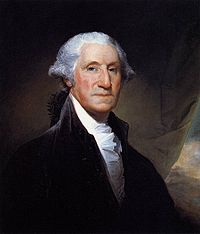

George Washington

From Conservapedia

From Conservapedia | George Washington | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| 1st President of the United States From: April 30, 1789 – March 4, 1797 | |||

| Vice President | John Adams | ||

| Predecessor | None | ||

| Successor | John Adams | ||

| Information | |||

| Party | None[1] | ||

| Spouse(s) | Martha Dandridge Custis Washington | ||

| Religion | Anglican/Episcopalian | ||

| Military Service | |||

| Allegiance | Great Britain, The United States | ||

| Service/branch | Continental Army United States Army | ||

| Service Years | Continental Army: 1775–1783 U. S. Army: 1798–1799 | ||

| Rank | Lieutenant General; General of the Armies of the United States | ||

| Commands | Continental Army United States Army | ||

| Battles/wars | French and Indian War American Revolutionary War | ||

| Awards | Congressional Gold Medal, Thanks of Congress | ||

George Washington (February 22, 1732 – December 14, 1799) was the first president of the United States (1789–1797) and commander-in-chief of the Continental Army. He was the dominant military and political leader of the new United States of America from 1775 to 1797, leading the American victory over Britain in the American Revolution and was the unanimous choice to serve as president.

Along with Abraham Lincoln, Washington has become the foremost icon of American nationalism and a model of the ideal republican union of political and military leadership. He endeared himself to Americans by his efforts to destroy monarchy and aristocracy. The archetype of Washington as the republican champion has become part of America's collective idealization of faith-based citizenship, and is immortalized in New York City's Washington Square Arch, which depicts Washington the soldier on the left, and Washington the statesman on the right.[2]

| “ | The Constitution is the guide, which I never will abandon. — George Washington | ” |

Contents

- 1 Early life

- 2 American Revolution

- 3 Constitution

- 4 First president

- 5 Family and personality

- 6 Christianity

- 7 Freemason

- 8 Parson Weems and the Cherry Tree Story

- 9 Greatness

- 10 Speeches from George Washington

- 11 Quotes from George Washington

- 12 Trivia

- 13 See also

- 14 Bibliography

- 15 Primary sources

- 16 References

- 17 External links

Early life[edit]

Washington was born on February 22, 1732, at Wakefield, Virginia to Augustine Washington, a wealthy planter, and his second wife, Mary Ball. He was home schooled by his father and older half-brother Lawrence, and in later life read widely. His interests were in land, in surveying, and in farming. His father died in 1743, and George lived with Lawrence. Lawrence died in 1752. Washington leased the estate from Lawrence's widow until her death in 1761, when he inherited the plantation and joined the local upper class.

Military experience[edit]

In 1748 he joined an expedition sent out by the sixth Lord Fairfax to survey his lands in the Shenandoah Valley. Washington was eager for a military career. The first step came in October 1753 when the lieutenant governor Robert Dinwiddie sent him to warn the French at Presque Isle (now Erie, PA.) and Fort Le Boeuf (now Waterford, PA) against making further encroachments on British-claimed territory in the Ohio Valley. The 11-week journey, some 500 miles (800 km) round-trip, was dangerous, as Washington evaded hostile Indians (allied to the French). He reported back that a frontier conflict was imminent with France.

French and Indian War[edit]

In April 1754 Washington returned to the Ohio country as a lieutenant colonel in command of a volunteer force with the mission of checking the French and protecting an expedition sent out by the Ohio Company of Virginia to build a fort on the Ohio River, at what is now Pittsburgh. Washington discovered the French had reached the site first. They called it Fort Duquesne. In May he fired on a party of French soldiers, killing ten, including their leader, Jumonville. The French now could cite the attack on Jumonville as a cause of war. This was Washington's first battle and the first engagement of the French and Indian War, which became a major war in Europe.

On July 3 at Fort Necessity he was attacked by superior French forces led by Jumonville's brother and was compelled to surrender. The terms offered were generous and Washington returned to Virginia. Washington was criticized for his imprudence, and relations cooled between him and Dinwiddie.

Battle of Monongahela[edit]

To meet the French threat the British sent Maj. Gen. Edward Braddock and two under-strength regiments of British regulars to Virginia. Washington served as aide-de-camp to Braddock on his expedition to capture Fort Duquesne. Braddock was ambushed and killed by the French and Indians in July, and the Braddock Expedition was a failure.[3] The massacre of the British forces was so complete, that rumors started to make their way around about the death of Washington himself. Washington wrote a letter to his brother, explaining that the rumors were true, and also explaining the miraculous circumstances with which he survived the incident. He wrote:

As I have heard since my arriv'l at this place, a circumstantial acct. of my death and dying speech, I take this early oppertunity of contradicting both, and of assuring you that I now exist and appear in the land of the living by the miraculous care of Providence, that protected me beyond all human expectation; I had 4 Bullets through my Coat, and two Horses shot under me, and yet escaped unhurt.[4]

Years later, Washington returned to the location of the battle. One of the Indian Chiefs, who was also at the battle, was informed that Washington was back in the area. He met with Washington, and he said:

I am a chief and ruler over my tribes. My influence extends to the waters of the great lakes and to the far blue mountains. I have traveled a long and weary path that I might see the young warrior of the great battle. It was on the day when the white man’s blood mixed with the streams of our forests that I first beheld this chief: I called to my young men and said, Mark yon tall and daring warrior? He is not of the red-coat tribe – he hath an Indian's wisdom and his warriors fight as we do – himself alone exposed. Quick, let your aim be certain and he dies. Our rifles were leveled, rifles which, but for you, knew not how to miss – 'twas all in vain, a power mightier far than we shielded you. He can not die in battle. I am old and shall soon be gathered to the great council fire of my fathers in the land of the shades, but ere I go, there is something bids me speak in the voice of prophecy: Listen! The Great Spirit protects that man, and guides his destinies–he will become the chief of nations, and a people yet unborn will hail him as the founder of a mighty empire..[5][6]

Another account by a second Indian warrior, also led him to believe that a greater power was guiding Washington. He said: "Washington was never born to be killed by a bullet! For I had seventeen fair fires at him with my rifle, and after all I could not bring him to the ground."[7][8]

During the battle, Washington displayed courage and initiative in halting the rout that followed, and afterwards became known as the "Hero of Monongahela"[9]

Commander of Virginia Regiment[edit]

In August 1755 he was promoted to colonel and made commander in chief of all Virginia forces, responsible for the defense of a 350-mile (560-km) frontier against French and Indian attack. It was a difficult challenge militarily, but Washington met it and learned the administrative needs of commanding a major force. He was on the defensive throughout 1756 and 1757, but in 1758 he accompanied Brig. Gen. John Forbes and a large force to attack Fort Duquesne. They discovered the French had left and there was no combat. Washington returned to Virginia and resigned his commission at the end of 1758. For him, as for Virginia, the French and Indian War was over. He had been bloodied in combat, was an acknowledged leader of Virginia soldiers, knew the frontier better than anyone, and had a sterling reputation. On the other hand, he had demonstrated no remarkable strategic or tactical skills, and had displayed rashness in action against Jumonville. Washington, a very tall strong man, demonstrated great physical courage and endurance, qualities much admired in a military leader.

Ellis (2004) concludes Washington was influenced by the East, where he picked up the deferential world of British patronage and hierarchy and curried favor from the well-connected Fairfax family, but failed to get a permanent commission in the British army. From the West came experiences on the Ohio frontier, where Washington carried out surveying expeditions and military campaigns against the French and Indians. Going to war instead of to college, Ellis concludes, scarred and immunized Washington against idealism.

Planter and family life[edit]

On Jan. 6, 1759, Washington married Martha Dandridge Custis, a very wealthy widow with two young children. Washington had no children of his own, but he later adopted two of his wife's grandchildren: George Washington Parke Custis and Eleanor Custis, who married Washington's nephew Lawrence. The marriage was a comfortably happy one. It made him rich, for the Custis plantation covered some 17,000 acres and included 300 slaves and a town house in Williamsburg. Washington proved himself an able and active manager, with a keen interest in scientific agriculture and land speculation. He bought up unoccupied western lands shrewdly, even in advance of permission from London. Unlike most planters, he foresaw the risks involved in a concentration on tobacco and diversified his crops. He grew wheat as well as tobacco on his Potomac farms, and by 1772 he was exporting both fish and flour to the West Indies. By 1774 he was one of the wealthiest of landowners at a time when ownership of land involved the administration of managers, overseers, tenants, and slaves; the keeping of accounts with the tobacco factors in Britain; and the ordering from England of most tools, furniture and clothing.

The local gentry controlled local government. Washington became a vestryman (in charge of the local Anglican church) and a justice of the peace. From 1758 to 1765 he was a member of the Virginia House of Burgesses for Frederick County, and from 1765 for Fairfax, although he took little part in affairs in Williamsburg. He was not a debater, speaker or pamphleteer, but nevertheless struck a conspicuous figure as a man of sound military, political and economic judgment. He had shown particular concern over bounty land due to the veterans of the French and Indian War, and he knew the Virginia frontier at first hand. Washington was America's first great entrepreneur, who saw the future of a diversified economy even in the South and achieved it for himself at least; who saw the future of the West and invested in it; and who directed all his activities with a careful and rather cold efficiency.

American Revolution[edit]

Washington's path to revolution reflected the American ideology of republicanism; indeed, it provides "an almost textbook example of the Radical Whig ideology that historians have made the central feature of scholarship on the American Revolution for the past forty years."[10] Personal experiences on multiple levels convinced Washington there was indeed a British conspiracy to enslave the colonies, as he saw imperial policies constantly limiting and restricting his prized autonomy. In his quests for a commission in the redcoat army, for western land, and for economic independence from British consignment merchants, Washington found himself losing out, becoming a helpless dependent.

Washington and the Continental Army triumphed by driving the 10,000 British out of Boston in March 1776. The tide turned; Washington barely survived humiliating defeats the defense of New York City that fall. He revived the nation's fortunes by crossing the Delaware River and defeating British forces in stunning victories at Trenton and Princeton over the winter of 1776–77.

As Ellis (2004) argues, the June 1775-March 1776 siege of Boston was the formative event in Washington's development as a military and political leader, for it was there that he first responded to the logistical problems inherent to the American cause in the Revolutionary War with his trademark determination, leadership ability, and sound decision making. He also, however, exhibited a stubborn, aloof, severe personality that "virtually precluded intimacy." Washington, dubbed "His Excellency" by the adoring American public, also became acquainted with many of his future staff members and lieutenants during this period. The British were forced out of Boston and every place in America, which declared its independence and became "the United States of America" on July 4, 1776.

King George III personally demanded the rebellion be suppressed. He sent two-thirds of his army, and half of the Royal Navy in "the largest projection of seaborne power ever attempted by a European power."[11] The British sent 23,000 regular troops under experienced officers and sergeants, and another 10,000 trained Hessians supported by 70 warships. The ocean off the entire Atlantic coast came under British control, shutting down the large American merchant marine. In the face of this, Washington's forces melted away. He had more than 28,000 men under his command at the end of August when the British landed. After losing badly in New York City, at the beginning of December he had a mere 6,800. But he used them in an audacious Christmas-day attack that destroyed the Hessian garrison at Trenton, New Jersey [12] and defeated the British outpost at Princeton, New Jersey. Threatened by Washington and harassed by patriotic farmer-marksmen, the British withdrew from the state of New Jersey.

In 1777 he tricked the British into dividing their forces so that one British army under General Howe confronted (and defeated) Washington in unimportant battles near Philadelphia, while the main British army under general Cornwallis was forced to surrender at Saratoga, in upstate New York. This great American victory at Saratoga enabling the French to enter the war officially and make it an even contest militarily.

When the British moved in fall 1777 to capture the national capital at Philadelphia, Washington moved south to stop them, but was defeated by Howe at Brandywine (Sept 11) and Germantown (Oct 4). The British wintered in comfort in the city while Washington's army, 11,000 strong at first, had stark quarters at Valley Forge nearby. "The whole of them," said Gen. John Sullivan, were "without watch coats, one half without blankets, and more than one third without shoes . . . many of them without jackets...and not a few without shirts." Rations were scarce, as the local farmers refused to accept Continental money. Exhausted and ill, hundreds deserted to go home to their farms. Washington warned Congress: "unless some great and capital change suddenly takes place... this army must inevitably...starve, dissolve or disperse." Many in Congress grumbled about Washington's leadership and there was talk of promoting his chief critic, General Thomas Conway. However Congress and the army realized Washington was indispensable, and he remained in charge. The bright note was that Washington brought in a highly skilled European officer, General Friedrich von Steuben, who systematically trained the officers and sergeants in the latest drills and maneuvering techniques of the Prussian army.[13]

Victory in the South 1780-1781[edit]

The British made one last major effort in 1780–1781, invading South Carolina (and remote Georgia) in the hopes of rallying enough Loyalists to break off the southern states. Washington kept the main British army bottled up in New York City, as the southern campaigns turned into guerrilla warfare and assassination squads. The British realized they had failed and moved their army to Yorktown, Virginia, awaiting the Royal Navy to take it to New York. The British fleet did show up but was defeated by a stronger French fleet. Washington meanwhile moved his entire army and the French army to Yorktown, where they forced the British to surrender in October 1781.

King George III wanted to fight on even after losing two of his three combat armies but he lost control of Parliament and the American war was over. When the peace treaty was finalized in 1783, Washington triumphantly marched into New York City. Then to the astonishment of the world, Washington—by now the most famous man in the world—stopped the Newburgh Conspiracy, resigned his commission, and went home to his plantation, setting a standard of republican belief in civilian supremacy.

Washington delivered his farewell to his officers on December 4, 1783, at Fraunces Tavern in New York City.[14]

Conflict with the Iroquois[edit]

As part of the revolutionary war, George Washington is said to have massacred the Iroquois. The story goes as follows: On June 4, 1779, Washington ordered the Revolutionary army to invade the land of where the Iroquois tribe was to kill many of them as possible. This widely publicized story states that the invasion had devastated the tribe and their army.[15][16]

The "Ho-De-No-Sau-Nee," or "League of the Iroquois," was a group of five tribes in northern New York and Pennsylvania which joined forces in 1570. As one body represented by 50 members of each tribe, they made decisions relating to trade and war. Day-to-day operations within tribes were left to the jurisdiction of their respective tribes, but matters of war had to be agreed upon by the group. In general, they seemed to side with the British in most matters. However, they also proved deceitful in certain matters, such as the sale of land which did not belong to them, but rather the Shawnee, Delaware and Cherokee.[17] They also generally fought with the British against the colonists.[18]

This system worked until about the time of the American revolution. With many Native Americans as involved in the conflict as Europeans, the Iroquois needed to make a decision on who to fight, but could not. In the end, each tribe tried to go its own way, but most fought against the colonists in favor of the British. Even so, Iroquois made themselves enemies of the British in some cases as well.[19] As the Iroquois Indians had been raiding the colonies' northern frontier, Washington finally ordered the "total destruction and devastation" of Iroquois settlements in order to crush their hostile Confederacy.[15][16][19]

Revisionist history tries to portray this final strike against the Iroquois as a cruel, senseless slaughter of innocent Native Americans. It was quite the opposite, being rather a well-deserved retaliatory strike, putting an end to the ongoing aggression of the alliance. It also removed one of the military options of the British.

Constitution[edit]

Long before most of his contemporaries, Washington realized that independence could not be guaranteed without a standing army and that a nation strong enough to defend itself and to control the West could not exist without a central taxing power and a competent executive authority. All of those things, he admitted. ran directly counter to anti-tax, anti-centralizing sentiments that animated the Revolution. But they were necessary nonetheless, Washington insisted throughout the 1780s. Ellis (2004) concludes that Washington, succeeded in reconciling those contradictions and playing the difficult role of a semi-monarchical republican leader because he understood so well the proper use of power and could project "onto the national screen ... the same kind of controlling authority he had orchestrated within his own personality."[20]

In 1785 Washington hosted the Mount Vernon Conference at his home, which led to both the Annapolis Convention and the creation of the Constitution.

Because of the reputation he gained in the American Revolution, Washington was a logical choice for Virginia to send as a delegate to the Constitutional Convention. There, he was quickly chosen to chair the convention. While he barely ever spoke, the delegates have been said to have designed the Presidency assuming he would be the first President. Other members of the Virginia delegation to the convention were John Blair, James Madison, George Mason, James McClurg, Edmund Randolph, and George Wythe.

First president[edit]

In the first Presidential election, George Washington was enthusiastically and unanimously elected. Reluctantly, he once more assented to the call of duty. This allowed him great freedom in setting up the customs, honors and daily functioning of the new government. Washington surrounded himself with a sophisticated and intelligent group of consultants and supporters and successfully delegated most of the responsibility for the conduct of their offices to those trusted colleagues. He practiced "leading by listening".[21]

One of Washington's greatest achievements was creating the form and style of the new government—a creation that has lasted to this day. The Constitution was vague about administrative details, and under the Confederation the national government was ineffective. Washington created a strong cabinet, with departments of State (foreign affairs), Treasury, War (military and naval affairs), along with an Attorney General. His style was formal but avoided the elaborate ceremonies and costumes of European courts. Washington consulted with his cabinet, but made the decisions himself. He served as his own chief of staff and kept a very small presidential staff in New York City (which was the national capital until it moved to Philadelphia in 1790). He ignored vice president John Adams.

As president Washington employed careful restraint in exercising executive power (to prevent a backlash against centralization), and practiced calculated postponement of potentially lethal issues such as foreign war or ending slavery. His was restrained regarding such issues as the power of the Supreme Court and the abolition of slavery (he quietly favored gradual emancipation), and his absence from early pronouncements in favor of Hamilton's financial plans, allowed him to develop both a nation and an office that appeared above the day-to-day political battles. However, he played a leading role in the struggle to locate the permanent national capital in the District of Columbia and in making military and foreign policy. He believed America's future interests did not depend on Europe but on the people and lands to the nation's west. Washington's vision led to a restrained but effective use of the power of the executive office and the foundations for a strong national government.[22]

Hamiltonian policies[edit]

By far the most important innovations came from Treasury Secretary Alexander Hamilton. Washington gave strong support to Hamilton's successful programs, all approved by Congress, to take over the state debts, to fund the new national debt through a tariff on imports, and to create a national bank, the first Bank of the United States. Thomas Jefferson, the Secretary of State, opposed all these programs but was defeated. Hamilton set up a national network of supporters that became the Federalist Party. Washington never joined the party, but he supported most of its policies and became its iconic symbol. Jefferson and Madison set up a rival party called the Jeffersonian Republicans. Both parties set up newspapers that engaged in nasty invective. By his second term, Washington had become the target of intense attacks from the Republicans. They first portrayed him as an unwitting tool of Hamilton, but later realized that he actually did support Federalist policies.[23]

Whiskey Rebellion, 1794[edit]

Washington decided on decisive action to suppress the Whiskey Rebellion, in which angry farmers in western Pennsylvania were protesting the new federal tax on whiskey. He called on governors to supply militia units, which they did. Washington rode at the head of a strong army into Pennsylvania and the rebellion collapsed without a confrontation.

French Revolution[edit]

Washington had not traveled outside the U.S. (apart from a brief visit to Bermuda), and paid little attention to European affairs. When the French Revolution led to war in 1793 between Britain (America's leading trading partner), and France (the old ally, with a treaty still in effect), Washington and his cabinet decided on a policy of neutrality. Washington supported the Jay's Treaty, designed by Hamilton to avoid war with Britain and encourage commerce. The Jeffersonians vehemently opposed the treaty, but Washington's support proved decisive, and the U.S. and Britain were on friendly terms for a decade.

Farewell Address[edit]

Washington reluctantly served a second term, beginning in 1793, but by 1796 he was exhausted and insisted on not running again. (Since then, no President except Theodore Roosevelt and Franklin Roosevelt has ever tried for a third term; the Twenty-Second Amendment makes this two-term limit into law.) His Farewell Address, partly drafted by Hamilton and Jefferson, remains a classic statement of republicanism, calling on Americans to practice civic virtue and avoid alliances with the warring parties in Europe.

Retirement and death: 1797-99[edit]

Washington returned to his beloved Mount Vernon, but his health continued to decline. In 1798 he accepted appointment as nominal head of a new national army designed to fight the French in a threatened war. (President John Adams chose him as the one man who would command respect from all factions.) His role was nominal, as Hamilton was in effective command.

Washington died in 1799 from acute epiglottitis during an influenza epidemic, and complications from extensive bloodletting.[24] Attending physicians, including his personal physician James Craik, could not agree whether his condition was cynanche, an inflammation of the throat that was believed to require powerful remedies, or something that would require less radical therapeutic interventions than those his physicians had prescribed.[25] Tobias Lear, Washington's personal secretary, reported that his last words were "Tis well."[26]

Family and personality[edit]

Although he had no children, Washington enjoyed a happy family life and especially enjoyed management of his tobacco plantation.

As Henriques (2006) stresses, Washington was driven by a lifelong quest for fame. He zealously guarded his reputation and took great care to ensure that he always acted properly and that he received due acknowledgment for his propriety. Washington prided himself on his honorable actions and was inordinately sensitive to criticism. Ellis (2004) stresses that Washington learned to discipline his emotions as an essential survival skill while facing dangers as a young officer in the Seven Years' War. That capacity for self-control, outwardly manifested in his famous aloofness, served Washington well again during the Revolution, not only by insulating him from criticism, but also by enabling him to curb his ambitions sufficiently to give up power at the end of the war. This earned him the universally honorable reputation that he so ardently desired. Washington was compared, in his willing surrender of power to the Roman leader Cincinnatus, a comparison which drew worldwide attention and acclaim, even in Britain, the nation defeated under his leadership.[27]

Slavery[edit]

Critics argue that Washington's status as a slaveholder, his treatment of his slaves, and his condoning of the institution of slavery besmirch his reputation as the "father of our country." Washington's stay at the President's House in Philadelphia was similarly colored by slavery - nine slaves resided both in the house and in adjacent slave quarters. As a slaveholder, Washington personally struggled to balance the moral injustice of the institution with harsh realities, such as the fact that his own slaves were intermarried with those of his wife, whom he could not legally free. In his will, Washington emancipated his 123 slaves and provided financial support for the elderly and vocational training for the young. He acted in part to remove the only stain on his carefully cultivated reputation.

Christianity[edit]

Washington was a practicing Christian who frequently attended services of several denominations and took seriously his responsibilities as vestryman of his Anglican parish. Washington frequently invoked God and commanded that chaplains be included in every regiment:

"The General hopes and trusts, that every officer and man, will endeavor so to live, and act, as becomes a Christian Soldier, defending the dearest Rights and Liberties of his country."[28]

During one harsh winter while encamped at Valley Forge, an eyewitness reported seeing General Washington pray for God's aid to win the upcoming battles against the British. He said:

"I was riding with Mr. Potts near to the Valley Forge where the army lay during the war of ye Revolution, when Mr. Potts said, 'Do you see that woods & that plain? There laid the army of Washington. It was a most distressing time of ye war, and all were for giving up the Ship but that great and good man. In that woods (pointing to a close in view) I heard a plaintive sound as of a man at prayer.... To my astonishment I saw the great George Washington on his knees alone, with his sword on one side and his cocked hat on the other. He was at Prayer to the God of the Armies, beseeching to interpose with his Divine aid, as it was ye Crisis & the cause of the country, of humanity & of the world. Such a prayer I never heard from the lips of man. ".[29]

Washington declared in his Inaugural Address:

"It would be peculiarly improper to omit, in this first official act, my fervent supplications to that Almighty Being who rules over the Universe. No people can be bound to acknowledge and adore the Invisible Hand which conducts the affairs of men more than the people of the United States. Every step by which they have advanced to the character of an independent nation seems to have been distinguished by some token of Providential agency."[30]Comments such as this one have led some modern historians to conclude that Washington was more a deist than a Christian. Washington told a delegation of Indians:

"You do well to wish to learn our arts and way of life, and above all, the religion of Jesus Christ... Congress will do everything they can to assist you in this wise intention.[31]Washington declared in his Farewell Address:

"Of all the dispositions and habits which lead to political prosperity, religion and morality are indispensable supports." [32]

He began his last will and testament, "In the name of God, Amen".

Washington cherished his Bible so much that he includes the following sentence in his will "To the Reverend, now Bryan, Lord Fairfax, I give a Bible in three large folio volumes, with notes, presented to me by the Right Reverend Thomas Wilson" [33]

Freemason[edit]

On November 4, 1752, Washington was initiated into Freemasonry at Fredricksburg Lodge, Fredricksburg, Virginia. He was passed and raised at the same lodge, becoming a Master Mason on August 4, 1753. He later served as Worshipful Master of Alexandria Lodge No. 22 in Alexandria, Virginia. Upon his death in 1799, he was given a Masonic funeral at his wife's request.[34] Despite this, Washington despised the Illuminati and the Jacobins, which were closely associated with Freemasons and radicalism.[35]

Parson Weems and the Cherry Tree Story[edit]

In 1809, Mason Locke Weems (1756-1825), usually referred to as "Parson Weems," published a book entitled History of the Life and Death, Virtues and Exploits of General George Washington. This book contained many fanciful stories and half-truths, intended to present Washington as a larger-than-life figure. Perhaps the most famous passage in it is Weems' recounting of a story which he attributed to an unnamed "aged lady, who was a distant relative [of Washington], and, when a girl, spent much of her time in the [Washington] family:"

- "When George," said she, "was about six years old, he was made the wealthy master of a hatchet of which, like most little boys, he was immoderately fond, and was constantly going about chopping everything that came in his way. One day, in the garden, where he often amused himself hacking his mother's pea-sticks, he unluckily tried the edge of his hatchet on the body of a beautiful young English cherry-tree, which he barked so terribly, that I don't believe the tree ever got the better of it. The next morning the old gentleman, finding out what had befallen his tree, which, by the by, was a great favorite, came into the house; and with much warmth asked for the mischievous author, declaring at the same time, that he would not have taken five guineas for his tree. Nobody could tell him anything about it. Presently George and his hatchet made their appearance. "George," said his father," do you know who killed that beautiful little cherry tree yonder in the garden?" This was a tough question; and George staggered under it for a moment; but quickly recovered himself: and looking at his father, with the sweet face of youth brightened with the inexpressible charm of all-conquering truth, he bravely cried out, "I can't tell a lie, Pa; you know I can't tell a lie. I did cut it with my hatchet."—"Run to my arms, you dearest boy," cried his father in transports, "run to my arms; glad am I, George, that you killed my tree; for you have paid me for it a thousand fold. Such an act of heroism in my son is more worth than a thousand trees, though blossomed with silver, and their fruits of purest gold."[36][37][38]

(Notice that Weems did not represent Washington as calling it "my little hatchet;" that appears to be a "familiar misquotation.")

Greatness[edit]

Surveys of scholars always rank Washington as one of the two or three greatest presidents—with Abraham Lincoln his main competition.

In an October 2000 survey of 132 prominent professors of history, law, and political science, President Washington was grouped in the "Great" group, ranked 1st, with a mean score of 4.92 out of 5.00.[39]

Speeches from George Washington[edit]

- George Washington's First Inaugural Speech

- George Washington's First Annual Message to Congress

- George Washington's Second Inaugural Address

- George Washington's Farewell Address

Quotes from George Washington[edit]

- "I have only been an instrument in the hands of Providence"

- "The freedom of Speech may be taken away, and, dumb and silent we may be led, like sheep, to the Slaughter." (1783)[40]

- "Reason and experience both forbid us to expect that National morality can prevail in exclusion of religious principle." (1796)[41]

- "There is but one straight course, and that is to seek truth and pursue it steadily."[42]

- "There is no such thing as coincidence. God wills the world according to his design." (1773)[43]

- "The propitious smiles of Heaven, can never be expected on a nation that disregards the eternal rules of order and right, which Heaven itself has ordained: And since the preservation of the sacred fire of liberty, and the destiny of the Republican model of Government, are justly considered as deeply, perhaps as finally staked, on the experiment entrusted to the hands of the American people." (1789)[44]

- "But let there be no change by usurpation; for though this, in one instance, may be the instrument of good, it is the customary weapon by which free governments are destroyed." (1796)[45]

- "Mankind, when left to themselves, are unfit for their own government."[46]

- "Government is not reason; it is not eloquence. It is force. And force, like fire, is a dangerous servant and a fearful master."[47]

„Of all the dispositions and habits which lead to political prosperity, Religion and morality are indispensable supports. In vain would that man claim the tribute of Patriotism, who should labour to subvert these great Pillars of human happiness, these firmest props of the duties of Men & citizens. The mere Politican, equally with the pious man ought to respect & to cherish them. A volume could not trace all their connections with private & public felicity. Let it simply be asked where is the security for property, for reputation, for life, if the sense of religious obligation desert the Oaths, which are the instruments of investigation in Courts of Justice? And let us with caution indulge the supposition, that morality can be maintained without religion. Whatever may be conceded to the influence of refined education on minds of peculiar structure--reason & experience both forbid us to expect that National morality can prevail in exclusion of religious principle. 'Tis substantially true, that virtue or morality is a necessary spring of popular government. The rule indeed extends with more or less force to every species of Free Government. Who that is a sincere friend to it, can look with indifference upon attempts to shake the foundation of the fabric.“ The Papers of George Washington, Documents, The Farewell Address, page 20

Trivia[edit]

George Washington did not have wooden teeth, as many tales have asserted. As early as his 20's, Washington had trouble with his teeth.[48] This would lead to several sets of dentures for Washington, made out of several different materials, including ivory and human teeth.

Washington's dentist was Dr. John Greenwood.[48]

He is rumored to have told Thomas Jefferson that a function of the Senate is to "cool off" legislation passed from the House of Representatives, similarly to how a saucer is used to cool off hot tea.[49][50]

Washington was an accomplished dancer. He took dancing lessons in his teenage years and enjoyed practice throughout his life.[51][52]

See also[edit]

- Washington Elm

- Gallery of American Heroes

- George Washington's Circular Address to the States

- George Washington's speech which ended the Newburgh Conspiracy

- Rules of Civility and Decent Behaviour In Company and Conversation

Bibliography[edit]

Interpretations[edit]

- Cunliffe, Marcus. Washington: Man and Monument (1958),

- Ellis, Joseph J. His Excellency: George Washington (2004), by Pulitzer prize winner

- Ellis, Joseph J. "Inventing the Presidency." American Heritage 2004 55(5): 42–48, 50, 52–53. Issn: 0002-8738 Fulltext: online at Ebsco.

- Henriques, Peter R. Realistic Visionary: A Portrait of George Washington. (2006).

- Higginbotham, Don. George Washington: Uniting a Nation (2002)

- Higginbotham, Don, ed. George Washington Reconsidered. (2001). 336 pp.

- Wood, Gordon S. "The Greatness of George Washington." Virginia Quarterly Review 1992 68(2): 189–207. Issn: 0042-675x Fulltext: in Ebsco

Biographies[edit]

- Alden, John R. George Washington: A Biography (1984)

- Ferling, John E. The First of Men: A Life of George Washington (1988)

- Flexner, James Thomas. Washington: The Indispensable Man (1974). short version of Flexner, George Washington, 4 vols. (1965–1972). vol 1 online, 1732-1775

- Freeman, Douglas Southall, George Washington, 7 vols. (1948–1957); Pulitzer prize; a one-volume condensed version appeared in 1968 vol 1 online

- Lillback, Peter A., George Washington's Sacred Fire; 2006 [3]

Military[edit]

- Alden, John Richard. A History of the American Revolution (1969).

- Bodle, Wayne. Valley Forge Winter: Civilians and Soldiers in War (2002)

- Buchanan, John. The Road to Valley Forge: How Washington Built the Army That Won the Revolution (2004) 368 pp.. online edition

- Fischer, David Hackett. Washington's Crossing (2004), Pulitzer prize winner; study of 1776-77 online excerpt

- Higginbotham, Don. George Washington and the American Military Tradition (1985);

- Higginbotham, Don. The War of American Independence: Military Attitudes, Policies, and Practice, 1763–1789 (1971). an analytical history of the war

- Lengel, Edward G. General George Washington: A Military Life. (2005). 450 pp

- McCullough, David. 1776. 386 pp.

- Reed, John F. Campaign to Valley Forge: July 1, 1777–December 19, 1777 (1965)

- Royster, Charles. A Revolutionary People at War: The Continental Army and American Character, 1775–1783 (1979)

- Taaffe, Stephen R. The Philadelphia Campaign, 1777–1778 (2003).

- Ward, Christopher. The War of the Revolution, 2 vols., 1952, a good narrative of all the major battles.

- Wrong, George M. Washington and His Comrades in Arms: A Chronicle of the War of Independence (1921) by a Canadian scholar online edition

- West Point Atlas online version; the maps are public domain and not copyrighted

Political[edit]

- Bassett, John Spencer. The Federalist System, 1789–1801 (1906), survey of politics online version,

- Chernow, Ron. Alexander Hamilton. Penguin Books, (2004) (ISBN 1-59420-009-2). detailed biography

- Cronin, Thomas F., ed. Inventing the American Presidency. U. Press of Kansas, 1989. 404 pp.

- Deconde, Alexander. Entangling Alliance: Politics & Diplomacy under George Washington (1958) online edition

- Elkins, Stanley M. and Eric McKitrick. The Age of Federalism. (1994) the leading scholarly history of the 1790s. online edition

- Fishman, Ethan M.; William D. Pederson, Mark J. Rozell, eds. George Washington (2001) essays by scholars

- Flaumenhaft; Harvey. The Effective Republic: Administration and Constitution in the Thought of Alexander Hamilton Duke University Press, 1992

- Grizzard, Frank E., Jr. George Washington: A Biographical Companion. ABC-CLIO, 2002. 436 pp. Comprehensive encyclopedia by leading scholar

- Gregg II, Gary L. and Matthew Spalding, eds. George Washington and the American Political Tradition. ISI (1999), essays by scholars

- Leibiger, Stuart. "Founding Friendship: George Washington, James Madison, and the Creation of the American Republic." U. Press of Virginia, 1999. 284 pp.

- McDonald, Forrest. The Presidency of George Washington. 1988. Intellectual history showing Washington as exemplar of republicanism.

- Miller, John C. The Federalist Era, 1789-1801 (1960), political survey of 1790s.

- Miller, John C. Alexander Hamilton: Portrait in Paradox (1959), full-length scholarly biography; online edition

- Morgan, Philip D. "'To Get Quit of Negroes': George Washington and Slavery. Journal of American Studies 2005 39(3): 403-429. Issn: 0021-8758

- Novak, Michael and Novak, Jana. Washington's God: Religion, Liberty, and the Father of Our Country. 2006. 282 pp. Rejects idea that Washington was a deist; he kept his religion private and was probably a Christian

- Nordham, George W. The Age of Washington: George Washington's Presidency, 1789-1797. (1989).

- Pogue, Dennis J. "George Washington: Slave Master." American History 2004 38(6): 52–61. Issn: 1076-8866 Fulltext: in Ebsco, popular history

- Rozell, Mark J., William D. Pederson, Frank J. Williams. George Washington and the Origins of the American Presidency 2000 online edition

- Riccards, Michael P. A Republic, If You Can Keep It: The Foundations of the American Presidency, 1700-1800. (1987)

- Sharp, James. American Politics in the Early Republic: The New Nation in Crisis. (1995), survey of politics in 1790s

- Smith, Robert W. Keeping the Republic: Ideology and Early American Diplomacy. (2004)

- Spalding, Matthew. "George Washington's Farewell Address." The Wilson Quarterly v20#4 (Autumn 1996) pp: 65+.

- White, Leonard D. The Federalists: A Study in Administrative History (1956), thorough analysis of the mechanics of government in 1790s

- Henry Wiencek. An Imperfect God: George Washington, His Slaves, and the Creation of America, 2003. 404 pp.

Primary sources[edit]

- George Washington. Writings (1997) (Library of America edition) 440 letters and key documents, 1184pp online table of contents

Large editions[edit]

Four major editions of Washington's writings have appeared:[53]

- The Writings of George Washington, edited by Jared Sparks (12 volumes, 1833–37)

- The Writings of George Washington, edited by Worthington Chauncey Ford (14 volumes, 1889–93) online volumes

- The Writings of George Washington from the Original Manuscript Sources, 1745-1799, edited by John C. Fitzpatrick (39 volumes, 1931–44). online at Questia

- The Papers of George Washington, edited by W. W. Abbot, Dorothy Twohig, and others, is ongoing; 48 volumes have been published since 1976, and when complete this edition will be the most comprehensive edition so far. See [4] for details

- Washington, George. The Papers of George Washington Colonial Series Volumes 1-10 (complete)

- Washington, George. The Papers of George Washington Revolutionary War Series Volumes 1-16

- Washington, George. The Papers of George Washington Confederation Series Volumes 1-6 (complete)

- Washington, George. The Papers of George Washington: Presidential Series University Press of Virginia. Latest volume is Vol. 12: January–May 1793. ed by Philander D. Chase, 2005. 708 pp.

- Washington, George. The Papers of George Washington Retirement Series Volumes 1-4 (complete)

- Documents of the American Revolution, 1770-1783 Ed. by K.G. Davies. 21 vols. (Irish Academic University Press, 1972), all the important British documents

References[edit]

- ↑ While Washington leaned towards the Federalist Party and supported most of its policies, he never officially joined it, preferring to stay independent.

- ↑ For photographic images, see http://www.nyc-architecture.com/GV/GV046WashingtonSquareArch.htm

- ↑ Atlantic Politics, Military Strategy and the French and Indian War

- ↑ From George Washington to John Augustine Washington, July 18th, 1755

- ↑ George Washington's Sacred Fire

- ↑ The Guardian, Volume 28, 1877

- ↑ The Life of George Washington; with Curious Anecdotes, Equally Honourable to Himself, and Exemplary to His Young Countrymen.

- ↑ History of the Indian Wars: To which is Prefixed a Short Account of the Discovery of America by Columbus, and of the Landing of Our Forefathers at Plymouth

- ↑ George Washington's First War: His Early Military Adventures

- ↑ Ellis (2004) p. 62

- ↑ Fischer (2004) p. 33

- ↑ Hessians lost 896 captured, 22 killed and 83 seriously wounded. Washington lost two men killed in battle, two more frozen to death, and eight wounded. Fischer (2004) pp. 254-5.

- ↑ Quotes from Freeman 4:570, 568.

- ↑ The Minute Man, Volumes 11-20

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 https://www.usnews.com/news/national/articles/2008/06/27/town-destroyer-versus-the-iroquois-indians

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 http://americanhistory.oxfordre.com/view/10.1093/acrefore/9780199329175.001.0001/acrefore-9780199329175-e-3

- ↑ http://firstpeoplesofcanada.com/fp_treaties/fp_treaties_br1stpplafter1763.html

- ↑ TheIroquoisStory retrieved 9/18/17

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 http://www.let.rug.nl/usa/outlines/history-1994/early-america/colonial-indian-relations.php

- ↑ Ellis 2004 p. 274

- ↑ Ellis (2004) p. 175

- ↑ Ellis, "Inventing the Presidency." American Heritage 2004

- ↑ America Afire: Jefferson, Adams, and the Revolutionary Election of 1800. Bernard A. Weisberger.

- ↑ Blood Work: A Tale of Medicine and Murder in the Scientific Revolution

- ↑ Ben Cohen, Ben. "The Death of George Washington (1732-99) and the History of Cynanche." Journal of Medical Biography 2005 13(4): 225-231. Issn: 0967-7720

- ↑ Tobias Lear Tells the Tale of Washington's Death

- ↑ For Lord Byron's poem on the subject, hailing Washington as "the first, the last, the best, the Cincinnatus of the West," see http://www.theotherpages.org/poems/2001/byron0101.html.

- ↑ http://www.amerisearch.net/index.php?date=2004-02-22&view=View

- ↑ From Diary and Remembrances, by Rev. Nathaniel Randolph Snowden (1770-1851), who received it from an eyewitness to the scene, Valley Forge resident Isaac Potts

- ↑ Id.

- ↑ Original Intent, David Barton, 2004, Pg. 168

- ↑ Reading of Washington's Farewell Address -- (Senate - February 22, 2000)

- ↑ Last Will and Testament Ashbrook Center

- ↑ http://freemasonry.bcy.ca/biography/washington_g/washington_g.html

- ↑ Philipp, Joshua (May 29, 2019). Washington’s Warnings Against Partisanship Related to the ‘Illuminati’ and ‘Democratic Socities’. The Epoch Times. Retrieved May 29, 2019.

- ↑ British spellings are as they appear in the original text.

- ↑ Weems, George Mason (1918), History of the Life and Death, Virtues and Exploits of General George Washington. Chapter 2: Birth and Education, online at University of Virginia

- ↑ The Life of George Washington with Curious Anecdotes Equally Honorable to Himself, and Exemplary to his Young Countrymen. 1837, facsimile page images at Google Books

- ↑ Presidential Leadership: Rating the Best and the Worst in the White House (New York, Wall Street Journal Book, 2004)

- ↑ To THE OFFICERS OF THE ARMY, Head Quarters, Newburgh, March 15, 1783, from The writings of George Washington from the original manuscript sources, ed. John C. Fitzpatrick, (Washington: U.S. GPO, 1931-1944)26: 224

- ↑ ("FAREWELL ADDRESS" in Writings, 35:229.

- ↑ To the Secretary of State, in Writings,34:266.

- ↑ From The Diaries of George Washington, 1773)

- ↑ [1]First Inaugural Address

- ↑ Farewell Address; September 19, 1796

- ↑ To Henry Lee, Oct. 31, 1786 online p 202-3

- ↑ The War on Reason

- ↑ 48.0 48.1 False Teeth

- ↑ United States Senate

- ↑ Senatorial Saucer

- ↑ Dancing with General Washington

- ↑ George Washington's Leadership Lessons: What the Father of Our Country Can Teach Us About Effective Leadership and Character

- ↑ See [2] for details

External links[edit]

- White House biography

- Papers of George Washington at the University of Virginia

- Last will and testament

- The Life of George Washington, by David Ramsay

- The Life of George Washington, by Mason Locke Weems

- White House biography

- PBS biography

- Smithsonian Institute biography

- George Washington's Mount Vernon Estate

- Internet Public Library, list of links

- USS George Washington CVN-73

- WASHINGTON MONUMENT the 125th anniversary of the monument's completion and dedication.

- Works by George Washington - text and free audio - LibriVox

- George Washington, by Calista McCabe Courtenay - Audiobook at LibriVox

- George Washington, by Ferdinand Schmidt - Audiobook at LibriVox

| |||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||

Categories: [American Revolutionary War Commanders] [Presidents of the United States] [Founding Fathers] [George Washington] [British History] [American Revolution] [Republicanism] [Conservatives] [Early National U.S.] [Virginia] [Featured articles] [Veterans] [Libertarians] [Pro Second Amendment] [American Gun Rights Advocates] [Patriots]

↧ Download as ZWI file | Last modified: 02/18/2023 16:21:53 | 65 views

☰ Source: https://www.conservapedia.com/George_Washington | License: CC BY-SA 3.0

ZWI signed:

ZWI signed:

KSF

KSF