George Orwell

From Nwe

From Nwe

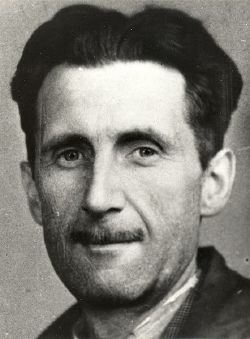

| George Orwell | |

Orwell's press card portrait, 1943

|

|

| Born | Eric Arthur Blair June 25, 1903 Motihari, Bengal Presidency, British India |

|---|---|

| Died | January 21 1950 (aged 46) London, England |

| Resting place | All Saints' Church, Sutton Courtenay, England |

| Alma mater | Eton College |

| Occupation | Novelist, essayist, journalist, literary critic |

| Political party | Independent Labour Party (from 1938) |

| Spouse(s) | Eileen O'Shaughnessy (m. 1936; died 1945) Sonia Brownell (m. 1949) |

| Children | Richard Blair |

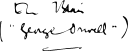

| Signature | |

Eric Arthur Blair (June 25, 1903 – January 21, 1950), better known by the pen name George Orwell, was a British author and journalist. Noted as a political and cultural commentator, as well as an accomplished novelist, Orwell is among the most widely admired English-language essayists of the twentieth century. He is best known for two novels written toward the end of his life: the political allegory Animal Farm and the dystopian novel Nineteen Eighty-Four. Orwell was a committed socialist, who remained committed to democratic socialism even after he became disenchanted with both the horrors of Stalinist Russia and the willingness of some socialists to excuse those horrors in the name of socialism.

Life

Eric Blair was born on June 25, 1903, to an Anglo-Indian family in Motihari, Bihar, in India, during the period when India was part of the British Empire under the British Raj. Blair's father, Richard Walmesley Blair, worked for the opium department of the Civil Service. His mother, Ida, brought him to Britain at the age of one. He did not see his father again until 1907, when Richard visited England for three months before leaving again. Eric had an older sister named Marjorie, and a younger sister named Avril. He would later describe his family's background as "lower-upper-middle class."

Education

At the age of six, Blair was sent to a small Anglican parish school in Henley-on-Thames, which his sister had attended before him. He never wrote recollections of his time there, but he must have impressed the teachers very favorably. Two years later he was recommended to the headmaster of one of the most successful preparatory schools in England at the time: St. Cyprian's School, in Eastbourne, Sussex. Blair attended St. Cyprian's on a scholarship that allowed his parents to pay only half of the usual fees. Many years later, he would recall his time at St. Cyprian's with biting resentment in the essay "Such, Such Were the Joys," describing the stifling limits placed on his development by the warden. "They [the officials] were my benefactors," writes Orwell, "sacrificing financial gain in order that the cleverest might bring academic accolades to the school." "Our brains were a gold-mine in which he [the warden] had sunk money, and the dividends must be squeezed out of us." However, in his time at St. Cyprians, Orwell successfully earned scholarships to both Wellington College and Eton College.

After a term at Wellington, Eric moved to Eton, where he was a King's Scholar from 1917 to 1921. Later in life he wrote that he had been "relatively happy" at Eton, which allowed its students considerable independence, but also that he ceased doing serious work after arriving there. Reports of his academic performance at Eton vary; some assert that he was a poor student, while others claim the contrary. He was clearly disliked by some of his teachers, who resented what they perceived as his disrespect for their authority. During his time at the school, Eric made lifetime friendships with a number of future British intellectuals such as Cyril Connolly, the future editor of the Horizon magazine, in which many of Orwell's most famous essays were originally published.

Burma and early writing career

After finishing his studies at Eton and having neither the prospect of gaining a university scholarship nor sufficient family means to pay his tuition, Eric joined the Indian Imperial Police in Burma. He resigned and returned to England in 1927 having grown to hate imperialism, as he demonstrated in his novel Burmese Days (1934), and in essays such as "A Hanging," and "Shooting an Elephant." He lived for several years in poverty, sometimes homeless, sometimes doing itinerant work, experiences that he narrated in Down and Out in Paris and London, his first major work. He eventually found work as a schoolteacher. His experiences as a schoolteacher formed part of his novel A Clergyman's Daughter. Ill health forced him to give teaching up to work part-time as an assistant in a second-hand bookshop in Hampstead, an experience later partially recounted in the novel Keep the Aspidistra Flying.

Eric Blair became George Orwell in 1933, while the author was writing for the New Adelphi, and living in Hayes, Middlesex, working as a schoolmaster. He adopted a pen name in order not to embarrass his parents with Down and Out in Paris and London. He considered such possible pseudonyms as "Kenneth Miles" and "H. Lewis Allways" before settling on George Orwell. Why he did so is unknown. He knew and liked the River Orwell in Suffolk and seems to have found the plainness of the first name George attractive.

Between 1936 and 1945, Orwell was married to Eileen O'Shaughnessy, with whom he adopted a son, Richard Horatio Blair (born May 1944). She died in 1945 during an operation.

Spanish Civil War

In December 1936, Orwell went to Spain to fight for the Republican side in the Spanish Civil War against Francisco Franco's Nationalist uprising. He went as part of the Independent Labour Party contingent, a group of some 25 Britons who joined the militia of the Workers' Party of Marxist Unification (POUM), a revolutionary socialist party with which the ILP was allied. The POUM, along with the radical wing of the anarcho-syndicalist CNT (the dominant force on the left in Catalonia), believed that Franco could be defeated only if the working class in the Republic overthrew capitalism—a position fundamentally at odds with that of the Spanish Communist Party and its allies, which (backed by Soviet arms and aid) argued for a coalition with bourgeois parties to defeat the Nationalists.

By his own admission, Orwell joined the POUM rather than the communist-run International Brigades by chance—but his experiences, in particular his witnessing the communist suppression of the POUM in May 1937, made him a fervent supporter of the POUM line and turned him into a lifelong anti-Stalinist. During his military service, Orwell was shot through the neck and was lucky to survive. His book Homage to Catalonia describes his experiences in Spain. To recuperate from his injuries, he spent six months in Morocco, described in his essay Marrakech[1]

World War II years

Orwell began supporting himself by writing book reviews for the New English Weekly until 1940. During World War II he was a member of the Home Guard, for which he received the Defence medal. In 1941 Orwell began work for the BBC Eastern Service, mostly working on programs to gain Indian and East Asian support for Britain's war efforts. He was well aware that he was shaping propaganda, and wrote that he felt like "an orange that's been trodden on by a very dirty boot." Despite the good pay, he resigned in 1943 to become literary editor of Tribune, the left-wing weekly then edited by Aneurin Bevan and Jon Kimche. Orwell contributed a regular column titled "As I Please."

In 1944, Orwell finished his anti-Stalinist allegory Animal Farm, which was published the following year, and met with great critical and popular success. The royalties from Animal Farm provided Orwell with a comfortable income for the first time in his adult life. While Animal Farm was at the printer, Orwell left Tribune to become (briefly) a war correspondent for Observer. He was a close friend of the Observer's editor/owner, David Astor, and his ideas had a strong influence on Astor's editorial policies. (Astor, who died in 2001, is buried in the grave next to Orwell.)

Post-World War II and final years

Orwell returned from Europe in spring 1945, and for the next three years mixed journalistic work—mainly for Tribune, the Observer, and the Manchester Evening News, as well as contributions to many small-circulation political and literary magazines—with writing his best-known work, the dystopian Nineteen Eighty-Four, which was published in 1949.[2]

He wrote much of the novel while living in a remote farmhouse on the island of Jura, off the coast of Scotland, to which he moved in 1946 despite increasingly bad health.

In 1949, Orwell was approached by a friend, Celia Kirwan, who had just started working for a Foreign Office unit, the Information Research Department, set up by the Labour government to publish pro-democratic and anti-communist propaganda. He gave her a list of 37 writers and artists he considered to be unsuitable as IRD authors because of their pro-communist leanings. The list, not published until 2003, consists mainly of journalists (among them the editor of the New Statesman, Kingsley Martin) but also includes the actors Michael Redgrave and Charlie Chaplin. Orwell's motives for handing over the list are unclear, but the most likely explanation is the simplest: that he was helping out a friend in a cause—anti-Stalinism—that they both supported. There is no indication that Orwell ever abandoned the democratic socialism that he consistently promoted in his later writings—or that he believed the writers he named should be suppressed. Orwell's list was also accurate: the people on it had all, at one time or another, made pro-Soviet or pro-communist public pronouncements.

In October 1949, shortly before his death, he married Sonia Brownell. Orwell died in London at the age of 46 from tuberculosis, which he had probably contracted during the period described in Down and Out in Paris and London. He was in and out of hospitals for the last three years of his life. Having requested burial in accordance with the Anglican rite, he was interred in All Saints' Churchyard, Sutton Courtenay, Oxfordshire with the simple epitaph: Here lies Eric Arthur Blair, born June 25th, 1903, died January 21st, 1950.

Orwell's adopted son, Richard Horatio Blair, was raised by an aunt after his father's death. He maintains a low public profile, though he has occasionally given interviews about the few memories he has of his father. Blair worked for many years as an agricultural agent for the British government, and had no interest in writing.

Political views

Orwell's political views changed over time, but there can be no doubt that he was a man of the left throughout his life as a writer. His time in Burma made him a staunch opponent of imperialism and his experience of poverty while researching Down and Out in Paris and London and The Road to Wigan Pier turned him into a socialist. In 1946, he wrote: "Every line of serious work that I have written since 1936 has been written, directly or indirectly, against totalitarianism and for democratic Socialism, as I understand it."[3]

It was Spain, however, that played the most important part in defining his socialism. Having witnessed at firsthand the suppression of the revolutionary left by the communists, Orwell returned from Catalonia a staunch anti-Stalinist and joined the Independent Labour Party.

At the time, like most other left-wingers in Britain, he was still opposed to rearmament against Hitlerite Germany—but after the Molotov-Ribbentrop pact and the outbreak of World War II, he changed his mind. He left the ILP over its pacifism and adopted a political position of "revolutionary patriotism." He supported the war effort but detected (wrongly as it turned out) a mood that would lead to a revolutionary socialist movement among the British people. "We are in a strange period of history in which a revolutionary has to be a patriot and a patriot has to be a revolutionary," he wrote in Tribune, the Labour left's weekly, in December 1940.

By 1943, his thinking had moved on. He joined the staff of Tribune as literary editor, and from then until his death was a left-wing (though hardly orthodox) democratic socialist. He canvassed for the Labour Party in the 1945 general election and was broadly supportive of its actions in office, though he was sharply critical of its timidity on certain key questions and was also harshly critical of the pro-Sovietism of many Labour left-wingers.

Although he was never either a Trotskyist or an anarchist, he was strongly influenced by the Trotskyist and anarchist critiques of the Soviet regime and by the anarchists' emphasis on individual freedom. Many of his closest friends in the mid-1940s were part of the small anarchist scene in London.

In his last years, Orwell was, unlike several of his comrades around Tribune, a fierce opponent of the creation of the state of Israel. He was also an early proponent of a federal Europe.

Work

During most of his career, Orwell was best known for his journalism, in books of reportage such as Homage to Catalonia (describing his experiences during the Spanish Civil War), Down and Out in Paris and London (describing a period of poverty in those cities), and The Road to Wigan Pier, which described the living conditions of poor miners in northern England. According to Newsweek, Orwell "was the finest of his day and the foremost architect of the English essay since Hazlitt."[4]

Contemporary readers are more often introduced to Orwell as a novelist, particularly through his enormously successful titles Animal Farm and Nineteen Eighty-Four. The former is an allegory of the corruption of the socialist ideals of the Russian Revolution by Stalinism, and the latter is Orwell's prophetic vision of the results of totalitarianism.

Animal Farm

Animal Farm is the story of the formation of a commune among a group of intelligent farm-animals, first published in England on August 17. 1945.[5] The idea for forming a socialistic commune is first put forward by the pigs Napoleon and Snowball. (Each of the different kinds of animal in the novel is symbolic for different demographic groups: the naive but hard-working horse represents the ignorant lower-classes; the conniving pigs represent the educated upper crust.) The pigs suggest that they need to overthrow their oppressive master—the human proprietor of the farm—so that they can be liberated, living and working together as perfect equals and fulfilling their maximum potential.

At first, following a brief revolution, the animal-commune runs swimmingly. As the novel progresses, however, the pigs (who, as the most intelligent creatures on the farm tend to be the ones to whom the others defer) become corrupt and abandon their utopian ideals for their own selfish ends. This is best epitomized by the transformation of "All animals are equal," the motto on which the commune was founded, into "All animals are equal; but some animals are more equal than others." By the novel's end, the commune has become an outright dictatorship, the farm itself is in tatters, and after the pigs are at last overthrown the surviving animals are left to squat amongst their own ruins.

Nineteen Eighty-Four

1984, published in 1948, is the story of Winston Smith living in the totalitarian super-state of Oceania. Oceania is Orwell's vision of a future word dominated by Stalinism. The country itself is massive, spanning roughly a third of the globe. The other two-thirds are controlled by Eurasia and East Asia, two equally oppressive (and possibly fictional) super-states, with which Oceania is purportedly in a state of perpetual war. In Oceania, every aspect of life is subject to severe and often surreal regulation and control. In every room of every house there is a telescreen, a sort of TV-in-reverse, which allows the ministers of Oceania's Thought Police to monitor the daily lives of every one of its citizens. If a citizen such as Winston Smith were to so much as try and obscure the telescreen with some furniture to obtain even the slightest degree of privacy the Thought Police would descend upon him in a matter of moments.

The story of the novel is that of Winston Smith's rebellion against the suffocating oppression of his world, his brief escape, and his ultimate capture at the hands of the Thought Police. Smith is a clerk for the Ministry of Truth, Oceania's perverse department of archives and propaganda. His job is to write and rewrite the history of Oceania as The Party sees fit, using "Newspeak" a simplified and obfuscatory language designed to make independent thought impossible. He dreams of joining the fabled Brotherhood—a shadowy band of rebels and guerillas who continue to fight against the state. Briefly, he gets his chance, meeting a young woman named Julia who sympathizes with him in the cause, and with whom he falls in love. Eventually the two meet O'Brien, a man who claims to have connections to the Brotherhood and the ongoing cause of liberation, but who is in fact an agent of The Party. Apprehended by O'Brien's men, Winston and Julia are shipped to the Ministry of Love—Oceania's ministry of torture—where Winston, under the pressure of intense interrogation, betrays Julia's life and is reduced to a hobbling wreck of a man.

Literary influences

Orwell claimed that his writing style was most similar to that of W. Somerset Maugham. In his literary essays, he also strongly praised the works of Jack London, especially his book The Road. Orwell's descent into the lives of the poor, in The Road to Wigan Pier, strongly resembles that of Jack London's The People of the Abyss, in which London disguises himself as a poverty-stricken American sailor in order to investigate the lives of the poor in London. In his literary essays, George Orwell also praised Charles Dickens and Herman Melville. Another of his favorite authors was Jonathan Swift, and, in particular, his book Gulliver's Travels.

Books

- Fiction

- Burmese Days (1934)

- A Clergyman's Daughter (1935)

- Keep the Aspidistra Flying (1936)

- Coming Up for Air (1939)

- Animal Farm (1945)

- Nineteen Eighty-Four (1949)

- Non-fiction

- Down and Out in Paris and London (1933)

- The Road to Wigan Pier (1937)

- Homage to Catalonia (1938)

Essays

- "A Hanging" (1931)

- "Shooting an Elephant" (1936)

- "Charles Dickens (essay)|Charles Dickens" (1939)

- "Boys' Weeklies" (1940)

- "Inside the Whale" (1940)

- "Wells, Hitler and the World State" (1941)

- "The Art of Donald McGill" (1941)

- The Lion and The Unicorn: Socialism and the English Genius (1941)

- "Looking Back on the Spanish War" (1943)

- "W. B. Yeats (essay)|W. B. Yeats" (1943)

- "Benefit of Clergy: Some notes on Salvador Dali" (1944)

- "Arthur Koestler (essay)|Arthur Koestler" (1944)

- "Notes on Nationalism" (1945)

- "How the Poor Die" (1946)

- "Politics vs. Literature: An Examination of Gulliver's Travels" (1946)

- "Politics and the English Language" (1946)

- "Second Thoughts on James Burnham" (1946)

- "Decline of the English Murder" (1946)

- "Some Thoughts on the Common Toad" (1946)

- "A Good Word for the Vicar of Bray" (1946)

- "In Defence of P. G. Wodehouse" (1946)

- "Why I Write" (1946)

- "The Prevention of Literature" (1946)

- "Such, Such Were the Joys" (1946)

- "Lear, Tolstoy and the Fool" (1947)

- "Reflections on Gandhi" (1949)

- "Bookshop Memories" (1936)

- "The Moon Under Water" (1946)

Poems

- Romance (1925)

- A Little Poem (1936)

Notes

- ↑ George Orwell, Marrakech. Retrieved October 31, 2022.

- ↑ George Orwell, Nineteen Eighty-Four (London, UK: Secker and Warburg, 1949, ISBN 978-0452284234).

- ↑ George Orwell, Why I Write. Retrieved October 31, 2022.

- ↑ George Orwell (1903 – 1950) Biblio. Retrieved October 31, 2022.

- ↑ George Orwell, Animal Farm: The Original 1945 Edition with Notes and Study Guide (Belin Education, 2022, ISBN 979-1035810306).

References

ISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Bowker, Gordon. George Orwell. Little Brown, 2003. ISBN 0316861154

- Crick, Bernard. George Orwell: A Life. Penguin, 1982. ISBN 0140058567

- Hitchens, Christopher. Why Orwell Matters. Basic Books, 2003. ISBN 0465030491

- Larkin, Emma. Finding George Orwell in Burma. New York: Penguin Group, 2005. ISBN 1594200521

- Newsinger, John. Orwell's Politics. Macmillan, 1999. ASIN 0333682874

- Shelden, Michael. Orwell: The Authorized Biography. HarperCollins, 1991. ISBN 0060167092

- Taylor, D. J. Orwell: The Life. Henry Holt and Company, 2003. ISBN 0805074732

- West, W. J. The Larger Evils. Edinburgh: Canongate Press, 1992. ISBN 0862413826

External links

All links retrieved October 31, 2022.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.

↧ Download as ZWI file | Last modified: 02/04/2023 00:26:40 | 29 views

☰ Source: https://www.newworldencyclopedia.org/entry/George_Orwell | License: CC BY-SA 3.0

ZWI signed:

ZWI signed:

KSF

KSF