Aristophanes

From Nwe

From Nwe Aristophanes (Greek: Ἀριστοφάνης) (c. 446 B.C.E. – c. 388 B.C.E.) was a Greek dramatist of the Old and Middle Comedy period. He is also known as the "Father of Comedy" and the "Prince of Ancient Comedy." The Old Comedy, dating from the establishment of democracy by Kleisthenes, around 510 B.C.E., arose from the obscene jests of Dionysian revelers, composed of virulent abuse and personal vilification. The satire and abuse were directed against some object of popular dislike. The comedy used the techniques of tragedy, its choral dances, its masked actors, its meters, its scenery and stage mechanism, and above all the elegance of the Attic language, but used for the purpose of satire and ridicule. Middle Comedy omitted the chorus, and transferred the ridicule from a single personage to human foibles in general. Aristophanes was one of the key figures of this transition.

Biography

The place and exact date of his birth are unknown, but he was around thirty in the 420s B.C.E. when he achieved sudden brilliant success in the Theater of Dionysus with his Banqueters. He lived in the deme of Kudathenaion (the same as that of the leading Athenian statesman Cleon) which implies he was from a relatively wealthy family and, accordingly, well educated. He is famous for writing comedies such as The Birds for the two Athenian dramatic festivals: The City Dionysia and the Lenea. He wrote forty plays, eleven of which survive; his plays are the only surviving complete examples of Old Attic Comedy, although extensive fragments of the work of his rough contemporaries, Cratinus and Eupolis, survive. Many of Aristophanes' plays were political, and often satirized well-known citizens of Athens and their conduct in the Peloponnesian War and after. Hints in the text of his plays, supported by ancient scholars, suggest that he was prosecuted several times by Cleon for defaming Athens in the presence of foreigners; although there is no corroborating evidence outside his plays. The Frogs was given the unprecedented honor of a second performance. According to a later biographer, he was also awarded a civic crown for the play.

Aristophanes was probably victorious at least once at the City Dionysia, with Babylonians in 426 (IG II2 2325. 58), and at least three times at the Lenaia, with Acharnians in 425, The Knights in 424, and The Frogs in 405. His sons Araros, Philippus, and Nicostratus were also comic poets. Araros is said to have been heavily involved in the production of Wealth II in 388 (test. 1. 54–6) and to have been responsible for the posthumous performances of Aeolosicon II and Cocalus (Cocalus test. iii), with which he seems to have taken the prize at the City Dionysia in 387 (IG II2 2318. 196). Philippus was twice victorious at the Lenaia (IG II2 2325. 140) and apparently produced some of Eubulus’ comedies (Eub. test. 4). (Aristophanes’ third son is sometimes said to have been called not Nicostratus but Philetaerus, and a man by that name appears in the catalogue of Lenaia victors with two victories, the first probably in the late 370s, at IG II2 2325. 143).

Aristophanes appears as a character in Plato's Symposium, in which he offers a humorous mythical account of the origin of Love. Plato's text was produced a generation after the events it portrays and is a patently apologetic attempt to show that Socrates and Aristophanes were not enemies, despite the attack on the philosopher in The Clouds (original production 423 B.C.E.). The Symposium is therefore best treated as an early chapter in the history of the reception of Aristophanes and his poetry rather than as a description of anything approaching a historical event.

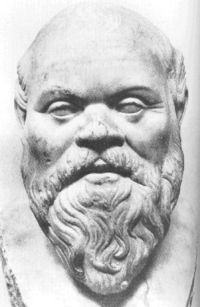

Of the surviving plays, The Clouds was a disastrous production resulting in a humiliating and long-remembered third place (cf. the parabasis of the revised (preserved) version of the play, and the parabasis of the following year's The Wasps). The play, which satirizes the sophistic learning en vogue among the aristocracy at the time, placed poorly at the City Dionysia. Socrates was the principal target and emerges as a typical Sophist; in Plato's Apology at 18d, the character of Socrates suggests that it was the foundation of those charges which led to Socrates' conviction. Lysistrata was written during the Peloponnesian War between Athens and Sparta and argues not so much for pacifism as for the idea that the states ought not be fighting one another at this point but combining to rule Greece. In the play, this is accomplished when the women of the two states show off their bodies and deprive their husbands of sex until they stop fighting. Lysistrata was later illustrated at length by Pablo Picasso.

The Clouds

| The Clouds | |

|---|---|

|

|

| Written by | Aristophanes |

| Chorus | clouds |

| Characters | Strepsiades Phidippides servant of Strepsiades disciples of Socrates Socrates Just Discourse Unjust Discourse Pasias Amynias |

| Mute | {{{mute}}} |

| Setting | before the houses of Strepsiades and Socrates |

The Clouds (Νεφέλαι) is a comedy which lampoons the sophists and the intellectual trends of late fifth century Athens. Although it took last place in the comic festival Aristophanes entered it in, it is one of his most famous works because it offers a highly unusual portrayal of Socrates. Many also find the play to be quite funny as an irreverent satire of pretentious academia.

Aristophanes re-wrote the play after its initial failure, inserting an interlude into the middle of the action in which the playwright himself takes the stage and chastises the audience for their poor sense of humor. Thus the play can also be regarded as a precursor to self-referential or post-modern literature.

The plot

The play opens with a citizen of Athens, Strepsiades (whose name means "Twister"), bemoaning the addiction of Pheidippides, his pretty-boy son, to horse-racing, and buying of expensive items and horses which has put him into deep debt. He recalls his own humble upbringing on a farm and curses his marriage to an aristocratic city woman, whose wealth he believes is responsible for spoiling his son. Pheidippides refuses to get a job. Socrates emerges in the play, explaining his descent from the heavens, and enters into dialog with Strepsiades.

Socrates requires Strepsiades to strip naked in order to take him into the Thinkery (Phrontisterion). Aristophanes himself then appears on stage and explains his play with verse of some eloquence. The Thinkery is populated by starving students and pedantic scoundrels, foremost is Socrates' associate Chaerephon. After demonstrating a few of his patently absurd "discoveries" (for instance, the leg span of a flea, or the reason why flies fart) the great philosopher explains to him that the god "Vortex" has replaced Zeus:

- "Strepsiades: But is it not He who compels this to be? does not Zeaus this Necessity send?

- Socrates: No Zeus have we there, but a Vortex of air.

- Strepsiades: What! Vortex? that's something, I own. I knew not before, that Zeus was no more, but Vortex was placed on his throne!"

Upon learning this, Strepsiades tells his son what he has learned and encourages him to study under Socrates as well. Pheidippides arrives at the Thinkery, and two figures stage a debate (apparently modelled on a cock fight) designed to demonstrate the superiority of the new versus the old style of learning. One goes by the name Kreittôn (Right, Correct, Stronger), and the other goes by the name Êttôn (wrong, incorrect, weaker). These names are a direct reference to Protagoras's statement that a good rhetorician was able to make the weaker argument seem the stronger; a statement seen as one of the key beliefs of the sophists. As the debate gets set up, the audience learns that there are two types of logic taught at the Thinkery. One is the traditional, philosophical education, and the other is the new, sophistic, rhetorical education. Right Logic explains that Pheidippides ought to study the traditional way as it is more moral and manly. Wrong Logic refutes him, using some very twisty logic that winds up (in true Greek comedic fashion), insulting the entire audience in attendance.

Pheidippides agrees to study the new logic at the Thinkery. Shortly afterward, Strepsiades learns that the Clouds actually exist to teach mortals a lesson in humility. They have in fact been masquerading as goddesses of philosophy to reveal the airy and pretentious nature of academic learning and sophistic rhetoric: "We are," proclaims their leader,

-

- Shining tempters formed of air, symbols of desire;

- And so we act, beckoning, alluring foolish men

- Through their dishonest dreams of gain to overwhelming

- Ruin. There, schooled by suffering, they learn at last

- To fear the gods.

Dejected, Strepsiades goes to speak to his son and asks him what he has learned. Pheidippides has found a loophole that will let them escape from their debts, but in the process he has imbibed new and revolutionary ideas that cause him to lose all respect for his father. The boy calmly proceeds to demonstrate the philosophical principles that show how it is morally acceptable for a son to beat his father. Strepsiades takes this in stride, but when Phedippides also begins to speak of beating his mother, the old man finally becomes fed up with the new-fangled learning of Socrates and, after consulting with a statue of Apollo, he seizes a torch, climbs on to the rafters of the Phrontisterion, and sets it on fire. The play's final scene depicts a vicious beating and thrashing of Socrates, and his bedraggled students, while they comically choke on smoke and ash.

Despite its brilliance as a work of comic drama, which is almost universally agreed upon, The Clouds has acquired an ambivalent reputation. Some believe it was responsible for stirring up civic dissension against Socrates that may have contributed to his execution. The play's portrayal of Socrates as a greedy sophist runs contrary to every other account of his career: While he did teach philosophy and rhetoric to his students, he never took money for his teaching, and he frequently derided the sophists for their disingenuous arguments and lack of moral scruple. What Aristophanes intended by confounding Socrates with the sophists is perhaps impossible to determine. However, the references to the play that Socrates made during his trial suggest that he was not greatly offended by The Clouds (he is reported to have obligingly stood for the audience and waved at close of the play's first performance). Furthermore, Plato's Symposium, written after Clouds but possibly a purely fictional narrative, shows Aristophanes and Socrates quite amiably drinking together and speaking as friends.

Interpretation

The Clouds, straddling the lines drawn by Aristotle between comedy and drama in the Poetics, is actually a metaphor for the folly of humankind before the majesty of the Cosmos; all characters, including Socrates, have pride and vanities; all are flawed, and the lampoon is against human weakness itself, which provides the comic aspect of the play. The Clouds exist beyond the world of men in the play, and are the "truth" Aristophanes is brilliantly expounding the Oven, fueled by the Clouds, is the "test" that humankind must pass through (for in the play all of society is being tested, and fails); the Clouds are the catalyst of the test.

Incidentally, there are several references in the play to esoteric knowledges (Strepsiades, in destroying the Academy, goes on to mock Socrates for "looking to the moon," which had been referenced earlier as one of the characters complained about Athens' calendar being inaccurate in regards to the New Moon); Aristophanes would have been aware of these things, and was likely mocking the hypocrisy of the various circles of Athens, especially those who claimed to be "initiated" into deeper mysteries, which Aristophanes is demonstrating to be mere folly in comparison to the reality of these mysteries, namely, the Clouds and the Universe itself.

Thus, the play can be seen as being a Cave of caves, an allegory comparable to the Cave in Plato's Republic, but transcending it.

Translations

- William James Hickie, 1905—prose

- Benjamin B. Rogers, 1924—verse

- Arthur S. Way, 1934—verse

- Robert Henning Webb, 1960—verse

- William Arrowsmith, 1962—prose and verse

- Thomas G. West & Grace Starry West, 1984—prose

- Peter Meineck, 1998—prose

- Ian Johnston, 2003—verse

Surviving plays

- The Acharnians (425 B.C.E.): The standard edition is by S. Douglas Olson (Oxford University Press)

- The Knights (424 B.C.E.): There is no good complete modern scholarly edition of the play, although Jeffrey Henderson has been engaged for a number of years in producing one

- The Clouds (original 423 B.C.E., uncompleted revised version from 419 B.C.E.–416 B.C.E. survives): The standard edition is by K. J. Dover (Oxford University Press)

- The Wasps (422 B.C.E.): The standard edition is by D. MacDowell (Oxford University Press)

- Peace (first version, 421 B.C.E.): The standard edition is by S. Douglas Olson (Oxford University Press)

- The Birds (414 B.C.E.): The standard edition is by Nan Dunbar (Oxford University Press)

- Lysistrata (411 B.C.E.): The standard edition is by Jeffrey Henderson (Oxford University Press)

- Thesmophoriazusae (The Women Celebrating the Thesmophoria, first version, c. 411 B.C.E.): The standard edition is by Colin Austin and S. Douglas Olson (Oxford University Press)

- The Frogs (405 B.C.E.): The standard edition is by K. J. Dover (Oxford University Press)

- Ecclesiazousae (The Assemblywomen, c. 392 B.C.E.): The standard edition is by R. G. Ussher (Oxford University Press)

- Plutus (Wealth, second version, 388 B.C.E.): The best modern scholarly edition is by A. H. Sommerstein (Aris and Philips)

Non-surviving plays

The standard modern edition of the fragments is Kassel-Austin, Poetae Comici Graeci III.2; Kock-numbers are now outdated and should not be used.

- Banqueters (427 B.C.E.)

- Babylonians (426 B.C.E.)

- Farmers (424 B.C.E.)

- Merchant Ships (423 B.C.E.)

- The Clouds (first version) (423 B.C.E.)

- Proagon (422 B.C.E.)

- Amphiaraos (414 B.C.E.)

- Plutus (Wealth, first version, 408 B.C.E.)

- Gerytades (uncertain, probably 407 B.C.E.)

- Koskalos (387 B.C.E.)

- Aiolosikon (second version, 386 B.C.E.)

Undated non-surviving plays

- Aiolosikon (first version)

- Anagyros

- Broilers

- Daidalos

- Danaids

- Dionysos Shipwrecked

- Centaur

- Niobos

- Heroes

- Islands

- Lemnian Women

- Old Age

- Peace (second version)

- Phoenician Women

- Poetry

- Polyidos

- Seasons

- Storks

- Telemessians

- Triphales

- Thesmophoriazusae (The Festival Women, second version)

- Women Encamping

References

ISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Bloom, Harold, ed., Aristophanes. Chelsea House, 2002. ISBN 0791063585

- Platter, Charles. Aristophanes and the Carnival of Genres (Arethusa Books). Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 2006. ISBN 0-8018-8527-2

- Revermann, Martin. Comic Business: Theatricality, Dramatic Technique, and Performance Contexts of Aristophanic Comedy. Oxford University Press, 2006. ISBN 9780198152712

External links

All links retrieved November 5, 2021.

- Aristophanes Greek texts.

- Works by Aristophanes. Project Gutenberg

- List of films based on Aristophanes plays

- The Clouds translated by William James Hickie, available for free via Project Gutenberg

- The Clouds: A Study Guide

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.

↧ Download as ZWI file | Last modified: 02/04/2023 01:57:49 | 34 views

☰ Source: https://www.newworldencyclopedia.org/entry/Aristophanes | License: CC BY-SA 3.0

ZWI signed:

ZWI signed:

KSF

KSF