Printing

From Nwe

From Nwe - For other articles that otherwise might have the same name, see Print (disambiguation).

Printing is a process for producing texts and images, typically with ink on paper, usually using a printing press or other kind of printing apparatus. It is often carried out as a large-scale, industrial process and is an essential part of paper-based (as opposed to present-day electronic or online) publishing and transaction printing.

In photography, the process of making a picture on photosensitive or other paper in either black and white or color, using a negative or positive as the image source, or nowadays a digital photograph image source and a printer that uses that digital file to make its image, is also known as printing.

History

Development of printing in China and Korea

Printing was first conceived of and developed in China. Primitive woodblock printing was in use there by the sixth century. In the Tang Dynasty, a Chinese writer named Fen Zhi first mentioned in his book "Yuan Xian San Ji" that the woodblock was used to print Buddhist scripture during the Zhenguan years (627~649 C.E.). The text was first written on a piece of thin paper, then glued face down onto a wooden plate. The characters were carved out to make a reverse-image wood-block printing plate that was used to print the text. These may have been short scripture pieces designed to be worn or carried as charms. Later long scrolls and books were produced, first by wood-block printing and then later on by using movable type. Inexpensive printed books became widely available in China during the Song Dynasty (960-1279).

The oldest known Chinese surviving printed work is a woodblock-printed Buddhist scripture of Wu Zetian period (684~705 C.E.); discovered in Tubofan, Xinjiang province, China in 1906, it is now stored in a calligraphy museum in Tokyo, Japan.

According to one account, the earliest printed book found so far was a Buddhist scripture, printed in 868, hidden at Dunhuang cave, along the Silk Road.

Block printing was a costly and time-consuming process because each carved block could be used only for a specific page of a particular book. The technique was known in Europe at a later date, where it was mostly used to print Bibles. Difficulties inherent in carving massive quantities of minute text for every block, combined with low levels of illiteracy at the time, "Pauper's Bibles" were printed that emphasized illustrations and used words sparsely. Each page required the carving of a new block, a time-consuming task; thus limiting the variety of books printed, due to cost. Woodblock printing had long been used to imprint images and designs on cloth.

The introduction of movable type changed the nature of printing. The movable type process was first invented by Bi Sheng in 1041 during Song Dynasty of China. Each piece of movable type had on it one Chinese character carved in relief on a small block of moistened clay. After the block had been hardened by fire, the type became hard and durable and could be used wherever required. The pieces of movable type could be glued to an iron plate and easily detached from the plate. Each piece of character could be assembled to print a page and then broken up and redistributed as needed.

Since there are thousands of Chinese characters, the benefit of the technique was not as large as with alphabetic based languages typically comprised of fewer than 50 characters. Still, movable type spurred scholarly pursuits in Song China and facilitated more creative modes of printing. Nevertheless, movable type was not extensively used in China until the European-style printing press was introduced in relatively recent times.

Using the woodblock press technique, an expert can print 2,000 or more sheets a day. In the ninth century, printed books first appeared in quantities in Shu (modern Szechuan province) and could be purchased from private dealers. Soon the printing technique spread to other provinces, and by the end of the ninth century it was common all over China. These printed books included Confucian classics, Buddhist scriptures, dictionaries, mathematics texts and others. By the year 1000, paged books in the modern style had replaced scrolls. By the twelfth and thirteenth century many Chinese libraries contained tens of thousands of printed books. Two-color black and red printing was seen as early as 1340.

Throughout the centuries, both movable type and block printing existed side by side in China. It is uncertain when printing was introduced to the Xinjiang area; however printing material in several languages was found in Turfan, dated as early as the thirteenth century. The Muslims knew about the technology but didn't use it. When Marco Polo visited China in the thirteenth century, he must have seen printed books. It is possible that he or some other Silk Road travellers brought that knowledge to Europe, which later inspired John Gutenberg to invent printing in the West.

Printing is considered one of the Four Great Inventions of ancient China.

The oldest known Korean surviving printed document is a Buddhist scripture, which dates to 751. [1] The oldest surviving book printed using the more sophisticated block printing, the Chinese Diamond Sutra (a Buddhist scripture), dates from 868.

A throne memorial in 1023 of the Northern Song Dynasty of China recorded that the central government at that time used copperplate to print paper money. It also used the movable copper-block to print the numbers and characters on the money; nowadays we can find these shadows from the Song Dynasty paper money. Later in the Jin Dynasty, people used a more developed version of the same technique to print paper money and formal official documents; the typical example of this kind of movable copper-block printing is a printed "check" of Jin Dynasty in the year of 1215.

The world's first movable type metal printing press was invented in Korea in 1234 by Chwe Yun-ui during the Goryeo Dynasty. The oldest extant movable metal-type book is the Jikji, printed in 1377 in Korea. Examples of this metal type are on display in the Asian Reading Room of the Library of Congress in Washington, D.C.

There is little direct evidence, but it is highly probable that the Far East printing technology diffused into Europe through the trade routes from China which went through India and on through the Arabic world.

Gutenberg and European Printing

Johann Gutenberg, of the German city of Mainz, developed European movable type printing technology in 1440. Johann Fust and Peter Schöffer experimented with him in Mainz. Basing the design of his machine on a wine-press, Gutenberg developed the use of raised and movable type. He is also credited with the first use of oil-based ink, which was more durable than previously used water-based inks. He printed on both vellum and paper, the latter having been introduced in Europe somewhat earlier from China by way of the Arabs, who had a paper mill in operation in Baghdad as early as 794.

Before inventing the printing press in the 1440s, Gutenberg had worked as a goldsmith. The skills and knowledge of metals that he learned as a craftsman were crucial to the later invention of the press. Gutenberg made his type from an alloy of lead, tin, and antimony, which was critical for producing durable type that produced high-quality prints.

While there are several local claims for the invention of the printing press in other parts of Europe, including Laurens Janszoon Coster in the Netherlands and Panfilo Castaldi in Italy, Gutenberg is credited by most scholars with its initial invention.

Presses for olives and wine were known in Europe since Roman times, and Gutenberg was the first to convert the concept for printing uses. He was also the first to use types made out of lead, which proved to be more suitable for printing than the clay, wooden or bronze types used in East Asia. To create these lead types, Gutenberg used what some considered his most ingenious invention, a special matrix whereby the moulding of new movable types with an unprecedented precision at short notice became feasible. Within a year after this, Gutenberg also published the first colored prints.

The development of the printing press revolutionized communication and book production leading to the spread of knowledge. A printing press was built in Venice in 1469, and by 1500 the city had 417 printers. In 1470 Johann Heynlin set up a printing press in Paris. In 1476, a printing press was developed in England by William Caxton. The Italian Juan Pablos set up an imported press in Mexico City in 1539. Stephen Day was the first to build a printing press in North America, at Massachusetts Bay in 1628, and helped establish the Cambridge Press.

Early print shops at the time of Gutenberg were run by master printers. These printers owned shops, selected and edited manuscripts, determined the sizes of print runs, sold the works they produced, raised capital and organized distribution—we could accurately say that they functioned as publishers as well as printers.

- Early print shop "apprentices," usually between the ages of 15 and 20, worked for master printers. Apprentices were not required to be literate, and literacy rates at the time were very low, in comparison to today. Apprentices prepared ink, dampened sheets of paper, and assisted at the press. An apprentice who wished to learn to become a "compositor" had to learn Latin and spend time under the supervision of a journeyman.

- Early "journeyman printers," after completing their apprenticeships, were free to roam Europe with their tools of trade and print where they journeyed to. This facilitated the spread of printing to areas that were eager to adapt the new methodologies.

- Early "compositors" were those who set the type for printing.

- Early "pressmen" were the persons who ran the press; printing was labor intensive.

- Master print shops became the cultural centre for literati.

- The earliest-known image of a European, Gutenberg-style print shop is the Dance of Death (Danse Macabre) by Matthias Huss, at Lyon, 1499. This image depicts a compositor standing at a compositor's case being grabbed by a skeleton. The case is raised to facilitate his work. The image also shows a pressman being grabbed by a skeleton. To the right of the print shop a bookshop is shown.

- In Prints and Visual Communication, William Ivins offers the following concise history of a series of rapid innovations in image and type printing at the end of the eighteenth century:

- At the end of the eighteenth century there were several remarkable innovations in the graphic techniques and those that were utilized to make their materials. Thomas Bewick developed the method of using engraving tools on the end of the wood. Alois Senefelder discovered lithography. Blake made relief etchings. Early in the nineteenth century Charles Stanhope, 3rd Earl Stanhope, George E. Clymer, Friedrich Koenig, and others introduced new kinds of type presses, which for strength surpassed anything that had previously been known.

- By 2006 there were approximately 30,700 printing companies in the United States, accounting for $112 billion in revenue, according to the 2006 U.S. Industry & Market Outlook.Barnes Reports Print jobs that move through the Internet made up 12.5 percent of the total U.S. Printing market in 2005, according to research firm InfoTrend/CAP Ventures.

Financing printing

Court records from the city of Mainz document that Johannes Fust was, for some time, Gutenberg's financial backer.

By the sixteenth century jobs associated with printing were becoming increasingly specialized. Structures supporting publishers were more and more complex, leading to this division of labour. In Europe between 1500 and 1700 the role of the Master Printer was dying out and giving way to the bookseller – publisher. Printing during this period had a stronger commercial imperative than previously. Risks associated with the industry however were substantial, although dependent on the nature of the publication.

Bookseller publishers negotiated at trade fairs and at print shops. Jobbing work appeared in which printers did menial tasks in the beginning of their careers to support themselves.

In the years 1500 – 1700, publishers developed several new methods of funding projects.

1. Cooperative associations/publication syndicates—a number of individuals shared the risks associated with printing and shared in the profit. This was pioneered by the French.

2. Subscription publishing—pioneered by the English in the early seventeenth century. A prospectus for a publication was drawn up by a publisher to raise funding. The prospectus was given to potential buyers who signed up for a copy. If there were not enough subscriptions the publication did not go ahead. Lists of subscribers were included in the books as endorsements. If enough people subscribed a reprint might occur. Some authors used subscription publication to bypass the publisher entirely.

3. Installment publishing—books were issued in parts until a complete book had been issued. This was not necessarily done under a specific time-allotment. It was an effective method of spreading cost over a period of time. It also allowed earlier returns on investment to help cover production costs of subsequent installments.

The Mechanick Exercises, by Joseph Moxon, in London, 1683, was said to be the first publication done in installments.

Publishing trade organizations allowed publishers to organize business concerns collectively. Systems of self-regulation occurred in these arrangements. For example, if one publisher did something to irritate other publishers he would be controlled by peer pressure. These arrangements helped deal with labor unrest among journeymen, who faced difficult working conditions. Brotherhoods predated unions, without the formal regulations now associated with unions.

Impact of printing

Diffusion of printing in Europe

In Europe, books were copied mainly in monasteries, or (from the thirteenth century) in commercial scriptoria, where scribes wrote them out by hand. Books were therefore a scarce resource. While it might take someone a year or more to hand copy a Bible, with the Gutenberg press it was possible to create several hundred copies a year, with two or three people who could read (and proofread), and a few people to support the effort. Each sheet still had to be fed manually, which limited the reproduction speed; and the type had to be set manually for each new page, which limited the number of different pages created per day. Books produced in this period, between the first work of Johann Gutenberg and the year 1500, are collectively referred to as incunabula.

The rise of printed works was not immediately popular. Not only did the Roman Curia contemplate making printing presses an industry requiring a license from the Catholic Church (an idea rejected in the end), but as early as the 15th century some nobles refused to have printed books in their libraries, thinking that to do so would sully their valuable handcopied manuscripts. Similar resistance was later encountered in much of the Islamic world, where calligraphic traditions were extremely important, and also in the Far East.

Despite this resistance, Gutenberg's printing press spread rapidly, and within thirty years of its invention, towns and cities across Europe had functional printing presses. Johann Heynlin, for example, introduced the first press to Paris in 1470. The city of Tübingen saw its first printed work, a commentary by Paul Scriptoris, in 1498. It has been suggested that this rapid expansion shows not only a higher level of industry (fueled by the high-quality European paper mills that had been opening over the previous century) than expected, but also a significantly higher level of literacy than has often been estimated.

The first printing press in a Muslim territory opened in Andalusia (now Spain) in the 1480s. This printing press was run by a family of Jewish merchants who printed texts with the Hebrew script. After the reconquista in the 1490s, the press was moved from Granada to Constantinople (now Istanbul) (a popular destination for thousands of Andalusian Jews).

Effects of printing on culture

The discovery and establishment of the printing of books with movable type marks a paradigm shift in the way information was transferred in Europe. The impact of printing is comparable to the development of language, and the invention of the alphabet, as far as its effects on the society. It is, however, important to note that there has been much recent doubt about the dominance of print. Handwritten manuscripts continued to be produced, and the influence of the printed word on oral communication meant that no one form of communication could dominate.

They also led to the establishment of a community of scientists (previously scientists worked in isolation from each other) who could easily communicate their discoveries, bringing on the scientific revolution. Although early texts were printed in Latin, books were soon produced in common European vernacular, leading to the decline of the Latin language.

Because of the printing press, authorship became more meaningful. It was suddenly important who had said or written what, and what the precise formulation and time of composition was. This allowed the exact citing of references, producing the rule, "One Author, one work (title), one piece of information" (Giesecke, 1989; 325). Before, the author was less important, since a copy of Aristotle made in Paris might not be identical to one made in Bologna. For many works prior to the printing press, the name of the author was entirely lost.

Because the printing process ensured that the same information fell on the same pages, page numbering, tables of contents, and indices became common. The process of reading was also changed, gradually changing from oral readings to silent, private reading. This gradually raised the literacy level as well, revolutionizing education.

It can also be argued that printing changed the way Europeans thought. With the older illuminated manuscripts, the emphasis was on the images and the beauty of the page. Early printed works emphasized principally the text and the line of argument. In the sciences, the introduction of the printing press marked a move from the medieval language of metaphors to the adoption of the scientific method.

In general, knowledge came closer to the hands of the people, since printed books could be sold for a fraction of the cost of illuminated manuscripts. There were also more copies of each book available, so that more people could discuss them. Within 50-60 years, the entire library of "classical" knowledge had been printed on the new presses (Eisenstein, 1969; 52). The spread of works also led to the creation of copies by other parties than the original author, leading to the formulation of copyright laws. Furthermore, as the books spread into the hands of the people, Latin was gradually replaced by the national languages. This development was one of the keys to the creation of modern nations.

Some theorists, such as Marshall McLuhan, Elizabeth Eisenstein, Kittler, and Giesecke, see an "alphabetic monopoly" as having developed from printing, removing the role of the image from society. Other authors stress that printed works themselves are a visual medium. However, the fact that blind people can "read" and that there is special printing and publishing for the blind refutes the claim that printing and printed works necessarily create and exist in a visual medium. (See the article Visual Culture for further discussion of this.)

The art of book printing

For years, book printing was considered a true art form. Typesetting, or the placement of the characters on the page, including the use of ligatures, was passed down from master to apprentice. In Germany, the art of typesetting was termed the "black art." It has largely been replaced nowadays by computer typesetting programs, which make it possible to get similar results with less human involvement.

Some few practitioners continue to print books the way Gutenberg did. For example, there is a yearly convention of traditional book printers in Mainz, Germany.

Printing in the industrial age

The Gutenberg press was much more efficient than manual copying, and as testament to its effectiveness, it was essentially unchanged from the time of its invention until the Industrial Revolution, some 300 years later. The "old style" press (as it was termed in the nineteenth century) was constructed of wood and could produce 240 impressions per hour of simple work using a well experienced two-man crew.

The invention of the steam powered printing press, credited to Friedrich Koenig and Andreas Friedrich Bauer in 1812, made it possible to print over a thousand copies of a page per hour.

Koenig and Bauer sold two of their first models to The Times in London in 1814, capable of 1,100 impressions per hour. The first edition so printed was on November 28, 1814. Koenig and Bauer went on to perfect the early model so that it could print on both sides of a sheet at once. This began to make newspapers available to a mass audience (which in turn helped spread literacy), and from the 1820s changed the nature of book production, forcing a greater standardization in titles and other metadata.

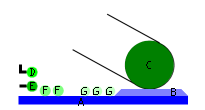

Koenig and Bauer's press was improved by Applegath and Cooper. The diagram indicates the principle operation of a Cooper and Applegath's Single Machine. The press is built up from a large flat inking table (A) which moves regularly back and forth, the form (B) on the table holds the type. The paper travels clockwise round a large cloth covered cylinder, the impression roller (C), and is pressed against the table. The ductor roller (D) rotates and so draws ink from the attached reservoir. The ink passes from the ductor roller to the vibrating roller (E), this moves, on its arms, in a regular motion between the ductor roller and the table. The ink is spread thinly and evenly by the distributing rollers (F) and then, as the table moves, passes onto the inking rollers (G). The axles of the inking rollers rest in groves, allowing them to rise and fall, they are also position at a slight angle to the table to improve ink distribution. As the table continues to move the form passes alternately under the inking rollers, twice, and then under the impression roller.

Later on in the middle of the 19th century the rotary press (invented in 1833 in the United States by Richard M. Hoe) allowed millions of copies of a page in a single day. Mass production of printed works flourished after the transition to rolled paper, as continuous feed allowed the presses to run at a much faster pace.

Also, in the middle of the nineteenth century, there was a separate development of jobbing presses, small presses capable of printing small-format pieces such as billheads, letterheads, business cards, and envelopes. Jobbing presses were capable of quick set-up (average makeready time for a small job was under 15 minutes) and quick production (even on treadle-powered jobbing presses it was considered normal to get 1,000 impressions per hour [iph] with one pressman, with speeds of 1,500 iph often attained on simple envelope work). Job printing emerged as a reasonably cost-effective duplicating solution for commerce at this time.

Movable type has been credited as being the single most important invention of the second millennium.

Methods of Printing Used Today

- Offset lithography offsets ink from metal plates to a rubber blanket (cylinder) to the paper. This is the most common printing process today; it can be thought of as the workhorse of the industry. Most books and newspapers are printed using this process.

- Letterpress is the original process founded by Gutenberg in 1440. This is sometimes known as relief printing because, as in a rubber stamp, the images on the printing plate are higher than the surface. Fine letterpress printing is declining in use and is being done by fewer and fewer printers.

- Engraving produces the sharpest image of all and is often used for fine stationery. The image feels indented

- Thermography, or raised printing, is less expensive than engraving. This uses a special powder that can be adhered to any color ink. It is mainly used for stationery products.

- Embossing is a special printing process that makes an impression into thick paper over printed type or a design. The impression may be concave or convex.

- Reprographics is a general term covering copying and duplicating. In-house copying departments and copy shops or quick-printing shops that take your originals and make duplicates of them use reprographics. This is sometimes known as photocopying or xerographic printing. Most often this process uses electrostatic printing, in which toner sticks to a charged drum and is thermally fused on to a page. Electrostatic printing is very good and very fast for very short printing runs, where a single copy or a few copies of an existing document are needed. Today it can be done in color too but at considerably greater per-copy cost than black and white. Paper of any color can be used, for either black or color copying.

- Gravure printing, also known as intaglio, is a high quality and expensive printing technique that uses direct contact between an etched copper plate and the paper. While the plate has a relatively high cost, this technique is the best way to print high quality, large volume materials such as brochures, magazines, annual reports and mail order catalogues. There are sheet-fed and roll-fed gravure printing processes; the latter is often called rotogravure.

- Screen printing is also known as silk-screening. In this process ink is forced through a screen following a stencil pattern. Each color of ink requires a separate stencil. It is used for such things as ring binders, t-shirts, bumper stickers, billboards, and floor tiles.

- Flexography is a special type of printing for packaging products. The plates used are flexible. Products using such printing include cardboard boxes, grocery bags, gift wrap, and can and bottle labels.

- Digital Printing is the newest printing process. It includes all processes that use digital imaging to create printed pieces. Desktop printing and publishing use this. The process does not use film. This is the best choice for short-run, fast-turnaround jobs. Past limitations have included color, paper choices, and quality, but the technology is changing and expanding so rapidly that those limitations are disappearing. In addition, many of the present-day digital printers can also print digital images and digital photographs of extremely high quality.

- Inkjet and bubble-jet technology, in which ink is sprayed onto the paper by the printing machine, is used in most of today's low to moderate cost computer and digital printers. This is used mostly for small-volume jobs. The quality of ink jet printers and printing can range from ordinary or mediocre to very high.

- Heat transfer printing is used modern receipt printers (for receipts made at point of sale in grocery stores, department stores, and elsewhere), and was used in old fax machines. This method applies heat to special paper, which turns black as directed to form the printed image.

- Hot wax dye transfer is used for batik dye printing of fabrics and other media.

- Laser printing is mainly used in offices and for transactional printing (such as bills and bank documents). Laser printers are usually much faster, producing more sheets per minute, than inkjet printers, but they are also usually considerably more expensive in initial cost than inkjet printers.

Today's state-of-the-art presses and printing systems often mix several printing techniques. So, for example, there may be an offset machine with a flexography section for the varnishing of the product being printed, or a digital printing unit combined with some other technique.

Obsolete Printing Processes

There are a number of now-obsolete printing processes. One was hot-lead Linotype, once used to print newspapers. In that process, compositors worked on Linotype machines that melted lead metal to make type according to the information the operator put into the machine. After the print run of an issue of the newspaper was completed, the lead was reclaimed, melted, and used for the next composition process.

In the early days of the personal computer, the printers used were based on typewriter technology, using a "daisy wheel" or other form of impact printing. Dot matrix printers were also widely used because they were cheaper and faster than daisy wheel or other typewriter-like printers. That technology is now obsolete, having been succeeded by laser, ink jet, and other types of computer-based printers.

Prior to the introduction of inexpensive photocopying, the use of machines such as the "spirit duplicator," "hectograph," and "mimeograph" was common; those techniques and equipment are now obsolete.

Digital Printing

Printing at home or in an office or engineering environment can be subdivided into:

- small format (up to ledger size paper)

- wide format (up to 3 feet (or 914 mm) wide rolls of paper).

Beyond that, there are the following methods:

- heat transfer (like old facimile machines or even modern receipt printers that apply heat to special paper, which turns black as directed to form the printed image)

- blueprint (chemical process)

- inkjet (including bubble-jet - where ink is sprayed onto the paper to create the desired image)

- laser (where toner consisting primarily of polymer with pigment of the desired colours is melted and applied directly to the paper to create the desired image.)

Vendors typically stress the total cost to operate the equipment, involving complex calculations that include all cost factors involved in the operation as well as the capital equipment costs, amortization, etc. For the most part, toner systems beat inkjet in the long run, whereas inkjets are less expensive in the initial purchase price. Inkjet systems tend to be more adaptable and able to print more different kinds of things, including printing in many colors, than laser and toner systems.

Professional digital printing (using toner) primarily uses an electrical charge to transfer toner or liquid ink to the substrate it is printed on. Digital print quality has steadily improved from color and black & white copiers to sophisticated color digital presses like the Xerox iGen3, the Kodak Nexpress and the HP Indigo series presses. The iGen3 and Nexpress use toner particles and the Indigo uses liquid ink. All three are made for small runs and variable data, and rival offset in quality. Digital offset presses are called direct imaging presses; although these receive computer files and automatically turn them into print-ready plates, they cannot do variable data.

Small press and "fanzines" generally use digital printing or, more rarely, xerography.

Topics in Printing Today

- Almost all personal computers and almost all offices now have printers and, for offices, sometimes elaborate printing networks connected with them. These printers and printing systems almost always now use ink jet or laser printers.

- The US Government printing office is the printing arm of the US government. It is one of the largest printing operations in the world.

- For money and postage stamps, it is the printing by the appropriate authority, not the paper itself, that creates the value. In the United States this printing is done by the US Bureau of Engraving and Printing. Its website is: http://www.bep.treas.gov/

- There are thousands of different printers available today. The Linux website database, for example, contains 2270 printers – but that was some time ago, so there are no doubt several hundred more by now!

- Special printing is done for the blind. In America it is done by the American Printing House for the Blind. Their website is: http://www.aph.org/

- Numerous accounts of the consequences of printing are available on the Internet. One is “Printing: Renaissance and Reformation” The website is: http://www.sc.edu/library/spcoll/sccoll/renprint/renprint.html

- There are numerous websites devoted to the history of printing. One is: http://communication.ucsd.edu/bjones/Books/booktext.html

- The role of printing – especially the printing of propaganda images in addition to text – was central in spreading the Protestant Reformation. A website on this topic is: http://communication.ucsd.edu/bjones/Books/luther.html

- Although books, newspapers, and magazines may be the first things that come to mind, there is a great deal of printing of other things, in addition to money, postage stamps, and all kinds of financial instruments such as checks, stock certificates, cerrtificates of deposit, and so on. The list includes brochures, flyers, business cards, catalogs, folders, leaflets, printing on packaging and shopping bags, maps, and other things.

- The U.S. Congress has a Joint (House and Senate) Committee on Printing. Among other things, it oversees the U.S. government Printing Office. Its website is: http://communication.ucsd.edu/bjones/Books/booktext.html

- Printing and elections: Is a paper trail – i.e. a printed record – needed for each vote in order to prevent fraud and mistakes when electronic voting is used?

- Many large companies, such as IBM, now offer comprehensive printing systems and machinery for office and other printing needs. See, for example, the IBM website: http://www.printers.ibm.com/internet/wwsites.nsf/vwwebpublished/main_ww

- The International Internet Printing Protocol gives standards and rules so that all the world’s computers and printers can work together on the Internet. Its website: http://www.pwg.org/ipp/

- The Graphic Arts Information Network disseminates information about printing and the graphic arts. Its website is: http://www.gain.net/eweb/StartPage.aspx

- There is The International Printing Museum, located at 315 Torrance Blvd., Carson, CA 90745. Its website: http://www.printmuseum.org/

- There are various magazines and journals devoted to printing and the printing industry. One is Printing Impressions. Its website: http://www.piworld.com/

- Today’s office printing systems can handle inputs from many different computers, and produce output that conforms to the specifications and needs of the various inputs. See, for example, the website: http://www.freebsd.org/doc/en_US.ISO8859-1/books/handbook/printing.html

See also

- Color printing

- Printing press

- Flexography

- Intaglio

- Typography

- Johannes Gutenberg

- Paper

- printmaking

- Printmaking

- Anilox

References

ISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Fontaine, Jean-Paul. L'aventure du livre: Du manuscrit medieval a nos jours. Paris: Bibliotheque de l'image, 1999. (in French)

- Nesbitt, Alexander. The History and Technique of Lettering. New York: Dover Books, 1957.

- Saunders, Gill and Rosie Miles. Prints Now : Directions and Definitions. Victoria and Albert Museum (May 1, 2006) ISBN 1851774807

- Steinberg, S.H. Five Hundred Years of Printing. London and Newcastle: The British Library and Oak Knoll Press, 1996.

- Tam, Pui-Wing. "The New Paper Trail." The Wall Street Journal Online, February 13, 2006, Sec.R8

- Woong-Jin-Wee-In-Jun-Gi #11 Jang Young Sil by Baek Sauk Gi. Woongjin Publishing Co., Ltd., 1987, 61.

External links

All links retrieved November 30, 2022.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.

↧ Download as ZWI file | Last modified: 02/03/2023 20:06:41 | 89 views

☰ Source: https://www.newworldencyclopedia.org/entry/Printing | License: CC BY-SA 3.0

ZWI signed:

ZWI signed:

KSF

KSF