Australia

From Britannica 11th Edition (1911)

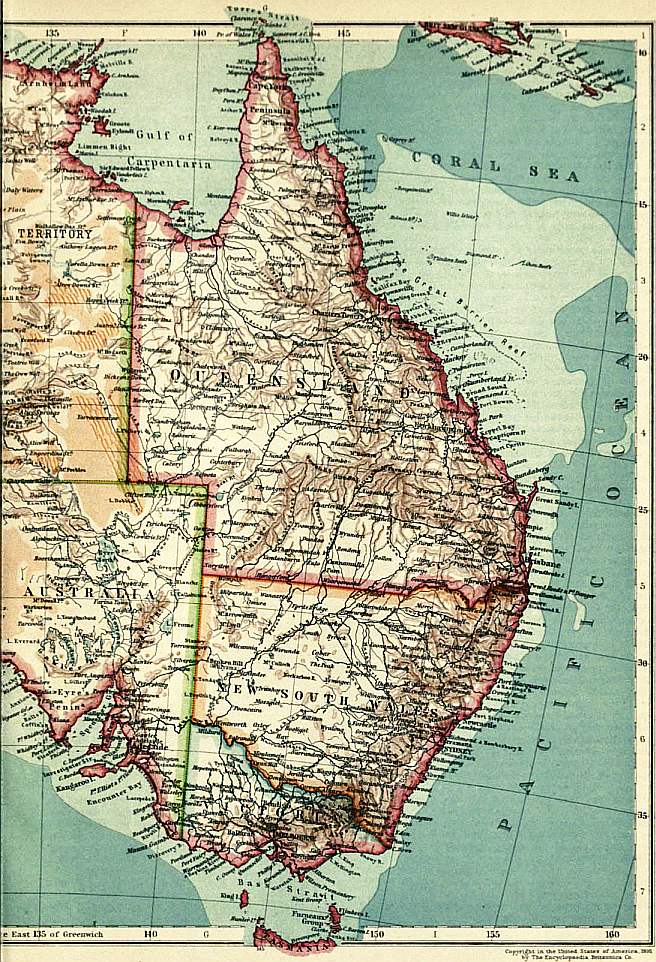

From Britannica 11th Edition (1911) Australia, the only continent entirely in the southern hemisphere. It lies between 10° 39′ and 39° 11½’ S., and between 113° 5′ and 153° 16′ E. Its greatest length is 2400 m. from east to west, and the greatest breadth 1971 m. from north to south. The area is, approximately, 2,946,691 sq. m., with a coast line measuring about 8850 m. This is equal to 1 m. to each 333 sq. m. of land, the smallest proportion of coast shown by any of the continents.

Physical Geography

Physiography.—The salient features of the Australian continent are its compact outline, the absence of navigable rivers communicating with the interior, the absence of active volcanoes or snow-capped mountains, its General character. isolation from other lands, and its antiquity. Some of the most profound changes that have taken place on this globe occurred in Mesozoic times, and a great portion of Australia was already dry land when vast tracts of Europe and Asia were submerged; in this sense, therefore, Australia has been rightly referred to as one of the oldest existing land surfaces. It has been described as at once the largest island and the smallest continent on the globe. The general contours exemplify the law of geographers in regard to continents, viz. as to their having a high border around a depressed interior, and the highest mountains on the side of the greatest ocean. On the N. Australia is bounded by the Timor Sea, the Arafura Sea and Torres Strait; on the E. by the Pacific Ocean; on the S. by Bass Strait and the Southern Ocean; and on the W. by the Indian Ocean. It stands up from the ocean depths in three fairly well-marked terraces. The basal plain of these terraces is the bed of the ocean, which on the Pacific side has an average depth of 15,000 ft. From this profound foundation rise Australia, New Guinea and Melanesia, in varying slopes. The first ledge rising from the ocean floor has a depth averaging 8000 ft. below sea-level. The outer edge of this ledge is roughly parallel to the coast of Western Australia, and more than 150 m. from the land. Round the Australian Bight it continues parallel to the coast, until south of Spencer Gulf (the basal ledge still averaging 8000 ft. in depth) it sweeps southwards to lat. 55°, and forms a submarine promontory 1000 m. long. The edge of the abysmal area comes close to the eastern coasts of Tasmania and New South Wales, approaching to within 60 m. of Cape Howe. The terrace closest to the land, known as the continental shelf, has an average depth of 600 ft., and connects Australia, New Guinea, and Tasmania in one unbroken sweep. Compared with other continents, the Australian continental shelf is extremely narrow, and there are points on the eastern coast where the land plunges down to oceanic depths with an abruptness rarely paralleled. Off the Queensland coast the shelf broadens, its outer edge being lined by the seaward face of the Great Barrier Reef. From Torres Strait to Dampier Land the shelf spreads out, and connects Australia with New Guinea and the Malay Archipelago. An elongation of the shelf to the south joins Tasmania with the mainland. The vertical relief of the land above the ocean is a very important factor in determining the climate as well as the distribution of the fauna and flora of a continent.

The land mass of Australia rises to a mean height much less than that of any other continent; and the chief mountain systems are parallel to, and not far from, the coast-line. Thus, taking the continent as a whole, it may be described as a plateau, fringed by a low-lying well-watered coast, with a depressed, and for the most part arid, interior. A great plain, covering quite 500,000 sq. m., occupies a position a little to the east of a meridional line bisecting the continent, and south of the 22nd degree, but portions of it stretch upwards to the low-lying country south of the Gulf of Carpentaria. The contour of the continent in latitude 30° 5′ is as follows:—a short strip of coastal plain; then a sharp incline rising to a mountain range 4000 ft. above sea-level, at a distance of 40 m. from the coast. From this a gently-sloping plateau extends to almost due north of Spencer Gulf, at which point its height has fallen almost to sea-level. Then there is a gentle rise to the low steppes, 500 to 1000 ft. above sea-level. A further gentle rise in the high steppes leads to the mountains of the West Australian coast, and another strip of low-lying coastal land to the sea.

With a circumference of 8000 m. Australia presents a contour wonderfully devoid of inlets from the sea except on its northern shores, where the coast-line is largely indented. The Gulf of Carpentaria, situated in the north, is enclosed on the east by the projection of Cape York, and on the west by Arnheim Land, and forms the principal bay on the whole coast, measuring about 6° of long. by 6° of lat. Farther to the west, Van Diemen’s Gulf, though much smaller, forms a better-protected bay, having Melville Island between it and the ocean; while beyond this, Queen’s Channel and Cambridge Gulf form inlets about 14° 50′ S. On the north-west of the continent the coast-line is much broken, the chief indentations being Admiralty Gulf, Collier Bay and King Sound, on the shores of Tasman Land. Western Australia, again, is not favoured with many inlets, Exmouth Gulf and Shark’s Bay being the only bays of any size. The same remark may be made of the rest of the sea-board; for, with the exception of Spencer Gulf, the Gulf of St Vincent and Port Phillip on the south, and Moreton Bay, Hervey Bay and Broad Sound on the east, the coast-line is singularly uniform. There are, however, numerous spacious harbours, especially on the eastern coast, which are referred to in the detailed articles dealing with the different states. The Great Barrier Reef forms the prominent feature off the north-east coast of Australia; its extent from north to south is 1200 m., and it is therefore the greatest of all coral reefs. The channel between the reef and the coast is in places 70 m. wide and 400 ft. deep. There are a few clear openings in the outer rampart which the reef presents to the ocean. These are opposite to the large estuaries of the Queensland rivers, and might be thought to have been caused by fresh water from the land. The breaks are, however, some 30 to 90 m. away from land and more probably were caused by subsidence; the old river-channels known to exist below sea-level, as well as the former land connexion with New Guinea, seem to point to the conditions assumed in Darwin’s well-known subsidence theory, and any facts that appear to be inconsistent with the theory of a steady and prolonged subsidence are explainable by the assumption of a slight upheaval.

With the exception of Tasmania there are no important islands belonging geographically to Australia, for New Guinea, Timor and other islands of the East Indian archipelago, though not removed any great distance from the continent, do not belong to its system. On the east coast there are a few small and unimportant islands. In Bass Strait are Flinders Island, about 800 sq. m. in area, Clarke Island, and a few other small islands. Kangaroo Island, at the entrance of St Vincent Gulf, is one of the largest islands on the Australian coast, measuring 80 m. from east to west with an average width of 20 m. Numerous small islands lie off the western coast, but none has any commercial importance. On the north coast are Melville and Bathurst Islands; the former, which is 75 m. long and 38 m. broad, is fertile and well watered. These islands are opposite Port Darwin, and to the westward of the large inlet known as Van Diemen’s Gulf. In the Gulf of Carpentaria are numerous islands, the largest bearing the Dutch name of Groote Eylandt.

Along the full length of the eastern coast extends a succession of mountain chains. The vast Cordillera of the Great Dividing Range originates in the south-eastern corner of the continent, and runs parallel with and close to the eastern Mountains. shore, through the states of Victoria and New South Wales, right up to the far-distant York Peninsula in Queensland. In Victoria the greatest elevation is reached in the peaks of Mount Bogong (6508 ft.) and Mount Feathertop (6303 ft.), both of which lie north of the Dividing Range; in the main range Mount Hotham (6100 ft.) and Mount Cobberas (6025 ft.) are the highest summits. In New South Wales, but close to the Victorian border, are found the loftiest peaks of Australia, Mount Kosciusco and Mount Townsend, rising to heights of 7328 and 7260 ft. respectively. The range is here called the Muniong, but farther north it receives the name of Monaro Range; the latter has a much reduced altitude, its average being only about 2000 ft. As the tableland runs northward it decreases both in height and width, until it narrows to a few miles only, with an elevation of scarcely 1500 ft.; under the name of the Blue Mountains the plateau widens again and increases in altitude, the chief peaks being Mount Clarence (4000 ft.), Mount Victoria (3525 ft.), and Mount Hay (3270 ft.). The Dividing Range decreases north of the Blue Mountains, until as a mere ridge it divides the waters of the coastal rivers from those flowing to the Darling. The mass widens out once more in the Liverpool Range, where the highest peak, Mount Oxley, reaches 4500 ft., and farther north, in the New England Range, Ben Lomond reaches an elevation of 5000 ft. Near the Queensland border, Mount Lindsay, in the Macpherson Range, rises to a height of 5500 ft. In the latitude of Brisbane the chain swerves inland; no other peak north of this reaches higher than Mount Bartle Frere in the Bellenden Ker Range (5438 ft.). The Southern Ocean system of the Victorian Dividing Range hardly attains to the dignity of high mountains. An eastern system in South Australia touches at a few points a height of 3000 ft.; and the Stirling Range, belonging to the south-western system of South Australia, reaches to 2340 ft. There are no mountains behind the Great Australian Bight. On the west the Darling Range faces the Indian Ocean, and extends from Point D’Entrecasteaux to the Murchison river. North of the Murchison, Mount Augustus and Mount Bruce, with their connecting highlands, cut off the coastal drainage from the interior; but no point on the north-west coast reaches a greater altitude than 4000 ft. Several minor ranges, the topography of which is little known, extend from Cambridge Gulf, behind a very much broken coast-line, to Limmen Bight on the Gulf of Carpentaria. Nothing is more remarkable than the contrast between the aspect of the coastal ranges on the north-east and on the south-east of the continent. The higher Australian peaks in the south-east look just what they are, the worn and denuded stumps of mountains, standing for untold ages above the sea. Their shoulders are lifted high above the tree-line. Their summits stand out gaunt and lonely in an unbroken solitude. Having left the tree-line far behind him, nothing is visible to the traveller for miles around but barren peaks and torn crags in indescribable confusion. A verdure of herbage clothes the valleys that have been scooped from the summits downwards. But there are no perpetual snow-fields, no glaciers creep down these valleys, and no alpine hamlets ever appear to break the monotony. The mountains of the north-east, on the contrary, are clothed to their summits with a rich and varied flora. Naked crags, when they do appear, lift themselves from a sea of green, and a tropical vegetation, quite Malaysian in character, covers everything.

The absence of active volcanoes in Australia is a state of things, in a geological sense, quite new to the continent. Some of the volcanoes of the western districts of Victoria have been in eruption probably subsequent to the advent of the black-fellow. In some instances the cones are quite intact, and the beds of ash and scoriae are as yet almost unaffected by denuding agencies. Late in the Tertiary period vast sheets of lava poured from many points of the Great Dividing Range of eastern Australia. But it is notable that all recent volcanic action was confined to a wide belt parallel to the coast. No evidences of recent lava flows can be found in the interior over the great alluvial plain, the Lower, or the Higher Steppes. Nor has the continent, as a whole, in recent times been subjected to any violent earth tremors; though in 1873, to the north of Lake Amadeus, in central Australia, Ernest Giles records the occurrence of earthquake shocks violent enough to dislodge considerable rock masses.

Australia possesses one mountain which, though not a volcano, is a “burning mountain.” This is Mount Wingen, situated in a spur of the Liverpool Range and close to the town of Scone. Its fires are not volcanic, but result from the combustion of coal some distance underground, giving off much smoke and steam; geologists estimate that the burning has been going on for at least 800 years.

The coastal belt of Australia is everywhere well watered, with the exception of the country around the Great Australian Bight and Spencer Gulf. Flowing into the Pacific Ocean on the east coast there are some fine rivers, but the majority have Rivers. short and rapid courses. In Queensland a succession of rivers falls into the Pacific from Cape York to the southern boundary of the state. The Burdekin is the finest of these, draining an area of 53,500 sq. m., and emptying into Upstart Bay; it receives numerous tributaries in its course, and carries a large body of fresh water even in the driest seasons. The Fitzroy river is the second in point of size; it drains an area of 55,600 sq. m., and receives several tributary streams during its course to Keppel Bay. The Brisbane river, falling into Moreton Bay, is important chiefly from the fact that the city of Brisbane is situated on its banks. In New South Wales there are several important rivers, the largest of which is the Hunter, draining 11,000 sq. m., and having a course of 200 m. Taking them from north to south, the principal rivers are the Richmond, Clarence, Macleay, Hastings, Manning, Hunter, Hawkesbury and Shoalhaven. The Snowy river has the greater part of its course in New South Wales, but its mouth and the last 120 m. are in Victoria. The other rivers worth mentioning are the Yarra, entering the sea at Port Phillip, Hopkins and Glenelg. The Murray (q.v.), the greatest river of Australia, debouches into Lake Alexandrina, and thence into the sea at Encounter Bay in South Australia. There are no other rivers of importance in South Australia, but the Torrens and the Gawler may be mentioned. Westward of South Australia, on the shores of the Australian Bight, there is a stretch of country 300 m. in length unpierced by any streams, large or small, but west of the bight, towards Cape Leeuwin, some small rivers enter the sea. The south-west coast is watered by a few streams, but none of any size; amongst these is the Swan, upon which Perth, the capital of Western Australia, is built. Between the Swan and North-West Cape the principal rivers are the Greenough, Murchison and Gascoyne; on the north-west coast, the Ashburton, Fortescue and De Grey; and in the Kimberley district, the Fitzroy, Panton, Prince Regent and the Ord. In the Northern Territory are several fine rivers. The Victoria river is navigable for large vessels for a distance of about 43 m. from the sea, and small vessels may ascend for another 80 m. The Fitzmaurice, discharging into the estuary of the Victoria, is also a large stream. The Daly, which in its upper course is called the Katherine, is navigable for a considerable distance, and small vessels are able to ascend over 100 m. The Adelaide, discharging into Adam Bay, has been navigated by large vessels for about 38 m., and small vessels ascend still farther. The South Alligator river, flowing into Van Diemen’s Gulf, is also a fine stream, navigable for over 30 m. by large vessels; the East Alligator river, falling into the same gulf, has been navigated for 40 m. Besides those mentioned, there are a number of smaller rivers discharging on the north coast, and on the west shore of the Gulf of Carpentaria the Roper river discharges itself into Limmen Bight. The Roper is a magnificent stream, navigable for about 75 or 80 m. by vessels of the largest tonnage, and light draught vessels can ascend 20 m. farther. Along the portion of the south shore of the Gulf of Carpentaria which belongs to Queensland and the east coast, many large rivers discharge their waters, amongst them the Norman, Flinders, Leichhardt, Albert and Gregory on the southern shore, and the Batavia, Archer, Coleman, Mitchell, Staaten and Gilbert on the eastern shore. The rivers flowing into the Gulf of Carpentaria, as well as those in the Northern Territory, drain country which is subject to regular monsoonal rains, and have the general characteristics of sub-tropical rivers.

The network of streams forming the tributaries of the Darling and Murray system give an idea of a well-watered country. The so-called rivers have a strong flow only after heavy rains, and some of them do not ever reach the main drainage line. Flood waters disappear often within a distance of a few miles, being absorbed by porous soil, stretches of sand, and sometimes by the underlying bed-rocks. In many cases the rivers as they approach the main stream break up into numerous branches, or spread their waters over vast flats. This is especially the case with the tributaries of the Darling on its left bank, where in seasons of great rains these rivers overspread their banks and flood the flat country for miles around and thus reach the main stream. Lieutenant John Oxley went down the Lachlan (1817) during one of these periods of flood, and the great plains appeared to him to be the fringe of a vast inland sea. As a matter of fact, they are an alluvial deposit spread out by the same flood waters. The great rivers of Australia, draining inland, carve out valleys, dissolve limestone, and spread out their deposit over the plains when the waters become too sluggish to bear their burden farther. From a geological standpoint, the Great Australian Plain and the fertile valley of the Nile have had a similar origin. Taking the Lachlan as one type of Australian river, we find it takes its rise amongst the precipitous and almost unexplored valleys of the Great Dividing Range. With the help of its tributaries it acts as a denuding agent for 14,000 sq. m. of country, and carries its burden of sediment westwards. A point is reached about 200 m. from the Dividing Range, where the river ceases to act as a denuding agent, and the area of deposition begins, at a level of 250 ft. above the sea, but before the waters can reach the ocean they have still to travel about 1000 m.

The Darling is reckoned amongst the longest rivers in the world, for it is navigable, part of the year, from Walgett to its confluence with the Murray, 1758 m., and then to the sea, a further distance of 587 m.—making in all 2345 m. of navigable water. But this gives no correct idea of the true character of the Darling, for it can hardly be said to drain its own watershed. From the sources of its various tributaries to the town of Bourke, the river may be described as draining a watershed. But from Bourke to the sea, 550 m. in a direct line, the river gives rather than receives water from the country it flows through.

The annual rainfall and the area of the catchment afford no measure whatever as to the size of a river in the interior of Australia. The discharge of the Darling river at Bourke does not amount to more than 10% of the rainfall over the country which it drains. It was this remarkable fact which first led to the idea that, as the rainfall could not be accounted for either by evaporation or by the river discharge, much of the 90% unaccounted for must sink into the ground, and in part be absorbed by some underlying bed-rock. All Australian rivers, except the Murray and the Murrumbidgee, depend entirely and directly on the rainfall. They are flooded after rain, and in seasons of drought many of them, especially the tributaries of the Darling, become chains of ponds. Springs which would equalize the discharge of rivers by continuing to pour water into their beds after the rainy season has passed seem entirely absent in the interior. Nor are there any snowfields to feed rivers, as in the other continents. More remarkable still, over large tracts of country the water seems disposed to flow away from, rather than to, the river-beds. As the low-lying plains are altogether an alluvial deposit, the coarser sediments accumulate in the regions where the river first overflows its banks to spread out over the plains. The country nearest the river receiving the heaviest deposit becomes in this way the highest ground, and so continues until a “break-away” occurs, when a new river-bed is formed, and the same process of deposition and accumulation is repeated. As the general level of the country is raised by successive alluvial deposits, the more ancient river-beds become buried, but being still connected with the newer rivers at some point or other, they continue to absorb water. This underground network of old river-beds underlying the great alluvial plains must be filled to repletion before flood waters will flow over the surface. It is not surprising, therefore, that comparatively little of the rainfall over the vast extent of the great central plain ever reaches the sea by way of the river systems; indeed these systems as usually shown on the maps leave a false impression as to the actual condition of things.

The great alluvial plain is one of Australia’s most notable inland features; its extent is upwards of 500,000 sq. m., lying east of 135° W. and extending right across the continent from the Gulf of Carpentaria to the Murray river. The interior Steppes. of the continent west of 135° and north of the Musgrave ranges is usually termed by geographers the Australian Steppes. It is entirely different in all essential features from the great alluvial plains. Its prevailing aspect is characterized by flat and terraced hills, capped by desert sandstone, with stone-covered flats stretching over long distances. The country round Lake Eyre, where some of the land is actually below sea-level, comes under this heading. The higher steppes, as far as they are known, consist of Ordovician and Cambrian rocks, with an average elevation of 1500 to 3000 ft. above sea-level. Over this country water-courses are shown on maps. These run in wet seasons, but in every instance for a short distance only, and sooner or later they are lost in sand-hills, where their waters disappear and a line of stunted gum-trees (Eucalyptus rostrata) is all that is present to indicate that there may be even a soakage to mark the abandoned course. The steppes cover a surface of 400,000 sq. m., and from this vast expanse not a drop of the scanty rainfall reaches the sea; there is no leading drainage system and there are no rivers. Another notable feature of the interior is the so-called lake area, a district stretching to the north of Spencer Gulf. These Lakes. lakes are expanses of brackish waters that spread or contract as the season is one of drought or rain. In seasons of drought they are hardly more than swamps and mud flats, which for a time may become a grassy plain, or desolate coast encrusted with salt. The country around is the dreariest imaginable, the surface is a dead level, there is no heavy timber and practically no settlement. Lake Torrens, the largest of these depressions, sometimes forms a sheet of water 100 m. in length. To the north again stretches Lake Eyre, and to the west Lake Gairdner. Some of these lake-beds are at or slightly below sea-level, so that a very slight depression of the land to the south of them would connect much of the interior with the Southern Ocean.

Geology.—The states of Australia are divided by natural boundaries, which separate geographical areas having different characters, owing, mainly, to their different geological structures. Hence the general stratigraphical geology can be most conveniently summarized for each state separately, dealing here with the geological history of Australia as a whole. Australia is essentially the fragment of a great plateau land of Archean rocks. It consists in the main of an Archean block or “coign,” which still occupies nearly the whole of the western half of the continent, outcrops in north-eastern Queensland, forms the foundation of southern New South Wales and eastern Victoria, and is exposed in western Victoria, in Tasmania, and in the western flank of the Southern Alps of New Zealand. These areas of Archean rocks were doubtless once continuous. But they have been separated by the foundering of the Coral Sea and the Tasman Sea, which divided the continent of Australia from the islands of the Australasian festoon; and the foundering of the band across Australia, from the Gulf of Carpentaria, through western Queensland and western New South Wales, to the lower basin of the Murray, has separated the Archean areas of eastern and western Australia. The breaking up of the old Archean foundation block began in Cambrian and Ordovician times. A narrow Cambrian sea must have extended across central Australia from the Kimberley Goldfield in the north-west, through Tempe Downs and the Macdonnell chain in central Australia, to the South Australian highlands, central Victoria at Mansfield, and northern Tasmania. Cambrian rocks occur in each of these districts, and they are best developed in the South Australian highlands, where they include a long belt of contemporary glacial deposits. Marine Ordovician rocks were deposited along the same general course. They are best developed in the Macdonnell chain in central Australia and in Victoria, where the fullest sequence is known; while they also extended north-eastward from Victoria into New South Wales, where, as yet, no Cambrian rocks have been found. The Silurian system was marked by the retreat of the sea from central Australia; but the sea still covered a band across Victoria, from the coast to the Murray basin, passing to the east of Melbourne. This Silurian sea was less extensive than the Ordovician in Victoria; but it appears to have been wider in New South Wales and in Queensland. The best Silurian sequence is in New South Wales. Silurian rocks are well developed in western Tasmania, and the Silurian sea must have washed the south-western corner of the continent, if the rocks of the Stirling Range be rightly identified as of this age.

The Devonian system includes a complex series of deposits, which are of most interest in eastern Australia. This period was marked by intense earth movements, which affected the whole of the east Australian highlands. The Lower Devonian beds are in the main terrestrial, or coarse littoral deposits, and volcanic rocks. The Middle Devonian was marked by the same great transgression as in Europe and America; it produced inland seas, extending into Victoria, New South Wales and Queensland, in which were deposited limestones with a rich coral fauna. The Upper Devonian was a period of marine retreat; the crustal disturbances of the Lower Devonian were renewed and great quartz-pebble beaches were formed on the rising shore lines, producing the West Coast Range conglomerates of Tasmania, and the similar rocks to the south-east of Mansfield in Victoria. Intrusions of granitic massifs in the Devonian period formed the primitive mountain axis of Victoria, which extends east and west across the state and forms the nucleus of the Victorian highlands. Similar granitic intrusions occurred in New South Wales and Queensland, and built up a mountain chain, which ran north and south across the continent; its worn-down stumps now form the east Australian highlands.

The Carboniferous period began with a marine transgression, enabling limestones to form in Tasmania and New South Wales; and at the same time the sea first got in along the western edge of the western plateau, depositing the Carboniferous rocks of the Gascoyne basin and the coastal plain of north-western Australia. The Upper Carboniferous period was in the main terrestrial, and during it were laid down the coal-seams of New South Wales; they are best developed in the basin of the Hunter river, and they extend southward, covered by Mesozoic deposits, beyond Sydney. The Coal Measures become narrower in the south, until, owing to the eastward projection of the highlands, the Lower Palaeozoic rocks reach the coast. The coal-seams must have been formed in well-watered, lowland forests, at the foot of a high mountain range, built up by the Devonian earth movements. The mountains both in Victoria and New South Wales were snow-capped, and glaciers flowed down their flanks and laid down Carboniferous glacial deposits, which are still preserved in basins that flank the mountain ranges, such as the famous conglomerates of Bacchus Marsh, Heathcote and the Loddon valley in Victoria, and of Branxton and other localities in New South Wales. The age of the glacial deposits is later than the Glossopteris flora and occurs early in the time of the Gangamopteris flora. Kitson’s work in Tasmania shows that there also the glacial beds may be correlated with the lower or Greta Coal Measures of New South Wales.

The Permian deposits are best developed in New South Wales and Tasmania, where their characters show the continuation of the Carboniferous conditions. The Mesozoic begins with a Triassic land period in the mainland of Australia; while the islands of the Australasian festoon contain the Triassic marine limestones, which fringe the whole of the Pacific. The Triassic beds are best known in New South Wales, where round Sydney they include a series of sandstones and shales. They also occur in northern Tasmania.

The Jurassic system is represented by two types. In Victoria, Tasmania, northern New South Wales and Queensland, there are Jurassic terrestrial deposits, containing the coal seams of Victoria, of the Clarence basin of north-eastern New South Wales, and of the Ipswich series in Queensland; the same beds range far inland on the western slopes of the east Australian highlands in New South Wales and Queensland and they occur, with coal-seams, at Leigh’s Creek, at the northern foot of the South Australian highlands. They are also preserved in basins on the western plateau, as shown by brown coal deposits passed through in the Lake Phillipson bore. The second and marine type of the Jurassics occurs in Western Australia, on the coastal plain skirting the western foot of the western plateau.

The Cretaceous period was initiated by the subsidence of a large area to the south of the Gulf of Carpentaria, whereby a Lower Cretaceous sea spread southward, across western Queensland, western New South Wales and the north-eastern districts of South Australia. In this sea were laid down the shales of the Rolling Downs formation. The sea does not appear to have extended completely across Australia, breaking it into halves, for a projection from the Archean plateau of Western Australia extended as far east as the South Australian highlands, and thence probably continued eastward, till it joined the Victorian highlands. The Cretaceous sea gradually receded and the plains of the Rolling Downs formation formed on its floor were covered by the sub-aerial and lacustrine deposits of the Desert Sandstone.

The Kainozoic period opened with fresh earth movements, the most striking evidence of which are the volcanic outbreaks all round the Australian coasts. These movements in the south-east formed the Great Valley of Victoria, which traverses nearly the whole of the state between the Victorian highlands to the north, and the Jurassic sandstones of the Otway Ranges and the hills of south Gippsland. In this valley were laid down, either in Eocene or Oligocene times, a great series of lake beds and thick accumulations of brown coal. Similar deposits, of approximately the same age, occur in Tasmania and New Zealand; and at about the same time there began the Kainozoic volcanic period of Australasia. The first eruptions piled up huge domes of lavas rich in soda, including the geburite-dacites and sölvsbergites of Mount Macedon in Victoria, and the kenyte and tephrite domes of Dunedin, in New Zealand. These rocks were followed by the outpouring of the extensive older basalts in the Great Valley of Victoria and on the highlands of eastern Victoria, and also in New South Wales and Queensland. Then followed a marine transgression along most of the southern coast of Australia. The sea encroached far on the land from the Great Australian Bight and there formed the limestones of the Nullarbor Plains. The sea extended up the Murray basin into the western plains of New South Wales. Farther east the sea was interrupted by the still existing land-connexion between Tasmania and Victoria; but beyond it, the marine deposits are found again, fringing the coasts of eastern Gippsland and Croajingolong. These marine deposits are not found anywhere along the eastern coast of Australia; but they occur, and reach about the same height above sea-level, in New Guinea, and are widely developed in New Zealand. No doubt eastern Australia then extended far out into the Tasman Sea. The great monoclinal fold which formed the eastern face of the east Australian highlands, west of Sydney, is of later age. After this marine period was brought to a close the sea retreated. Tasmania and Victoria were separated by the foundering of Bass Strait, and at the same time the formation of the rift valley of Spencer Gulf, and Lake Torrens, isolated the South Australian highlands from the Eyre Peninsula and the Westralian plateau. Earth movements are still taking place both along Bass Strait and the Great Valley of South Australia, and apparently along the whole length of the southern coast of Australia.

The Flowing Wells of Central Australia.—The clays of the Rolling Downs formation overlie a series of sands and drifts, saturated with water under high pressure, which discharges at the surface as a flowing well, when a borehole pierces the impermeable cover. The first of these wells was opened at Kallara in the west of New South Wales in 1880. In 1882, Dr W.L. Jack concluded that western Queensland might be a deep artesian basin. The Blackhall bore, put down at his advice from 1885 to 1888, reached a water-bearing layer at the depth of 1645 ft. and discharged 291,000 gallons a day. It was the first of the deep artesian wells of the continent. As the plains on the Rolling Downs formation are mostly waterless, the discovery of this deep reservoir of water has been of great aid in the development of central Australia. In Queensland to the 30th of June 1904, 973 wells had been sunk, of which 596 were flowing wells, and the total flow was 62,635,722 cub. ft. a day. The deepest well is that at Whitewood, 5046 ft. deep. In New South Wales by the 30th of June 1903, the government had put down 101 bores producing 66 flowing wells and 22 sub-artesian wells, with a total discharge of 54,000,000 gallons a day; and there were also 144 successful private wells. In South Australia there are 38 deep bores, from 20 of which there is a flow of 6,250,000 gallons a day.

The wells were first called artesian in the belief that the ascent of the water in them was due to the hydrostatic pressure of water at a higher level in the Queensland hills. The well-water was supposed to have percolated underground, through the Blythesdale Braystone, which outcrops in patches on the eastern edge of the Rolling Downs formation. But the Blythesdale Braystone is a small local formation, unable to supply all the wells that have been sunk; and many of the wells derive their water from the Jurassic shales and mudstones. The difference in level between the outcrop of the assumed eastern intake and of the wells is often so small, in comparison with their distance apart, that the friction would completely sop up the whole of the available hydrostatic head. Many of the well-waters contain gases; thus the town of Roma is lighted by natural gas which escapes from its well. The chemical characters of the well-waters, the irregular distribution of the water-pressure, the distribution of the underground thermal gradients, and the occurrence in some of the wells of a tidal rise and fall of a varying period, are facts which are not explained on the simple hydrostatic theory. J.W. Gregory has maintained (Dead Heart of Australia, 1906, pp. 273-341) that the ascent of water in these wells is due to the tension of the included gases and the pressure of overlying sheets of rocks, and that some of the water is of plutonic origin.1

Climate.—The Australian continent, extending over 28° of latitude, might be expected to show a considerable diversity of climate. In reality, however, it experiences fewer climatic variations than the other great continents, owing to its distance (28°) from the Antarctic circle and (11°) from the equator. There is, besides, a powerful determining cause in the uniform character and undivided extent of its dry interior. The plains and steppes already described lie either within or close to the tropics. They present to the fierce play of the sun almost a level surface, so that during the day that surface becomes intensely heated and at night gives off its heat by radiation. Ordinarily the alternate expansion and contraction of the atmosphere which takes place under such circumstances would draw in a supply of moisture from the ocean, but the heated interior, covering some 900,000 sq. m., is so immense, that the moist air from the ocean does not come in sufficient supply, nor are there mountain chains to intercept the clouds which from time to time are formed; so that two-fifths of Australia, comprising a region stretching from the Australian Bight to 20° S. and from 117° to 142° E., receives less than an average of 10 in. of rain throughout the year, and a considerable portion of this region has less than 5 in. No part of Victoria and very little of Queensland and New South Wales lie within this area. The rest of the continent may be considered as well watered. The north-west coast, particularly the portions north of Cambridge Gulf and the shores of the Gulf of Carpentaria, are favoured with an annual visitation of the monsoon from December to March, penetrating as far as 500 m. into the continent, and sweeping sometimes across western and southern Queensland to the northern interior of New South Wales. It is this tropical downpour that fills and floods the rivers flowing into Lake Eyre and those falling into the Darling on its right bank. The whole of the east coast of the continent is well watered. From Cape York almost to the tropic of Capricorn the rainfall exceeds 50 in. and ranges to over 70 in. At Brisbane the fall is 50 in., and portions of the New South Wales coast receive a like quantity, but speaking generally the fall is from 30 in. to 40 in. The southern shores of the continent receive much less rain. From Cape Howe to Melbourne the fall may be taken at from 30 in. to 40 in., Melbourne itself having an average of 25.6 in. West of Port Phillip the fall is less, averaging 20 in. to 30 in., diminishing greatly away from the coast. Along the shores of Encounter Bay and St Vincent and Spencer Gulfs, the precipitation ranges from 10 to 20 in., the yearly rainfall at Adelaide is a little less than 21 in., while the head of Spencer Gulf is within the 5 to 10 in. district. The rest of the southern coast west as far as 124° E., with the exception of the southern projection of Eyre Peninsula, which receives from 10 to 20 in., belongs to the district with from 5 to 10 in. annual rainfall. The south-western angle of the continent, bounded by a line drawn diagonally from Jurien river to Cape Riche, has an average of from 30 to 40 in. annual rainfall, diminishing to about 20 to 30 in. in the country along the diagonal line. The remainder of the south and west coast from 124° E. to York Sound in the Kimberley district for a distance of some 150 m. inland has a fall ranging from 10 to 20 in. The 10 to 20 in. rainfall band circles across the continent through the middle of the Northern Territory, embraces the entire centre and south-west of Queensland, with the exception of the extreme south-western angle of the state, and includes the whole of the interior of New South Wales to a line about 200 m. from the coast, as well as the western and northern portions of Victoria and South Australia south of the Murray.

The area of Australia subject to a rainfall of from 10 to 20 in. is 843,000 sq. m. On the seaward side of this area in the north and east is the 20 to 30 in. annual rainfall area, and still nearer the sea are the exceptionally well-watered districts. The following table shows the area of the rainfall zones in square miles:—

| Rainfall. | Rainfall Area in sq. m. |

| Under 10 inches | 1,219,600 |

| 10 to 20 ” | 843,100 |

| 20 to 30 ” | 399,900 |

| 30 to 40 ” | 225,700 |

| 40 to 50 ” | 140,300 |

| 50 to 60 ” | 47,900 |

| 60 to 70 ” | 56,100 |

| Over 70 ” | 14,100 |

| ———— | |

| Total | 2,946,700 |

The tropic of Capricorn divides Australia into two parts. Of these the northern or intertropical portion contains 1,145,000 sq. m., comprising half of Queensland, the Northern Territory, and the north-western divisions of Western Australia. The whole of New South Wales, Victoria and South Australia proper, half of Queensland, and more than half of Western Australia, comprising 1,801,700 sq. m., are without the tropics. In a region so extensive very great varieties of climate are naturally to be expected, but it may be stated as a general law that the climate of Australia is milder than that of corresponding lands in the northern hemisphere. During July, which is the coldest month in southern latitudes, one-half of Australia has a mean temperature ranging from 45° to 61°, and the other half from 62° to 80°. The following are the areas subject to the various average temperatures during the month referred to:—

| Temperature Fahr. | Area in sq. m. |

| 45°-50° | 18,800 |

| 50°-55° | 506,300 |

| 55°-60° | 681,800 |

| 60°-65° | 834,400 |

| 65°-70° | 515,000 |

| 70°-75° | 275,900 |

| 75°-80° | 24,500 |

The temperature in December ranges from 60° to above 95° Fahr., half of Australia having a mean temperature below 84°. Dividing the land into zones of average summer temperature, the following are the areas which would fall to each:—

| Temperature Fahr. | Area in sq. m. |

| 60°-65° | 67,800 |

| 65°-70° | 63,700 |

| 70°-75° | 352,300 |

| 75°-80° | 439,200 |

| 80°-85° | 733,600 |

| 85°-90° | 570,600 |

| 90°-95° | 584,100 |

| 95° and over | 135,400 |

Judging from the figures just given, it must be conceded that a considerable area of the continent is not adapted for colonization by European races. The region with a mean summer temperature in excess of 95° Fahr. is the interior of the Northern Territory north of the 20th parallel; and the whole of the country, excepting the seaboard, lying between the meridians of 120° and 140°, and north of the 25th parallel, has a mean temperature in excess of 90° Fahr.

The area of Australia is so large that the characteristics of its climate will not be understood without reference to the individual states. About one-half of the colony of Queensland lies in the tropics, the remaining area lying between the Queensland. tropic and 29° S. The temperature, however, has a daily range less than that of other countries under the same isothermal lines. This circumstance is due to the sea-breezes, which blow with great regularity, and temper what would otherwise be an excessive heat. The hot winds which prevail during the summer in some of the other colonies are unknown in Queensland. Of course, in a territory of such large extent there are many varieties of climate, and the heat is greater along the coast than on the elevated lands of the interior. In the northern parts of the colony the high temperature is very trying to persons of European descent. The mean temperature at Brisbane, during December, January and February, is about 76°, while during the months of June, July and August it averages about 60°. Brisbane, however, is situated near the extreme southern end of the colony, and its average temperature is considerably less than that of many of the towns farther north. Thus the winter in Rockhampton averages nearly 65°, while the summer heat rises almost to 85°; and at Townsville and Normanton the average temperature is still higher. The average rainfall along the coast is high, especially in the north, where it ranges from 60 to 70 in. per annum, and along a strip of country south from Cape Melville to Rockingham Bay the average rainfall exceeds 70 in. At Brisbane the rainfall is about 50 in., taking an average of forty years. A large area of the interior is watered to the extent of 20 to 30 in. per annum, but in the west and south, more remote than from 250 to 300 m., there is a rainfall of less than 20 in.

Climatically, New South Wales is divided into three marked divisions. The coastal region has an average summer temperature ranging from 78° in the north to 67° in the south, with a winter temperature of from 59° to 52°. Taking the New South Wales. district generally, the difference between the mean summer and mean winter temperatures may be set down as averaging not more than 20°, a range smaller than is found in most other parts of the world. Sydney, situated in latitude 33° 51′ S., has a mean temperature of 62.9° Fahr., which corresponds with that of Barcelona in Spain and of Toulon in France, the former of these being in latitude 41° 22′ N. and the latter in 43° 7′ N. At Sydney the mean summer temperature is 70.8° Fahr., and that of winter 53.9°. The range is thus 16.9° Fahr. At Naples, where the mean temperature for the year is about the same as at Sydney, the summer temperature reaches a mean of 74.4°, and the mean of winter is 47.6°, with a range 26.8°. The mean temperature of Sydney for a long series of years was spring 62°, summer 71°, autumn 64°, winter 54°.

Passing from the coast to the tableland, a distinct climatic region is entered. Cooma, with a mean summer temperature of 65.4°, and a mean winter temperature of 41.4°, may be taken as illustrative of the climate of the southern tableland, and Armidale of the northern. The yearly average temperature of the latter is scarcely 65.5°, while the summer only reaches 67.7°, and the winter falls to 44.4°.

The climatic conditions of the western districts of the state are entirely different from those of the other two regions. The summer is hot, but on the whole the climate is very healthy. The town of Bourke, lying on the upper Darling, may be taken as an example of many of the interior districts, and illustrates peculiarly well the defects as well as the excellencies of the climate of the whole region. Bourke has exactly the same latitude as Cairo, yet its mean summer temperature is 1.3° less, and its mean annual temperature 4° less than that of the Egyptian city. New Orleans, also on the same parallel, is 4° hotter in summer. As regards winter temperature Bourke leaves little to be desired. The mean winter reading of the thermometer is 54.7, and accompanied as this is by clear skies and an absence of snow, the season is both pleasant and invigorating. The rainfall of New South Wales ranges from an annual average of 64 in. at various points on the northern coast, and at Kiandra in the Monaro district, to 9 in. at Milparinka in the trans-Darling district. The coastal districts average about 42 in. per annum, the tablelands 32 in., and the western interior has an average as low as 20 in. At Sydney, the average rainfall, since observations were commenced, has been 50 in.

The climate of Victoria does not differ greatly from that of New South Wales. The heat, however, is generally less intense in summer, and the cold greater in winter. Melbourne, which stands in latitude 37° 50′ S., has a mean temperature of 57.3°, Victoria. and therefore corresponds with Washington in the United States, Madrid, Lisbon and Messina. The difference between summer and winter is, however, less at Melbourne than at any of the places mentioned, the result of a long series of observations being spring 57°, summer 65.3°, autumn 58.7°, and winter 49.2°. The highest recorded temperature in the shade at Melbourne is 110.7°, and the lowest 27°, but it is rare for the summer heat to exceed 85°, or for the winter temperature in the daytime to fall below 40°. Ballarat, the second city of Victoria, lies above 100 m. west from Melbourne at a height of 1400 ft. above sea-level. It has a minimum temperature of 29°, and a maximum of 104.5°, the average yearly mean being 54.1°. The rainfall of Melbourne averages 25.58 in., the mean number of rainy days being 131.

South Australia proper extends over 26 degrees of latitude, and naturally presents considerable variations of climate. The coldest months are June, July and August, during which the temperature is very agreeable, averaging 53.6°, 51.7°, South Australia. and 54° in those months respectively. On the plains slight frosts occur occasionally, and ice is sometimes seen on the highlands. In summer the sun has great power, and the temperature reaches 100° in the shade, with hot winds blowing from the interior. The weather on the whole is remarkably dry. At Adelaide there are on an average 120 rainy days per annum, with a mean rainfall of 20-88 in. The country is naturally very healthful, as evidence of which may be mentioned that no great epidemic has ever visited the state.

Western Australia has practically only two seasons, the winter or wet season, which commences in April and ends in October, and the summer or dry season, which comprises the remainder of the Year. During the wet season frequent and heavy Western Australia. rains fall, and thunderstorms, with sharp showers, occur in the summer, especially on the north-west coast, which is sometimes visited by hurricanes of great violence. In the southern and early-settled parts of the state the mean temperature is about 64°, but in the more northern portions the heat is excessive, though the dryness of the atmosphere makes it preferable to moist tropical climates. The average rainfall at Perth is 33 in. per annum.

The climate of the Northern Territory is extremely not, except on the elevated tablelands; altogether, the temperature of this part of the continent is very similar to that of northern Queensland, and the climate is not favourable to Europeans. The rainfall in the extreme north, especially in January and February, is very heavy, and the annual average along the coast is about 63 in. The whole of the peninsula north of 15° S. has a rainfall considerably exceeding 40 in. This region is backed by a belt of about 100 m. wide, in which the rainfall is from 30 to 40 in., from which inwards the rainfall gradually declines until between Central Mount Stuart and Macdonnell ranges it falls to between 5 and 10 in.

Fauna and Flora.—The origin of the fauna and flora of Australia has attracted considerable attention. Much accumulated evidence, biological and geological, has pointed to a southern extension of India, an eastern extension of South Africa, and a western extension of Australia into the Indian Ocean. The comparative richness of proteaceous plants in Western Australia and South Africa first suggested a common source for these primitive types. Dr H.O. Forbes drew attention to a certain community amongst birds and other vertebrates, invertebrates, and amongst plants, on all the lands stretching towards the south pole. A theory was therefore propounded that these known types were all derived from a continent which has been named Antarctica. The supposed continent extended across the south pole, practically joining Australia and South America. Just as we have evidence of a former mild climate in the arctic regions, so a similar mild climate has been postulated for Antarctica. Modern naturalists consider that many of the problems of Australia’s remarkable fauna and flora can be best explained by the following hypothesis:—The region now covered by the antarctic ice-cap was in early Tertiary times favoured by a mild climate; here lay an antarctic continent or archipelago. From an area corresponding to what is now South America there entered a fauna and flora, which, after undergoing modification, passed by way of Tasmania to Australia. These immigrants then developed, with some exceptions, into the present Australian flora and fauna. This theory has advanced from the position of a disparaged heresy to acceptance by leading thinkers. The discovery as fossil, in South America, of primitive or ancestral forms of marsupials has given it much support. One of these, Prothylacinus, is regarded as the forerunner of the marsupial wolf of Tasmania. An interesting link between divergent marsupial families, still living in Ecuador, the Coenolestes, is another discovery of recent years. On the Australian side the fact that Tasmania is richest in marsupial types indicates the gate by which they entered. It is not to be supposed that this antarctic element, to which Professor Tate has applied the name Euronotian, entered a desert barren of all life. Previous to its arrival Australia doubtless possessed considerable vegetation and a scanty fauna, chiefly invertebrate. At a comparatively recent date Australia received its third and newest constituent. The islands of Torres Strait have been shown to be the denuded remnant of a former extension of Cape York peninsula in North Queensland. Previous to the existence of the strait, and across its site, there poured into Australia a wealth of Papuan forms. Along the Pacific slope of the Queensland Cordillera these found in soil and climate a congenial home. Among the plants the wild banana, pepper, orange and mangosteen, rhododendron, epiphytic orchids and the palm; among mammals the bats and rats; among birds the cassowary and rifle birds; and among reptiles the crocodile and tree snakes, characterize this element. The numerous facts, geological, geographical and biological, which when linked together lend great support to this theory, have been well worked out in Australia by Mr Charles Hedley of the Australian Museum, Sydney.

The zoology of Australia and Tasmania presents a very conspicuous point of difference from that of other regions of the globe, in the prevalence of non-placental mammalia. The vast majority of the mammalia are provided with an organ in Fauna. the uterus, by which, before the birth of their young, a vascular connexion is maintained between the embryo and the parent animal. There are two orders, the Marsupialia and the Monotremata, which do not possess this organ; both these are found in Australia, to which region indeed they are not absolutely confined.

The geographical limits of the marsupials are very interesting. The opossums of America are marsupials, though not showing anomalies as great as kangaroos and bandicoots (in their feet), and Myrmecobius (in the number of teeth). Except the opossums, no single living marsupial is known outside the Australian zoological region. The forms of life characteristic of India and the Malay peninsula come down to the island of Bali. Bali is separated from Lombok by a strait not more than 15 m. wide. Yet this narrow belt of water is the boundary line between the Australasian and the Indian regions. The zoological boundary passing through the Bali Strait is called “Wallace’s line,” after the eminent naturalist who was its discoverer. He showed that not only as regards beasts, but also as regards birds, these regions are thus sharply limited. Australia, he pointed out, has no woodpeckers and no pheasants, which are widely-spread Indian birds. Instead of these it has mound-making turkeys, honey-suckers, cockatoos and brush-tongued lories, all of which are found nowhere else in the world.

The marsupials constitute two-thirds of all the Australian species of mammals. It is the well-known peculiarity of this order that the female has a pouch or fold of skin upon her abdomen, in which she can place the young for suckling within reach of her teats. The opossum of America is the only species out of Australasia which is thus provided. Australia is inhabited by at least 110 different species of marsupials, which is about two-thirds of the known species; these have been arranged in five tribes, according to the food they eat, viz., the grass-eaters (kangaroos), the root-eaters (wombats), the insect-eaters (bandicoots), the flesh-eaters (native cats and rats), and the fruit-eaters (phalangers).

The kangaroo (Macropus) lives in droves in the open grassy plains. Several smaller forms of the same general appearance are known as wallabies, and are common everywhere. The kangaroo and most of its congeners show an extraordinary disproportion of the hind limbs to the fore part of the body. The rock wallabies again have short tarsi of the hind legs, with a long pliable tail for climbing, like that of the tree kangaroo of New Guinea, or that of the jerboa. Of the larger kangaroos, which attain a weight of 200 ℔ and more, eight species are named, only one of which is found in Western Australia. Fossil bones of extinct kangaroo species are met with; these kangaroos must have been of enormous size, twice or thrice that of any species now living.

There are some twenty smaller species in Australia and Tasmania, besides the rock wallabies and the hare kangaroos; these last are wonderfully swift, making clear jumps 8 or 10 ft. high. Other terrestrial marsupials are the wombat (Phascolomys), a large, clumsy, burrowing animal, not unlike a pig, which attains a weight of from 60 to 100 ℔; the bandicoot (Perameles), a rat-like creature whose depredations annoy the agriculturist; the native cat (Dasyurus), noted robber of the poultry yard; the Tasmanian wolf (Thylacinus), which preys on large game; and the recently discovered Notoryctes, a small animal which burrows like a mole in the desert of the interior. Arboreal species include the well-known opossums (Phalanger); the extraordinary tree-kangaroo of the Queensland tropics; the flying squirrel, which expands a membrane between the legs and arms, and by its aid makes long sailing jumps from tree to tree; and the native bear (Phascolarctos), an animal with no affinities to the bear, and having a long soft fur and no tail.

The Myrmecobius of Western Australia is a bushy-tailed ant-eater about the size of a squirrel, and from its lineage and structure of more than passing interest. It is, Mivart remarks, a survival of a very ancient state of things. It had ancestors in a flourishing condition during the Secondary epoch. Its congeners even then lived in England, as is proved by the fact that their relics have been found in the Stonesfield oolitic rocks, the deposition of which is separated from that which gave rise to the Paris Tertiary strata by an abyss of past time which we cannot venture to express even in thousands of years.

We pass on to the other curious order of non-placental mammals, that of the Monotremata, so called from the structure of their organs of evacuation with a single orifice, as in birds. Their abdominal bones are like those of the marsupials; and they are furnished with pouches for their young, but have no teats, the milk being distilled into their pouches from the mammary glands. Australia and Tasmania possess two animals of this order—the echidna, or spiny ant-eater (hairy in Tasmania), and the Platypus anatinus, the duckbilled water mole, otherwise named the Ornithorhynchus paradoxus. This odd animal is provided with a bill or beak, which is not, like that of a bird, affixed to the skeleton, but is merely attached to the skin and muscles.

Australia has no apes, monkeys or baboons, and no ruminant beasts. The comparatively few indigenous placental mammals, besides the dingo or wild dog—which, however, may have come from the islands north of this continent—are of the bat tribe and of the rodent or rat tribe. There are four species of large fruit-eating bats, called flying foxes, twenty of insect-eating bats, above twenty of land-rats, and five of water-rats. The sea produces three different seals, which often ascend rivers from the coast, and can live in lagoons of fresh water; many cetaceans, besides the “right whale” and sperm whale; and the dugong, found on the northern shores, which yields a valuable medicinal oil.

The birds of Australia in their number and variety of species may be deemed some compensation for its poverty of mammals; yet it will not stand comparison in this respect with regions of Africa and South America in the same latitudes. The black swan was thought remarkable when discovered, as belying an old Latin proverb. There is also a white eagle. The vulture is wanting. Sixty species of parrots, some of them very handsome, are found in Australia. The emu corresponds with the African and Arabian ostrich, the rhea of South America, and the cassowary of the Moluccas and New Guinea. In New Zealand this group is represented by the apteryx, as it formerly was by the gigantic moa, the remains of which have been found likewise in Queensland. The graceful Menura superba, or lyre-bird, with its tail feathers spread in the shape of a lyre, is a very characteristic form. The mound-raising megapodes, the bower-building satin-birds, and several others, display peculiar habits. The honey-eaters present a great diversity of plumage. There are also many kinds of game birds, pigeons, ducks, geese, plovers and quails. The ornithology of New South Wales and Queensland is more varied and interesting than that of the other provinces.

As for reptiles, Australia has a few tortoises, all of one family, and not of great size. The “leathery turtle,” which is herbivorous, and yields abundance of oil, has been caught at sea off the Illawarra coast so large as 9 ft. in length. The saurians or lizards are numerous, chiefly on dry sandy or rocky ground in the tropical region. The great crocodile of Queensland has been known to attain a length of 30 ft.; there is a smaller one about 6 ft. in length to be met with in the shallow lagoons of the interior of the Northern Territory. Lizards occur in great profusion and variety. The monitor, or fork-tongued lizard, which burrows in the earth, climbs and swims, is said to grow to a length of 8 to 9 ft. This species and many others do not extend to Tasmania. The monitor is popularly known as the goanna, a name derived from the iguana, an entirely different animal. There are about twenty kinds of night-lizards, and many which hibernate. One species can utter a cry when pained or alarmed, and the tall-standing frilled lizard can lift its forelegs, and squat or hop like a kangaroo. There is also the Moloch horridus of South and Western Australia, covered with tubercles bearing large spines, which give it a very strange aspect. This and some other lizards have power to change their colour, not only from light to dark, but over some portions of their bodies, from yellow to grey or red. Frogs of many kinds are plentiful, the brilliant green frogs being especially conspicuous and noisy. Australia is rich in snakes, and has more than a hundred different kinds. Most of these are venomous, but all are not equally dreaded. Five rather common species are certainly deadly—the death adder, the brown, the black, the superb and the tiger snakes. During the colder months these reptiles remain in a torpid state. No certain cure has been or is likely to be discovered for their poison, but in less serious cases strychnine has been used with advantage. In tropical waters a sea snake is found, which, though very poisonous, rarely bites. Among the inoffensive species are counted the graceful green “tree snake,” which pursues frogs, birds and lizards to the topmost branches of the forest; also several species of pythons, the commonest of which is known as the carpet snake. These great reptiles may attain a length of 10 ft.; they feed on small animals which they crush to death in their folds.

The Australian seas are inhabited by many fishes of the same genera as exist in the southern parts of Asia and Africa. Of those peculiar to Australian waters may be mentioned the arripis, represented by what is called among the colonists a salmon trout. A very fine freshwater fish is the Murray cod, which sometimes weighs 100 ℔; and the golden perch, found in the same river, has rare beauty of colour. Among the sea fish, the schnapper is of great value as an article of food, and its weight comes up to 50 ℔ This is the Pagrus unicolor, of the family of Sparidae, which includes also the bream. Its colours are beautiful, pink and red with a silvery gloss; but the male as it grows old takes on a singular deformity of the head, with a swelling in the shape of a monstrous human-like nose. These fish frequent rocky shoals off the eastern coast and are caught in numbers outside Port Jackson for the Sydney market. Two species of mackerel, differing somewhat from the European species, are also caught on the coasts. The so-called red garnet, a pretty fish, with hues of carmine and blue stripes on its head, is much esteemed for the table. The Trigla polyommata, or flying garnet, is a greater beauty, with its body of crimson and silver, and its large pectoral fins, spread like wings, of a rich green, bordered with purple, and relieved by a black and white spot. Whiting, mullet, gar-fish, rock cod and many others known by local names, are in the lists of edible fishes belonging to New South Wales and Victoria. Oysters abound on the eastern coast, and on the shelving banks of a vast extent of the northern coast the pearl oyster is the source of a considerable industry.

Two existing fishes may be mentioned as ranking in interest with the Myrmecobius (ant-eater) in the eyes of the naturalist. These are the Ceratodus Forsteri and the Port Jackson shark. The “mud-fish” of Queensland (Ceratodus Forsteri) belongs to an ancient order of fishes—the Dipnoi, only a few species of which have survived from past geological periods. The Dipnoi show a distinct transition between fishes and amphibia. So far the mud-fish has been found only in the Mary and the Burnett rivers. Hardly of less scientific interest is the Port Jackson shark (Heterodontus). It is a harmless helmeted ground-shark, living on molluscs, and almost the sole survivor of a genus abundant in the Secondary rocks of Europe.

The eastern parts of Australia are very much richer both in their botany and in their zoology than any of the other parts. This is due in part to the different physical conditions there prevailing and in part to the invasion of the north-eastern Flora. portion of the continent by a number of plants characteristically Melanesian. This element was introduced via Torres Strait, and spread down the Queensland coast to portions of the New South Wales littoral, and also round the Gulf of Carpentaria, but has never been able to obtain a hold in the more arid interior. It has so completely obliterated the original flora, that a Queensland coast jungle is almost an exact replication of what may be seen on the opposite shores of the straits, in New Guinea. This wealth of plant life is confined to the littoral and the coastal valleys, but the central valleys and the plateaux have, if not a varied flora, a considerable wealth of timber trees in every way superior to the flora inland in the same latitudes. In the interior there is little change in the general aspect of the vegetation, from the Australian Bight to the region of Carpentaria, where the exotic element begins. Behind the luxuriant jungles of the sub-tropical coast, once over the main range, we find the purely Australian flora with its apparent sameness and sombre dulness. Physical surroundings rather than latitude determine the character of the flora. The contour lines showing the heights above sea-level are the directions along which species spread to form zones. Putting aside the exotic vegetation of the north and east coast-line, the Australian bush gains its peculiar character from the prevalence of the so-called gum-trees (Eucalyptus) and the acacias, of which last there are 300 species, but the eucalypts above all are everywhere. Dwarfed eucalypts fringe the tree-limit on Mount Kosciusco, and the soakages in the parched interior are indicated by a line of the same trees, stunted and straggling. Over the vast continent from Wilson’s Promontory to Cape York, north, south, east and west—where anything can grow—there will be found a gum-tree. The eucalypts are remarkable for the oil secreted in their leaves, and the large quantity of astringent resin of their bark. This resinous exudation (Kino) somewhat resembles gum, hence the name “gum” tree. It will not dissolve in water as gums do, but it is soluble in alcohol, as resin usually is. Many of the gum-trees throw off their bark, so that it hangs in long dry strips from the trunk and branches, a feature familiar in “bush” pictures. The bark, resin and “oils” of the eucalyptus are well known as commercial products. As early as 1866, tannic acid, gallic acid, wood spirit, acetic acid, essential oil and eucalyptol were produced from various species of eucalyptus, and researches made by Australian chemists, notably by Messrs. Baker and Smith of the Sydney Technical College, have brought to light many other valuable products likely to prove of commercial value. The genus Eucalyptus numbers more than 150 species, and provides some of the most durable timbers known. The iron-bark of the eastern coast uplands is well known (Eucalyptus sideroxylon), and is so called from the hardness of the wood, the bark not being remarkable except for its rugged and blackened aspect. Samples of this timber have been studied after forty-three years’ immersion in sea-water. Portions most liable to destruction, those parts between the tide marks, were found perfectly sound, and showed no signs of the ravages of marine organisms. Other valuable timber trees of the eastern portion of the continent are the blackbutt, tallow-wood, spotted gum, red gum, mahogany, and blue gum, eucalyptus; and the turpentine (Syncarpia laurifolia), which has proved to be more resistant to the attacks of teredo than any other timber and is largely used in wharf construction in infested waters. There are also several extremely valuable soft timbers, the principal being red cedar (Cedrela Toona), silky oak (Grevillea robusta), beech and a variety of teak, with several important species of pine. The red gum forests of the Murray valley and the pine forests bordering the Great Plains are important and valuable. In Western Australia there are extensive forests of hardwood, principally jarrah (Eucalyptus marginata), a very durable timber; 14,000 sq. m. of country are covered with this species. Jarrah timber is nearly impervious to the attacks of the teredo, and there is good evidence to show that, exposed to wear and weather, or placed under the soil, or used as submarine piles, the wood remained intact after nearly fifty years’ trial. The following figures show the high density of Australian timber:—

| Australian timber. | Specific gravity. |

| Jarrah | 1.12 |

| Grey iron-bark | 1.18 |

| Red iron-bark | 1.22 |

| Forest oak | 1.21 |

| Tallow wood | 1.23 |

| Mahogany | 1.20 |

| Grey gum | 917 |

| Red gum | 995 |

| European timber. | Specific gravity. |

| Ash | .753 |

| Beech | .690 |

| Chestnut | .535 |

| British oak | .99 |

The resistance to breaking or rupture of Australian timber is very high; grey iron-bark with a specific gravity of 1.18 has a modulus of rupture of 17,900 ℔ per sq. in. compared with 11,800 ℔ for British oak with a specific gravity of .69 to .99. No Australian timber in the foregoing list has a less modulus than 13,100 ℔ per sq. in.

Various “scrubs” characterize the interior, differing very widely from the coastal scrubs. “Mallee” scrub occupies large tracts of South Australia and Victoria, covering probably an extent of 16,000 sq. m. The mallee is a species of eucalyptus growing 12 to 14 ft. high. The tree breaks into thin stems close to the ground, and these branch again and again, the leaves being developed umbrella-fashion on the outer branches. The mallee scrub appears like a forest of dried osier, growing so close that it is not always easy to ride through it. Hardly a leaf is visible to the height of one’s head; but above, a crown of thick leather-like leaves shuts out the sunlight. The ground below is perfectly bare, and there is no water. Nothing could add to the sterility and the monotony of these mallee scrubs. “Mulga” scrub is a somewhat similar thicket, covering large areas. The tree in this instance is one of the acacias, a genus distributed through all parts of the continent. Some species have rather elegant blossoms, known to the settlers as “wattle.” They serve admirably to break the sombre and monotonous aspect of the Australian vegetation. Two species of acacia are remarkable for the delicate and violet-like perfume of their wood—myall and yarran. The majority of the species of Acacia are edible and serve as reserve fodder for sheep and cattle. In the alluvial portions of the interior salsolaceous plants—saltbush, bluebush, cottonbush—are invaluable to the pastoralist, and to their presence the pre-eminence of Australia as a wool-producing country is largely due.

Grasses and herbage in great variety constitute the most valuable element of Australian flora from the commercial point of view. The herbage for the most part grows with marvellous rapidity after a spring or autumn shower and forms a natural shelter for the more stable growth of nutritious grasses.

Under the system of grazing practised throughout Australia it is customary to allow sheep, cattle and horses to run at large all the year round within enormous enclosures and to depend entirely upon the natural growth of grass for their subsistence. Proteaceous plants, although not exclusively Australian, are exceedingly characteristic of Australian scenery, and are counted amongst the oldest flowering plants of the world. The order is easily distinguished by the hard, dry, woody texture of the leaves and the dehiscent fruits. They are found in New Zealand and also in New Caledonia, their greatest developments being on the south-west of the Australian continent. Proteaceae are found also in Tierra del Fuego and Chile. They are also abundant in South Africa, where the order forms the most conspicuous feature of vegetation. The range in species is very limited, no one being common to eastern and western Australia. The chief genera are banksia (honeysuckle), and hakea (needle bush).

The Moreton Bay pine (Araucaria Cunninghamii) is reckoned amongst the giants of the forest. The genus is associated with one long extinct in Europe. Moreton Bay pine is chiefly known by the utility of its wood. Another species, A. Bidwillii, or the bunya-bunya, afforded food in its nut-like seeds to the aborigines. A most remarkable form of vegetation in the north-west is the gouty-stemmed tree (Adansonia Gregorii), one of the Malvaceae. It is related closely to the famous baobab of tropical Africa. The “grass-tree” (Xanthorrhoea), of the uplands and coast regions, is peculiarly Australian in its aspect. It is seen as a clump of wire-like leaves, a few feet in diameter, surrounding a stem, hardly thicker than a walking-stick, rising to a height of 10 or 12 ft. This terminates in a long spike thickly studded with white blossoms. The grass-tree gives as distinct a character to an Australian picture as the agave and cactus do to the Mexican landscape. With these might be associated the gigantic lily of Queensland (Nymphaea gigantea), the leaves of which float on water, and are quite 18 in. across. There is also a gigantic lily (Doryanthes excelsa) which grows to a height of 15 feet. The “flame tree” is a most conspicuous feature of an Illawarra landscape, the largest racemes of crimson red suggesting the name. The waratah or native tulip, the magnificent flowering head of which, with the kangaroo, is symbolic of the country, is one of the Proteaceae. The natives were accustomed to suck its tubular flowers for the honey they contained. The “nardoo” seed, on which the aborigines sometimes contrived to exist, is a creeping plant, growing plentifully in swamps and shallow pools, and belongs to the natural order of Marsileaceae. The spore-cases remain after the plant is dried up and withered. These are collected by the natives, and are known over most of the continent as nardoo.

No speculation of hypothesis has been propounded to account satisfactorily for the origin of the Australian flora. As a step towards such hypothesis it has been noted that the Antarctic, the South African, and the Australian floras have many types in common. There is also to a limited extent a European element present. One thing is certain, that there is in Australia a flora that is a remnant of a vegetation once widely distributed. Heer has described such Australian genera as Banksia, Eucalyptus, Grevillea and Hakea from the Miocene of Switzerland. Another point agreed upon is that the Australian flora is one of vast antiquity. There are genera so far removed from every living genus that many connecting links must have become extinct. The region extending round the south-western extremity of the continent has a peculiarly characteristic assemblage of typical Australian forms, notably a great abundance of the Proteaceae. This flora, isolated by arid country from the rest of the continent, has evidently derived its plant life from an outside source, probably from lands no longer existing.

Political and Economic Conditions