Tammany Hall

From Nwe

From Nwe

Tammany Hall was the Democratic Party political machine that played a major role in controlling New York City politics from the 1790s to the 1960s. It usually controlled Democratic Party nominations and patronage in Manhattan from the mayoral victory of Fernando Wood in 1854 to the election of Fiorello H. LaGuardia in 1934, then weakened and collapsed.

Tammany Hall is an example of how political parties, because they control who can and who can not stand for office with a realistic chance of success, exercise considerable power within the political process. Some may think that they exercise too much influence even when the nomination process is conducted with honesty and integrity but as long as the political system is a party-political system, with parties forming administrations, this will remain a reality. Democacy is stronger, however, when Tammany Hall type mechanisms do not commit abuses. Its decline and demise benefited American democracy.

History

1790-1850

The Tammany Society was founded in the 1780s. The name "Tammany" comes from Tamanend, a Native American chief of the Lenape. He was best known as a lover of peace and played a prominent role in establishing peaceful relations between Native American peoples and English settlers during the establishment of Philadelphia. The society adopted many Native American words and customs, going so far as to call its hall a wigwam, although Tammany Hall was a far cry from the modest domed shaped single room dwelling.

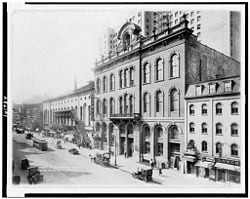

By 1798 the society's activities had grown increasingly politicized and eventually Tammany, led by Aaron Burr, a Revolutionary War hero and third vice president of the United States, emerged as the center for Jeffersonian Republican politics in the city. Burr built the Tammany Society into a political machine for the election of 1800, in which he was elected vice president. Without Tammany, historians believe, President John Adams might have won New York State's electoral votes and won reelection. In 1830, the Society's headquarters were established on West 14th Street in a building called Tammany Hall, and thereafter the name of the building and the group was synonymous.

After 1839, Tammany became the city affiliate of the Democratic Party, emerging as the controlling interest in New York City elections after Andrew Jackson's. In the 1830s, the Loco-Focos, a radical faction of the Democratic Party in existence from 1835-1840s, appealed to the working man of the time and was created as a protest to Tammany Hall.

Throughout the 1830s and 1840s, the society expanded its political control even further by earning the loyalty of the city's ever-expanding immigrant community, a task that was accomplished by helping newly-arrived foreigners obtain jobs, a place to live, and even citizenship so that they could vote for Tammany candidates in city and state elections. The mass immigrant constituency primarily functioned as a base of political capital. The "ward boss," who was the person wielding power over a political region, served as the local vote gatherer and provider of patronage. New York City used the word "ward" to designate its smallest political units from 1686-1938.

The Irish

Tammany is forever linked with the rise of the Irish in American politics. Beginning in 1846, large numbers of Irish Catholics began arriving in New York. Equipped with knowledge of the English language, very tight loyalties, a genius for politics, and what critics said was a propensity to use violence to control the polls, the Irish quickly dominated Tammany. In exchange for votes, they were provided with money and food. From 1872 onward, Tammany had an Irish "boss." They played an increasingly important role in state politics, supporting one candidate and feuding with another. The greatest success came in 1928 when a Tammany hero, New York governor Al Smith, won the Democratic presidential nomination.

Tweed Machine

By 1854, Tammany's lineage and support from immigrants made it a powerful force in New York politics. Tammany controlled businesses, politics and sometimes law enforcement. Businesses would give gifts to their workers and in exchange, tell the workers to vote for the politicians that were supported by Tammany. In 1854, the society elected its first New York City mayor. Tammany's "bosses" (called the "Grand Sachem") and their supporters enriched themselves by illegal means.

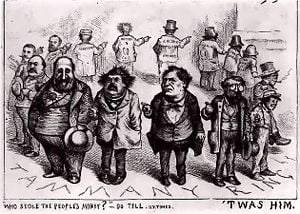

The most infamous boss of all was William M. "Boss" Tweed. Tweed's control over the Tammany Hall machine allowed him to win election to the New York State Senate. His official positions included membership on the city board of supervisors, chairman of the state finance committee and school commissioner to name a few. His political career ended when he became mired in corruption, and he went to prison along with his partner Francis I. A. Boole, after his ousting at the hands of a reform movement led by New York's Democratic governor Samuel J. Tilden in 1872.

In 1892, a Protestant minister, Charles Henry Parkhurst, made a widely-heard denunciation of Tammany Hall. This led to a grand jury investigation and the appointment of the Lexow Committee, a state probe into police corruption in New York City and was named for State Senator Clarence Lexow. The election of a reform mayor followed in 1894.

1890-1950

Despite occasional defeats, Tammany was consistently able to survive and prosper; it continued to dominate city and even state politics. Under leaders like John Kelly and Richard Croker, it controlled Democratic politics in the city. Tammany opposed William Jennings Bryan in 1896.

In 1901, anti-Tammany forces elected a reformer, Republican Seth Low, to become mayor. From 1902 until his death in 1924, Charles F. Murphy was Tammany's boss. In 1932, the machine suffered a dual setback when Mayor James Walker was forced from office and reform-minded Democrat Franklin Delano Roosevelt was elected president. Roosevelt stripped Tammany of its federal patronage—much expanded because of the New Deal—and handed city patronage to Ed Flynn, boss of the Bronx. Roosevelt helped Republican Fiorello H. LaGuardia become mayor on a Fusion ticket (where two or more political parties support a common candidate), thus removing even more patronage from Tammany's control.

For its power, Tammany depended on government contracts, jobs, patronage, corruption and ultimately the ability of its leaders to swing the popular vote. The last element weakened after 1940 with the decline of relief programs like Works Progress Administration Which was created on May 6, 1935 by presidential order. It was the largest New Deal agency employing millions. It provided jobs and income to the unemployed during the Great Depression along with the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC). This organization was a work relief program for young men from unemployed families and established on March 19, 1933.

Congressman Christopher "Christy" Sullivan was one of the last "bosses" of Tammany Hall before its collapse. Tammany never recovered, but it staged a small scale comeback in the early 1950s under the leadership of Carmine DeSapio, who succeeded in engineering the elections of Robert Wagner, Jr. as mayor in 1953 and Averill Harriman as state governor in 1954, while simultaneously blocking his enemies, especially Franklin D. Roosevelt, Jr. in the 1954 race for state attorney general.

Eleanor Roosevelt organized a counterattack with Herbert Lehman and Thomas Finletter to form the New York Committee for Democratic Voters, a group dedicated to fighting Tammany. In 1961, the group helped remove DeSapio from power. The once-mighty Tammany political machine, now deprived of its leadership, quickly faded from political importance and by the mid-1960s, it ceased to exist. The last building to serve as the physical Tammany Hall, on Union Square, is now home to the New York Film Academy. A large decorated flagpole base within Union Square Park is dedicated to Charles F. Murphy.

Leaders

| 1797 | – | 1804 | Aaron Burr |

| 1804 | – | 1814 | Teunis Wortmann |

| 1814 | – | 1817 | George Buckmaster |

| 1817 | – | 1822 | Jacob Barker |

| 1822 | – | 1827 | Stephen Allen |

| 1827 | – | 1828 | Mordecai M. Noah |

| 1828 | – | 1835 | Walter Bowne |

| 1835 | – | 1842 | Isaac Varian |

| 1842 | – | 1848 | Robert H. Morris |

| 1848 | – | 1850 | Isaac V. Fowler |

| 1850 | – | 1856 | Fernando Wood |

| 1857 | – | 1858 | Isaac V. Fowler |

| 1858 | Fernando Wood | ||

| 1858 | – | 1859 | William M. Tweed and Isaac V. Fowler |

| 1859 | – | 1867 | William M. Tweed and Richard B. Connolly |

| 1867 | – | 1871 | William M. Tweed |

| 1872 | John Kelly and John Morrissey | ||

| 1872 | – | 1886 | John Kelly |

| 1886 | – | 1902 | Richard Croker |

| 1902 | Lewis Nixon | ||

| 1902 | Charles F. Murphy, Daniel F. McMahon, and Louis F. Haffen | ||

| 1902 | – | 1924 | Charles F. Murphy |

| 1924 | – | 1929 | George W. Olvany |

| 1929 | – | 1934 | John F. Curry |

| 1934 | – | 1937 | James J. Dooling |

| 1937 | – | 1942 | Christopher D. Sullivan |

| 1942 | Charles H. Hussey | ||

| 1942 | – | 1944 | Michael J. Kennedy |

| 1944 | – | 1947 | Edward V. Loughlin |

| 1947 | – | 1948 | |

| 1948 | – | 1949 | Hugo E. Rogers |

| 1949 | – | 1961 | Carmine G. DeSapio |

References

ISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Erie, Steven P. 1988. Rainbow's End: Irish-Americans and the Dilemmas of Urban Machine Politics, 1840-1985. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 1988. ISBN 978-0520061194

- LaCerra, Charles. Franklin Delano Roosevelt and Tammany Hall of New York. Lanham, MD: University Press of America, 1997. ISBN 978-0761808084

- Lash, Joseph P. Eleanor: The Years Alone. New York: W. W. Norton & Co., 1972. ISBN 0393073610

- Mandelbaum, Seymour J. Boss Tweed's New York. Chicago: I.R. Dee, 1965. ISBN 978-0929587202

- Ostrogorski, M. Democracy and the Party System in the United States. New York: Arno Press, 1974. ISBN 978-0405058882

- Riordon, William L. Plunkitt of Tammany Hall: A Series of Very Plain Talks on Very Practical Politics. New York: Dutton, 1963. ISBN 978-0525471189

External Links

All links retrieved January 19, 2020.

- The Questia Online Library: Fernando Wood: A Political Biography by Jerome Mushkat (1990)

- The Questia Online Library: The Last of the Big-Time Bosses: The Life and Times of Carmine de Sapio and the Rise and Fall of Tammany Hall by Warren Moscow (1971)

- Tammany Hall – U-S-History.com

- Tammany Hall Building Proposed as Historic Landmark – Gramercy Neighborhood Associates

- Thomas Nast Caricatures of Boss Tweed & Tammany Hall – Great Caricatures

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

- Tammany Hall history

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

- History of "Tammany Hall"

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.

↧ Download as ZWI file | Last modified: 02/03/2023 23:53:28 | 6 views

☰ Source: https://www.newworldencyclopedia.org/entry/Tammany_Hall | License: CC BY-SA 3.0

ZWI signed:

ZWI signed: KSF

KSF