John Hancock

From Nwe

From Nwe

| John Hancock | |

|

|

|

First and third governor of Massachusetts

|

|

| In office 1780 – 1785 May 30, 1787 – October 8, 1793 |

|

| Preceded by | Thomas Gage (as governor of the Province of Massachusetts Bay) James Bowdoin (1787) |

|---|---|

| Succeeded by | Thomas Cushing (1785), Samuel Adams (1787) |

|

|

|

| Born | January 12, 1737 Quincy, Massachusetts |

| Died | October 8, 1793 Quincy, Massachusetts |

| Political party | None |

| Spouse | Dorothy Quincy |

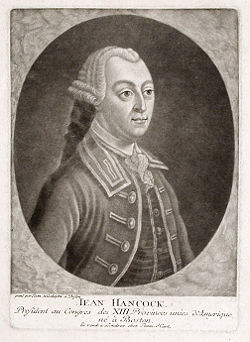

John Hancock (January 12, 1737 – October 8, 1793) was an American leader, politician, writer, political philosopher and one of the Founding Fathers of the United States. Hancock was President of the Second Continental Congress and of the Congress of the Confederation. He served as the first governor of Massachusetts following the secession from England. He was the first person to sign the Declaration of Independence and he played an instrumental role—sometimes by accident, other times by design—in provoking the American Revolutionary War.

Born to privilege and wealth, Hancock used his money to foster the cause for independence from British rule. It was under his leadership as president that the Continental Congress evacuated Philadelphia when the rebellion was in grave danger during 1776 and relocated to the countryside in Newton, Pennsylvania. Throughout his adult life, Hancock gave of himself tirelessly to the cause of human liberty.

Early life

Hancock was born in Braintree, Massachusetts, in a part of town which eventually became the separate city of Quincy, Massachusetts. His father died when he was young, and he was adopted by his paternal uncle Thomas Hancock, a highly successful merchant in New England. After graduating from Boston Latin School, he attended Harvard University and received a business degree in 1754, when he was 17. Upon graduation, he worked for his uncle. From 1760–1764, Hancock lived in England while building relationships with customers and suppliers of his uncle's shipbuilding business. Shortly after his return from England, his uncle died and he inherited the fortune and business, making him the wealthiest man in New England at the time.

Hancock married Dorothy Quincy. Quincy's aunt, also named Dorothy Quincy, was the great-grandmother of Oliver Wendell Holmes, Sr.

The couple had two children, neither of whom survived to adulthood.

Early career

A Boston selectman and representative to the Massachusetts General Court, his colonial trade business naturally disposed him to resist the Stamp Act, which attempted to restrict colonial trading.

The Stamp Act was repealed, but later acts (such as the Townshend Acts) led to further taxation on common goods. Eventually, Hancock's shipping practices became more evasive, and he began to smuggle glass, lead, paper and tea. In 1768, upon arriving from England, his ship Liberty was impounded by British customs officials for violation of revenue laws. This caused a riot among some infuriated Bostonians, depending as they did on the supplies on board.

His regular merchant trade as well as his smuggling practices financed much of his region's resistance to British authority and his financial contributions led the people of Boston to joke that "Sam Adams writes the letters [to newspapers] and John Hancock pays the postage" (Fradin & McCurdy 2002).

American Revolution

At first only a financier of the growing rebellion, he later became a public critic of British rule. On March 5, 1774, the fourth anniversary of the Boston Massacre, he gave a speech strongly condemning the British. In the same year, he was unanimously elected president of the Provisional Congress of Massachusetts, and presided over its Committee of Safety. Under Hancock, Massachusetts was able to raise bands of "minutemen"—soldiers who pledged to be ready for battle in a minute's notice—and his boycott of tea imported by the British East India Company eventually led to the Boston Tea Party.

In April 1775, as the British intent became apparent, Hancock and Samuel Adams slipped away from Boston to elude capture, staying in the Hancock-Clarke House in Lexington, Massachusetts. There, Paul Revere roused them about midnight before the British troops arrived at dawn for the Battle of Lexington and Concord. At this time, General Thomas Gage ordered Hancock and Adams arrested for treason. Following the battle a proclamation was issued granting a general pardon to all who would demonstrate loyalty to the crown—with the exceptions of Hancock and Adams.

On May 24, 1775, he was elected the third president of the Second Continental Congress, succeeding Peyton Randolph. He would serve until October 30, 1777, when he was himself succeeded by Henry Laurens.

In the first month of his presidency, on June 19, 1775, Hancock commissioned George Washington as commander-in-chief of the Continental Army. A year later, Hancock sent Washington a copy of the July 4, 1776 congressional resolution calling for independence as well as a copy of the Declaration of Independence.

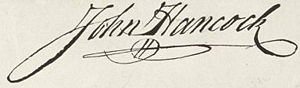

Hancock was the only one to sign the Declaration of Independence on July 4; the other 55 delegates signed on August 2. He also requested Washington have the declaration read to the Continental Army. According to popular legend, he signed his name largely and clearly to be sure King George III could read it without his spectacles, causing his name to become, in the United States, an eponym for "signature."

From 1780–1785, he was governor of Massachusetts. Hancock's skills as orator and moderator were much admired, but during the American Revolution he was most often sought out for his ability to raise funds and supplies for American troops. Despite his skill in the merchant trade, even Hancock had trouble meeting the Continental Congress's demand for beef cattle to feed the hungry army. On January 19, 1781, General Washington warned Hancock:

I should not trouble your Excellency, with such reiterated applications on the score of supplies, if any objects less than the safety of these Posts on this River, and indeed the existence of the Army, were at stake. By the enclosed Extracts of a Letter, of Yesterday, from Major Gen. Heath, you will see our present situation, and future prospects. If therefore the supply of Beef Cattle demanded by the requisitions of Congress from Your State, is not regularly forwarded to the Army, I cannot consider myself as responsible for the maintenance of the Garrisons below West Point, New York, or the continuance of a single Regiment in the Field. (United States Library of Congress, 1781)

Hancock continued to serve as governor of Massachusetts until his death in 1793. He was interred at the Granary Burying Ground in Boston.

References

ISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Fowler, W. M. The Baron of Beacon Hill: A Biography of John Hancock. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1980. ISBN 978-0395276198

- Fradin, Dennis Brindell and Michael McCurdy. The Signers: The 56 Stories Behind the Declaration of Independence. New York: Walker, 2002. ISBN 978-0802788498

- Herrmann, Edward and Roger Mudd. Founding Fathers. New York: A & E Television Networks, 2000. ISBN 978-0767030403

- Somervill, Barbara A. John Hancock: Signer for Independence. Minneapolis, MN: Compass Point Books, 2005. ISBN 978-0756508289

- Unger, Harlow G. John Hancock: Merchant King and American Patriot. New York: John Wiley & Sons, 2000. ISBN 978-0471332091

| Preceded by: James Bowdoin |

Governor of Massachusetts May 30, 1787 – October 8, 1793 |

Succeeded by: Samuel Adams |

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.

↧ Download as ZWI file | Last modified: 02/04/2023 01:19:32 | 2 views

☰ Source: https://www.newworldencyclopedia.org/entry/John_Hancock | License: CC BY-SA 3.0

ZWI signed:

ZWI signed:

KSF

KSF