launch a surprise attack, causing the Arameans to flee.

- The battle of Aphek (1 Kings 20:22-43)—The servants of Ben-Hadad tell him to attack on the plains, as the God of Israel is a god of the mountains. Ben-Hadad goes to the plain of Aphek, but the unnamed prophet again tells Ahab that he will win, so Ahab gathers his army and strikes. The Arameans flee into the city of Aphek, but its walls collapse. Ben-Hadad sends messengers to Ahab to beg for mercy, and Ahab grants it. A prophet soon informs Ahab, however, that he has doomed himself because God had intended Ben-Hadad's death.

- Naboth's vineyard (1 Kings 21:1-29)—Ahab tries to buy the vineyard of a man named Naboth, located near the palace in Samaria, to use as a vegetable garden. Naboth refuses, which angers Ahab and causes Jezebel to arrange for Naboth's death on trumped up charges of treason. Once Naboth has been killed, Ahab meets Elijah, who prophesies: "I bring disaster on you. I will consume your descendants and cut off from Ahab every last male in Israel." Ahab then repents, so Yahweh is moved to put off punishing against him. [6]

- The Battle of Ramoth-gilead (1 Kings 22:1-40a, and 22:54)—After a period of peace between Aram and Israel, Jehoshaphat of Judah approaches Ahab and enters a pact to help take back Ramoth-gilead from Aram. Ahab's court prophets[7] confirm the plan, but Jehoshaphat asks for another opinion. Ahab summons Micaiah, son of Imlah. Micaiah at first agrees with the other prophets, but, pressed by Ahab, predicts total failure. The prophet Zedekiah immediately slaps him and challenges his oracle. Ahab orders Micaiah imprisoned. He then disguises himself to enter the battle, and Jehoshaphat joins him in full royal array. A randomly fired arrow hits the disguised Ahab, and he eventually dies from blood loss. The king's body is washed at a pool in Samaria, and the blood on his chariot is licked up by the dogs, supposedly fulfilling Elijah's prophecy.

- Jehoshaphat (1 Kings 15:24b and 22:41-51a)—Jehoshaphat, already mentioned in the story of Ramoth-gilead, succeeds his father, Asa, as king of Judah. He is judged as having done "what was right in the eyes of the Lord," especially in getting rid of the male shrine prostitutes of Judah. He also ends the warfare with Israel.[8] However, he tolerates the high places. Like Solomon, Jehoshaphat builds ships with the intention of sending them to Ophir for gold, but they were wrecked at Ezion-gezer.

- Ahaziah of Israel (1 Kings 22:40b, and 1 Kings 22:52-2 Kings 1:18)—Ahaziah, Ahab's son, succeeds him as king of Israel. Like Ahab, he continues the "sin of Jeroboam" in supporting the shrines at Bethel and Dan, and compounds this by honoring Baal. His reign is a short one, however, as he falls through the lattice of his roof terrace and is mortally wounded. Messengers are sent to Ekron to consult with the diviners of the city as to Ahaziah's prognosis. Elijah intercepts the messengers and tells them that Ahaziah is destined to die, not because of his injuries, but because he has consulted a foreign deity. On two separate occasions, Ahaziah sends a military company of 50 men to bring Elijah to him, but Elijah commands fire from heaven to consume them. The third time, the angel of Yahweh stops Elijah before he can act against the men. He goes with them to Samaria and tells Ahaziah to his face that "you will never leave the bed you are lying on."

The Elisha cycle

Here begins the story of Elisha as the central prophetic figure of Israel, taking up the mission given earlier to Elijah. God tells Elijah:

Anoint Hazael king over Aram. Also, anoint Jehu son of Nimshi king over Israel, and anoint Elisha son of Shaphat from Abel Meholah to succeed you as prophet. Jehu will put to death any who escape the sword of Hazael, and Elisha will put to death any who escape the sword of Jehu. (1 Kings 19:15-17)

- The last days of Elijah (2 Kings 2:1-18)—Elisha and Elijah are on their way to Gilgal, but Elijah tells Elisha to remain behind. Elisha insists on accompanying his master. He passes a similar test a second and a third time, finally crossing the Jordan with him. Elijah offers him a final boon, and Elisha asks for "a double portion of your spirit." A flaming chariot and horses then come to collect Elijah and take him to heaven. Elisha picks up Elijah's mantle, which had fallen, and strikes the waters of the Jordan as Elijah had done earlier. The waters part, and Elisha crosses back over where he is greeted as the "son of the prophets" and recognized as their new leader.

- The miracles of Elisha (2 Kings 2:19-24, 4:1-7, 4:38-44, and 6:1-7) At Jericho, Elisha magically purifies the local waters, which have gone bad. At Bethel, where a large number of young boys shout "bald-head" at him, Elisha curses them, resulting in two bears coming out of the forest to tear 42 of the boys to pieces. Elisha then rescues the widow of one of the prophets from her husband's creditors by miraculously multiplying the tiny amount of oil that she possesses. During a famine, Elisha miraculously feeds the prophets at Gilgal with a nourishing stew made of apparently poisonous gourds. A man from Baal-shalishah brings Elisha 20 loaves, and Elisha manages to feed a hundred people with them. Finally, when a group of prophets lose a valuable iron axe-head in the Jordan, Elisha causes it to float to the surface.

- Joram of Israel (2 Kings 1:17b and 3:1-27)—Due to Ahaziah, son of Ahab, being childless, his brother Jehoram—called Joram to distinguish him from Jehoram of Judah—succeeds him as king of Israel. Moab stops sending tribute and musters its army against Israel. Joram responds by making a pact with Jehoshaphat of Judah, and the combined forces of Israel, Judah, and Edom (a vassal of Judah), set out to attack Moab. When their water supply becomes exhausted, they consult Elisha. He reluctantly agrees to assist them, and, going into a trance, prophesies both water and victory. The Moabites, thinking Joram's alliance has begun to fight among themselves, unwisely attack and are vanquished. Their besieged king sacrifices his son to Chemosh, resulting in Israel's withdrawal.[9]

- Elisha and the Shunemite woman (2 Kings 4:8-37)—In a story remarkably similar to that of Elijah and the widow's son, Elisha visits Shunem, where a woman asks him to dine with her, and he becomes her regular guest. Elisha returns her hospitality by telling the woman, who is childless, that she will become pregnant. She gives birth to a boy, but after a few years, he becomes ill and dies. Elisha revives him by lying on top of him twice.

- Naaman and Gehazi (2 Kings 5:1-27)—Naaman, commander of Aram's forces, captures a girl from Israel during one of his campaigns. The girl tells Naaman, who suffers from leprosy, that Elisha can heal him. The king of Aram therefore sends Naaman to Elisha with letters of recommendation. Elisha orders Naaman to wash in the River Jordan seven times, and when he does so, he is cured. Elisha refuses payment, but his servant, Gehazi, goes after Naaman and suggests that he donate money and two festal garments, which Naaman does. However, when Gehazi returns to Elisha, the prophet curses him with the leprosy that Naaman previously had.

- The Battle of Dothan (2 Kings 6:8-23)—The king of Aram suspects, rightly, that Elisha is informing the king of Israel of his battle plans. He sends an army to kill Elisha at Dothan. Elisha, knowing that he is protected by Yahweh's own army, strikes the army of Aram blind and leads them to Israel's capital, Samaria. "Shall I kill them, my father?" asks the delighted king of Israel, probably Joram. "Shall I kill them?" But Elisha orders a feast instead. The Aramaeans leave, and they are said never to return again to Israel, at least until the next chapter.[10]

- The second siege of Samaria (2 Kings 6:24-7:20)—Ben-hadad, king of Aram, lays siege to Samaria. The siege causes terrible monetary inflation, and a famine that is so severe that some people have started eating other people's children. The king of Israel attributes the disaster to Yahweh's judgment, but Elisha prophesies a rapid end to the crisis. God causes the Arameans to flee, and the famine is lifted.

- Hazael of Aram (2 Kings 8:7-15)—Ben-hadad of Aram lies sick, and sends his lieutenant, Hazael, to consult Elisha. The great prophet instructs Hazael to tell the king he will survive, but confides to Hazael that the king will actually die and that Hazael will succeed him. Hazael returns and tells Ben-Hadad he will recover, then smothers the king to death and takes his place. The story seems to fulfill the earlier prophecy that Elijah, though acting through Elisha as his agent, would anoint Hazael to be king of Aram.

- Jehoram of Judah (2 Kings 8:16-24)—Jehoram, the son of Jehoshaphat, succeeds his father as king of Judah. Jehoram continues his father's alliance with Israel, having married Ahab's daughter Athaliah. Unlike his father, however, Jehoram is said to "walk in the ways of the kings of Israel." Edom, previously on Judah's side, revolts, and although he fights bravely, Jehoram does not succeed in subduing the rebels.

- Ahaziah of Judah (2 Kings 8:24b-29 and 9:27-29) When Jehoram of Judah dies, his son Ahaziah rules over Judah in his place.[11] Ahaziah supports Joram of Israel, his mother's brother, at the battle of Ramoth-gilead, and visits Joram while he is convalescing from his battle wounds. He dies there, a victim of Jehu's coup (see below).

- Jehu (2 Kings 9:1-10:31)—Elisha sends a young prophet to anoint Jehu, one of Joram of Israel's military commanders. The prophet commands Jehu to put an end to the House of Ahab and seize the throne of Israel. Jehu moves immediately against Joram and assassinates him. Ahaziah of Judah, who is visiting the wounded Joram, is also murdered on Jehu's orders. Jehu then heads to Jezreel and orders that Jezebel, Joram's mother, be thrown from a high window to her death, where she is left to be devoured by dogs. He proceeds to supervise the slaughter of 70 of Ahab's male descendants and 42 relatives of Ahaziah of Judah, who have the misfortune to meet him on the road. Jehu then pretends to be a worshiper of Baal and invites the priests of Baal to join him in that deity's temple. After closing the gates, he orders everyone inside killed. The temple of Baal is then destroyed, and turned into a public toilet. The narrator praises Jehu for ridding Israel of Baal worship but criticizes him for committing the "sins of Jeroboam son of Nebat" by supporting the Israelite shrines at Bethel and Dan instead of the Temple of Jerusalem. Despite Jehu's zeal for Yahweh, the narrator notes that Hazael of Aram succeeds in diminishing Jehu's territory considerably.[12]

- Athaliah (2 Kings 11:1-20)—Jehu's coup has ironically left one descendant of Ahab alive and in a position of great influence. Athaliah, the mother of Ahaziah of Judah, is also the daughter of Ahab and Jezebel. On discovering the murder of her son and entire paternal extended family by Jehu, she sets out to take revenge by seizing the throne of Judah for herself. She attempts to do away with Ahaziah's male heirs, but his sister—no doubt a half-sister and not Athaliah's daughter—manages to hide Ahaziah's infant son Joash in the Temple of Yahweh. Athaliah rules for six years, the only reigning queen of either Judah or Israel. During her days, a temple of Baal reportedly exists in Jerusalem, although it is not clear when it may have been built. At the end of this time, the high priest Jehoiada orchestrates a coup against Athaliah. She is killed, and little Joash becomes king. The temple of Baal is consequently destroyed, and its high priest is put to death.

The later Kings

The narrative now resumes it normal style and rhythm as it describes the reigns of the Kings of Israel and Judah after the destruction of Ahab's line.

- Joash of Judah (2 Kings 12:1-22a)—Joash (a short form of Jehoash, to distinguish him for a northern king of the same name) becomes king at the tender age of seven. Under the tutelage of Jehoiada the priest, he encourages the strict worship of Yahweh in Jerusalem itself, but disappoints the authors for tolerating the continued existence of the high places. Repairs are made to the Temple of Jerusalem, which had become dilapidated under the rule of Athaliah and her predecessors. However, when Hazael of Aram mounts an attack on Jerusalem, Joash is forced to buy him off with the treasures from the Temple. At the end of his 40-year reign, Joash is killed by his own men.

- Jehoahaz of Israel (2 Kings 10:32-35a, and 13:1-9a)—During Jehu's reign, Hazael conquers Gilead and other eastern territories belonging to Israel. After he dies, his son, Jehoahaz, becomes the new ruler of the much reduced kingdom. Under the yoke of Hazael, Jehoahaz turns to Yahweh, and a savior is sent to free Israel from Hazael.[13] Jehoahaz, like all of Israel's kings, continues to commit the "sins of the house of Jeroboam." Hazael's aggression results in the near obliteration of Israel's military power.

- Jehoash of Israel (2 Kings 13:9b-13a, 13:13c-25 and 14:13-16a): Jehoash succeeds Jehoahaz, his father, as king of Israel.[14] Jehoash goes to Elisha, who is dying, for help against Hazael. Elisha commands Jehoash to shoot an arrow through the window, and then prophesies that his doing so has ensured victory against Hazael. Later, Hazael dies and is succeeded by the weaker Ben-hadad, who is defeated three times by Jehoash, in fulfillment of Elisha's predictions. When Israel is then attacked by Judah, Jehoash succeeds in punishing his southern neighbor and even conquers its capital.

- Amaziah (2 Kings 12:1-22b, 14:1-14 and 14:17-21)—Amaziah, the son of Joash of Judah, succeeds him as king. Amaziah slaughters those who killed Joash, but allows their descendants to live. He succeeds in subjugating Edom and then attacks Israel. However, Judah is defeated, and Amaziah is captured. Jehoash of Israel breaks through the walls of Jerusalem and pillages the Temple. After Jehoash' death, the now freed Amaziah hears of a conspiracy against him in Jerusalem and flees to Lachish, but is pursued there and killed.

- Jeroboam II (2 Kings 13:13b and 14:23-29a)—Jeroboam II becomes king of Israel after the death of Jehoash, his father. Despite committing the "sin of Jeroboam son of Nabat" Jeroboam II is otherwise a hero, as he manages to expand the boundaries of Israel as far as the Arabah, defeats Aram, and reportedly even captures Damascus. Other sources indicate that Israel grew particularly prosperous under his reign, which lasted 41 years.

- Uzziah/Azaraiah and Jothan (2 Kings 14:22, 14:29b-15:7b, 15:32-36, and 15:38a)—The son of Amaziah, Uzziah (called Azariah in Kings but generally acknowledged as Uzziah), succeeds him as king of Judah, and rebuilds the Elath in the former territory of Edom. However, Uzziah suffers from leprosy, so his son, Jotham, reigns as regent. Jotham formally becomes king when Uzziah actually dies. More details of Uzziah's life are given in Chronicles. His reign coincides with the early years of Isaiah's ministry.

- Zechariah, Shallum, and Menahem (2 Kings 15:8-22a)—Jeroboam II is succeeded by Zechariah, his son, as king of Israel, but Zechariah is soon killed by Shallum, who reigns in his place. Menahem soon kills Shallum and takes bloody vengeance against those that did not support him. During Menahem's reign, the king of Assyria, Tiglath-pileser (referred to as Pul) invades and forces Menahem to pay heavy tribute to him, which Menahem raises by taxing the population.

- Pekahiah and Pekah (2 Kings 15:22b-31 and 15:37)—When Menahem dies, his son, Pekahiah, succeeds him as king. However, Pekah, the adjutant to Pekahiah, conspires certain Gileadites, and kills Pekahiah, becoming king in his place. Pekah enters into an alliance with Rezin, King of Aram, to attack Judah. Supporting Judah, now a vassal of Assyria, Tiglath-pileser invades Israel, capturing several cities, and deporting their populations. Hoshea conspires against Pekah, killing him and becoming king in his place (though an inscription by Tiglath-pileser states that he killed Pekah and placed Hoshea on the throne himself).

- Ahaz (2 Kings 15:38b-16:20a)—Ahaz becomes king of Judah when his father, Jotham, the son of Uzziah, dies. The combined forces of Aram and Israel besiege Ahaz. Edom is able to recover Elath, and Ahaz becomes a vassal of Tiglath-pileser, Israel's adversary. Tiglath-pileser then attacks Damascus (capital of Aram), killing Rezin, and deporting the inhabitants to another part of Assyria. One of Judah's most depraved kings, Ahaz is condemned by the authors for sacrificing at the high places and Asherah groves, and even sacrificing his son to Moloch. When Ahaz goes to Damascus to meet Tiglath-pileser, he is so impressed by the altar there that he has a new one made to the same design for the Temple of Jerusalem. Ahaz makes further alterations to the Temple layout, in deference to the Assyrian king.

- Hoshea and the Lost Tribes (2 Kings 17:1-41 and 18:9-12)—After taking control of what remained of Israel, Hoshea is forced to become a vassal of the Assyrian Empire. However, Hoshea resents this, and not only fails to send the annual tribute to Assyria, but appeals to Egypt for help. In consequence, Shalmaneser of Assyria occupies Israel and besieges the capital, Samaria, for three years. Samaria falls to his successor, Sargon II (identified only as the king of Assyria), and the Israelites are deported to other regions of the Assyrian empire. Sargon imports other Assyrian people to populate vacated lands. Due to attacks by lions, Sargon understands that the "God of the land" is displeased and sends Israelite priests back to teach the new inhabitants how to propitiate Yahweh. The mixed population of remaining Israelites and Assyrian immigrants would later intermarry and be known as the Samaritans. The Kingdom of Israel thus comes to an end.

Judah stands alone

- Hezekiah's reform (2 Kings 16:20b, and 18:1-6)—The son of Ahaz, Hezekiah, institutes a far reaching religious reform in Judah, centralizing the religion focusing on the Temple of Jerusalem, for which he is strongly approved of by the narrator. In iconoclastic pursuit of the reform, Hezekiah destroys the high places, sacred pillars, and Asherah poles,[15] as well as the bronze serpent created by Moses, which had long been housed in the Temple but was now considered idolatrous.

- The siege of Jerusalem (2 Kings 18:13-19:37)—Hezekiah rebels against Assyria and partially subjugates the land of the Philistines (2 Kings 18:8). However, Sennacherib, the king of Assyria, retaliates and captures all of the cities of Judah except Jerusalem. Hezekiah uses the Temple funds, even breaking up the gold plated doors, to attempt to buy him off. An Assyrian commander is sent to Jerusalem to demand full capitulation. Hezekiah sends messengers to Isaiah who prophesies that Yahweh will protect Jerusalem for the sake of the promise made to David, and the Assyrians will not be able to take the city. That night an angel kills 185,000 men of the Assyrian army, and the survivors return to Assyria.[16] Sennacherib is then killed by two of his own sons, and a third becomes king in his place.

- Hezekiah's illness (2 Kings 20:1-20a, and 20:20c-21a)—Isaiah visits Hezekiah on his deathbed to tell him to prepare for death, but when Hezekiah prays that his faithfulness will be remembered by Yahweh, God instructs Isaiah that 15 years have just been added to Hezekiah's life. Isaiah then gets a poultice to apply to Hezekiah's infected boil, and the king miraculously recovers. Merodach-baladan, the son of the Babylonian king, sends get-well gifts to Hezekiah, and Hezekiah shows the Merodach-baladan's messengers his treasures. Isaiah disapproves of this and prophesies that having seen the treasure, Babylon's greed will cause them to invade and take it away, and deport the people at the same time.

- Manasseh and Amon (2 Kings 20:21b-21:23 and 21:25-26a)—Manasseh, son of Hezekiah, becomes the next king and completely reverses Hezekiah's religious reform, transforming the Temple of Yawheh into an interreligious shrine honoring various deities worshiped by the people of his nation. God consequently condemns him, declaring "I will wipe out Jerusalem as one wipes a dish, wiping it and turning it upside down." Manasseh is also reported to have "shed so much innocent blood that he filled Jerusalem from end to end." His reign was unusually long, 55 years. (Chronicles 33 portrays him as repenting for his sins and reversing his policy during his later reign.) After his death, his son, Amon, perpetuates the rejection of Hezekiah's reform, and refuses to repent. However, Amon becomes the victim of a conspiracy when he is killed by his own servants.

- Josiah 2 Kings 21:24, and 21:26b-23:30a—This coup results in Josiah, son of Amon, being placed on the throne of Judah at the age of eight. In the eighteenth year of his reign, the chief priest, Hilkiah, discovers a book of the law in the Temple of Jerusalem. This newly discovered book is verified as genuine by the prophetess Huldah, and the penitent Josiah vows to enact all of its command.[17] He purges the Temple of pagan altars and icons, destroys the high places, brings the scattered Yahwist priests who attend them to Jerusalem, obliterates the altar at Bethel so detested by the narrator, rids the land of mediums, and massacres priests who offer sacrifices to other gods than Yahweh. The author praises him for these acts, saying: "Neither before nor after Josiah was there a king like him who turned to the Lord as he did—-with all his heart and with all his soul and with all his strength, in accordance with all the Law of Moses." However, when this champion of Yahweh rides out to confront Pharaoh Necho II at Megiddo, (609 B.C.E.), God does not protect him; and he is slain.[18]

- Jehoahaz and Jehoiakim (2 Kings 23:30b-24:6a and 24:7)—The people appoint Jehoahaz, a son of Josiah, as the king, but Necho of Egypt imprisons Jehoahaz, and deports him. The Egyptian ruler raises another son of Josiah to the throne and changes his name to Jehoiakim. Jehoiakim taxes the people to give tribute to Necho, but the country is soon attacked by Nebuchadnezzar II, the new Babylonian king. Judah thus becomes the vassal of Babylon. However, three years later, Jehoiakim rebels, and Nebuchadnezzar sends forces to attack Judah. The account of Jehoiakim goes no further in the Book of Kings. Details of his rebellion, Nebuchadnezzar's response, and Jehoiakim's violent death at the hands of his own people can be gleaned from the Book of Jeremiah.

- Jehoiachin (2 Kings 24:6b, 24:8-12, and 25:27-30)—Jehoiachin becomes the next king, reigning only three months. Nebuchadnezzar attacks Jerusalem and besieges it, so Jehoiachin and his court surrender and the king is taken captive. Thousands of soldiers, craftsmen, and elite citizens are forced into exile.

- Zedekiah (2 Kings 24:17-25:7)—Nebuchadnezzar places Jehoiachin's uncle, Zedekiah, on the throne, but in the ninth year of his reign, Zedekiah rebels. Having lost patience with the rebellious Judah, Nebuchadnezzar besieges Jerusalem and breaches the city walls. Zedekiah flees, but is captured. He is forced to watch as his sons are killed in front of him, and then Zedekiah's eyes put out. He is bound in chains and taken to Babylon.

- The Babylonian captivity (2 Kings 24:13-16 and 25:8-21)—Once Zedekiah's rebellion is suppressed, Nebuchadnezzar sends Nebuzaradan to Jerusalem, where he tears down the walls, destroys the Temple and palace, burns the city, seizes the religious treasures of the Temple, and deports much of the population to Babylon. The two highest priests, a scribe, a leading court official, five personal servants to Zedekiah, and 60 other leading people remaining in Jerusalem, are taken to Nebuchadnezzar and killed.[19]

- The story of Gedaliah (2 Kings 25:22-26)—The few people remaining in Judah are put under the command of Gedaliah, who promises the commanders of the army of Judah that they will not be harmed as long as they remain loyal to Babylon. However, one of the commanders conspires against Gedaliah, and has him killed, but the people are so afraid of Nebuchadnezzar's reaction that almost the entire remaining population of Judah flees to Egypt. A final note adds that during the reign of Evil-Merodach (Amel-Marduk), Jehoichin, Judah's former king, was released from prison and given a place of honor at the king's table.

Authorship

The authorship, or rather compilation, of these books is uncertain. The authors themselves refer to several other works which they have apparently consulted in compiling the history of the kings:

- The "book of the acts of Solomon" (1 Kings 11:41)

- The "book of the chronicles of the kings of Judah" (14:29; 15:7, 23, etc.)

- The "book of the chronicles of the kings of Israel" (14:19; 15:31; 16:14, 20, 27, etc.).

To this, biblical scholars add the sources known as the Elijah cycle and the Elisha cycle, which have been inserted into the account, as well as materials identical to historical verses found in the Book of Jeremiah and the Book of Isaiah and various other accounts from folklore, war stories, etc.

The date of the final composition of Kings was probably some time between 561 B.C.E. (the date of the events in book's last chapter when Jehoiachin was released from captivity by Evil-Merodach)and 538 B.C.E. (the date of the decree of deliverance by Cyrus the Great).

Because some portions are almost identical to the Book of Jeremiah—for example, 2 Kings 24:18-25 and Jeremiah 52; 39:1-10; 40:7-41:10—traditionally Jeremiah (or his scribe, Baruch) was credited as the author of Kings. Another early supposition was that Ezra, after the Babylonian captivity, compiled the text from the official court chronicles of David and Solomon together with the writings of the prophets Nathan, Gad, and Iddo. However, it was more usually said that Ezra was the compiler of the Books of Chronicles, which was at one time was treated as a single book together with the Book of Ezra and the Book of Nehemiah.

The majority of textual criticism today is of the belief that the Books of Kings—together with Deuteronomy, Joshua, Judges, and Samuel—were originally compiled into a single work, the Deuteronomic history, by a single redactor, known as the Deuteronomist. Some scholars suggest the prophet Jeremiah as the Deuteronomist, while others think the high priest Hilkiah, who "found" the Book of the Law in the Temple of Jerusalem during the reign of King Josiah, is a more likely candidate. Another suggestion is that several scribes may have collaborated on the work, which was begun during Josiah's time and finished during the Babylonian exile.[20]

It was not the purpose of the compiler(s) to give a complete history of the period covered by his work, for he constantly refers to other sources for additional details. He mentions as a rule only a few important events which are sufficient to illustrate the attitude of the king toward the Deuteronomic law, or some feature of it—such as the central sanctuary, the northern altars at Dan and Bethel, the Ashera poles, and the high places—and then proceeds to pronounce judgment upon him accordingly. Each reign is introduced with a regular formula by the redactor usually including an estimate of his religious character, followed by an excerpt from one of the sources, and finally a brief summary of his death and burial (for example, compare 1 Kings 15:1-9 with 1 Kings 15:25-32). In some cases the material in the middle section is lengthy and derives from more than one source, as when stories from the Elijah cycle, military accounts, or tales of miraculous events are detailed.

Time of redaction

There are indications that imply that the first redaction of Kings must have occurred before the downfall of the Judean monarchy. For example, the phrase unto this day occurs in 1 Kings 8:8, 9:21, 12:19; 2 Kings 8:22, 16:6 describing conditions that no longer existed during the time of the Exile. Also, in 1 Kings 9:36, 15:4, and 2 Kings 8:19, which come from the hand of a Deuteronomic editor, David still has a "lamp" burning in Jerusalem; that is, the Davidic dynasty is still reigning. Finally, 1 Kings 8:29-31, 8:33, 8:35, 8:38, 8:42, 8:44, 8:48, 9:3, 11:36 imply that the Temple is still standing.

There was, accordingly, a pre-exilic Book of Kings. The work in this earlier form must have been composed between 621 and 586 B.C.E. As the glamour of Josiah's reforms deeply impressed the original compiler, perhaps he wrote before 600. To this original work 2 Kings 24:10-25:30 was added in the Exile, and perhaps 23:31-24:9 or other sections. In addition to the supplement which the exilic editor appended, a comparison of the Masoretic text with the Septuagint shows that the Hebrew version of the text was retouched by another hand after sources of the Septuagint were complete.

Textual problems

Historical problems

There a number of internal inconsistencies in the account given in Kings, as well as between the Kings' account and other versions. For example the prophet Elijah declares that Arab doom is sealed by his cooperation with Jezebel in the murder of Naboth, while the unnamed prophet who meets him earlier declares that it will result by his failure to kill the king of Aram when he had the chance. Later when the prophet Elisha inexplicably treats the captured Aramaean army to a feast instead of commanding the king of Israel to slaughter them, the Aramaens supposed do not return to harm Israel any further. But in the next chapter, they are back with a vengeance.

In addition, the account in Kings sometimes is at odd with non-biblical records, such as the Tel Dan inscription that gives credit to Hazael, not Jehu, for the deaths of Joram and Ahaziah; and the claim of Sennacherib that he conquered all of Judah and kept Hezekiah "like a bird in a cage" in Jerusalem compared the account in Kings which claims that Sennacherib's forces were decimated by an angel of God who willed 185,000 soldiers besieging Jerusalem.

Problems of dates

The chronology of Kings also has problematic areas. The duration of reigns for the kings of Judah does not correspond correctly to their supposed times of accession as compared by the narrator to the reigns of the kings of Israel. Although the references are generally useful for understanding the era in which a particular king lived, the numbers simply do not add up. Since the reigns of each king is referenced to a contemporary in his opposite kingdom, the same issue obviously applies to the kings of Israel. As a result, there are various chronologies proposed for the period by different experts.

There are also external difficulties for the dating. The king that the Book of Kings names as Ahaz is claimed within it to reign for only 16 years. However, some of the events during his reign are recorded elsewhere with a non-biblical consensus emerging that ruled between 735 B.C.E. and 715 B.C.E., a period of 20 years.

Names and identities

In the time of the Omrides (that is the descendants of Omri), there are remarkable co-incidences between the names of the kings of Judah and those of Israel. They are often identical:

- Jehoram/Joram reigned in Israel at the same time that another Jehoram was king of Judah.

- Jehoash son of Jehoahaz was king of Israel while another Jehoash/Joash son of Jehoahaz/Ahaziah was king of Judah.

As a consequence a number of scholars have proposed that this was a period in which Judah and Israel were united under one king, with the Deuteronic redactor splitting the account into two. Some also argue that the stories of Jezebel and Athaliah—two ruthless, Baal-worshiping queens who are eventually deposed with the temple of Baal being destroyed afterward—are likewise two version of the same tale. Arguing against this is the fact the families of Ahab and Jehoshaphat were closely connected and may well have given their sons the same name. Similar events are evident, for example, in the history of European royalty, in which blood relations named Henry, Philip, and William often ruled at the same time in different countries.

The name Hadad and compounds of it also occur at several locations within the text. Hadad is the name of the Canaanite deity often identical toBa'al, which means simply "lord" and was apparently used in reference to several different gods. Consequently, several kings from the region surrounding Israel and Judah had names that included the word Hadad, which has can lead to much confusion in the text:

- Hadadezer (Hadad+ezer) is an Assyrian king

- Hadad is the name of a king of Edom

- Ben-hadad is the name of at least two kings of Aram. Although this name simply means son of Hadad it does not necessarily mean that Hadad was the name of the king's father. Rather it means refers to the status of the king as the "son of (the god) Hadad and therefore divine.

- King Hadad is the name of a deity (according to the text), i.e. Hadad.

In addition, while Ba'al is often refers to Hadad, the term Baalzebub also appears as the name of a deity. Ba'alzebub, meaning lord of the flies, is most likely to be a deliberate pun, by the anti-Hadad writer, on the term Ba'alzebul, meaning prince Ba'al, i.e. Hadad. Even more confusing is the fact that some passages refer to a single king of Assyria by two different names, whereas others refer simply to the king of Assyria in several places but are actually talking about two separate historically attested kings, not the same individual.

This problem is compounded in the names of Israelite and Judahite kings, where theophoric suffixes and prefixes[21] exist in several forms related to both El and Yah/Yahweh: Ja… , Jeho… , …iah, …el, and El…. In some cases double theophory occurred, as for example in the name of the king of Judah that contemporary cuneiform inscriptions record as Jeconiah (Je+Con+Iah), which the Book of Jeremiah drops one of the theophories to make the name simply Choniah (Chon+Iah), while the Book of Kings makes his name Jehoiachin (Jeho+Iah+chin). Similarly, theophory was often flexible as to which end of names it occurred at for a single individual, so that the king of Judah which the Book of Kings names as Ahaziah (Ahaz + iah) is named by the Book of Chronicles as Jehoahaz (Jeho + ahaz). Thus Ahaziah is actually the same names as Johoahaz, and since with the theophoric element dropped it would also be the same name as that of the later king referred to as Ahaz (just as Dan is the same name as Daniel with the theophoric element omitted).

Notes

- ↑ Critical scholars point out, however, that Solomon is mentioned in no historical records outside the Bible, in contrast to many other rulers of that period. Most are agreed that the glories of his reign and the extent of his realm are highly exaggerated.

- ↑ Archaeologists such as Israel Finkelstein believe that these improvements were actually from a later period, and were carried out by northern rulers, probably either Omri or Ahab.

- ↑ The tribe of Simeon had been absorbed by Judah by this time, leaving ten tribes to the north and only Judah in the south.

- ↑ The term is actually asherim, which probably means "ashera pole," a sacred pillar that may have been devoted to any number of deities, including Yahweh.

- ↑ Because the stories of Elisha and Elijah are so parallel, indeed sometimes identical, it may be that in the original version, Elijah indeed anointed Hazael and Jehu.

- ↑ The story seems at odds with the previous one, in which the cause of Ahab's doom is not Naboth's murder but Ahab's failure to kill Ben-Hadad. This provides additional evidence of more than one source being woven together in the narrative.

- ↑ Court prophets were often suspected of giving the king information that pleased him. However some court prophets, such as Nathan and Isaiah, were perfectly capable of speaking "truth to power."

- ↑ Jehoshaphat also arranged for his son Jehoram to marry Ahab's daughter, Athaliah.

- ↑ The reason for Israel's withdrawal—either horror on the part of the Israelites or a morale boost on the part of the Moabites—is unclear.

- ↑ The story, which does not mention the names of the kings involved, is apparently a legend about Elisha originally independent of the material that now follows it.

- ↑ He is called Jehoahaz is Chronicles to distinguish him from Ahaziah of Israel (both names contain the word Ahaz and the theophoric "Ya"—one as a suffix, the other as a prefix).

- ↑ In the Tel Dan Stele, Hazael apparently claims that it was he, not Jehu, who was responsible for killing Joram and Ahaziah. To stave off Hazael, Jehu became of vassal of Shalmaneser III of Assyria, to whom he is portrayed as prostrating himself, on the Black Obelisk.

- ↑ The deliverer is not named. Some suggest an Assyrian king as the most likely candidate; others believe him to have been an Israelite military hero, or possibly Joash of Judah.

- ↑ His name is actually the same as Joash of Judah.

- ↑ In ancient times, the Israelite patriarchs established sacred pillars to Yahweh and El in places such as Gilgal, Bethel, Mount Sinai, etc., but the Book of Deuteronomy, thought to be written considerably later, banned this practice, referring to sacred pillars as "asherim," regardless of the deity to which they were devoted.

- ↑ Sennacherib's own account says nothing of an angel of the incident boasts of having conquered all of Judah and keeping Hezekiah was "locked up like a caged bird," forcing him into becoming a tributary to Sennacherib.

- ↑ Most scholars, both critical and apologetic, view the book as an early version of Deuteronomy, for which reason Josiah's reform is often referred to as the Deuteronomic reform).

- ↑ The authors explain this on the basis of Yahweh's having already decided to punish Judah as a result of the sin of Josiah's grandfather Manasseh.

- ↑ A notable exception to this slaughter was the prophet Jeremiah, who had opposed the royal policy of rebellion against Babylon.

- ↑ Finkelstein (2006), for example, sees much of the Deuteronomic history as intended to justify Josiah's reforms and his policy to expand Judah's influence northward, ultimately including his campaign against Necho at Megiddo. The death of Josiah, in this view, must have come as a tremendous shock to those who saw him as a new Joshua and the greatest king since David.

- ↑ Theophory, literally, bearing a deity, refers to names honoring a particular god by including a form of the deity's name in a person's name.

References

ISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Abright, William F. The Archeology of Palestine, Magnolia, MA: Peter Smith Pub Inc; 2nd edition, 1985. ISBN 0844600032

- Bright, John. A History of Israel, Louisville KY: Westminster John Knox Press; 4th edition, 2000. ISBN 0664220681

- Dever, William G. What Did the Biblical Writers Know and When Did They Know It?: What Archaeology Can Tell Us About the Reality of Ancient Israel. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Company, 2002. ISBN 978-0802821263

- Finkelstein, Israel. David and Solomon: In Search of the Bible's Sacred Kings and the Roots of the Western Tradition. Free Press, 2006. ISBN 0743243625

- Galil, Gershon. The Chronology of the Kings of Israel and Judah, Leiden: Brill Academic Publishers, 1996. ISBN 9004106111

- Grant, Michael. The History of Ancient Israel, NY: Charles Srcibner's Sons, 1984. ISBN 0684180812

- Keller, Werner. The Bible as History, NY: Bantam, 1983. ISBN 0553279432

- Mazar, Amihai. Archaeology of the Land of the Bible-10,000-586 B.C.E., Doubleday, 1990. ISBN 038523970X

- Miller, J. Maxwell. A History of Ancient Israel and Judah, Louisville KY: Westminster John Knox Press, 1986. ISBN 066421262X

External links

All links retrieved November 27, 2018.

- 2 Kings Chapter 1. Jewish Publication Society.

- Translation with Rashi's commentary. www.Chabad.org.

- King James Version. www.gospelhall.org.

- Books of Kings. www.jewishencyclopedia.com.

|

|||||||||||||||||

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.

↧ Download as ZWI file | Last modified: 02/03/2023 22:53:44 | 164 views

☰ Source: https://www.newworldencyclopedia.org/entry/Books_of_Kings | License: CC BY-SA 3.0

ZWI signed:

ZWI signed:

KSF

KSF