Pompey

From Nwe

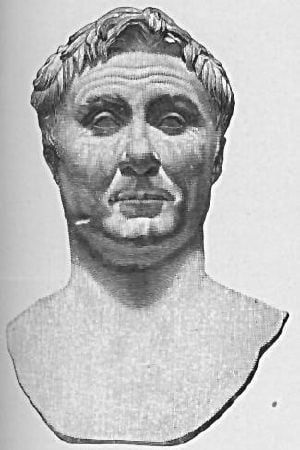

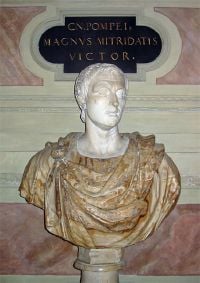

From Nwe Gnaeus Pompeius Magnus, commonly known as Pompey /'pɑmpi/, Pompey the Great or Pompey the Triumvir (September 29, 106 B.C.E.–September 28, 48 B.C.E.), was a distinguished military and political leader of the late Roman Republic. Hailing from an Italian provincial background, after military triumphs he established a place for himself in the ranks of Roman nobility, and was granted the cognomen the Great for his accomplishments. Pompey was a rival of Marcus Licinius Crassus, and at first an ally to Gaius Julius Caesar. The three politicians dominated the Late Roman republic through a political alliance called the First Triumvirate. After the death of Crassus (as well as Pompey's wife and Julius Caesar's only Roman child Julia), Pompey and Caesar became rivals, disputing the leadership of the Roman state in what is now called Caesar's civil war, an episode in the larger Roman Revolution which saw the death of the Republic and the rise of the Emperors of Rome.

Pompey fought on the side of the Optimates, the conservative faction in the Roman Senate, until he was defeated by Caesar. He then sought refuge in Egypt, where he was assassinated. During his career, Pompey annexed Palestine and much of Asia, leaving a permanent mark on the geo-political map of the world. It was due to Pompey's conquests that Christianity began within the Roman World and was able to spread quickly across its imperial territory. Links already existed between the Middle East and the North Mediterranean spaces but new channels now developed for commercial and cultural and religious exchange. Pompey was accompanied by scholars, who took the results of their researches back to Rome. In the long term, this contributed to the way people have befitted and learned from other cultures and civilizations, so that humanity becomes more inter-dependent and inter-connected. Pompey, more than most of his peers, tended to see others as equally human; he valued and admired different cultures.

Early life and political debut

His father, Pompeius Strabo (sometimes with the cognomen 'Carnifex' (The Butcher) attached), was an extremely wealthy man from the Italian region of Picenum, but his family was one of the ancient families who had dominated Roman politics. Nevertheless, his father had climbed through the traditional cursus honorum, being quaestor in 104 B.C.E., praetor in 92 B.C.E. and consul in 89 B.C.E. However, despite his civil stature, Pompey's father was greatly disliked by the public. During Sulla's siege of the Colline Gate, which was led by Strabo, the citizens of Rome blamed Magnus' father for the severe outbreaks of dysentery and other diseases. After his death, they hauled his naked body through the streets by meat hooks. Pompey had scarcely left school before he was summoned to serve under his father in the Social war, and in 89B.C.E., at the age of seventeen, he fought against the Italians. Fully involved in his father's military and political affairs, he would continue with his father until Strabo's death two years afterward. According to Plutarch, who was sympathetic to Pompey, he was very popular and considered a look-alike of Alexander the Great. James Ussher records that Pompey admired Alexander from his youth and "imitated both his actions and his advice."[1]

His father died in 87 B.C.E., in the conflicts between Gaius Marius and Lucius Cornelius Sulla, leaving young Pompey in control of his family affairs and fortune. For the next few years, the Marian party had possession of Italy and Pompey, who adhered to the aristocratic party, was obliged to keep in the background. Returning to Rome, he was prosecuted for misappropriation of plunder but quickly acquitted. His acquittal was certainly helped by the fact that he was betrothed to the judge's daughter, Antistia. Pompey sided with Sulla after his return from Greece in 83 B.C.E. Sulla was expecting trouble with Gnaeus Papirius Carbo's regime and found the 23-year-old Pompey and the three veteran legions very useful. When Pompey, displaying great military abilities in opposing the Marian generals who surrounded him, succeeded in joining Sulla via a cocktail of blackmail and arrogance, he was saluted by the latter with the title of Imperator. Sulla was also the first to refer to him as Magnus, however it is believed this was done in jest, and Pompeius only used the title later in his career. This political alliance boosted Pompey's career greatly and Sulla, now the Dictator in absolute control of the Roman world, persuaded Pompey to divorce his wife and marry his stepdaughter Aemilia Scaura, who was pregnant by her current husband, in order to bind his young ally more closely to him.

Sicily and Africa

Although his young age kept him a privatus (a man holding no political office of—or associated with—the cursus honorum), Pompey was a very rich man and a talented general in control of three veteran legions. Moreover, he was ambitious for glory and power. During the remainder of the war in Italy, Pompey distinguished himself as one of the most successful of Sulla's generals; and when the war in Italy was brought to a close, Sulla sent Pompey against the Marian party in Sicily and Africa. Happy to acknowledge his wife's son-in-law's wishes, and to clear his own situation as dictator, Sulla first sent Pompey to recover Sicily from the Marians.

Pompey made himself master of the island in 82 B.C.E. Sicily was strategically very important, since the island held the majority of Rome's grain supply. Without it, the city population would starve and riots would certainly ensue. Pompey dealt with the resistance with a harsh hand, executing Gnaeus Papirius Carbo and his supporters.[2] When the citizens complained about his methods, he replied with one of his most famous quotations: "Won't you stop citing laws to us who have our swords by our sides?" Pompey routed the opposing forces in Sicily and then in 81 B.C.E. he crossed over to the Roman province of Africa, where he defeated Gnaeus Domitius Ahenobarbus and the Numidian king Hiarbas, after a hard-fought battle.

After this continued string of unbroken victories, Pompey was proclaimed Imperator by his troops on the field in Africa. On his return to Rome in the same year, he was received with enthusiasm by the people and was greeted by Sulla with the cognomen Magnus, (meaning "the Great"), with most commentators suspecting that Sulla gave it as a cruel and ironic joke; it was some time before Pompey made widespread use of it.

Pompey was not satisfied with this distinction, and demanded a triumph for his African victories, which Sulla at first refused; Pompey himself refused to disband his legions and appeared with his demand at the gates of Rome where, amazingly, Sulla gave in, overcome by Pompey's importunity, and allowing him to have his own way. However, in an act calculated to cut Pompey down to size, Sulla had his own triumph first, then allowed Metellus Pius to triumph, relegating Pompey to a third triumph in quick succession, on the assumption that Rome would become bored by the third one. Accordingly, Pompey attempted to enter Rome in triumph towed by an elephant. As it happened, it would not fit through the gate and some hasty re-planning was needed, much to the embarrassment of Pompey and amusement of those present.

Quintus Sertorius and Spartacus

Pompey's reputation for military genius and occasional bad judgment continued when, after suppressing the revolt by Lepidus (whom he had initially supported for consul, against Sulla's wishes), he demanded proconsular imperium (although he had not yet served as Consul) to go to Hispania (the Iberian Peninsula, comprising modern Spain and Portugal) to fight against Quintus Sertorius, a Marian general. The aristocracy, however, now beginning to fear the young and successful general, was reluctant to provide him with the needed authority. Pompey countered by refusing to disband his legions until his request was granted. However, in Hispania, Sertorius had for the last three years successfully opposed Quintus Caecilius Metellus Pius, one of the ablest of Sulla's generals, and ultimately it became necessary to send the latter some effectual assistance. As a result, the Senate, with considerable lack of enthusiasm, determined to send Pompey to Hispania against Sertorius, with the title of proconsul, and with equal powers to Metellus.

Pompey remained in Hispania between five and six years 76–71 B.C.E.; but neither he nor Metellus was able to achieve a clean victory or gain any decisive advantage on the battlefield over Sertorius. But when Sertorius was treacherously murdered by his own officer Marcus Perperna Vento in 72, the war was speedily brought to a close. Perperna was easily defeated by Pompey in their first battle, and the whole of Hispania was subdued by the early part of the following year 71.

In the months after Sertorius' death, however, Pompey revealed one of his most significant talents: a genius for the organization and administration of a conquered province. Fair and generous terms extended his patronage throughout Hispania and into southern Gaul. While Crassus was facing Spartacus late in the Third Servile War in 71 B.C.E., Pompey returned to Italy with his army. In his march toward Rome he came upon the remains of the army of Spartacus and captured five thousand Spartacani who had survived Crassus and were attempting to flee. Pompey cut these fugitives to pieces, and therefore claimed for himself, in addition to all his other exploits, the glory of finishing the revolt. His attempt to take credit for ending the Servile war was an act that infuriated Crassus.

Disgruntled opponents, especially Crassus, said he was developing a talent for showing up late in a campaign and taking all the glory for its successful conclusion. This growing enmity between Crassus and Pompey would not be resolved for over a decade. Back in Rome, Pompey was now a candidate for the consulship; although he was ineligible by law, inasmuch as he was absent from Rome, had not yet reached the legal age, and had not held any of the lower offices of the state, still his election was certain. His military glory had charmed people, admirers seeing in Pompey the most brilliant general of the age; as it was known that the aristocracy looked upon Pompey with jealousy, many people ceased to regard him as belonging to this party and hoped to obtain, through him, a restoration of the rights and privileges of which they had been deprived by Sulla.

Pompey on December 31, 71 B.C.E., entered the city of Rome in his triumphal car, a simple eques, celebrating his second extralegal triumph for the victories in Hispania. In 71 B.C.E., at only 35 years of age (see cursus honorum), Pompey was elected Consul for the first time, serving in 70 B.C.E. as partner of Crassus, with the overwhelming support of the Roman population. This was an extraordinary measure: never before had a man been elevated from privatus to Consul in one swift move such as this. Pompeius, not even a member of the Senate, was never forgiven by most of Rome's noblemen, especially the boni for forcing that body to accept his nomination in the elections.

Rome's new frontier on the East

In his consulship (70 B.C.E.), Pompey openly broke with the aristocracy and became the great popular hero. By 69 B.C.E., Pompey was the darling of the Roman masses, although many Optimates were deeply suspicious of his intentions. He proposed and carried a law restoring to the tribunes the power of which they had been deprived by Sulla. He also afforded his powerful aid to the Lex Aurelia, proposed by the praetor Lucius Aurelius Cotta, by which the judices were to be taken in future from the senatus, equites, and tribuni aerarii, instead of from the senators exclusively, as Sulla had ordained. In carrying both these measures Pompey was strongly supported by Caesar, with whom he was thus brought into close connection. For the next two years (69 and 68 B.C.E.) Pompey remained in Rome. His primacy in the State was enhanced by two extraordinary proconsular commands, unprecedented in Roman history.

Campaign against the pirates

In 67 B.C.E., two years after his consulship, Pompey was nominated commander of a special naval task force to campaign against the pirates that menaced the Mediterranean. This command, like everything else in Pompey's life, was surrounded with polemic. The conservative faction of the Senate was most suspicious of his intentions and afraid of his power. The Optimates tried every means possible to avoid his appointment, tired of his constant appointment to what they saw as illegal and extraordinary commands. Significantly, Caesar was again one of a handful of senators who supported Pompey's command from the start. The nomination was then proposed by the Tribune of the Plebs Aulus Gabinius who proposed the Lex Gabinia, giving Pompey command in the war against the Mediterranean pirates, with extensive powers that gave him absolute control over the sea and the coasts for 50 miles inland, setting him above every military leader in the East. This bill was opposed by the aristocracy with the utmost vehemence, but was carried: Pompeius' ability as a general was too well known for any to stand against him in the elections, even his fellow ex-consul Marcus Licinius Crassus.

The pirates were at this time masters of the Mediterranean, and had not only plundered many cities on the coasts of Greece and Asia, but had even made descents upon Italy itself. As soon as Pompey received the command, he began to make his preparations for the war, and completed them by the end of the winter. His plans were crowned with complete success. Pompey divided the Mediterranean into thirteen separate areas, each under the command of one of his legates. In forty days he cleared the Western Sea of pirates, and restored communication between Hispania, Africa, and Italy. He then followed the main body of the pirates to their strongholds on the coast of Cilicia; after defeating their fleet, he induced a great part of them, by promises of pardon, to surrender to him. Many of these he settled at Soli, which was henceforward called Pompeiopolis.

Ultimately it took Pompey all of a summer to clear the Mediterranean of the danger of pirates. In three short months (67-66 B.C.E.), Pompey's forces had swept the Mediterranean clean of pirates, showing extraordinary precision, discipline, and organizational ability; so that, to adopt the panegyric of Cicero

- "Pompey made his preparations for the war at the end of the winter, entered upon it at the commencement of spring, and finished it in the middle of the summer."[3]

The quickness of the campaign showed that he was as talented a general at sea as on land, with strong logistic abilities. Pompey was hailed as the first man in Rome, "Primus inter pares" the first among equals.

Pompey in the East

Pompey was employed during the remainder of this year and the beginning of the following in visiting the cities of Cilicia and Pamphylia, and providing for the government of the newly-conquered districts. During his absence from Rome (66 B.C.E.), Pompey was nominated to succeed Lucius Licinius Lucullus in the command, take charge of the Third Mithridatic War and fight Mithridates VI of Pontus in the East. Lucullus, a well-born plebeian noble, made it known that he was incensed at the prospect of being replaced by a "new man" such as Pompey. Pompey responded by calling Lucullus a "Xerxes in a toga." Lucullus shot back by calling Pompey a "vulture" because he was always fed off the work of others, referring to his new command in the present war, as well as Pompey's actions at the climax of the war against Spartacus. The bill conferring upon him this command was proposed by the tribune Gaius Manilius, and was supported by Cicero in an oration which has come down to us (pro Lege Manilia). Like the Gabinian law, it was opposed by the whole weight of the aristocracy, but was carried triumphantly. The power of Mithridates had been broken by previous victories of Lucullus, and it was only left to Pompey to bring the war to a conclusion. This command essentially entrusted Pompey with the conquest and reorganization of the entire Eastern Mediterranean. Also, this was the second command that Caesar supported in favor of Pompey.

On the approach of Pompey, Mithridates retreated towards Armenia but was defeated. As Tigranes the Great now refused to receive him into his dominions, Mithridates resolved to plunge into the heart of Colchis, and thence make his way to his own dominions in the Cimmerian Bosporus. Pompey now turned his arms against Tigranes. However, conflict turned into peace once the two empires reached an agreement and became allies. In 65 B.C.E., Pompey set out in pursuit of Mithridates but he met with much opposition from the Caucasian Iberians and Albanians; and after advancing as far as Phasis in Colchis, where he met his legate Servilius, the admiral of his Euxine fleet, Pompey resolved to leave these districts. He accordingly retraced his steps, and spent the winter at Pontus, which he made into a Roman province. In 64 B.C.E. he marched into Syria, deposed the king Antiochus XIII Asiaticus, and made that country also a Roman province. In 63 B.C.E., he advanced further south, in order to establish the Roman supremacy in Phoenicia, Coele-Syria, and Judea (present day Israel). The Hellenized cities of the region, particularly the cities of the Decapolis, for centuries counted dates from Pompey's conquest, a calendar called the Pompeian era.

After that Pompey captured Jerusalem. At the time Judea was racked by civil war between two Jewish brothers who created religious factions: Hyrcanus II and Aristobulus II. The civil war was causing instability and it exposed Pompey's unprotected flank. He felt that he had to act. Both sides gave money to Pompey for assistance, and a picked delegation of Pharisees went in support of Hyrcanus II. Pompey decided to link forces with the good-natured Hyrcanus II, and their joint army of Romans and Jews besieged Jerusalem for three months, after which it was taken from Aristobulus II. Aristobulus II was crafty, though, and later succeeded in temporarily usurping the throne from Hyrcanus II. Subsequently, King Herod I executed Hyrcanus II in 31 B.C.E.

Pompey entered the Holy of Holies; this was only the second time that someone had dared to penetrate into this sacred spot. He went to the Temple to satisfy his curiosity about stories he had heard about the worship of the Jewish people. He made it a priority to find out whether the Jews had no physical statue or image of their god in their most sacred place of worship. To Pompey, it was inconceivable to worship a God without portraying him in a type of physical likeness, like a statue. What Pompey saw was unlike anything he had seen on his travels. He found no physical statue, religious image or pictorial description of the Hebrew God. Instead, he saw the Torah scrolls and was thoroughly confused.

Of the Jews there fell twelve thousand, but of the Romans very few.... and no small enormities were committed about the temple itself, which, in former ages, had been inaccessible, and seen by none; for Pompey went into it, and not a few of those that were with him also, and saw all that which it was unlawful for any other men to see but only for the high priests. There were in that temple the golden table, the holy candlestick, and the pouring vessels, and a great quantity of spices; and besides these there were among the treasures two thousand talents of sacred money: yet did Pompey touch nothing of all this, on account of his regard to religion; and in this point also he acted in a manner that was worthy of his virtue. The next day he gave order to those that had the charge of the temple to cleanse it, and to bring what offerings the law required to God; and restored the high priesthood to Hyrcanus, both because he had been useful to him in other respects, and because he hindered the Jews in the country from giving Aristobulus any assistance in his war against him. [4]

It was during the war in Judea that Pompey heard of the death of Mithridates.

With Tigranes as a friend and ally of Rome, the chain of Roman protectorates now extended as far east as the Black Sea and the Caucasus. The amount of tribute and bounty Pompey brought back to Rome was almost incalculable: Plutarch lists 20,000 talents in gold and silver added to the treasury, and the increase in taxes to the public treasury rose from 50 million to 85 million drachmas annually. His administrative brilliance was such that his dispositions endured largely unchanged until the fall of Rome.

Pompey conducted the campaigns of 65 to 62 B.C.E. and Rome annexed much of Asia firmly under its control. He imposed an overall settlement on the kings of the new eastern provinces, which took intelligent account of the geographical and political factors involved in creating Rome's new frontier on the East. After returning to Rome, Pompey said that he had waged war against twenty-two kings in the East.[5]

Pompey’s return to Rome

His third Triumph took place on the 29 September 61 B.C.E., on Pompey's 45th birthday, celebrating the victories over the pirates and in the East, and was to be an unforgettable event in Rome. Two entire days were scheduled for the enormous parade of spoils, prisoners, army and banners depicting battle scenes to complete the route between Campus Martius and the temple of Jupiter Optimus Maximus. To conclude the festivities, Pompey offered an immense triumphal banquet and made several donations to the people of Rome, enhancing his popularity even further.

Although now at his zenith, by this time Pompey had been largely absent from Rome for over 5 years and a new star had arisen. Pompey had been busy in Asia during the consternation of the Catiline Conspiracy, when Caesar pitted his will against that of the Consul Cicero and the rest of the Optimates. His old colleague and enemy, Crassus, had loaned Caesar money. Cicero was in eclipse, now hounded by the ill-will of Publius Clodius and his factional gangs. New alliances had been made and the conquering hero was out of touch.

Back in Rome, Pompey deftly dismissed his armies, disarming worries that he intended to spring from his conquests into domination of Rome as Dictator. Pompey sought new allies and pulled strings behind the political scenes. The Optimates had fought back to control much of the real workings of the Senate; in spite of his efforts, Pompey found their inner councils were closed to him. His settlements in the East were not promptly confirmed. The public lands he had promised his veterans were not forthcoming. From now on, Pompey's political maneuverings suggest that, although he toed a cautious line to avoid offending the conservatives, he was increasingly puzzled by Optimate reluctance to acknowledge his solid achievements. Pompey's frustration led him into strange political alliances.

Caesar and the First Triumvirate

Although Pompey and Crassus distrusted each other, by 61 B.C.E. their grievances pushed them both into an alliance with Caesar. Crassus' tax farming clients were being rebuffed at the same time that Pompey's veterans were being ignored. Thus entered Caesar, 6 years younger than Pompey, returning from service in Hispania, and ready to seek the consulship for 59 B.C.E. Caesar somehow managed to forge a political alliance with both Pompey and Crassus (the so-called First Triumvirate). Pompey and Crassus would make him Consul, and he would use his power as Consul to force their claims. Plutarch quotes Cato the Younger as later saying that the tragedy of Pompey was not that he was Caesar's defeated enemy, but that he had been, for too long, Caesar's friend and supporter.

Caesar's tempestuous consulship in 59 brought Pompey not only the land and political settlements he craved, but a new wife: Caesar's own young daughter, Julia. Pompey was supposedly besotted with his bride. After Caesar secured his proconsular command in Gaul at the end of his consular year, Pompey was given the governorship of Hispania Ulterior, yet was permitted to remain in Rome overseeing the critical Roman grain supply as curator annonae, exercising his command through subordinates. Pompey efficiently handled the grain issue, but his success at political intrigue was less sure.

The Optimates had never forgiven him for abandoning Cicero when Publius Clodius forced his exile. Only when Clodius began attacking Pompey was he persuaded to work with others towards Cicero's recall in 57 B.C.E. Once Cicero was back, his usual vocal magic helped soothe Pompey's position somewhat, but many still viewed Pompey as a traitor for his alliance with Caesar. Other agitators tried to persuade Pompey that Crassus was plotting to have him assassinated. Rumor (quoted by Plutarch) also suggested that the aging conqueror was losing interest in politics in favor of domestic life with his young wife. He was occupied by the details of construction of the mammoth complex later known as Pompey's Theater on the Campus Martius; not only the first permanent theater ever built in Rome, but an eye-popping complex of lavish porticoes, shops, and multi-service buildings.

Caesar, meanwhile, was gaining a greater name as a general of genius in his own right. By 56 B.C.E., the bonds between the three men were fraying. Caesar called first Crassus, then Pompey, to a secret meeting in the northern Italian town of Lucca to rethink both strategy and tactics. By this time, Caesar was no longer the amenable silent partner of the trio. At Lucca it was agreed that Pompey and Crassus would again stand for the consulship in 55 B.C.E. At their election, Caesar's command in Gaul would be extended for an additional five years, while Crassus would receive the governorship of Syria, (from which he longed to conquer Parthia and extend his own achievements). Pompey would continue to govern Hispania in absentia after their consular year. This time, however, opposition to the three men was electric, and it took bribery and corruption on an unprecedented scale to secure the election of Pompey and Crassus in 55 B.C.E. Their supporters received most of the important remaining offices. The violence between Clodius and other factions were building and civil unrest was becoming endemic.

Confrontation to war

The triumvirate was about to end, its bonds snapped by death: first, Pompey's wife (and at that time Caesar's only child), Julia, died in 54 B.C.E. in childbirth; later that year, Crassus and his army were annihilated by the Parthian armies at the Battle of Carrhae. Caesar's name, not Pompey's, was now firmly before the public as Rome's great new general. The public turmoil in Rome resulted in whispers as early as 54 that Pompey should be made dictator to force a return to law and order. After Julia's death, Caesar sought a second matrimonial alliance with Pompey, offering a marital alliance with his grandniece Octavia (future emperor Augustus's sister). This time, Pompey refused. In 52 B.C.E., he married Cornelia Metella, daughter of Quintus Caecilius Metellus Scipio, one of Caesar’s greatest enemies, and continued to drift toward the Optimates. It can be presumed that the Optimates had deemed Pompey the lesser of two evils.

In that year, the murder of Publius Clodius and the burning of the Curia Hostilia (the Senate House) by an inflamed mob led the Senate to beg Pompey to restore order, which he did with ruthless efficiency. The trial of the accused murderer, Titus Annius Milo, is notable in that Cicero, counsel for the defense, was so shaken by a Forum seething with armed soldiers that he was unable to complete his defense. After order was restored, the suspicious Senate and Cato, seeking desperately to avoid giving Pompey dictatorial powers, came up with the alternative of entitling him sole Consul without a colleague; thus his powers, although sweeping, were not unlimited. The title of Dictator brought with it memories of Sulla and his bloody proscriptions, a memory none could allow to happen once more. As a Dictator was unable to be punished by law for measures taken during office, Rome was uneasy in handing Pompey the title. By offering him to be Consul without a colleague, he was tied by the fact he could be brought to justice if anything he did was seen to be illegal.

While Caesar was fighting against Vercingetorix in Gaul, Pompey proceeded with a legislative agenda for Rome, which revealed that he was now covertly allied with Caesar's enemies. While instituting legal and military reorganization and reform, Pompey also passed a law making it possible to be retroactively prosecuted for electoral bribery—an action correctly interpreted by Caesar's allies as opening Caesar to prosecution once his imperium was ended. Pompey also prohibited Caesar from standing for the consulship in absentia, although this had frequently been allowed in the past, and in fact had been specifically permitted in a previous law. This was an obvious blow at Caesar's plans after his term in Gaul expired. Finally, in 51 B.C.E., Pompey made it clear that Caesar would not be permitted to stand for Consul unless he turned over control of his armies. This would, of course, leave Caesar defenseless before his enemies. As Cicero sadly noted, Pompey had begun to fear Caesar. Pompey had been diminished by age, uncertainty, and the harassment of being the chosen tool of a quarreling Optimate oligarchy. The coming conflict was inevitable.[6]

Civil War and assassination

In the beginning, Pompey claimed he could defeat Caesar and raise armies merely by stamping his foot on the soil of Italy, but by the spring of 49 B.C.E., with Caesar crossing the Rubicon and his invading legions sweeping down the peninsula, Pompey ordered the abandonment of Rome. His legions retreated south towards Brundisium, where Pompey intended to find renewed strength by waging war against Caesar in the East. In the process, neither Pompey nor the Senate thought of taking the vast treasury with them, probably thinking that Caesar would not dare take it for himself. It was left conveniently in the Temple of Saturn when Caesar and his forces entered Rome.

Escaping Caesar by a hair in Brundisium, Pompey regained his confidence during the siege of Dyrrhachium, in which Caesar lost 1000 men. Yet, by failing to pursue at the critical moment of Caesar's defeat, Pompey threw away the chance to destroy Caesar's much smaller army. As Caesar himself said, "Today the enemy would have won, if they had had a commander who was a winner."[7]. According to Suetonius, it was at this point that Caesar said that "that man (Pompey) does not know how to win a war."[8] With Caesar on their backs, the conservatives led by Pompey fled to Greece. Caesar and Pompey had their final showdown at the Battle of Pharsalus in 48 B.C.E. The fighting was bitter for both sides but eventually was a decisive victory for Caesar. Like all the other conservatives, Pompey had to run for his life. He met his wife Cornelia and his son Sextus Pompeius on the island of Mytilene. He then wondered where to go next. The decision of running to one of the eastern kingdoms was overruled in favor of Egypt.

After his arrival in Egypt, Pompey's fate was decided by the counselors of the young king Ptolemy XIII. While Pompey waited offshore for word, they argued the cost of offering him refuge with Caesar already en route for Egypt. It was decided to murder Caesar's enemy to ingratiate themselves with him. On September 28, a day short of his 58th birthday, Pompey was lured toward a supposed audience on shore in a small boat in which he recognized two old comrades-in-arms, Achillas and Lucius Septimius. They were to be his assassins. While he sat in the boat, studying his speech for the king, they stabbed him in the back with sword and dagger. After decapitation, the body was left, contemptuously unattended and naked, on the shore. His freedman, Philipus, organized a simple funeral pyre from the broken ship's timbers and cremated the body.

Caesar arrived a short time afterward. As a welcoming present, he received Pompey's head and ring in a basket. However, he was not pleased in seeing his rival, a consul of Rome and once his ally and son-in-law, murdered by traitors. When a slave offered him Pompey's head, "he turned away from him with loathing, as from an assassin; and when he received Pompey's signet ring on which was engraved a lion holding a sword in his paws, he burst into tears" (Plutarch, Life of Pompey 80). He deposed Ptolemy XIII, executed his regent Pothinus, and elevated Ptolemy's sister Cleopatra VII to the throne of Egypt. Caesar gave Pompey's ashes and ring to Cornelia, who took them back to her estates in Italy.

Marriages and offspring

- First wife, Antistia

- Second wife, Aemilia Scaura (Sulla's stepdaughter)

- Third wife, Mucia Tertia (whom he divorced for adultery, according to Cicero's letters)

- Fourth wife, Julia (daughter of Caesar)

- Fifth wife, Cornelia Metella (daughter of Metellus Scipio)

Chronology of Pompey's life and career

- 106 B.C.E. September 29 – born in Picenum

- 83 B.C.E. – aligns with Sulla, after his return from the Mithridatic War against king Mithridates IV of Pontus; marriage to Aemilia Scaura

- 82–81 B.C.E. – defeats Gaius Marius's allies in Sicily and Africa

- 76–71 B.C.E. – campaign in Hispania against Sertorius

- 71 B.C.E. – returns to Italy and participates in the suppression of a slave rebellion lead by Spartacus; second triumph

- 70 B.C.E. – first consulship (with M. Licinius Crassus)

- 67 B.C.E. – defeats the pirates and goes to Asia province

- 66–61 B.C.E. – defeats king Mithridates of Pontus; end of the Third Mithridatic War

- 64–63 B.C.E. – Pompey's March through Syria, the Levant, and Palestine

- 61 B.C.E. September 29 – third triumph

- 59 B.C.E. April – the first triumvirate is constituted; Pompey allies to Julius Caesar and Licinius Crassus; marriage to Julia (daughter of Julius Caesar)

- 58–55 B.C.E. – governs Hispania Ulterior by proxy, construction of Pompey's Theater

- 55 B.C.E. – second consulship (with M. Licinius Crassus)

- 54 B.C.E. – Julia, dies; the first triumvirate ends

- 52 B.C.E. – Serves as sole consul for intercalary month[9], third ordinary consulship with Metellus Scipio for the rest of the year; marriage to Cornelia Metella

- 51 B.C.E. – forbids Caesar (in Gaul) to stand for consulship in absentia

- 49 B.C.E. – Caesar crosses the Rubicon River and invades Italy; Pompey retreats to Greece with the conservatives

- 48 B.C.E. – Pompey is assassinated in Egypt.

Legacy

To the historians of his own and later Roman periods, the life of Pompey was simply too good to be true. No more satisfying historical model existed than the great man who, achieving extraordinary triumphs through his own efforts, yet fell from power and influence and, in the end, was murdered through treachery.

He was a hero of the Republic, who seemed once to hold the Roman world in his palm only to be brought low by his own poor judgment as well as by Caesar. Pompey was idealized as a tragic hero almost immediately after Pharsalus and his murder: Plutarch portrayed him as a Roman Alexander the Great, pure of heart and mind, destroyed by the cynical ambitions of those around him. Pompey indeed followed Alexander's footsteps and conquering much of the same territory, including Palestine. Much of what Pompey did set out, says Leach, to emulate Alexander.[10] Perhaps Palestine would have fallen to Rome sooner or later but it might have managed to become a client state instead, or even avoided integration into the Roman space. It was because Rome ruled Palestine that Jesus was born in Bethlehem because Mary and Joseph had to register there during an official census. It was because travel was possible across the Roman world that Christianity was able to spread as easily and quickly as it did.

Nonetheless, as a result of Pompey's Eastern campaign, the Middle East and the North Mediterranean zones became politically integrated. Culture, religion, philosophy and ideas began to flow in both directions. Links already existed between the Middle East and the Greek-Roman world but Pompey's conquests made new transport and communication channels possible. In the long term, this contributed to the way that people have befitted and learned from other cultures and civilizations, so that humanity become more inter-dependent and inter-connected. Having annexed what he described as the "outermost province" Pompey said that this was now "the most central one."[11] He not only conquered cities but rebuilt them, re-populated them, "instructed them" in Roman law and, says Archbishop Ussher, "ordained a commonwealth for them."[12] We know that Pompey saw establishing law and order as an imperial responsibility. We also know that he was interested in the cultures he encountered; Leach says that he was accompanied by "at least two men for the express purpose of collecting and recording ... discoveries."[10] He refers to botanical, geographical and medical knowledge. Extending "the boundaries of knowledge" was as important for Pompey as playing "power-politics". He consciously emulated "his boyhood hero." Leach also suggests that Pompey was influenced by Alexander's "attitude towards provincials" which had challenged the accepted wisdom that they were inferior; this had "found expression in Alexander's efforts to unite Greek and Persian in his new empire on equal terms." Thus Pompey's "humane and thoughtful treatment of enemies." "More than most Romans of his class and time" Pompey "tried to understand non-Romans" and counted among his friends "Greeks and freedmen to whom he turned for advice."[13]

Pompey in literature and the arts

The historical character of Pompey plays a prominent role in several books from the Masters of Rome series of historical novels by Australian author Colleen McCullough.[14]

Pompey's rivalry with Julius Caesar supports the plot in George Bernard Shaw's Caesar and Cleopatra (play).[15]

Pompey's porch, theatre, and entry into Rome are portrayed in Shakespeare's Julius Caesar. The insurrection group led by Brutus somewhat represents Pompey's "party".[16]

Pompey's entry into Jerusalem and the desecration of the Temple is depicted in the opening scene of Nicholas Ray's biblical epic King of Kings. Pompey is played by Conrado San Martín.[17]

Pompey is one of the key antagonists in the fourth season of Xena: Warrior Princess, portrayed by Australian actor Jeremy Callaghan. In the series, Pompey is beheaded by Xena in battle who then gives the head to Brutus to return to Julius Caesar, telling Brutus to claim Pompey's death for himself without mentioning her role.[18]

A fictionalized Gnaeus Pompey Magnus also plays a key role in the first season of the HBO/BBC television series Rome], where he is played by Kenneth Cranham.[19]

In the second episode of Ancient Rome: The Rise and Fall of an Empire, Pompey is portrayed by John Shrapnel. The episode follows Caesar's campaign against the Republic, whose army is led by Pompey.[20]

An opera seria composed during the baroque era, Handel's Giulio Cesare, is based on Cesar’s reaction to Pompey's assassination (since the opera begins after the murder has occurred, Pompey never actually appears as a character - only his severed head when presented to the horrified Cesare). Typically, works composed in the genre of opera seria were intended to present lessons of morality while depicting aristocracy in a flattering light. In the case of Handel's Giulio Cesare, the Roman emperor prevails in the administration of justice against the evil Tolomeo (Ptolemy).[21]

Pompey features as the main character and is held as a tragic hero in Lucan's Civil War the second most famous Roman heroic epic.[22] Shakespeare ironically referred to Pompey the Great in Measure for Measure.[23] A fictionalized depiction of Pompey's relationship with Cicero can be seen in Imperium, a novel by Robert Harris.[24]

Notes

- ↑ James Ussher, Larry Pierce, and Marion Pierce, The Annals of the World (Green Forest, AR: Master Books, 2006, ISBN 9780890515105), 599.

- ↑ In a story recorded by Valerius Maximus, the orator Helvius Mancia calls Pompey adulescentulus carnifex (which could be translated as both "youthful executioner" and "murderous youngster") in reference to his extrajudicial executions of Sulla's adversaries. Eyben, 1993, page 64.

- ↑ William Smith, A Dictionary of Greek and Roman Biography and Mythology (London, UK: J. Murray, 1880), 482.

- ↑ Flavius Josephus and William Whiston, The works of Flavius Josephus, the learned and authentic Jewish historian, and celebrated warrior. To which is added, three dissertations, concerning Jesus Christ, John the Baptist, James the Just, God's command to Abraham, etc. (Halifax, UK: Milner and Sowerby, 1864), 302.

- ↑ Ussher, Pierce, and Pierce, 2006, 599.

- ↑ Many historians have suggested that Pompey was, in spite of everything, politically unaware of the fact that the Optimates, including Cato, were merely using him against Caesar so that, with Caesar destroyed, they could then dispose of him.

- ↑ Plutarch, Stadter, and Waterfield, 1999, 335.

- ↑ Suetonius, Robert Graves, and J.B. Rives, The Twelve Caesars (London, UK: Penguin, 2007, ISBN 9780140455168), 17.

- ↑ Abbott, 114.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Leach, 1978, 78.

- ↑ Ussher, Pierce, and Pierce, 2006, 599.

- ↑ Ussher, Pierce, and Pierce, 2006, 597.

- ↑ Leach, 1978, 79.

- ↑ Colleen McCullough, Fortune's Favourites (London, UK: Century 1993, ISBN 9780712638500); Colleen McCullough, Caesar: Let the Dice Fly (New York, NY: W. Morrow, 1997, ISBN 9780688093723).

- ↑ Bernard Shaw and Dan H. Laurence, Caesar and Cleopatra: A History (New York, NY: Penguin Books, 2006, ISBN 9780143039778).

- ↑ William Shakespeare and Oliver Arnold, William Shakespeare's Julius Caesar (New York, NY: Longman, 2009, ISBN 9780321209436).

- ↑ King of Kings (1961). Internet Movie Database. Directed by Nicholas Ray. Screenplay by Philip Yordan. Retrieved August 6, 2019.

- ↑ Robert Tapert, Lucy Lawless, and Renee O'Connor, Xena, Warrior princess. Season Four (Troy, MI: Distributed by Anchor Bay Entertainment, 2004).

- ↑ Robert A. Papazian, Marco Valerio Pugini, Michael Apted, Bruno Heller, Kevin McKidd, Ray Stevenson, Ciaran Hinds, et al. Rome. First season (New York, NY: HBO Video, 2006, ISBN 9780783135991).

- ↑ "Ancient Rome: The Rise and Fall of an Empire" Caesar (2006). Internet Movie Database. Directed by Nick Green. Written by Jeremy Hylton Davis and James Wood. Retrieved August 6, 2019.

- ↑ George Frideric Handel, Nicola Francesco Haym, Barbara Schlick, Jennifer Larmore, Bernarda Fink, Marianne Rørholm, Derek Lee Ragin, et al., Giulio Cesare (Arles, FR: Harmonia Mundi, 1991).

- ↑ Lucan and S.H. Braund, Civil war (Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 1999, ISBN 9780192839497).

- ↑ Lines for Pompey in Measure for Measure. Open Source Shakespeare. Retrieved August 6, 2019.

- ↑ Robert Harris, Imperium: A Novel of Ancient Rome (New York, NY: Simon & Schuster, 2006, ISBN 9780743266031).

References

ISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Eyben, Emiel. Restless Youth in Ancient Rome. London, UK: Routledge, 1993. ISBN 9780415043663.

- Goldsworthy, Adrian Keith. In the Name of Rome: The Men who Won the Roman Empire. London, UK: Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 2003. ISBN 9780297846666.

- Harris, Robert. Imperium: A Novel of Ancient Rome. New York, NY: Simon & Schuster, 2006. ISBN 9780743266031.

- Langguth, A.J. A Noise of War: Caesar, Pompey, Octavian, and the Struggle for Rome. New York, NY: Simon & Schuster, 1994. ISBN 9780671708290.

- Leach, John. Pompey the Great. London, UK: Croom Helm, 1978. ISBN 9780847660353.

- McCullough, Colleen. Fortune's Favourites. London, UK: Century, 1993. ISBN 9780712638500.

- McCullough, Colleen. Caesar: Let the Dice Fly. New York, NY: W. Morrow, 1997. ISBN 9780688093723.

- Plutarch, John Dryden trans. Pompey. Boston, MA: MIT, 1932. Retrieved May 12, 2015.

- Plutarch, Philip A. Stadter, and Robin Waterfield. Roman Lives: A Selection of Eight Roman Lives. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 1999. ISBN 9780192825025.

- Seager, Robin. Pompey the Great: A Political Biography. Oxford, UK: Blackwell Pub., 2002. ISBN 9780631227205.

- Shakespeare, William, and Oliver Arnold. William Shakespeare's Julius Caesar. New York, NY: Longman, 2009. ISBN 9780321209436.

- Shaw, Bernard, and Dan H. Laurence. Caesar and Cleopatra: A History. New York, NY: Penguin Books, 2006. ISBN 9780143039778.

- Smith, William. A Dictionary of Greek and Roman Biography and Mythology. London, UK: J. Murray, 1880.

- Southern, Pat. Pompey the Great. Stroud, UK: Tempus, 2002. ISBN 9780752425214.

- Southern, Pat, and Karen R. Dixon. The Late Roman Army. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1996. ISBN 9780300068436.

- Suetonius, Robert Graves, and J.B. Rives. The Twelve Caesars. London, UK: Penguin, 2007. ISBN 9780140455168.

- Ussher, James, Larry Pierce, and Marion Pierce. The Annals of the World. Green Forest, AR: Master Books, 2006. ISBN 9780890515105.

External links

All links retrieved November 24, 2022.

- Pompey "the Great" entry in historical sourcebook by Mahlon Smith.

- Pompey's Siege of Jerusalem Livius.org.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.

↧ Download as ZWI file | Last modified: 02/04/2023 05:09:24 | 22 views

☰ Source: https://www.newworldencyclopedia.org/entry/Pompey | License: CC BY-SA 3.0

ZWI signed:

ZWI signed:

KSF

KSF