Jalisco

From Handwiki

From Handwiki Jalisco | |

|---|---|

State | |

| Free and Sovereign State of Jalisco Estado Libre y Soberano de Jalisco (Spanish) | |

Flag  Coat of arms | |

| Motto(s): Jalisco es México (English: "Jalisco is Mexico") | |

| Anthem: "Himno del estado de Jalisco" "Anthem of the state of Jalisco" | |

.svg.png) Jalisco within Mexico | |

| Coordinates: [ ⚑ ] : 20°40′35″N 103°20′45″W / 20.67639°N 103.34583°W | |

| Country | Mexico |

| Municipalities | 125 |

| Admission | 23 December 1823[2] |

| Order | 9th |

| Capital | Guadalajara |

| Government | |

| • Body | Congress of Jalisco |

| • Governor | |

| • Senators[3] | 23px Veronica Delgadillo García |

| • Deputies[4] | Federal Deputies

|

| Area [5] | |

| • Total | 78,588 km2 (30,343 sq mi) |

| Ranked 7th | |

| Highest elevation [6] (Nevado de Colima) | 4,339 m (14,236 ft) |

| Population (2020)[7] | |

| • Total | 8,348,151 |

| • Rank | 3rd |

| • Density | 110/km2 (280/sq mi) |

| • Density rank | 11th |

| Demonym(s) | Jalisciense |

| GDP [8] | |

| • Total | MXN 2.146 trillion (US$106.8 billion) (2022) |

| • Per capita | (US$12,412) (2022) |

| Time zone | UTC−6 (CST) |

| Postal code | 44-49 |

| Area code | Area codes 1, 2 and 3

|

| ISO 3166 code | MX-JAL |

| HDI | |

| Website | {{{1}}} |

Jalisco (/xəˈliːskoʊ/, also /xɑː-, xəˈlɪskoʊ/,[9][10] Spanish: [xaˈlisko] (![]() listen)), officially the Free and Sovereign State of Jalisco (Spanish: Estado Libre y Soberano de Jalisco [esˈtaðo ˈliβɾej soβeˈɾano ðe xaˈlisko]), is one of the 31 states which, along with Mexico City, comprise the 32 Federal Entities of Mexico. It is located in western Mexico and is bordered by six states, Nayarit, Zacatecas, Aguascalientes, Guanajuato, Michoacán, and Colima. Jalisco is divided into 125 municipalities, and its capital and largest city is Guadalajara.

listen)), officially the Free and Sovereign State of Jalisco (Spanish: Estado Libre y Soberano de Jalisco [esˈtaðo ˈliβɾej soβeˈɾano ðe xaˈlisko]), is one of the 31 states which, along with Mexico City, comprise the 32 Federal Entities of Mexico. It is located in western Mexico and is bordered by six states, Nayarit, Zacatecas, Aguascalientes, Guanajuato, Michoacán, and Colima. Jalisco is divided into 125 municipalities, and its capital and largest city is Guadalajara.

Jalisco is one of the most economically and culturally important states in Mexico, owing to its natural resources as well as its long history and culture.[11] Many of the characteristic traits of Mexican culture, particularly outside Mexico City, are originally from Jalisco, such as mariachi, ranchera music, birria, tequila, jaripeo, etc., hence the state's motto: "Jalisco es México" (Jalisco is Mexico). Economically, it is ranked third in the country, with industries centered in the Guadalajara metropolitan area, the third largest metropolitan area in Mexico. The state is home to two significant indigenous populations, the Huichols and the Nahuas. There is also a significant foreign population, mostly from the United States and Canada, living in the Lake Chapala and Puerto Vallarta areas.[12][13][14]

Geography

With a total area of 78,599 square kilometers (30,347 sq mi), Jalisco is the seventh-largest state in Mexico, accounting for 4.1% of the country's territory.[15][16][17] The state is in the central western coast of the country, bordering the states of Nayarit, Zacatecas, Aguascalientes, Guanajuato, Colima and Michoacán with 342 kilometers (213 mi) of coastline on the Pacific Ocean to the west.[15][17]

Jalisco is made up of a diverse terrain that includes forests, beaches, plains, and lakes.[18] Altitudes in the state vary from 0 to 4,300 meters (0 to 14,110 ft) above sea level, from the coast to the top of the Nevado de Colima.[19][20] The Jalisco area contains all five of Mexico's natural ecosystems: arid and semi arid scrublands, tropical evergreen forests, tropical deciduous and thorn forests, grasslands and mesquite grasslands, and temperate forests with oaks, pines and firs.[20] Over 52% of the bird species found in Mexico live in the state, with 525, 40% of Mexico's mammals with 173 and 18% of its reptile species. There are also 7,500 species of veined plants. One reason for its biodiversity is that it lies in the transition area between the temperate north and tropical south. It also lies at the northern edge of the Sierra Madre del Sur and is on the Trans-Mexican Volcanic Belt, which provides a wide variety of ecological conditions from tropical rainforest conditions to semi arid areas to areas apt for conifer forests.[21]

Its five natural regions are: Northwestern Plains and Sierras, Sierra Madre Occidental, Central Plateau, Trans-Mexican Volcanic Belt, which covers most of the state, and the Sierra Madre del Sur.[19] It has an average altitude of 1,550 meters (5,090 ft) MASL, but ranges from 0–4,300 m (0–14,110 ft).[17] Most of the territory is semi-flat between 600–2,050 m (1,970–6,730 ft), followed by rugged terrain of between 900–4,300 m (2,950–14,110 ft) and a small percentage of flat lands between 0–1,750 m (0–5,740 ft). Principal elevations include the Nevado de Colima, the Volcán de Colima, the Sierra El Madroño, the Tequila Volcano, the Sierra Tapalpa, Sierra Los Huicholes, Sierra San Isidro, Sierra Manantlán, Cerro El Tigre, Cerro García, Sierra Lalo, Sierra Cacoma, Cerro Gordo, Sierra Verde, and the Sierra Los Guajolotes.[21]

Jalisco's rivers and streams eventually empty into the Pacific Ocean and are divided into three groups: the Lerma/Santiago River and its tributaries, rivers that empty directly into the Pacific and rivers in the south of the state.[21] Jalisco has several river basins with the most notable being that of the Lerma/Santiago River, which drains the northern and northeastern parts of the state.[19] The Lerma River enters extends from the State of Mexico and empties into Lake Chapala on the east side. On the west, water flows out in the Santiago River, which crosses the center of Jalisco on its way to the Pacific, carving deep canyons in the land.[20][21] Tributaries to the Santiago River include the Zula, the Verde River, the Juchipila and the Bolaños. About three quarters of the state's population lives near this river system.[21] In the southwest of the state, there are a number of small rivers that empty directly into the Pacific Ocean. The most important of these is the Ameca, with its one main tributary, the Mascota River. This river forms the state's border with Nayarit and empties into the Ipala Bay.[21] The Tomatlán, San Nicolás, Purificación, Marabasco-Minatitlán, Ayuquila, Tuxcacuesco, Armería and Tuxpan rivers flow almost perpendicular to the Pacific Ocean and drain the coastal area.[19] Another river of this group is the Cihuatlán River, which forms the boundary between Jalisco and Colima emptying into the Barra de Navidad Bay.[21] The southeastern corner belongs to the Balsas River basin.[19] This includes the Ayuqila and Tuxcacuesco, which join to form the Armería and the Tuxpan.[21]

The other main surface water is Lake Chapala, and is the largest and most important freshwater lake in Mexico, accounting for about half of the country's lake surface. The lake acts as a regulator of the flow of both the Lerma and Santiago Rivers.[21] There are a number of seasonal and salty lakes linking to form the Zacoalco-Sayula land-locked system.[19] There are other smaller lakes called Cajititlán, Sayula, San Marcos, and Atotonilco. Dams include the Cajón de Peña, Santa Rosa, La Vega, Tacotán and Las Piedras. Jalisco's surface water accounts for fifteen percent of the surface freshwater in Mexico.[21]

In 1987, four beaches in Jalisco were designated as federal marine turtle sanctuaries: El Tecuán, Cuitzmala, Teopa and Playón de Mismaloya, with an extension of 8 km (5.0 mi).[21] Playa Majahuitas is 27 km (17 mi) southwest of Puerto Vallarta with a rugged coastline, numerous inlets and outcroppings. The Cañon Submarino underwater canyon is located offshore. Chamela Bay has the greatest number of islets in Mexico, many of which are inhabited by numerous bird species.[22]

Jalisco has eight areas under conservation measures totaling 208,653.8 hectares. Two contains scientific research centers. These areas cover 4.8% of the state and only one, the Sierra de Manantlán Biosphere Reserve accounts for sixty percent of all legally protected land at 139,500 hectares. The other protected areas include the Chamela-Cuitzmala Bioshere Reserve (13,143 hectares), Volcán Nevado de Colima National Park (10,143 hectares), Bosque de la Primavera (30,500 hectares), Sierra de Quila (15,1923 hectares) and the Marine Turtle Protection Zone (175.8 hectares).[21]

Thirteen plant communities are present in the state. Forty five to fifty percent of the state is characterized by deciduous and sub-deciduous forests. They occur along the coastal plains as well as in canyons in the central part of the state from sea level to 1600masl. Some areas, scattered within the tropical sub-deciduous forest along the coastal plains, are dominated by palms. Conifer and oak forests are most common in the highlands between 800 and 3,400masl, covering about one fourth of the state's surface.[19] One major conifer and oak forest is the Primavera Forest.[20] Pine dominated areas in lower elevations are only found in the western corner of the state. Cloud and fir-dominated forests are restricted to ravines and protected steep slopes within the conifer and oak forest zones.[19] Jalisco's cloud forests include the Bosque de Maples and those on El Cerro de Manantlán.[20] Savannas are found between 400 and 800 meters above sea level in the area the slopes towards the Pacific Ocean. These grasslands are a transition area between the tropical sub-deciduous forest and oak forest. The thorn forest includes an area of the coastal plains in the western part of the state as well as an area dominated by mesquite within the tropical deciduous forest. Grasslands are restricted to the northeastern corner interspersed with xerophilous scrub. There are mangroves along the ocean where waves are gentle. Beach and frontal dune vegetation dominates the rest of the coastline.[19]

Climate

Most of the state has a temperate climate with Tropical humid summers. There is a distinct rainy season from June to October.[19] The climate can be divided into 29 different zones, from hot to cold and from very dry to semi moist. In most of the state, most of the rain falls between February.[21]

The coastal area receives the most precipitation and has the warmest temperatures, at an average of between 22 and 26 °C and an average precipitation of about 2,000 mm annually.[21] In the north and northwest, a dry climate predominates with average temperatures of between 10 and 18 °C, and average annual precipitation between 300 and 1,000 mm. The center of the state has three different climates, but all are mostly temperate with an average temperature of 19 °C and an average rainfall of between 700 and 1000 mm.[21] The northeastern corner and coastal plains of Tomatlán are the driest areas with less than 500 mm annually.[19] Los Altos de Jalisco region has a number of microclimates due to the rugged terrain. The area is mostly dry with an average temperature of 18 °C except in the north, where it fluctuates between 18 and 22 °C.[21] In the highlands, the average temperature is less than 18 °C.[19]

In various parts of the state there are areas with a semi-moist, temperate climate, some with average temperatures of between 10 and 18 °C and others of between 18 and 22 °C.[21]

In the highlands of the Sierra de Manantlán, Cacaola, Tepetates and Mascota near the coastal plains there is the most rainfall reaching 1600 mm per year. In the highlands, the average temperature is less than 18 °C.[19]

On 23 October 2015, Jalisco was hit by Hurricane Patricia. This was the second most intense hurricane ever registered and made landfall near Cuixmala, Jalisco. Though it began as a tropical storm, unusual environmental conditions strengthened Patricia to become a Category 5 Hurricane within 24 hours, with winds of 345 km/h (96 m/s; 214 mph).[23] The mountains surrounding the area of landfall acted as a barrier that weakened the hurricane before it finally hit ground at 150 mph (240 km/h). Security measures were implemented in time and Official Emergency Messages[24] were released to keep citizens and tourists in dangerous areas properly informed. Despite losing strength, Hurricane Patricia caused severe material damage, flooding and landslides; but there were no deaths reported related to the storm in any region affected.

Demographics

Largest cities

Largest cities or towns in Jalisco

Source:[25] | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rank | Municipality | Pop. | |||||||

Guadalajara Zapopan |

1 | Guadalajara | Guadalajara | 1,385,621 |  San Pedro Tlaquepaque  Tonalá | ||||

| 2 | Zapopan | Zapopan | 1,257,547 | ||||||

| 3 | San Pedro Tlaquepaque | Tlaquepaque | 640,123 | ||||||

| 4 | Tonalá | Tonalá | 442,440 | ||||||

| 5 | Puerto Vallarta | Puerto Vallarta | 224,166 | ||||||

| 6 | Hacienda Santa Fe | Tlajomulco de Zúñiga | 139,741 | ||||||

| 7 | Ciudad Guzmán | Zapotlán el Grande | 111,975 | ||||||

| 8 | Lagos de Moreno | Lagos de Moreno | 111,569 | ||||||

| 9 | Tepatitlán de Morelos | Tepatitlán | 98,842 | ||||||

| 10 | Ocotlán | Ocotlán | 94,978 | ||||||

| Historical population | ||

|---|---|---|

| Year | Pop. | ±% |

| 1895 | 1,114,765 | — |

| 1900 | 1,153,891 | +3.5% |

| 1910 | 1,208,855 | +4.8% |

| 1921 | 1,191,957 | −1.4% |

| 1930 | 1,255,346 | +5.3% |

| 1940 | 1,418,310 | +13.0% |

| 1950 | 1,746,777 | +23.2% |

| 1960 | 2,443,261 | +39.9% |

| 1970 | 3,296,586 | +34.9% |

| 1980 | 4,371,998 | +32.6% |

| 1990 | 5,302,689 | +21.3% |

| 1995 | 5,991,176 | +13.0% |

| 2000 | 6,322,002 | +5.5% |

| 2005 | 6,752,113 | +6.8% |

| 2010 | 7,350,682 | +8.9% |

| 2015 | 7,844,830 | +6.7% |

| 2020[7] | 8,348,151 | +6.4% |

As of 2020, the state population was 8,348,151,[26] the third most populated federal entity in Mexico—after the State of Mexico and Mexico City—with 6.5% of Mexico's total population.[16][27] Over half of the state's population lives in the Guadalajara metro area. Of the over 12,000 communities in the state, over 8,700 have a population of under fifty.[28] 87% of the population lives in urban centers compared to 78% nationally.[29]

Despite the fact that the number of children per woman has dropped by more than half from a high of 6.8 in 1970, the total population has grown from 5,991,175 in 1995 to the present number.[28] One important factor in population growth is migration into the state. Since 1995, over 22% of the state population was born somewhere else. About three quarters of these live in the Greater Guadalajara area. Most of those who migrate into the state are either from Michoacán, Mexico City, State of Mexico, Sinaloa, or Baja California.[28][30]

The state ranks third in socioeconomic factors. As of 2010, there were 1,801,306 housing units in the state. 94.2% have running water, 97.4% have sewerage, and 99% have electricity. 25% of households are headed by women, with 65.6% occupied by nuclear families. 22.2% are occupied by extended families.[31]

There is also emigration from the state, mostly to the United States. Jalisco is ranked seventh in Mexico for the number of people who leave for the United States.[28][32] As of 2000, 27 of every 1000 residents lived in the United States, higher than the national average of 16 per 1000.[30][failed verification] Those who stay within Mexico generally head to Nayarit, Baja California, Colima, Michoacán and Guanajuato.[30] There are no official numbers for ethnic groups but as of 2005, the state has a population of 42,372 people who spoke an indigenous language.[28] Eight out of every 1000 people speak an indigenous language, above the national average of six per 1000.[16] As of 2010, the most common indigenous language is Huichol with 18,409 speakers, followed by Nahuatl at 11,650, then Purépecha at 3,960 and variations of Mixtec at 2,001. In total, 51,702 people over the age of five speak an indigenous language, which is less than one percent of the total population of the state. Of these indigenous speakers, fourteen percent do not speak Spanish.[33] Municipalities with the highest indigenous population in general are Mezquitic, Zapopan and Guadalajara. Zapopan's and Guadalajara's indigenous population is mostly made up of those who have migrated to the area for work.[28]

The Huichols are concentrated in the municipalities of Mezquitic and Bolaños in the north of the state. In this same area are four of this ethnicity's most important ceremonial centers, San Andrés Cohamiata, Santa Catarina Cuexcomatitlán, San Sebastián Teponahuaxtlán and Tuxpan de Bolaños. The fifth, Guadalupe Octán, is in Nayarit.[28] The Huichols are of the same ethnic heritage as the Aztecs and speak a Uto-Aztecan language. They are best known for the preservation of their pre Hispanic shamanic traditions. The Huichol romanticize their past, when game was plentiful and they were free to roam the vast mountain ranges and deserts of their homeland. This was a time of freedom for them, before they became tethered to the growing of maize. Agriculture is difficult in the mountainous areas where they live. Elaborate ceremonies are enacted to help ensure crops’ success. There are three basic elements in Huichol religion, which are corn, deer and the peyote cactus. Peyote is obtained by a yearly pilgrimage to an area called Wirikuta, where it is harvested with great ceremony.[34]

Another distinct group living in the state is foreign temporary residents or expats, the overwhelming majority of which are from the United States and Canada, concentrated in and around the small town of Ajijic by Lake Chapala.[22] The Lake Chapala area has the largest population of Americans outside of the United States. The phenomenon began at the beginning of the 20th century. Cars with U.S. plates are not uncommon and many signs are in English and Spanish. There are no official numbers but the number of ex-pats in the area is estimated at 20,000. Half of these are from the US with most of the rest from Canada and some from European and Asian countries. Most are retirees, although there is a notable artist community. In the winter, the number of foreigners in the area can reach 50,000.[35] Another area popular with foreigners is Lagos de Moreno.[18]

According to the 2020 Census, 1.67% of Jalisco's population identified as Black, Afro-Mexican, or of African descent.[36]

Government and regions

The capital of the state is Guadalajara which is also its cultural and economic center. The state government consists of a governor, a unicameral legislature and a state judiciary branch.[26] The Guadalajara metropolitan area consists of the city along with seven other municipalities in the Center region of the state. This is the second most populous metro area in Mexico after that of Mexico City.[26] Six of the municipalities are considered to be the area's nucleus: Guadalajara, El Salto, Tlajomulco de Zúñiga, Tlaquepaque, Tonalá and Zapopan, with two others, Juanacatlán and Ixtlahuacán de los Membrillos as suburbs. These municipalities extend over an area of 2,734 km2 (1,055.60 sq mi) with a population density of 133.2 inhabitants per hectare (2005). The most highly concentrated municipality in the zone is the municipality of Guadalajara, followed by Zapopan.[26]

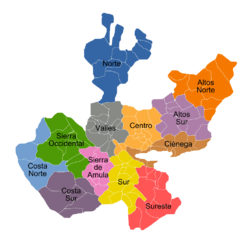

The state as a whole consists of 125 municipalities which were organized into twelve administrative regions in 1996:[37]

| # | Region | Seat | Area (km2)[38] | Area (%) | Population (2010)[38] | Population (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Norte | Colotlán | 10,305 | 12.9% | 78,835 | 1.1% |

| 2 | Altos Norte | Lagos de Moreno | 8,882 | 11.1% | 383,317 | 5.2% |

| 3 | Altos Sur | Tepatitlán de Morelos | 6,667 | 8.3% | 384,144 | 5.2% |

| 4 | Ciénega | La Barca | 4,892 | 6.1% | 503,297 | 6.8% |

| 5 | Sureste | Tamazula de Gordiano | 7,124 | 8.9% | 116,416 | 1.6% |

| 6 | Sur | Zapotlán el Grande | 5,650 | 7.1% | 332,411 | 4.5% |

| 7 | Sierra de Amula | El Grullo | 4,240 | 5.3% | 95,680 | 1.3% |

| 9 | Costa Norte | Puerto Vallarta | 5,985 | 7.5% | 300,760 | 4.1% |

| 10 | Sierra Occidental | Mascota | 8,381 | 10.5% | 61,257 | 0.8% |

| 11 | Valles | Ameca | 6,004 | 7.5% | 345,438 | 4.7% |

| 12 | Centro | Guadalajara | 5,003 | 6.2% | 4,578,700 | 62.3% |

| 13 | Costa Sur | Autlán de Navarro | 7,004 | 8.7% | 170,427 | 2.3% |

| Total | Jalisco | - | 80,137 | 100% | 7,350,682 | 100% |

Altos Norte has eight municipalities: Villa Hidalgo, Unión de San Antonio, Teocaltiche, San Juan de los Lagos, San Diego de Alejandría, Ojuelos de Jalisco, Lagos de Moreno and Encarnación de Díaz.[17]

Altos Sur consists of twelve municipalities: Yahualica de González Gallo, Valle de Guadalupe, Tepatitlán de Morelos, San Miguel el Alto, San Julián, San Ignacio Cerro Gordo, Mexticacán, Jesús María, Jalostotitlán, Cañadas de Obregón, Arandas and Acatic.[17]

The Centro Region consists of fourteen municipalities: Zapotlanejo, Zapopan, Villa Corona, Tonalá, Tlaquepaque, Tlajomulco de Zúñiga, San Cristóbal de la Barranca, Juanacatlán, Ixtlahuacán del Río, Ixtlahuacán de los Membrillos, Guadalajara, El Salto, Cuquío and Acatlán de Juárez.[17]

The Ciénega Region contains thirteen municipalities: Zapotlán del Rey, Tuxcueca, Tototlán, Tizapán El Alto, Poncitlán, Ocotlán, La Barca, Jocotepec, Jamay, Degollado, Chapala, Ayotlán and Atotonilco El Alto.[17]

The Costa Norte has three municipalities: Tomatlán, Puerto Vallarta and Cabo Corrientes.[17]

The Costa Sur has six municipalities: Villa Purificación, La Huerta, Cuautitlán de García Barragán, Cihuatlán, Casimiro Castillo and Autlán de Navarro.[17]

The Norte Region has ten municipalities: Villa Guerrero, Totatiche, Santa María de los Ángeles, San Martín de Bolaños, Mezquitic, Huejúcar, Huejuquilla El Alto, Colotlán, Chimaltitán, and Bolaños.[17]

The Sierra de Amula has eleven municipalities: Unión de Tula, Tuxcacuesco, Tonaya, Tenamaxtlán, Tecolotlán, Juchitlán, El Limón, El Grullo, Ejutla, Chiquilistlán and Atengo.[17]

The Sierra Occidental has eight municipalities: Talpa de Allende, San Sebastián del Oeste, Mixtlán, Mascota, Guachinango, Cuautla, Ayutla and Atenguillo.[17]

The Sur Region has sixteen municipalities: Amacueca, Atemajac de Brizuela, Atoyac, Gómez Farías, San Gabriel, Sayula, Tapalpa, Techaluta de Montenegro, Teocuitatlán de Corona, Tolimán, Tonila, Túxpan, Zacoalco de Torres, Zapotiltic, Zapotitlán de Vadillo, and Zapotlán el Grande.[17]

The Sureste Region has ten municipalities: Valle de Juárez, Tecalitlán, Tamazula de Gordiano, Santa María del Oro, Quitupan, Pihuamo, Mazamitla, La Manzanilla de La Paz, Jilotlán de los Dolores and Concepción de Buenos Aires.[17]

The Valles Region has fourteen municipalities: Teuchitlán, Tequila, Tala, San Martín Hidalgo, San Marco, San Juanito de Escobedo, Magdalena Municipality, Jalisco, Hostotipaquillo, Etzatlán, El Arenal, Cocula, Ameca, Amatitán and Ahualulco de Mercado.[17]

History

Nomenclature and seal

The name is derived from the Nahuatl Xalisco, which means "over a sandy surface".[11][39] Until about 1836, the name was spelled "Xalisco," with the "x" used to indicate the "sh" sound from Nahuatl. However, the modern Spanish based pronunciation is represented with a "j."[11] Jalisco is pronounced [xaˈlisko] or [haˈlisko], the latter pronunciation used mostly in dialects of southern Mexico, the Caribbean, much of Central America, some places in South America, and the Canary Islands and western Andalusia in Spain where [x] has become a voiceless glottal fricative ([h]).[40] The coat of arms for Guadalajara was adopted and adapted as the state seal since 1989 with minor changes to distinguish the two.[39] The nickname for people from Jalisco, "tapatío", derives from the Nahuatl word tapatiotl (the name of a monetary unit in pre-Columbian times); Franciscan Alonso de Molina wrote that it referred specifically to "the price of something purchased."[18]

Pre-Hispanic period

Nomadic peoples moving south arrived in the Jalisco area around 15,000 years ago.[41][42] Some of oldest evidence of human occupation is found around Zacoalco and Chapala lakes, which used to be connected. This evidence includes human and animal bones and tools made of bone and stone.[41] Other signs of human habitation include petroglyphs and cave paintings found at Cabo Corrientes, San Gabriel, Jesús María, La Huerta, Puerto Vallarta, Mixtlán, Villa Purificación, Casimiro Castillo, Zapotlán el Grande and Pihuamo.[43]

Agriculture began in the same region around 7,000 years ago, giving rise to the first permanent settlements in western Mexico.[41] Ceramics began to be produced about 3,500 years ago for both utilitarian and ceremonial purposes. The oldest pieces of Jalisco area pottery are called El Opeño, after an area near Zamora, Michoacán and Capacha after an area in Colima. The appearance of these styles indicates a certain specialization of labor, with distinct settled cultures established by 1000 BCE.[41] The earliest settled cultures were centered on the site of Chupícuaro, Guanajuato, which has a large zone of influence from Durango east, crossing through modern Jalisco's north. Sites related to these cultures have been found in Bolaños, Totoate, the Bolaños River Canyon and Totatiche as well as other locations in the Los Altos Region.[41] Cultures dating to the early part of the Christian era are distinguished by the use of shaft tombs, with major examples found in Acatlán de Juárez, El Arenal and Casimiro Castillo. The use of this type of tomb is unknown anywhere else in Mexico.[41][43] In the 7th century, Toltec and Teotihuacan influence is evident in the area, with a dominion called Xalisco established by the Toltecs in 618.[32][44] The dominion was established through the military domination of the weaker local groups. During this time, ceramics were improved and the working of gold, silver and copper appeared. More recent archeology of the area has produced evidence of larger cities, large scale irrigation and a kind of script used by various cultures of the area.[43] The Toltec influence had a strong influence over religious development with deities formalizing into gods recognized by the later Aztec civilization such as Tlāloc, Mictlāntēcutli and Quetzalcoatl.[41] A number of cities were built during this time, including Ixtepete, which show many features of Mesoamerican architecture such as the building of pyramid bases, temples and Mesoamerican ballcourts. However, these are sparse because there were very few communities of the size needed to support them. Stones used for building were often cut in angles and with relief such as those found in Tamazula and El Chanal, Colima. Ixtepete from the tenth century has talud/tablero construction showing Teotihuacan influence.[41] By 1112, the tribes dominated by the Toltecs rebelled and brought an end to the domination; however, the area would be conquered again in 1129, this time by the Chichimecas.[44]

By 1325, the Purépecha Empire had become dominant in parts of the state, but in 1510, the indigenous settlements of Zapotlán, Sayula and Zacoalco pushed back the Purépecha during the Salitre War.[43]

One reason for ancient civilizations in the area was the large deposits of obsidian and it was the center of the Teuchitlán culture.[20] Evidence of the most advanced pre Hispanic cultures are found in the center and south of the state. The most important site is Ixtepete in Zapopan which dates from between the 5th and 10th centuries and shows Teotihuacan influence. Other sites include Atitlán, El Mirador, El Reliz and Las Cuevas in San Juanito de Escobedo, Portezuelo in Ameca, Santa Cruz de Bárcenas in Ahualulco de Mercado, Santa Quitería, Huaxtla and Las Pilas in El Arenal, La Providencia, Laguna Colorada, Las Cuevas, El Arenal and Palacio de Oconahua in Etzatlán, Cerro de la Navaja, Huitzilapa and Xochitepec in Magdalena and the Ixtapa Ceremonial Center in Puerto Vallarta.[42]

Colonial period

Over its history, the Jalisco area has been occupied by a variety of ethnicities including the Bapames, Caxcans, Cocas, Guachichiles, Huichols, Cuyutecos, Otomis, Nahuas, Tecuexes, Tepehuans, Tecos, Purépecha, Pinomes, Tzaultecas and Xilotlantzingas. Some writers have also mentioned groups such as the Pinos, Otontlatolis, Amultecas, Coras, Xiximes, Tecuares, Tecoxines and Tecualmes.[43] When the Spanish arrived the main ethnic groups were the Cazcanes, who inhabited the northern regions near Teocalteche and the Lagos de Morenos, and the Huichols, who inhabited the northwest near Huejúcar and Colotlán. Other groups included the Guachichil in the Los Altos area, the Nahuatl speaking Cuyutecos in the west, the Tecuexes and Cocas near what is now Guadalajara, and the Guamares in the east near the Guanajuato border.[32]

Shortly after the conquest of the Aztecs in 1521, the Spanish pushed west.[44] They overpowered the Purépecha in Michoacán, converting their capital of Tzintzuntzan as a base to move further west. One reason for the push towards the Pacific was to build ships and shipping facilities in order to initiate trade with Asia. Another draw was to find more mineral wealth as the Purépecha had already developed copper working along with silver and gold.[45]

In 1522, Cristóbal de Olid was sent by Hernán Cortés northwest from Mexico City into Jalisco.[32] Other incursions were undertaken by Alonso de Avalos and Juan Alvarez Chico in 1521, Gonzalo de Sandoval in 1522, and Francisco Cortés de San Buenaventura in 1524.[43] The first area explored now belongs to the south of Jalisco down into what it now the state of Colima.[45] In 1529, the president of the First Audencia in New Spain, Nuño de Guzmán came west from Mexico City with a force of 300 Spanish and 6,000 Indian allies, traveling through Michoacán, Guanajuato, Jalisco and Sinaloa. At the end of 1531, Guzmán founded the Villa del Espíritu Santo de la Mayor Españas as the capital of the newly conquered western lands. The name was changed shortly thereafter to Santiago Galicia de Compostela.[43] In 1531, Guzmán ordered his chief lieutenant, Juan de Oñate, to found the Villa of Guadalajara, named after Guzmán's hometown in Spain. It was initially founded in what is now Nochistlán in Zacatecas. Construction began in 1532, but the small settlement came under repeated attacks from the Cazcanes, until it was abandoned in 1533. The town of Guadalajara would move four times in total before coming to its modern site in 1542.[32]

Most of Jalisco was conquered by Nuño de Guzmán, who then sent expeditions from there into Zacatecas and Aguascalientes in 1530.[44] The first encomiendas were granted to the Spanish conquistadors in Nueva Galicia by Nuño de Guzmán and later by Antonio de Mendoza.[45][46] Nuño de Guzmán founded five Spanish settlements, San Miguel, Chiametla, Compostela, Purificación and Guadalajara to form the first administrative structure of the area. However, most of these settlements were too small to support the grand plans of many Spanish in America and attracted few settlers. By the end of the early colonial period, all of these settlements either disappeared or were moved to other locations.[45] Guzmán was named the first governor of the region and Franciscans established monasteries in Tetlán and Ajijic.[44]

Guzmán was brutal to the local indigenous populations, sending many to slavery in the Caribbean and committing genocide in areas. This would eventually lead to his imprisonment in 1536 by viceroy Antonio de Mendoza.[32] However, not only Guzmán was to blame for subsequent indigenous hostility. The Spanish in Guadalajara and other locations began to take indigenous peoples as slaves in 1543.[44] These Spanish in the area were looking to enrich themselves as fast as possible, following the success of the same of those who arrived first to the Mexico City area. This led to abuses of the native populations, widespread corruption and confrontations between the Spanish and the indigenous and among the Spanish themselves.[46] Overwork and disease reduced the native population by about ninety percent between 1550 and 1650.[46]

This would begin a history of conflict and uprising in the Jalisco area which would last from the 16th century to the 1920s.[32][43] Early uprisings include that in Culiacán in 1533, of the Coaxicoria in 1538 and the Texcoixines and Caxcanes in 1541.[43] Subduing the indigenous peoples proved difficult in general due to a lack of large dominion to co-opt as was done in the Mexico City area. In the early colonial period, it was not certain that the Spanish could impose its language or culture onto the native population. The initial effect of colonization was the influence of Nahuatl, as mestizos and indigenous from central Mexico had a greater impact on the local populations than the sparse Spanish.[45][46]

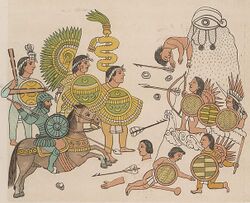

The most significant early revolt was the Mixtón Rebellion in 1541. United under a leader named Tenamaxtli, the indigenous of the Jalisco area laid siege to Guadalajara. The Spanish provincial government under Oñate could not withstand the assault and Pedro de Alvarado was sent to area from Mexico City but this initial attempt was thwarted. During a battle, a horse fell on Alvarado, mortally wounding him. Viceroy Mendoza then arrived with a force of 300 horsemen, 300 infantry, artillery and 20,000 Tlaxcalan and Aztec allies to recapture the territory held by the indigenous resistance.[32] The Mixtón War prompted Charles V to create the Audencia of Nueva Galicia which extended from Michoacán and into the present states of Jalisco, Colima, and parts of Zacatecas, Durango and Sinaloa.[32][45] An Indian Council was formed to advise the four members of the new Spanish government.[46] The area was called Nueva Galicia because the Crown wanted to reproduce in the new lands a territory similar to that of Spain.[45] The seat of this colony was moved to Guadalajara in 1561, and it was made independent of Mexico City in 1575.[44]

Most of the evangelization fell to regular clergy instead of monks.[46] The bishopric of Guadalajara was established by Pope Paul II in 1546.[44]

The Chichimeca War began in 1550. In 1554, the Chichimecas attacked a Spanish caravan of sixty wagons at the Ojuelos Pass, carrying off 30,000 pesos of clothing, silver and other valuables. At the end of the century, the Spanish were able to negotiate a peace with most.[32] There later uprisings such as in Guaynamota in 1584, in Acaponeta in 1593, one led by Cogixito in 1617, and one in Nostic in 1704. The last major colonial era insurrection occurred in 1801 led by an indigenous named Mariano.[43][44] The last of the Chichimeca groups were ultimately defeated in 1591.[44] However, these uprisings would gradually be overshadowed by the consolidation of political and economic power and peace treaties negotiated with indigenous groups such as the Coras and indigenous groups such as the Otomi were brought to settle.[32]

The province of Jalisco was separated from Michoacán in 1607 with the name of Santiago.[43][44]

Despite these conflicts, the 17th and 18th centuries brought development and economic prosperity to the region.[32] In the colonial period, Guadalajara grew as the center of an agricultural and cattle producing area.[18] Guadalajara grew from about 6,000 people in 1713 to 20,000 in mid century to 35,000 at the beginning of the 19th century.[47] The region's ceramic tradition began in the early colonial period, with native traditions superimposed by European ones. The center of ceramic production was Tonalá due to its abundance of raw materials. The Guadalajara tradition became famous enough for wares to be exported to other parts of New Spain and Europe.[46] The area was also important to the commerce of New Spain, as its strategic location funneled imported goods to other parts of the colony.[32]

In 1786, New Spain was reorganized into twelve "intendencias" and three provinces. The Intendencia of Guadalajara included what is now Jalisco, Aguascalientes, Nayarit and Colima.[43][44] Aguascalientes was separated from Jalisco in 1789.[43]

The University of Guadalajara was founded in 1792.[44]

Independence

.JPG)

At the beginning of the 19th century, Colima, parts of Zacatecas and the San Blas region (Nayarit) were still part of the Intendencia of Guadalajara.[47] The area had relative freedom from Spanish colonial authorities and prospered with fewer trade restrictions. This, along with lingering indigenous resentment to Spanish rule since the 16th century, led it to be sympathetic to insurgent movements in the early 19th century.[43]

Political instability in Spain, news of rebellions in South America and Miguel Hidalgo's Grito de Dolores prompted small groups to begin fighting against Spanish rule. There were two main groups in Jalisco, one headed by Navarro, Portual and Toribio Huirobo in areas such as Jalostotitlán, Arandas, Atotonilco and La Barca and the other headed by José Antonio Torres in Sahuayo, Tizapán el Alto, Atoyac and Zacoalco. Another insurrection occurred in 1812 along Lake Chapala with Mezcala Island as an insurgent fortress. Skirmishes between the indigenous there and royalist forces lasted until 1816, when lacking supplies, the insurgents accepted an amnesty.[43][48] Insurgent sympathies led to economic advantages for the Mexican born criollos over the Spanish born with many Spanish families moving into the city of Guadalajara for safety.[48]

Miguel Hidalgo's army entered Jalisco during the Mexican War of Independence. In 1810, Guadalajara José Antonio Torres defeated the local royalist army and invited Hidalgo and his troops into the city.[44] Hidalgo was heading west from the State of Mexico, pursued by Félix María Calleja and his troops loyal to the Spanish king. Hidalgo entered the city in November 1810. Hidalgo's troops arrested many Spanish, and Hidalgo issued a decree abolishing slavery. Hidalgo was able to recruit soldiers for his army in the city, bringing it up to 80,000 men by the time Calleja arrived in January 1811. The rebels took up positions outside the city at a place called the Puente de Calderón. Royalist forces won this battle, ending the initial phase of the War and forcing Hidalgo to flee north. Hidalgo was captured and executed later that year.[32][48]

The end of Hidalgo did not finish insurgent aspirations. The newspaper Despertador Americano was founded in 1811 in Guadalajara, sympathetic to the insurgent cause.[44] However, no other major battles of the war would be fought in the state.[32]

Independence was won by Agustín de Iturbide's Army of the Three Guarantees, which would make Iturbide Mexico's first emperor, and making Jalisco one of a number of "departments" which answered directly to Mexico City. This act broke Nueva Galicia's tradition of relative independence and provoked support for federalism.[43] In 1821, a proposal for a "Republic of the United States of Anáhuac" circulated in Guadalajara which called for a federation of states to allow for the best political union in Mexico. Much of these principles appeared with the 1824 Constitution which was enacted after Iturbide was dethroned.[49] Under this Constitution, Colima, Aguascalientes and Nayarit were still part of Jalisco. Its first governor was Prisciliano Sánchez.[44] The new state was divided into eight cantons: Autlán, Colotlán, Etzatlán, Guadalajara, La Barca, Lagos, Sayula, and Tepic.[43]

Independence and the new Constitution did not bring political stability to Jalisco or the rest of the country. In the sixty-year period from 1825 to 1885, Jalisco witnessed twenty-seven peasant (primarily indigenous) rebellions. Seventeen of these uprisings occurred within one decade, 1855–64, and the year 1857 witnessed ten separate revolts.[32] In 1852, in perhaps the most ranging of all Comanche raids, they reached Jalisco.[50] Along with the rest of the county, Jalisco's states vacillated between state and department as Liberals (who supported federalism) and Conservatives fought for permanent control of Mexico. The peasant rebellions and other political acts were in favor of the Liberals and against centralize rule from Mexico City. Jalisco and other western states tried to form a coalition in 1834 against the rule of Antonio López de Santa Anna, but the leaders of Guadalajara were forced to resign under threat of violence instigated by Santa Anna sympathizers, keeping the state in line.[32] During the Mexican–American War, Jalisco planned defensive measures along with the states of Mexico, Querétaro, San Luis Potosí, Zacatecas and Aguascalientes. However, although the U.S. Navy came as close as the port of San Blas, the state was not invaded before the war ended.[51]

The national struggles between Liberals and Conservatives continued in the 1850s and 1860s, with Jalisco's government changing eighteen times between 1855 and 1864. While there was support for Federalism, most Liberals were politically aligned against the Church, which enjoyed strong support in the state.[32] During the Reform War, Benito Juárez's Liberal government was forced out of Mexico City, arriving to Guadalajara in 1858. Despite this, Conservatives in power made Jalisco a department under direct rule from Mexico City. Jalisco remained mostly in Conservative hands until 1861.[44] The war was devastating to the state's economy and forcing mass migrations. Of the thirty most important battles of the Reform War, twelve took place in Jalisco territory.[32]

During the French intervention in Mexico, French forces supporting Mexico's second emperor Maximilian I, entered the state in 1865.[44] The emperor was mostly not supported by the people of the state and in the following year, French forces were defeated at the La Coronilla Hacienda in Acatlán by Mexican General Eulogio Parra. This would allow Liberal forces to retake Guadalajara and push French forces out of the state.[32][43] One permanent result of the French occupation was the separation of the San Blas area into a separately administered military district, which would eventually become the state of Nayarit.[44][51]

In the 1870s, more than seventy percent of the population lived in rural areas.[51] By 1878, the state of Jalisco extended over 115,000 km2 (44,400 sq mi) with twelve cantons, thirty department and 118 municipalities, accounting for ten percent of the country's population.[51]

The end of the century would be dominated by the policies of Mexican President Porfirio Díaz. Livestock, which had been a traditional economic pillar of the state, began to decline during this time. The state's agricultural output also declined slightly relative to the rest of the country during the same period. However, Guadalajara was one of the wealthiest cities in Mexico.[52]

Mexican Revolution to present

Opposition to the Díaz regime was not organized in the state with only isolated groups of miners, students and professionals staging strikes and protests. Presidential challenger Francisco I. Madero visited Guadalajara twice, once in 1909 to campaign and the other in 1910 to organize resistance to the Díaz regime.[44] During the Mexican Revolution, most of the rural areas of the state supported Venustiano Carranza, with uprisings in favor of this army in Los Altos, Mascota, Talpa, Cuquío, Tlajomulco, Tala, Acatlán, Etzatlán, Hostotipaquillo, Mazamitla, Autlán, Magdalena, San Andrés and other places. However, these were isolated incidences and did not coalesce into an organized army to confront the federal government.[43] Carranza vied for power in the state with Álvaro Obregón and Francisco Villa during the early part of the war with skirmishes among the various forces, especially between those loyal to Carranza and Villa.[43]

In 1914, Carranza supporter Manuel M. Diéguez was named governor of Jalisco.[43] Diéguez persecuted the clergy, confiscated the property of the rich and imprisoned or executed the supporters of Victoriano Huerta, whose forces he had pushed out of the city. Villa forced Diéguez to flee and released imprisoned clergy, but he too took money from the rich to give to the poor in exchange for their support. However, by April 1915, Carranza's forces were on the rise again, pushing Villa's forces out and reinstating Diéguez as governor.[32][43]

Carranza gained the Mexican presidency in 1915, putting into place various social and economic reforms such as limits on Church political power and redistribution of agricultural lands.[43][53] One major consequence of the Revolution was the 1917 Constitution. This put severe constraints of the Church including the secularization of public education and even forbade worship outside of churches.[32] One other result was the creation of Jalisco's current boundaries.[43]

The new restrictions on the Church by the Constitution were followed by further laws against the practice of religion which were not supported by many in the state. The lower classes split into those loyal to the church and not.[53] In particular were the "Intolerable Acts" enacted by President Plutarco Elías Calles.[32] In 1926, a boycott was organized against these laws. In 1927, thirteen Catholic unions organized by priest Amando de Alba took up arms against the government in an uprising called the Cristero War. In 1928, Cristero leaders formed a rebel government in areas controlled by them, which was mostly in the Los Altos and far northern areas of the state.[32][43] The struggle resulted in ten different governors of the state between 1926 and 1932.[44] At its height, the Cristeros had a force of about 25,000 until the conflict was officially ended in 1929, with sporadic outbreaks of violence continuing until the 1930s. This waning of hostilities was due to the lack of enforcement of the Calles laws, despite remaining on the books.[32]

During this time, the modern University of Guadalajara was founded in 1926, but it was closed in 1933, then reopened in 1939.[44]

More successful was the implementation was economic reforms begun by Carranza in 1915. By 1935, various agricultural lands were redistributed in the form of ejidos and other communal land ownership.[43][44][53]

From the 1950s, the major concern for the state has been economic development. Most of the state's development has been concentrated in its capital of Guadalajara, resulting is economic inequality in the state.[43]

In 1974, a guerilla group kidnapped former governor José Guadalupe Zuno but released him days after.[43]

Ciudad Guzmán, the center of the 1985 earthquake that destroyed parts of Mexico City, received reconstruction aid. Another major earthquake affected the population of Cihuatlán, Jalisco.[43]

On 21 February 2021, the number of infections from the COVID-19 pandemic in Jalisco that began in March 2020 reached 217,852, and 10,031 people had died.[54]

Tourism

The most important tourist areas in the state are Puerto Vallarta, the Guadalajara metro area, the Costalegre and Los Altos de Jalisco Regions, Lake Chapala and the Montaña Region.[42]

The Guadalajara area's attractions are principally in the city itself and Zapopan, Tlaquepaque and Tonalá.[42] Although the area is mostly urban there are also rural zones such as the Bosque La Primavera, El Diente and Ixtepete.[55]

One of the most famous tourism attractions of the state is the "Tequila Express" which runs from Guadalajara to the town of Tequila. This tour includes visits to tequila distilleries which often offer regional food in buffets accompanied by mariachi musicians and regional dancers.[18] The Tequila Valley area is known for the liquor named after it, made from the blue agave plant. This valley is filled with tequila haciendas, archeological sites and modern distillation facilities. The main historical centers are the towns of Tequila, Cocula, Magdalena and Teuchitlán. The aggregate of the agave fields in this area have been named a World Heritage Site by UNESCO.[56]

Puerto Vallarta on Banderas Bay has beaches such as Los Muertos, Conchas Chinas, Las Glorias, Mismaloya, Punta Negra and Playa de Oro with large hotels, bars, restaurants and discothèques.[42] It has a population of about 250,000 and is the sixth largest city in Jalisco. This bay was a haven for pirates in the 16th century, but today it is one of Mexico's favored diving destinations because of the range of marine life and an average water temperature of between 24.4 and 30.3 °C. Expert level diving is practiced at Marieta Islands at the edge of the bay.[22] On land, one major attraction is the city's nightlife.[57] Ecotourism and extreme sports such as bungee jumping and parasailing are available.[22] Jalisco's coast includes other beaches such as Careyes, Melaque and Tamarindo along with world-famous Puerto Vallarta. The north part of the coast is called the Costalegre de Jalisco.[57] The Costalegre area is classified as an ecological tourism corridor with beaches such as Melaque, Barra de Navidad, Tenacatita, Careyes, El Tecuán, Punta Perula, Chamela and El Tamarindo. All of these have five-star hotels along with bars, restaurants and discothèques.[42] Many coast areas offer activities such as scuba, snorkeling, kayaking, and sports fishing. Majahuas is a marine turtle sanctuary in which visitors may liberate newly hatched turtles into the sea. Puerto Vallarta is known for its nightlife along with its beaches.[57]

The popularity of Lake Chapala began with President Porfirio Díaz who chose the area as a getaway in the late 19th century. This made it popular with Mexico's elite and established the Lake's reputation.[52] Lake Chapala tourism started in the 19th century and steadily pick up in the early 20th century.[58] Beginning in the 1950s, due to the pleasant climate and attractive scenery, a substantial colony of retirees, including many from the United States and Canada , has been established along the Lake's shore,[59] particularly in the town of Ajijic, located just west of the city of Chapala. An estimated 30,000 foreign residents live along the shores of Lake Chapala.[60]

Today, Lake Chapala is popular as a weekend getaway for residents of Guadalajara.[18] The Lake is a tourist attraction on which people sail, fish and jet ski. The Lake is surrounded by a number of towns including Chapala, Jocotepec, Ixtlahuacán de los Membrillos, Ocotlán and Tizapán el Alto. The area has been promoting ecotourism with activities such as rock climbing, rappelling, hiking, golf and tennis along with spas/water parks such as those in Chapala, Jamay, La Barca and Jocotepec.[61] The Norte Region is the home of the Wixarika or Huichols although there are significant communities of an ethnicity called the Cora as well. The area is known for its indigenous culture as well as its rugged, isolated terrain. Major communities in the area include Bolaños and Huejúcar. There is also ecotourism in the way of rappelling, rafting and camping.[62]

The Zonas Altos refer to the area's altitude. The area is marked by parish churches with tall towers. Religion is important in this area, with many pilgrimages, festivals, charreds. It is home to one of the most important pilgrimage sites of Mexico, that of the Virgin of San Juan de los Lagos.[63] Religious tourism is a major economic activity, with the town of San Juan de los Lagos completely dependent on serving the nearly seven million who visit each year.[63][64] The area also has old haciendas open to tourism. There is some tequila production as well although most occurs in the Valles Region.[63]

The Montaña or Mountain Region contains mountain chains such as the Sierra de Tapalpa, Sierra del Tigre and the Sierra del Halo. The main communities in this area are Tapalpa and Mazamitla. The area is filled with forests and green valleys and the state promotes ecotourism in the area with activities such as rappelling, mountain biking, parasailing and hiking. The area's gastronomy includes local sweets and dairy products.[65]

The Sierra Region is between the Centro and coastal areas. Mountains chains in this area include the Sierra de Quila and the Sierra de Manatlán.[66]

Culture

"Jalisco is Mexico"

The idiom "Jalisco is Mexico" refers to how many of the things which are typically associated with Mexico have their origins in Jalisco. These include mariachis, rodeos called charreadas and jaripeos, dresses with wide skirts decorated with ribbons, the Mexican Hat Dance, tequila, and the wide-brimmed sombrero hat.[11][32]

Mariachi and other music

Mexico's best known music, mariachi, is still strongly associated with the state within Mexico, although mariachi bands are popular in many parts of the country. It is a myth that the origin of the name comes from the French word for marriage, as the word existed before the French Intervention in Mexico. Its true origin is unknown but one theory states that it has an indigenous origin. Another postulates that it comes from a local pronunciation of a common mariachi song "María ce son". It is thought to have originated from the town of Cocula, and this kind of band, with variations, spread into Sinaloa, Michoacán, Colima, Nayarit and Zacatecas. The music became most developed in and around the city of Guadalajara,[67] which has a Mariachi Festival in September.[18]

Other common folk music in the state is the jarabe and the son. The jarabe is a type of music which began as a type of hymn especially to the Virgin of Guadalupe. During the Mexican War of Independence, this style was adopted by the insurgents for secular music as well. Some example of famous traditional songs in this style include "Los Enanos", "El Gato", "El Palo" and "El Perico". However, the most famous song is the "Jarabe Tapatío". The word jarabe is thought to come from the Arabic word "sharab" which means syrup or something sweet. The musical style has its roots in Andalucia, Spain and was transplanted to Mexico.[42] The jarabe is mostly associated with Jalisco but it is also popular in a number of other western states such as Nayarit, Colima and Guanajuato. Sones are particularly popular in the south of the state. Some traditional ones from Jalisco include El Son de la Madrugada, El Son de las Alanzas, El Son del la Negra and El Son de las Copetonas.[68]

Traditional clothing and dance

The traditional ranch style clothing of Jalisco is an imitation of Spanish dress that the women of the court wore. The original was heavy in expensive lace and ribbons but the Jalisco version focused on multicolored ribbons. The dresses were made from cotton instead of silk and brocades. The popularity of this dress grew during the Mexican Revolution to various parts of the country, as it was worn by a number of famous female soldiers of the time. Today, it is one considered one type of traditional Mexican dress. Today, this dress is mostly worn for dancing to sons and jarabes. The ribbon dress of Jalisco consists of an ample skirt in one of a number of bright colors. The bottom ruffle generally measures up to 35 cm (14 in) wide, onto which are placed ten strips of ribbons about 1.5 cm (0.6 in) wide in colors that contrast with that of the skirt. The blouse is usually of the same color as the skirt with sleeves extending to the elbows and also decorated with ribbons, especially around the collar. This and other type of folk dance is most often worn on special occasions when traditional dance is performed.[68]

Dresses

There are many differences in traditional Mexican costumes based on the states or regions of the country of Mexico. Each state has very a significant way of dancing but most importantly way of dressing. The style of dress for Jalisco goes back to the mid-1800s to the year 1910.[69] The style of dress comes from the 20th century European fashion, focusing on the French.[69] Another name for this dress is an Escaramuza dress.[70] The fabric that is used to make this dress is all cotton, which is actually very cool. In Jalisco, Mexico the dresses used to dance have bright colored fabric and ribbons. The dress has a wide skirt due to the movements that lift the skirt while dancing. The dress has ruffle at the top of the dress and the throughout the skirt, for a great visual touch. It has a very high neckline with long sleeves. For other touches of details the dress has embroidering details on the skirt, neckline, and top area of the dress. To go along with the dress there are some other accessories that help make the outfit. One of those accessories is the hairstyle, the hairstyle is normally two braids with ribbons in the hair. Another thing that contributes to outfit is the makeup, the make is normally bright colors to match the dress. And lastly, a pair of short heels which makes all the noise when dancing which is part of the idea when dancing.

Tequila

Tequila is a hard liquor which comes from a small region of Jalisco and which is made from the blue agave plant. It is the most famous type of mezcal produced in Mexico, and the only mezcal which is produced industrially with strict standards. The tequila industry supports large scale cultivation of the blue agave, with about 200,000 people employed through it directly or indirectly. It is named after a small town northwest of the city of Guadalajara in the center of where it is produced and the native region of the blue agave. The plant was used in pre-Hispanic times to make a ceremonial drink. The Spanish used the sweet heart of the mature plant, called a piña (literally pineapple) to create a fermented and distilled beverage. The first person to have official permission to make and sell the liquor was José Antonio Cuervo in 1758. In 1888, the first license to export was given to the Sauza family. The drink's popularity rose with the introduction of the railroad, facilitating its shipping. It comes in three styles, blanco (unaged), reposado (aged in oak barrels two months up to one year) and añejo which is aged in oak barrels for a minimum of one year and a maximum of three years. There is also extra anejo aged for a minimum of three years.[71] In the year 2000 the National Museum of Tequila, dedicated to the Tequila was inaugurated.

Cuisine

The pre-Hispanic cuisine of the state features: fish from the various lakes, birds including wild turkey often eaten with salsas made from a wide variety of ground or crushed chili peppers. The Spanish introduced European staples of bread, cattle, sheep, goats, pigs, dairy products, rice and various fruits and vegetables. The European settlers quickly adopted local foodstuffs such as chili peppers and tomatoes to create hybrid dishes such as barbacoa and puchero. Accepting corn as a staple, the Spanish created today's enchiladas, quesadillas and gorditas. They also adopted pre-Hispanic tamales, but these were significantly altered with the addition of large quantities of lard.[18] Tonalá is said to be the origin of pozole, and it is claimed that the local Tonaltecas originally prepared it with human flesh as religious rite.[18]

Classic dishes for the area include local versions of pozole, sopitos, menudo, guacamole, cuachala, birria, pollo a la valenciana and tortas ahogadas. Birria is a meat stew made with roasted chili peppers, spices and with either goat, mutton or beef. Tortas ahogadas are pork sandwiches on French rolls which are covered in a tomato and chili pepper sauce.[18] Common street foods include sopes, tacos, enchiladas tapitíos.[18][72] Tapalpa is known for its Borrego al pastor (grilled mutton); Cocul and Ciudad Guzmán are known for birria; the Lake Chapala area is known for a dish called charales and Guadalajara is known for tortas ahogadas.[42] Sweets include alfajor, squash seeds with honey, coconut candies, buñuelos and fruits conserved in syrup. Drinks include tequila, aquamiel, pulque, tejuino and fruit drinks.[72] Raicilla is a drink made along the coast. Tuba is made in Autlán de Navarro. Rompope is made in Sayula and Tapalpa, and tejuino is most common in the center of the state.[42]

Along the coast, seafood is prominent. Some popular seafood preparations include shrimp breaded with coconut, and rollo del mar, which is a fish fillet stuffed with chopped shrimp and octopus, rolled and sometimes wrapped in bacon and covered in either a chili pepper or almond sauce.[18] Puerto Vallarta has become a gourmet dining attraction as the site of the Mexican Gastronomy Fair held each November. It was a fishing village before a tourist destination and the simple grilled fish dish called 'pescado zarandeado' is still popular.[18]

Catholic faith

Jalisco is home to three highly venerated images of the Virgin Mary which were created in the 16th century and referred to as "sisters." These are the images found in San Juan de los Lagos, Zapopan and Talpa, with the first two the best known in Mexico.[73]

The image at San Juan de Los Lagos has made this small town one of the most-visited pilgrimage sites in Mexico, receiving about seven million visitors each year from all parts of the country. While this image is most often referred to by the place name, she is also called by her native name Cihiuapilli, which means "Great Lady." The church housing the image is filled with folk paintings called "ex votos" or "retablos," which are created to petition the Virgin or to offer thanks for favors received. This image of the Virgin Mary dates from the early 16th century and believed to have been brought to San Juan de Los Lagos by missionaries from Michoacán. The first major miracle attributed to the image occurred in 1623 when a child was revived after being accidentally stuck with spears. The first building dedicated to the image was constructed in 1643, but the current one was finished in 1779. In 1904, the pope granted permission to crown the image and the church received official cathedral status in 1972. Pope John Paul II visited the image in 1990.[64]

The Virgin of Zapopan has her own basilica in the city of that name, but the image spends about half the year traveling to the various parishes of Guadalajara proper. According to legend, thunderstorms in the Guadalajara area were so strong that they killed church bell ringers. The origin of the image's yearly travels was a desire to protect these communities from destruction. Today, the Virgin of Zapopan still travels to the cathedral of Guadalajara every year to spend the rainy season there from June through September. While in Guadalajara, the image travels among the various churches there, accompanied by dancers, musicians and other faithful. In early October, the image is returned to the Zapopan basilica with much fanfare as a long procession in which the image is carried by foot.[73]

- Cathedrals of Jalisco

Parroquia de Santiago Apostol, in Tequila

Parroquia de San Antonio, in Tapalpa

Parroquia de Nuestra Señora de la Asuncion, en Lagos de Moreno

Parroquia de San Miguel Arcangel in San Miguel el Alto

Guadalajara Cathedral

Parroquia de San Francisco in Tepatitlán de Morelos

Catedral Basílica de Nuestra Señora de San Juan de los Lagos in San Juan de los Lagos, 2nd most visited religious center in the country

Basilica of Our Lady of Zapopan, in Zapopan

Basilica de Nuestra Señora del Rosario, in Talpa de Allende

Parroquia de Nuestra Señora de Guadalupe, in Puerto Vallarta

Economy

The economy of the state accounts for 6.3% of Mexico's GDP.[16] It is ranked third in socioeconomic indicators behind Nuevo León and the Federal District of Mexico City.[74] The main sectors of the economy are commerce, restaurants and hotels at 26.1%, services at 21.5%, manufacturing (food processing, bottling and tobacco) at 19.4%, transport, storage and communications at 11.8%, financial services and real estate at 11.2%, agriculture, forestry and fishing at 5.5%, and construction at 4.4%.[75] Jalisco earns just under six percent of Mexico foreign earnings from tourism and employment from the various multinational corporations located in the state,[74] exporting more than $5 billion annually to 81 countries and ranks first among the states in agribusiness, computers and the manufacturing of jewelry.[32] Just over 57% of the population of the state is economically active, the sixth highest percentage in Mexico. 96.6% of this population has employment, of which 15.88% are employed in agriculture, livestock, forestry and fishing, 28.96% are in mining, utilities and construction and 54.82% are in commerce and services.[74] Jalisco received US$508.5 million in foreign direct investment in 2010, representing 6.5% of Mexico's total FDI. The manufacturing industry was the most important for the state in 2010, followed by the food and hotel industry.[76]

The economic center of the state is Guadalajara, with parts of the metro area having living standards comparable to that of the first world, however, on its periphery there is still significant poverty.[26] Guadalajara's economy is based on industry, especially electronics and cybernetics, much of which is located just outside the city center. These industries account for about 75% of the state's production of goods. The major employers are industry (in general), commerce and services.[26] Guadalajara drives the state's economic growth, making Jalisco third in construction in the country.[74]

Agriculture mostly developed in the tropical and subtropical areas.[21] Jalisco's agriculture accounts for 8.44% of the country's production according to GDP. It produces twenty percent of the country's corn, twelve percent of its sugar, twenty five percent of its eggs, twenty percent of its pork, seventeen percent of its dairy products and over twelve percent of its honey, domestic fowl and cattle. It is the country's number one producer of seed corn, corn for animal feed, agave for tequila, limes, fresh milk, eggs, pigs and cattle. It ranks second in the production of sugar, watermelons, honey and barley.[74] 5,222,542 hectares are dedicated to forestry, with eighty percent covered in conifers and broad-leafed trees. A number of these forests contains commercially important hardwoods. On the coasts, there is commercial fishing for shrimp, crabs and tilapia.[21]

Mining developed only in Bolaños, El Barqueño in Guachinango, Pihuamo, Talpa de Allede and Comaja de Corona in Lagos de Moreno and still have active mining. There are important deposits of granite, marble, sandstone and obsidian.[21]

Industry mostly concentrated in the Guadalajara metro area, which has large industrial parks such as El Bosque I, El Bosque II, Guadalajara Industrial Tecnológico, Eco Park, Vallarta, Parque de Tecnología en Electrónica, King Wei and Villa Hidalgo.[74] In food processing, it is first in the production of chocolate products, second in bottling, soft drink production, cement, lime and plaster, third in the production of chemical products.[74]

The tequila industry is very important to the state as the drink has the international place-of-origin designation. The tequila-producing area of Jalisco is a tourist attraction, with more than seventeen million visitors each year, with an estimated value of over ten million pesos per year.[22][74] The tequila industry supports large-scale cultivation of the blue agave, with about 200,000 people employed through it directly or indirectly. It is the only mezcal which is produced industrially with strict norms for its production and origin.[71]

Another important sector of the economy is handcrafts, especially ceramics. Jalisco is the leader in Mexico by volume, quality and diversity of the produced exported which total more than 100 million dollars annually.[74] Jalisco accounts for ten percent of all the handcrafts exported from Mexico. The most representative of the state are the ceramics of Tlaquepaque, Tonalá and Tuxpan, but other common items include the huarache sandals of Concepción de Buenos Aires, piteado from Colotlán, majolica pottery from Sayula, blown glass from Tlaquepaque and Tonalá, equipal chairs from Zacoalco de Torres, jorongo blankets from Talpa and the Los Altos Region and baskets from various parts of the state.[42]

Guadalajara's tourism is mostly concentrated in Puerto Vallarta and Guadalajara. The state has the second largest number of hotels and tour agencies in Mexico and the third highest number of hotel rooms. The state ranks second in banking services and third in professional, technical and other specialized services.[74]

Education

The average number of years of schooling for residents 15 and older is 8.8, higher than the national average of 8.6. Only 5.1% have no schooling whatsoever, with about the same percentage being illiterate and 58.1% have finished primary school (educación básica).[77] Less than one percent has vocational training only, 18.5% have finished education media superior and 17.3% have a bachelor's or higher.[77]

Jalisco has a total number of schools of 20,946, with 304 institutions of higher education.[78] The state has 2,989 preschools, 5,903 primary schools, 1,254 middle schools, fifty vocational/technical schools and 271 high schools. Most, especially at the preschool and primary school levels are private followed by state-sponsored schools.[79]

The largest institution of higher education in the state is the University of Guadalajara which offers ninety-nine bachelor's degrees and eighty-two post-graduate degrees.[79] The university has its origins in the colonial period as the Colegio de Santo Tomás founded in 1591 by the Jesuits. When this order was expelled in 1767 the college closed and was reopened in 1791 as the Real y Literaria Universidad de Guadalajara, beginning with majors in medicine and law. During the 19th century, the university was in turmoil because of the struggle between Liberals and Conservatives, changing name between Instituto de Ciencias del Estado and the Universidad de Guadalajara, depending on who was in power. The name was settled to the latter in 1925 under reorganization. In the 1980s, it was reorganized again and expanded.[80]

The second most important college is the Universidad Autónoma de Guadalajara with fifty-two bachelors and thirty-eight post graduate degrees. Other institutions include the Instituto Tecnológico de Estudios Superiores de Occidente (ITESO), Universidad del Valle de Atemajac, Monterrey Institute of Technology and Higher Education, Guadalajara, Universidad Panamericana and Centro Universitario Guadalajara Lamar[79]

Communication

- Empresas Cablevisión, S.A.B. de C.V., owned by Grupo Televisa, S.A.B. (Izzi Telecom)[81]

- Megacable Holdings S.A.B. de C.V. Guadalajara Cable Holdings. (Megacable)[82]

Infrastructure

Media

The state has seventy-nine radio stations of which seventy-three are commercial enterprises; forty-seven are AM and the rest FM. There are twenty-three television stations, three local and the rest belonging to national chains. There are seven[citation needed] major newspapers El Financiero (de Occidente), El Informador, El Mural, El Occidental, Ocho Columnas, Público, Sol de Guadalajara and Siglo 21.[83][84] There are four companies that provide cable and satellite television.[79]

Transport

It is the second most important transportation hub.[74] Most of the roads in the state radiate outwards from Guadalajara. Until relatively recently, reaching the capital meant traveling down and up steep canyons on narrow winding roads in slow traffic filled with trucks. Today, most of these gorges are traversed by long bridges, making travel far easier.[20] The major highways in the state include the Guadalajara-Saltillo, Guadalajara-Nogales, Guadalajara-Tampico, Guadalajara–Barra de Navidad, Guadalajara-Colima, Guadalajara-Mexico City, Guadalajara–Ciudad Juárez, Guadalajara-Aguascalientes, Guadalajara-Tepic, Macrolibramiento Sur de Guadalajara and, Guadalajara-Lagos de Moreno.[79]

The state has a total of 1,180 km (730 mi) of rail line. The main bus station is the Central de Autobuses of Guadalajara which serves state, national and international destinations. Most destinations are in the west of Mexico and Mexico City.[79]

There are two main airports in the state serving commercial airlines. The largest is Guadalajara International Airport, located in the municipality of Tlajomulco de Zuñiga and serving the Guadalajara Metropolitan Area. The second largest is Puerto Vallarta International Airport, serving both Puerto Vallarta and the Bahía de Banderas municipality in the neighboring state of Nayarit. Additionally, the Zapopan Air Force Base, also located in the Guadalajara Metropolitan Area, serves as a military airport and is home to the Mexican Air Force Academy. There are a number of smaller, general aviation airports in other communities across the state, including Francisco Primo de Verdad National Airport in Lagos de Moreno.

Sports

Guadalajara is home to four professional football teams: CD Guadalajara (also known as Chivas), Club Universidad de Guadalajara, Tecos FC and Atlas.

Charreada, the Mexican form of rodeo and closely tied to mariachi music, is popular in Jalisco.[85] The state hosted the XVI Pan American Games in October 2011, the largest sporting event to be held outside of Mexico City with more than forty nations from the Americas participating. The opening ceremonies were held at Estadio Omnilife in Guadalajara, but sporting events were held in various parts of the state including Puerto Vallarta.[22]

Twinning and covenants

- Nuevo León

- Palmdale, California

Shanghai, China (1998)[86]

Shanghai, China (1998)[86]

See also

- Municipalities of Jalisco

- National Action Party Jalisco

- Western Mexico shaft tomb tradition

References

- ↑ "México en cifras". January 2016. https://www.inegi.org.mx/app/areasgeograficas/?ag=14120.

- ↑ "Las Diputaciones Provinciales" (in es). p. 15. http://biblio.juridicas.unam.mx/libros/6/2920/11.pdf.

- ↑ "Senadores por Jalisco LXI Legislatura". Senado de la Republica. http://www.senado.gob.mx/index.php?ver=int&mn=4&sm=4&id=15.

- ↑ "Listado de Diputados por Grupo Parlamentario del Estado de Jalisco". Camara de Diputados. http://sitl.diputados.gob.mx/LXI_leg/listado_diputados_gpnp.php?tipot=Edo&edot=14.

- ↑ "Resumen". Cuentame INEGI. http://cuentame.inegi.gob.mx/monografias/informacion/jal/default.aspx?tema=me&e=14.

- ↑ "Relieve". Cuentame INEGI. http://cuentame.inegi.gob.mx/monografias/informacion/jal/territorio/relieve.aspx?tema=me&e=14.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 "México en cifras". January 2016. https://www.inegi.org.mx/app/areasgeograficas/#tabMCcollapse-Indicadores.

- ↑ Citibanamex (June 13, 2023). "Indicadores Regionales de Actividad Económica 2023" (in es). https://www.banamex.com/sitios/analisis-financiero/pdf/revistas//IRAE/IRAE2023.pdf.

- ↑ "Jalisco" (US) and "Jalisco". Jalisco. Oxford University Press. http://www.lexico.com/definition/Jalisco.

- ↑ "Jalisco". Merriam-Webster Dictionary. https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/Jalisco. Retrieved 30 May 2019.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 11.3 "Generalidades" (in es). Mexico: State of Jalisco. http://www.jalisco.gob.mx/wps/portal/!ut/p/c5/04_SB8K8xLLM9MSSzPy8xBz9CP0os3ifEB8PY68gIwN_Ex9jAyM3fx9HlyBXAxMfc6B8JE55ICCgOxxkH379IHkDHMDRQN_PIz83Vb8gN8Igy8RREQCX72OH/dl3/d3/L2dJQSEvUUt3QS9ZQnZ3LzZfTFRMSDNKUjIwTzRMMzAyRk9MQURSRTBLMDQ!/.

- ↑ Peddicord, Kathleen. "The 3 Easiest Places To Retire Overseas" (in en). https://www.forbes.com/sites/kathleenpeddicord/2018/10/11/the-3-easiest-places-to-retire-overseas/.

- ↑ Bolotin, Chuck. "What It's Like To Live In Mexico As An Expat During The Coronavirus Shutdown" (in en). https://www.forbes.com/sites/chuckbolotin/2020/04/20/what-its-like-to-live-in-mexico-as-an-expat-during-the-coronavirus-shutdown/.

- ↑ Bolotin, Chuck. "What So Many Americans Find So Appealing About Retiring To Ajijic / Lake Chapala, Mexico" (in en). https://www.forbes.com/sites/chuckbolotin/2019/01/17/what-so-many-americans-find-so-appealing-about-retiring-to-ajijic-lake-chapala-mexico/.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 "Superficie" (in es). INEGI. http://cuentame.inegi.org.mx/monografias/informacion/jal/territorio/default.aspx?tema=me&e=14.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 16.2 16.3 "Resumen" (in es). INEGI. http://cuentame.inegi.org.mx/monografias/informacion/jal/default.aspx?tema=me&e=14.

- ↑ 17.00 17.01 17.02 17.03 17.04 17.05 17.06 17.07 17.08 17.09 17.10 17.11 17.12 17.13 17.14 "Jalisco" (in es). Mexico: State of Jalisco. http://www.jalisco.gob.mx/wps/portal/pj/jalisco/!ut/p/c5/04_SB8K8xLLM9MSSzPy8xBz9CP0os3gzb2djr1AXEwOLYAsLA8_gUAN3Q7NQQ1cDU_1wkA6zeJ8QHw9jryAjA38TH2MDIzd_H0eXIFcDIIDIG-AAjgb6fh75uan6BdnZaY6OiooAzQCPbA!!/dl3/d3/L2dJQSEvUUt3QS9ZQnZ3LzZfTFRMSDNKUjIwTzRMMzAyRk9MQURSRTA0TDc!/.

- ↑ 18.00 18.01 18.02 18.03 18.04 18.05 18.06 18.07 18.08 18.09 18.10 18.11 18.12 Hursh Graber, Karen (June 1, 2007). "The cuisine of Jalisco: la cocina tapatia". Mexconnect. http://www.mexconnect.com/articles/2409-the-cuisine-of-jalisco-la-cocina-tapatia.

- ↑ 19.00 19.01 19.02 19.03 19.04 19.05 19.06 19.07 19.08 19.09 19.10 19.11 19.12 Cuevas Arias, Carmen Teresa; Ofelia Vargas; Aarón Rodríguez (June 2008). "Solanaceae Diversity in the State of Jalisco, Mexico". Revista Mexicana de Biodiversidad (Mexico City: UNAM) 79 (1): 67–79. ISSN 1870-3453. https://www.redalyc.org/pdf/425/42579105.pdf. Retrieved 9 September 2011.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 20.2 20.3 20.4 20.5 20.6 Pint, John (7 November 2010). "The Magic Circle: Mexico's five ecosystems meet around Guadalajara". Mexconnect. http://www.mexconnect.com/articles/3709-the-magic-circle-mexico-s-five-ecosystems-meet-around-guadalajara.

- ↑ 21.00 21.01 21.02 21.03 21.04 21.05 21.06 21.07 21.08 21.09 21.10 21.11 21.12 21.13 21.14 21.15 21.16 21.17 21.18 21.19 "Medio Físico" (in es). Enciclopedia de los Municipios de México Jalisco. Mexico: Instituto Nacional para el Federalismo y el Desarrollo Municipal and Government of Jalisco. 2005. http://www.e-local.gob.mx/work/templates/enciclo/jalisco/medi.htm.

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 22.2 22.3 22.4 22.5 "Jalisco: it's Puerto Vallarta and much more". Association of Canadian Travel Agencies. http://www.acta.ca/?Jalisco.

- ↑ "Hurricane Patricia weakens in Mexico; flood threat remains". 24 October 2015. http://www.cnn.com/2015/10/24/americas/hurricane-patricia/index.html.