Wigwam

From Nwe

From Nwe

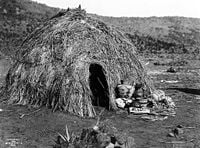

A wigwam or wickiup is a domed single-room dwelling used by certain Native American tribes. The term wickiup is generally used to label these kinds of dwellings in American Southwest and West. Wigwam is usually applied to these structures in the American Northeast.

The use of these terms by non-Native Americans has been somewhat arbitrary, often used to refer to many distinct types of Native American structures regardless of location or cultural group. The wigwam should not to be confused with the Plains Indians' tipi, which has a very different construction, structure, and use. In the twenty-first century, the term "wickiup" became preferred for this structure due to the overuse of the term "wigwam" and the perception of it as part of the stereotype of "uncivilized" American Indians.

In fact, the wickiup had a rather sophisticated construction and reveals the creativity of the people who used it. Semi-permanent, unlike the portable tipi which was also used by many of the same tribes during hunting trips, the wickiup is constructed from available natural items and provides shelter from all types of weather: It provides shade from the sun during summer and can be open to provide ventilation; it also can be waterproofed and lined to keep the inhabitants warm and dry. These structures are also commonly used for sweat lodge ceremonies, continuing into contemporary times.

Etymology

The term wigwam derives from Algonquian languages, where wik- or wig- is the root meaning "to dwell." Thus wikuwam in Eastern Wabenaki (Maliseet), wigwôm in Western Wabenaki (Abenaki language), and wigiwaam in the Anishinaabe languages are all terms meaning "their dwelling." Wickiup derives from the Fox dialect variation wikiyap or wikiyapi.

Mary Rowlandson (1682) used the term "wigwam" in reference to the dwelling places of the Narragansett Native Americans that she stayed with while in their captivity during King Philip's War in 1675. Since that time, the term "wigwam" has remained in common English usage as a synonym for any "Indian house." However this usage is incorrect as there are significant differences between the wigwam, the tipi, and other native forms of housing. Consequently, in the twenty-first century the term "wickiup" has been favored by many tribes to avoid the stereotypical connotations of the overused term "wigwam."

Construction

The wigwam, typical of Algonquian tribes of the Northeast, or wickiup, typical of southwestern tribes such as the Apache, are domed dwellings. Their structure is formed with a frame of arched poles, most often wooden, which are covered with some sort of roofing material. Details of construction vary with the culture and local availability of materials. Some of the roofing materials used include grass, brush, bark, rushes, mats, reeds, hides, and cloth.

Use

The wigwam or wickiup was the typical dwelling of many Native American tribes. These domed, round shelters have been used for centuries by many different Native American cultures. Their curved surfaces make them ideal shelters for all kinds of conditions.

A wickiup was used in semi-permanent camps and the rather sophisticated construction lasted well in either summer or winter. Its domed structure offered sufficient protection from cold when covered in animal hides, or shade from the sun in the summer. Many tribes who spent part of the year traveling greater distances for hunting used the more portable tipis for those trips, returning to villages of wickiups when the hunt was over.

Sweat lodge

The sweat lodge is a ceremonial sauna used by a number of North American First Nations and Native American peoples. Wickiup style huts are often used, although even a simple hole dug into the ground and covered with planks or tree trunks may suffice for some tribes. The ceremony involves heating stones, typically in an exterior fire and then placing them in a central pit in the ground (Clark 2003). Often the stones are granite and they glow red in the dark lodge.

Placement and orientation of the lodge within its environment often facilitates the ceremony's connection with the spirit world. The lodge may be oriented within its environment for a specific purpose; for example, a lodge constructed near a lake could be run with the intention of connecting to the spirit of the lake. Participants enter the lodge and carry out various rituals, such as prayers, drumming, and offerings to the spirit world. While in the lodge the hot rocks raise the temperature so that participants sweat profusely. Purification of body, mind, and spirit are the major purposes and benefits resulting from sweat lodge use.

This use of the wickiup for sweat lodge rituals continues in contemporary times, while more European style houses have mostly replaced them for living purposes.

Variations

Wigwams of Northeast

Wigwams are most often seasonal structures although the term is applied to structures built by Native American groups that are more permanent. Wigwams usually take longer to put up than tipis and their frames are usually not portable like those of a tipi.

A typical wigwam in the Northeast has a curved surface which can hold up against the worst weather.

The man of the family was responsible for the framing of the wigwam. Young green tree saplings, of just about any type of wood, about 10 feet (3.0 m) to 15 feet (4.6 m) long were cut down. These tree saplings were then bent by stretching the wood. While these saplings were being bent, a circle was drawn on the ground. The diameter of the circle varied from 10 feet (3.0 m) to 16 feet (4.9 m). The bent saplings were then placed over the drawn circle, using the tallest saplings in the middle and the shorter ones on the outside. The saplings formed arches all in one direction on the circle. The next set of saplings was used to wrap around the wigwam to give the shelter support. When the two sets of saplings were finally tied together, the sides and roof were placed on it. The sides of the wigwam were usually made of bark stripped from trees. Mats of woven rushes could also be used for the roof and sides.

Wickiups of Southwest and West

The regional non-Native American term for a single room dome-like dwelling is "wickiup." There is a great deal of variation in size, shape, and materials. A distinction is made between a wickiup and a tipi, a Navajo hogan, or a Puebloan kiva.

The Paiute, like other nomadic tribes of the Great Basin area, slept in domed, round shelters known as wickiups or Kahn. The curved surfaces made them ideal shelters for all kinds of conditions; an escape from the sun during summer, and when lined with bark they were safe and warm in winter. They built these dwellings in different locations as they moved throughout their territory. Since all their daily activities took place outside, including making fires for cooking or warmth, the shelters were primarily used for sleeping.

Following is a description of Chiricahua wickiups recorded by anthropologist Morris Opler:

The home in which the family lives is made by the men and is ordinarily a circular, dome-shaped brush dwelling, with the floor at ground level. It is eight feet high at the center and approximately seven feet in diameter. To build it, long fresh poles of oak or willow are driven into the ground or placed in holes made with a digging stick. These poles, which form the framework, are arranged at one-foot intervals and are bound together at the top with yucca-leaf strands. Over them a thatching of bundles of big bluestem grass or bear grass is tied, shingle style, with yucca strings. A smoke hole opens above a central fireplace. A hide, suspended at the entrance, is fixed on a cross-beam so that it may be swung forward or backward. The doorway may face in any direction. For waterproofing, pieces of hide are thrown over the outer hatching, and in rainy weather, if a fire is not needed, even the smoke hole is covered. In warm, dry weather much of the outer roofing is stripped off. It takes approximately three days to erect a sturdy dwelling of this type. These houses are 'warm and comfortable, even though there is a big snow.' The interior is lined with brush and grass beds over which robes are spread (Opler 1996, 22-23).

The woman not only makes the furnishings of the home but is responsible for the construction, maintenance, and repair of the dwelling itself and for the arrangement of everything in it. She provides the grass and brush beds and replaces them when they become too old and dry…. However, formerly 'they had no permanent homes, so they didn't bother with cleaning.' Said a Central Chiricahua informant:

- Both the tipi and the oval-shaped house were used when I was a boy. The oval hut was covered with hide and was the best house. The more well-to-do had this kind. The tepee type was just made of brush. It had a place for a fire in the center. It was just thrown together. Both types were common even before my time. (Opler 1996, 385-386)

References

ISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Clark, Ella E. 2003. Indian Legends of the Pacific Northwest. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press. ISBN 0520239261

- Opler, Morris E. [1941] 1996. An Apache Life-way: The Economic, Social, and Religious Institutions of the Chiricahua Indians. reprint ed. Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 0803286104

- Rowlandson, Mary White. [1682] 2006. Narrative of the Captivity and Restoration of Mrs. Mary Rowlandson. Hard Press. ISBN 1406944017

- Waldman, Carl. 2006. Encyclopedia of Native American Tribes. New York, NY: Checkmark Books. ISBN 978-0816062744.

- Zimmerman, Larry J., and Brian Leigh Molyneaux. 2000. Native North America. Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 0806132868

External links

All links retrieved October 2, 2020.

|

|||||

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.

↧ Download as ZWI file | Last modified: 02/03/2023 22:09:20 | 7 views

☰ Source: https://www.newworldencyclopedia.org/entry/Wickiup | License: CC BY-SA 3.0

ZWI signed:

ZWI signed:

KSF

KSF