Indian Wars

From Nwe

From Nwe | Indian Wars in North America | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

An 1899 chromolithograph of U.S. cavalry pursuing American Indians, artist unknown |

|||||||

|

|||||||

| Combatants | |||||||

| Native Americans | Colonial America/United States of America | ||||||

Indian Wars is the name generally used in the United States to describe a series of conflicts between the colonial or federal government and the indigenous peoples. Although the earliest English settlers in what would become the United States often enjoyed peaceful relations with nearby tribes, as early as the Pequot War of 1637, the colonists were taking sides in military rivalries between Indian nations in order to assure colonial security and open further land for settlement. The wars, which ranged from the seventeenth-century (King Philip's War, King William's War, and Queen Anne's War at the opening of the eighteenth century) to the Wounded Knee massacre and "closing" of the American frontier in 1890, generally resulted in the opening of Native American lands to further colonization, the conquest of American Indians and their assimilation, or forced relocation to Indian reservations. Various statistics have been developed concerning the devastations of these wars on both the American and Indian nations. The most reliable figures are derived from collated records of strictly military engagements such as by Gregory Michno which reveal 21,586 dead, wounded, and captured civilians and soldiers for the period of 1850-1890 alone.[1] Other figures are derived from extrapolations of rather cursory and unrelated government accounts such as that by Russell Thornton who calculated that some 45,000 Indians and 19,000 whites were killed. This later rough estimate includes women and children on both sides, since noncombatants were often killed in frontier massacres.[2] Other authors have estimated the number killed to range from as low as 5,000 to as high as 500,000. What is not disputed is that the savagery from both sides of the war—the Indians' own methods of brutal warfare and the Americans destructive campaigns—was such as to be noted in every year in newspapers, historical archives, diplomatic reports and America’s own Declaration of Independence. ("… [He] has endeavoured to bring on the inhabitants of our frontiers, the merciless Indian Savages whose known rule of warfare, is an undistinguished destruction of all ages, sexes and conditions.")

The Indian Wars comprised a series of smaller battles and military campaigns. American Indians, diverse peoples with their own distinct tribal histories, were no more a single people than the Europeans. Living in societies organized in a variety of ways, American Indians usually made decisions about war and peace at the local level, though they sometimes fought as part of formal alliances, such as the Iroquois Confederation, or in temporary confederacies inspired by leaders such as Tecumseh. While the narrative of the fist Thanksgiving stresses harmony and friendship between the European settlers and the Indigenous peoples of the Americas, the subsequent history of settler-Indian relations told a different story. The high ideals of the American founding fathers stated that all men are born equal and free; unfortunately, these ideals were interpreted to exclude indigenous peoples; their lands were seized, their culture was denigrated, whole populations were forcibly re-settled and rights were violated. Only many decades later has the Native American view been considered. Encroaching white Americans were relentless in their attempts to destroy and dispell indigenous populations. Besides acts of warfare, many Native Americans died as a result of diseases transmitted by whites.

East of the Mississippi (1775–1842)

These are wars fought primarily by the newly established United States against the Native Americans until shortly before the Mexican-American War.

| Indian Wars East of the Mississippi |

|

American Revolutionary War

The American Revolutionary War was essentially two parallel wars: while the war in the East was a struggle against British rule, the war in the West was an "Indian War." The newly proclaimed United States competed with the British for the allegiance of Native American nations east of the Mississippi River. The colonial interest in westward settlement, as opposed to the British policy of maintaining peace, was one of the minor causes of the war. Most Native Americans who joined the struggle sided with the British, hoping to use the war to halt colonial expansion onto American Indian land. The Revolutionary War was "the most extensive and destructive" Indian war in United States history.[3]

Many native communities were divided over which side to support in the war. For the Iroquois Confederacy, the American Revolution resulted in civil war. Cherokees split into a neutral (or pro-U.S.) faction and the anti-U.S. faction that the Americans referred to as the Chickamaugas, led by Dragging Canoe. Many other communities were similarly divided.

Frontier warfare was particularly brutal, and numerous atrocities were committed on both sides. Both Euro-American and Native American noncombatants suffered greatly during the war, and villages and food supplies were frequently destroyed during military expeditions. The largest of these expeditions was the Sullivan Expedition of 1779, which destroyed more than 40 Iroquois villages in order to neutralize Iroquois raids in upstate New York. The expedition failed to have the desired effect: American Indian activity became even more determined.

Native Americans were stunned to learn that, when the British made peace with the Americans in the Treaty of Paris (1783), they had ceded a vast amount of American Indian territory to the United States without informing their Indian allies. The United States initially treated the American Indians who had fought with the British as a conquered people who had lost their land. When this proved impossible to enforce (the Indians had lost the war on paper, not on the battlefield), the policy was abandoned. The United States was eager to expand, and the national government initially sought to do so only by purchasing Native American land in treaties. The states and settlers were frequently at odds with this policy, and more warfare followed.[4]

Chickamauga Wars

These were an almost continuous series of frontier conflicts that began with Cherokee involvement in the American Revolutionary War and continued until late 1794. The so-called Chickamauga were those Cherokee, at first from the Overhill Towns and later from the Lower Towns, Valley Towns, and Middle Towns, who followed the war leader Dragging Canoe southwest, first to the Chickamauga (Chattanooga, Tennessee) area, then to the Five Lower Towns. There they were joined by groups of Muskogee, white Tories, runaway slaves, and renegade Chickasaw, as well as well over one hundred Shawnee, in exchange for whom a hundred Chickamauga-Cherokee warriors went north, along with another seventy a few years later. The primary objects of attack were the colonies along the Watauga, Holston, and Nolichucky rivers and in Carter's Valley in upper East Tennessee, as well as the settlements along the Cumberland River beginning with Fort Nashborough in 1780, even into Kentucky, plus against the colonies, later states, of Virginia, North Carolina, South Carolina, and Georgia. The scope of attacks by the "Chickamauga" and their allies ranged from quick raids by small war parties of a handfull of warriors to large campaigns by four or five hundred, and once over a thousand, warriors. The Upper Muskogee under Dragging's Canoe's close ally Alexander McGillivray frequently joined their campaigns as well as operating separately, and the settlements on the Cumberland came under attack from the Chickasaw, Shawnee from the north, and Delaware as well. Campaigns by Dragging Canoe and his successor, John Watts, were frequently conducted in conjunction campaigns in the Northwest. The response by the colonists were usually attacks in which Cherokee towns in peaceful areas were completely destroyed, though usually without great loss of life on either side. The wars continued until the Treaty of Tellico Blockhouse in November 1794.

Northwest Indian War

In 1787, the Northwest Ordinance officially organized the Northwest Territory for white settlement. American settlers began pouring into the region. Violence erupted as Indians resisted this encroachment, and so the administration of President George Washington sent armed expeditions into the area to put down native resistance. However, in the Northwest Indian War, a pan-tribal confederacy led by Blue Jacket (Shawnee), Little Turtle (Miami), Buckongahelas (Lenape), and Egushawa (Ottawa) crushed armies led by Generals Josiah Harmar and Arthur St. Clair. General St. Clair's defeat was the severest loss ever inflicted upon an American army by Native Americans. The Americans attempted to negotiate a settlement, but Blue Jacket and the Shawnee-led confederacy insisted on a boundary line the Americans found unacceptable, and so a new expedition led by General Anthony Wayne was dispatched. Wayne's army defeated the Indian confederacy at the Battle of Fallen Timbers in 1794. The Indians had hoped for British assistance; when that was not forthcoming, the Indians were compelled to sign the Treaty of Greenville in 1795, which ceded modern-day Ohio and part of Indiana to the United States.

Tecumseh, the Creek War, and the War of 1812

The United States continued to gain title to Native American land after the Treaty of Greenville, at a rate that created alarm in Indian communities. In 1800, William Henry Harrison became governor of the Indiana Territory and, under the direction of President Thomas Jefferson, pursued an aggressive policy of obtaining titles to Indian lands. Two Shawnee brothers, Tecumseh and Tenskwatawa, organized another pan-tribal resistance to American expansion. Tecumseh was concerned at the rapid deterioration of Native American communities with the encroachment of whites in the area. His goal was to get Native American leaders to stop selling land to the United States.[5]

While Tecumseh was in the south attempting to recruit allies among the Creeks, Cherokees, and Choctaws, Harrison marched against the Indian confederacy, defeating Tenskwatawa and his followers at the Battle of Tippecanoe in 1811.[6] The Americans hoped that the victory would end the militant resistance, but Tecumseh instead chose to openly ally with the British, who were soon at war with the Americans in the War of 1812.[7]

Like the Revolutionary War, the War of 1812 was also a massive Indian war on the western front. Encouraged by Tecumseh, the Creek War (1813-1814), which began as a civil war within the Creek (Muscogee) nation, became part of the larger struggle against American expansion. Although the war with the British was a stalemate, the United States was more successful on the western front. Tecumseh was killed by Harrison's army at the Battle of the Thames, ending the resistance in the Old Northwest. The Creeks who fought against the United States were defeated. The First Seminole War, in 1818, was in some ways a continuation of the Creek War and resulted in the transfer of Florida to the United States in 1819.[8]

As in the Revolution and the Northwest Indian War, after the War of 1812, the British abandoned their Indian allies to the Americans. This proved to be a major turning point in the Indian Wars, marking the last time that Native Americans would turn to a foreign power for assistance against the United States.

Removal era wars

One of the results of these wars was passage of the Indian Removal Act in 1830, which President Andrew Jackson signed into law in 1830. The Removal Act did not order the removal of any American Indians, but it authorized the President to negotiate treaties that would exchange tribal land in the east for western lands that had been acquired in the Louisiana Purchase. According to historian Robert V. Remini, Jackson promoted this policy primarily for reasons of national security, seeing that Great Britain and Spain had recruited and armed Native Americans within U.S. borders in wars with the United States.[9]

Numerous Indian Removal treaties were signed. Most American Indians reluctantly but peacefully complied with the terms of the removal treaties, often with bitter resignation. Some groups, however, went to war to resist the implementation of these treaties. This resulted in two short wars (the Black Hawk War of 1832 and the Creek War of 1836), as well as the long and costly Second Seminole War (1835–1842).

West of the Mississippi (1823–1890)

As in the East, expansion into the plains and mountains by miners, ranchers and settlers led to increasing conflicts with the indigenous population of the West. Many tribes — from the Utes of the Great Basin to the Nez Perces of Idaho — fought the whites at one time or another. But the Sioux of the Northern Plains and the Apache of the Southwest provided the most significant opposition to encroachment on tribal lands. Led by resolute, militant leaders, such as Red Cloud and Crazy Horse, the Sioux were skilled at high-speed mounted warfare. The Sioux were new arrivals on the Plains—previously they had been sedentary farmers in the Great Lakes region. Once they learned to capture and ride horses, they moved west, destroyed other Indian tribes in their way, and became feared warriors. Historically the Apaches bands supplimented their economy by raiding others and practiced warfare to avenge a death of a kinsman. The Apache bands were equally adept at fighting and highly elusive in the environs of desert and canyons.

Plains

White conflict with the Plains Indians continued through the Civil War. The Dakota War of 1862 (more commonly called the Sioux Uprising of 1862 in older authorities and popular texts) was the first major armed engagement between the U.S. and the Sioux. After six weeks of fighting in Minnesota, led mostly by Chief Taoyateduta (aka, Little Crow), records conclusively show that more than 500 U.S. soldiers and settlers died in the conflict, though many more may are believed to have died in small raids or after being captured. The number of Sioux dead in the uprising is mostly undocumented, but after the war, 303 Sioux were convicted of murder and rape by U.S. military tribunals and sentenced to death. Most of the death sentences were commuted, but on December 26, 1862, in Mankato, Minnesota, 38 Dakota Sioux men were hanged in what is still today the largest mass execution in U.S. history. "Most of the thirty-nine were baptized, including Tatemima (or Round Wind), who was reprieved at the last minute."[10]

In 1864, one of the more infamous Indian War battles took place, the Sand Creek Massacre. A locally raised militia attacked a village of Cheyenne and Arapaho Indians in southeast Colorado and killed and mutilated an estimated 150 men, women, and children. The Indians at Sand Creek had been assured by the U.S. Government that they would be safe in the territory they were occupying, but anti-Indian sentiments by white settlers were running high. Later congressional investigations resulted in short-lived U.S. public outcry against the slaughter of the Native Americans.[11]

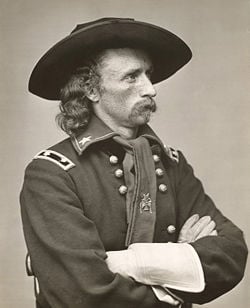

In 1875, the last serious Sioux war erupted, when the Dakota gold rush penetrated the Black Hills. The U.S. Army did not keep miners off Sioux (Lakota) hunting grounds; yet, when ordered to take action against bands of Sioux hunting on the range, according to their treaty rights, the Army moved vigorously. In 1876, after several indecisive encounters, General George Custer found the main encampment of the Lakota and their allies at the Battle of Little Big Horn. Custer and his men — who were separated from their main body of troops — were all killed by the far more numerous Indians who had the tactical advantage. They were led in the field by Crazy Horse and inspired by Sitting Bull's earlier vision of victory.

Later, in 1890, a Ghost Dance ritual on the Northern Lakota reservation at Wounded Knee, South Dakota, led to the Army's attempt to subdue the Lakota. During this attempt, gunfire erupted, and soldiers murdered approximately 100 Indians. The approximately 25 soldiers who died may have been killed by friendly fire during the battle. Long before this, the means of subsistence and the societies of the indigenous population of the Great Plains had been destroyed by the slaughter of the buffalo, driven almost to extinction in the 1880s by indiscriminate hunting.

Southwest

The conflicts in this large geographical area span from 1846 to 1895. They involved every non-pueblo tribe in this region and often were a continuation of Mexican-Spanish conflicts. The Navajo and Apaches conflicts are perhaps the best known, but they were not the only ones. The last major campaign of the U.S. military in the Southwest involved 5,000 troops in the field. This caused the Apache Geronimo and his band of 24 warriors, women and children to surrender in 1886.

The tribes or bands in the southwest (including the Pueblos), had been engaged in cycles of trading and fighting each other and foreign settlers for centuries prior to the United States annexing their region from Mexico in 1840.

Wars of the West timeline

- Comanche Wars (1836-1875) on the southern plains, primarily Texas Republic and the state

- Cayuse War (1848–1855) — Oregon Territory-Washington Territory

- Rogue River Wars (1855-1856) — Oregon Territory

- Yakima War (1855–1858) — Washington Territory

- Spokane-Coeur d'Alene-Paloos War (1858) — Washington Territory

- Fraser Canyon War (1858) – British Columbia (U.S. irregulars on British territory)

- California Indian Wars (1860-65) War against Hupa, Wiyot, Yurok, Tolowa, Nomlaki, Chimariko, Tsnungwe, Whilkut, Karuk, Wintun and others.

- Lamalcha War (1863) — British Columbia

- Chilcotin War (1864) — British Columbia

- Navajo Wars (1861–1864) — ended with Long Walk of the Navajo — Arizona Territory and New Mexico Territory.

- Hualapai or Walapais War (1864–1869) — Arizona Territory

- Apache Campaigns or Apache Wars (1864–1886) Careleton put Mescelero on reservation with Navajos at Sumner and continued until 1886, when Geronimo surrendered.

- Dakota War of 1862 — skirmishes in the southwestern quadrant of Minnesota result in hundreds dead. In the largest mass execution in U.S. history, 38 Dakota were hanged. About 1,600 others were sent to a reservation in present-day South Dakota.

- Red Cloud's War (1866–1868) — Lakota chief Makhpyia luta (Red Cloud) conducts the most successful attacks against the U.S. Army during the Indian Wars. By the Treaty of Fort Laramie (1868), the U.S. granted a large reservation to the Lakota, without military presence or oversight, no settlements, and no reserved road building rights. The reservation included the entire Black Hills.

- Colorado War (1864–1865) — clashes centered on the Colorado Eastern Plains between the U.S. Army and an alliance consisting largely of the Cheyenne and Arapaho.

- Sand Creek Massacre (1864) — John Chivington killed more than 450 surrendered Cheyenne and Arapaho.

- Comanche Campaign (1867–1875) — Maj. Gen. Philip Sheridan, in command of the Department of the Missouri, instituted winter campaigning in 1868–69 as a means of rooting out the elusive Indian tribes scattered throughout the border regions of Colorado, Kansas, New Mexico, and Texas.[12]

- See Fifth Military District {Texas} for reports of US Cavalry vs. Native Americans from August 1867 to September 1869. (US Cavalry units in Texas were the 4th Cavalry Regiment (United States); 6th Cavalry Regiment (United States) and the 9th Cavalry Regiment (United States)).

- Battle of Beecher Island (1868) — northern Cheyenne under war leader Roman Nose fought scouts of the U.S. 9th Cavalry Regiment in a nine-day battle.

- Battle of Washita River (1868) — George Armstrong Custer’s 7th U.S. Cavalry attacked Black Kettle’s Cheyenne village on the Washita River (near present day Cheyenne, Oklahoma). 250 men, women and children were killed.

- Battle of Summit Springs (1869) Cheyenne Dog Soldiers led by Tall Bull defeated by elements of U.S. Army under command of Colonel Eugene A. Carr. Tall Bull died, reportedly killed by Buffalo Bill Cody.

- Battle of Palo Duro Canyon (1874) — Cheyenne, Comanche, and Kiowa warriors engaged elements of the U.S. 4th Cavalry Regiment led by Colonel Ranald S. Mackenzie.

- Modoc War, or Modoc Campaign (1872–1873) — 53 Modoc warriors under Captain Jack held off 1,000 men of the U.S. Army for 7 months. Major General Edward Canby was killed during a peace conference—the only general to be killed during the Indian Wars.

- Red River War (1874–1875) — between Comanche and U.S. forces under the command of William Sherman and Lt. General Phillip Sheridan.

- Black Hills War, or Little Big Horn Campaign (1876–1877) — Lakota under Sitting Bull and Crazy Horse fought the U.S. after repeated violations of the Treaty of Fort Laramie (1868).

- Battle of the Rosebud (1876) — Lakota under Tasunka witko clashed with U.S. Army column moving to reinforce Custer's 7th Cavalry.

- Battle of the Little Bighorn (1876) — Sioux and Cheyenne under the leadership of Sitting Bull and Crazy Horse defeated the 7th Cavalry under George Armstrong Custer.

- Nez Perce Campaign or Nez Perce War (1877) — Nez Perce under Chief Joseph retreated from the 1st U.S. Cavalry through Idaho, Yellowstone Park, and Montana after a group of Nez Perce attacked and killed a group of Anglo settlers in early 1877.

- Bannock Campaign or Bannock War (1878 — elements of the 21st U.S. Infantry, 4th U.S. Artillery, and 1st U.S. Cavalry engaged the natives of southern Idaho including the Bannock and Paiute when the tribes threatened rebellion in 1878, dissatisfied with their land allotments.

- Cheyenne Campaign or Cheyenne War (1878–1879) — a conflict between the United States' armed forces and a small group of Cheyenne families.

- Sheepeater Campaign or Sheepeater War (May – August 1879) — on May 1, 1879, three detachments of soldiers pursued the Idaho Western Shoshone throughout central Idaho during the last campaign in the Pacific Northwest.

- Ute Campaign or Ute War (September 1879–November 1880) — on September 29, 1879, some 200 men, elements of the 4th U.S. Infantry and 5th U.S. Cavalry under the command of Maj. T. T. Thornburgh, were attacked and besieged in Red Canyon by 300 to 400 Ute warriors. Thornburgh's group was rescued by forces of the 5th and U.S. 9th Cavalry Regiment in early October, but not before significant loss of life had occurred. The Utes were finally pacified in November 1880.

- Pine Ridge Campaign (November 1890–January 1891) — numerous unresolved grievances led to the last major conflict with the Sioux. A lopsided engagement that involved almost half the infantry and cavalry of the Regular Army caused the surviving warriors to lay down their arms and retreat to their reservations in January 1891.

- Wounded Knee Massacre (December 29, 1890) — Sitting Bull's half-brother, Big Foot, and 152 other Sioux were killed, 25 U.S. cavalrymen also died in the engagement. 7th Cavalry (only fourteen days before, Sitting Bull had been killed with his son Crow Foot at Standing Rock Agency in a gun battle with a group of Indian police that had been sent by the American government to arrest him).

Last battles (1898 and 1917)

- October 5, 1898, Leech Lake, Minnesota Battle of Sugar Point. Last Medal of Honor given for Indian Wars Campaigns was awarded to Pvt. Oscar Burkard of 3rd U.S. Infantry Regiment

- 1917—U.S. 10th Cavalry Regiment involved in firefight with Yaqui Indians just west of Nogales, Arizona.

U.S. forces

Scouts

- Apache Scouts

- Navajo Scouts

- Seminole Black Scouts (who were scouts for the Buffalo Soldiers with the 10th Cavalry)

- U.S. Army Indian Scouts general

Cavalry

- U.S. 1st Cavalry Regiment – 1834; 1836 to 1892

- U.S. 2nd Cavalry Regiment – 1867 & 1870

- U.S. 3d Armored Cavalry Regiment – 1869

- U.S. 4th Cavalry Regiment – 1865 to 1886

- U.S. 5th Cavalry Regiment – 1876

- U.S. 6th Cavalry Regiment – 1867 to 1885 & 1890

- U.S. 7th Cavalry Regiment – 1871 to 1890

- U.S. 8th Cavalry Regiment – 1867-1869; 1877

- U.S. 9th Cavalry Regiment – 1868; 1875-1881 (Buffalo Soldiers)

- U.S. 10th Cavalry Regiment- 1867-1868; 1875; 1879-1880; 1885; 1917 (Buffalo Soldiers)

- U.S. 113th Cavalry Regiment

Infantry

- U.S. 1st Infantry Regiment – 1791; 1832; 1839-1842; 1870s-1890s.

- U.S. 2d Infantry Regiment[13]

- 3rd U.S. Infantry Regiment – 1792; 1856-1858; 1860; 1887; 1898

- U.S. 4th Infantry Regiment – 1808; 1816-1836; 1869-1879

- U.S. 5th Infantry Regiment – 1877[14]

- U.S. 6th Infantry Regiment – 1823-1879

- U.S. 9th Infantry Regiment – 1876

- U.S. 10th Infantry Regiment – 1874

- U.S. 11th Infantry Regiment

- U.S. 12th Infantry Regiment – 1872-1873; 1878; 1890-1891

- U.S. 13th Infantry Regiment – 1867-1871

- U.S. 14th Infantry Regiment – 1876

- U.S.15th Infantry Regiment

- U.S. 16th Infantry Regiment[15]

- U.S. 18th Infantry Regiment – 1866-1890

- U.S. 21st Infantry Regiment[16]

- U.S. 22d Infantry Regiment – 1869; 1872; 1876-1877

- U.S. 23rd Infantry Regiment – 1866, 1868, 1876

- U.S. 24th Infantry Regiment (Buffalo Soldiers) 1866-1890s

- U.S. 25th Infantry Regiment (Buffalo Soldiers) 1866-1890s

See also

- Mississippi Rifles {155th Infantry Regiment MNG}; War of 1812 Fort Mims

Artillery

- Company F, U.S. 5th Artillery Regiment[18]

Historiography

In American history books, the Indian Wars have often been treated as a relatively minor part of the military history of the United States. Only in last few decades of the twentieth century did a significant number of historians begin to include the American Indian point of view in their writings about those wars, emphasizing the impact of the wars on native peoples and their cultures.

A well-known and influential book in popular history was Dee Brown's Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee (1970). In academic history, Francis Jennings's The Invasion of America: Indians, Colonialism, and the Cant of Conquest (New York: Norton, 1975) was notable for its reversal of the traditional portrayal of Indian-European relations. A recent and important release from the perspective of both Indians and the soldiers is Jerome A. Greene's INDIAN WAR VETERANS: Memories of Army Life and Campaigns in the West, 1864-1898 (New York, 2007).

In his book The Wild Frontier: Atrocities during the American-Indian War from Jamestown Colony to Wounded Knee, amateur historian William M. Osborn sought to tally every recorded atrocity in the geographical territory that would eventually become the continental United States, from first contact (1511) to the closing of the frontier (1890). He determined that 9,156 people died from atrocities perpetrated by Native Americans, and 7,193 people died from those perpetrated by Europeans. Osborn defines an atrocity as the murder, torture, or mutilation of civilians, the wounded, and prisoners.[19]

Some historians now emphasize that to see the Indian wars as a racial war between Indians and White Americans simplifies the complex historical reality of the struggle. Indians and whites often fought alongside each other; Indians often fought against Indians, as they had done for centuries before the arrival of any Europeans. In one example, although the Battle of Horseshoe Bend is often described as an "American victory" over the Creek Indians, the victors were a combined force of Cherokees, Creeks, and Tennessee militia led by Andrew Jackson. From a broad perspective, the Indian wars were about the conquest of Native American peoples by the United States; up close it was rarely as simple as that.

Notes

- ↑ Gregory F. Michno, Encyclopedia of Indian Wars: Western Battles and Skirmishes 1850-1890 (Missoula, MT: Mountain Press Publishing Company, 2003), Index.

- ↑ Russell Thornton. American Indian Holocaust and Survival: A Population History Since 1492. (Oklahoma City: University of Oklahoma Press, 1987), 48–49.

- ↑ Ray Raphael. A People's History of the American Revolution: How Common People Shaped the Fight for Independence. (New York: The New Press, 2001), 244.

- ↑ Robert M. Utley and Wilcomb E. Washburn. Indian Wars. (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, [1977] 1987), 112.

- ↑ Utley and Washburn, 117-118.

- ↑ Utley and Washburn, 118-121.

- ↑ Utley and Washburn, 123.

- ↑ Utley and Washburn, 131-134.

- ↑ Robert V. Remini. Andrew Jackson and his Indian Wars. (New York: Viking, 2001), 113.

- ↑ Kenneth Carley. The Sioux Uprising of 1862 (St. Paul: Minnesota Historical Society, 1961), 65.

- ↑ Utley and Washburn, 228.

- ↑ United States Army Center for Military History, Named Campaigns — Indian Wars, Named Campaigns - Indian Wars Retrieved December 13, 2005.

- ↑ The Institute of Heraldry, 2d Infantry Regiment, 2d Infantry Regiment Retrieved November 1, 2007.

- ↑ The Institute of Heraldry, 5th Infantry, 5th Infantry Retrieved November 1, 2007.

- ↑ The Institute of Heraldry, 16th Infantry Regiment, 16th Infantry Regiment Retrieved November 1, 2007.

- ↑ The Institute of Heraldry, 21st Infantry Regiment, 21st Infantry Regiment Retrieved November 1, 2007.

- ↑ 4th Battalion (Mechanized) / 23rd Infantry Regiment "Tomahawks" Association, Lineage And Honors Information 4th Battalion / 23rd Infantry Lineage as of: 10 May 2007, Lineage Retrieved November 1, 2007.

- ↑ The Institute of Heraldry, 5th Artillery Regiment, 5th Artillery Regiment Retrieved November 1, 2007.

- ↑ William M. Osborn, The Wild Frontier: Atrocities During The American-Indian War (New York: Random House, 2000),Review of The Wild Frontier: Atrocities During The American-Indian War onlinewww.natvanbooks.com. Retrieved November 1, 2007.

References

ISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- 4th Battalion (Mechanized) / 23rd Infantry Regiment "Tomahawks" Association. Lineage And Honors Information 4th Battalion / 23rd Infantry Lineage as of: 10 May 2007. Lineage Retrieved November 1, 2007.

- Carley, Kenneth. The Sioux Uprising of 1862. St. Paul: Minnesota Historical Society, 1961.

- The Institute of Heraldry. 2d Infantry Regiment. 2d Infantry Regiment Retrieved November 1, 2007.

- The Institute of Heraldry. 5th Artillery Regiment. 5th Artillery Regiment Retrieved November 1, 2007.

- The Institute of Heraldry. 5th Infantry. 5th Infantry Retrieved November 1, 2007.

- The Institute of Heraldry. 16th Infantry Regiment. 16th Infantry Regiment Retrieved November 1, 2007.

- The Institute of Heraldry. 21st Infantry Regiment. 21st Infantry Regiment Retrieved November 1, 2007.

- Michno, Gregory F. Encyclopedia of Indian Wars: Western Battles and Skirmishes 1850-1890. Missoula, MT: Mountain Press Publishing Company, 2003. ISBN 0878424687

- Osborn, William M. The Wild Frontier: Atrocities During The American-Indian War. New York: Random House, 2000. Review of The Wild Frontier: Atrocities During The American-Indian War online Retrieved November 1, 2007.

- Parker, Aaron. The Sheepeater Indian Campaign. Chamberlin Basin Country: Idaho Country Free Press, 1968.

- Raphael, Ray. A People's History of the American Revolution: How Common People Shaped the Fight for Independence. New York: The New Press, 2001. ISBN 0-06-000440-1

- Remini, Robert V. Andrew Jackson and his Indian Wars. New York: Viking, 2001. ISBN 0-670-91025-2

- Richter, Daniel K. Facing East from Indian Country: A Native History of Early America. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2001. ISBN 0-674-00638-0

- Thornton, Russell. American Indian Holocaust and Survival: A Population History Since 1492. Oklahoma City: University of Oklahoma Press, 1987. ISBN 0-8061-2220-X

- United States Army Center for Military History. Named Campaigns — Indian Wars. Named Campaigns - Indian Wars Retrieved December 13, 2005.

- Utley, Robert M., and Wilcomb E. Washburn. Indian Wars. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, [1977] 1987. ISBN 0-8281-0202-3

- Yenne, Bill. Indian Wars: The Campaign for the American West. Yardley, PA: Westholme, 2005. ISBN 1-59416-016-3

Further reading

- Greene, Jerome A. Indian War Veterans: Memories of Army Life and Campaigns in the West, 1864-1898. El Dorado Hills, CA: Savas Beatie, 2007.

- Kip, Lawrence. Army life on the Pacific : a journal of the expedition against the northern Indians, the tribes of the Cour d'Alenes, Spokans, and Pelouzes, in the summer of 1858. New York: Redfield, 1859. Washington State Library's Classics in Washington History collection - Army life on the Pacific Retrieved November 1, 2007.

- McDermott, John D. A Guide to the Indian Wars of the West. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1998. ISBN 0-8032-8246-X

External links

All links retrieved March 1, 2018.

- Indian Wars and Pioneers of Texas by John Henry Brown, published 1880, hosted by the Portal to Texas History.

- Increase Mather, A Brief History of the War with the Indians in New-England (1676) Online Edition

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.

↧ Download as ZWI file | Last modified: 02/04/2023 00:44:22 | 84 views

☰ Source: https://www.newworldencyclopedia.org/entry/Indian_Wars | License: CC BY-SA 3.0

ZWI signed:

ZWI signed:

KSF

KSF