Saladin

From Conservapedia

From Conservapedia Saladin or Salah al-Din (Arabic: صلاح الدين الأيوبي) was a Kurdish Muslim Sultan (Tikrit, 1138-1193). He is best known for successful battles against the European Christian Crusaders in the Third Crusade, and for recapturing Jerusalem. About half of his career as a ruler was spent subduing and conquering other Muslim rulers and building Egypt into a regional power. Rulers in North Africa as well as the Abbasid caliph were more than a little concerned about Saladin's rise.

Saladin was generally a successful general, but he was defeated by Richard I (who was the King of England at the time) at the battle of Arsuf in 1191. He also suffered a major defeat at the Battle of Montgisard in 1177 against King Baldwin IV of the Latin Kingdom of Jerusalem.Career[edit]

Saladin came from a family in northern Syria which produced numerous prominent government and military leaders under the rule of the Zangid dynasty. In 1152 he joined the staff of his uncle Shirkuh and later accompanied (1169) Shirkuh, who headed a Zangid army, to Egypt, where he helped the Fatamid rulers resist the Crusaders. In 1171 Saladin became the Fatimid vizier (prime minister), with the mission of repulsing the Crusaders. He helped revive the idea of jihad as a holy war. In previous centuries, it had become little more than a minor routine obligation that rulers simply did not perform out of conviction. They only had to make an appearance. Jihad as a source of legitimization and a form of war resurfaced under the leadership of Zengi, one of the least religious participants of the Crusading era.

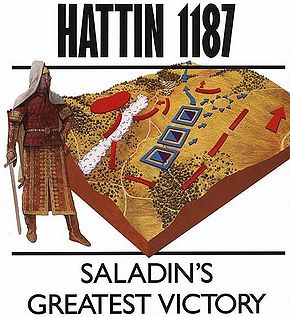

At the death in 1174 of the Zangid ruler in Syria, Saladin set out to conquer the Zangid kingdom as a preliminary to his holy war (jihad) against the Crusaders. Launching the jihad in 1187, Saladin was victorious at Hattin, recaptured Jerusalem, and drove the Crusaders back to the coast. These events prompted the Christians to mount the Third Crusade (1189–92), pitting Saladin against Kings Richard I of England. The Crusaders succeeded only in capturing Acre, and the Peace of Ramleh (1192) left the Latin Kingdom of Jerusalem with only a small strip of land along the Mediterranean coast.

Egypt[edit]

He solidified his power base in 1171 when he overthrew the Fatimid dynasty, returning Egypt to Islamic orthodoxy and becoming sole ruler there. Saladin made Egypt the major power in the Middle East. He established a stable dynasty, encouraged education, and reformed the financial structure to support the armed Kurdish and Turkish cavalry. Saladin's policies began a long period of economic prosperity, population growth, and cultural revival.

Saladin vs Richard[edit]

Saladin's encounters with King Richard I of England are recounted as a great romantic military rivalry. Regularly regarded as a fine example of chivalry, both Richard and Saladin treated each other with enormous respect during the conflict, and Saladin sent Richard fruit and other goods when he was suffering from severe dysentery during the campaign. Similarly, Richard sent Saladin fine English woolens when he heard that Saladin was suffering from flu. Nevertheless, Richard executed thousands of Muslim prisoners outside the walls of Acre during the siege, an act Saladin did not reciprocate.

Image and memory[edit]

Saladin is one of the few Muslims who stood out in European memory. He has been credited as the paragon of chivalry, romanticized as the most humane of all participants in the wars, and also demonized as a crafty political manipulator.

In Dante's Divine Comedy, Saladin appears in Limbo along with other virtuous non-Christians. He is the only Muslim to be honored in this way.

The Enlightenment reshaped the image of Saladin. Voltaire portrayed him as an example of a Muslim with greater natural virtue than any crusader in order to ridicule Christianity. During the Romantic era, Saladin was also in high esteem, especially through Sir Walter Scott's novels. Although many of Saladin's historically attested actions were quite magnanimous, Scott often enhanced his image with fictitious events.

Until the nineteenth century, Muslims showed little interest in the Crusades or in Saladin. With the outset of European imperialism, especially the British takeover of Egypt in the 1880s, Saladin was rediscovered as a cultural hero for Muslims. After World War I Saladin's image in the Muslim world took a new twist: he became the national hero of the Kurds, while Arabs latched onto him as a Pan-Islamic hero, and Turkey transformed him into a Turk. Meanwhile, Shia' Muslims typically view him as a villain.[1]

Further reading[edit]

- Möhring, Hannes. Saladin: The Sultan and His Times, 1138--1193 (2008). 144 pages; scholarly

- Newby, P. H. Saladin in His Time (1984)

- Nicolle, David. Saladin and the Saracens (1986) 48pp excerpt and text search, popular

- Nicolle, David. Hattin 1187: Saladin's greatest victory (1993) 96pp; excerpt and text search, popular

- Regan, G. Saladin and the Fall of Jerusalem (1988)

References[edit]

- ↑ See Möhring,(2008)

Categories: [Military Commanders] [Muslims] [Crusades] [Medieval History] [Middle East] [Egyptian History]

↧ Download as ZWI file | Last modified: 02/25/2023 18:32:06 | 50 views

☰ Source: https://www.conservapedia.com/Saladin | License: CC BY-SA 3.0

ZWI signed:

ZWI signed:

KSF

KSF