Lekah Dodi

From Jewish Encyclopedia (1906)

From Jewish Encyclopedia (1906)

Lekah Dodi (

= "Come, my friend" [to meet the bride]):

= "Come, my friend" [to meet the bride]):

By: Cyrus Adler , Francis L. Cohen

The initial words of the refrain of a hymn for the service of inauguration of the Sabbath, written about the middle of the sixteenth century by Solomon ha-Levi Alḳabiẓ , who signed eight of its nine verses with his acrostic. The author draws much of his phraseology from Isaiah's prophecy of Israel's restoration, and six of his verses are full of the thoughts to which his vision of Israel as the bride on the great Sabbath of Messianic deliverance gives rise. It is practically the latest of the Hebrew poems regularly accepted into the liturgy, both in the southern use, which the author followed, and in the more distant northern rite.

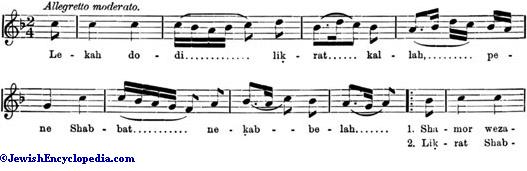

Ancient Moorish Melody.Its importance in the esteem of Jewish worshipers has led every cantor and choir-director to seek to devote his sweetest strains to the Sabbath welcomesong. Settings of "Lekah Dodi," usually of great expressiveness and not infrequently of much tenderness and beauty, are accordingly to be found in every published compilation of synagogal melodies. Among the Sephardic congregations, however, the hymn is universally chanted to an ancient Moorish melody of great interest, which is known to be much older than the text of "Lekah Dodi" itself. This is clear not only from internal evidence, but also from the rubric in old prayer-books directing the hymn "to be sung to the melody of 'Shubi Nafshi li-Menuḥayeki,'" a composition of Judah ha-Levi, who died nearly five centuries before Alḳabiẓ. In this rendering, carried to Palestine by Spanish refugees before the days of Alḳabiẓ, the hymn is chanted congregationally, the refrain being employed as an introduction only. But in Ashkenazic synagogues the verses are ordinarily chanted at elaborate length by the ḥazzan, and the refrain is properly used as a congregational response.

Old German and Polish Melodies.At certain periods of the year many northern congregations discard later compositions in favor of two simple older melodies singularly reminiscent of the folk-song of northern Europe in the century succeeding that in which the verses were written. The better known of these is an air, reserved for the 'Omer weeks between Passover and Pentecost, which has been variously described, because of certain of its phrases, as an adaptation of the famous political song "Lilliburlero" and of the cavatina in the beginning of Mozart's "Nozze di Figaro." But resemblances to German folk-song of the end of the seventeenth century may be found generally throughout the melody.

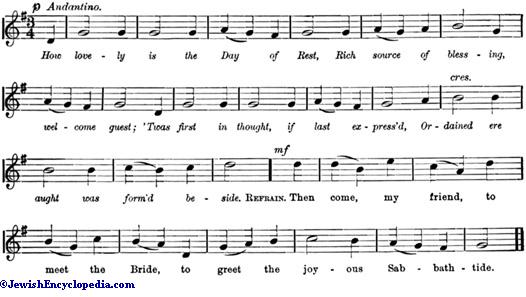

Less widely utilized in the present day is the special air traditional for the "Three Weeks" precedingthe Fast of Ab, although this is characterized by much tender charm absent from the melody of Eli Ẓiyyon , which more often takes its place. But it was once very generally sung in the northern congregations of Europe; and a variant was chosen by Benedetto Marcello for his rendition of Psalm xix. in his "Estro Poetico-Armonico" or "Parafrasi Sopra li Salmi" (Venice, 1724), where it is quoted as an air of the German Jews. Birnbaum ("Der Jüdische Kantor," 1883, p. 349) has discovered the source of this melody in a Polish folk-song, " Wezm ja Kontusz, Wezm," given in Oskar Kolbe's "Piesni Ludu Polskiego" (Warsaw, 1857). An old melody, of similarly obvious folk-song origin, was favored in the London Jewry a century ago, and was sung in two slightly divergent forms in the old city synagogues. Both of these forms are given by Isaac Nathan in his setting of Byron's "Hebrew Melodies" (London, 1815), where they constitute the air selected for "She Walks in Beauty," the first verses in the series. But the melody, which has nothing Jewish about it, was scarcely worth preserving; and it has since fallen quite out of use in English congregations and apparently elsewhere as well.

- Traditional settings: A. Baer, Ba'al Tefillah, Nos. 326-329, 340-343, Gothenburg, 1877, Frankfort, 1883;

- Cohen and Davis, Voice of Prayer and Praise, Nos. 18, 19a, and 19b, London, 1899;

- F. Consolo, Libro dei Canti d'Israele, part. i, Florence, 1892;

- De Sola and Aguilar, Ancient Melodies, p. 16 and No. 7, London, 1857;

- Israel, London, i. 82; iii. 22, 204;

- Journal of the Folk-Song Society, i., No. 2, pp. 33, 37, London, 1900. Translations, etc.: Israel, iii. 22;

- H. Heine, Werke, iii. 234, Hamburg, 1884;

- J. G. von Herder, Werke, Stuttgart, 1854;

- A. Lucas, The Jewish Year, p. 167, London, 1898.

Categories: [Jewish encyclopedia 1906]

↧ Download as ZWI file | Last modified: 09/04/2022 19:23:52 | 54 views

☰ Source: https://www.jewishencyclopedia.com/articles/9737-lekah-dodi.html | License: Public domain

ZWI signed:

ZWI signed: KSF

KSF