Fjord

From Nwe

From Nwe

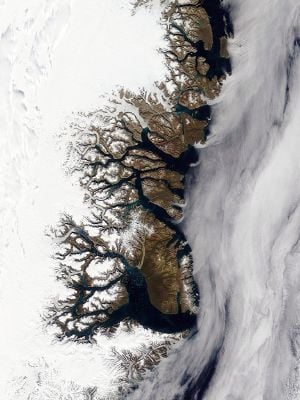

A fjord (or fiord) is a long, narrow deep inlet of the sea bordered by steep cliffs. Fjords commonly extend far inland and are extremely deep in their upper and middle reaches. Norway's Hardangerfjord drops to 2,624 feet (800 m) below sea level, while the depth of Sogn Fjord (also Norway) measures 4,290 feet (1,308 m) deep, and Canal Messier in Chile is 4,167 feet (1,270 m). The great depth of these submerged valleys is due to their glacial origins.

The seeds of a fjord are laid when a glacier cuts a U-shaped valley through abrasion of the surrounding bedrock by the sediment it carries. Many such valleys were formed during the recent ice age. At the end of such a period, the climate warms and glaciers retreat. Sea level rises due to an influx of water from melting ice sheets and glaciers around the world inundating the vacated valleys with seawater to form fjords.

Coasts having the most pronounced fjords include the west coast of Europe, the west coast of North America from Puget Sound to Alaska, the west coast of New Zealand, and the west coast of South America. Other areas which have lower altitudes and less pronounced glaciers also have fjords or fjord-like features. The only areas near a fjord where people can settle are deltas formed at the mouths of rivers.

The word "fjord" comes from Old Norse, fjörðr, meaning a "lake-like waterbody used for passage and ferrying."

Etymology

With Indo European origin (*prtús from *por- or *per) in the verb fare (travelling/ferrying), the Norse noun substantive fjörðr means a "Lake-like" waterbody used for passage and ferrying.

The Scandinavian Fjord is the origin for similar European words: Icelandic fjörður, Swedish fjärd (for Baltic waterbodies), English ford, Scottish firth, and is related to: Greek poros, Latin portus, German Furt.

As a loanword from Norwegian, it is the only word in the English language to begin with the digraph fj.

Use of the word fjord (including the eastern Scandinavian form fjärd) is more general in the Scandinavian languages than in English. In Scandinavia, fjord is used for a narrow inlet of the sea in Norway, Denmark and western Sweden, but this is not its only application. In Norway, the usage is closest to the Old Norse, with fjord used for both a firth and for a long, narrow inlet. In eastern Norway, the term is also applied to long narrow freshwater lakes and sometimes even to rivers (in local usage, for instance in Flå in Hallingdal, the Hallingdal river is referred to as fjorden). In east Sweden, the name fjärd is used in a synonymous manner for bays, bights and narrow inlets on the Swedish Baltic Sea coast, and in most Swedish lakes. This latter term is also used for bodies of water off the coast of Finland where Finland Swedish is spoken. In modern Icelandic, fjörður is still used with the broader meaning of firth or inlet. In Finnish language, a word vuono is used although there is only one fjord in Finland.

The German use of the word Förde on sea-stretches on their Baltic Sea coastline, seems to indicate a common Germanic origin of the word. The landscape consists mainly of moraine heaps, and "real" fjords in the geological sense are not possible. Kieler Förde still fits the same criteria as other fjordnames further north, while others merely fits the description of bugt as used in Danish. One may therefore conclude that fjord was one of the names used by Germanic tribes to describe a sea-territory.

The name of Wexford in Ireland is originally derived from Waes Fjord ("inlet of the mud flats") in Old Norse, as used by the viking settlers—though the place does not have a fjord in the more narrow modern meaning.

Geology

The seeds of a fjord are laid when a glacier cuts a U-shaped valley through abrasion of the surrounding bedrock by the sediment it carries. Many such valleys were formed during the recent ice age. At the end of such a period, the climate warms and glaciers retreat. Sea level rises due to an influx of water from melting ice sheets and glaciers around the world inundating the vacated valleys with seawater to form fjords.

It is believed that the glaciers that formed in these valleys were so thick and heavy that they eroded the bottom of the valley far below sea level before they floated in the ocean water. After the glaciers melted, the waters of the sea invaded the valleys.

Glacial melting is also accompanied by a rebound in the earth's crust as the ice load is removed. In some cases this rebound may be faster than the sea level rise. Most fjords are, however, deeper than the adjacent sea; Sognefjord, Norway, reaches as much as 1,300 m (4,265 ft) below sea level. Fjords are often very deep in their upper and middle reaches, although they generally have a sill or rise at their mouth associated with the previous glacier's terminal moraine. These characteristics distinguish fjords from rias (such as the Bay of Kotor), which are drowned valleys flooded by the rising sea.

The walls of a fjord often rise vertically hundreds of feet at water's edge. There is not a "shore" where land and water meet, and the water's depth may be hundreds of feet deep at that point. A small stream can plunge hundreds of feet over the edge of the fjord, causing a waterfall. Some of the highest waterfalls in the world are fjord-waterfalls.

Fjords commonly contain winding channels and sharp corners. Often the valley is floored with glacial debris, extending inland into the mountains. Small glaciers may remain at the head of such a valley. It is common that, following the disappearance of ice, the river that formed the original valley reestablishes itself on the upper valley floor. A delta is then formed, which provide for the establishment of homes and farms.

Locations

The principal mountainous regions where fjords have formed are in the higher middle latitudes where, during the glacial period, many valley glaciers descended to the then-lower sea level. The fjords develop best in mountain ranges against which the prevailing westerly marine winds are orographically lifted over the mountainous regions, resulting in abundant snowfall to feed the glaciers. Hence coasts having the most pronounced fjords include the west coast of Europe, the west coast of North America from Puget Sound to Alaska, the west coast of New Zealand, and the west coast of South America. Other areas which have lower altitudes and less pronounced glaciers also have fjords or fjord-like features.

West coast of Europe

- Faroe Islands

- Norway

- Iceland

- Killary Harbour, Ireland

West coast of New Zealand

- Fiordland, in the southwest of the South Island of New Zealand

West coast of North America

- The coast of Alaska in the United States: Lynn Canal, Portland Canal, among others.

- British Columbia Coast, Canada: from the Alaskan Border to Indian Arm; Kingcome Inlet is a typical West Coast fjord.

West coast of South America

- Zona Austral, Chile

Other glaciated regions

Other regions have fjords, but many of these are less pronounced due to more limited exposure to westerly winds and less pronounced relief. Areas include:

- Europe

- North America

- Canada:

- Newfoundland & Labrador: Saglek Fjord, Nachvak Fjord, Hebron Fjord, and Bonne Bay in Gros Morne National Park

- Quebec's Saguenay River valley

- the Arctic Archipelago

- Greenland

- United States

- Somes Sound, Acadia National Park, Maine

- Canada:

- Arctic

- Arctic islands

- Antarctica

- particularly the Antarctic Peninsula

- Sub-antarctic islands

Extreme fjords

The longest fjords in the world are:

- Scoresby Sund in Greenland - 350 km (220 mi)

- Sognefjord in Norway - 203 km (126 mi)

- Hardangerfjord in Norway - 179 km (111 mi)

Deep fjords include:

- Skelton Inlet in Antarctica - 1,933 m (6,342 ft)

- Sognefjord in Norway - ~1,308 m (4,291 ft) (the mountains then rise to up to 1,000 m)

- Messier Channel in Chile, South America - 1,288 m (4,226 ft)

Even deeper is the Vanderford Valley (2,287 m or 7,503 ft), carved by the Antarctica's Vanderford Glacier. This undersea valley lies offshore, however, and is therefore not considered a fjord.

Fjord features and variations

Coral reefs

As recently as the year 2000, some of the world's largest coral reefs were discovered along the bottoms of the Norwegian fjords. These reefs were found in fjords stretching from north to south. The marine life on the reefs is believed to be one of the most important reasons that the Norwegian coastline is such a generous fishing ground.

The reefs are host to numerous lifeforms, such as plankton, coral, anemones, fish, several species of sharks, and many more one would expect to find on a reef. However most are specially adapted to life under the greater pressure of the water column above it, and the total darkness of the deep sea.

New Zealand's fiords are also host to deep sea corals, but a surface layer of dark fresh water allows these corals to grow in much shallower water than usual. An underwater observatory in Milford Sound allows tourists to view them without diving.

Skerries

In some places near the seaward margins of areas with fjords, the ice-scoured channels are so numerous and varied in direction that the rocky coast is divided into thousands of island blocks, some large and mountainous while others a merely rocky points or rock reefs, menacing navigation. These are called skerries. The term skerry is derived from the old Norse sker, which means a rock in the sea.

Skerries are most commonly formed at the outlet of fjords where submerged glacially formed valleys at right angles with the coast join with other cross valleys in a complex array. The island fringe of Norway is such a group of skerries (called a skjærgård); many of the cross fjords are so arranged that they parallel the coast and provide a protected channel behind an almost unbroken succession of mountainous islands and skerries. By this channel one can travel through a protected passage almost the entire 1,600 km route from Stavanger to North Cape, Norway. The Blindleia is a skerry-protected waterway that starts near Kristiansand in southern Norway, and continues past Lillesand. The Swedish coast along Bohuslän is likewise skerry guarded. The “inside passage” provides a similar route from Seattle, Washington to Skagway, Alaska. Yet another such skerry protected passage extends from the Straits of Magellan north for 800 km.

False fjords

The differences in usage between the English and the Scandinavian languages have contributed to confusion in the use of the term fjord. Bodies of water which are clearly fjords in Scandinavian languages are not considered fjords in English; similarly bodies of water which would clearly not be fjords in the Scandinavian sense have been named or suggested to be fjords. Examples of this confused usage follow.

The Gulf of Kotor in Montenegro has been suggested by some to be a fjord, but is in fact a drowned river canyon or ria. Similarly the Lim bay in Istria, Croatia, is sometimes called "Lim fjord" although it is not actually a fjord carved by glacial erosion but instead a ria dug by the river Pazinčica. The Croats call it Limski kanal which does not transliterate precisely to the English equivalent either.

Limfjord in the north of Denmark is a fjord in the Scandinavian sense, but is not a fjord in the English sense. In English it would be called a channel, since it separates the island of Vendsyssel-Thy from the rest of Jutland.

While the long fjord-like bays of the New England coast are sometimes referred to as "fiards," the only glacially-formed fjord-like feature in New England is Somes Sound in Maine.

The fjords in Finnmark (Norway), which are fjords in the Scandinavian sense of the term, are considered by some to be false fjords. Although glacially formed, most Finnmark fjords lack the classic hallmark steep-sided valleys of the more southerly Norwegian fjords since the glacial pack was deep enough to cover even the high grounds when they were formed.

Some Norwegian freshwater lakes which have formed in long glacially carved valleys with terminal moraines blocking the outlet follow the Norwegian naming convention; they are named fjords.

Outside of Norway, the three western arms of New Zealand's Lake Te Anau are named North Fiord, Middle Fiord and South Fiord. Another freshwater "fjord" in a larger lake is Baie Fine, located on the northeastern coast of Georgian Bay of Lake Huron in Ontario. Western Brook Pond, in Newfoundland's Gros Morne National Park, is also often described as a fjord, but is actually a freshwater lake cut off from the sea, so is not a fjord in the English sense of the term. Such lakes are sometimes called "fjord lakes." Okanagan Lake was the first North American lake to be so described, in 1962. The bedrock there has been eroded up to 650 m below sea level, which is 2000 m below the surrounding regional topography—deeper than the Grand Canyon.[1]

Notes

- ↑ Hugh Nasmith, Late Glacial History and Surficial Deposits of the Okanagan Valley (A. Sutton, 1962).

References

ISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Cooper, Alfred Heaton. The Norwegian Fjords: Painted and Described. Legare Street Press, 2022. ISBN 978-1015746091

- Hurdle, Burton G. The Nordic seas. New York: Springer-Verlag, 1986. ISBN 978-0387962412

- Nasmith, Hugh. Late Glacial History and Surficial Deposits of the Okanagan Valley. A. Sutton, 1962. ASIN B000XG7KZO

- Roy, Iain. Beyond the imaginary gates: journeys in the fjord region of north-east Greenland. Stockport: Dewi Lewis, 2004. ISBN 978-1904587064

External links

All links retrieved January 22, 2023.

- Whales probe Arctic fjord's secrets BBC

- Norwegian fjords

- Fjord National Geographic Society

- Norway's Most Famous Fjords Visit Norway

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.

↧ Download as ZWI file | Last modified: 02/04/2023 01:12:18 | 8 views

☰ Source: https://www.newworldencyclopedia.org/entry/Fjord | License: CC BY-SA 3.0

ZWI signed:

ZWI signed:

KSF

KSF