Dark Ages

From Nwe

From Nwe In historiography the phrase the Dark Ages (or Dark Age) is most commonly known in relation to the European Early Middle Ages (from about 476 C.E. to about 1000 C.E.).

This concept of a "Dark Age" was first created by Italian humanists and was originally intended as a sweeping criticism of the character of Vulgar Latin (Late Latin) literature. Later historians expanded the term to include not only the lack of Latin literature, but a lack of contemporary written history and material cultural achievements in general. Popular culture has further expanded on the term as a vehicle to depict the Middle Ages as a time of backwardness, extending its derogatory use and expanding its scope. The rise of archaeology and other specialties in the twentieth century has shed much light on the period and offered a more nuanced understanding of its positive developments. Other terms of periodization have come to the fore: Late Antiquity, the Early Middle Ages, and the Great Migrations, depending on which aspects of culture are being emphasized.

Most modern historians dismiss the notion that the era was a "Dark Age" by pointing out that this idea was based on ignorance of the period combined with popular stereotypes; many previous authors would simply assume that the era was a dismal time of violence and stagnation and use this assumption to prove itself.

In Britain and the United States, the phrase "Dark Ages" has occasionally been used by professionals, with severe qualification, as a term of periodization. This usage is intended as non-judgmental and simply means the relative lack of written record, "silent" as much as "dark." On the other hand, this period in Europe did see a retreat from the classical worldview as political units became smaller and smaller and more competitive. Learning was not highly valued by aristocrats who saw scholarship as the preserve of the clerical profession. Some classical Greek scholarship was lost to Europe at this time. Knights learned to fight, not to read. Toward the end of this period, some classical Greek sources were rediscovered as part of the legacy that the Arabs had preserved. This encouraged Europeans to again see themselves within the context of a larger humanity, with shared aspirations, hopes, and fears. The ideal of a common world order, known earlier in the European space when it had been more or less united under Roman rule, was consequently reborn.

Petrarch and the "Dark Ages"

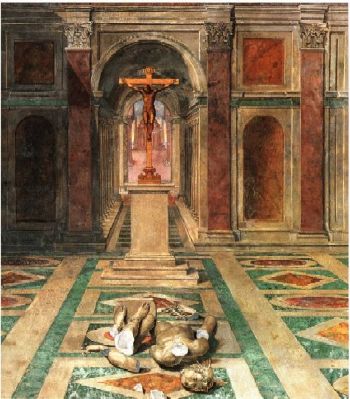

It is generally accepted that the term "Dark Ages" was invented by Petrarch in the 1330s. Writing of those who had come before him, he said that "amidst the errors there shone forth men of genius, no less keen were their eyes, although they were surrounded by darkness and dense gloom."[1] Christian writers had traditional metaphors of "light versus darkness" to describe "good versus evil." Petrarch was the first to co-opt the metaphor and give it secular meaning by reversing its application. Classical Antiquity, so long considered the "dark age" for its lack of Christianity, was now seen by Petrarch as the age of "light" because of its cultural achievements, while Petrarch's time, lacking such cultural achievements, was now seen as the age of darkness.

Why did Petrarch call it an age of darkness? Petrarch spent much of his time traveling through Europe rediscovering and republishing the classic Latin and Greek texts. He wanted to restore the classical Latin language to its former purity. Humanists saw the preceding nine hundred year period as a time of stagnation. They saw history unfolding not along the religious outline of St. Augustine's Six Ages of the World (from Adam to Noah, from Noah to Abraham, from Abraham to David, from David to the exile of the Hebrews in Babylon, from the return to the time of Jesus, the Christian era) but in cultural (or secular) terms, through the progressive developments of Classical ideals, literature, and art.

Petrarch wrote that history had had two periods: the Classic period of the Romans and Greeks, followed by a time of darkness, in which he saw himself as still living. In the conclusion of his epic Africa, he wrote:

My fate is to live among varied and confusing storms. But for you perhaps, if as I hope and wish you will live long after me, there will follow a better age. This sleep of forgetfulness will not last forever. When the darkness has been dispersed, our descendants can come again in the former pure radiance.[1]

Humanists believed one day the Roman Empire would rise again and restore Classic cultural purity. The concept of the European Dark Ages thus began as an ideological campaign by humanists to promote Classical culture, and was therefore not a neutral historical analysis. It was invented to express disapproval of one period in time, and the promotion of another.

By the late fourteenth and early fifteenth century, humanists such as Leonardo Bruni believed they had attained this new age, and a third, Modern Age had begun. The age before their own, which Petrarch had labeled "Dark," had thus become a "Middle" Age between the Classic and the Modern. The first use of the term "Middle Age" appears with Flavio Biondo around 1439.

The Dark Ages Concept After the Renaissance

Historians prior to the twentieth century wrote about the Middle Ages with a mixture of positive and negative (but mostly negative) sentiment.

Reformation

During the Protestant Reformation of the sixteenth century, Protestants wrote of it as a period of Catholic corruption. Just as Petrarch's writing was not an attack on Christianity per se—in addition to his humanism he was deeply occupied with the search for God—neither of course was this an attack on Christianity, but the opposite: a drive to restore what Protestants saw as a "purer" Christianity. In response to these attacks Roman Catholic reformers developed a counter image, depicting the age as a period of social and religious harmony, and not "dark" at all.

Enlightenment

During the seventeenth and eighteenth century, in the Age of Enlightenment, religion was seen as antithetical to reason. Because the Middle Age was an "Age of Faith" when religion reigned, it was seen as a period contrary to reason, and thus contrary to the Enlightenment. Immanuel Kant and Voltaire were two Enlightenment writers who were vocal in attacking the religiously dominated Middle Ages as a period of social decline. Many modern negative conceptions of the age come from Enlightenment authors.

Yet just as Petrarch, seeing himself on the threshold of a "new age," was criticizing the centuries up until his own time, so too were the Enlightenment writers criticizing the centuries up until theirs. These extended well after Petrarch's time, since religious domination and conflict were still common into the seventeenth century and even beyond, albeit diminished in scope.

Consequently an evolution had occurred in at least three ways. Petrarch's original metaphor of "light versus dark" had been expanded in time, implicitly at least. Even if the early humanists after him no longer saw themselves as living in a "dark" age, their times were still not "light" enough for eighteenth century writers who saw themselves as living in the real "age of Enlightenment," while the period covered by their own condemnation had extended and was focused also on what we now call Early Modern times. Additionally, Petrarch's metaphor of "darkness," which he used mainly to deplore what he saw as a lack of secular achievements, was now sharpened to take on a more explicitly anti-religious meaning in light of the draconian tactics of the Catholic clergy.

In spite of this, the term "Middle" Ages, used by Biondo and other early humanists after Petrarch, was the name in general use before the eighteenth century to denote the period up until the Renaissance. The earliest recorded use of the English word "medieval" was in 1827. The term "Dark Ages" was also in use, but by the eighteenth century it tended to be confined to the earlier part of this "medieval" period. Starting and ending dates varied: the "Dark Ages" were considered by some to start in 410, by others in 476 when there was no longer an emperor in Rome itself, and to end about 800 at the time of the Carolingian Renaissance under Charlemagne, or to extend through the rest of the first millennium up until about the year 1000.

Romantics

In the early nineteenth century, the Romantics reversed the negative assessment of Enlightenment critics. The word "Gothic" had been a term of opprobrium akin to "Vandal," until a few self-confident mid-eighteenth century English "goths" like Horace Walpole initiated the Gothic Revival in the arts, which for the following Romantic generation began to take on an idyllic image of the "Age of Faith." This image, in reaction to a world dominated by Enlightenment rationalism in which reason trumped emotion, expressed a romantic view of a Golden Age of chivalry. The Middle Ages were seen with romantic nostalgia as a period of social and environmental harmony and spiritual inspiration, in contrast to the excesses of the French Revolution and the environmental and social upheavals and sterile utilitarianism of the emerging industrial revolution. The Romantics' view of these earlier centuries can still be seen in modern-day fairs and festivals celebrating the period with costumes and events.

Just as Petrarch had turned the meaning of "light versus darkness" on its head, so had the Romantics turned the judgment of Enlightenment critics. However, the period idealized by the Romantics focused largely on what is now called the High Middle Ages, extending into Early Modern times. In one respect this was a reversal of the religious aspect of Petrarch's judgment, since these later centuries were those when the universal power and prestige of the Church was at its height. To many users of the term, the scope of the "Dark Ages" was becoming divorced from this period, now denoting mainly the earlier centuries after the fall of Rome.

Modern Academic Use

When modern scholarly study of the Middle Ages arose in the nineteenth century, the term "Dark Ages" was at first kept with all its critical overtones. Although it was never the more formal term (universities named their departments "medieval history," not "dark age history"), it was widely used, including in such classics as Gibbon's The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire, where it expressed the author's contempt for "priest-ridden," superstitious, dark times. However the early twentieth century saw a radical re-evaluation of the Middle Ages, and with it a calling into question of the terminology of darkness. The historian Denys Hay spoke ironically of "the lively centuries which we call dark."[2] It became clear that serious scholars would either have to redefine the term or abandon it.

When the term "Dark Ages" is used by historians today, it is intended to be neutral, namely to express the idea that the events of the period often seem "dark" to us, due to the lack of historical records compared with later times. The darkness is ours, not theirs. However, since there is no shortage of information on the High and Late Middle Ages, this required a narrowing of the reference to the Early Middle Ages. Late fifth and sixth century Britain for instance, at the height of the Saxon invasions, might well be numbered among "the darkest of the Dark Ages," with the equivalent of a near-total news blackout compared with either the Roman era before or the centuries that followed. Further east the same was true in the formerly Roman province of Dacia, where history after the Roman withdrawal went unrecorded for centuries as Slavs, Avars, Bulgars, and others struggled for supremacy in the Danube basin; events there are still disputed. However, at this time the Byzantine Empire and the Abbasid Caliphate experienced ages that were golden rather than dark; consequently, this usage of the term must also differentiate geographically. Ironically, while Petrarch's concept of a "Dark Age" corresponded to a mostly "Christian" period following pagan Rome, the neutral use of the term today applies mainly to those cultures least Christianized, and thus most sparsely covered by the Church's historians.

However, from the mid-twentieth century onward an increasing number of scholars began to critique even this non-judgmental use of the term. There are two main criticisms. Firstly, it is questionable whether it is possible to use the term "dark ages" effectively in a neutral way; scholars may intend it that way, but this does not mean that ordinary readers will understand it so. Secondly, the explosion of new knowledge and insight into the history and culture of the Early Middle Ages which twentieth century scholarship has achieved means that these centuries are no longer dark even in the sense of "unknown to us." Consequently, many academic writers prefer not to use the phrase at all.

Modern Popular Use

In modern times, the term "Dark Ages" is still used in popular culture. Petrarch's ideological campaign to paint the Middle Ages in a negative light worked so well that "Dark Ages" is still in popular use nearly seven hundred years later. The humanists' goal of reviving and revering the classics of antiquity was institutionalized in the newly forming universities at the time, and the schools over the centuries have remained true to their humanist roots. Students of education systems today are familiar with the canon of Greek authors, but few are ever exposed to the great thinkers of the Middle Ages such as Peter Abelard or Sigerus of Brabant. While the classics programs remain strong, students of the Middle Ages are not nearly as common. For example the first medieval historian in the United States, Charles Haskins, was not recognized until the early twentieth century, and the number of students of the Middle Ages remains to this day very small compared to the classics.

Historians today believe that the negative connotations of the word "dark" in "Dark Ages" negates its usefulness as a description of history. Yet Petrarch's concept of it, like that of other early humanists after him, as a discrete period distinct from our "Modern" age, has endured, and the term still finds use, through various definitions, both in popular culture and academic discourse.

Quotes

- "What else, then, is all history, but the praise of Rome?"—Petrarch

- "Each famous author of antiquity whom I recover places a new offence and another cause of dishonour to the charge of earlier generations, who, not satisfied with their own disgraceful barrenness, permitted the fruit of other minds, and the writings that their ancestors had produced by toil and application, to perish through insufferable neglect. Although they had nothing of their own to hand down to those who were to come after, they robbed posterity of its ancestral heritage."—Petrarch

- "The Middle Ages is an unfortunate term. It was not invented until the age was long past. The dwellers in the Middle Ages would not have recognized it. They did not know that they were living in the middle; they thought, quite rightly, that they were time's latest achievement."—Morris Bishop[3]

Notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Theodore E. Mommsen, Petrarch's Conception of the 'Dark Ages' Speculum 17(2) (April, 1942): 226-242. Retrieved January 10, 2022.

- ↑ Denys Hay, Annalists and Historians (Methuen & Co. Ltd, 1977, ISBN 978-0416811803), 50.

- ↑ Morris Bishop, The Middle Ages (Mariner Books, 2001, ISBN 978-0618057030), 7.

References

ISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Bishop, Morris. The Middle Ages. Mariner Books, 2001 (original 1968). ISBN 978-0618057030

- Black, Winston. The Middle Ages: Facts and Fictions. ABC-CLIO, 2019. ISBN 978-1440862311

- Hay, Denys. Annalists and Historians. Methuen & Co. Ltd, 1977. ISBN 978-0416811803

- Mommsen, Theodore E. Petrarch's Conception of the 'Dark Ages' Speculum 17(2) (April, 1942): 226-242. Retrieved January 10, 2022.

- Oman, Charles. The Dark Ages 476-918 C.E. Independently published, 2017 (original, 1893). ISBN 1973427370

External links

All links retrieved June 25, 2022.

- Why the Middle Ages are called the Dark Ages Medievalists.

- 6 Reasons the Dark Ages Weren’t So Dark History.com.

- Why It’s Time to Shed Some Light on History’s ‘Dark Ages’ TIME

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.

↧ Download as ZWI file | Last modified: 02/04/2023 01:44:12 | 56 views

☰ Source: https://www.newworldencyclopedia.org/entry/Dark_Ages | License: CC BY-SA 3.0

ZWI signed:

ZWI signed:

KSF

KSF