Moons Of Saturn

From Handwiki

From Handwiki Template:Featured list is only for Wikipedia:Featured lists.

.jpg)

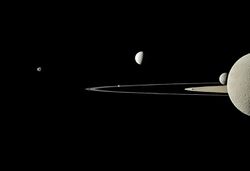

The moons of Saturn are numerous and diverse, ranging from tiny moonlets only tens of meters across to the enormous Titan, which is larger than the planet Mercury. There are 146 moons with confirmed orbits, the most of any planet in the solar system.[1][lower-alpha 1] This number does not include the many thousands of moonlets embedded within Saturn's dense rings, nor hundreds of possible kilometer-sized distant moons that were seen through telescopes but not recaptured.[3][4][5] Seven Saturnian moons are large enough to have collapsed into a relaxed, ellipsoidal shape, though only one or two of those, Titan and possibly Rhea, are currently in hydrostatic equilibrium. Three moons are particularly notable. Titan is the second-largest moon in the Solar System (after Jupiter's Ganymede), with a nitrogen-rich Earth-like atmosphere and a landscape featuring river networks and hydrocarbon lakes.[6] Enceladus emits jets of ice from its south-polar region and is covered in a deep layer of snow.[7] Iapetus has contrasting black and white hemispheres as well as an extensive ridge of equatorial mountains among the tallest in the solar system.

Of the known moons, 24 are regular satellites; they have prograde orbits not greatly inclined to Saturn's equatorial plane[8] with the exception of Iapetus which has a prograde but highly inclined orbit,[9][10] an unusual characteristic for a regular moon. They include the seven major satellites, four small moons that exist in a trojan orbit with larger moons, and five that act as shepherd moons, of which two are mutually co-orbital. Two tiny moons orbit inside of Saturn's B and G rings. The relatively large Hyperion is locked in an orbital resonance with Titan. The remaining regular moons orbit near the outer edges of the dense A Ring and the narrow F Ring, and between the major moons Mimas and Enceladus. The regular satellites are traditionally named after Titans and Titanesses or other figures associated with the mythological Saturn.

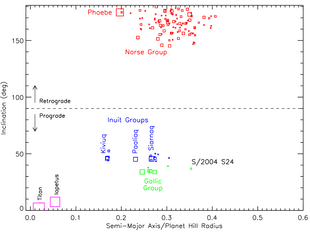

The remaining 122, with mean diameters ranging from 2 to 213 km (1 to 132 mi), are irregular satellites, whose orbits are much farther from Saturn, have high inclinations, and are mixed between prograde and retrograde. These moons are probably captured minor planets, or fragments from the collisional breakup of such bodies after they were captured, creating collisional families. Saturn is expected to have around 150 irregular satellites larger than 2.8 km (1.7 mi) in diameter, plus many hundreds more that are even smaller. The irregular satellites are classified by their orbital characteristics into the prograde Inuit and Gallic groups and the large retrograde Norse group, and their names are chosen from the corresponding mythologies (with the Gallic group corresponding to Celtic mythology). The sole exception is Phoebe, the ninth moon of Saturn and largest irregular one, discovered at the end of the 19th century; it is part of the Norse group but named for a Greek Titaness.

The rings of Saturn are made up of objects ranging in size from microscopic to moonlets hundreds of meters across, each in its own orbit around Saturn.[11] Thus an objectively precise number of Saturnian moons cannot be given, because there is no consensus on a boundary between the countless small anonymous objects that form Saturn's ring system and the larger objects that have been named as moons. Over 150 moonlets embedded in the rings have been detected by the disturbance they create in the surrounding ring material, though this is thought to be only a small sample of the total population of such objects.[4]

There are 83 designated moons that are still unnamed ((As of May 2023)); all but one (the designated B-ring moonlet S/2009 S 1) are irregular. (There are many other undesignated ring moonlets.) If named, most of the irregulars will receive names from Gallic, Norse and Inuit mythology based on the orbital group of which they are a member.[12][13]

Discovery

Early observations

Before the advent of telescopic photography, eight moons of Saturn were discovered by direct observation using optical telescopes. Saturn's largest moon, Titan, was discovered in 1655 by Christiaan Huygens using a 57-millimeter (2.2 in) objective lens[14] on a refracting telescope of his own design.[15] Tethys, Dione, Rhea and Iapetus (the "Sidera Lodoicea") were discovered between 1671 and 1684 by Giovanni Domenico Cassini.[16] Mimas and Enceladus were discovered in 1789 by William Herschel.[16] Hyperion was discovered in 1848 by W. C. Bond, G. P. Bond[17] and William Lassell.[18]

The use of long-exposure photographic plates made possible the discovery of additional moons. The first to be discovered in this manner, Phoebe, was found in 1899 by W. H. Pickering.[19] In 1966 the tenth satellite of Saturn was discovered by Audouin Dollfus, when the rings were observed edge-on near an equinox.[20] It was later named Janus. A few years later it was realized that all observations of 1966 could only be explained if another satellite had been present and that it had an orbit similar to that of Janus.[20] This object is now known as Epimetheus, the eleventh moon of Saturn. It shares the same orbit with Janus—the only known example of co-orbitals in the Solar System.[21] In 1980, three additional Saturnian moons were discovered from the ground and later confirmed by the Voyager probes. They are trojan moons of Dione (Helene) and Tethys (Telesto and Calypso).[21]

Observations by spacecraft

The study of the outer planets has since been revolutionized by the use of uncrewed space probes. The arrival of the Voyager spacecraft at Saturn in 1980–1981 resulted in the discovery of three additional moons – Atlas, Prometheus and Pandora, bringing the total to 17.[21] In addition, Epimetheus was confirmed as distinct from Janus. In 1990, Pan was discovered in archival Voyager images.[21]

The Cassini mission,[22] which arrived at Saturn in July 2004, initially discovered three small inner moons: Methone and Pallene between Mimas and Enceladus, and the second trojan moon of Dione – Polydeuces. It also observed three suspected but unconfirmed moons in the F Ring.[23] In November 2004 Cassini scientists announced that the structure of Saturn's rings indicates the presence of several more moons orbiting within the rings, although only one, Daphnis, had been visually confirmed at the time.[24] In 2007 Anthe was announced.[25] In 2008 it was reported that Cassini observations of a depletion of energetic electrons in Saturn's magnetosphere near Rhea might be the signature of a tenuous ring system around Saturn's second largest moon.[26] In March 2009, Aegaeon, a moonlet within the G Ring, was announced.[27] In July of the same year, S/2009 S 1, the first moonlet within the B Ring, was observed.[28] In April 2014, the possible beginning of a new moon, within the A Ring, was reported.[29] (related image)

Outer moons

Study of Saturn's moons has also been aided by advances in telescope instrumentation, primarily the introduction of digital charge-coupled devices which replaced photographic plates. For the 20th century, Phoebe stood alone among Saturn's known moons with its highly irregular orbit. Then in 2000, three dozen additional irregular moons were discovered using ground-based telescopes.[30] A survey starting in late 2000 and conducted using three medium-size telescopes found thirteen new moons orbiting Saturn at a great distance, in eccentric orbits, which are highly inclined to both the equator of Saturn and the ecliptic.[31] They are probably fragments of larger bodies captured by Saturn's gravitational pull.[30][31] In 2005, astronomers using the Mauna Kea Observatory announced the discovery of twelve more small outer moons,[32][33] in 2006, astronomers using the Subaru 8.2 m telescope reported the discovery of nine more irregular moons,[34] in April 2007, Tarqeq (S/2007 S 1) was announced and in May of the same year S/2007 S 2 and S/2007 S 3 were reported.[35] In 2019, twenty new irregular satellites of Saturn were reported, resulting in Saturn overtaking Jupiter as the planet with the most known moons for the first time since 2000.[13][3]

In 2019, researchers Edward Ashton, Brett Gladman, and Matthew Beaudoin conducted a survey of Saturn's Hill sphere using the 3.6-meter Canada–France–Hawaii Telescope and discovered about 80 new Saturnian irregular moons.[5][36] Follow-up observations of these new moons took place over 2019–2021, eventually leading to S/2019 S 1 being announced in November 2021 and an additional 62 moons being announced from 3–16 May 2023.[37][2] These discoveries brought Saturn's total number of confirmed moons up to 145, making it the first planet known to have over 100 moons.[37][38][39] Yet another moon, S/2006 S 20, was announced on 23 May 2023, bringing Saturn's total count moons to 146.[2] All of these new moons are small and faint, with diameters over 3 km (2 mi) and apparent magnitudes of 25–27.[5] The researchers found that the Saturnian irregular moon population is more abundant at smaller sizes, suggesting that they are likely fragments from a collision that occurred a few hundred million years ago. The researchers extrapolated that the true population of Saturnian irregular moons larger than 2.8 km (1.7 mi) in diameter amounts to 150±30, which is approximately three times as many Jovian irregular moons down to the same size. If this size distribution applies to even smaller diameters, Saturn would therefore intrinsically have more irregular moons than Jupiter.[5]

Naming

The modern names for Saturnian moons were suggested by John Herschel in 1847.[16] He proposed to name them after mythological figures associated with the Roman god of agriculture and harvest, Saturn (equated to the Greek Cronus).[16] In particular, the then known seven satellites were named after Titans, Titanesses and Giants—brothers and sisters of Cronus.[19] The idea was similar to Simon Marius' mythological naming scheme for the moons of Jupiter.[40]

As Saturn devoured his children, his family could not be assembled around him, so that the choice lay among his brothers and sister, the Titans and Titanesses. The name Iapetus seemed indicated by the obscurity and remoteness of the exterior satellite, Titan by the superior size of the Huyghenian, while the three female appellations [Rhea, Dione, and Tethys] class together the three intermediate Cassinian satellites. The minute interior ones seemed appropriately characterized by a return to male appellations [Enceladus and Mimas] chosen from a younger and inferior (though still superhuman) brood. ["Results of the Astronomical Observations made...at the Cape of Good Hope," p. 415]

In 1848, Lassell proposed that the eighth satellite of Saturn be named Hyperion after another Titan.[18][40] When in the 20th century the names of Titans were exhausted, the moons were named after different characters of the Greco-Roman mythology or giants from other mythologies.[41] All the irregular moons (except Phoebe, discovered about a century before the others) are named after Inuit and Gallic gods and after Norse ice giants.[42]

Some asteroids share the same names as moons of Saturn: 55 Pandora, 106 Dione, 577 Rhea, 1809 Prometheus, 1810 Epimetheus, and 4450 Pan. In addition, three more asteroids would share the names of Saturnian moons but for spelling differences made permanent by the International Astronomical Union (IAU): Calypso and asteroid 53 Kalypso; Helene and asteroid 101 Helena; and Gunnlod and asteroid 657 Gunlöd.

Physical characteristics

Saturn's satellite system is very lopsided: one moon, Titan, comprises more than 96% of the mass in orbit around the planet. The six other planemo (ellipsoidal) moons constitute roughly 4% of the mass, and the remaining small moons, together with the rings, comprise only 0.04%.[lower-alpha 2]

| Name |

Diameter (km)[43] |

Mass (kg)[44] |

Orbital radius (km)[45] |

Orbital period (days)[45] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mimas | 396 (0.12 D☾) |

4×1019 (0.0005 M☾) |

185,539 (0.48 a☾) |

0.9 (0.03 T☾) |

| Enceladus | 504 (0.14 D☾) |

1.1×1020 (0.002 M☾) |

237,948 (0.62 a☾) |

1.4 (0.05 T☾) |

| Tethys | 1,062 (0.30 D☾) |

6.2×1020 (0.008 M☾) |

294,619 (0.77 a☾) |

1.9 (0.07 T☾) |

| Dione | 1,123 (0.32 D☾) |

1.1×1021 (0.015 M☾) |

377,396 (0.98 a☾) |

2.7 (0.10 T☾) |

| Rhea | 1,527 (0.44 D☾) |

2.3×1021 (0.03 M☾) |

527,108 (1.37 a☾) |

4.5 (0.20 T☾) |

| Titan | 5,149 (1.48 D☾) (0.75 D♂) |

1.35×1023 (1.80 M☾) (0.21 M♂) |

1,221,870 (3.18 a☾) |

16 (0.60 T☾) |

| Iapetus | 1,470 (0.42 D☾) |

1.8×1021 (0.025 M☾) |

3,560,820 (9.26 a☾) |

79 (2.90 T☾) |

Orbital groups

Although the boundaries may be somewhat vague, Saturn's moons can be divided into ten groups according to their orbital characteristics. Many of them, such as Pan and Daphnis, orbit within Saturn's ring system and have orbital periods only slightly longer than the planet's rotation period.[46] The innermost moons and most regular satellites all have mean orbital inclinations ranging from less than a degree to about 1.5 degrees (except Iapetus, which has an inclination of 7.57 degrees) and small orbital eccentricities.[3] On the other hand, irregular satellites in the outermost regions of Saturn's moon system, in particular the Norse group, have orbital radii of millions of kilometers and orbital periods lasting several years. The moons of the Norse group also orbit in the opposite direction to Saturn's rotation.[42]

Inner moons

Ring moonlets

.jpg)

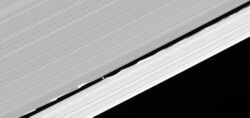

During late July 2009, a moonlet, S/2009 S 1, was discovered in the B Ring, 480 km from the outer edge of the ring, by the shadow it cast.[28] It is estimated to be 300 m in diameter. Unlike the A Ring moonlets (see below), it does not induce a 'propeller' feature, probably due to the density of the B Ring.[47]

In 2006, four tiny moonlets were found in Cassini images of the A Ring.[48] Before this discovery only two larger moons had been known within gaps in the A Ring: Pan and Daphnis. These are large enough to clear continuous gaps in the ring.[48] In contrast, a moonlet is only massive enough to clear two small—about 10 km across—partial gaps in the immediate vicinity of the moonlet itself creating a structure shaped like an airplane propeller.[49] The moonlets themselves are tiny, ranging from about 40 to 500 meters in diameter, and are too small to be seen directly.[4]

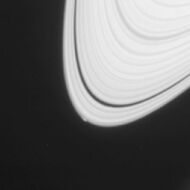

In 2007, the discovery of 150 more moonlets revealed that they (with the exception of two that have been seen outside the Encke gap) are confined to three narrow bands in the A Ring between 126,750 and 132,000 km from Saturn's center. Each band is about a thousand kilometers wide, which is less than 1% the width of Saturn's rings.[4] This region is relatively free from the disturbances caused by resonances with larger satellites,[4] although other areas of the A Ring without disturbances are apparently free of moonlets. The moonlets were probably formed from the breakup of a larger satellite.[49] It is estimated that the A Ring contains 7,000–8,000 propellers larger than 0.8 km in size and millions larger than 0.25 km.[4] In April 2014, NASA scientists reported the possible consolidation of a new moon within the A Ring, implying that Saturn's present moons may have formed in a similar process in the past when Saturn's ring system was much more massive.[29]

Similar moonlets may reside in the F Ring.[4] There, "jets" of material may be due to collisions, initiated by perturbations from the nearby small moon Prometheus, of these moonlets with the core of the F Ring. One of the largest F Ring moonlets may be the as-yet unconfirmed object S/2004 S 6. The F Ring also contains transient "fans" which are thought to result from even smaller moonlets, about 1 km in diameter, orbiting near the F Ring core.[50]

One recently discovered moon, Aegaeon, resides within the bright arc of G Ring and is trapped in the 7:6 mean-motion resonance with Mimas.[27] This means that it makes exactly seven revolutions around Saturn while Mimas makes exactly six. The moon is the largest among the population of bodies that are sources of dust in this ring.[51]

Ring shepherds

Shepherd satellites are small moons that orbit within, or just beyond, a planet's ring system. They have the effect of sculpting the rings: giving them sharp edges, and creating gaps between them. Saturn's shepherd moons are Pan (Encke gap), Daphnis (Keeler gap), Prometheus (F Ring), Janus (A Ring), and Epimetheus (A Ring).[23][27] These moons probably formed as a result of accretion of the friable ring material on preexisting denser cores. The cores with sizes from one-third to one-half the present-day moons may be themselves collisional shards formed when a parental satellite of the rings disintegrated.[46]

Janus and Epimetheus are co-orbital moons.[21] They are of similar size, with Janus being somewhat larger than Epimetheus.[46] They have orbits with less than a 100-kilometer difference in semi-major axis, close enough that they would collide if they attempted to pass each other. Instead of colliding, their gravitational interaction causes them to swap orbits every four years.[52]

Other inner moons

Other inner moons that are neither ring shepherds nor ring moonlets include Atlas and Pandora.

Inner large

The innermost large moons of Saturn orbit within its tenuous E Ring, along with three smaller moons of the Alkyonides group.

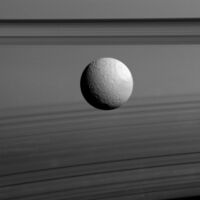

- Mimas is the smallest and least massive of the inner round moons,[44] although its mass is sufficient to alter the orbit of Methone.[52] It is noticeably ovoid-shaped, having been made shorter at the poles and longer at the equator (by about 20 km) by the effects of Saturn's gravity.[53] Mimas has a large impact crater one-third its diameter, Herschel, situated on its leading hemisphere.[54] Mimas has no known past or present geologic activity, and its surface is dominated by impact craters. The only tectonic features known are a few arcuate and linear troughs, which probably formed when Mimas was shattered by the Herschel impact.[54]

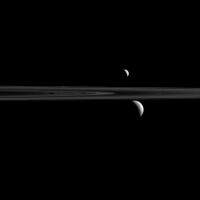

- Enceladus is one of the smallest of Saturn's moons that is spherical in shape—only Mimas is smaller[53]—yet is the only small Saturnian moon that is currently endogenously active, and the smallest known body in the Solar System that is geologically active today.[55] Its surface is morphologically diverse; it includes ancient heavily cratered terrain as well as younger smooth areas with few impact craters. Many plains on Enceladus are fractured and intersected by systems of lineaments.[55] The area around its south pole was found by Cassini to be unusually warm and cut by a system of fractures about 130 km long called "tiger stripes", some of which emit jets of water vapor and dust.[55] These jets form a large plume off its south pole, which replenishes Saturn's E ring[55] and serves as the main source of ions in the magnetosphere of Saturn.[56] The gas and dust are released with a rate of more than 100 kg/s. Enceladus may have liquid water underneath the south-polar surface.[55] The source of the energy for this cryovolcanism is thought to be a 2:1 mean-motion resonance with Dione.[55] The pure ice on the surface makes Enceladus one of the brightest known objects in the Solar System—its geometrical albedo is more than 140%.[55]

- Tethys is the third largest of Saturn's inner moons.[44] Its most prominent features are a large (400 km diameter) impact crater named Odysseus on its leading hemisphere and a vast canyon system named Ithaca Chasma extending at least 270° around Tethys.[54] The Ithaca Chasma is concentric with Odysseus, and these two features may be related. Tethys appears to have no current geological activity. A heavily cratered hilly terrain occupies the majority of its surface, while a smaller and smoother plains region lies on the hemisphere opposite to that of Odysseus.[54] The plains contain fewer craters and are apparently younger. A sharp boundary separates them from the cratered terrain. There is also a system of extensional troughs radiating away from Odysseus.[54] The density of Tethys (0.985 g/cm3) is less than that of water, indicating that it is made mainly of water ice with only a small fraction of rock.[43]

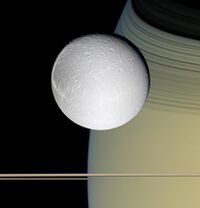

- Dione is the second-largest inner moon of Saturn. It has a higher density than the geologically dead Rhea, the largest inner moon, but lower than that of active Enceladus.[53] While the majority of Dione's surface is heavily cratered old terrain, this moon is also covered with an extensive network of troughs and lineaments, indicating that in the past it had global tectonic activity.[57] The troughs and lineaments are especially prominent on the trailing hemisphere, where several intersecting sets of fractures form what is called "wispy terrain".[57] The cratered plains have a few large impact craters reaching 250 km in diameter.[54] Smooth plains with low impact-crater counts are also present on a small fraction of its surface.[58] They were probably tectonically resurfaced relatively later in the geological history of Dione. At two locations within smooth plains strange landforms (depressions) resembling oblong impact craters have been identified, both of which lie at the centers of radiating networks of cracks and troughs;[58] these features may be cryovolcanic in origin. Dione may be geologically active even now, although on a scale much smaller than the cryovolcanism of Enceladus. This follows from Cassini magnetic measurements that show Dione is a net source of plasma in the magnetosphere of Saturn, much like Enceladus.[58]

Alkyonides

Three small moons orbit between Mimas and Enceladus: Methone, Anthe, and Pallene. Named after the Alkyonides of Greek mythology, they are some of the smallest moons in the Saturn system. Anthe and Methone have very faint ring arcs along their orbits, whereas Pallene has a faint complete ring.[59] Of these three moons, only Methone has been photographed at close range, showing it to be egg-shaped with very few or no craters.[60]

Trojan

Trojan moons are a unique feature only known from the Saturnian system. A trojan body orbits at either the leading L4 or trailing L5 Lagrange point of a much larger object, such as a large moon or planet. Tethys has two trojan moons, Telesto (leading) and Calypso (trailing), and Dione also has two, Helene (leading) and Polydeuces (trailing).[23] Helene is by far the largest trojan moon,[53] while Polydeuces is the smallest and has the most chaotic orbit.[52] These moons are coated with dusty material that has smoothed out their surfaces.[61]

Outer large

.jpg)

These moons all orbit beyond the E Ring. They are:

- Rhea is the second-largest of Saturn's moons. It is even slightly larger than Oberon, the second-largest moon of Uranus.[53] In 2005, Cassini detected a depletion of electrons in the plasma wake of Rhea, which forms when the co-rotating plasma of Saturn's magnetosphere is absorbed by the moon.[26] The depletion was hypothesized to be caused by the presence of dust-sized particles concentrated in a few faint equatorial rings.[26] Such a ring system would make Rhea the only moon in the Solar System known to have rings.[26] Subsequent targeted observations of the putative ring plane from several angles by Cassini's narrow-angle camera turned up no evidence of the expected ring material, leaving the origin of the plasma observations unresolved.[62] Otherwise Rhea has rather a typical heavily cratered surface,[54] with the exceptions of a few large Dione-type fractures (wispy terrain) on the trailing hemisphere[63] and a very faint "line" of material at the equator that may have been deposited by material deorbiting from present or former rings.[64] Rhea also has two very large impact basins on its anti-Saturnian hemisphere, which are about 400 and 500 km across.[63] The first, Tirawa, is roughly comparable to the Odysseus basin on Tethys.[54] There is also a 48 km-diameter impact crater called Inktomi[65][lower-alpha 3] at 112°W that is prominent because of an extended system of bright rays,[66] which may be one of the youngest craters on the inner moons of Saturn.[63] No evidence of any endogenic activity has been discovered on the surface of Rhea.[63]

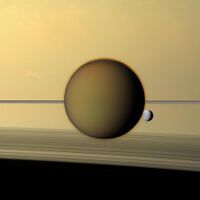

- Titan, at 5,149 km diameter, is the second largest moon in the Solar System and Saturn's largest.[67][44] Out of all the large moons, Titan is the only one with a dense (surface pressure of 1.5 atm), cold atmosphere, primarily made of nitrogen with a small fraction of methane.[68] The dense atmosphere frequently produces bright white convective clouds, especially over the south pole region.[68] On June 6, 2013, scientists at the IAA-CSIC reported the detection of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in the upper atmosphere of Titan.[69] On June 23, 2014, NASA claimed to have strong evidence that nitrogen in the atmosphere of Titan came from materials in the Oort cloud, associated with comets, and not from the materials that formed Saturn in earlier times.[70] The surface of Titan, which is difficult to observe due to persistent atmospheric haze, shows only a few impact craters and is probably very young.[68] It contains a pattern of light and dark regions, flow channels and possibly cryovolcanos.[68][71] Some dark regions are covered by longitudinal dune fields shaped by tidal winds, where sand is made of frozen water or hydrocarbons.[72] Titan is the only body in the Solar System beside Earth with bodies of liquid on its surface, in the form of methane–ethane lakes in Titan's north and south polar regions.[73] The largest lake, Kraken Mare, is larger than the Caspian Sea.[74] Like Europa and Ganymede, it is believed that Titan has a subsurface ocean made of water mixed with ammonia, which can erupt to the surface of the moon and lead to cryovolcanism.[71] On July 2, 2014, NASA reported the ocean inside Titan may be "as salty as the Earth's Dead Sea".[75][76]

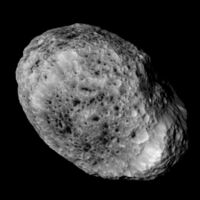

- Hyperion is Titan's nearest neighbor in the Saturn system. The two moons are locked in a 4:3 mean-motion resonance with each other, meaning that while Titan makes four revolutions around Saturn, Hyperion makes exactly three.[44] With an average diameter of about 270 km, Hyperion is smaller and lighter than Mimas.[77] It has an extremely irregular shape, and a very odd, tan-colored icy surface resembling a sponge, though its interior may be partially porous as well.[77] The average density of about 0.55 g/cm3[77] indicates that the porosity exceeds 40% even assuming it has a purely icy composition. The surface of Hyperion is covered with numerous impact craters—those with diameters 2–10 km are especially abundant.[77] It is the only moon besides the small moons of Pluto known to have a chaotic rotation, which means Hyperion has no well-defined poles or equator. While on short timescales the satellite approximately rotates around its long axis at a rate of 72–75° per day, on longer timescales its axis of rotation (spin vector) wanders chaotically across the sky.[77] This makes the rotational behavior of Hyperion essentially unpredictable.[78]

- Iapetus is the third-largest of Saturn's moons.[53] Orbiting the planet at 3.5 million km, it is by far the most distant of Saturn's large moons, and also has the largest orbital inclination, at 15.47°.[45] Iapetus has long been known for its unusual two-toned surface; its leading hemisphere is pitch-black and its trailing hemisphere is almost as bright as fresh snow.[79] Cassini images showed that the dark material is confined to a large near-equatorial area on the leading hemisphere called Cassini Regio, which extends approximately from 40°N to 40°S.[79] The pole regions of Iapetus are as bright as its trailing hemisphere. Cassini also discovered a 20 km tall equatorial ridge, which spans nearly the moon's entire equator.[79] Otherwise both dark and bright surfaces of Iapetus are old and heavily cratered. The images revealed at least four large impact basins with diameters from 380 to 550 km and numerous smaller impact craters.[79] No evidence of any endogenic activity has been discovered.[79] A clue to the origin of the dark material covering part of Iapetus's starkly dichromatic surface may have been found in 2009, when NASA's Spitzer Space Telescope discovered a vast, nearly invisible disk around Saturn, just inside the orbit of the moon Phoebe – the Phoebe ring.[80] Scientists believe that the disk originates from dust and ice particles kicked up by impacts on Phoebe. Because the disk particles, like Phoebe itself, orbit in the opposite direction to Iapetus, Iapetus collides with them as they drift in the direction of Saturn, darkening its leading hemisphere slightly.[80] Once a difference in albedo, and hence in average temperature, was established between different regions of Iapetus, a thermal runaway process of water ice sublimation from warmer regions and deposition of water vapor onto colder regions ensued. Iapetus's present two-toned appearance results from the contrast between the bright, primarily ice-coated areas and regions of dark lag, the residue left behind after the loss of surface ice.[81][82]

Irregular

Irregular moons are small satellites with large-radii, inclined, and frequently retrograde orbits, believed to have been acquired by the parent planet through a capture process. They often occur as collisional families or groups.[30] The precise size as well as albedo of the irregular moons are not known for sure because the moons are very small to be resolved by a telescope, although the latter is usually assumed to be quite low—around 6% (albedo of Phoebe) or less.[31] The irregulars generally have featureless visible and near infrared spectra dominated by water absorption bands.[30] They are neutral or moderately red in color—similar to C-type, P-type, or D-type asteroids,[42] though they are much less red than Kuiper belt objects.[30][lower-alpha 4]

Inuit

The Inuit group includes twelve prograde outer moons that are similar enough in their distances from the planet (190–300 radii of Saturn), their orbital inclinations (45–50°) and their colors that they can be considered a group.[31][42] The Inuit group is further split into three distinct subgroups at different semi-major axes, and are named after their respective largest members. Ordered by increasing semi-major axis, these subgroups are the Kiviuq group, the Paaliaq group, and the Siarnaq group.[1] The Kiviuq group includes five members: Kiviuq, Ijiraq, S/2005 S 4, S/2019 S 1, and S/2020 S 1. The Siarnaq group includes six members: Siarnaq, Tarqeq, S/2004 S 31, S/2019 S 14, S/2020 S 3, and S/2020 S 5.[83] In contrast to the Kiviuq and Siarnaq subgroups, the Paaliaq subgroup does not contain any other known members besides Paaliaq itself.[1] Of the entire Inuit group, Siarnaq is the largest member with an estimated size of about 40 km.[84]

Gallic

The Gallic group includes seven prograde outer moons that are similar enough in their distance from the planet (200–300 radii of Saturn), their orbital inclination (35–40°) and their color that they can be considered a group.[31][42] They are Albiorix, Bebhionn, Erriapus, Tarvos,[42] Saturn LX,[85] S/2007 S 8, and S/2020 S 4.[83] The largest of these moons is Albiorix with an estimated size of about 32 km.[84]

Norse

All 100 retrograde outer moons of Saturn are broadly classified into the Norse group.[31][42] They are Aegir, Angrboda, Alvaldi, Beli, Bergelmir, Bestla, Eggther, Farbauti, Fenrir, Fornjot, Geirrod, Gerd, Greip, Gridr, Gunnlod, Hati, Hyrrokkin, Jarnsaxa, Kari, Loge, Mundilfari, Narvi, Phoebe, Skathi, Skoll, Skrymir, Surtur, Suttungr, Thiazzi, Thrymr, Ymir,[42] and 69 unnamed satellites. After Phoebe, Ymir is the largest of the known retrograde irregular moons, with an estimated diameter of only 18 km.[1]

- Phoebe, at 213±1.4 km in diameter, is by far the largest of Saturn's irregular satellites.[30] It has a retrograde orbit and rotates on its axis every 9.3 hours.[86] Phoebe was the first moon of Saturn to be studied in detail by Cassini, in June 2004; during this encounter Cassini was able to map nearly 90% of the moon's surface. Phoebe has a nearly spherical shape and a relatively high density of about 1.6 g/cm3.[30] Cassini images revealed a dark surface scarred by numerous impacts—there are about 130 craters with diameters exceeding 10 km. Such impacts may have ejected fragments of Phoebe into orbit around Saturn—two of these may be S/2006 S 20 and S/2006 S 9, whose orbits are similar to Phoebe.[1][87][88] Spectroscopic measurement showed that the surface is made of water ice, carbon dioxide, phyllosilicates, organics and possibly iron-bearing minerals.[30] Phoebe is believed to be a captured centaur that originated in the Kuiper belt.[30] It also serves as a source of material for the largest known ring of Saturn, which darkens the leading hemisphere of Iapetus (see above).[80]

Outlier prograde satellites

Three prograde moons of Saturn do not definitively belong to either the Inuit or Gallic groups.[1] S/2004 S 24 and S/2006 S 12 have similar orbital inclinations as the Gallic group, but have much more distant orbits with semi-major axes of ~400 Saturn radii and ~340 Saturn radii, respectively.[83][13][1] Whether S/2019 S 6 is in the Gallic group or Inuit group is disputed.[lower-alpha 5]

List

Confirmed

The Saturnian moons are listed here by orbital period (or semi-major axis), from shortest to longest. Moons massive enough for their surfaces to have collapsed into a spheroid are highlighted in bold and marked with a blue background, while the irregular moons are listed in red, orange, green, and gray background. The orbits and mean distances of the irregular moons are strongly variable over short timescales due to frequent planetary and solar perturbations, so the orbital elements of irregular moons listed here are averaged over a 5,000-year numerical integration by the Jet Propulsion Laboratory. These may sometimes strongly differ from the osculating orbital elements provided by other sources.[83][85] Their orbital elements are all based on a reference epoch of 1 January 2000.[83]

| Key | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Small regular moons |

♠ Titan |

† Other round moons |

♦ Inuit group |

♣ Gallic group |

‡ Norse group |

§ Outlier prograde irregular moons |

| Label [lower-alpha 6] |

Name | Pronunciation | Image | Abs. magn.[lower-alpha 7] |

Diameter (km)[lower-alpha 8] |

Mass (×1015 kg)[lower-alpha 9] |

Semi-major axis (km)[lower-alpha 10] |

Orbital period (d)[lower-alpha 10][lower-alpha 11] | Inclination (°)[lower-alpha 10][lower-alpha 12] |

Eccentricity[lower-alpha 10] | Position | Discovery year[94] |

Year announced | Discoverer[41][94] | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Q | S/2009 S 1 | — | 99 — | 0.3 | 0.0000071 ≈ 0.0000071

|| 116900 116900 |

0.47150 0.47150 | 0 ≈ 0.0 | 0 ≈ 0.000 | outer B Ring | 2009 | 2009 | Cassini[28] | |||

| A | (moonlets) | — | 99 — | 0.22 0.04–0.4 | 0.000017 < 0.000017

|| 130000 ≈ 130000 |

0.55 ≈ 0.55 | 0 ≈ 0.0 | 0 ≈ 0.000 | Three 1,000 km bands within A Ring[4] | 2006 | — | Cassini | |||

| 18 XVIII | Pan | /ˈpæn/ | 9.2 | 27.4 27.4 (34.6 × 28.2 × 21.0) |

4.30 | 133600 | 0.57505 +0.57505 | 0.0 | 0.000 | in Encke Division | 1990 | 1990 | Showalter | ||

| 35 XXXV | Daphnis | /ˈdæfnəs/ | — | 7.8 7.8 (9.8 × 8.4 × 5.6) |

0.068 | 136500 | 0.59408 +0.59408 | 0.0 | 0.000 | in Keeler Gap | 2005 | 2005 | Cassini | ||

| 15 XV | Atlas | /ˈætləs/ | 8.5 | 29.8 29.8 (40.8 × 35.4 × 18.6) |

5.490 | 137700 | 0.60460 +0.60460 | 0.0 | 0.001 | 1980 | 1980 | Voyager 1 | |||

| 16 XVI | Prometheus | /proʊˈmiːθiəs/ |  |

6.7 | 85.6 85.6 (137 × 81 × 56) |

159.72 | 139400 | 0.61588 +0.61588 | 0.0 | 0.002 | F Ring shepherd | 1980 | 1980 | Voyager 1 | |

| 17 XVII | Pandora | /pænˈdɔːrə/ | 6.5 | 80.0 80.0 (103 × 79 × 63) |

135.7 | 141700 | 0.63137 +0.63137 | 0.0 | 0.004 | 1980 | 1980 | Voyager 1 | |||

| 11 XI | Epimetheus | /ɛpəˈmiːθiəs/ | 5.5 | 117.2 117.2 (130 × 116 × 107) |

525.607 | 151400 | 0.69701 +0.69701 | 0.3 | 0.020 | co-orbital with Janus | 1966 | 1967 | Fountain & Larson | ||

| 10 X | Janus | /ˈdʒeɪnəs/ | 4.5 | 178.0 178.0 (203 × 186 × 149) |

1893.88 | 151500 | 0.69735 +0.69735 | 0.2 | 0.007 | co-orbital with Epimetheus | 1966 | 1967 | Dollfus | ||

| 53 LIII | Aegaeon | /iːˈdʒiːɒn/ | — | 0.66 0.66 (1.4 × 0.5 × 0.4) |

0.0000782 | 167500 | 0.80812 +0.80812 | 0.0 | 0.000 | G Ring moonlet | 2008 | 2009 | Cassini | ||

| 01 I | †Mimas | /ˈmaɪməs/ |  |

3.2 | 396.4 396.4 (416 × 393 × 381) |

37509.4 | 186000 | 0.94242 +0.94242 | 1.6 | 0.020 | 1789 | 1789 | Herschel | ||

| 32 XXXII | Methone | /məˈθoʊniː/ | — | 2.90 2.90 (3.88 × 2.58 × 2.42) |

0.00392 | 194700 | 1.00955 +1.00955 | 0.0 | 0.002 | Alkyonides | 2004 | 2004 | Cassini | ||

| 49 XLIX | Anthe | /ˈænθiː/ |  |

— | 1.8 | 0.0015 ≈ 0.0015 | 198100 | 1.03890 +1.03890 | 0.0 | 0.002 | Alkyonides | 2007 | 2007 | Cassini | |

| 33 XXXIII | Pallene | /pəˈliːniː/ |  |

— | 4.46 4.46 (5.76 × 4.16 × 3.68) |

0.023 ≈ 0.023 | 212300 | 1.15606 +1.15606 | 0.2 | 0.004 | Alkyonides | 2004 | 2004 | Cassini | |

| 02 II | †Enceladus | /ɛnˈsɛlədəs/ |  |

2.1 | 504.2 504.2 (513 × 503 × 497) |

108031.8 | 238400 | 1.37022 +1.37022 | 0.0 | 0.005 | Generates the E ring | 1789 | 1789 | Herschel | |

| 03 III | †Tethys | /ˈtiːθəs/ |  |

0.7 | 1062.2 1062.2 (1077 × 1057 × 1053) |

617495.9 | 295000 | 1.887802 +1.88780 | 1.1 | 0.001 | 1684 | 1684 | Cassini | ||

| 13 XIII | Telesto | /təˈlɛstoʊ/ | 8.7 | 24.6 24.6 (33.2 × 23.4 × 19.2) |

3.9 ≈ 3.9 | 295000 | 1.887802 +1.88780 | 1.2 | 0.001 | leading Tethys trojan (L4) | 1980 | 1980 | Smith et al. | ||

| 14 XIV | Calypso | /kəˈlɪpsoʊ/ | 9.2 | 19.0 19.0 (29.4 × 18.6 × 12.8) |

1.8 ≈ 1.8 | 295000 | 1.887803 +1.88780 | 1.5 | 0.001 | trailing Tethys trojan (L5) | 1980 | 1980 | Pascu et al. | ||

| 12 XII | Helene | /ˈhɛləniː/ |  |

8.2 | 36.2 36.2 (45.2 × 39.2 × 26.6) |

7.1 | 377600 | 2.73692 +2.73692 | 0.2 | 0.007 | leading Dione trojan (L4) | 1980 | 1980 | Laques & Lecacheux | |

| 34 XXXIV | Polydeuces | /pɒliˈdjuːsiːz/ | — | 3.06 3.06 (3.50 × 3.10 × 2.62) |

0.0075 ≈ 0.0075 | 377600 | 2.73692 +2.73692 | 0.2 | 0.019 | trailing Dione trojan (L5) | 2004 | 2004 | Cassini | ||

| 04 IV | †Dione | /daɪˈoʊniː/ | .jpg) |

0.8 | 1122.8 1122.8 (1128 × 1123 × 1119) |

1095486.8 | 377700 | 2.73692 +2.73692 | 0.0 | 0.002 | 1684 | 1684 | Cassini | ||

| 05 V | †Rhea | /ˈreɪə/ |  |

0.1 | 1527.6 1527.6 (1530 × 1526 × 1525) |

2306485.4 | 527200 | 4.51750 +4.51750 | 0.3 | 0.001 | 1672 | 1673 | Cassini | ||

| 06 VI | ♠Titan | /ˈtaɪtən/ |  |

–1.3 | 5149.46 5149.46 (5149 × 5149 × 5150) |

134518035.4 | 1221900 | 15.9454 +15.9454 | 0.3 | 0.029 | 1655 | 1656 | Huygens | ||

| 07 VII | Hyperion | /haɪˈpɪəriən/ |  |

4.8 | 270.0 270.0 (360 × 266 × 205) |

5551.0 | 1481500 | 21.2767 +21.2767 | 0.6 | 0.105 | in 4:3 resonance with Titan | 1848 | 1848 | Bond & Lassell | |

| 08 VIII | †Iapetus | /aɪˈæpətəs/ |  |

1.2 | 1468.6 1468.6 (1491 × 1491 × 1424) |

1805659.1 | 3561700 | 79.3310 +79.3310 | 7.6 | 0.028 | 1671 | 1673 | Cassini | ||

| R | ♦S/2019 S 1 | — | 15.3 | 6 ≈ 6 | 0.11 ≈ 0.11 | 11245400 | 445.51 +445.51 | 49.5 | 0.384 | Inuit group (Kiviuq) | 2019 | 2021 | Ashton et al. | ||

| 24 XXIV | ♦Kiviuq | /ˈkɪviək/ | 12.7 | 19 ≈ 19 | 3.6 ≈ 3.6 | 11307300 | 449.13 +449.13 | 48.9 | 0.182 | Inuit group (Kiviuq) | 2000 | 2000 | Gladman et al. | ||

| Zza | ♦S/2005 S 4 | — | 15.7 | 5 ≈ 5 | 0.065 ≈ 0.065 | 11324500 | 450.22 +450.22 | 48.0 | 0.315 | Inuit group (Kiviuq) | 2005 | 2023 | Sheppard et al. | ||

| S | ♦S/2020 S 1 | — | 15.9 | 4 ≈ 4 | 0.034 ≈ 0.034 | 11338700 | 451.10 +451.10 | 48.2 | 0.337 | Inuit group (Kiviuq) | 2020 | 2023 | Ashton et al. | ||

| 22 XXII | ♦Ijiraq | /ˈiːɪrɒk/ | 13.3 | 15 ≈ 15 | 1.8 ≈ 1.8 | 11344600 | 451.46 +451.46 | 49.2 | 0.353 | Inuit group (Kiviuq) | 2000 | 2000 | Gladman et al. | ||

| 09 IX | ‡Phoebe | /ˈfiːbi/ |  |

6.7 | 213.0 213.0 (219 × 217 × 204) |

8312.3 | 12929400 | 550.30 −550.30 | 175.2 | 0.164 | Norse group (Phoebe) | 1898 | 1899 | Pickering | |

| Zzzc | ‡S/2006 S 20 | — | 15.7 | 5 ≈ 5 | 0.065 ≈ 0.065 | 13193800 | 567.27 −567.27 | 173.1 | 0.206 | Norse group (Phoebe) | 2006 | 2023 | Sheppard et al. | ||

| T | ‡S/2006 S 9 | — | 16.5 | 3 ≈ 3 | 0.014 ≈ 0.014 | 14406600 | 647.89 −647.89 | 173.0 | 0.248 | Norse group (Phoebe) | 2006 | 2023 | Sheppard et al. | ||

| 20 XX | ♦Paaliaq | /ˈpɑːliɒk/ | 11.7 | 30 ≈ 30 | 14 ≈ 14 | 14997300 | 687.08 +687.08 | 47.1 | 0.384 | Inuit group (Paaliaq) | 2000 | 2000 | Gladman et al. | ||

| 27 XXVII | ‡Skathi | /ˈskɑːði/ | 14.4 | 9 ≈ 9 | 0.38 ≈ 0.38 | 15575100 | 728.10 −728.10 | 149.7 | 0.265 | Norse group | 2000 | 2000 | Gladman et al. | ||

| U | ‡S/2007 S 5 | — | 16.2 | 4 ≈ 4 | 0.034 ≈ 0.034 | 15835700 | 746.88 −746.88 | 158.4 | 0.104 | Norse group | 2007 | 2023 | Sheppard et al. | ||

| Zzb | ‡S/2007 S 7 | — | 16.2 | 4 ≈ 4 | 0.034 ≈ 0.034 | 15931700 | 754.29 −754.29 | 169.2 | 0.217 | Norse group | 2007 | 2023 | Sheppard et al. | ||

| O | ‡S/2007 S 2 | — | 15.6 | 5 ≈ 5 | 0.065 ≈ 0.065 | 15939100 | 754.90 −754.90 | 174.1 | 0.232 | Norse group | 2007 | 2007 | Sheppard et al. | ||

| K | ‡S/2004 S 37 | — | 15.9 | 4 ≈ 4 | 0.034 ≈ 0.034 | 15940400 | 754.48 −754.48 | 158.2 | 0.447 | Norse group | 2004 | 2019 | Sheppard et al. | ||

| Zu | ‡S/2004 S 47 | — | 16.3 | 4 ≈ 4 | 0.034 ≈ 0.034 | 16050600 | 762.49 −762.49 | 160.9 | 0.291 | Norse group | 2004 | 2023 | Sheppard et al. | ||

| V | ‡S/2004 S 40 | — | 16.3 | 4 ≈ 4 | 0.034 ≈ 0.034 | 16075600 | 764.60 −764.60 | 169.2 | 0.297 | Norse group | 2004 | 2023 | Sheppard et al. | ||

| 26 XXVI | ♣Albiorix | /ˌælbiˈɒrɪks/ |  |

11.2 | 28.6 | 12 ≈ 12 | 16329100 | 783.49 +783.49 | 38.9 | 0.470 | Gallic group | 2000 | 2000 | Holman | |

| W | ‡S/2019 S 2 | — | 16.5 | 3 ≈ 3 | 0.014 ≈ 0.014 | 16559900 | 799.82 −799.82 | 173.3 | 0.279 | Norse group | 2019 | 2023 | Ashton et al. | ||

| 37 XXXVII | ♣Bebhionn | /ˈbeɪvɪn/ | 15.0 | 7 ≈ 7 | 0.18 ≈ 0.18 | 17028900 | 834.94 +834.94 | 37.4 | 0.482 | Gallic group | 2004 | 2005 | Sheppard et al. | ||

| Zzc | ♣S/2007 S 8 | — | 16.0 | 4 ≈ 4 | 0.034 ≈ 0.034 | 17049000 | 836.90 +836.90 | 36.2 | 0.490 | Gallic group | 2007 | 2023 | Sheppard et al. | ||

| 60 LX | ♣S/2004 S 29 | — | 15.8 | 5 ≈ 5 | 0.065 ≈ 0.065 | 17063900 | 837.78 +837.78 | 38.6 | 0.485 | Gallic group | 2004 | 2019 | Sheppard et al. | ||

| X | ‡S/2019 S 3 | — | 16.2 | 4 ≈ 4 | 0.034 ≈ 0.034 | 17077200 | 837.74 −837.74 | 166.9 | 0.249 | Norse group | 2019 | 2023 | Ashton et al. | ||

| Zzd | ‡S/2020 S 7 | — | 16.8 | 3 ≈ 3 | 0.014 ≈ 0.014 | 17400000 | 861.70 −861.70 | 161.5 | 0.500 | Norse group | 2020 | 2023 | Ashton et al. | ||

| I | ♦S/2004 S 31 | — | 15.6 | 5 ≈ 5 | 0.065 ≈ 0.065 | 17497300 | 866.10 +866.10 | 48.1 | 0.159 | Inuit group (Siarnaq) | 2004 | 2019 | Sheppard et al. | ||

| 28 XXVIII | ♣Erriapus | /ɛriˈæpəs/ | 13.7 | 12 ≈ 12 | 0.95 ≈ 0.95 | 17507200 | 871.10 +871.10 | 38.7 | 0.462 | Gallic group | 2000 | 2000 | Gladman et al. | ||

| 47 XLVII | ‡Skoll | /ˈskɒl/ | 15.4 | 6 ≈ 6 | 0.11 ≈ 0.11 | 17625700 | 878.44 −878.44 | 158.4 | 0.470 | Norse group | 2006 | 2006 | Sheppard et al. | ||

| 52 LII | ♦Tarqeq | /ˈtɑːrkeɪk/ | 14.8 | 7 ≈ 7 | 0.18 ≈ 0.18 | 17748200 | 884.98 +884.98 | 49.7 | 0.119 | Inuit group (Siarnaq) | 2007 | 2007 | Sheppard et al. | ||

| Zze | ♦S/2019 S 14 | — | 16.3 | 4 ≈ 4 | 0.034 ≈ 0.034 | 17853000 | 893.14 +893.14 | 46.2 | 0.172 | Inuit group (Siarnaq) | 2019 | 2023 | Ashton et al. | ||

| Y | ‡S/2020 S 2 | — | 16.9 | 3 ≈ 3 | 0.014 ≈ 0.014 | 17869300 | 897.60 −897.60 | 170.7 | 0.152 | Norse group | 2020 | 2023 | Ashton et al. | ||

| 29 XXIX | ♦Siarnaq | /ˈsiːɑːrnək/ | 10.6 | 39.3 | 32 ≈ 32 | 17880800 | 895.87 +895.87 | 48.2 | 0.311 | Inuit group (Siarnaq) | 2000 | 2000 | Gladman et al. | ||

| Za | ‡S/2019 S 4 | — | 16.5 | 3 ≈ 3 | 0.014 ≈ 0.014 | 17956700 | 904.26 −904.26 | 170.1 | 0.409 | Norse group | 2019 | 2023 | Ashton et al. | ||

| Z | ♦S/2020 S 3 | — | 16.4 | 3 ≈ 3 | 0.014 ≈ 0.014 | 18054700 | 907.99 +907.99 | 46.1 | 0.144 | Inuit group (Siarnaq) | 2020 | 2023 | Ashton et al. | ||

| Zb | ‡S/2004 S 41 | — | 16.3 | 4 ≈ 4 | 0.034 ≈ 0.034 | 18095000 | 914.61 −914.61 | 165.7 | 0.300 | Norse group | 2004 | 2023 | Sheppard et al. | ||

| 21 XXI | ♣Tarvos | /ˈtɑːrvəs/ | 13.1 | 16 ≈ 16 | 2.1 ≈ 2.1 | 18215100 | 926.37 +926.37 | 38.6 | 0.528 | Gallic group | 2000 | 2000 | Gladman et al. | ||

| Zc | ♣S/2020 S 4 | — | 17.0 | 3 ≈ 3 | 0.014 ≈ 0.014 | 18235500 | 926.92 +926.92 | 40.1 | 0.495 | Gallic group | 2020 | 2023 | Ashton et al. | ||

| Zf | ‡S/2004 S 42 | — | 16.1 | 4 ≈ 4 | 0.034 ≈ 0.034 | 18240800 | 925.91 −925.91 | 165.7 | 0.158 | Norse group | 2004 | 2023 | Sheppard et al. | ||

| 44 XLIV | ‡Hyrrokkin | /hɪˈrɒkən/ | 14.3 | 9 ≈ 9 | 0.38 ≈ 0.38 | 18342600 | 931.89 −931.89 | 150.3 | 0.331 | Norse group | 2004 | 2005 | Sheppard et al. | ||

| 51 LI | ‡Greip | /ˈɡreɪp/ | 15.3 | 6 ≈ 6 | 0.11 ≈ 0.11 | 18380400 | 936.98 −936.98 | 173.4 | 0.317 | Norse group | 2006 | 2006 | Sheppard et al. | ||

| Zc | ♦S/2020 S 5 | — | 16.6 | 3 ≈ 3 | 0.014 ≈ 0.014 | 18391300 | 933.88 +933.88 | 48.2 | 0.220 | Inuit group (Siarnaq) | 2020 | 2023 | Ashton et al. | ||

| D | ‡S/2004 S 13 | — | 16.3 | 4 ≈ 4 | 0.034 ≈ 0.034 | 18453300 | 942.57 −942.57 | 169.0 | 0.265 | Norse group | 2004 | 2005 | Sheppard et al. | ||

| Ze | ‡S/2007 S 6 | — | 16.4 | 3 ≈ 3 | 0.014 ≈ 0.014 | 18544900 | 949.50 −949.50 | 166.5 | 0.169 | Norse group | 2007 | 2023 | Sheppard et al. | ||

| 25 XXV | ‡Mundilfari | /mʊndəlˈværi/ | 14.6 | 8 ≈ 8 | 0.27 ≈ 0.27 | 18590300 | 952.95 −952.95 | 168.4 | 0.210 | Norse group | 2000 | 2000 | Gladman et al. | ||

| M | ‡S/2006 S 1 | — | 15.6 | 5 ≈ 5 | 0.065 ≈ 0.065 | 18745000 | 964.14 −964.14 | 156.0 | 0.105 | Norse group | 2006 | 2006 | Sheppard et al. | ||

| Zi | ‡S/2004 S 43 | — | 16.3 | 4 ≈ 4 | 0.034 ≈ 0.034 | 18935000 | 980.08 −980.08 | 171.1 | 0.432 | Norse group | 2004 | 2023 | Sheppard et al. | ||

| Zg | ‡S/2006 S 10 | — | 16.4 | 3 ≈ 3 | 0.014 ≈ 0.014 | 18979900 | 983.14 −983.14 | 161.6 | 0.151 | Norse group | 2006 | 2023 | Sheppard et al. | ||

| Zh | ‡S/2019 S 5 | — | 16.6 | 3 ≈ 3 | 0.014 ≈ 0.014 | 19076900 | 990.38 −990.38 | 158.8 | 0.215 | Norse group | 2019 | 2023 | Ashton et al. | ||

| 54 LIV | ‡Gridr | /ˈɡriːðər/ | 15.8 | 5 ≈ 5 | 0.065 ≈ 0.065 | 19250700 | 1004.75 −1004.75 | 163.9 | 0.187 | Norse group | 2004 | 2019 | Sheppard et al. | ||

| 38 XXXVIII | ‡Bergelmir | /bɛərˈjɛlmɪər/ | 15.2 | 6 ≈ 6 | 0.11 ≈ 0.11 | 19269100 | 1005.58 −1005.58 | 158.7 | 0.144 | Norse group | 2004 | 2005 | Sheppard et al. | ||

| 50 L | ‡Jarnsaxa | /jɑːrnˈsæksə/ | 15.6 | 5 ≈ 5 | 0.065 ≈ 0.065 | 19279700 | 1006.92 −1006.92 | 163.0 | 0.219 | Norse group | 2006 | 2006 | Sheppard et al. | ||

| 31 XXXI | ‡Narvi | /ˈnɑːrvi/ | 14.5 | 8 ≈ 8 | 0.27 ≈ 0.27 | 19286500 | 1003.84 −1003.84 | 143.7 | 0.449 | Norse group | 2003 | 2003 | Sheppard et al. | ||

| 23 XXIII | ‡Suttungr | /ˈsʊtʊŋɡər/ | 14.6 | 8 ≈ 8 | 0.27 ≈ 0.27 | 19391700 | 1016.71 −1016.71 | 175.0 | 0.116 | Norse group | 2000 | 2000 | Gladman et al. | ||

| P | ‡S/2007 S 3 | — | 15.7 | 5 ≈ 5 | 0.065 ≈ 0.065 | 19513700 | 1026.35 −1026.35 | 175.6 | 0.162 | Norse group | 2007 | 2007 | Sheppard et al. | ||

| Zj | ‡S/2004 S 44 | — | 15.8 | 5 ≈ 5 | 0.065 ≈ 0.065 | 19515400 | 1026.16 −1026.16 | 167.7 | 0.129 | Norse group | 2004 | 2023 | Sheppard et al. | ||

| Zm | §S/2006 S 12 | — | 16.2 | 4 ≈ 4 | 0.034 ≈ 0.034 | 19569800 | 1035.05 +1035.05 | 38.6 | 0.542 | Gallic group?[lower-alpha 13] | 2006 | 2023 | Sheppard et al. | ||

| Zk | ‡S/2004 S 45 | — | 16.0 | 4 ≈ 4 | 0.034 ≈ 0.034 | 19693600 | 1038.70 −1038.70 | 154.0 | 0.551 | Norse group | 2004 | 2023 | Sheppard et al. | ||

| 43 XLIII | ‡Hati | /ˈhɑːti/ | 15.4 | 6 ≈ 6 | 0.11 ≈ 0.11 | 19697100 | 1040.29 −1040.29 | 164.1 | 0.375 | Norse group | 2004 | 2005 | Sheppard et al. | ||

| E | ‡S/2004 S 17 | — | 16.0 | 4 ≈ 4 | 0.034 ≈ 0.034 | 19699300 | 1040.86 −1040.86 | 167.9 | 0.162 | Norse group | 2004 | 2005 | Sheppard et al. | ||

| Zl | ‡S/2006 S 11 | — | 16.5 | 3 ≈ 3 | 0.014 ≈ 0.014 | 19711900 | 1042.28 −1042.28 | 174.1 | 0.144 | Norse group | 2004 | 2023 | Sheppard et al. | ||

| C | ‡S/2004 S 12 | — | 15.9 | 4 ≈ 4 | 0.034 ≈ 0.034 | 19801200 | 1048.57 −1048.57 | 164.7 | 0.337 | Norse group | 2004 | 2005 | Sheppard et al. | ||

| 59 LIX | ‡Eggther | /ˈɛɡθɛər/ | 15.4 | 6 ≈ 6 | 0.11 ≈ 0.11 | 19844700 | 1052.33 −1052.33 | 165.0 | 0.157 | Norse group | 2004 | 2019 | Sheppard et al. | ||

| Zo | ‡S/2006 S 13 | — | 16.1 | 4 ≈ 4 | 0.034 ≈ 0.034 | 19953800 | 1060.63 −1060.63 | 162.0 | 0.313 | Norse group | 2006 | 2023 | Sheppard et al. | ||

| Zn | §S/2019 S 6 | — | 16.1 | 4 ≈ 4 | 0.034 ≈ 0.034 | 20048600 | 1066.40 +1066.40 | 41.3 | 0.259 | Inuit/Gallic group[lower-alpha 5] | 2019 | 2023 | Ashton et al. | ||

| Zzy | ‡S/2007 S 9 | — | 16.1 | 4 ≈ 4 | 0.034 ≈ 0.034 | 20174600 | 1078.07 −1078.07 | 159.3 | 0.360 | Norse group | 2007 | 2023 | Sheppard et al. | ||

| Zp | ‡S/2019 S 7 | — | 16.3 | 4 ≈ 4 | 0.034 ≈ 0.034 | 20181300 | 1080.29 −1080.29 | 174.2 | 0.232 | Norse group | 2019 | 2023 | Ashton et al. | ||

| Zq | ‡S/2019 S 8 | — | 16.3 | 4 ≈ 4 | 0.034 ≈ 0.034 | 20284400 | 1088.68 −1088.68 | 172.8 | 0.311 | Norse group | 2019 | 2023 | Ashton et al. | ||

| 40 XL | ‡Farbauti | /fɑːrˈbaʊti/ | 15.8 | 5 ≈ 5 | 0.065 ≈ 0.065 | 20292500 | 1087.29 −1087.29 | 157.7 | 0.248 | Norse group | 2004 | 2005 | Sheppard et al. | ||

| 30 XXX | ‡Thrymr | /ˈθrɪmər/ | 14.3 | 9 ≈ 9 | 0.38 ≈ 0.38 | 20326500 | 1091.84 −1091.84 | 174.8 | 0.467 | Norse group | 2000 | 2000 | Gladman et al. | ||

| 39 XXXIX | ‡Bestla | /ˈbɛstlə/ | 14.6 | 8 ≈ 8 | 0.27 ≈ 0.27 | 20337900 | 1087.46 −1087.46 | 136.3 | 0.461 | Norse group | 2004 | 2005 | Sheppard et al. | ||

| Zr | ‡S/2019 S 9 | — | 16.3 | 4 ≈ 4 | 0.034 ≈ 0.034 | 20359000 | 1093.11 −1093.11 | 159.5 | 0.433 | Norse group | 2019 | 2023 | Ashton et al. | ||

| Zs | ‡S/2004 S 46 | — | 16.4 | 3 ≈ 3 | 0.014 ≈ 0.014 | 20513000 | 1107.58 −1107.58 | 177.2 | 0.249 | Norse group | 2004 | 2023 | Sheppard et al. | ||

| 55 LV | ‡Angrboda | /ˈɑːŋɡərboʊðə/ | 16.2 | 4 ≈ 4 | 0.034 ≈ 0.034 | 20591000 | 1114.05 −1114.05 | 177.4 | 0.216 | Norse group | 2004 | 2019 | Sheppard et al. | ||

| Zv | ‡S/2019 S 11 | — | 16.2 | 4 ≈ 4 | 0.034 ≈ 0.034 | 20663700 | 1115.00 −1115.00 | 144.6 | 0.513 | Norse group | 2019 | 2023 | Ashton et al. | ||

| 36 XXXVI | ‡Aegir | /ˈaɪ.ɪər/ | 15.5 | 5 ≈ 5 | 0.065 ≈ 0.065 | 20664600 | 1119.33 −1119.33 | 166.9 | 0.255 | Norse group | 2004 | 2005 | Sheppard et al. | ||

| 61 LXI | ‡Beli | /ˈbiːli/ | 16.1 | 4 ≈ 4 | 0.034 ≈ 0.034 | 20703800 | 1121.76 −1121.76 | 158.9 | 0.087 | Norse group | 2004 | 2019 | Sheppard et al. | ||

| Zt | ‡S/2019 S 10 | — | 16.7 | 3 ≈ 3 | 0.014 ≈ 0.014 | 20713400 | 1123.04 −1123.04 | 163.9 | 0.249 | Norse group | 2019 | 2023 | Ashton et al. | ||

| Zx | ‡S/2019 S 12 | — | 16.3 | 4 ≈ 4 | 0.034 ≈ 0.034 | 20904500 | 1138.85 −1138.85 | 167.1 | 0.476 | Norse group | 2019 | 2023 | Ashton et al. | ||

| 57 LVII | ‡Gerd | /ˈjɛərð/ | 15.9 | 4 ≈ 4 | 0.034 ≈ 0.034 | 20947500 | 1142.97 −1142.97 | 174.4 | 0.517 | Norse group | 2004 | 2019 | Sheppard et al. | ||

| Zz | ‡S/2019 S 13 | — | 16.7 | 3 ≈ 3 | 0.014 ≈ 0.014 | 20965800 | 1144.92 −1144.92 | 177.3 | 0.318 | Norse group | 2019 | 2023 | Ashton et al. | ||

| Zw | ‡S/2006 S 14 | — | 16.5 | 3 ≈ 3 | 0.014 ≈ 0.014 | 21062100 | 1152.68 −1152.68 | 166.7 | 0.060 | Norse group | 2006 | 2023 | Sheppard et al. | ||

| 62 LXII | ‡Gunnlod | /ˈɡʊnlɒð/ | 15.6 | 5 ≈ 5 | 0.065 ≈ 0.065 | 21141900 | 1157.98 −1157.98 | 160.4 | 0.251 | Norse group | 2004 | 2019 | Sheppard et al. | ||

| Zzf | ‡S/2019 S 15 | — | 16.6 | 3 ≈ 3 | 0.014 ≈ 0.014 | 21189700 | 1161.54 −1161.54 | 157.7 | 0.257 | Norse group | 2019 | 2023 | Ashton et al. | ||

| Zy | ‡S/2020 S 6 | — | 16.6 | 3 ≈ 3 | 0.014 ≈ 0.014 | 21265300 | 1168.86 −1168.86 | 166.9 | 0.481 | Norse group | 2020 | 2023 | Ashton et al. | ||

| B | ‡S/2004 S 7 | — | 15.6 | 5 ≈ 5 | 0.065 ≈ 0.065 | 21328200 | 1173.93 −1173.93 | 164.9 | 0.511 | Norse group | 2004 | 2005 | Sheppard et al. | ||

| N | ‡S/2006 S 3 | — | 15.6 | 5 ≈ 5 | 0.065 ≈ 0.065 | 21353000 | 1174.76 −1174.76 | 156.1 | 0.432 | Norse group | 2006 | 2006 | Sheppard et al. | ||

| Zzg | ‡S/2005 S 5 | — | 16.4 | 3 ≈ 3 | 0.014 ≈ 0.014 | 21366200 | 1177.82 −1177.82 | 169.5 | 0.588 | Norse group | 2005 | 2023 | Sheppard et al. | ||

| 56 LVI | ‡Skrymir | /ˈskrɪmɪər/ | 15.6 | 5 ≈ 5 | 0.065 ≈ 0.065 | 21448000 | 1185.15 −1185.15 | 175.6 | 0.437 | Norse group | 2004 | 2019 | Sheppard et al. | ||

| Zzi | ‡S/2006 S 16 | — | 16.5 | 3 ≈ 3 | 0.014 ≈ 0.014 | 21720700 | 1207.52 −1207.52 | 164.1 | 0.204 | Norse group | 2006 | 2023 | Sheppard et al. | ||

| Zzh | ‡S/2006 S 15 | — | 16.2 | 4 ≈ 4 | 0.034 ≈ 0.034 | 21799400 | 1213.96 −1213.96 | 161.1 | 0.117 | Norse group | 2006 | 2023 | Sheppard et al. | ||

| H | ‡S/2004 S 28 | — | 15.8 | 5 ≈ 5 | 0.065 ≈ 0.065 | 21865900 | 1220.68 −1220.68 | 167.9 | 0.159 | Norse group | 2004 | 2019 | Sheppard et al. | ||

| Zzl | ‡S/2020 S 8 | — | 16.4 | 3 ≈ 3 | 0.014 ≈ 0.014 | 21966700 | 1228.12 −1228.12 | 161.8 | 0.252 | Norse group | 2020 | 2023 | Ashton et al. | ||

| 65 LXV | ‡Alvaldi | /ɔːlˈvɔːldi/ | 15.6 | 5 ≈ 5 | 0.065 ≈ 0.065 | 21995600 | 1232.19 −1232.19 | 177.4 | 0.238 | Norse group | 2004 | 2019 | Sheppard et al. | ||

| 45 XLV | ‡Kari | /ˈkɑːri/ | 14.5 | 8 ≈ 8 | 0.27 ≈ 0.27 | 22029700 | 1231.01 −1231.01 | 153.0 | 0.482 | Norse group | 2006 | 2006 | Sheppard et al. | ||

| Zzk | ‡S/2004 S 48 | — | 16.0 | 4 ≈ 4 | 0.034 ≈ 0.034 | 22136700 | 1242.40 −1242.40 | 161.9 | 0.374 | Norse group | 2004 | 2023 | Sheppard et al. | ||

| 66 LXVI | ‡Geirrod | /ˈjeɪrɒd/ | 15.9 | 4 ≈ 4 | 0.034 ≈ 0.034 | 22259500 | 1251.14 −1251.14 | 154.4 | 0.539 | Norse group | 2004 | 2019 | Sheppard et al. | ||

| 41 XLI | ‡Fenrir | /ˈfɛnrɪər/ | 15.9 | 4 ≈ 4 | 0.034 ≈ 0.034 | 22331800 | 1260.25 −1260.25 | 164.3 | 0.136 | Norse group | 2004 | 2005 | Sheppard et al. | ||

| Zzn | ‡S/2004 S 50 | — | 16.4 | 3 ≈ 3 | 0.014 ≈ 0.014 | 22346000 | 1260.44 −1260.44 | 164.0 | 0.450 | Norse group | 2004 | 2023 | Sheppard et al. | ||

| Zzj | ‡S/2006 S 17 | — | 16.0 | 4 ≈ 4 | 0.034 ≈ 0.034 | 22384900 | 1264.58 −1264.58 | 168.7 | 0.425 | Norse group | 2006 | 2023 | Sheppard et al. | ||

| Zzm | ‡S/2004 S 49 | — | 16.0 | 4 ≈ 4 | 0.034 ≈ 0.034 | 22399700 | 1264.25 −1264.25 | 159.7 | 0.453 | Norse group | 2004 | 2023 | Sheppard et al. | ||

| Zzq | ‡S/2019 S 17 | — | 15.9 | 4 ≈ 4 | 0.034 ≈ 0.034 | 22724100 | 1291.39 −1291.39 | 155.5 | 0.546 | Norse group | 2019 | 2023 | Ashton et al. | ||

| 48 XLVIII | ‡Surtur | /ˈsɜːrtər/ | 15.8 | 5 ≈ 5 | 0.065 ≈ 0.065 | 22753800 | 1296.49 −1296.49 | 168.3 | 0.449 | Norse group | 2006 | 2006 | Sheppard et al. | ||

| Zzo | ‡S/2006 S 18 | — | 16.1 | 4 ≈ 4 | 0.034 ≈ 0.034 | 22760700 | 1298.40 −1298.40 | 169.5 | 0.131 | Norse group | 2006 | 2023 | Sheppard et al. | ||

| 46 XLVI | ‡Loge | /ˈlɔɪ.eɪ/ | 15.4 | 6 ≈ 6 | 0.11 ≈ 0.11 | 22918300 | 1311.83 −1311.83 | 166.9 | 0.192 | Norse group | 2006 | 2006 | Sheppard et al. | ||

| 19 XIX | ‡Ymir | /ˈiːmɪər/ | 12.4 | 22 ≈ 22 | 5.6 ≈ 5.6 | 22957100 | 1315.16 −1315.16 | 173.1 | 0.337 | Norse group | 2000 | 2000 | Gladman et al. | ||

| Zzs | ‡S/2019 S 19 | — | 16.5 | 3 ≈ 3 | 0.014 ≈ 0.014 | 23047200 | 1318.05 −1318.05 | 151.8 | 0.458 | Norse group | 2019 | 2023 | Ashton et al. | ||

| F | ‡S/2004 S 21 | — | 16.2 | 4 ≈ 4 | 0.034 ≈ 0.034 | 23123500 | 1325.43 −1325.43 | 153.2 | 0.394 | Norse group | 2004 | 2019 | Sheppard et al. | ||

| Zzr | ‡S/2019 S 18 | — | 16.6 | 3 ≈ 3 | 0.014 ≈ 0.014 | 23140700 | 1327.06 −1327.06 | 154.6 | 0.509 | Norse group | 2019 | 2023 | Ashton et al. | ||

| L | ‡S/2004 S 39 | — | 16.1 | 4 ≈ 4 | 0.034 ≈ 0.034 | 23195400 | 1336.17 −1336.17 | 165.9 | 0.101 | Norse group | 2004 | 2019 | Sheppard et al. | ||

| Zzp | ‡S/2019 S 16 | — | 16.7 | 3 ≈ 3 | 0.014 ≈ 0.014 | 23266700 | 1341.17 −1341.17 | 162.0 | 0.250 | Norse group | 2019 | 2023 | Ashton et al. | ||

| Zzz | ‡S/2004 S 53 | — | 16.2 | 4 ≈ 4 | 0.034 ≈ 0.034 | 23279800 | 1342.44 −1342.44 | 162.6 | 0.240 | Norse group | 2004 | 2023 | Sheppard et al. | ||

| G | §S/2004 S 24 | — | 16.0 | 4 ≈ 4 | 0.034 ≈ 0.034 | 23338900 | 1341.33 +1341.33 | 37.4 | 0.071 | Gallic group?[lower-alpha 13] | 2004 | 2019 | Sheppard et al. | ||

| J | ‡S/2004 S 36 | — | 16.1 | 4 ≈ 4 | 0.034 ≈ 0.034 | 23430300 | 1352.93 −1352.93 | 153.3 | 0.625 | Norse group | 2004 | 2019 | Sheppard et al. | ||

| 63 LXIII | ‡Thiazzi | /θiˈætsi/ | 15.9 | 4 ≈ 4 | 0.034 ≈ 0.034 | 23577500 | 1366.68 −1366.68 | 158.8 | 0.511 | Norse group | 2004 | 2019 | Sheppard et al. | ||

| Zzt | ‡S/2019 S 20 | — | 16.7 | 3 ≈ 3 | 0.014 ≈ 0.014 | 23678600 | 1375.45 −1375.45 | 156.1 | 0.354 | Norse group | 2019 | 2023 | Ashton et al. | ||

| Zzu | ‡S/2006 S 19 | — | 16.1 | 4 ≈ 4 | 0.034 ≈ 0.034 | 23801100 | 1389.33 −1389.33 | 175.5 | 0.467 | Norse group | 2006 | 2023 | Sheppard et al. | ||

| 64 LXIV | ‡S/2004 S 34 | — | 16.2 | 4 ≈ 4 | 0.034 ≈ 0.034 | 24145500 | 1420.77 −1420.77 | 168.3 | 0.279 | Norse group | 2004 | 2019 | Sheppard et al. | ||

| 42 XLII | ‡Fornjot | /ˈfɔːrnjɒt/ | 15.1 | 6 ≈ 6 | 0.11 ≈ 0.11 | 24937300 | 1494.03 −1494.03 | 169.5 | 0.214 | Norse group | 2004 | 2005 | Sheppard et al. | ||

| Zzv | ‡S/2004 S 51 | — | 16.1 | 4 ≈ 4 | 0.034 ≈ 0.034 | 25208200 | 1519.43 −1519.43 | 171.2 | 0.201 | Norse group | 2004 | 2023 | Sheppard et al. | ||

| Zzza | ‡S/2020 S 10 | — | 16.9 | 3 ≈ 3 | 0.014 ≈ 0.014 | 25314800 | 1527.22 −1527.22 | 165.6 | 0.295 | Norse group | 2020 | 2023 | Ashton et al. | ||

| Zzw | ‡S/2020 S 9 | — | 16.0 | 4 ≈ 4 | 0.034 ≈ 0.034 | 25434100 | 1534.97 −1534.97 | 161.4 | 0.531 | Norse group | 2020 | 2023 | Ashton et al. | ||

| 58 LVIII | ‡S/2004 S 26 | — | 15.7 | 5 ≈ 5 | 0.065 ≈ 0.065 | 26097100 | 1603.95 −1603.95 | 172.9 | 0.148 | Norse group | 2004 | 2019 | Sheppard et al. | ||

| Zzzb | ‡S/2019 S 21 | — | 16.2 | 4 ≈ 4 | 0.034 ≈ 0.034 | 26439000 | 1636.32 −1636.32 | 171.9 | 0.155 | Norse group | 2019 | 2023 | Ashton et al. | ||

| Zzx | ‡S/2004 S 52 | — | 16.5 | 3 ≈ 3 | 0.014 ≈ 0.014 | 26448100 | 1633.98 −1633.98 | 165.3 | 0.292 | Norse group | 2004 | 2023 | Sheppard et al. |

Unconfirmed

These F Ring moonlets listed in the following table (observed by Cassini) have not been confirmed as solid bodies. It is not yet clear if these are real satellites or merely persistent clumps within the F Ring.[23]

| Name | Image | Diameter (km) | Semi-major axis (km)[52] |

Orbital period (d)[52] |

Position | Discovery year | Status |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S/2004 S 3 and S 4[lower-alpha 14] |  |

≈ 3–5 | ≈ 140300 | ≈ +0.619 | uncertain objects around the F Ring | 2004 | Were undetected in thorough imaging of the region in November 2004, making their existence improbable |

| S/2004 S 6 |  |

≈ 3–5 | ≈ 140130 | +0.61801 | 2004 | Consistently detected into 2005, may be surrounded by fine dust and have a very small physical core |

Spurious

Two moons were claimed to be discovered by different astronomers but never seen again. Both moons were said to orbit between Titan and Hyperion.[95]

- Chiron which was supposedly sighted by Hermann Goldschmidt in 1861, but never observed by anyone else.[95]

- Themis was allegedly discovered in 1905 by astronomer William Pickering, but never seen again. Nevertheless, it was included in numerous almanacs and astronomy books until the 1960s.[95]

Hypothetical

In 2022, scientists of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology proposed the hypothetical former moon Chrysalis, using data from the Cassini–Huygens mission. Chrysalis would have orbited between Titan and Iapetus, but its orbit would have gradually become more eccentric until it was torn apart by Saturn. 99% of its mass would have been absorbed by Saturn, while the remaining 1% would have formed Saturn's rings.[96][97]

Temporary

Much like Jupiter, asteroids and comets will infrequently make close approaches to Saturn, even more infrequently becoming captured into orbit of the planet. The comet P/2020 F1 (Leonard) is calculated to have made a close approach of 978000±65000 km (608000±40000 mi) to Saturn on 8 May 1936, closer than the orbit of Titan to the planet, with an orbital eccentricity of only 1.098±0.007. The comet may have been orbiting Saturn prior to this as a temporary satellite, but difficulty modelling the non-gravitational forces makes whether or not it was indeed a temporary satellite uncertain.[98]

Other comets and asteroids may have temporarily orbited Saturn at some point, but none are presently known to have.

Formation

It is thought that the Saturnian system of Titan, mid-sized moons, and rings developed from a set-up closer to the Galilean moons of Jupiter, though the details are unclear. It has been proposed either that a second Titan-sized moon broke up, producing the rings and inner mid-sized moons,[99] or that two large moons fused to form Titan, with the collision scattering icy debris that formed the mid-sized moons.[100] On 23 June 2014, NASA claimed to have strong evidence that nitrogen in the atmosphere of Titan came from materials in the Oort cloud, associated with comets, and not from the materials that formed Saturn in earlier times.[70] Studies based on Enceladus's tidal-based geologic activity and the lack of evidence of extensive past resonances in Tethys, Dione, and Rhea's orbits suggest that the moons up to and including Rhea may be only 100 million years old.[101]

See also

- List of natural satellites

Notes

- ↑ 62 moons were announced 3–16 May, 2023: S/2020 S 1, S/2006 S 9, S/2007 S 5, S/2004 S 40, S/2019 S 2, S/2019 S 3, S/2020 S 2, S/2020 S 3, S/2019 S 4, S/2004 S 41, S/2020 S 4, S/2020 S 5, S/2007 S 6, S/2004 S 42, S/2006 S 10, S/2019 S 5, S/2004 S 43, S/2004 S 44, S/2004 S 45, S/2006 S 11, S/2006 S 12, S/2019 S 6, S/2006 S 13, S/2019 S 7, S/2019 S 8, S/2019 S 9, S/2004 S 46, S/2019 S 10, S/2004 S 47, S/2019 S 11, S/2006 S 14, S/2019 S 12, S/2020 S 6, S/2019 S 13, S/2005 S 4, S/2007 S 7, S/2007 S 8, S/2020 S 7, S/2019 S 14, S/2019 S 15, S/2005 S 5, S/2006 S 15, S/2006 S 16, S/2006 S 17, S/2004 S 48, S/2020 S 8, S/2004 S 49, S/2004 S 50, S/2006 S 18, S/2019 S 16, S/2019 S 17, S/2019 S 18, S/2019 S 19, S/2019 S 20, S/2006 S 19, S/2004 S 51, S/2020 S 9, S/2004 S 52, S/2007 S 9, S/2004 S 53, S/2020 S 10, and S/2019 S 21 which were published in MPECs 2023-J21 to 2023-K05. One more moon, S/2006 S 20, was announced on 23 May 2023, which brings the final count to 146.[2][1]

- ↑ The mass of the rings is about the mass of Mimas,[11] whereas the combined mass of Janus, Hyperion and Phoebe—the most massive of the remaining moons—is about one-third of that. The total mass of the rings and small moons is around 5.5×1019 kg.

- ↑ Inktomi was once known as "The Splat".[66]

- ↑ The photometric color may be used as a proxy for the chemical composition of satellites' surfaces.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 JPL's mean orbital elements suggest an inclination that is similar to those of the Gallic group; however other sources say it belongs to the Inuit group.

- ↑ A confirmed moon is given a permanent designation by the IAU consisting of a name and a Roman numeral.[41] The eight moons that were known before 1850 are numbered in order of their distance from Saturn; the rest are numbered in the order by which they received their permanent designations. Many small moons have not yet received a permanent designation.

- ↑ Absolute magnitudes of regular satellites are calculated from their mean diameters and geometric albedos given in NASA's Saturnian Satellite Fact Sheet.[45] Absolute magnitude estimates for some small inner moons are not available as they do not have measured geometric albedos. Absolute magnitudes of irregular satellites were taken from the Minor Planet Center's Natural Satellites Ephemeris Service.[89] Calculations were made with NASA/JPL's Asteroid Size Estimator.[90]

- ↑ The diameters and dimensions of the small inner moons, from Pan to Helene, are taken from Thomas et al., 2020, Table 1.[91] Diameters and dimensions of Mimas, Enceladus, Tethys, Dione, Rhea, Iapetus, and Phoebe are from Thomas 2010, Table 1.[43] Diameters of Siarnaq and Albiorix are from Grav et al., 2015, Table 3.[84] The approximate sizes of all other irregular satellites are calculated from their absolute magnitudes with an assumed geometric albedo of 0.04,[90] which is the average value for that population.[84]

- ↑ Masses of the large round moons, including Hyperion, Phoebe, and Helene, were taken from Jacobson et al., 2022, Table 5.[92] Masses of Atlas, Prometheus, Pandora, Epimetheus, and Janus were taken from Lainey et al., 2023, Table 1.[93] Masses of Pan, Daphnis, Aegaeon, Methone, and Pallene were taken from Thomas et al., 2020, Table 2.[91] Masses of other regular satellites were calculated by multiplying their volumes with an assumed density of 500 kg/m3 (0.5 g/cm3), while masses of irregular satellites were calculated with an assumed density of 1000 kg/m3 (1.0 g/cm3).

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 10.3 Time-averaged orbital elements of all satellites were taken from JPL Solar System Dynamics.[83]

- ↑ Negative orbital periods indicate a retrograde orbit around Saturn (opposite to the planet's rotation). Orbital periods of irregular satellites may not directly correlate with their semi-major axes due to perturbations.

- ↑ Orbital inclinations of regular satellites and Phoebe are with respect to the Laplace plane. Orbital inclinations of irregular satellites are with respect to the ecliptic.[83]

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 May be part of the Gallic group because it has a similar inclination; however, it has a more distant semi-major axis.[1]

- ↑ S/2004 S 4 was most likely a transient clump—it has not been recovered since the first sighting.[23]

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 1.6 1.7 1.8 Sheppard, Scott S.; Gladman, Brett J.; Alexandersen, Mike A.; Trujillo, Chadwick A. (May 2023). "New Jupiter and Saturn Satellites Reveal New Moon Dynamical Families". Research Notes of the American Astronomical Society 7 (5): 100. doi:10.3847/2515-5172/acd766. 100. Bibcode: 2023RNAAS...7..100S.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 "MPEC 2023-K118 : S/2006 S 20". Minor Planet Electronic Circulars. Minor Planet Center. 23 May 2023. https://minorplanetcenter.net/mpec/K23/K23KB8.html. Retrieved 23 May 2023.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 Sheppard, Scott S.. "Moons of Saturn". Earth & Planets Laboratory. Carnegie Institution for Science. https://sites.google.com/carnegiescience.edu/sheppard/moons/saturnmoons. Retrieved 21 August 2022.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 4.5 4.6 4.7 Tiscareno, Matthew S.; Burns, J.A; Hedman, M.M; Porco, C.C (2008). "The population of propellers in Saturn's A Ring". Astronomical Journal 135 (3): 1083–1091. doi:10.1088/0004-6256/135/3/1083. Bibcode: 2008AJ....135.1083T.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 Ashton, Edward; Gladman, Brett; Beaudoin, Matthew (August 2021). "Evidence for a Recent Collision in Saturn's Irregular Moon Population". The Planetary Science Journal 2 (4): 12. doi:10.3847/PSJ/ac0979. Bibcode: 2021PSJ.....2..158A.

- ↑ Redd, Nola Taylor (27 March 2018). "Titan: Facts About Saturn's Largest Moon". Space.com. https://www.space.com/15257-titan-saturn-largest-moon-facts-discovery-sdcmp.html.

- ↑ "Enceladus - Overview - Planets - NASA Solar System Exploration". http://solarsystem.nasa.gov/planets/profile.cfm?Object=Enceladus.

- ↑ "Moons". http://abyss.uoregon.edu/~js/ast121/lectures/lec17.html.

- ↑ "Iapetus - NASA Science". https://science.nasa.gov/saturn/moons/iapetus/.

- ↑ https://www.nasa.gov/image-article/view-from-iapetus/#:~:text=the Saturn System.-,Iapetus (1,468 kilometers, or 912 miles across) is the,a tilt, as seen here.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Esposito, L. W. (2002). "Planetary rings". Reports on Progress in Physics 65 (12): 1741–1783. doi:10.1088/0034-4885/65/12/201. Bibcode: 2002RPPh...65.1741E.

- ↑ "Help Name 20 Newly Discovered Moons of Saturn!". Carnegie Science. 7 October 2019. https://carnegiescience.edu/NameSaturnsMoons.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 "Saturn Surpasses Jupiter After The Discovery Of 20 New Moons And You Can Help Name Them!". Carnegie Science. 7 October 2019. https://carnegiescience.edu/news/saturn-surpasses-jupiter-after-discovery-20-new-moons-and-you-can-help-name-them.

- ↑ "Huygens Discovers Luna Saturni". Astronomy Picture of the Day. March 25, 2005. http://apod.nasa.gov/apod/ap050325.html.

- ↑ Baalke, Ron. "Historical Background of Saturn's Rings (1655)". NASA/JPL. http://www2.jpl.nasa.gov/saturn/back.html#1600.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 16.2 16.3 Van Helden, Albert (1994). "Naming the satellites of Jupiter and Saturn". The Newsletter of the Historical Astronomy Division of the American Astronomical Society (32): 1–2. http://had.aas.org/hadnews/HADN32.pdf.

- ↑ Bond, W.C (1848). "Discovery of a new satellite of Saturn". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society 9: 1–2. doi:10.1093/mnras/9.1.1. Bibcode: 1848MNRAS...9....1B. https://zenodo.org/record/1431915.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 Lassell, William (1848). "Discovery of new satellite of Saturn". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society 8 (9): 195–197. doi:10.1093/mnras/8.9.195a. Bibcode: 1848MNRAS...8..195L. https://zenodo.org/record/1431913.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 Pickering, Edward C (1899). "A New Satellite of Saturn". Astrophysical Journal 9 (221): 274–276. doi:10.1086/140590. PMID 17844472. Bibcode: 1899ApJ.....9..274P.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 Fountain, John W; Larson, Stephen M (1977). "A New Satellite of Saturn?". Science 197 (4306): 915–917. doi:10.1126/science.197.4306.915. PMID 17730174. Bibcode: 1977Sci...197..915F.

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 21.2 21.3 21.4 Uralskaya, V.S (1998). "Discovery of new satellites of Saturn". Astronomical and Astrophysical Transactions 15 (1–4): 249–253. doi:10.1080/10556799808201777. Bibcode: 1998A&AT...15..249U.

- ↑ Corum, Jonathan (December 18, 2015). "Mapping Saturn's Moons". The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2015/12/18/science/space/nasa-cassini-maps-saturns-moons.html.

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 23.2 23.3 23.4 Porco, C. C. et al. (2005). "Cassini Imaging Science: Initial Results on Saturn's Rings and Small Satellites". Science 307 (5713): 1226–36. doi:10.1126/science.1108056. PMID 15731439. Bibcode: 2005Sci...307.1226P. http://ciclops.org/sci/docs/RingsSatsPaper.pdf.

- ↑ Robert Roy Britt (2004). "Hints of Unseen Moons in Saturn's Rings". http://www.space.com/scienceastronomy/saturn_update_041116.html.

- ↑ Porco, C.; The Cassini Imaging Team (July 18, 2007). "S/2007 S4". IAU Circular 8857. http://www.cbat.eps.harvard.edu/iauc/08800/08857.html.

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 26.2 26.3 Jones, G.H. et al. (2008). "The Dust Halo of Saturn's Largest Icy Moon, Rhea". Science 319 (1): 1380–84. doi:10.1126/science.1151524. PMID 18323452. Bibcode: 2008Sci...319.1380J.

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 27.2 Porco, C.; The Cassini Imaging Team (March 3, 2009). "S/2008 S1 (Aegaeon)". IAU Circular 9023. http://ciclops.org/view/5518/S2008_S_1?js=1. Retrieved March 4, 2009.

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 28.2 Porco, C.; the Cassini Imaging Team (November 2, 2009). "S/2009 S1". IAU Circular 9091. http://ciclops.org/view_popup.php?id=5926&js=1. Retrieved January 17, 2010.

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 Platt, Jane; Brown, Dwayne (14 April 2014). "NASA Cassini Images May Reveal Birth of a Saturn Moon". NASA. http://www.jpl.nasa.gov/news/news.php?release=2014-112.

- ↑ 30.0 30.1 30.2 30.3 30.4 30.5 30.6 30.7 30.8 Jewitt, David; Haghighipour, Nader (2007). "Irregular Satellites of the Planets: Products of Capture in the Early Solar System". Annual Review of Astronomy and Astrophysics 45 (1): 261–95. doi:10.1146/annurev.astro.44.051905.092459. Bibcode: 2007ARA&A..45..261J. http://www.ifa.hawaii.edu/~jewitt/papers/2007/JH07.pdf.

- ↑ 31.0 31.1 31.2 31.3 31.4 31.5 Gladman, Brett et al. (2001). "Discovery of 12 satellites of Saturn exhibiting orbital clustering". Nature 412 (6843): 1631–166. doi:10.1038/35084032. PMID 11449267. Bibcode: 2001Natur.412..163G.

- ↑ David Jewitt (May 3, 2005). "12 New Moons For Saturn". University of Hawaii. http://www2.ess.ucla.edu/~jewitt/saturn2005.html.

- ↑ Emily Lakdawalla (May 3, 2005). "Twelve New Moons For Saturn". http://planetary.org/news/2005/0503_Twelve_New_Moons_for_Saturn.html.

- ↑ Sheppard, S. S.; Jewitt, D. C.; Kleyna, J. (June 30, 2006). "Satellites of Saturn". IAU Circular 8727. http://www.dtm.ciw.edu/users/sheppard/satellites/saturn2006.html. Retrieved January 2, 2010.

- ↑ Sheppard, S. S.; Jewitt, D. C.; Kleyna, J. (May 11, 2007). "S/2007 S 1, S/2007 S 2, AND S/2007 S 3". IAU Circular 8836: 1. Bibcode: 2007IAUC.8836....1S. http://www.dtm.ciw.edu/users/sheppard/satellites/saturn2007.html. Retrieved January 2, 2010.

- ↑ Ashton, Edward; Gladman, Brett; Beaudoin, Matthew; Alexandersen, Mike; Petit, Jean-Marc (May 2022). "Discovery of the Closest Saturnian Irregular Moon, S/2019 S 1, and Implications for the Direct/Retrograde Satellite Ratio". The Astronomical Journal 3 (5): 5. doi:10.3847/PSJ/ac64a2. 107. Bibcode: 2022PSJ.....3..107A.

- ↑ 37.0 37.1 "Saturn now leads moon race with 62 newly discovered moons". UBC Science (University of British Columbia). 11 May 2023. https://science.ubc.ca/news/saturn-now-leads-moon-race-62-newly-discovered-satellites. Retrieved 11 May 2023.

- ↑ O'Callaghan, Jonathan (12 May 2023). "With 62 Newly Discovered Moons, Saturn Knocks Jupiter Off Its Pedestal - If all the objects are recognized by scientific authorities, the ringed giant world will have 145 moons in its orbit.". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 12 May 2023. https://archive.today/20230512174454/https://www.nytimes.com/2023/05/12/science/saturn-moons-jupiter.html. Retrieved 13 May 2023.

- ↑ Semeniuk, Ivan (14 May 2023). "Astronomers discover record-breaking 62 moons around Saturn". https://www.theglobeandmail.com/canada/article-astronomers-discover-record-breaking-62-moons-around-saturn/.

- ↑ 40.0 40.1 Van Helden, Albert (August 1994). "Naming the Satellites of Jupiter and Saturn". The Newsletter of the Historical Astronomy Division of the American Astronomical Society (32). https://had.aas.org/sites/had.aas.org/files/HADN32.pdf. Retrieved 10 March 2023.

- ↑ 41.0 41.1 41.2 "Planet and Satellite Names and Discoverers". Gazetteer of Planetary Nomenclature. USGS Astrogeology. https://planetarynames.wr.usgs.gov/Page/Planets.

- ↑ 42.0 42.1 42.2 42.3 42.4 42.5 42.6 42.7 Grav, Tommy; Bauer, James (2007). "A deeper look at the colors of the Saturnian irregular satellites". Icarus 191 (1): 267–285. doi:10.1016/j.icarus.2007.04.020. Bibcode: 2007Icar..191..267G.

- ↑ 43.0 43.1 43.2 Thomas, P. C. (July 2010). "Sizes, shapes, and derived properties of the saturnian satellites after the Cassini nominal mission". Icarus 208 (1): 395–401. doi:10.1016/j.icarus.2010.01.025. Bibcode: 2010Icar..208..395T. http://www.ciclops.org/media/sp/2011/6794_16344_0.pdf. Retrieved 2015-09-04.

- ↑ 44.0 44.1 44.2 44.3 44.4 Jacobson, R. A.; Antreasian, P. G.; Bordi, J. J.; Criddle, K. E.; Ionasescu, R.; Jones, J. B.; Mackenzie, R. A.; Meek, M. C. et al. (December 2006). "The Gravity Field of the Saturnian System from Satellite Observations and Spacecraft Tracking Data". The Astronomical Journal 132 (6): 2520–2526. doi:10.1086/508812. Bibcode: 2006AJ....132.2520J.

- ↑ 45.0 45.1 45.2 45.3 Williams, David R. (August 21, 2008). "Saturnian Satellite Fact Sheet". NASA (National Space Science Data Center). http://nssdc.gsfc.nasa.gov/planetary/factsheet/saturniansatfact.html.

- ↑ 46.0 46.1 46.2 Porco, C. C.; Thomas, P. C.; Weiss, J. W.; Richardson, D. C. (2007). "Saturn's Small Inner Satellites:Clues to Their Origins". Science 318 (5856): 1602–1607. doi:10.1126/science.1143977. PMID 18063794. Bibcode: 2007Sci...318.1602P. http://ciclops.org/media/sp/2007/4691_10256_0.pdf.

- ↑ "A Small Find Near Equinox". NASA/JPL. August 7, 2009. http://saturn.jpl.nasa.gov/photos/imagedetails/index.cfm?imageId=3617.

- ↑ 48.0 48.1 Tiscareno, Matthew S.; Burns, Joseph A; Hedman, Mathew M; Porco, Carolyn C.; Weiss, John W.; Dones, Luke; Richardson, Derek C.; Murray, Carl D. (2006). "100-metre-diameter moonlets in Saturn's A ring from observations of 'propeller' structures". Nature 440 (7084): 648–650. doi:10.1038/nature04581. PMID 16572165. Bibcode: 2006Natur.440..648T.

- ↑ 49.0 49.1 Sremčević, Miodrag; Schmidt, Jürgen; Salo, Heikki; Seiß, Martin; Spahn, Frank; Albers, Nicole (2007). "A belt of moonlets in Saturn's A ring". Nature 449 (7165): 1019–21. doi:10.1038/nature06224. PMID 17960236. Bibcode: 2007Natur.449.1019S.

- ↑ Murray, Carl D. et al. (2008). "The determination of the structure of Saturn's F ring by nearby moonlets". Nature 453 (7196): 739–744. doi:10.1038/nature06999. PMID 18528389. Bibcode: 2008Natur.453..739M. https://hal-cea.archives-ouvertes.fr/cea-00930885/file/mur.pdf.

- ↑ Hedman, M. M.; J. A. Burns; M. S. Tiscareno; C. C. Porco; G. H. Jones; E. Roussos; N. Krupp; C. Paranicas et al. (2007). "The Source of Saturn's G Ring". Science 317 (5838): 653–656. doi:10.1126/science.1143964. PMID 17673659. Bibcode: 2007Sci...317..653H. http://ciclops.org/media/sp/2007/3882_9284_0.pdf.

- ↑ 52.0 52.1 52.2 52.3 52.4 Spitale, J. N.; Jacobson, R. A.; Porco, C. C.; Owen, W. M. Jr. (2006). "The orbits of Saturn's small satellites derived from combined historic and Cassini imaging observations". The Astronomical Journal 132 (2): 692–710. doi:10.1086/505206. Bibcode: 2006AJ....132..692S.

- ↑ 53.0 53.1 53.2 53.3 53.4 53.5 Thomas, P.C et al. (2007). "Shapes of the saturnian icy satellites and their significance". Icarus 190 (2): 573–584. doi:10.1016/j.icarus.2007.03.012. Bibcode: 2007Icar..190..573T. http://www.geoinf.fu-berlin.de/publications/denk/2007/ThomasEtAl_SaturnMoonsShapes_Icarus_2007.pdf.