Golden Calf

From Nwe

From Nwe The golden calf (עגל הזהב), in Jewish tradition, was an idol made by Aaron for the Israelites during Moses' absence on Mount Sinai. It was also a statue featured at the national shrines of the later Kingdom of Israel at Dan and Bethel.

In Hebrew, the incident at Sinai is known as "Chet ha'Egel" (חטא העגל) or "The Sin of the Calf." It is first mentioned in Exodus 32:4. In Egypt, where the Hebrews had recently resided, the Apis Bull was the comparable object of worship, which the Hebrews may have sought to revive in the wilderness. Among the Egyptians' and Hebrews' neighbors in the Ancient Near East and in the Aegean, the wild bull aurochs was widely worshiped, often as the Lunar Bull and as the creature of El. The latter tradition may also have been long known to the Israelites, who also worshiped El, later calling him Yahweh, the Lord (Exodus 6:3).

Critical scholarship suggests that the golden calf story may have originated as a polemic against the northern Israelite shrines that featured statues of golden bull-calves, while the rival Temple of Jerusalem was adorned with golden images of cherubum. In this view the statement of the northern king Jeroboam in unveiling the calf statue at Bethel—"Here is Elohim, O Israel"—was originally meant to convey the idea that Yahweh/El could be worshiped as well at Bethel as Jerusalem. The bull calf statue at Bethel lasted throughout the history of the Kingdom of Israel, much to the dismay of the Judah-oriented biblical writers. The shrine was finally destroyed by King Josiah of Judah in the late seventh century B.C.E.

The story of the golden calf receives much attention in rabbinical tradition, which downplays Aaron's responsibility in the matter, as does the account in the Qur'an. Over the centuries, the golden calf has become an enduring symbol of decadence, materialism, and putting money before what really matters in life.

Biblical narrative

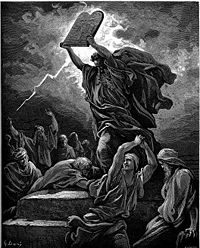

When Moses went up onto Mount Sinai to receive the Ten Commandments (Exodus 19:20), he left the Israelites for 40 days and 40 nights (Exodus 24:18). The Israelites feared that he would not return, and asked Aaron to show them a visible image of the divine (Exodus 32:1), despite previously having been commanded not to do such a thing (Exodus 20:4). The Bible does not note Aaron's opinion of this request, merely that he complied and gathered up the Israelites' golden earrings. He then melted them and constructed the golden calf—or in his own explanation to Moses: "I told them, 'Whoever has any gold jewelry, take it off.' Then they gave me the gold, and I threw it into the fire, and out came this calf!" (Exodus 32:24)

Aaron also built an altar for the calf, and proclaimed that the next day would be a "festival to the Lord." In the morning, the Israelites made offerings at the altar and celebrated a feast. When Moses descended from the mountain, he became enraged at their festivities and broke the tablets containing the Ten Commandments given by God on Sinai. He then took the calf, burned it in the fire, ground it to powder, scattered it on the water, and made the Israelites drink it. Moses then ordered his fellow Levites to slaughter thousands of those who had participated in the idolatry.

After this, The Lord told Moses that he intended to eliminate the Israelites altogether. Moses pleaded that they should be spared (Exodus 32:11), and God relented.

Having broken the tablets in his anger, Moses returned to Sinai again (Exodus 34:2) to receive replacements. Fasting and praying another 40 days, he accomplished this task, and this time the Israelites united with him and Aaron to successfully establish the Tabernacle and begin their journey through the wilderness to Canaan.

Interpretation

Within the context of the narrative, God has just finished delivering the Ten Commandments to the Israelites, which included the Second Commandment regarding the prohibition against idolatry, that is, the making of images to be used in worship. Some scholars have suggested that the Israelites were worshiping the Egyptian god Apis, falling back into what they had known for centuries while in captivity.

This interpretation is problematic, however, in light of the Bible's statement that Aaron "built an altar in front of the calf and announced, 'Tomorrow there will be a festival to the Lord.'" Moreover, his statement "this is elohim, O Israel, who brought you out of Egypt"—often translated as "these are your gods"—is probably better rendered as "this is God," given the fact that "God" is the normal translation for "Elohim" throughout the Hebrew Bible. The larger context clearly shows that the Israelites were aware of Yahweh as the agent of the Exodus.

It should also be considered that Aaron had earlier been commanded to sacrifice young bulls (Exodus 24:5) to Yahweh and that Israelite altars throughout their history were constructed with "horns" at the corners. It is possible, therefore, that the golden calf was created as a material representation of the sacrifices that Israelites had long presented to Yahweh/Elohim. Moreover, El—the name of God in Abraham's day—is represented in Canaanite religion as "Bull El," and could very well have been thought of as such by the Israelites. The sin of the Israelites thus seems to be one of an idolatrous worship of Yahweh/El, not the worship of a different deity.

The golden calves of Bethel and Dan

In later Israelite history, 1 Kings 12:28, after King Jeroboam I had established the northern Kingdom of Israel, he created northern shrines at Dan and Bethel as alternative pilgrimage destinations to Jerusalem. At each of these high places, he constructed, among other religious structures, a golden calf, declaring: "It is too much for you to go up to Jerusalem. Here is elohim, O Israel, who brought you up out of Egypt."

The construction of these two golden calves was characterized as gross blasphemy and idolatry by the authors of the Book of Kings, on a par with the original golden calf episode. Moreover, according to the Book of Deuteronomy Jerusalem was the only authorized place where sacrifices to Yahweh could be offered (Deuteronomy 12:13-14), and thus every future king of Israel would be denounced in Kings as repeating the "sin of Jeroboam" and leading the whole nation of Israel likewise to sin. Even Jehu, the most zealously pro-Yahweh and anti-Baal king of Israel, was not exempt from this criticism:

So Jehu destroyed Baal worship in Israel. However, he did not turn away from the sins of Jeroboam, son of Nebat, which he had caused Israel to commit—the worship of the golden calves at Bethel and Dan. (2 Kings 10:28-29)

The shrine at Bethel continued to exist even after the northern kingdom itself was destroyed by Assyria in 822 B.C.E. It was later obliterated by King Josiah of Judah during the religious reforms he instituted in the late seventh century:

Even the altar at Bethel, the high place made by Jeroboam, son of Nebat, who had caused Israel to sin—even that altar and high place he demolished. He burned the high place and ground it to powder, and burned the Asherah pole also.

Critical views

This scenario begs the question as to whether the "Jerusalem only" tradition actually originated with God, or with the priests who wrote the biblical narratives. To critical scholars, it must also be asked whether the "original" golden calf story was even a historical event, or a legend designed to denigrate the northern shrines that competed with the Temple of Jerusalem. The Jerusalem temple, after all, itself boasted of impressive golden cherubim that somehow were exempt from criticism as "graven images."

The story also raises a number of other questions: How can gold be burnt? How can burnt gold be ground to powder? Why was Aaron, who went on to be the high priest, not punished for his action?

The documentary hypothesis answers the last question by pointing out that the story of the golden calf is not present in the Priestly source, which portrays Aaron as a righteous man of God who established the priestly tradition inherited at Jerusalem. The story comes instead in the Elohist source, which may have originated at the northern shrine at Shiloh (Cross, 1973).[1] Moreover, in the Book of Deuteronomy, Aaron does seem to be punished for his sin, for he dies much earlier in the narrative—shortly after the golden calf incident (Deut. 10:6)—than he does in the Book of Numbers, where he dies after a long and successful career as the high priest of Israel (Numbers 20:28).

The grinding to powder action is also repeated in King Josiah's reign when "He burned the high place and ground it (the calf at Bethel) to powder," which echoes Moses' action in Exodus. Critical scholars suggest that the so-called "Books of Moses" were substantially edited, redacted, and partially written during Josiah's reign to present him as a "new Moses." (Finkelstein 2002)

Rabbinical views

"There is not a misfortune that Israel has suffered which is not partly a retribution for the sin of the calf," says a talmudic tradition (Sanh. 102a). The seriousness of the offense led some ancient rabbis, however, to express ameliorating circumstances and to apologize for Aaron's part in the affair. According to one opinion, the popular outcry to commit idolatry came from the Egyptians who had joined the Israelites in the Exodus. Indeed, the two Egyptian magicians, Yanos and Yambros—who had imitated Moses in reproducing the famous miracle of turning sticks into snakes—were instrumental in convincing Aaron that Moses would never return from the mountain. Satan, meanwhile had worked to sow powerful seeds of doubt among the Israelites (Shab. 89a; Tan., Ki Tissa, 19).

The heroic Hur, who had joined Aaron in physically supporting Moses at the battle against the Amalekites, was slain for urging continued belief in Moses' return, and Aaron was threatened with the same fate. Under these circumstances he ordered the male Israelites to bring the golden jewelry of their wives, believing that the women would be faithful, and would not cooperate. This indeed was the case, but the men then offered their own gold, and Aaron had no choice but to place it into the fire. Just as he later explained to Moses, a golden calf emerged from the flames alive and skipping!

Another reason given for the golden calf's creation is that when God appeared at Sinai, He descended in the heavenly chariot described by the prophet Ezekiel, with its four angelic beasts, one of them being the ox (Ezek. 1:10). It was this heavenly being which inspired the image that the Israelites worshiped, and Moses used this fact in his pleading with God to spare the Israelites. (Ex. R. xliii. 8).

The tribe of Levi did not join in the worship of the calf (Yoma 66b).[2]

Islamic view

The Islamic version of the story, like the Priestly source of the documentary hypothesis, omits any suggestion of wrongdoing by Aaron, who it regards as a prophet and therefore incapable of sin.

In the Qur'an, Moses had been gone for 40 days and his people were becoming restless, as God extended the time of his absence an additional ten days. Samiri, a man who was inclined toward evil, suggested: "In order to find true guidance, you need a god, and I shall provide one for you." So he, not Aaron, collected their gold jewelry, dug a hole for it, and lit a huge fire to melt it down. From the molten metal he fashioned the golden calf. The wind passing through the hollow idol created an eerie sound, causing many of the superstitious to believe it was a living god.

Aaron, however, was grieved by all this and spoke up: "O my people! You have been deceived. Your Lord is the Most Beneficent. Follow and obey me." They replied: "We shall stop worshiping this god only if Moses returns." The returning Moses saw his people singing and dancing around the calf statue. Furious at their pagan ritual, he flung down the tablet of the Law and tugged Aaron's beard, crying: "What held you back when you saw them going astray? Why did you not fight this corruption?" Aaron replied: "Let go of my beard! The fold considered me weak and were about to kill me. So make not the enemies rejoice over me, nor put me among the people who are wrong-doers."

Moses' anger subsided when he understood Aaron's helplessness, and he began to handle the situation calmly and wisely. He then turned to Samiri, who made an excuse similar to Aaron's in the biblical account. For his crime Samiri is sent into exile, away from human companionship.

Sacred calves, bulls, and cows

Bovine animals and their images have a long history of worship and sacrifice dating back to pre-historic times. Cave paintings of aurochs and other grazing animals date back tens of thousands of years throughout Europe, as well as in the Americas and Asia. Sacrifices of such animals likely involved expressions of gratitude to the spirit of the beasts for sustaining the life of the tribe and its members.

As animals came to be domesticated and as organized human settlements reached to the level of towns and cities, a more sophisticated religious system evolved. At the neolithic town of Çatalhöyük in modern Turkey, heads of bulls and other animals were often mounted on walls. Rooms with concentrations of these items may have been shrines or public meeting areas.

The bull was often lunar in Mesopotamia, its horns representing the crescent moon. Elaborate standards of the sacred bull of the Hattians were found at Alaca Höyük, and in Hittite mythologies such as Seri and Hurri (Day and Night), bulls carried the weather god Teshub on their backs. In Cyprus, bull masks made from real animal skulls were worn in rites.

In Egypt, the bull was worshiped as Apis, the embodiment of Ptah and later of Osiris. In Canaan, bulls and bull-calves were associated with both El and Baal, as well as with Baal's consort Anat. Ugaritic text CTA 10 describes Anat giving birth to a young bull, which she presents to Baal on Mount Saphon.

Hebrew tradition retained the tradition of sacrificing bulls and bull-calves, as well as the custom of building altars with horned corners. Unlike the northern Kingdom of Israel, the southern Kingdom of Judah rejected the use of bull images to symbolize the Hebrew god Yahweh, preferring instead to associate his worship with the sphinx-like cherubim. Jewish monotheistic tradition, inherited from Judah, firmly rejected any form of animal veneration or images of God.

For the Greeks, the bull was strongly linked to the Bull of Crete: Theseus of Athens had to capture the ancient sacred bull of Marathon before he faced the bull-man, the Minotaur. Earlier Minoan frescoes and ceramics depict bull-leaping rituals in which participants of both sexes vaulted over bulls by grasping their horns. Vestiges of such customs persist today in such traditions as bull-fights and the running of the bulls.

In Olympian Greek mythology, Hera's epithet was "ox-eyed." Her priestess Io took the form of a heifer when Zeus coupled with her. Zeus himself, in the form of a bull that came forth from the sea, abducted the high-born Phoenician Europa and brought her, significantly, to Crete.

Dionysus was another god who was strongly linked to the bull. In a hymn from Olympia at a festival for Hera, Dionysus is invited to come forth "with bull-foot raging." Quite frequently he is portrayed with bull horns, and in an older myth, Dionysus is slaughtered as a bull calf and eaten by the Titans. In the later cult of Mithras, bull mythology also figured significantly and bathing in a bull's blood was the initiatory rite.

In India, the ancient Vedic sacrifices, after which the sanctified meat was eaten, included bovines, and the Ashvalayana Grhya Sutras prescribe the sacrifice of a cow for consumption. In today's Hinduism, in which vegetarianism predominates, the cow is still considered sacred but is no longer sacrificed or eaten. Its protection is a recurrent theme in which she is symbolic of abundance, of the sanctity of all life and of the earth that gives much while asking nothing in return.

Notes

- ↑ One version of this theory suggests that the Shiloh priesthood stood in opposition both to Jerusalem, to whom it had lost the Ark of the Covenant and central authority it once possessed, and Bethel, which was chosen by Jeroboam as the national shrine of Israel even though the prophet of Shiloh, Abijah, had originally commissioned Jeroboam to establish an independent northern kingdom.

- ↑ This section is based on the public-domain article "Calf, Golden" www.jewishencyclopedia.com in the Jewish Encyclopedia, Retrieved November 26, 20187.

References

ISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Cross, Frank Moore. Canaanite Myth and Hebrew Epic, Harvard University Press, 1997. ISBN 0674091760

- Farbridge, Maurice H. Studies in Biblical and Semitic Symbolism. The Library of Biblical studies. New York: Ktav Pub. House, 1970. ISBN 978-0870680465

- Finkelstein, Israel, The Bible Unearthed: Archaeology's New Vision of Ancient Israel and the Origin of Its Sacred Texts. Free Press, 2002. ISBN 0684869136

- Sarna, Nahum, Exploring Exodus: The Origins of Biblical Israel. Shocken Books, 1996. ISBN 978-0805210637.

External links

All links retrieved November 26, 2018.

- The Golden calf from a Jewish perspective. www.chabad.org.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.

↧ Download as ZWI file | Last modified: 02/03/2023 22:00:56 | 121 views

☰ Source: https://www.newworldencyclopedia.org/entry/Golden_Calf | License: CC BY-SA 3.0

ZWI signed:

ZWI signed:

KSF

KSF