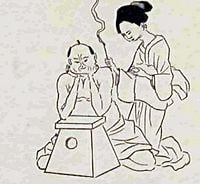

Moxa Treatment

From Nwe

From Nwe Moxibustion (Chinese: 灸; pinyin: jiǔ) or moxa treatment is an oriental medicine therapy involving the burning of moxa or mugwort herb (Artemisia vulgaris) close to the skin to treat diseases or produce analgesia (pain relief). Moxibustion may also utilize wormwood or other combustible and slow-burning substances. The purpose is to strengthen and stimulate the blood and qi (life energy) of the body.

Moxibustion plays an important role in the traditional medical systems of China, Japan, Korea, Vietnam, Tibet, and Mongolia. The basic technique involves placing burning mugwort over the affected area on the body, particularly on an acupuncture point, and removing it before burning the skin (Kim 2001). Suppliers usually age the mugwort and grind it up to a fluff; practitioners burn the fluff or process it further into a stick that may resemble a (non-smokable) cigar or into a cone. They can use it indirectly, with acupuncture needles, or sometimes burn it on a patient's skin.

Moxibustion is generally used in conjunction with acupuncture techniques, and the Chinese character for acupuncture translates literally into "acupuncture-moxibustion" (Kim 2001). Moxibustion has been used for perhaps more than 3,000 years (Kim 2001).

Moxibustion has been shown, in experimental trials, to have success in turning breech babies (Cardini and Huang 2001; Neri et al. 2002, 2004), and it also is used in such conditions as treating inflammations, menstrual cramps, chronic problems, and "deficient conditions" (weakness).

Mugwort

| Mugwort | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

||||||||||||||

| Scientific classification | ||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||

| Artemisia vulgaris L. |

Mugwort is a tall, herbaceous plant, Artemisia vulgaris, that is native to temperate Europe, Asia, and northern Africa, as well present in North America. It is also known as common artemisia, wild wormwood, felon herb, chrysanthemum weed, and St. John's plant (not to be confused with St John's wort). It is called Mogusa or Yomogi in Japan. Mugwort is one of several species in the genus Artemisia with names containing mugwort. It is a very common plant growing on nitrogenous soils, like weedy and uncultivated areas, such as waste places and roadsides.

Mugwort grows about one to two meters in height (rarely 2.5 meters), with a woody root. The leaves are 5-20 centimeters long, dark green on top, pinnate, and light green with dense white tomentose hairs on the underside. They are alternately arranged long the erect, grooved stem, that is slightly hairy and may be tinged with a purple hue (Hanrahan 2001). The leaves have a pungent odor when crushed (Hanrahan 2001). The rather small flowers (five millimeters long) are radially symmetrical with many yellow or dark red petals. The narrow and numerous capitula (flower heads) spread out in racemose panicles. It flowers from July to September, clustering in long spikes at the top of the plant in late summer (Hanrahan 2001).

Mugwort is a different species from wormwood (Artemisia absinthium, or absinth wormwood, although several species in the Artemisia genus have the common name of wormwood). Mugwort is distinguished from wormwood by the leaves being pale green or white on the underside and by the leaf segments being pointed, not blunt.

Chinese mugwort (A. verlotiorum) is often confused with mugwort (A. vulgaris). It has oblong reddish to brown capitula, its stems are green, and the leaves broader, lighter colored, and more dense on the stem. The plant has a stronger and more pleasant smell than that of mugwort. It flowers very late in the summer, but reproduces mainly by stolons, thus forming thick groups. Chinese mugwort shares the same habitat as common mugwort and both are very common.

Uses other than moxibustion

The leaves and buds, best picked shortly before the plant flowers in July to September, were used as a bitter flavoring agent to season fat meat and fish. In Germany, known as Beifuß, it is mainly used to season goose, especially the roast goose traditionally eaten for Christmas. Mugwort is also used in Korea and Japan to give festive rice cakes a greenish color. It is a common seasoning in Korean soups and pancakes. Known as a blood cleanser, it is believed to have different medicinal properties depending on the region it is collected. In the Middle Ages Mugwort was used as part of a herbal mixture called gruit, used in the flavoring of beer before the widespread introduction of hops.

However, mugwort contains thujone, which is toxic. Pregnant women, in particular, should avoid consuming large amounts of mugwort.

In addition to consumption and being used in the pulverized and aged form in moxibustion, mugwort is also used medicinally in other ways. The plant contains ethereal oils (such as cineole, or wormwood oil, and thujone), flavonoids, triterpenes, and coumarin derivatives. Chewing some leaves is believed to relieve fatigue and stimulate the nervous system. It was also used as an anthelminthic, so it is sometimes confused with wormwood (Artemisia absinthium).

Mugwort is considered a herbal ally for women, with benefit for regulating the menstrual cycle and easing the transition to menopause (Hanrahan 2001). It acts as an emmenagogue—an agent that increases blood circulation to the pelvic area and the uterus—and is considered a useful remedy for painful or irregular menstruation and to promote labor (Hanrahan 2001).

In the Middle Ages, mugwort was used as a magical protective herb. Mugwort was used to repel insects, especially moths, from gardens. Mugwort has also been used from ancient times as a remedy against fatigue and to protect travelers against evil spirits and wild animals. Roman soldiers put mugwort in their sandals to protect their feet against fatigue. Mugwort was planted along roadside by the Romans so that a passerby could put it in his or her shoes to relieve aching feet (Hanrahan 2001).

Much used in witchcraft, mugwort is said to be useful in inducing lucid dreaming and astral travel. Consumption of the plant, or a tincture thereof, prior to sleeping is said to increase the intensity of dreams, the level of control, and to aid in the recall of dreams upon waking. One common method of ingestion is to smoke the plant.

In North and South America, indigenous peoples regard mugwort as a sacred plant of divination and spiritual healing, as well as a panacea. Mugwort among other herbs were often bound into smudge sticks.

Terminology

The root word "moxa" actually comes from the Japanese mogusa (艾) (the u is not very strongly enunciated). Yomogi (蓬) also serves as a synonym for moxa in Japan. Chinese uses the same character as mogusa, but pronounced differently: ài, also called àiróng (艾絨) (meaning "velvet of ài").

The Chinese character for moxa forms one half of the two making up the Chinese word that often gets translated as "acupuncture" zhēnjiǔ (鍼灸).

The term mugwort may come from the old English word moughte, meaning "moth," or mucgwyrt, meaning "midgewort," referring to the use of the plant to repel moths and other insects (Hanrahan 2001). The generic term, Artemisia, comes from the Greek moon goddess Artemis, a patron of women, reflecting mugworts being considered a herbal ally for women (Hanrahan 2001).

History, description, and benefits

The practice of moxibustion appears to trace to more than 3,000 years ago, as during the Shang Dynasty in China, hieroglyphs of acupuncture and moxibustion were found on bones and tortoise shells (Kim 2001). Medical historians believe that moxibustion pre-dated acupuncture, and needling came to supplement moxa after the second century B.C.E.

Moxibustion involves burning mugwort over the body, such as over the elbow to treat a patient with tendonitis (Kim 2001). It is almost always used in conjunction with acupuncture, and is particularly positioned over acupuncture points (Kim 2001). For example, the burning mugwort may be positioned over the meridian called the Ren Channel, the center line of the lower abdomen, in cases of menstrual cramps, and over acu-point BL67, located on the outside of the big toes, in the case of breech presentation babies (Kim 2001). The mugwort can come in a cone, or in sticks that resemble the length and circumference of a cigar (Kim 2001).

Different schools of acupuncture use moxa in varying degrees. For example a five-element acupuncturist will use moxa directly on the skin, while a Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM)-style practitioner will use rolls of moxa and hold them over the point treated. It can also be burnt atop a fine slice of ginger root to prevent scarring.

Practitioners use moxa to warm regions and acupuncture points with the intention of stimulating circulation through the points and inducing a smoother flow of blood and qi (life energy).

Moxibustion is used for many conditions. It is claimed that moxibustion militates against cold and dampness in the body, to treat inflammations, and for menstrual cramps. Kim (2001) stated that often the menstrual cramps disappear immediately.

Moxibustion also has been attributed to have success in turning breech babies (Kanakura et al. 2001). Kim (2001) and Hanrahan (2001) report that a 1998 study published in the Journal of the American Medical Association report that 75 percent of 130 pregnant women in the study had breech fetuses that turned in the normal position after the mother was treated with moxibustion. This study (Cardini and Huang 1998) studied Chinese women at 33 weeks of pregnancy, demonstrating cephalic change within two weeks in 75 percent of fetuses carried by patients who were treated with moxibustion, as opposed to 48 percent in the control group. A more recent study, involving 226 Italian patients, showed cephalic presentation at delivery in 54 percent of women treated between 33 and 35 weeks with acupuncture and moxibustion, vs. 37 percent in the control group (Neri et al. 2004).

Moxibustion significantly increases fetal movement, and the technique is said to stimulate circulation and energy flow after the acupuncture point BL67 near the toenail of the fifth toe is stimulated (Kim 2001). It has also been shown that acupuncture plus moxibustion slows fetal heart rates while increasing fetal movement (Neri et al. 2002).

Practitioners consider moxibustion to be especially effective in the treatment of chronic problems, "deficient conditions" (weakness), and gerontology. Bian Que (fl. circa 500 B.C.E.), one of the most famous semi-legendary doctors of Chinese antiquity and the first specialist in moxibustion, discussed the benefits of moxa over acupuncture in his classic work. He asserted that moxa could add new energy to the body and could treat both excess and deficient conditions. On the other hand, he advised against the use of acupuncture in an already deficient (weak) patient, on the grounds that needle manipulation would leak too much energy.

A huge classical work, Gao Huang Shu (膏肓俞), specializes solely in treatment indications for moxa on a single point (穴).

Note that Taoists use scarring moxibustion along with Chinese medical astrology for longevity.

References

ISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Cardini, F., and W. X. Huang. 1998. Moxibustion for correction of breech presentation: A randomized controlled trial. JAMA 280(18): 1580-1584.

- Hanrahan, C. 2001. Mugwort Encyclopedia of Alternative Medicine in FindArticles.com. Retrieved January 16, 2008.

- Kanakura, Y., K. Kometani, T. Nagata, K. Niwa, H. Kamatsuki, Y. Shinzato, and Y. Tokunaga. 2001. Moxibustion treatment of breech presentation American Journal of Chinese Medicine. Retrieved January 16, 2008.

- Kim, K. Y. 2001. Moxibustion. In K. M. Krapp and J. L. Longe, The Gale Encyclopedia of Alternative Medicine. Farmington Hills, Mich: Thomson/Gale. ISBN 0787649996.

- Neri, I., M. Fazzio, S. Menghini, A. Volpe, and F. Facchinetti. 2002. Non-stress test changes during acupuncture plus moxibustion on BL67 point in breech presentation. Journal of the Society for Gynecological Investigation 9(3): 158-162.

- Neri, I., G. Airola, G. Contu, G. Allais, F. Facchinetti, and C. Benedetto. 2004. Acupuncture plus moxibustion to resolve breech presentation: A randomized controlled study. Journal of Maternal-Fetal and Neonatal Medicine 15(4): 247-252.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.

↧ Download as ZWI file | Last modified: 02/04/2023 07:15:13 | 47 views

☰ Source: https://www.newworldencyclopedia.org/entry/Moxibustion | License: CC BY-SA 3.0

ZWI signed:

ZWI signed:

KSF

KSF