Betrothal

From Nwe

From Nwe Betrothal is a formal state of engagement to be married. Historically betrothal was a formal contract, blessed or officiated by a religious authority. Formal betrothal is no longer common beyond some Arab cultures, in Judaism, and in Hinduism. In Jewish weddings the betrothal is called קידושין (in modern Hebrew, קידושים) and is part of the Jewish wedding ceremony.

For most cultures, an "engagement" period takes place prior to the wedding ceremony, during which time the couple make preparations for their marriage. The start of the engagement is signified by the giving of an engagement ring by the man to the woman. Wearing such a ring indicates to society that she has promised to marry, committing herself to her future spouse, but that they have not yet formalized their relationship in marriage. Unlike a formal betrothal, however, such an engagement is not legally binding, and the couple may "break off" their engagement with only emotional consequences. Still, betrothal in whatever form it has developed in contemporary times maintains a significant and meaningful role.

Terminology

The word betrothal comes from the Old English treowðe meaning "truth, a pledge."[1] The word is often used interchangeably with "engaged." Betrothal, however, often refers to agreements involving not only the couple but their families; the concept sometimes has a connotation of arranged marriage. Furthermore, betrothals, though they can be broken, often have binding legal implications lacking in engagements.

Fiancé(e)

A man who is engaged to be married is called his partner's fiancé; a woman similarly engaged is called her partner's fiancée. These words are pronounced identically in English; the separate feminine form exists because of the inflectional morphology of grammatical gender in French, where the term originated.

Proposal

Engagement is most often initiated by a proposal of marriage, or simply a proposal. The proposal often has a ritual quality, involving the presentation of the engagement ring and a formalized asking of a question such as "Will you marry me?" In a heterosexual relationship, the man traditionally proposes to the woman, but this is no longer universal.

In Ireland, February 29 is said to be the one day (coming round only once every four years) when a woman can propose to her partner. In the United States, it is traditional to call friends and family members immediately after the proposal has been accepted.

Process

Typical steps of a betrothal were:

- Selection of the bride

- usually done by the couple's families, possibly involving a matchmaker, with bride and groom having little or no input,

- this is no longer practiced except in some cultures (such as in Israel, India), and most of these have a requirement that the bride be allowed at least veto power

- Negotiation of bride price or dowry

- in modern practice these have been reduced to the symbolic engagement ring

- Blessing by clergy

- Exchange of Vows and Signing of Contracts

- often one of these is omitted

- Celebration

The exact duration of a betrothal varies according to culture and the participants’ needs and wishes. For adults, it may be anywhere from several hours (when the betrothal is incorporated into the wedding day itself) to a period of several years. A year and a day are common in neo-pagan groups today. In the case of child marriage, betrothal might last from infancy until the age of marriage.

The responsibilities and privileges of betrothal vary. In most cultures, the betrothed couple is expected to spend much time together, learning about each other. In some historical cultures (including colonial North America), the betrothal was essentially a trial marriage, with marriage only being required in cases of conception of a child. In almost all cultures there is a loosening of restrictions against physical contact between partners, even in cultures which would normally otherwise have strong prohibitions against it. The betrothal period was also considered to be a preparatory time, in which the groom would build a house, start a business, or otherwise prove his readiness to enter adult society.

In medieval Europe, in canon law, a betrothal could be formed by the exchange of vows in the future tense ("I will take you as my wife/husband," instead of "I take you as my wife/husband"), but sexual intercourse consummated the vows, making a binding marriage rather than a betrothal. Although these betrothals could be concluded with only the vows spoken by the couple, they had legal implications; Richard III of England had his older brother's children declared illegitimate on the grounds their father had been betrothed to another woman when he married their mother.

A betrothal is considered to be a "semi-binding" contract. Normal reasons for invalidation of a betrothal include:

- revelation of a prior commitment or marriage,

- evidence of infidelity,

- failure to conceive (in 'trial marriage' cultures),

- failure of either party to meet the financial and property stipulations of the betrothal contract.

Normally a betrothal can also be broken at the behest of either party, though some financial penalty (such as forfeit of the bride price) usually will apply.

Orthodox churches

In the Eastern Orthodox and Greek-Catholic Churches, the Rite of Betrothal is traditionally be performed in the narthex (entranceway) of the church, to indicate the couple's first entrance into the married estate. The priest blesses the couple and gives them lit candles to hold. Then, after a litany, and a prayer at which everyone bows, he places the bride's ring on the ring finger of the groom's right hand, and the groom's ring on the bride's finger. The rings are then exchanged three times, either by the priest or by the best man, after which the priest says a final prayer.

Originally, the betrothal service would take place at the time the engagement was announced. In recent times, however, it tends to be performed immediately before wedding ceremony itself. It should be noted that the exchange of rings is not a part of the wedding service in the Eastern Churches, but only occurs at the betrothal.

Judaism

In Judaism, the Mishna describes three ways of contracting betrothal (tractate Kiddushin 1:1):

- With money (as when a man hands a woman an object of value, such as a ring or a coin, for the purpose of contracted marriage, and in the presence of two witnesses, and she actively accepts);

- Through a shtar, a contract containing the betrothal declaration phrased as "through this contract"; or

- By sexual intercourse with the intention of creating a bond of marriage, a method strongly discouraged by the rabbinic sages and intended only for levirate marriages.

Today only the betrothal ceremony involving the object of value (the equivalent of "with money"), almost always a ring, is practiced, but the others may be fallen back upon should a halachic dispute occur.

As part of the marriage ceremony the woman accepts a ring (or something of value) from the man, accepting the terms of the marriage. At the giving of the ring the groom makes a declaration "You are consecrated to me, through this ring, according to the religion of Moses and Israel." Traditionally there is no verbal response on the part of the bride. She accepts the ring on her finger, and closes her hand, signifying acceptance.

Traditions

An engagement is an agreement or promise to marry, and also refers to the time between proposal and marriage. During this period, a couple is said to be affianced, engaged to be married, or simply engaged.

The engagement period

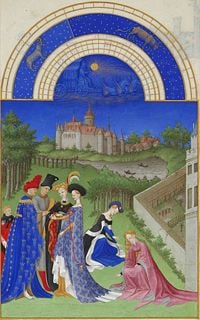

The concept of an engagement period may have begun in 1215 at the Fourth Lateran Council, headed by Pope Innocent III, which decreed that "marriages are to be ... announced publicly in the churches by the priests during a suitable and fixed time, so that if legitimate impediments exist, they may be made known."[2] The modern Western form of the practice of giving or exchanging engagement rings is traditionally thought to have begun in 1477 when Maximilian I, Holy Roman Emperor gave Mary of Burgundy a diamond ring as an engagement present.[3]

Engagement parties

Some, but not all, engagements are honored with an engagement party, often hosted by the bride's parents. It may be formal or informal, and is typically held between six months and a year before the wedding. Traditionally, engagement parties allowed the bride's parents to announce the upcoming marriage to friends and families. Today, such an event can either be an announcement or simply a celebration.

Engagement rings

In the United States, Canada, and the United Kingdom, an engagement ring is worn on the fourth finger of the left hand; the custom in Continental Europe and other countries is to wear it on the right hand. This tradition is thought to be from the Romans, who believed this finger to be the beginning of the vena amoris ("vein of love"), the vein that leads to the heart.

Romantic rings from the time of the Roman Empire and from as far back as 4 C.E. often resemble the Celtic Claddagh symbol (two hands clasping a heart) and so it is thought that this was used as some symbol of love and commitment between a man and a woman.

Handfasting

Handfasting is a ritual in which the couple's clasped hands are tied together by a cord or ribbon—hence the phrase "tying the knot." The tying of the hands may be done by the officiant of the ceremony, by the wedding guests, or by the couple themselves.

In Ireland and Scotland, during the early Christian period it was a form of trial marriage, often performed in rural areas when a priest was not available. The couple could form a temporary, trial marriage, and then be married "in the Church" the next time a priest visited their area. In some modern Neopagan groups, the ceremony has been reinterpreted to be a spiritual marriage, whether on a trial basis or as a permanent (even eternal) bond.

The tying together of the couple's hands was a part of the normal marriage ceremony in the time of the Roman Empire.[4] In the sixteenth century, the English cleric Myles Coverdale wrote in The Christen State of Matrymonye, that in that day, handfasting was still in use in some places, but was then separate from the Christian wedding rite performed in a church several weeks after the consummation of the marriage, which had already begun with the handfasting ritual. According to the Oxford English Dictionary, handfasting was then sometimes treated as a probationary form of marriage.

One historical example of handfastings as trial marriages is that of "Telltown marriages"—named for the year and a day trial marriages contracted at the yearly festival held in Telltown, Ireland. The festival took place every year at Lughnasadh (August 1), and the trial marriage would last until the next Lughnasadh festival. At that time, they were free to leave the union if they desired.

Modern usage

In the present day, some Neopagans practice this ritual. The marriage vows taken may be for "a year and a day," a lifetime, or "for all of eternity." Whether the ceremony is legal, or a private spiritual commitment, is up to the couple. Depending on the state where the handfasting is performed, and whether or not the officiant is a legally-recognized minister, the ceremony itself may be legally binding, or couples may choose to make it legal by also having a civil ceremony. Modern handfastings are performed for heterosexual or homosexual couples, as well as for larger groups in the case of polyamorous relationships.

As with many Neopagan rituals, some groups may use historically attested forms of the ceremony, striving to be as traditional as possible, while others may use only the basic idea of handfasting and largely create a new ceremony.

As many different traditions of Neopaganism use some variation on the handfasting ceremony, there is no universal ritual form that is followed, and the elements included are generally up to the couple being handfasted. In cases where the couple belong to a specific religious or cultural tradition, there may be a specific form of the ritual used by all or most members of that particular tradition. The couple may conduct the ceremony themselves or may have an officiant perform the ceremony. In some traditions, the couple may jump over a broom at the end of the ceremony. Some may instead leap over a small fire together. Today, some couples opt for a handfasting ceremony in place of, or incorporated into, their public wedding. As summer is the traditional time for handfastings, they are often held outdoors.

A corresponding divorce ceremony called a handparting is sometimes practiced, though this is also a modern innovation. In a Wiccan handparting, the couple may jump backwards over the broom before parting hands.

As with more conventional marriage ceremonies, couples often exchange rings during a handfasting, symbolizing their commitment to each other. Many couples choose rings that reflect their spiritual and cultural traditions, while others choose plainer, more conventional wedding rings.

Notes

- ↑ Betroth, Etymology Online. Retrieved September 4, 2007.

- ↑ The Canons of the Fourth Lateran Council, 1215, Medieval Source Book. Retrieved September 4, 2007.

- ↑ The History of the Engagement Ring, Royal Jewelers. Retrieved September 4, 2007.

- ↑ Historical Handfasting, Medieval Scotland. Retrieved September 4, 2007.

References

ISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Burkett, Larry. Money Before Marriage: A Financial Workbook for Engaged Couples. Moody Publishers, 1996. ISBN 0802463894

- Macomb, Sussanna. Joining Hands and Hearts: Interfaith, Intercultural Wedding Celebrations—A Practical Guide for Couples. Simon & Schuster Adult Publishing Group, 2002. ISBN 0743436989

- Yalomb, Marilyn. A History of the Wife. Harper Perennial, 2002. ISBN 0060931566

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.

↧ Download as ZWI file | Last modified: 02/04/2023 03:34:00 | 213 views

☰ Source: https://www.newworldencyclopedia.org/entry/Betrothal | License: CC BY-SA 3.0

ZWI signed:

ZWI signed:

KSF

KSF