Comparative Law

From Nwe

From Nwe  |

| Law Articles |

|---|

| Jurisprudence |

| Law and legal systems |

| Legal profession |

| Types of Law |

| Administrative law |

| Antitrust law |

| Aviation law |

| Blue law |

| Business law |

| Civil law |

| Common law |

| Comparative law |

| Conflict of laws |

| Constitutional law |

| Contract law |

| Criminal law |

| Environmental law |

| Family law |

| Intellectual property law |

| International criminal law |

| International law |

| Labor law |

| Maritime law |

| Military law |

| Obscenity law |

| Procedural law |

| Property law |

| Tax law |

| Tort law |

| Trust law |

Comparative law (French: droit comparé, German: Rechtsvergleichung, Italian: diritto comparato, Spanish: derecho comparado, Portuguese: direito comparado, Greek: Συγκριτικό Δίκαιο) is the study of differences and similarities between the laws of different countries. Comparative law is the use of laws wherein no law exists in isolation. Within a world situation, there is a give and take action to create a harmonious and cooperative solution.

As the world becomes smaller in traveling time, and larger in legal discrepancies, comparative law uses the art of estimation by comparison which is a relative comparison between two or more entities.

Purpose of comparative law

Comparative law is an academic study of separate legal systems, each one analyzed in its constitutive elements; how they differ in the different legal systems, and how their elements combine into a system.

Several disciplines have developed as separate branches of comparative law, including comparative constitutional law, comparative administrative law, comparative civil law (in the sense of the law of torts, delicts, contracts and obligations), comparative commercial law (in the sense of business organizations and trade), and comparative criminal law. Studies of these specific areas may be viewed as micro- or macro-comparative legal analysis, i.e. detailed comparisons of two countries, or broad-ranging studies of several countries. Comparative civil law studies, for instance, show how the law of private relations is organized, interpreted and used in different systems or countries.

It appears today the principal purposes of comparative law are:

- to attain a deeper knowledge of the legal systems in effect.

- to perfect the legal systems in effect.

- possibly, to contribute to a unification of legal systems, of a smaller or larger scale.

Comparative law in the world

Comparative laws in the world involve the study of the different legal systems in existence in the world, including the common law, the civil law, socialist law, Islamic law, and Asian law. It includes the description and analysis of foreign legal systems, even where no explicit comparison is undertaken.

Social impact of comparative laws

The importance in societies of comparative law has increased enormously in the present age of internationalism, economic globalization and democratization wherein the knowledge of the different rules of conduct as binding upon its members aids in the understanding to promote a harmony and cooperation beyond all boundaries.

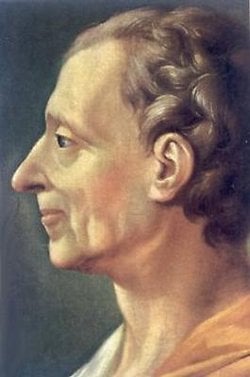

Montesquieu's Comparative law

According to the prevalent view, Charles de Secondat, Baron de Montesquieu is regarded as the 'father' of comparative law. His comparative approach is obvious in the following excerpt from Chapter III of Book I of his masterpiece De l'esprit des lois:

"[The political and civil laws of each nation] should be adapted in such a manner to the people for whom they are framed that it should be a great chance if those of one nation suit another.

They should be in relation to the nature and principle of each government; whether they form it, as may be said of politic laws; or whether they support it, as in the case of civil institutions.

They should be in relation to the climate of each country, to the quality of its soil, to its situation and extent, to the principal occupation of the natives, whether husbandmen, huntsmen, or shepherds: they should have relation to the degree of liberty which the constitution will bear; to the religion of the inhabitants, to their inclinations, riches, numbers, commerce, manners, and customs."

Also, in Chapter XI (entitled 'How to compare two different Systems of Laws') of Book XXIX he advises that

"to determine which of those systems [i.e. the French and English systems for the punishment of false witnesses] is most agreeable to reason, we must take them each as a whole and compare them in their entirety.

Yet another excerpt where Montesqieu's comparative approach is evident is the following one from Chapter XIII of Book XXIX:

As the civil laws depend on the political institutions, because they are made for the same society, whenever there is a design of adopting the civil law of another nation, it would be proper to examine beforehand whether they have both the same institutions and the same political law.

Relationship with other legal fields of study

Comparative law is different from the fields of general jurisprudence (legal theory), international law, including both public international law and private international law (also known as conflict of laws).

Despite the differences between comparative law and these other legal fields, comparative law helps inform all of these areas of normativity. For example, comparative law can help international legal institutions, such as those of the United Nations System, in analyzing the laws of different countries regarding their treaty obligations. Comparative law would be applicable to private international law when developing an approach to interpretation in a conflict’s analysis. Comparative may contribute to legal theory by creating categories and concepts of general application. Comparative law may also provide insights into the problem of legal transplants, namely the transplanting of law and legal institutions from one system to another.

Also, the usefulness of comparative law for sociology, particularly sociology of law (and vice versa) is very large. The comparative study of the various legal systems may show how different legal regulations for the same problem function in practice. Conversely, sociology of law may help comparative law answer questions, such as: How do regulations in different legal systems really function in the respective societies? Are certain legal rules comparable? How do the similarities and differences between legal systems get explained?

Comparative criminal justice is a subfield of the study of Criminal Justice that compares justice systems worldwide. Such study can take a descriptive, historical, or political approach. It is common to broadly categorize the functions of a criminal justice system into policing, adjudication (courts), and corrections, although other categorization schemes exist.

Classifications of legal systems

Arminjon, Nolde, and Wolff[1] believed that, for purposes of classifying the (then) contemporary legal systems of the world, it was required that those systems per se get studied, irrespective of external factors, such as geographical ones. They proposed the classification of legal system into seven groups, or so-called 'families', in particular:

- The French group, under which they also included the countries that codified their law either in nineteenth or in the first half of the twentieth century, using the Napoleonic code civil of year 1804 as a model; this includes countries and jurisdictions such as Italy, Portugal, Spain, Louisiana, states of South America (such as Brazil), Quebec, Santa Lucia, Romania, the Ionian Islands, Egypt, and Lebanon.

- The German group

- The Scandinavian group (comprising the laws of Sweden, Norway, Denmark, Finland, and Iceland)

- The English group (incl. England, the United States, Canada, Australia and New Zealand inter alia)

- The Russian group

- The Islamic group

- The Hindu group

David[2] proposed the classificiation of legal systems, according to the different ideology inspiring each one, into five groups or families:

- Western Laws, a group subdivided into the:

- Romano-Germanic subgroup (comprising those legal systems where legal science got formulated according to Roman Law)

- Anglo-saxon subgroup

- Soviet Law

- Muslim Law

- Hindu Law

- Chinese Law

Especially with respect to the aggregating by David of the Romano-Germanic and Anglo-Saxon Laws into a single family, David argued that the antithesis between the Anglo-Saxon Laws and Romano-German Laws, is of a technical rather than of an ideological nature. Of a different kind is, for instance, the antithesis between (say) the Italian and the American Law, and of a different kind that between the Soviet, Muslim, Hindu, or Chinese Law. According to David, the Romano-Germanic legal systems included those countries where legal science got formulated according to Roman Law, whereas common law countries are those where law got created from the judges.

The characteristics that he believed uniquely differentiate the Western legal family from the other four are:

- liberal democracy

- capitalist economy

- Christian religion

Zweigert and Kötz[3] propose a different, multidimensional methodology for categorizing laws, i.e. for ordering families of laws. They maintain that, in order to determine such families, five criteria should be taken into account, in particular: the historical background, the characteristic way of thought, the different institutions, the recognized sources of law, and the dominant ideology.

Using the aforementioned criteria, they classify the legal systems of the world, in the following six families:

- The Roman family

- The German family

- The Angloamerican family

- The Scandinavian family

- The family of the laws of the Far East (China and Japan)

- The Religious family (Muslim and Hindi law)

Notable personalities

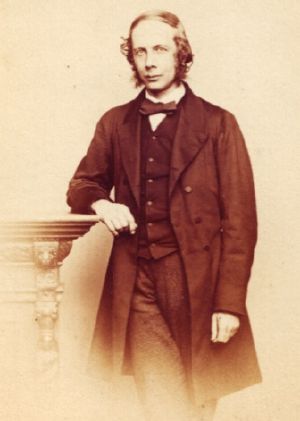

Sir Henry James Sumner Maine (August 15, 1822 – February 3, 1888) was an English comparative jurist and historian, son of Dr James Maine, of Kelso, Borders, Scotland.

He is famous for the thesis, outlined in Ancient Law (1861) that law and society developed "from status to contract." In the ancient world individuals were tightly bound by status to traditional groups, while in the modern one, in which individuals are viewed as autonomous beings, they are free to make contracts and form associations with whomever they choose. Because of this thesis, he can be seen as one of the forefathers of modern sociology of law.

Notes

- ↑ Traité de droit comparé (French) Paris 1950-1952

- ↑ Traité élémentaire de droit civile comparé: Introduction à l'étude des droits étrangers et à la méthode comparative (French) Paris, 1950

- ↑ An Introduction to Comparative Law, translation from the Germany original: T. Weir, 3rd edition; Oxford, 1998.

References

ISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- David, Rene, and John E.C. Brierley. Major legal systems in the world today: an introduction to the comparative study of law. London: the Free Press, Collier-Macmillan, 1968. OCLC 42692

- Moustaira, Elina N. Comparative Law: University Courses (Greek). Ant. N. Sakkoulas Publishers, Athens, 2004.

- Moustaira, Elina N., Milestones in the Course of Comparative Law: Thesis and Antithesis (Greek). Ant. N. Sakkoulas Publishers, Athens, 2003.

- Zimmermann, Reinhard, and Mathias Reimann. The Oxford handbook of comparative law. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2006. ISBN 0-199-29606-5

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.

↧ Download as ZWI file | Last modified: 02/03/2023 21:23:54 | 7 views

☰ Source: https://www.newworldencyclopedia.org/entry/Comparative_law | License: CC BY-SA 3.0

ZWI signed:

ZWI signed:

KSF

KSF