Anti-Semitism

From Nwe

From Nwe

Anti-Semitism (alternatively spelled antisemitism) is hostility toward or prejudice against Jews as a religious, ethnic, or racial group, which can range from individual hatred to institutionalized, violent persecution. Anti-Semitism has a long history, extending back to the Greco-Roman world and culminating in the Nazi Holocaust. Before the nineteenth century, most anti-Semitism was religiously motivated. Judaism was the only large religious minority after Christianity became the official religion of Europe and so suffered from discriminatory legislation, persecution and violence. Religious anti-Semitism (sometimes called anti-Judaism) usually did not affect those of Jewish ancestry who had converted to another religion—the Spanish Inquisition being the notable exception.

The dominant form of anti-Semitism from the nineteenth century until today has been racial anti-Semitism. With its origins in the cultural anthropological ideas of race that started during the Enlightenment, racial anti-Semitism focused on Jews as a racially distinct group, regardless of their religious practice, viewing them as sub-human and worthy of animosity. With the rise of racial anti-Semitism, conspiracy theories about Jewish plots in which Jews were acting in concert to dominate the world became a popular form of anti-Semitic expression. The highly explicit ideology of Adolf Hitler's Nazism was the most extreme example of this phenomenon, leading to the genocide of European Jewry called the Holocaust.

In Islamic countries, until recently, Jews were generally treated much better than they were in Christian Europe. Muslim attitudes to Jews changed dramatically after the establishment of the State of Israel. It is in the Islamic world that one today finds the most rabid examples of anti-Semitism. Often it masquerades as legitimate criticism of Zionism and Israel's policies, but goes beyond this to attack the Jews more broadly.

Etymology and usage

The term "anti-semitism" derives from the name of Noah's son Shem and his ancestors who are known as Shemites or Semites. Therefore, "anti-Semitism" technically refers not only to Jews but all Semitic peoples, including the Arabs. Historically, however, the term has predominantly been used in a more precise way to refer to prejudice towards Jews alone, and this has been the only use of this word for more than a century.

German political agitator Wilhelm Marr coined the German word Antisemitismus in his book The Way to Victory of Germanicism over Judaism in 1879. Marr used the term as a pseudo-scientific synonym for Jew-hatred or Judenhass. Marr's book became very popular, and in the same year he founded the "League of Anti-Semites" (Antisemiten-Liga), the first German organization committed specifically to combating the alleged threat to Germany posed by the Jews and advocating their forced removal from the country.

In recent decades some groups have argued that the term should be extended to include prejudice against Arabs, otherwise known as anti-Arabism. However, Bernard Lewis, Professor of Near Eastern Studies Emeritus at Princeton University, points out that until now, "anti-Semitism has never anywhere been concerned with anyone but Jews."[1]

Early anti-Semitism

The earliest account of anti-Semitism is to be found in the Book of Esther (third or fourth century B.C.E.) which tells the story of the attempt by Haman to exterminate all the Jews in the Persian Empire under Xerxes. Although this account may not have been historical, it provides evidence that Jews suffered from outbreaks of anti-Semitism in the Persian Empire. Egyptian prejudices against Jews are found in the writings of the Egyptian priest Manetho in the third century B.C.E. who, reacting against the Biblical account of Exodus, claimed the Jews were a leper colony that had been expelled and then taken over Palestine, a land to which they had no claim.[2]

Clash between Hebraism and Hellenism

Sustained antipathy to the Jewish tradition began in the Hellenisitic era.[3] The cosmopolitan Greeks took offense at the Jews' assertion that the universal God had selected them to be his 'Chosen People'. This is known as the scandal of 'particularism.' The Jews further set themselves apart by the unusual practice of circumcision and refusal to marry non-Jews, whom they regarded as unclean. Their dietary laws prevented them from engaging in normal social intercourse. This apparent unfriendliness provoked hostility and accusations of 'strangeness.'

The Greeks from their perspective saw the Jews as a thorn in the side of their multi-racial and multi-national civilized universe, created by Alexander the Great. Proud of their distinguished literary, artistic and philosophical tradition, they regarded their culture as superior and universal, one which should be promoted everywhere. The Greeks were humanists who believed they should make their own laws, choose their own gods and define their identity through their social relationships. Their sexual mores were very liberal, and they glorified the human body encouraging exercise and games in the nude. Alexander the Great deliberately promoted intermarriage and the adoption of Greek culture by establishing gymnasia, theaters and lyceums throughout his empire. After he died his successors built towns and cities throughout the Near East, promoting and often imposing Hellenism.

Hellenization was generally welcomed by the less developed nations of the Near East, except among the Jews. Jews found their primary source of identity in their covenantal relationship with God, whose laws as revealed to Moses were not open to change by human beings. In obedience to these laws, Jews dressed modestly, had conservative sexual mores, and kept a kosher diet. These laws prevented Jews from integrating, and so were regarded by the Greeks as misanthropic and 'inimical to humanity'.[4]

There were Jewish reformers like Philo of Alexandria who were sympathetic to the spirit of Hellenism. However, their efforts were undermined by Greek measures seen as hostile to Jewish survival, such as the events surrounding the Maccabean revolt in 165 B.C.E. In 175 B.C.E. the Seleucid monarch Antiochus IV Epiphanes came to power. Wanting to speed up the Hellenization of his dominions, he replaced the orthodox high priest of the Temple with Jason, a reformer and Hellenizer, who started to transform Jerusalem into a polis. He built a gymnasium where people would exercise in the nude at the foot of the Temple Mount - an activity very shocking to the semitic mind. Temple funds were diverted to international games and dramas. In 167 B.C.E. a decree abolished the Mosaic Law; circumcision, which the Greeks regarded as defacing the human body, was made illegal, and the Temple was made a place of ecumenical worship with a statue of Zeus. This militant rationalism imposed by the power of the state led to a backlash: the Maccabean revolt which culminated in Jewish independence (this episode is celebrated every year at Hanukkah). Professor Cohn-Sherbok said, "the Seleucids served as a model for future forms of anti-Semitism."[3]

The Romans took over the old empire of Alexander but Greek culture continued to dominate, especially in the East. The Roman Empire was run on a liberal basis—local religions and social institutions were respected. Jews were allowed to practice their religion and were exempted from the requirement of emperor worship expected of others. The anti-Semitism of the Greeks though increasingly changed Roman attitudes and policies.[4] Flaccus, the Roman governor of the city of Alexandria, allowed Greek mobs to erect statues of their deities in Jewish synagogues and then declared the Jews outlaws when they resisted, after which thousands of them were killed.[5] Fables about the Jews—such as worshiping asses and human sacrifices in the Temple—were fabricated and endlessly recycled. Josephus records the anti-Judaism of his time in his defense of Judaism Against Apion—Apion being one such critic.

Eventually the Jews of Palestine staged two great revolts against Roman occupation. But, "it is important to grasp that the apparent Jewish revolt against Rome was at bottom a clash between Jewish and Greek culture."[4] The Romans razed Jerusalem and expelled the Jewish people from Palestine. The surviving Jewish authorities under the leadership of Yohanan ben Zakkai made a political settlement with Rome by pledging that Jews would henceforth forswear political activity, and in return Rome gave legal rights to Jews to practice their religion. Nevertheless, anti-Semitism continued to grow in the Empire especially under Hadrian. The historian Tacitus in his widely read Histories compiled a litany of anti-Jewish slanders.[6]

The New Testament

Jesus was a Jew, and all his disciples and early followers were also Jews. The stories in the gospels are of intra-Jewish encounters, debates, disagreements and conflicts. In the gospels Jesus is presented as a harsh critic of official Judaism, accusing it of 'sinfulness and treachery.' In a prophetic fashion he again and again condemns the Pharisees for their understanding of the Mosaic law:

But woe to you Pharisees! for you tithe mint and rue and every herb, and neglect justice and the love of God; these you ought to have done, without neglecting the others. (Luke 11:42)

For the sake of your tradition you made void the word of God. You hypocrites! Well did Isaiah prophesy of you when he said, "This people honors me with their lips, but their heart is far from me; in vain do they worship me, teaching as doctrines the precepts of men." (Matthew 15:6-9)

Many of Jesus' parables, such as the 'wedding feast' (Matthew 22:1-14), present the Jewish people and leaders as failing and being rejected by God. There is a strong supersessionist theology in parables like the 'tenants in the vineyard' (Matthew 21:33-46) where the Jews are replaced in God's providence.

The Gospels minimize the role of the Romans in the crucifixion of Jesus. Instead his death is blamed on the Jewish leaders and people. Matthew's Gospel describes an infamous scene before the Roman governor Pontius Pilate in which "all the [Jewish] people" clamored for Jesus' death, shouting, "Let his blood be on us and on our children!" (Matt 27:24)

In the Book of Acts, Stephen, a Hellenistic Jew, confronts a Jewish council in Jerusalem just before his execution and indicts the Jews as a consistently rebellious people against God: "You stiff-necked people, uncircumcised in heart and ears, you always resist the Holy Spirit. As your fathers did, so do you. Which of the prophets did not your fathers persecute? And they killed those who announced beforehand the coming of the Righteous One, whom you have now betrayed and murdered." (Acts 7:51-53)

Paul was also a Jew and proud of it. His letters contain passages affirming the continuing place of the Jews in God's providence but also some denigrating and denying it.

For it is written that Abraham had two sons, one by the slave woman and the other by the free woman. His son by the slave woman was born in the ordinary way; but his son by the free woman was born as the result of a promise. These things may be taken figuratively, for the women represent two covenants. One covenant is from Mount Sinai and bears children who are to be slaves: This is Hagar. Now Hagar stands for Mount Sinai in Arabia and corresponds to the present city of Jerusalem, because she is in slavery with her children. But the Jerusalem that is above is free, and she is our mother. Now you, brothers, like Isaac, are children of promise. At that time the son born in the ordinary way persecuted the son born by the power of the Spirit. It is the same now. But what does the Scripture say? "Get rid of the slave woman and her son, for the slave woman's son will never share in the inheritance with the free woman's son." (Galatians 4: 21-26, 28-30)

Paul consistently taught that people could not be saved by following the law of Moses, but only through faith in Christ (Galatians 2:16). However, he was not thereby trying to undercut the basis of Judaism; rather he was pursuing his commission as the apostle to the Gentiles. Paul opposed those Jewish-Christians who would make it a requirement that all Christians must follow Jewish law, for it would be a huge obstacle to his evangelical program. His purpose was to open a wide gate for Gentiles to become Christians, without the superfluous and burdensome requirements to be circumcised, keep a kosher diet, and so on.

These criticisms of Jews and Judaism were all part of debates and arguments between different parties of Jews. For instance, when Jesus argued with the Pharisees over whether it was proper to heal on the Sabbath, his view was congruent with many rabbis of his day, the great Hillel among them, who were of the same opinion. When Paul taught that Gentile Christian believers need not be circumcised, he was extending the existing Jewish norm that regarded non-Jews as righteous before God as long as they followed the nine simple Noachide laws. It is the nature of argument that both sides exaggerate to make their point; thus Paul's presentation of the meaning of the Law was a caricature which did not accurately represent first century Judaism. Still, these were arguments within the family. However, once Christians stopped thinking of themselves in any sense as Jews, these New Testament passages took on a different color, and became indictments against Jews generally.

In fact the image of Jews that Christians have had for the past 2000 years has been that obtained from such passages in the New Testament. This is why Jews and more recently some Christians trace the roots of anti-Semitism to the teaching of the New Testament.[3]

Early Christianity

For much of the first century most Christians were Jews who also attended the synagogue. The Jewish-Christian sect was one of several at that time.[7] The animosity between Christians and Jews began as an argument between the small number of Jews who accepted Jesus as the Messiah and most Jews who denied his Messiahship. The controversy became so heated and divisive that Jews who believed in Jesus were expelled from the synagogues and established their own worship services.

Gentiles who attended the synagogue but had not converted to Judaism due to the rigors of keeping the Mosaic law were probably the most open to joining the Jewish-Christians who offered them full and equal membership of the community.[8] As more and more gentiles joined the church they brought with them traditional Greek anti-Semitic attitudes. Ignorant about the internal life of the Jewish community at the time of Jesus, they read many of the New Testament texts as condemnations of Judaism as such rather than internal quarrels which were commonplace within the Jewish community of the period. Christians of Jewish heritage had to stop practicing Jewish traditions such as circumcision and eating only kosher food or else be accused of the heresy of "Judaizing."

Following the New Testament teaching, the early Church Fathers developed an Adversus Judaeos tradition that flourished from the second to the sixth centuries. It was a vicious and malevolent polemic that can be found in sermons and every type of literature. The main accusation was that the Jews had rejected the Messiah and so God had justly rejected them and as a result they deserved to suffer as punishment. They had rebelled against God and so Christians had replaced them as God's elect, the New Israel prophesied in the scriptures. The Christian apologist Justin Martyr in his Dialog with Trypho the Jew (c. 150 C.E.) stated:

The circumcision according to the flesh, which is from Abraham, was given for a sign; that you may be separated from other nations, and from us; and that you alone may suffer that which you now justly suffer; and that your land may be desolate, and your cities burned with fire; and that strangers may eat your fruit in your presence, and not one of you may go up to Jerusalem…. These things have happened to you in fairness and justice.' (Dialog with Trypho, ch. 16)

The apocryphal Letter of Barnabas (c. 100 C.E.) declares that Jesus had abolished the Law of Moses and states that the Jews were "wretched men [who] set their hope on the building (the Temple), and not on their God who made them." In the second century, some Christians went so far as to declare that the God of the Jews was a different being altogether from the loving Heavenly Father described by Jesus. The popular gnostic preacher Marcion, although eventually rejected as a heretic, developed a strong following for this belief, arguing that the Jewish scriptures be rejected by Christians.

In the fifth century C.E., several of the homilies of the famous "golden-tongued" orator John Chrysostom, Bishop of Antioch, were directed against the Jews.[9]

This contempt for Jews was translated into legislation. Formal restrictions against Jews began as early as 305 C.E., when, in Elvira (now Granada) the first known laws of any church council against Jews appeared. Christian women were forbidden to marry Jews unless the Jew first converted to Catholicism. Christians were forbidden to eat with Jews or to maintain friendly social relations with them.

During the First Council of Nicaea in 325 C.E., the Roman emperor Constantine said, "… Let us then have nothing in common with the detestable Jewish crowd; for we have received from our Saviour a different way."[10] Easter was formally separated from the Passover celebration. In 329, Constantine issued an edict providing for the death penalty for any non-Jew who embraced the Jewish faith, as well as for Jews who encouraged them. On the other hand, Jews were forbidden any retaliation against Jewish converts to Christianity. Constantine also forbade marriages between Jews and Christians and imposed the death penalty upon any Jew who transgressed this law.[11]

In 391 C.E., Emperor Theodosius I banned pagan worship and in effect made Christianity the state religion of the Roman Empire. As paganism disappeared there remained one large well organized, highly religious, well educated and prosperous group that spoilt the desired religious uniformity: the Jews. This put the Jews in a vulnerable situation as Christians sought to exercise their new privileges against them. Saint Ambrose, Bishop of Milan, challenged this same Theodosius for being too supportive of the rights of Jews when Theodosius ordered the rebuilding of a Jewish synagogue at a local bishop's expense after a Christian mob had burned it. Ambrose argued that it was inappropriate for a Christian emperor to protect the Christ-rejecting Jews in this way, saying sarcastically:

You have the guilty man present, you hear his confession. I declare that I set fire to the synagogue, or at least that I ordered those who did it, that there might not be a place where Christ was denied.

Legal discrimination against Jews in the wider Christian Roman Empire was formalized in 438, when the Code of Theodosius II established orthodox Christianity as the only legal religion in the empire. The General Council of Chalcedon in 451 banned intermarriage with Jews throughout Christendom. The Justinian Code a century later stripped Jews of many of their civil rights, and Church councils throughout the sixth and seventh century further enforced anti-Jewish provisions.

In 589 in Catholic Spain, the Third Council of Toledo ordered that children born of marriage between Jews and Catholic be baptized by force. By the Twelfth Council of Toledo (681 C.E.) a policy of forced conversion of all Jews was initiated (Liber Judicum, II.2 as given in Roth).[12] Thousands fled, and thousands of others converted to Roman Catholicism.

Anti-Semitism in the Middle Ages

In the Middle Ages the Catholic Church sometimes encouraged anti-Judaism—in 1215 the Fourth Lateran Council declared that all Jews should wear distinctive clothing. At other times it condemned and tried to prevent popular anti-Judaism—in 1272 Pope Gregory X issued a papal bull stating that the popular accusations against Jews were fabricated and false. However, the popular prejudice was just as violent as much of the racial anti-Semitism of a later era. Jews faced vilification as Christ-killers, suffered serious professional and economic restrictions, were accused of the most heinous crimes against Christians, had their books burned, were forced into ghettos, were required to wear distinctive clothing, were forced to convert, faced expulsions from several nations and were massacred.

Accusations

Deicide. Though not part of official Catholic dogma, many Christians, including members of the clergy, have held the Jewish people collectively responsible for rejecting and killing Jesus (see Deicide). This was the root cause for various other suspicions and accusations described below. Jews were considered arrogant, greedy, and self-righteous in their status as "chosen people." The Talmud's occasional criticism of both Christianity and Jesus himself provoked book burnings and widespread suspicion. Ironically these prejudices led to a vicious cycle of policies that isolated and embittered many Jews and made them appear all the more alien to Christian majorities.

Passion plays. These dramatic stagings of the trial and death of Jesus have historically been used in remembrance of Jesus' death during Lent. They often depicted a racially stereotyped Judas cynically betraying Jesus for money and a crowd of Jews clamoring for Jesus' crucifixion while a Jewish leader assumed eternal collective Jewish guilt by declaring "his blood be on our heads!" For centuries, European Jews faced vicious attacks during Lenten celebrations as Christian mobs vented their fury on Jews as "Christ-killers." [13]

Well Poisoning. Some Christians believed that Jews had gained special magical and sexual powers from making a deal with the devil against Christians. As the Black Death epidemics devastated Europe in the mid-fourteenth century, rumors spread that Jews caused it by deliberately poisoning wells. Hundreds of Jewish communities were destroyed by resulting violence. "In one such case, a man named Agimet was … coerced to say that Rabbi Peyret of Chambery (near Geneva) had ordered him to poison the wells in Venice, Toulouse, and elsewhere. In the aftermath of Agimet’s "confession," the Jews of Strasbourg were burned alive on February 14, 1349.[14]

Host Desecration. Jews were also accused of torturing consecrated host wafers in a reenactment of the Crucifixion; this accusation was known as host desecration. Such charges sometimes resulted in serious persecutions (see pictures at right).

Blood Libels. On other occasions, Jews were accused of a blood libel, the supposed drinking of the blood of Christian children in mockery of the Christian Eucharist. The alleged procedure involved a child being tortured and executed in a procedure paralleling the supposed actions of the Jews who did the same to Jesus. Among the known cases of alleged blood libels were:

- The story of young William of Norwich (d. 1144), the first known case of Jewish ritual murder alleged by a Christian monk.

- The case of Little Saint Hugh of Lincoln (d. 1255) which alleged that the boy was murdered by Jews who crucified him.

- The story of Simon of Trent (d. 1475), in which the boy was supposedly held over a large bowl so all his blood could be collected. (Simon was canonized by Pope Sixtus V in 1588. His cult was not officially disbanded until 1965 by Pope Paul VI.)

- In the twentieth century, the Beilis Trial in Russia and the Kielce pogrom in post-Holocaust Poland represented incidents of blood libel in Europe.

- More recently blood libel stories have appeared in the state-sponsored media of a number of Arab nations, in Arab television shows, and on websites.

Demonic. Jews were portrayed as possessing the attributes of the Devil, the personification of evil. They were depicted with horns, tails, the beard of a goat and could be recognized by a noxious smell. "Christian anti-Semitism stemmed largely from the conception of the Jew as the demonic agent of Satan."[3] Despite witnessing Jesus and his miracles and seen the prophecies fulfilled they rejected him. They were accused of knowing the truth of Christianity, because they knew the Old Testament prophecies, but still rejecting it. Thus they appeared to be scarcely human.

Restrictions

Among socio-economic factors were restrictions by the authorities, local rulers, and frequently church officials. Jews were very often forbidden to own land, preventing them from farming. Because of their exclusion from guilds, most skilled trades were also closed to them, pushing them into marginal occupations considered socially inferior, such as tax- and rent-collecting or money lending. Catholic doctrine of the time held that money lending to one's fellow Christian for interest was a sin, and thus Jews tended to dominate this business. This provided the foundation for stereotypical accusations that Jews are greedy and involved in usury. Natural tensions between Jewish creditors and Christian debtors were added to social, political, religious, and economic strains. Peasants, who were often forced to pay their taxes and rents through Jewish agents, could vilify them as the people taking their earnings while remaining loyal to the lords and rulers on whose behalf the Jews worked. The number of Jewish families permitted to reside in various places was limited; they were forcibly concentrated in ghettos; and they were subjected to discriminatory taxes on entering cities or districts other than their own.

The Crusades

The Crusades began as Catholic endeavors to retake Jerusalem from the Muslims and protect the pilgrim routes, but the crusaders were inflamed by a zeal to attack any and all non-believers. Mobs accompanying the first three Crusades, anxious to spill "infidel" blood, attacked Jewish communities in Germany, France and England and put many Jews to death. Entire communities, including those of Treves, Speyer, Worms, Mainz and Cologne, were massacred during the First Crusade by a mob army. The religious zeal fomented by the Crusades at times burned as fiercely against the Jews as against the Muslims, though attempts were made by bishops and the papacy to stop Jews from being attacked. Both economically and socially, the Crusades were disastrous for European Jews.

Expulsions

England. To finance his war to conquer Wales, Edward I of England taxed the Jewish moneylenders. When the Jews could no longer pay, they were accused of disloyalty. Already restricted to a limited number of occupations, the Jews saw Edward abolish their "privilege" to lend money, choke their movements and activities and require them to wear a yellow patch. The heads of many Jewish households were then arrested, over 300 of them taken to the Tower of London and executed, while others were killed in their homes. The complete banishment of all Jews from the country in 1290 led to thousands killed and drowned while fleeing. Jews did not return to England until 1655.

France. The French crown enriched itself at Jewish expense during the twelfth-fourteenth centuries through the practice of expelling the Jews, accompanied by confiscation of their property, followed by temporary readmissions for ransom. The most notable such expulsions were: from Paris by Philip Augustus in 1182, from the entirety of France by Louis IX in 1254, by Charles IV in 1322, by Charles V in 1359, by Charles VI in 1394.

Spain. There had been Jews in Spain possibly since the time of Solomon. They had been relatively secure during Muslim rule of Andalusia. However, the Reconquista (718-1492) took 400 years to re-convert Spain to Catholicism. In Christian Spain however they came under such severe persecution that many converted to Catholicism. Such converts, conversos, were called marranos, a term of abuse derived the prohibition against eating pork (Arabic maḥram, meaning "something forbidden"). Christians suspected that marronos remained secret Jews; and so they continued to persecute them. In 1480 a special Spanish Inquisition was created by the state to search out and destroy conversos who were still practising Judaism and were thus legally heretics. It was under the control of the Dominican prior Torquemada and in less than 12 years condemned about 13,000 conversos. Of the 341,000 victims of the Inquisition. 32,000 were killed by burning, 17,659 were burned in effigy and the remainder suffered lesser punishments. Most of these were of Jewish origin.

In 1492, Ferdinand II of Aragon and Isabella of Castile issued General Edict on the Expulsion of the Jews from Spain and thousands of Spain's substantial Jewish population were force to flee to the Ottoman Empire including the land of Israel/Palestine. There were then about 200,000 Jews in the kingdom but by the end of July 1492 they had all been expelled. They formed the Sephardi Jewish community which was scattered throughout the Mediterranean and Muslim worlds.

Many marranos communities were established all over Europe. They practiced Catholicism for centuries while secretly following Jewish customs. Often they achieved important positions in the economic, social and political realms. But their position was precarious and if discovered they were often put to death.

Germany. In 1744, Frederick II of Prussia limited the city of Breslau (Wrocław in today's Poland) to only ten so-called "protected" Jewish families and encouraged similar practice in other Prussian cities. In 1750 he issued Revidiertes General Privilegium und Reglement vor die Judenschaft: the "protected" Jews had an alternative to "either abstain from marriage or leave Berlin."[15] In the same year, Archduchess of Austria Maria Theresa ordered Jews out of Bohemia but soon reversed her position, on condition that Jews pay for readmission every ten years. In 1752 she introduced a law limiting each Jewish family to one son. In 1782, Joseph II abolished most of persecution practices in his Toleranzpatent, on the condition that Yiddish and Hebrew be eliminated from public records and Jewish judicial autonomy be annulled.

There were also many local expulsions and/or the forced ghettoization of Jews in cities throughout Europe.

The Modern Era

The Reformation and Enlightenment

Although the Reformation was a harbinger of future religious liberty and tolerance in some countries, in the short term it did little to help the majority of European Jews. Martin Luther at first hoped that the Jews would ally with him against Rome and that his preaching of the true Gospel would convert them to Christ. When this did not come to pass he turned his pen against the Jews, writing some of Christianity's most anti-Semitic lines. In On the Jews and their Lies,[16] Luther proposed the permanent oppression and/or expulsion of the Jews. He calls for the burning of synagogues, saying: "First to set fire to their synagogues or schools and to bury and cover with dirt whatever will not burn, so that no man will ever again see a stone or cinder of them." He calls Jews "nothing but thieves and robbers who daily eat no morsel and wear no thread of clothing which they have not stolen and pilfered from us by means of their accursed usury." According to British historian Paul Johnson, Luther's pamphlet "may be termed the first work of modern anti-Semitism, and a giant step forward on the road to the Holocaust."[4]

In his final sermon shortly before his death, however, Luther reversed himself and said: "We want to treat them with Christian love and to pray for them, so that they might become converted and would receive the Lord."[17] Still, Luther's harsh comments about the Jews are seen by many as a continuation of medieval Christian anti-Semitism.

On the positive side, it should be noted that from the Reformation emerged the European and American traditions of tolerance, pluralism, and religious freedom, without which the struggle for the human rights of Jews would certainly have remained futile.

The social currents of the Age of Enlightenment were generally favorable to Jews. In France the Declaration of the Rights of Man and Citizen granted equality to the Jews. Napoleon extended Jewish emancipation throughout much of Europe. From that time, many Jews began to shed their particularistic ways and adopt the norms of European culture. Jews of ability joined the elite of Europe and made numerous contributions to the arts, science and business. Yet anti-Semitism continued nonetheless. The visibility of wealthy Jews in the banking industry led to a resurgence of conspiracy theories about a Jewish plot to take over the world, including the fabrication and publication of the Protocols of the Elders of Zion by the Russian secret police. So this improvement in the status of Jews which enabled them to mix freely in society paradoxically led to modern anti-Semitism: quasi-scientific theories about the racial inferiority of the Jews.

Modern Catholicism

Throughout the nineteenth century and into the twentieth centuries, the Catholic Church still incorporated strong anti-Semitic elements, despite increasing attempts to separate anti-Judaism—the opposition to the Jewish religion on religious grounds—and racial anti-Semitism. Pope Pius VII (1800-1823) had the walls of the Jewish Ghetto in Rome rebuilt after the Jews were released by Napoleon, and Jews were restricted to the Ghetto until the end of the papacy of Pope Pius IX (1846-1878), the last Pope to rule Rome. Pope Pius XII has been criticized for failing to act in defense of the Jews during the Hitler period. Until 1946 the Jesuits banned candidates "who are descended from the Jewish race unless it is clear that their father, grandfather, and great-grandfather have belonged to the Catholic Church."

Since Vatican II, the Catholic Church has taken a stronger stand against anti-Semitism. Paul VI, in Nostra Aetate, declared, "what happened in His passion cannot be charged against all the Jews... then alive, nor against the Jews of today." The Catholic Church, he continued, "decries hatred, persecutions, displays of anti-Semitism, directed against Jews at any time and by anyone." John Paul II went further by confessing that Christianity had done wrong in its previous teachings concerning the Jews, admitting that by "blaming the Jews for the death of Jesus, certain Christian teachings had helped fuel anti-Semitism." He also stated "no theological justification could ever be found for acts of discrimination or persecution against Jews. In fact, such acts must be held as sinful." [18]

Racial anti-Semitism

The advent of racial anti-Semitism was linked to the growing sense of nationalism in many countries. The nationalist dream was of a homogenous nation and Jews were viewed as a separate and often "alien" people who made this impossible. This prejudice was exploited by the politicians of many governments. Nineteenth century comparative anthropology and linguistics had led to the notion of race as the significant cultural unit. The Aryan race was thought to be more ancient (coming from India) and superior in its achievements to the Semitic race. From this point conversion was no longer a solution to the Jewish problem. German society was particularly obsessed with racist doctrines and racist views were articulated by Kant, Hegel, Fichte, Schleiermacher, Bauer, Marx, Treitschke and Richard Wagner as well as a host of lesser known figures from all sections of society. Marx in particular portrayed Jews as exemplars of money grabbing exploitative capitalists. Many anti-Semitic periodicals were published and groups were formed which concerned themselves with issues of racial purity and the contamination of the Aryan blood line by intermarriage with Jews.

As the spirit of religious tolerance spread, racial anti-Semitism gradually superseded anti-Judaism. In the context of the Industrial Revolution, following the emancipation of the Jews from various repressive European laws, impoverished Jews rapidly urbanized and experienced a period of greater social mobility. Jews rapidly rose to prominent positions in academia, science, commerce, the arts, industry and culture. This led to feelings of resentment and envy. For example the greatest poet of the German language, Heinrich Heine (1797-1856) was a Jew and, "his ghostly presence, right at the centre of German literature, drove the Nazis to incoherent rage and childish vandalism".[4] Such success contributed further to myth of Jewish wealth and greed as well as the notion that the Jews were trying to take over the world.

Symptomatic of racial anti-Semitism was the Dreyfus affair, a major political scandal which divided France for many years during the late nineteenth century. It centered on the 1894 treason conviction of Alfred Dreyfus, a Jewish officer in the French army. Dreyfus was, in fact, innocent: the conviction rested on false documents, and when high-ranking officers realized this they attempted to cover up the mistakes. The Dreyfus Affair split France between the Dreyfusards (those supporting Alfred Dreyfus) and the Antidreyfusards (those against him) who in the twentieth century formed an anti-Semitic movement that came to power in the Vichy regime and sent hundreds of thousands of Jews to their death. The venomous anti-Semitism exposed by the affair led Theodor Herzl to conclude that the only solution was for Jews to have their own country. He went on to found the Zionist movement.

Pogroms

Pogroms were a form of race riots, most common in Russia and Eastern Europe, aimed specifically at Jews and often government sponsored. Pogroms became endemic during a large-scale wave of anti-Jewish riots that swept Russia for about thirty years starting in 1881. In some years over 100,000 Jews were expelled or left Russia mostly for the United States. From 1881, thousands of Jewish homes were destroyed, many families reduced to extremes of poverty; women sexually assaulted, and large numbers of men, women, and children killed or injured in 166 Russian towns. The tsar, Alexander III, blamed the Jews for the riots and issued even more restrictions on Jews. Large numbers of pogroms continued until 1884. Bureaucratic measures were taken to regulate and discriminate against Jews.[4] An even bloodier wave of pogroms broke out in 1903-1906, leaving an estimated 2,000 Jews dead and many more wounded. A final large wave of 887 pogroms in Russia and Ukraine occurred during the Russian Revolution of 1917, in which 70,000-250,000 civilian Jews were killed by riots led by various sides.

During the early to mid-1900s, pogroms also occurred in Poland, other East European territories, Argentina, and the Arab world. Extremely deadly pogroms also occurred during World War II beside the Nazi Holocaust itself, including the Romanian Iaşi pogrom in which 14,000 Jews were killed, and the Jedwabne massacre in Poland which killed between 380 and 1,600 Jews. The last mass pogrom in Europe was the post-war Kielce pogrom of 1946.

Anti-Jewish legislation

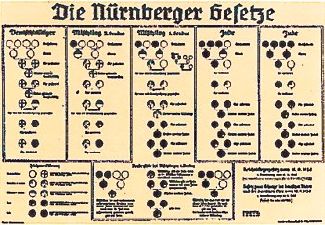

Anti-Semitism was officially adopted by the German Conservative Party at the Tivoli Congress in 1892. Official anti-Semitic legislation was enacted in various countries, especially in Imperial Russia in the nineteenth century and in Nazi Germany and its Central European allies in the 1930s. These laws were passed against Jews as a group, regardless of their religious affiliation; in some cases, such as Nazi Germany, having a Jewish grandparent was enough to qualify someone as Jewish.

In Germany, the Nuremberg Laws of 1935 prevented marriage between any Jew and non-Jew, and made it that all Jews, even quarter- and half-Jews, were no longer citizens of their own country (their official title became "subject of the state"). This meant that they had no basic citizens' rights, e.g., to vote. In 1936, German Jews were banned from all professional jobs, effectively preventing them having any influence in education, politics, higher education and industry. On November 15, 1938, Jewish children were banned from going to normal schools. By April 1939, nearly all Jewish companies had either collapsed under financial pressure and declining profits, or had been persuaded to sell out to the Nazi government. Similar laws existed in Hungary, Romania, and Austria.

The Holocaust

Racial anti-Semitism reached its most horrific manifestation in the Holocaust during World War II, in which about six million European Jews, 1.5 million of them children, were systematically murdered. A virulent anti-Semitism was a central part of Hitler's ideology from the beginning, and hatred of Jews provided both a distraction from other problems and fuel for a totalitarian engine that powered Nazi Germany.

The Nazi anti-Semitic program quickly expanded beyond mere hate speech and the hooliganism of brown-shirt gangs. Starting in 1933, repressive laws were passed against Jews, culminating in the Nuremberg Laws (see above). Sporadic violence against the Jews became widespread with the Kristallnacht riots of November 9, 1938, which targeted Jewish homes, businesses and places of worship, killing hundreds across Germany and Austria.

During the war, Jews were expelled from Germany and sent to concentration camps. Mass murders of Jews occurred in several Eastern European nations as the Nazis took control. The vast majority of Jews killed in the Holocaust were not German Jews, but natives of Eastern Europe. When simply shooting Jews and burying them in mass graves proved inefficient, larger concentration camps were established, complete with gas chambers and crematoria capable of disposing of thousands of human lives per day. Jews and other "inferior" people were rounded up from throughout Nazi-controlled Europe and shipped to the death camps in cattle cars, where a few survived as slave laborers but the majority were put to death.

New anti-Semitism

Following the establishment of the State of Israel in 1948 about 800,000 Jews were expelled or encouraged to leave Muslim countries. Their ancestors had lived in many of these countries for up to 2500 years—since the time of Nebuchadnezzar. Their possessions were seized and they did not receive any compensation. About 600,000 went to Israel and the rest to the United States or Europe. Anti-Semitism in many Muslim countries today repeats all the libels and accusations that were made in Christian Europe.[19] Such matters are propagated in schools, mosques and in the often government-controlled media.

In recent years some scholars of history, psychology, religion, and representatives of Jewish groups, have noted what they describe as the new anti-Semitism, which is associated with the Left, rather than the Right, and which uses the language of anti-Zionism and criticism of Israel to attack the Jews more broadly.[20] Anti-Zionist propaganda in the Middle East frequently adopts the terminology and symbols of the Holocaust to demonize Israel and its leaders. At the same time, Holocaust denial and Holocaust minimization efforts have found increasingly overt acceptance as sanctioned historical discourse in a number of Middle Eastern countries.

Britain's chief rabbi, Sir Jonathan Sacks, has warned that what he called a "tsunami of anti-Semitism" is spreading globally. In an interview with BBC's Radio Four, Sacks said that anti-Semitism was on the rise in Europe. He reported that a number of his rabbinical colleagues had been assaulted, synagogues desecrated, and Jewish schools burned to the ground in France. He also said that: "People are attempting to silence and even ban Jewish societies on campuses on the grounds that Jews must support the state of Israel."[21]

Notes

- ↑ Bernard Lewis, "Semites and Antisemites," Islam in History: Ideas, Men and Events in the Middle East (The Library Press, 1973).

- ↑ Peter Schafer, Judeophobia (Harvard University Press, 1997), 208.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 Dan Cohn-Sherbok, Anti-Semitism: A History (Stroud: Sutton, 2002, ISBN 0750924926).

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 4.5 Paul Johnson, A History of the Jews (London: Weidenfeld & Nicholson, 1987, ISBN 184212479).

- ↑ Pieter Willem Van Der Horst, Philo's Flaccus: the First Pogrom (Philo of Alexandria Commentary Series, Brill, 2003).

- ↑ Tacitus, The Histories 5.2-5.

- ↑ Anne Amos, "The Parting of the Ways" Jewish-Christian Relations. Retrieved April 18, 2018.

- ↑ Klaus Wengst, "When Did Christianity Originate?" Jewish-Christian Relations. Retrieved April 18, 2018.

- ↑ John Chrysostom, "Against the Jews." Homily 1. Retrieved April 18, 2018.

- ↑ Eusebius, "Life of Constantine (Book III)", 337 C.E., Translated by Ernest Cushing Richardson. From Nicene and Post-Nicene Fathers, Second Series, Vol. 1, Edited by Philip Schaff. (Buffalo, NY: Christian Literature Publishing Co., 1890) newadvent.org. Retrieved April 18, 2018.

- ↑ Constantine I. jewishencyclopedia. Retrieved April 18, 2018.

- ↑ Norman Roth, Jews, Visigoths and Muslims in Medieval Spain (Brill Academic, 1994).

- ↑ Charles M. Sennott, "In Poland, new 'Passion' plays on old hatreds", The Boston Globe, April 10, 2004. Retrieved April 18, 2018.

- ↑ Arthur Hertzberg and Aron Hirt-Manheimer, Jews: The Essence and Character of a People (HarperSanFrancisco, 1998, ISBN 0060638346), 84.

- ↑ Simon Dubnow, History of the Jews in Russia and Poland (1918).

- ↑ Anti-Semitism: Martin Luther - "The Jews & Their Lies" (1543) Jewish Virtual Library. Retrieved April 18, 2018.

- ↑ Martin Luther, D. Martin Luther's Werke: kritische Gesamtausgabe (Weimar: Hermann Böhlaus Nachfolger, 1920, Vol. 51), 195.

- ↑ Thomas G. Lederer, Relations between Catholics and Jews before and after Vatican II Retrieved April 18, 2018.

- ↑ Bernard Lewis, "Muslim Anti-Semitism" Middle East Quarterly (June 1998) MiddleEast Forum. Retrieved April 18, 2018.

- ↑ Phyllis Chesler, The New Anti-Semitism: The Current Crisis and What We Must Do About It (Jossey-Bass/Wiley, 2003), 158-159, 181.

- ↑ Audrey Gillan, "Chief rabbi fears 'tsunami' of hatred", Guardian, January 2, 2006. Retrieved April 18, 2018.

References

ISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Bodansky, Yossef. Islamic Anti-Semitism as a Political Instrument. Freeman Center For Strategic Studies, 1999.

- Carr, Steven Alan. Hollywood and anti-Semitism: A cultural history up to World War II. Cambridge University Press, 2001.

- Chesler, Phyllis. The New Anti-Semitism: The Current Crisis and What We Must Do About It. (original 1995) Jossey-Bass/Wiley, 2003. ISBN 078796851X

- Cohn, Norman. Warrant for Genocide. [1967] Serif, 1996.

- Cohn-Sherbok, Dan. Anti-Semitism: A History. Stroud: Sutton, 2002. ISBN 0750924926

- Cohn-Sherbok, Dan. The Crucified Jew: Twenty Centuries of Christian Anti-Semitism. London: 1992. ISBN 0006276040

- Cohn-Sherbok, Dan. Understanding the Holocaust. London: Continuum, 2000. ISBN 0826454526

- Dubnow, Simon. History of the Jews in Russia and Poland.(original 1918). Ktav Pub. House, 1975. ISBN 0870682172

- Evans, Craig A. and Donald A. Hagner, eds. Anti-Semitism and Early Christianity: Issues of Polemic and Faith. Minneapolis: Fortress Press, 1993.

- Freudmann, Lillian C. Antisemitism in the New Testament. University Press of America, 1994.

- Hertzberg, Arthur, and Aron Hirt-Manheimer. Jews: The Essence and Character of a People. HarperSanFrancisco, 1998, ISBN 0060638346.

- Hilberg, Raul. The Destruction of the European Jews, third ed., 3 volumes. original 1961) Yale University Press, 2003. ISBN 0300095570

- Johnson, Paul. A History of the Jews. London: Weidenfeld & Nicholson, 1987. ISBN 184212479

- Lewis, Bernard. "Semites and Antisemites," Islam in History: Ideas, Men and Events in the Middle East, updated second ed. (original 1973) Open Court, 2001. ISBN 0812695186.

- Lipstadt, Deborah. Denying the Holocaust: The Growing Assault on Truth and Memory. Penguin, 1994.

- Prager, Dennis, and Joseph Telushkin. Why the Jews? The Reason for Antisemitism. Touchstone (original 1985) 2003. ISBN 0743246209.

- Roth, Norman. Jews, Visigoths and Muslims in Medieval Spain. Brill Academic, 1994. ISBN 9004099719

- Schafer, Peter. Judeophobia: Attitudes toward the Jews in the Ancient World. Harvard University Press, 1997. ISBN 0674487788

- Selzer, Michael, ed. "Kike!": A documentary history of anti-Semitism in America. World Pub., 1972. ISBN 0529044714

- Van Der Horst, Pieter Willem (Translator). Philo's Flaccus: The First Pogrom. (Philo of Alexandria Commentary Series (Society of Biblical Literature), V. 2.) Society of Biblical Literature, 2005. ISBN 1589831888

External links

All links retrieved October 30, 2021.

- Why the Jews? A perspective on causes of anti-Semitism

- Religion: Anti-Semitism jewishvirguallibrary.org.

- Anti-Defamation League on Anti-Semitism

- Judeophobia: A short course on the history of anti-Semitism at Zionism and Israel Information Center.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.

↧ Download as ZWI file | Last modified: 02/04/2023 05:33:11 | 399 views

☰ Source: https://www.newworldencyclopedia.org/entry/Antisemitism | License: CC BY-SA 3.0

ZWI signed:

ZWI signed:

KSF

KSF