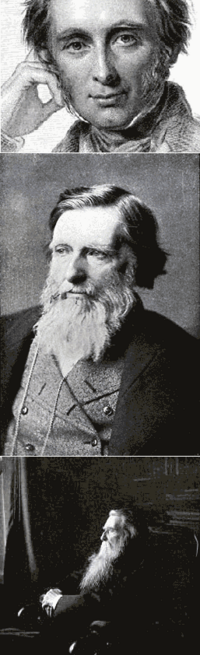

John Ruskin

From Nwe

From Nwe

Middle: Ruskin in middle-age, as Slade Professor of Art at Oxford (1869-1879). Scanned from 1879 book.

Bottom: John Ruskin in old age, 1894, by photographer Frederick Hollyer. 1894 print. All public domain.

John Ruskin (February 8, 1819 – January 20, 1900) is best known for his work as an art critic and social critic, but is remembered as an author, poet, and artist as well. Ruskin's essays on art and architecture were extremely influential in the Victorian and Edwardian eras. Ruskin is also known for his advocacy of "Christian socialism." He attacked laissez faire economics because it failed to acknowledge the complexities of human desires and motivations. He argued that the state should intervene to regulate the economy in the service of such higher values. Ruskin's "Christian socialism" was an attempt to integrate the values of Christianity into the realm of economics.

Life

Ruskin was born in London, and raised in south London, the son of a wine importer who was one of the founders of the company that became Allied Domecq. He was educated at home, and entered the University of Oxford without proper qualifications for a degree. Nevertheless, he impressed the scholars of Christ Church, Oxford, after he won the Newdigate prize for poetry, his earliest interest. In consequence, he was awarded a degree.

He published his first book, Modern Painters, in 1843, under the anonymous identity "An Oxford Graduate." It argued that modern landscape painters—in particular J.M.W. Turner—were superior to the so-called "Old Masters" of the Renaissance. Such a claim was highly controversial, especially as Turner's semi-abstract late works were being denounced as meaningless daubs. Ruskin argued that these works derived from Turner's profound understanding of nature. He soon met and befriended Turner, eventually becoming one of the executors of his will.

Ruskin followed this book with a second volume, developing his ideas about symbolism in art. He then turned to architecture, writing The Seven Lamps of Architecture and The Stones of Venice, both of which argued that architecture cannot be separated from morality, and that the "Decorated Gothic" style was the highest form of architecture yet achieved.[1]

By this time, Ruskin was writing in his own name, and had become the most famous cultural theorist of his day. In 1848, he married Effie Gray, for whom he wrote the early fantasy novel The King of the Golden River. Their marriage was notoriously unhappy, eventually being annulled in 1854, on grounds of his "incurable impotency,"[2] a charge Ruskin later disputed. Effie later married the artist John Everett Millais, who had been Ruskin's protegé.

Ruskin had come into contact with Millais following the controversy over his painting, Christ in the House of his Parents, which was considered blasphemous at the time. Millais, with his colleagues William Holman Hunt and Dante Gabriel Rossetti, had established the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood in 1848. The Pre-Raphaelites were influenced by Ruskin's theories. As a result, the critic wrote letters to The Times defending their work, later meeting them. Initially, he favored Millais, who traveled to Scotland with Ruskin and Effie to paint Ruskin's portrait. Effie's increasing attachment to Millais created a crisis in the marriage, leading Effie to leave Ruskin, causing a major public scandal. Millais abandoned the Pre-Raphaelite style after his marriage, and his later works were often savagely attacked by Ruskin. Ruskin continued to support Hunt and Rossetti. He also provided independent funds to encourage the art of Rossetti's wife Elizabeth Siddal. Other artists influenced by the Pre-Raphaelites also received both written and financial support from him, including John Brett, Edward Burne-Jones, and John William Inchbold.

During this period, Ruskin wrote regular reviews of the annual exhibitions at the Royal Academy under the title Academy Notes. His reviews were so influential and so judgmental that he alienated many artists, leading to much comment. For example Punch published a comic poem about a victim of the critic, containing the lines "I paints and paints, hears no complaints…then savage Ruskin sticks his tusk in and nobody will buy."

Ruskin also sought to encourage the creation of architecture based on his theories. He was friendly with Sir Henry Acland, who supported his attempts to get the new Oxford University Museum of Natural History built as a model of modern Gothic. Ruskin also inspired other architects to adapt the Gothic style for modern culture. These buildings created what has been called a distinctive "Ruskinian Gothic" style.[3]

Following a crisis of religious belief, Ruskin abandoned art criticism at the end of the 1850s, moving towards commentary on politics, under the influence of his great friend, Thomas Carlyle. In Unto This Last, he expounded his theories about social justice, which influenced the development of the British Labor party and of Christian socialism. Upon the death of his father, Ruskin declared that it was not possible to be a rich socialist and gave away most of his inheritance. He founded the charity known as the Guild of St George in the 1870s, and endowed it with large sums of money as well as a remarkable collection of art. He also gave the money to enable Octavia Hill to begin her practical campaign of housing reform. He attempted to reach a wide readership with his pamphlets, Fors Clavigera, aimed at the "working men of England." He also taught at the Working Men's College, London, and was the first Slade Professor of Fine Art at Oxford, from 1869 to 1879, and he also served a second term. Ruskin College, Oxford is named after him.

While at Oxford, Ruskin became friendly with Lewis Carroll, another don, and was photographed by him. After the parting of Carroll and Alice Liddell, she and her sisters pursued a similar relationship with Ruskin, as detailed in Ruskin's autobiography Praeterita.

During this period Ruskin fell deeply in love with Rose la Touche, an intensely religious young woman. He met her in 1858, when she was only nine years old, proposed to her eight years later, and was finally rejected in 1872. She died shortly afterwards. These events plunged Ruskin into despair and led to bouts of mental illness. He suffered from a number of breakdowns as well as delirious visions.

In 1878, he published a scathing review of paintings by James McNeill Whistler exhibited at the Grosvenor Gallery. He found particular fault with Nocturne in Black and Gold: The Falling Rocket, and accused Whistler of "ask[ing] two hundred guineas for throwing a pot of paint in the public's face."[4] Attempting to gain publicity, Whistler filed, and won, a libel suit against Ruskin, though the award of damages was only one farthing. The episode tarnished Ruskin's reputation, and may have accelerated his mental decline.

The emergence of the Aesthetic movement and Impressionism alienated Ruskin from the art world, and his later writings were increasingly seen as irrelevant, especially as he seemed to be more interested in book illustrators such as Kate Greenaway than in modern art. He continued to support philanthropic movements such as the Home Arts and Industries Association

Much of his later life was spent at a house called Brantwood, on the shores of Coniston Water located in the Lake District of England.

Work

Ruskin's range was vast. He wrote over 250 works which started from art history, but expanded to cover topics ranging over science, geology, ornithology, literary criticism, the environmental effects of pollution, and mythology. After his death, Ruskin's works were collected together in a massive "library edition," completed in 1912, by his friends Edward Cook and Alexander Wedderburn. Its index is famously elaborate, attempting to articulate the complex interconnectedness of his thought.

Art and design

Ruskin's early work in defense of Turner was based on his belief that art was essentially concerned to communicate an understanding of nature, and that authentic artists should reject inherited conventions in order to appreciate and study effects of form and color by direct observation. His most famous dictum was "go to nature in all singleness of heart, rejecting nothing and selecting nothing." He later believed that the Pre-Raphaelites formed "a new and noble school" of art that would provide the basis for a thoroughgoing reform of the art world. For Ruskin, art should communicate truth above all things. However, he believed that this was not revealed by mere display of skill, but the expression of the artist's whole moral outlook. Ruskin rejected the work of Whistler because he considered it to epitomize a reductive mechanization of art.

Rejection of mechanization and standardization also informed Ruskin's theories of architecture. For Ruskin, the Gothic style embodied the same moral truths that he sought in great art. It expressed the meaning of architecture—as a combination of the values of strength, solidity, and aspiration; all written, as it were, in stone. For Ruskin, true Gothic architecture involved the whole community in its creation, and expressed the full range of human emotions, from the sublime effects of soaring spires to the comically ridiculous carved grotesques and gargoyles. Even its crude and "savage" aspects were proof of "the liberty of every workman who struck the stone; a freedom of thought, and rank in scale of being, such as no laws, no charters, no charities can secure."[5] Classical architecture, in contrast, expressed a morally vacuous repressive standardization. Ruskin associated Classical values with modern developments, in particular with the demoralizing consequences of the industrial revolution, resulting in buildings such as The Crystal Palace, which he despised as an over-sized greenhouse. Although Ruskin wrote about architecture in many works over the course of his career, his much-anthologized essay, "The Nature of Gothic," from the second volume of The Stones of Venice (1853) is widely considered to be one of his most important and evocative discussions of his central argument.

These views led to his later works attacking laissez faire capitalism, which influenced many trade union leaders of the Victorian era. He was also the inspiration for the [[Arts and Crafts Movement[[, the founding of the National Trust for Places of Historic Interest or Natural Beauty, the National Art Collections Fund, and the Society for the Protection of Ancient Buildings.

Ruskin's views on art, wrote Kenneth Clark, "cannot be made to form a logical system, and perhaps owe to this fact a part of their value." Certain principles, however, remain consistent throughout his work and have been summarized in Clark's own words as the following:

- That art is not a matter of taste, but involves the whole man. Whether in making or perceiving a work of art, we bring to bear on it feeling, intellect, morals, knowledge, memory, and every other human capacity, all focused in a flash on a single point. Aesthetic man is a concept as false and dehumanizing as economic man.

- That even the most superior mind and the most powerful imagination must found itself on facts, which must be recognized for what they are. The imagination will often reshape them in a way which the prosaic mind cannot understand; but this recreation will be based on facts, not on formulas or illusions.

- That these facts must be perceived by the senses, or felt; not learnt.

- That the greatest artists and schools of art have believed it their duty to impart vital truths, not only about the facts of vision, but about religion and the conduct of life.

- That beauty of form is revealed in organisms which have developed perfectly according to their laws of growth, and so give, in his own words, "the appearance of felicitous fulfillment of function."

- That this fulfilment of function depends on all parts of an organism cohering and cooperating. This was what he called the "Law of Help," one of Ruskin's fundamental beliefs, extending from nature and art to society.

- That good art is done with enjoyment. The artist must feel that, within certain reasonable limits, he is free, that he is wanted by society, and that the ideas he is asked to express are true and important.

- That great art is the expression of epochs where people are united by a common faith and a common purpose, accept their laws, believe in their leaders, and take a serious view of human destiny.[6]

Social theory

Ruskin's pioneering of the ideas that led to the Arts and Crafts movement was related to the growth of Christian socialism, an ideology that he helped to formulate in his book, Unto This Last, in which he attacked laissez faire economics because it failed to acknowledge the complexities of human desires and motivations. He argued that the State should intervene to regulate the economy in the service of such higher values. These ideas were closely related to those of Thomas Carlyle, but whereas Carlyle emphasized the need for strong leadership, Ruskin emphasised what later evolved into the concept of "social economy"—networks of charitable, co-operative, and other non-governmental organizations.

Legacy

Ruskin's influence extends far beyond the field of art history. The author Leo Tolstoy described him as "one of those rare men who think with their heart." Marcel Proust was a Ruskin enthusiast and translated his works into French. Mahatma Gandhi said that Ruskin had been the single greatest influence in his life. Ruskin's views also attracted Oscar Wilde's imagination in the late nineteenth century.

A number of utopian socialist "Ruskin Colonies" were created in attempts to put his political ideals into practice. These included the founders of Ruskin, Nebraska, Ruskin, British Columbia, and the Ruskin Commonwealth Association, a colony which existed in Dickson County, Tennessee, from 1894 to 1899. Ruskin's ideas also influenced the development of the British Labour Party.

Biographies

The defining work on Ruskin for the twentieth century was The Darkening Glass (Columbia UP, 1960) by Columbia professor John D. Rosenberg, backed by his ubiquitous paperback anthology, The Genius of John Ruskin (1963). Neither book has ever been out of print. Rosenberg, who began teaching at Columbia in 1963, and was still teaching in 2006, produced countless Ruskinians who are now the Victorianists at various American universities.

A definitive two-volume biography by Tim Hilton appeared as, John Ruskin: The Early Years (Yale University Press, 1985) and John Ruskin: The Later Years (Yale University Press, 2000).

Controversies

Turner erotic drawings

Until 2005, biographies of both J.M.W. Turner and Ruskin had claimed that in 1858, Ruskin burned bundles of erotic paintings and drawings by Turner, in order to protect Turner's posthumous reputation. In 2005, these same works by Turner were discovered in a neglected British archive, proving that Ruskin did not destroy them.[7]

Sexuality

Ruskin's sexuality has led to much speculation and critical comment. His one marriage, to Effie Gray, was annulled after six years because of non-consummation. His wife, in a letter to her parents, claimed that he found her "person" (meaning her body) repugnant. "He alleged various reasons, hatred to children, religious motives, a desire to preserve my beauty, and finally this last year he told me his true reason… that he had imagined women were quite different to what he saw I was, and that the reason he did not make me his Wife was because he was disgusted with my person the first evening 10th April." Ruskin confirmed this in his statement to his lawyer during the annulment proceedings. "It may be thought strange that I could abstain from a woman who to most people was so attractive. But though her face was beautiful, her person was not formed to excite passion. On the contrary, there were certain circumstances in her person which completely checked it."[8]

The cause of this mysterious "disgust" has led to much speculation. Ruskin's biographer, Mary Luytens, suggested that he rejected Effie because he was horrified by the sight of her pubic hair. Luytens argued that Ruskin must have known the female form only through Greek statues and paintings of the nude lacking pubic hair and found the reality shocking.[9] This speculation has been repeated by later biographers and essayists and it is now something that "everyone knows" about Ruskin. However, there is no proof for this, and some disagree. Peter Fuller, in his book, Theoria: Art and the Absence of Grace, writes, "It has been said that he was frightened on the wedding night by the sight of his wife's pubic hair; more probably, he was perturbed by her menstrual blood." Ruskin's biographers Tim Hilton and John Batchelor also take the view that menstruation is the more likely explanation, though Bachelor also suggests that body-odor may have been the problem.

Ruskin's later relationship with Rose la Touche has also led to claims that he had paedophilic inclinations, on the grounds that he stated that he fell in love with her when he met her at the age of nine.[10] In fact, he did not approach her as a suitor until she was seventeen, and he repeatedly proposed to her for as long as she lived. Ruskin is not known to have had any other romantic liaisons or sexual intimacies. However, during an episode of mental derangement he wrote a letter in which he insisted that Rose's spirit had instructed him to marry a girl who was visiting him at the time.[11]

Letters from Ruskin to Kate Greenaway survive in which he repeatedly asks her to draw her "girlies" (as he called her child figures) without clothing.[12]

Ruskin's biographers disagree about the allegation of paedophilia. Hilton, in his two-volume biography, baldly asserts that "he was a paedophile," while Bachelor argues that the term is inappropriate because his behavior does not "fit the profile".[13]

Definitions

Ruskin coined quite a few distinctive terms, some of which were collected by the Nuttall Encyclopedia. Some include:

- Pathetic Fallacy: A term he invented to describe the ascription of human emotions to impersonal natural forces, as in phrases like "the wind sighed."

- Fors Clavigera: The name given by Ruskin to a series of letters to workmen, written during the seventies of the nineteenth century, and employed by him to designate three great powers which go to fashion human destiny, viz., Force, wearing, as it were, (clava) the club of Hercules; Fortitude, wearing, as it were, (clavis) the key of Ulysses; and Fortune, wearing, as it were, (clavus) the nail of Lycurgus. That is to say, Faculty waiting on the right moment, and then striking in.

- Modern Atheism: Ascribed by Ruskin to "the unfortunate persistence of the clergy in teaching children what they cannot understand, and in employing young consecrate persons to assert in pulpits what they do not know."

- The Want of England: "England needs," says Ruskin, "examples of people who, leaving Heaven to decide whether they are to rise in the world, decide for themselves that they will be happy in it, and have resolved to seek, not greater wealth, but simpler pleasures; not higher fortune, but deeper felicity; making the first of possessions self-possession, and honoring themselves in the harmless pride and calm pursuits of peace."

Partial bibliography

- Poems (1835-1846)

- The Poetry of Architecture: Cottage, Villa, etc., to Which Is Added Suggestions on Works of Art (1837-1838)

- The King of the Golden River, or The Black Brothers (1841)

- Modern Painters

- Part I. Of General Principles (1843-1844)

- Part II. Of Truth (1843-1846)

- Part III. Of Ideas of Beauty (1846)

- Part IV. Of Many Things (1856)

- Part V. Mountain Beauty (1856)

- Part VI. Of Leaf Beauty (1860)

- Part VII. Of Cloud Beauty (1860)

- Part VIII. Of Ideas of Relation: I. Of Invention Formal (1860)

- Part IX. Of Ideas of Relation: II. Of Invention Spiritual (1860)

- Review of Lord Lindsay's "Sketches of the History of Christian Art" (1847)

- The Seven Lamps of Architecture (1849)

- Letters to the Times in Defense of Hunt and Millais (1851)

- Pre-Raphaelitism (1851)

- The Stones of Venice

- Volume I. The Foundations (1851)

- Volume II. The Sea–Stories (1853)

- Volume III. The Fall (1853)

- Lectures on Architecture and Poetry, Delivered at Edinburgh, in November, 1853

- Architecture and Painting (1854)

- Letters to the Times in Defense of Pre-Raphaelite Painting (1854)

- Academy Notes: Annual Reviews of the June Royal Academy Exhibitions (1855-1859 / 1875)

- The Harbours of England (1856)

- "A Joy Forever" and Its Price in the Market, or The Political Economy of Art (1857 / 1880)

- The Elements of Drawing, in Three Letters to Beginners (1857)

- The Two Paths: Being Lectures on Art, and Its Application to Decoration and Manufacture, Delivered in 1858–9

- The Elements of Perspective, Arranged for the Use of Schools and Intended to be Read in Connection with the First Three Books of Euclid (1859)

- "Unto This Last": Four Essays on the First Principles of Political Economy (1860)

- Munera Pulveris: Essays on Political Economy (1862-1863 / 1872)

- Cestus of Aglaia (1864)

- Sesame and Lilies (1864-1865)

- The Ethics of the Dust: Ten Lectures to Little Housewives on the Elements of Chrystallisation (1866)

- The Crown of Wild Olive: Three Lectures on Work, Traffic and War (1866)

- Time and Tide by Weare and Tyne: Twenty-five Letters to a Working Man of Sunderland on the Laws of Work (1867)

- The Flamboyant Architecture of the Somme (1869)

- The Queen of the Air: Being a Study of the Greek Myths of Cloud and Storm (1869)

- Verona and its Rivers (1870)

- Lectures on Art, Delivered before the University of Oxford in Hilary Term, 1870

- Aratra Pentelici: Six Lectures on the Elements of Sculpture Given before the University of Oxford in Michaelmas Term, 1870

- Lectures on Sculpture, Delivered at Oxford, 1870–1871

- Fors Clavigera: Letters to the Workmen and Labourers of Great Britain

- Volume I. (1871)

- Volume II.

- Volume III.

- Volume IV. (1880)

- The Eagle's Nest: Ten Lectures on the Relation of Natural Science to Art, Given before the University of Oxford in Lent Term, 1872

- Love's Meinie (1873)

- Ariadne Florentia: Six Lectures on Wood and Metal Engraving, with Appendix, Given before the University of Oxford, in Michaelmas Term, 1872

- Val d’Arno: Ten Lectures on the Tuscan Art antecedent to the Florentine Year of Victories, given before the University of Oxford in Michaelmas Term, 1872

- Mornings in Florence (1877)

- Pearls for Young Ladies (1878)

- Review of Paintings by James McNeill Whistler (1878)

- Fiction, Fair and Foul (1880)

- Deucalion: Collected Studies of the Lapse of Waves and Life of Stones (1883)

- The Art of England: Lectures Given at the University of Oxford (1883-1884)

- St Mark's Rest (1884)

- The Storm-Cloud of the Nineteenth Century (1884)

- The Pleasures of England: Lectures Given at the University of Oxford (1884-1885)

- Bible of Amiens (1885)

- Proserpina: Studies of Wayside Flowers while the Air was Yet Pure among the Alps and in the Scotland and England Which My Father Knew (1886)

- Præterita: Outlines of Scenes and Thoughts Perhaps Worthy of Memory in My Past Life (1885-1889)

- Dilecta

- Giotto and His Works in Padua: Being an Explanatory Notice of the Series of Woodcuts Executed for the Arundel Society after the Frescoes in the Arena Chapel

- Hortus Inclusus

- In Montibus Sanctis—Cœli Enarrant: Notes on Various Pictures

- An Inquiry into Some of the Conditions at Present Affecting "The Study of Architecture" in our Schools

Fictional portrayals of Ruskin

Aspects of Ruskin's life have been dramatized or incorporated into works of fiction on several occasions. Most of these concentrate on his marriage. Examples include:

- The Love of John Ruskin (1912) a silent movie about Ruskin, Effie, and Millais.

- The Passion of John Ruskin (1994), a film directed by Alex Chappel, starring Mark McKinney (Ruskin), Neve Campbell (Rose la Touche) and Colette Stevenson (Effie).

- "Modern Painters" (opera) (1995) an opera about Ruskin and Effie.

- The Invention of Truth (1995), a novel written by Marta Morazzoni in which Ruskin makes his last visit to Amiens cathedral in 1879.

- The Steampunk Trilogy (1997) by Paul Di Filippo includes a brief reference to John Ruskin in the short story "Victoria."

- The Order of Release (1998), a radio play by Robin Brooks about Ruskin, Effie and Millais

- The Invention of Love by Tom Stoppard (1998) is mainly about A. E. Housman, but Ruskin appears.

- The Countess (2000), a play written by Gregory Murphy, dealing with Ruskin's marriage.

Notes

- ↑ Trinity College, Jonathan Smith, Architecture and Induction: Whewell and Ruskin on Gothic A talk presented at "Science and British Culture in the 1830s," Trinity College, Cambridge, July 1994. Retrieved March 3, 2008.

- ↑ Sir William James, The Order of Release, the Story of John Ruskin, Effie Gray and John Everett Millais (1946), p. 237.

- ↑ J. Mordaunt Crook, "Ruskinian Gothic," in The Ruskin Polygon: Essays on the Imagination of John Ruskin (Manchester: Manchester UP, 1982), 65-93.

- ↑ Wendy Steiner, Linda Merrill, A Pot of Paint: Aesthetics on Trial in Whistler v. Ruskin—book review, Art in America. Retrieved March 3, 2008.

- ↑ John Unrau, "Ruskin, the Workman and the Savageness of Gothic," in New Approaches to Ruskin, ed Robert Hewisson (1981), p. 33-50.

- ↑ Kenneth Clark, "A Note on Ruskin's Writings on Art and Architecture," from Ruskin Today (1964).

- ↑ The Guardian, Discovery of Turner's drawings. Retrieved March 3, 2008.

- ↑ M. Lutyens, Millais and the Ruskins, p. 191.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ The Guardian, Review of Bachelor, J., John Ruskin: No Wealth but Life. Retrieved March 3, 2008.

- ↑ T. Hilton, John Ruskin: The Later Years, p. 553.

- ↑ Alison Lurie, Don't Tell the Grown-Ups: The Subversive Power of Children's Literature.

- ↑ T. Hilton, John Ruskin: A Life.

References

ISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Crook, J. Mordaunt. "Ruskinian Gothic." In The Ruskin Polygon: Essays on the Imagination of John Ruskin. Ed. John Dixon Hunt and Faith M. Holland. Manchester: Manchester UP, 1982.

- James, Sir William. The Order of Release, the Story of John Ruskin, Effie Gray, and John Everett Millais. London: John Murray, 1946.

- Lutyens, Mary. Millais and the Ruskins. London: John Murray, 1967.

External links

All links retrieved August 3, 2022.

- Ruskin Museum (Coniston).

- Ruskin's house.

- Works by John Ruskin. Project Gutenberg.

- The New Path The New Path (May, 1863 – December, 1865) was a short-lived but significant journal published in New York by the Society for the Advancement of Truth in Art. The society and its journal espoused the aesthetic principles of John Ruskin and the English Pre-Raphaelite movement.

- John Ruskin Quotations.

- Ruskin Materials at Victorian Web.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.

↧ Download as ZWI file | Last modified: 02/04/2023 02:16:42 | 31 views

☰ Source: https://www.newworldencyclopedia.org/entry/John_Ruskin | License: CC BY-SA 3.0

ZWI signed:

ZWI signed:

KSF

KSF