Thermodynamics

From Nwe

From Nwe Thermodynamics (from the Greek θερμη, therme, meaning "heat" and δυναμις, dynamis, meaning "power") is a branch of physics that studies the effects of changes in temperature, pressure, and volume on physical systems at the macroscopic scale by analyzing the collective motion of their particles using statistics.[1] In this context, heat means "energy in transit" and dynamics relates to "movement;" thus, thermodynamics is the study of the movement of energy and how energy instills movement. Historically, thermodynamics developed out of need to increase the efficiency of early steam engines.[2]

The starting point for most thermodynamic considerations are the laws of thermodynamics, which postulate that energy can be exchanged between physical systems as heat or work.[3] The first law of thermodynamics states a universal principle that processes or changes in the real world involve energy, and within a closed system the total amount of that energy does not change, only its form (such as from heat of combustion to mechanical work in an engine) may change. The second law gives a direction to that change by specifying that in any change in any closed system in the real world the degree of order of the system's matter and energy becomes less, or conversely stated, the amount of disorder (entropy) of the system increases.[4]

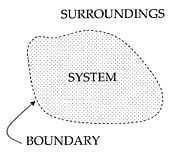

In thermodynamics, interactions between large ensembles of objects are studied and categorized. Central to this are the concepts of system and surroundings. A system comprises particles whose average motions define the system's properties, which are related to one another through equations of state defining the relations between state variables such as temperature, pressure, volume, and entropy. State variables can be combined to express internal energy and thermodynamic potentials, which are useful for determining conditions for equilibrium and spontaneous processes.[5]

With these tools, thermodynamics describes how systems respond to changes in their surroundings. This can be applied to a wide variety of topics in science and engineering, such as engines, phase transitions, chemical reactions, transport phenomena, and even black holes. The results of thermodynamics are essential for other fields of physics and for chemistry, chemical engineering, aerospace engineering, mechanical engineering, cell biology, biomedical engineering, and materials science to name a few.[6]

Thermodynamics, with its insights into the relations between heat, energy, and work as exemplified in mechanical systems, provides a foundation for trying to understand the behavior and properties of biological, social, and economic systems, which generally maintain an ordered pattern only by consuming a sustained flow of energy.

The laws of thermodynamics

In thermodynamics, there are four laws of very general validity, and as such they do not depend on the details of the interactions or the systems being studied. Hence, they can be applied to systems about which one knows nothing other than the balance of energy and matter transfer. Examples of this include Einstein's prediction of spontaneous emission around the turn of the twentieth century and current research into the thermodynamics of black holes.

The four laws are:

- Zeroth law of thermodynamics, stating that thermodynamic equilibrium is an equivalence relation.

-

- If two thermodynamic systems are separately in thermal equilibrium with a third, they are also in thermal equilibrium with each other.

- First law of thermodynamics, about the conservation of energy

-

- The change in the internal energy of a closed thermodynamic system is equal to the sum of the amount of heat energy supplied to the system and the work done on the system.

- Second law of thermodynamics, about entropy

-

- The total entropy of any isolated thermodynamic system tends to increase over time, approaching a maximum value.

- Third law of thermodynamics, about absolute zero temperature

-

- As a system asymptotically approaches absolute zero of temperature all processes virtually cease and the entropy of the system asymptotically approaches a minimum value; also stated as: "The entropy of all systems and of all states of a system is zero at absolute zero" or equivalently "it is impossible to reach the absolute zero of temperature by any finite number of processes."

Thermodynamic systems

An important concept in thermodynamics is the “system.” Everything in the universe except the system is known as surroundings. A system is the region of the universe under study. A system is separated from the remainder of the universe by a boundary which may or may not be imaginary, but which by convention delimits a finite volume. The possible exchanges of work, heat, or matter between the system and the surroundings take place across this boundary. Boundaries are of four types: Fixed, movable, real, and imaginary.

Basically, the “boundary” is simply an imaginary dotted line drawn around the volume of a something in which there is going to be a change in the internal energy of that something. Anything that passes across the boundary that effects a change in the internal energy of that something needs to be accounted for in the energy balance equation. That “something” can be the volumetric region surrounding a single atom resonating energy, such as Max Planck defined in 1900; it can be a body of steam or air in a steam engine, such as Sadi Carnot defined in 1824; it can be the body of a tropical cyclone, such as Kerry Emanuel theorized in 1986, in the field of atmospheric thermodynamics; it could also be just one nuclide (that is, a system of quarks) as some are theorizing presently in quantum thermodynamics.

For an engine, a fixed boundary means the piston is locked at its position; as such, a constant volume process occurs. In that same engine, a movable boundary allows the piston to move in and out. For closed systems, boundaries are real, while for open systems, boundaries are often imaginary. There are five dominant classes of systems:

- Isolated Systems—matter and energy may not cross the boundary

- Adiabatic Systems—heat must not cross the boundary

- Diathermic Systems—heat may cross boundary

- Closed Systems—matter may not cross the boundary

- Open Systems—heat, work, and matter may cross the boundary (often called a control volume in this case)

As time passes in an isolated system, internal differences in the system tend to even out and pressures and temperatures tend to equalize, as do density differences. A system in which all equalizing processes have gone practically to completion is considered to be in a state of thermodynamic equilibrium.

In thermodynamic equilibrium, a system's properties are, by definition, unchanging in time. Systems in equilibrium are much simpler and easier to understand than systems that are not in equilibrium. Often, when analyzing a thermodynamic process, it can be assumed that each intermediate state in the process is at equilibrium. This will also considerably simplify the situation. Thermodynamic processes which develop so slowly as to allow each intermediate step to be an equilibrium state are said to be reversible processes.

Thermodynamic parameters

The central concept of thermodynamics is that of energy, the ability to do work. As stipulated by the first law, the total energy of the system and its surroundings is conserved. It may be transferred into a body by heating, compression, or addition of matter, and extracted from a body either by cooling, expansion, or extraction of matter. For comparison, in mechanics, energy transfer results from a force which causes displacement, the product of the two being the amount of energy transferred. In a similar way, thermodynamic systems can be thought of as transferring energy as the result of a generalized force causing a generalized displacement, with the product of the two being the amount of energy transferred. These thermodynamic force-displacement pairs are known as conjugate variables. The most common conjugate thermodynamic variables are pressure-volume (mechanical parameters), temperature-entropy (thermal parameters), and chemical potential-particle number (material parameters).

Thermodynamic states

When a system is at equilibrium under a given set of conditions, it is said to be in a definite state. The state of the system can be described by a number of intensive variables and extensive variables. The properties of the system can be described by an equation of state which specifies the relationship between these variables. State may be thought of as the instantaneous quantitative description of a system with a set number of variables held constant.

Thermodynamic processes

A thermodynamic process may be defined as the energetic change of a thermodynamic system proceeding from an initial state to a final state. Typically, each thermodynamic process is distinguished from other processes in energetic character, according to what parameters, such as temperature, pressure, or volume, etc., are held fixed. Furthermore, it is useful to group these processes into pairs, in which each variable held constant is one member of a conjugate pair. The seven most common thermodynamic processes are shown below:

- An isobaric process occurs at constant pressure

- An isochoric process, or isometric/isovolumetric process, occurs at constant volume

- An isothermal process occurs at a constant temperature

- An adiabatic process occurs without loss or gain of heat

- An isentropic process (reversible adiabatic process) occurs at a constant entropy

- An isenthalpic process occurs at a constant enthalpy. Also known as a throttling process or wire drawing

- A steady state process occurs without a change in the internal energy of a system

History

A brief history of thermodynamics begins with Otto von Guericke who, in 1650, built and designed the world's first vacuum pump and created the world's first ever vacuum (known as the Magdeburg hemispheres). He was driven to make a vacuum in order to disprove Aristotle's long-held supposition that "nature abhors a vacuum." Shortly thereafter, Irish physicist and chemist Robert Boyle had learned of Guericke's designs and in 1656, in coordination with English scientist Robert Hooke, built an air pump.[7] Using this pump, Boyle and Hooke noticed the pressure-temperature-volume correlation. In time, Boyle's Law was formulated, which states that pressure and volume are inversely proportional. Then, in 1679, based on these concepts, an associate of Boyle's named Denis Papin built a bone digester, which was a closed vessel with a tightly fitting lid that confined steam until a high pressure was generated.

Later designs implemented a steam release valve that kept the machine from exploding. By watching the valve rhythmically move up and down, Papin conceived of the idea of a piston and a cylinder engine. He did not, however, follow through with his design. Nevertheless, in 1697, based on Papin's designs, engineer Thomas Savery built the first engine. Although these early engines were crude and inefficient, they attracted the attention of the leading scientists of the time. One such scientist was Sadi Carnot, the "father of thermodynamics," who in 1824 published Reflections on the Motive Power of Fire, a discourse on heat, power, and engine efficiency. The paper outlined the basic energetic relations between the Carnot engine, the Carnot cycle, and Motive power. This marks the start of thermodynamics as a modern science.

Classical thermodynamics is the original early 1800s variation of thermodynamics concerned with thermodynamic states, and properties as energy, work, and heat, and with the laws of thermodynamics, all lacking an atomic interpretation. In precursory form, classical thermodynamics derives from chemist Robert Boyle’s 1662 postulate that the pressure P of a given quantity of gas varies inversely as its volume V at constant temperature; in equation form: PV = k, a constant. From here, a semblance of a thermo-science began to develop with the construction of the first successful atmospheric steam engines in England by Thomas Savery in 1697 and Thomas Newcomen in 1712. The first and second laws of thermodynamics emerged simultaneously in the 1850s, primarily out of the works of William Rankine, Rudolf Clausius, and William Thomson (Lord Kelvin).[8]

The term "thermodynamics" was coined by James Joule in 1858, to designate the science of relations between heat and power. By 1849, "thermo-dynamics," as a functional term, was used in William Thomson's paper, An Account of Carnot's Theory of the Motive Power of Heat.[9] The first thermodynamic textbook was written in 1859, by William Rankine, originally trained as a physicist and a civil and mechanical engineering professor at the University of Glasgow.[10]

With the development of atomic and molecular theories in the late nineteenth century, thermodynamics was given a molecular interpretation. This "statistical thermodynamics," can be thought of as a bridge between macroscopic and microscopic properties of systems.[11] Essentially, statistical thermodynamics is an approach to thermodynamics situated upon statistical mechanics, which focuses on the derivation of macroscopic results from first principles. It can be opposed to its historical predecessor phenomenological thermodynamics, which gives scientific descriptions of phenomena with avoidance of microscopic details. The statistical approach is to derive all macroscopic properties (temperature, volume, pressure, energy, entropy, and so on) from the properties of moving constituent particles and the interactions between them (including quantum phenomena). It was found to be very successful and, thus, is commonly used.

Chemical thermodynamics is the study of the interrelation of heat with chemical reactions or with a physical change of state within the confines of the laws of thermodynamics. During the years 1873-76, the American mathematical physicist Josiah Willard Gibbs published a series of three papers, the most famous being On the Equilibrium of Heterogeneous Substances, in which he showed how thermodynamic processes could be graphically analyzed, by studying the energy, entropy, volume, temperature, and pressure of the thermodynamic system, in such a manner to determine if a process would occur spontaneously.[12] During the early twentieth century, chemists such as Gilbert N. Lewis, Merle Randall, and E.A. Guggenheim began to apply the mathematical methods of Gibbs to the analysis of chemical processes.[13]

Thermodynamic instruments

There are two types of thermodynamic instruments, the meter and the reservoir.. A thermodynamic meter is any device that measures any parameter of a thermodynamic system. In some cases, the thermodynamic parameter is actually defined in terms of an idealized measuring instrument. For example, the zeroth law states that if two bodies are in thermal equilibrium with a third body, they are also in thermal equilibrium with each other. This principle, as noted by James Maxwell in 1872, asserts that it is possible to measure temperature. An idealized thermometer is a sample of an ideal gas at constant pressure. From the ideal gas law PV=nRT, the volume of such a sample can be used as an indicator of temperature; in this manner it defines temperature. Although pressure is defined mechanically, a pressure-measuring device, called a barometer may also be constructed from a sample of an ideal gas held at a constant temperature. A calorimeter is a device which is used to measure and define the internal energy of a system.

A thermodynamic reservoir is a system which is so large that it does not appreciably alter its state parameters when brought into contact with the test system. It is used to impose a particular value of a state parameter upon the system. For example, a pressure reservoir is a system at a particular pressure, which imposes that pressure upon any test system that it is mechanically connected to. The earth's atmosphere is often used as a pressure reservoir.

It is important that these two types of instruments are distinct. A meter does not perform its task accurately if it behaves like a reservoir of the state variable it is trying to measure. If, for example, a thermometer, were to act as a temperature reservoir it would alter the temperature of the system being measured, and the reading would be incorrect. Ideal meters have no effect on the state variables of the system they are measuring.

Thermodynamics and life

The laws of thermodynamics hold important implications beyond applications in engineering and physics and have led to countless discussions and debates about how ordered systems and life itself could have arisen in a world relentlessly trending toward disorder. One of the keys to resolving differences of viewpoints about life and the laws of thermodynamics lies in being clear about the level of system being discussed. At one level, for example, the answer is simple—life on planet earth represents a pocket of order in a larger system still trending toward disorder and the life on earth is sustained only by energy from the sun flowing through the system and always trending eventually toward a lower energy. Hence, life is not in violation of the second law of thermodynamics.

For many, the explanation of how that pocket of order came to exist lies in the process of natural selection operating on heritable variability, while others presume some sort of supernatural intervention was required to bring about humans and today's richly diverse biological world. Systems theorists, approaching the topic from a different angle speak of "syntropy" as a tendency of systems to move toward order, in effect acting as a counterbalance to the entropy identified by physicists and claimed by many biologists.[14]

Nobel laureate physicist, Ilya Prigogine (1917-2003) took thermodynamics in new directions by concentrating on "dissipative systems," which were ordered systems surviving in non-equilibrium states sustained by a steady intake of energy from the environment. Living systems are the model dissipative systems, but he greatly expanded the concepts to such diverse applications as traffic patterns in cities, the growth of cancer cells, and the stability of insect communities.[15]

Thermodynamic potentials

As can be derived from the energy balance equation on a thermodynamic system there exist energetic quantities called thermodynamic potentials, being the quantitative measure of the stored energy in the system. The five most well known potentials are:

| Internal energy | |

| Helmholtz free energy | |

| Enthalpy | |

| Gibbs free energy | |

| Grand potential |

Potentials are used to measure energy changes in systems as they evolve from an initial state to a final state. The potential used depends on the constraints of the system, such as constant temperature or pressure. Internal energy is the internal energy of the system, enthalpy is the internal energy of the system plus the energy related to pressure-volume work, and Helmholtz and Gibbs energy are the energies available in a system to do useful work when the temperature and volume or the pressure and temperature are fixed, respectively.

Notes

- ↑ Pierre Perrot, A to Z of Thermodynamics (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1998, ISBN 0-19-856552-6).

- ↑ Rudolf Clausius, On the Motive Power of Heat, and on the Laws Which can be Deduced from it for the Theory of Heat (New York: Poggendorff's Annalen der Physick, 1850, ISBN 0-486-59065-8).

- ↑ H.C. Van Ness, Understanding Thermodynamics (New York: Dover Publications, Inc., 1969, ISBN 0-486-63277-6).

- ↑ J.S. Dugdale, Entropy and its Physical Meaning (London: Taylor and Francis, ISBN 0-7484-0569-0).

- ↑ Hyperphysics, Heat and Thermodynamics. Retrieved January 30, 2008.

- ↑ J.M. Smith, H.C. Van Ness, M.M. Abbott, Introduction to Chemical Engineering Thermodynamics (New York: McGraw Hill, 2005, ISBN 0-07-310445-0).

- ↑ J.R. Partington, A Short History of Chemistry (New York: Dover, 1989, ISBN 0-486-65977-1).

- ↑ Rudolf Clausius, Mechanical Theory of Heat. Retrieved October 5, 2007.

- ↑ William T. Kelvin, An Account of Carnot's Theory of the Motive Power of Heat—with Numerical Results Deduced from Regnault's Experiments on Steam. Retrieved October 5, 2007.

- ↑ Yunus A. Cengel and Michael A. Boles, Thermodynamics—An Engineering Approach (New York: McGraw-Hill, 2005, ISBN 0-07-310768-9).

- ↑ Leonard K. Nash, Elements of Statistical Thermodynamics, 2nd edition (New York: Dover Publications, Inc., 1974, ISBN 0-486-44978-5).

- ↑ Willard Gibbs, The Scientific Papers of J. Willard Gibbs, Volume One: Thermodynamics (Woodbridge, CT: Ox Bow Press, 1993, ISBN 0-918024-77-3).

- ↑ Gilbert N. Lewis and Merle Randall, Thermodynamics and the Free Energy of Chemical Substances (New York: McGraw-Hill Book Co. Inc., 1923).

- ↑ Entropy Law, All About Entropy, The Laws of Thermodynamics, and Order from Disorder. Retrieved January 30, 2008.

- ↑ University of Texas, In Memoriam Ilya Prigogine. Retrieved January 31, 2008.

References

ISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Cengel, Yunus A., and Michael A. Boles. 2002. Thermodynamics—An Engineering Approach. New York: McGraw Hill. ISBN 0-07-238332-1.

- Dunning-Davies, Jeremy. 1997. Concise Thermodynamics: Principles and Applications. Chichester, UK: Horwood Publishing. ISBN 1-8985-6315-2.

- Goldstein, Martin, and F. Inge. 1993. The Refrigerator and the Universe. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-75325-9.

- Kroemer, Herbert, and Kittel Charles. 1980. Thermal Physics. New York: W.H. Freeman Company. ISBN 0-7167-1088-9.

External links

All links retrieved February 6, 2020.

- Thermodynamics at ScienceWorld.

- Shakespeare & Thermodynamics.

- Biochemistry Thermodynamics.

- 180+ Variations of the 5 Laws.

- Thermodynamic Evolution.

- Thermodynamics and Statistical Mechanics.

| General subfields within physics | |

Atomic, molecular, and optical physics | Classical mechanics | Condensed matter physics | Continuum mechanics | Electromagnetism | General relativity | Particle physics | Quantum field theory | Quantum mechanics | Special relativity | Statistical mechanics | Thermodynamics |

|

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.

↧ Download as ZWI file | Last modified: 02/03/2023 22:43:11 | 106 views

☰ Source: https://www.newworldencyclopedia.org/entry/Thermodynamics | License: CC BY-SA 3.0

ZWI signed:

ZWI signed:

KSF

KSF