Sakhalin Koreans

From Nwe

From Nwe | Sakhalin Koreans | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total population | ||||||||||||

| over 55,000[1] | ||||||||||||

| Regions with significant populations | ||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||

| Languages | ||||||||||||

| Russian, Korean | ||||||||||||

| Religions | ||||||||||||

| Protestantism,[2][3] others? | ||||||||||||

| Related ethnic groups | ||||||||||||

| Korean people, Koryo-saram |

Sakhalin Koreans (Russian: Сахалинские корейцы/Sakhalinskie Koreytsi or Корейцы Сахалина/Koreytsi Sakhalina; Korean: 사할린 한국인/Sahallin Hangugin) denotes Russians citizens and/or residents of Korean descent living on Sakhalin Island who trace their roots to the immigrants from the Gyeongsang and Jeolla provinces of Korea during the late 1930s and early 1940s, the latter half of the Japanese colonial era.

The Sakhalin Koreans experienced slaughter at the hands of the Russians during the early stages of the Soviet occupation of Sakhalin. In the decades following, those Koreans refused repatriation to Korea suffered discrimination as they have in Japan, Manchuria, the United States and other nations of diaspora. Still, over the past five decades, Koreans in Sakhalin have proven themselves by enduring through their ethnic ties, loyalty to country, and hard work ethic. First, second, and third generation Sakhalin Koreans, by and large, show little interest in returning to their motherland, South Korea.

Overview

During the 1930s and early 1940s, the Empire of Japan controlled the southern half of Sakhalin Island, then known as Karafuto Prefecture, recruiting or forcing Korean laborers into service, shipping them to Karafuto to fill labor shortages during World War II. The Red Army invaded Karafuto days before Japan's surrender; while all but a few Japanese repatriated successfully, Russia refused to grant permission to one-third of the Koreans to depart either for Japan or their home towns in Korea. For the next 40 years, they lived in exile. In 1985, the Japanese government offered transit rights and funding for the repatriation of the original group of Sakhalin Koreans; only 1,500 of them returned to South Korea in the next two decades. The vast majority of Koreans chose instead to stay on Sakhalin.

Due to language and ethic roots, Sakhalin Koreans may or may not identify themselves as Koryo-saram. The term "Koryo-saram" applies to all Koreans in the former USSR, but typically refers to ethnic Koreans from Hamgyŏng province whose ancestors emigrated to the Russian Far East in the nineteenth century, later deported to Central Asia by the Russians. Many Sakhalin Koreans feel that Koreans from Central Asia look down on them, complicating the issue of self-identification .[4]

History

Under Japanese colonialism

Origins

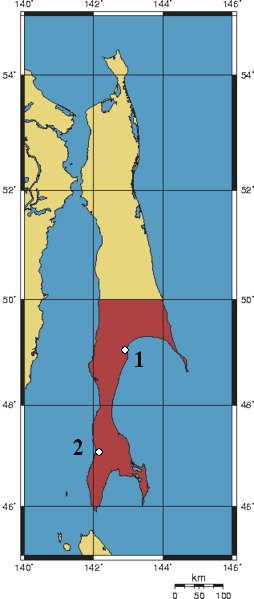

1: Poronaysk, near Kamishisuka (上敷香)

2: Kholmsk, near Mizuho Village (瑞穂村)

██ Soviet Union ██ Empire of Japan

Korean immigration to Sakhalin began as early as the 1910s, when the Mitsui Group began recruiting laborers from the peninsula for their mining operations.[5] In 1920, ten years after the annexation of Korea by Japan, fewer than one thousand Koreans lived in the whole of Karafuto Prefecture, overwhelmingly male.[6] Aside from an influx of refugees from the Maritimes, who escaped to Karafuto during the Russian Revolution of 1917, the number of Koreans in the province rose slowly; as late as the mid 1930s, fewer than 6,000 Koreans lived in Karafuto.[5][7] As Japan's war effort picked up, the Japanese government sought to put more people on the ground in the sparsely-populated prefecture to ensure their control of the territory and fill the increasing labor demands of the coal mines and lumber yards. Recruiters turned to sourcing workers from the Korean peninsula to take advantage of the low wages there; at one point, over 150,000 Koreans worked on the island.[8] Of those, around 10,000 mine workers relocated to Japan prior to the War's end, and present-day Sakhalin Koreans' efforts to locate them proved futile.[9]

The Imperial Japanese Army in Karafuto frequently used local ethnic minorities (Oroks, Nivkhs, and Ainu) to conduct intelligence-gathering activities, because, as indigenous inhabitants, their presence escaped suspicion on the Soviet half of the island. Although ethnic Koreans also lived on both sides of the border, the Japanese use of Koreans as spies proved common, as the Karafuto police suspected support for the independence movement among Koreans. Soviet suspicion towards Korean nationalism, along with fears that the Korean community might revolt, led to the 1937 deportation of Koreans from Sakhalin and the Russian Far East.[10]

The Soviet invasion and Japanese massacres

The Soviet Union invaded the Japanese portion of Sakhalin on August 11, 1945, slaughtering 20,000 civilians. In the ensuing confusion, a rumor spread that ethnic Koreans served as spies for the Soviet Union, leading to massacres of Koreans by Japanese police and civilians. Despite the scant information about the massacres, two incidents have of massacres have been confirmed: the incident in Kamishisuka on August 18, 1945, and the incident in Mizuho Village, which lasted from August 20 to August 23, 1945.

In Kamishisuka, the Japanese police arrested nineteen Koreans on charges of spy activities; eighteen turned up shot dead within the police station the next day.[11] The sole survivor, a Korean known only by his Japanese name Nakata, had survived by hiding in a toilet; he later offered testimony about the event.[12] In Mizuho Village, Japanese fleeing Soviet troops who had landed at Kholmsk claimed that the Koreans cooperated with the Red Army, pillaging Japanese property as well. Though Koreans and Japanese worked alongside each other in the village on farms and construction projects, the Japanese civilians turned against their Korean neighbours, killing 27 between August 20th and 23rd.[10] Other Koreans may have been killed to cover up evidence of Japanese atrocities committed during the evacuation: one woman interviewed by a US-Russian joint commission investigating the issue of Allied prisoners of war held by the Imperial Japanese Army in camps on Sakhalin reported that her ethnic Korean lover had been murdered by Japanese troops after he had witnessed mass shootings of hundreds of American prisoners of war.[13]

Integration into the Soviet Union

Repatriation refused

In the years after the Soviet invasion, most of the 400,000 Japanese civilians either evacuated during the war or left voluntarily under the auspices of the US-USSR Agreement on Repatriation, signed in December 1946. Many of the 150,000 Koreans on the island safely returned to mainland Japan, and some went to the northern half of the Korean peninsula; the Japanese rejected roughly 43,000 repatriation to Japan. The South Koreans also refused repatriation in fear of allowing communists bend on instigating revolution into the sector.[8] Stalin also reportedly blocked their departure because he wanted to retain them as coal miners in Sakhalin. For years, the Sakhalin Koreans existed as a stateless people forced to stay in Sakhalin.[14] In 1957, Seoul appealed for Tokyo's assistance to secure the departure of ethnic Koreans from Sakhalin via Japan, but Tokyo delayed action on the request, blaming Soviet intransigence for the lack of progress in resolving the issue. Japan continued their policy of only granting entrance to Sakhalin Koreans married to Japanese citizens, or those with a Japanese parent.[15]

In an effort to integrate the Korean laborers unfamiliar with the Soviet system and unable to speak Russian, local authorities set up schools using the Korean language in instruction. The Russia suspicion that the Sakhalin Koreans had been "infected with the Japanese spirit," led to authorities mistrust, refusing to allow them to run any of their own collective farms, mills, factories, schools, or hospitals. Instead, those tasks went to several hundred ethnic Koreans imported from Central Asia, bilingual in Russian and Korean. Resentment towards the social dominance of Koreans from Central Asia over the Sakhalin Koreans led to tensions between the two groups. Sakhalin Koreans coined a number of disparaging terms in Korean to refer to the Koreans from Cnetral Asia.[4][16][17]

The Sakhalin government's policy towards the Sakhalin Koreans continued to shift in line with bilateral relations between North Korea and the Soviet Union. During the 1950s, North Korea demanded that the Soviets treat Sakhalin Koreans as North Korean citizens, and, through their consulate, even set up Juche study groups and other educational facilities for them (analogous to Chongryon's more successful efforts among the Zainichi Koreans). During the late 1950s, Sakhalin Koreans experienced increasing difficulty obtaining Soviet citizenship. A growing proportion chose instead to become North Korean citizens rather to than deal with the burdens of remaining stateless, which included severe restrictions on their freedom of movement and the requirement to apply for permission from the local government to travel outside of Sakhalin.[14] As of 1960, only 25 percent had been able to secure Soviet citizenship; 65 percent had declared North Korean citizenship, with the remaining 10% choosing to remain unaffiliated despite the difficulties that entailed.[18] As relations between the Soviet Union and North Korea deteriorated, the authorities acted to de-emphasize Korean language education and reduce the influence of North Korea within the community. By the early 1970s, the Russian government once again encouraged Sakhalin Koreans to apply for Soviet citizenship.[14]

Attention from the outside world

In the late 1960s and early 1970s, the situation of the Sakhalin Koreans improved as the international community began to pay much more attention to their situation. Starting in 1966, Park No Hak, a former Sakhalin Korean who had earlier received permission to leave Sakhalin and settle in Japan by virtue of his having a Japanese wife, petitioned the Japanese government a total of 23 times to discuss the issue of the Sakhalin Koreans with the Soviet government. His actions inspired 500,000 South Koreans to form an organisation to work towards the repatriation of their co-ethnics. In response, South Korea transmitted radio broadcasts targeted at the Sakhalin Koreans, in an effort to ensure them that they had not been forgotten.[19][20] At the same time, Rei Mihara, a Tokyo housewife, formed a similar pressure group in Japan, and 18 Japanese lawyers attempted to sue the Japanese government to force them to accept diplomatic and financial responsibility for the transportation of the Sakhalin Koreans and their return to South Korea.[20]

Additionally, the Soviet government finally began to permit the Sakhalin Koreans to naturalize.[14] As many as 10 percent continued to refuse both Soviet and North Korean citizenship, demanding repatriation to South Korea.[21] By 1976, only 2,000 Koreans had obtained permission to leave Sakhalin, but that year, the Sakhalin government made a public announcement that people seeking to emigrate could simply show up at the Immigration Office to file an application. Within a week, they had received more than 800 such applications, including some from North Korean citizens; that caused the North Korean embassy to complain to their Soviet counterparts about the new emigration policy. The Soviet authorities decided to refuse to issue exit visas to most the applicants, leading to the unusual case of public demonstrations by Korean families. The open dissent provoked the authorities to completely reverse their liberalizing stance towards the Sakhalin Koreans. They arrested more than 40 people protestors in November 1976, deporting them to North Korea rather than to the South as they desired. Further purges and intimidation of those seeking to emigrate followed.[19] Through to the early 1980s, locally-born Korean youth became increasingly interested in their heritage. Their Russian neighbors labeled them as traitors for wanting to know more about their ancestral land and for seeking to emigrate. The nadir of ethnic relations came after the 1983 shooting-down of Korean Air Flight 007 by the Soviet Union.[2]

Perestroika, glasnost, and the post-Soviet period

Improving relations with Japan

In 1985, Japan agreed to approve transit rights and fund the repatriation of the first generation of Sakhalin Koreans;[22] the Soviet Union also began to liberalize their emigration laws in 1987.[23] As of 2001, Japan spends US$ 1.2 million a year to fund Sakhalin Koreans' visits to Seoul. The Foreign Ministry allocated about $5 million to build a cultural centre in Sakhalin,[22] which was intended feature a library, an exhibition hall, Korean language classrooms and other facilities, but as of 2004, the project had not begun, causing protests among the Sakhalin Koreans.[24]

On April 18, 1990, Taro Nakayama, Japan's Minister for Foreign Affairs, stated:

- "Japan is deeply sorry for the tragedy in which these (Korean) people were moved to Sakhalin not of their own free will but by the design of the Japanese government and had to remain there after the conclusion of the war".[25]

Not all of the atrocities committed against the Sakhalin Koreans have been redressed. In August 1991, the descendants of the victims of the 1945 massacres filed a joint lawsuit in the Tokyo District Court seeking compensation, with the suit dismissed in July 1995.[26]

Sakhalin's trade with Japan still stands at four times that with Korea, and Japanese companies greatly outnumber their Korean on the island.[27] As a result, while members of the first generation still carry anti-Japanese sentiment, the younger generations have developed an interest in Japanese culture and have taken up the study of the Japanese language, much to the consternation of their elders.[28] On October 28, 2006, a Korean student from the Sakhalin State University placed second in the All-CIS Japanese Language Students Competition.[29]

North and South Korean influence

During the 1990s, commerce, communication, and direct flights opened up between Sakhalin and South Korea, and the two Koreas began to vie openly for influence among the Sakhalin Koreans. Television and radio programmes from both North and South Korea, as well as local programming, began airing on Sakhalin Korean Broadcasting, the only Korean television station in Russia.[30][31] North Korea negotiated with Russia for closer economic relations with Sakhalin,[32] and recently sponsored an art show in Yuzhno-Sakhalinsk.[33] They have also permitted delegations of Sakhalin Koreans to visit relatives in North Korea.[2] Scholarly studies suggest that roughly 1,000 Sakhalin Koreans have opted to repatriate to North Korea, but the rise of the South Korean economy combined with the ongoing economic crisis in the North have made that option less attractive.[1] Sakhalin Koreans have also provided assistance to refugees fleeing North Korea, who either illegally escaped across the border or escaped North Korean labour camps in Russia.[34]

South Korea and Japan jointly funded the building of a nursing home for elderly Sakhalin Koreans in Ansan, a suburb of Seoul, and under the auspices of the Korean Red Cross, 1,544 people reside and in other locations by the end of 2002, while another 14,122 traveled to South Korea on short-term visits at Japanese government expense.[35] South Korean investors, interested in the potential supply of liquefied natural gas, began to participate in the international tenders for works' contracts to develop the Sakhalin Shelf. By the year 2000, South Korean missionaries had opened several churches, and South Koreans comprised the majority of international students at the Sakhalin State University.[2] The Korean Residents' Association on Sakhalin, an ethnic representative body, is generally described as being pro-South Korean, analogous to Japan's Mindan.[24] In addition to the elderly, a few younger Koreans have also chosen to move to South Korea, either to find their roots, or for economic reasons, as wages in South Korea are as much as three times those in Sakhalin. Often viewed as foreigners by the South Korean locals, despite their previous exposure to Korean culture in Sakhalin, immigrants express discontent. As one returnee put it: "Sakhalin Koreans live in a different world than Sakhalin Russians but that world isn’t Korea".[36] Of the 1,544 Koreans who repatriated to South Korea as of 2005, nearly 10% eventually returned to Sakhalin.[1] Conversely, some foreign students from Korea studying in Sakhalin also reported difficulties in befriending local Koreans, claiming that the latter looked down on them for being foreigners.[37]

Local interethnic relations

In the late 1980s, suspicions against the Sakhalin Koreans remained. With the relaxation of internal migration controls and the collapse of the Soviet Union, Russians began moving en masse back to the mainland, leaving ethnic Koreans as a increasing percentage of the population. The Russian government became concerned that Koreans might become a majority of the island's population, and seek an autonomous republic or even independence.[38] The rise of the regional economy and the cultural assimilation of the younger generations drove more than 95% of Koreans to stay in Sakhalin or move to the Russian Far East rather than leave for South Korea, as they have come to consider Russia their home country. The Sakhalin Koreans' family connections in South Korea have benefited even those who remained on Sakhalin with easier access to South Korean business and imports. Trade with South Korea has brought the Sakhalin Koreans a better economic standing than the average resident of Sakhalin.[39] By 2004, inter-ethnic resentment between Russians and Koreans had subsided, no longer presenting a problem on Sakhalin. Sakhalin Koreans who have traveled to the mainland of Russia, or have relocated to there (a population of roughly 10,000), report that they have encountered various forms of racism.[1][40]

Among the Koreans who remain on Sakhalin, roughly 7,000 of the original generation of settlers survive, while their locally-born descendants make up the rest of the local Korean population.[30] Highly urbanized, half the Koreans live in the administrative center of Yuzhno-Sakhalinsk, where Koreans constitute nearly 12% of the population.[41] Around thirty percent of Sakhalin’s thirty thousand Koreans still resist taking Russian citizenship.[22] Unlike ethnic Russians or other local minority groups, Sakhalin Koreans enjoy exemption from conscription, but calls for that exemption's termination have increased.[42]

Culture

Personal and family names

| Korean surnames in Romanization/Cyrillization |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Korean (RR) |

Spelling (Russia) |

Spelling (USA) |

|||

| 강/姜 (Kang) | Кан (Kan) | Kang | |||

| 김/金 (Gim) | Ким (Kim) | Kim | |||

| 문/文 (Mun) | Мун (Mun) | Moon | |||

| 박/朴 (Bak) | Пак (Pak) | Park | |||

| 신/申 (Sin) | Шин (Shin) | Shin | |||

| 한/韓 (Han) | Хан (Khan) | Han | |||

| 최/崔 (Choe) | Цой (Tsoy) | Choi | |||

| 양/梁 (Yang) | Ян (Yan) | Yang | |||

- See also List of Korean family names and Cyrillization of Korean.

Korean surnames, when Cyrillized, may be spelled slightly differently from the romanisations used in the United States resulting in common pronunciations that differ, as shown in the table at right. Furthermore, Korean naming practices and Russian naming practices conflict in several important ways.[43] While most members of the older generations of Sakhalin Koreans use Korean names, members of the younger generations favor their Russian names. With the increasing exposure to South Korean pop culture, some younger Koreans have named their children after characters in Korean television dramas.[28] The use of patronymics has been scarce.

In addition to Korean names, the oldest generation of Sakhalin Koreans often register under Japanese names which they adopted during the imposition of the sōshi-kaimei policy of the Japanese colonial era. After the Soviet invasion, the Sakhalin authorities conducted name registration for the local Koreans on the basis of the Japanese identity documents issued by the old Karafuto government. As of 2006, the Russian government uniformly refused requests for re-registration under Korean names[28]

Language

Due to their greater proportion of population density, and the expectation that they may one day return to Korea, the Sakhalin Koreans have kept something of a sojourner mentality rather than a settler mentality. That has influenced their relation to the surrounding society. To this day, they tend to speak much better Korean than those deported to Central Asia.[34] A weekly Korean language newspaper, the Saegoryeo Shinmun (새고려 신문), has been published since 1949, while Sakhalin Korean Broadcasting began operation in 1956.[28] Korean-language television programmes broadcast locally, but typically with Russian subtitles.[44] Additionally, during the Soviet era, the Russian government often hired Sakhalin Koreans as announcers and writers for official media aimed at the Koryo-saram in Central Asia. Unlike the Koryo-saram, the spoken Korean of Sakhalin relates closely to Hamgyŏng dialect or Koryo-mar, deriving from Jeolla and Gyeongsang dialects. As a consequence of the Cold War, during which South Korea had no relations with the Soviet Union, the Sakhalin Koreans used North Korea Korean-language instructional materials, or developed domestically, until the 1980s. Oddly enough, as a result, Sakhalin Koreans' writing, like that of Koryo-saram, follows the North Korean standard, but their spoken Korean in radio broadcasts has come to resemble the Seoul dialect of South Korea.[45]

Religion

Since the collapse of the Soviet Union, religious activities among the Sakhalin Koreans has experienced significant growth, scholarly articles noting the increase in the establishment of churches as early as 1990.[46] Christian hymns have become popular, supplementing the more typical Russian, Western, and Korean pop music.[47] The Saegoryeo Shinmun regularly publishes sermons written by the popular South Korean pastor Jaerock Lee.[48] Korean churches also broadcast religious content through Sakhalin Korean Broadcasting; a Baptist church run by ethnic Koreans sponsors a journalist there.[49] Government authorities subject large-scale religious events to restriction: in June 1998 the local Russian Orthodox Church and the regional administration of Sakhalin successfully pressured Korean Presbyterian missionaries to cancel a conference of more than 100 Presbyterian and other Protestant missionaries from around the former Soviet Union.[50]

Music

In one survey, a third of the Sakhalin Korean population expressed a preference for traditional Korean music, a far higher proportion than in any other ethnic Korean community surveyed. Despite their better knowledge of Korean language, the same survey showed Korean pop music less widespread among Sakhalin Koreans than among ethnic Koreans in Kazakhstan, measuring about the same level of popularity as in Uzbekistan. Sakhalin Koreans also reported listening to Western popular and classical music at much lower rates than Koreans in the rest of the former Soviet Union.[47] Study of traditional Korean musical instruments has also been gaining popularity across all generations. The Ethnos Arts School, established in 1991 in Yuzhno-Sakhalinsk, teached children's' classes in traditional Korean dance, piano, sight singing, and the gayageum, a zither-like instrument supposedly invented around the time of the Gaya confederacy.[51]

Prominent Sakhalin Koreans

- Park Hae Yong, head of the Korean Residents' Association on Sakhalin[24]

- Kim Chun Ja, editor in chief of Sakhalin Korean Broadcasting[31]

- Lee Hoesung, Zainichi Korean author, born in Karafuto and later repatriated to Japan

See also

- South Korea-Russia relations

- Chinese people in Russia

- Japanese people in Russia

- Russians in Korea

Notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 Lee, Jeanyoung. "Ethnic Korean Migration in Northeast Asia". Kyunghee University. Retrieved 2006-11-27.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 "22 Koreans to be repatriated from Sakhalin", The Vladivostok News, 2004-03-30. Retrieved 2006-11-26.

- ↑ (Korean) Yi Jeong-jae. "사할린 한인의 종교와 신앙 및 의례: 유즈노사할린스크의 경우를 중심으로 (Religion, Faith, and Ceremonies of Sakhalin Koreans: Focusing on the case of Yuzhno-Sakhalinsk)". 실천민속학회. Retrieved 2007-01-21.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Byung-yool Ban. Koreans in Russia: Historical Perspective. 2004-09-22 [1]. Korea Times. accessdate 2006-11-20

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 (Japanese) Masafumi Miki. 戦間期樺太における朝鮮人社会の形成―『在日』朝鮮人史研究の空間性をめぐって (The formation of the Korean community in inter-war Karafuto) 社会経済史学 (Socio-economic History) 68 (2) Socio-Economic History Society, Waseda University.

- ↑ (Russian) Kim, German Nikolaevich 2004-12-09. accessdate 2006-11-26. [2]. Al-Farabi University. Kazakhstan Корейцы на Сахалине (Koreans in Sakhalin).

- ↑ Tessa Morris-Suzuki. Northern Lights: The Making and Unmaking of Karafuto Identity. Journal of Asian Studies 60 (3)(August 2001): 645-671 [3]. accessdate 2006-11-27. 10.2307/2700105

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Jin-woo Lee. 3,100 Sakhalin Koreans yearn to return home. The Korea Times 2005-02-18. accessdate 2006-11-26 [4].

- ↑ Sakhalin Koreans celebrate 60th anniversary of liberation from Japanese bondage. [5]. The Sakhalin Times 2005-08-26 accessdate 2006-11-27

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 (Japanese) Gil-seong Choe. 樺太における日本人の朝鮮人虐殺 (The Japanese Massacre of Koreans in Karafuto) 世界法史の単一性と複数性 (Unity and complexity of international legal history), (Miraisha, 2005), 289-296

- ↑ (Japanese) [6] サハリンレポートによる記事 accessdate 2006-11-27 Has photos.

- ↑ (Japanese) Eidai Hayashi. 証言・樺太(サハリン)朝鮮人虐殺事件 (Testimony: The Massacre of Karafuto/Sakhalin Koreans). 1992 Fubaisha

- ↑ Task Force Russia—Biweekly Report 19, December 1982 -January 8, 1993 (12th Report) U.S.-Russian Joint Delegation on POWs/MIAs 1993-01-08 accessdate 2007-02-21

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 14.2 14.3 Andrei Lankov. Stateless in Sakhalin. The Korea Times 2006-01-05. accessdate 2006-11-26 [7]

- ↑ Japan refused to help Koreans leave Sakhalin. 2000-12-19 Kyodo News agency accessdate 2006-11-27[8]

- ↑ German Kim and Valery Khan, Актуальные проблемы корейской диаспоры в Центральной Азии (Important problems of the Korean diaspora in Central Asia). Kazakh State University 2001 accessdate 2007-04-27

- ↑ Hae-kyung Um, K. Schulze, M. Stokes and C. Campbell, (eds). "The Korean diaspora in Uzbekistan and Kazakhstan: social change, identity and music-making." in Nationalism, minorities and diasporas: identities and rights in the Middle East. (London: Tauris, 1996), 217-232

- ↑ Miki Ishikida. Toward Peace: War Responsibility, Postwar Compensation, and Peace Movements and Education in Japan. (Center for US-Japan Comparative Social Studies, 2005)

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 (Japanese) Hyeong-ju Pak. サハリンからのレポート―棄てられた朝鮮人の歴史と証言 (The Report From Sakhalin: History and Testimony of Discarded Koreans), January 1991. Ochanomizu Shobo

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 The Forsaken People. 1976-01-12 accessdate 2006-11-27 Time Magazine[http://www.time.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,913836,00.html}}

- ↑ John J. Stephan. Sakhalin Island: Soviet Outpost in Northeast Asia. Asian Survey 10(12) (December 1970): 1090-1100

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 22.2 "Sakhalin Koreans discuss Japan strategy", The Sakhalin Times, 2004-05-28. Retrieved 2006-11-28.

- ↑ Aronson, Geoffrey (Summer, 1990). Soviet Jewish Emigration, the United States, and the Occupied Territories. Journal of Palestine Studies Vol. 19: pp. 30-45.

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 24.2 "Sakhalin's Koreans angry over delay in cultural center", Kyodo, 2000-10-02. Retrieved 2006-11-26.

- ↑ (Japanese) 第118回国会衆議院外務委員会議録3号 (118th National Diet Session Lower House Committee on Foreign Affairs #3). 国会会議録検索システム (Diet Minutes Search System) (1990-04-18). Retrieved 2006-11-26. Translation in Kenichi Takagi, Rethinking Japan's Postwar Compensation: Voices of Victims. tr. by Makiko Nakano.

- ↑ Postwar Compensation Cases in Japan. Center for Research and Documentation on Japan's War Responsibility. Retrieved 2006-11-29.

- ↑ Economy Committee of Sakhalin (2004). Investment Climate. Press release. Retrieved on 2006-11-28.

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 28.2 28.3 Baek, Il-hyun, "Scattered Koreans turn homeward", Joongang Daily, 2005-09-14. Retrieved 2006-11-27.

- ↑ (Russian) Жюри всероссийского конкурса японского языка присудило студентке СахГУ второе место. Sakhalin State University (2006). Retrieved 2007-01-24.

- ↑ 30.0 30.1 Jones, Lucy, "Forgotten Prisoners", The Vladivostok News, 1997-12-30. Retrieved 2006-11-26.

- ↑ 31.0 31.1 Kim, Hyun, "Wave of dramas from homeland uplifts Sakhalin Koreans", Yonhap News, 2005-07-08. Retrieved 2006-11-26.

- ↑ "North Korea calls for stronger relations with Sakhalin", ITAR-TASS, 2006-11-23. Retrieved 2006-11-26.

- ↑ "North Korean Art Exhibition being held in Sakhalin", The Sakhalin Times. Retrieved 2006-11-26.

- ↑ 34.0 34.1 Yoon, Yeo-sang. "Situation and Protection of North Korean Refugees in Russia". Korea Political Development Research Center. Retrieved 2006-11-27.

- ↑ The Republic of Korea National Red Cross. Inter-Korean Affairs: Family Reunions. Press release. Retrieved on 2006-11-26.

- ↑ "Transplanted Sakhaliner", The Sakhalin Times, 2004-07-02. Retrieved 2006-11-27.

- ↑ Yong, Kyeong Roo, "Sakhalin's Three Sets of Koreans", 2005-06-06. Retrieved 2006-11-28.

- ↑ Stroev, Anatoly, "Помни имя своё", Литературная газета (Literaturnaya Gazeta), December 2005. Retrieved 2006-11-29.

- ↑ "A battle for workers in Russia's Far East", International Herald Tribune, 2002-09-02. Retrieved 2005-07-07.

- ↑ "Sakhalin's Koreans", The Sakhalin Times, 2004-01-20. Retrieved 2006-11-27.

- ↑ "Ansan Delegation visits Sakhalin", The Sakhalin Times, 2004-07-30. Retrieved 2006-11-28.

- ↑ "Koreans make Sakhalin multi-cultural", The Sakhalin Times, 2005-10-25. Retrieved 2006-11-28.

- ↑ German Nikolaevich Kim, and Steven Sunwoo Lee (translator) "Names of Koryo-saram." Al-Farabi University.[9]. accessdate 2006-11-28

- ↑ "Autumn Fairy Tale" Sparks Hallyu Wave in Sakhalin Korean Broadcasting System. 2005-03-10, accessdate 2007-01-22

- ↑ (Russian)German Nikolaevich Kim. О родном языке корейцев Казахстана (About the native language of Koreans in Kazakhstan) [10]. Al-Farabi University 2004-12-09. accessdate 2006-11-26

- ↑ (Korean) Yong-guk Kim. 사할린에 한인교회 설립 (Establishment of Korean churches on Sakhalin). [11] 3-9 July 1990. accessdate 2007-01-22 North Korea ISSN 1227-8378

- ↑ 47.0 47.1 Hae-kyung Um. Listening patterns and identity of the Korean diaspora in the former USSR. British Journal of Ethnomusicology 9 (2) (2000): 127-144 [12].

- ↑ (Korean) [13]. Manmin Joong Ang Church. 2006 accessdate 2007-01-22 교회 연혁

- ↑ Geraldine Fagan. [14] Forum 18 RUSSIA: Local restrictions on mission in Sakhalin region. 2004-06-01, accessdate 2007-01-22

- ↑ U.S. Department of State. Annual Report on International Religious Freedom for 1999: Russia 1999.[15]. accessdate 2007-01-22

- ↑ (Korean) Chung, Sang-yeong, "사할린 고려인 학생들, 국악사랑에 흠뻑 취한 사흘: 러 사할린 에트노스예술학교 (For Sakhalin Goryeo-in, three days filled with love of Korean traditional music: Sakhalin's Ethnos Arts School)", Hankyoreh, 2005-07-25. Retrieved 2007-01-21.

References

ISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Brun, Michel. 1995. Incident at Sakhalin the true mission of KAL flight 007. New York: Four Walls Eight Windows. ISBN 9780585291826

- Chee, Choung Il. 1987. "Repatriation of stateless Koreans from Sakhalin Island: legal aspects." Korea and World Affairs. 708-744. OCLC 84459086

- Chekhov, Anton Pavlovich, and Brian Reeve. 2007. Sakhalin Island. Oxford: Oneworld Classics. ISBN 9781847490391

- Choi, Ki-young, 2004. Overseas Migration and Repatriation of Koreans - Forced Migration of Koreans to Sakhalin and Their Repatriation. Korea Journal 44 (4): 111. OCLC 98049935

- Kim-Gibson, Dai Sil. 1995. [Ichyechin salamtul] A Forgotten people: the Sakhalin Koreans. San Francisco, CA: Distributed by NAATA Distribution. OCLC 41668981

- Plaintiff's Attorneys of the Litigation for the Korean Refugees in Sakhalin. 1976. For the salvation of the Korean refugees in Sakhalin. Tokyo: Office of plaintiff's Attorneys. OCLC 5419497

- Um, Hae-kyung, "The Korean diaspora in Uzbekistan and Kazakhstan: social change, identity and music-making." in Nationalism, minorities and diasporas: identities and rights in the Middle East, edited by K. Schulze, M. Stokes and C. Campbell. London: I.B. Tauris, 1996. ISBN 1860640524, 217-232

External links

All links retrieved December 22, 2022.

- History of the Sakhalin Koreans.

- Sakhalin Arilang (YouTube Video).

| Koreans outside of Korea | |

|---|---|

| East Asia | People's Republic of China (Mainland · Hong Kong) · Republic of China (Taiwan) · Japan |

| Southeast Asia | Indonesia · Malaysia · Philippines · Singapore · Vietnam |

| Rest of Asia | Arab world · Iran · Former USSR (Central Asia · Sakhalin · North Koreans) |

| Outside of Asia | Africa · Australia · Canada · France · Germany · United States |

| Dialects | Koryo-mar · Zainichi Korean language |

| Other topics | Adoptees · Koreatowns · North Korean defectors |

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

- Sakhalin Koreans history

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

- History of "Sakhalin Koreans"

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.

↧ Download as ZWI file | Last modified: 02/04/2023 00:00:21 | 39 views

☰ Source: https://www.newworldencyclopedia.org/entry/Sakhalin_Koreans | License: CC BY-SA 3.0

ZWI signed:

ZWI signed: KSF

KSF