Andrew Jackson

From Nwe

From Nwe

|

|

|

| Term of office | March 4, 1829 – March 3, 1837 |

| Preceded by | John Quincy Adams |

| Succeeded by | Martin Van Buren |

| Date of birth | March 15, 1767 |

| Place of birth | Waxhaw, South Carolina |

| Date of death | June 8, 1845 |

| Place of death | Nashville, Tennessee |

| Spouse | Rachel Donelson Robards Jackson |

| Political party | Democratic-Republican |

Andrew Jackson, nicknamed Old Hickory, (March 15, 1767 – June 8, 1845) was the first governor of Florida, general of the Battle of New Orleans during the War of 1812, a co-founder of the Democratic Party, and seventh president of the United States. A strong proponent of executive authority—he vetoed more legislation than the first six presidents combined—Jackson was a polarizing populist figure who helped shape the Second Party System of American politics. He was so dominant a political presence that the era of his presidency and that of his successor, his vice-president, Martin van Buren, has come to be known as the Age of Jackson.

Jackson was the first president to rise to the nation's highest office from common frontier origins, and the Spoils System he implemented fortified the party structure by providing federal appointments to ordinary working people. By the time of Jackson's presidency the voting franchise had been extended to virtually all white males and Jackson's Democratic Party positioned itself as the heir of Jefferson and the party of the common man. As the French aristocrat Alexis de Tocqueville famously observed of Jackson's America, "the people reign in the American political world as the Deity does in the universe. They are the cause and the aim of all things; everything comes from them, and everything is absorbed in them."[1]

Jackson's presidency was tested when the South Carolina legislature passed an Ordinance of Nullification declaring a federal tariff invalid in South Carolina. This assertion of states rights against the national government tested the balance of the federal system. Jackson's presidential proclamation against South Carolina led to a compromise, yet the issue would rise with greater import and provide political justification for state legislatures from the South to secede from the Union prior to the American Civil War. The issue of states rights versus the authority of the federal government remains contentious in contemporary debates of social issues relating to marriage statutes, education, and abortion.

Jackson had earlier established a reputation as an Indian fighter in both the Creek War and the First Seminole War, and as president he signed the 1830 Indian Removal Act, which offered Indians land west of the Mississippi in return for evacuation of their tribal lands in the east. When the U.S. Supreme Court found that the state of Georgia did not have jurisdiction over the Cherokees to forcibly remove them, Georgia ignored the decision and began the process of evicting the Cherokees from their traditional lands. Their forced march to vacant land in Oklahoma, known as the Trail of Tears, cost the lives of 25 percent of the Indians. While the march took place after Jackson's presidency, it followed Jackson's policy of relocation. His failure to intervene in defense of the legal rights of Native Americans contradicted his advocacy of federal authority against conflicting claims of states rights.

Early life and military career

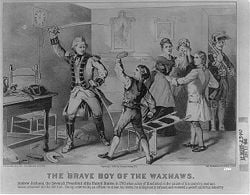

Jackson was born on March 15, 1767 in a backwoods settlement to Presbyterian Scots-Irish immigrants in the Waxhaw area in the Carolinas. He was the youngest of three brothers and was born just a few weeks after his father's death. Both North Carolina and South Carolina have claimed Jackson as a "native son," because the community straddled the state line, and a cousin later claimed that Jackson was born on the North Carolina side. Jackson himself always stated that he was born in a cabin on the South Carolina side, and most historians accept that, since he presumably was repeating the recollections of his mother and others in the immediate family. He received a sporadic education. At age thirteen, he joined the Continental Army as a courier. He was captured and imprisoned by the British during the American Revolutionary War. Jackson was the last president of the United States to have been a veteran of the American Revolution, and the only president to have been a prisoner of war. The war took the lives of Jackson's entire immediate family.

Andrew and his brother Robert Jackson were taken as prisoners, and they nearly starved to death. When Andrew refused to clean the boots of a British officer, the irate redcoat slashed at him, giving him scars on his left hand and head, as well as an intense hatred for the British. Both of them contracted smallpox while imprisoned, and Robert died days after their release. In addition, another of Jackson's brothers and his mother—his entire remaining family—died from war-time hardships that Jackson also blamed upon the British. This anglophobia would help to inspire a distrust and dislike of Eastern "aristocrats," whom Jackson felt were too inclined to favor and emulate their former colonial "masters." Jackson admired Napoleon Bonaparte for his willingness to contest British military supremacy.

Jackson came to Tennessee by 1787. Though he barely read law, he found he knew enough to become a young lawyer on the frontier. Since he was not from a distinguished family, he had to make his career by his own merits; and soon he began to prosper in the rough-and-tumble world of frontier law. Most of the actions grew out of disputed land-claims, or from assaults and battery. He was elected as Tennessee's first congressman upon its statehood in the late 1790s, and quickly became a U.S. Senator in 1797 but resigned within a year. In 1798 he was appointed judge on the Tennessee Supreme Court.[2]

Creek War and War of 1812

Jackson became a colonel in the Tennessee militia, which he had led since the beginning of his military career in 1801. In 1813 Northern Creek Band chieftain Peter McQueen massacred four hundred men, women, and children at Fort Mims (in what is now Alabama). Jackson commanded in the campaign against the Northern Creek Indians of Alabama and Georgia, also known as the "Red Sticks." Creek leaders such as William Weatherford (Red Eagle), Peter McQueen, and Menawa, who had been allies of the British during the War of 1812, violently clashed with other chiefs of the Creek Nation over white encroachment on Creek lands and the "civilizing" programs administered by U.S. Indian Agent Benjamin Hawkins.

In the Creek War, a theatre of the War of 1812, Jackson defeated the Red Stick Creeks at the Battle of Horseshoe Bend. Jackson was aided by members of the Southern Creek Indian Band, who had requested Jackson's aid in putting down what they considered to be the "rebellious" Red Sticks, and some Cherokee Indians, who also sided with the Americans. Eight hundred Northern Creek Band "Red Sticks" Indians were killed in the battle. Jackson spared Weatherford's life from any acts of vengeance. Sam Houston and Davy Crockett, later to become famous themselves in Texas, served under Jackson at this time. Following the victory, Jackson imposed the Treaty of Fort Jackson upon both his Northern Creek enemy and Southern Creek allies, wresting 20 million acres (81,000 square kilometers) from all Creeks for white settlement.

Jackson's service in the War of 1812 was conspicuous for its bravery and success. He was a strict officer, but was popular with his troops. It was said he was "tough as old hickory" wood on the battlefield, which gave him his nickname.

The war, and particularly his command at the Battle of New Orleans on January 8, 1815, made his national reputation. He advanced in rank to major general. In the battle, Jackson's six thousand militiamen behind barricades of cotton bales opposed 12,000 British regulars marching across an open field, led by General Edward Pakenham. The battle was a complete American victory. The British had over two thousand casualties to Jackson's eight killed and 58 wounded or missing.[3]

First Seminole War

Jackson served in the military again during the First Seminole War when he was ordered by President James Monroe in December 1817 [3] to lead a campaign in Georgia against the Seminole and Creek Indians. Jackson was also charged with preventing Spanish Florida from becoming a refuge for runaway slaves. Critics later alleged that Jackson exceeded orders in his Florida actions, but Monroe and the public wanted Florida. Before going, Jackson wrote to Monroe, "Let it be signified to me through any channel... that the possession of the Floridas would be desirable to the United States, and in sixty days it will be accomplished." Monroe gave Jackson orders that were purposely ambiguous, sufficient for international denials.

Jackson's Tennessee volunteers were attacked by Seminoles, but this left their villages vulnerable, and Jackson burned them and their crops. He found letters that indicated that the Spanish and British were "secretly" assisting the Indians. Jackson believed that the United States would not be "secure" as long as Spain and Great Britain encouraged American Indians to fight and argued that his actions were undertaken in "self-defense." Jackson captured Pensacola, Florida with little more than some warning shots and deposed the Spanish governor. He illegally tried, and then captured and executed two British subjects, Robert Ambrister and Alexander Arbuthnot who had been supplying and advising the Indians. Jackson's action also struck fear into the Seminole tribes as word of his ruthlessness in battle spread.

This also created an international incident, and many in the Monroe administration called for Jackson to be censured. However, Jackson's actions were defended by Secretary of State John Quincy Adams. When the Spanish minister demanded a "suitable punishment" for Jackson, Adams wrote back "Spain must immediately [decide] either to place a force in Florida adequate at once to the protection of her territory, ... or cede to the United States a province, of which she retains nothing but the nominal possession, but which is, in fact, ... a post of annoyance to them." Adams used Jackson's conquest, and Spain's own "weaknesses," to convince the Spanish to cede Florida to the United States. Jackson was subsequently named its territorial governor.

Election of 1824

During his first run for the presidency in 1824, Jackson received a plurality of both the popular and electoral votes. Since no candidate received a majority, the election decision was given to the House of Representatives, which chose John Quincy Adams. Jackson denounced it as a "corrupt bargain" because Henry Clay gave his votes to Adams, who then made Clay secretary of state. Jackson later called for abolishing the Electoral College. Jackson's defeat burnished his political credentials, however, since many voters believed the "man of the people" had been robbed by the "corrupt aristocrats of the East."

One of Jackson's enemies, Albert Gallatin, who was a vice presidential candidate in 1824, saw Jackson as "an honest man and the idol of the worshippers of military glory, but from incapacity, military habits, and habitual disregard of laws and constitutional provisions, altogether unfit for the office."

Thomas Jefferson, in retirement, said of Jackson in 1824:

I feel much alarmed at the prospect of seeing General Jackson President. He is one of the most unfit men I know of for such a place. He has had very little respect for laws or constitutions, and is, in fact, an able military chief. His passions are terrible. When I was President of the Senate he was a Senator; and he could never speak on account of the rashness of his feelings. I have seen him attempt it repeatedly, and as often choke with rage. His passions are no doubt cooler now; he has been much tried since I knew him, but he is a dangerous man.[4]

Election of 1828

The United States presidential election of 1828 featured a rematch between incumbent President John Quincy Adams and chief rival Jackson, who was now a candidate under the banner of the new Democratic Party.

The election was marked by an enormous increase in the number of voters, with three times as many people going to the polls as had in 1824. The campaign itself revolved more around personalities than issues. This election brought the start of mudslinging to politics. Jackson's marriage came in for attack: when he had married his wife Rachel, the couple had believed that she was divorced; however, the divorce was not yet finalized, so he had had to remarry her once the legal papers were complete. In the Adams campaign's hands, this became a scandal. Jackson was further accused for his courts martial and execution of deserters, for his massacres of Indian villages, and for his habit of dueling. Adams did not escape attack. Adams was accused of using public funds to buy gambling devices for the presidential residence; it turned out that these were a chess set and a pool table.

Enthusiastic voters, although lacking any clear-cut idea of his views, turned overwhelmingly to Jackson, giving him 56 percent of the popular vote. He carried 15 of the then 24 states, winning 178 electoral votes to 83 for Adams.

Presidency 1829-1837

Spoils system

Jackson is credited for introducing the spoils system, or "patronage," to American politics. The term "spoils system" was introduced in 1832 by Senator William L. Marcy, a career politician from New York State, who proclaimed, "To the victor belong the spoils." Marcy resigned from the senate in 1833 halfway through his term and returned to New York having successfully campaigned to be elected governor of New York.

The spoils system was pioneered by successive New York governors in the early nineteenth century, most notably DeWitt Clinton. At the federal level Thomas Jefferson systematically reviewed the civil list, and list of military officers, when he became president. President John Quincy Adams tried to be nonpartisan in his appointments in 1825, but quickly discovered that caused problems:

On such appointments all the wormwood and gall of the old party hatred ooze out. Not a vacancy to any office occurs but there is a distinguished Federalist started and pushed home as a candidate to fill it, always well qualified, sometimes in an eminent degree, and yet so obnoxious to the Republican party, that they cannot be appointed without exciting a vehement clamor against him and the administration. It becomes thus impossible to fill any vacancy in appointment without offending one half of the community.[5]

After he became president in 1828, Andrew Jackson systematically rewarded his supporters. He considered that popular election gave the victorious party a mandate to select officials from its own ranks. Proponents claimed that ordinary Americans were able to discharge the official duties of government offices; not just a special civil service elite. Opponents considered it vulnerable to incompetence and corruption.

The Third Party System (1854-1896) was the apogee of the spoils system. It was used quite effectively by Abraham Lincoln in supporting both his Republican party and the Union war effort.

Opposition to the National Bank

As president, Jackson worked to take away the federal charter of the Second Bank of the United States. The second Bank had been authorized, during James Madison's tenure in 1816, for a twenty-year period. Jackson opposed the national bank concept on ideological grounds. In Jackson's veto message, the bank needed to be abolished because:

- it was unconstitutional

- it concentrated an excessive amount of the nation's financial strength into a single institution

- it exposed the government to control by "foreign interests"

- it exercised too much control over members of the Congress

- it favored Northeastern states over Southern and Western states

Jackson followed Jefferson as a supporter of the ideal of an "agricultural republic" and felt the bank improved the fortunes of an "elite circle" of commercial and industrial entrepreneurs at the expense of farmers and laborers. After a titanic struggle, Jackson succeeded in destroying the bank by vetoing its 1832 re-charter by Congress and by withdrawing U.S. funds in 1833. The bank's money-lending functions were taken over by the legions of local and state banks that sprang up feeding an expansion of credit and speculation; the commercial progress of the nation's economy was noticeably dented by the resulting failures.

The U.S. Senate censured Jackson on March 27, 1834 for his actions in defunding the Bank of the United States; the censure was later expunged when the Jacksonians had a majority in the Senate.

Nullification crisis

Another notable crisis during Jackson's period of office was the "nullification crisis," or "secession crisis," of 1828–1832, which merged issues of sectional strife with disagreements over tariffs. Critics alleged that high tariffs (the "Tariff of Abominations") on imports of common manufactured goods from Europe made those goods more expensive than ones from the northern U.S., thus raising the prices paid by planters in the southern U.S. Southern politicians thus argued that tariffs benefited northern industrialists at the expense of southern farmers.

The issue came to a head when Vice President John C. Calhoun, in the South Carolina Exposition and Protest of 1828, supported the claim of his home state that it had the right to "nullify"—declare illegal—the tariff legislation of 1828, and more generally the right of a state to nullify any Federal laws which went against its interests. Although Jackson sympathized with the South in the tariff debate, he was also a strong supporter of a strong union, with considerable powers for the central government. Jackson attempted to face Calhoun down over the issue, which developed into a bitter rivalry between the two men. Particularly famous was an incident at the April 13, 1829 Jefferson Day dinner, involving after-dinner toasts. Jackson rose first and voice booming, and glaring at Calhoun, yelled out "Our federal Union: IT MUST BE PRESERVED!," a clear challenge to Calhoun. Calhoun glared at Jackson and yelled out, his voice trembling, but booming as well, "The Union: NEXT TO OUR LIBERTY, MOST DEAR!"

In response to South Carolina's threat, Congress passed a "Force Bill" in 1833, and Jackson vowed to send troops to South Carolina in order to enforce the laws. In December 1832, he issued a resounding proclamation against the "nullifiers," stating: "I consider...the power to annul a law of the United States, assumed by one State, incompatible with the existence of the Union, contradicted expressly by the letter of the Constitution, unauthorized by its spirit, inconsistent with every principle on which it was founded, and destructive of the great object for which it was formed." South Carolina, the President declared, stood on "the brink of insurrection and treason," and he appealed to the people of the state to reassert their allegiance to that Union for which their ancestors had fought. Jackson also denied the right of secession: "The Constitution… forms a government not a league…. To say that any State may at pleasure secede from the Union is to say that the United States is not a nation."

The crisis was resolved when Jackson sent warships to Charleston, South Carolina, and enforced Congress acts through the Force Bill. Tariffs gradually lowered until 1842.

Indian Removal

Perhaps the most controversial aspect of Andrew Jackson's presidency was his policy regarding American Indians. Jackson was a leading advocate of a policy known as "Indian Removal," signing the Indian Removal Act into law in 1830. The Removal Act did not order the removal of any American Indians; it authorized the President to negotiate treaties to purchase tribal lands in the east in exchange for lands further west, outside of existing U.S. state borders. According to biographer Robert V. Remini, Jackson promoted this policy primarily for reasons of national security, seeing that Great Britain and Spain had recruited Native Americans within U.S. borders in previous wars with the United States. According to historian Anthony Wallace, Jackson never publicly advocated removing American Indians by force. Instead, Jackson made the negotiation of treaties priority: nearly seventy Indian treaties—many of them land sales—were ratified during his presidency, more than in any other administration.

The Removal Act was especially popular in the South, where population growth and the discovery of gold on Cherokee land had increased pressure on tribal lands. The state of Georgia became involved in a contentious jurisdictional dispute with the Cherokees, culminating in the 1832 U.S. Supreme Court decision Worcester v. Georgia that ruled that Georgia could not impose its laws upon Cherokee tribal lands. About this case, Jackson is often quoted as having said, "John Marshall has made his decision, now let him enforce it!" Jackson probably never said this; the popular story that Jackson defied the Supreme Court in carrying out Indian Removal is untrue.

Instead, Jackson used the Georgia crisis to pressure Cherokee leaders to sign a removal treaty. A faction of Cherokees led by Jackson's old ally Major Ridge negotiated the Treaty of New Echota with Jackson's administration, a document of dubious legality which was rejected by most Cherokees. However, the terms of the treaty were strictly enforced by Jackson's successor, Martin Van Buren, which resulted in the deaths of thousands of Cherokees along the "Trail of Tears."

In all, more than 45,000 American Indians were relocated to the West during Jackson's administration. During this time, the administration purchased about 100 million acres (400,000 square kilometers) of Indian land for about $68 million and 32 million acres (130,000 square kilometers) of western land. Though the relocation process was generally popular with the American people at the time, it resulted in much suffering and death among American Indians. Jackson was criticized at the time for his role in these events, and the criticism has grown over the years.

On January 30, 1835, an unsuccessful attack occurred in the United States Capitol Building; it was the first assassination attempt made against an American president. Richard Lawrence approached Jackson and fired two pistols, which both misfired. Lawrence was later found to be mentally ill.

Major Presidential acts

- Maysville Road Veto

- Signed Indian Removal Act of 1830

- Vetoed renewal of Second Bank of the United States (1832)

- Signed Force Bill of 1833

- Executive Order: Specie Circular (1836)

Administration and Cabinet

| OFFICE | NAME | TERM |

| President | Andrew Jackson | 1829–1837 |

| Vice President | John C. Calhoun | 1829–1832 |

| Martin Van Buren | 1833–1837 | |

| Secretary of State | Martin Van Buren | 1829–1831 |

| Edward Livingston | 1831–1833 | |

| Louis McLane | 1833–1834 | |

| John Forsyth | 1834–1837 | |

| Secretary of the Treasury | Samuel Ingham | 1829–1831 |

| Louis McLane | 1831–1833 | |

| William Duane | 1833 | |

| Roger B. Taney | 1833–1834 | |

| Levi Woodbury | 1834–1837 | |

| Secretary of War | John H. Eaton | 1829–1831 |

| Lewis Cass | 1831–1836 | |

| Attorney General | John M. Berrien | 1829–1831 |

| Roger B. Taney | 1831–1833 | |

| Benjamin F. Butler | 1833–1837 | |

| Postmaster General | William T. Barry | 1829–1835 |

| Amos Kendall | 1835–1837 | |

| Secretary of the Navy | John Branch | 1829–1831 |

| Levi Woodbury | 1831–1834 | |

| Mahlon Dickerson | 1834–1837 | |

Supreme Court appointments

- John McLean – 1830

- Henry Baldwin – 1830

- James Moore Wayne – 1835

- Roger Brooke Taney (Chief Justice) – 1836

- Philip Pendleton Barbour – 1836

- John Catron – 1837

Major Supreme Court cases

- Cherokee Nation vs. Georgia, 1831

- Worcester v. Georgia, 1832

- Charles River Bridge v. Warren Bridge, 1837

States admitted to the Union

- Arkansas - 1836

- Michigan - 1837

Family and personal life

Jackson met Rachel after her first husband, Colonel Lewis Robards, left her to get a divorce. They fell in love and quickly married. Robards returned two years later without ever having obtained a divorce. Rachel quickly divorced her first husband and then legally married Jackson. This remained a sore point for Jackson who deeply resented attacks on his wife's honor. Jackson fought 103 duels, many nominally over his wife's honor. Charles Dickinson, the only man Jackson ever killed in a duel, had been goaded into angering Jackson by Jackson's political opponents. Nominally fought over a horse-racing debt and an insult to his wife on May 30, 1806, Dickinson shot Jackson in the ribs before Jackson returned the fatal shot. The bullet that struck Jackson was so close to his heart that it could never be safely removed. Jackson had been wounded so frequently in duels that it was said he "rattled like a bag of marbles." At times he would cough up blood, and he experienced considerable pain from his wounds for the rest of his life.

Rachel died of an unknown cause two months prior to Jackson taking office as president. Jackson blamed John Quincy Adams for Rachel's death because the marital scandal was brought up in the election of 1828. He felt that this had hastened her death and never forgave Adams.

Jackson had two adopted sons, Andrew Jackson Jr., the son of Rachel's brother Severn Donelson, and Lyncoya, a Creek Indian orphan adopted by Jackson after the Creek War. Lyncoya died in 1828 at age 16, probably from pneumonia or tuberculosis.

The Jacksons also acted as guardians for eight other children. John Samuel Donelson, Daniel Donelson, and Andrew Jackson Donelson were the sons of Rachel's brother Samuel Donelson who died in 1804. Andrew Jackson Hutchings was Rachel's orphaned grand nephew. Caroline Butler, Eliza Butler, Edward Butler, and Anthony Butler were the orphaned children of Edward Butler, a family friend. They came to live with the Jacksons after the death of their father.

The widower Jackson invited Rachel's niece Emily Donelson to act as his White House hostess and unofficial First Lady. Emily was married to Andrew Jackson Donelson, who acted as Jackson's private secretary. The relationship between the president and Emily became strained during the Petticoat Affair, and the two became estranged for over a year. They eventually reconciled and she resumed her duties as White House hostess. Sarah Yorke Jackson, the wife of Andrew Jackson Jr., became co-hostess of the White House in 1834. It was the only time in history when two women simultaneously acted as unofficial First Lady. Sarah took over all hostess duties after Emily died from tuberculosis in 1836.

Jackson remained influential in both national and state politics after retiring to "The Hermitage," his Nashville home, in 1837. Though a slave-holder, Jackson was a firm advocate of the federal union of the states, and declined to give any support to talk of secession.

Jackson was a lean figure standing at 6 feet, 1 inch (1.85 m) tall, and weighing between 130 and 140 pounds (64 kilograms) on average. Jackson also had an unruly shock of red hair, which had completely grayed by the time he became president at age 61. Jackson was one of the more sickly presidents, suffering from chronic headaches, abdominal pains, and a hacking cough that often brought up blood and sometimes even made his whole body shake. After retiring to Nashville, he enjoyed eight years of retirement and died of chronic tuberculosis and heart failure at the Hermitage on June 8, 1845, at the age of 78. His last words were: "Oh, do not cry. Be good children, and we shall all meet in Heaven."

In his will, Jackson left his entire estate to his adopted son, Andrew Jackson Jr., except for specifically enumerated items that were left to various other friends and family members. Jackson left several slaves to his daughter-in-law and grandchildren. Jackson left a sword to his grandson, with the injunction, "that he will always use it in defence of our glorious Union."

Memorials and movies

- Memorials to Jackson include a set of three identical equestrian statues located in different parts of the country. One is in Jackson Square in New Orleans, Louisiana. Another is in Nashville on the grounds of the Tennessee State Capitol. The other is in Washington, D.C., near the White House.

- Numerous counties and cities are named after him, including Jacksonville, Florida; Jackson, Michigan; Jackson; Mississippi, Jackson, Tennessee; Jackson County, Florida; and Jackson County, Missouri.

- Jackson's portrait appears on the American $20 bill. He has appeared on $5, $10, $50, and $10,000 bills in the past, as well as a Confederate $1,000 bill.

- Jackson's image is on the Blackjack postage stamp.

Notes

- ↑ American President: President Andrew Jackson: The American Franchise[1] retrieved November 19, 2007

- ↑ "Andrew Jackson" [2] virtualwarmuseum. Retrieved September 6, 2008.

- ↑ Andrew Jackson, A brief biography, A National Hero, the Battle of New Orleans Retrieved September 6, 2008.

- ↑ Paul Leicester Ford. The Writings of Thomas Jefferson. 10 vols. (New York, 1892-1899. Vol 10, 331).

- ↑ Josiah Quincy. 1858. Memoir of the Life of John Quincy Adams. Scholarly Publishing Office, University of Michigan Library, 2005), 148.

References

ISBN links support NWE through referral fees

Primary sources

- Bassett, John Spencer, ed. Correspondence of Andrew Jackson. Washington, DC: Carnegie Institution of Washington, 1926-1935.

- Smith, Sam B., and Harriet Fason Chappell Owsley, eds. Papers of Andrew Jackson. Knoxville, TN: University of Tennessee Press, 1980-2002. Moser, Harold D., Sharon MacPherson, and Charles F. Bryan Jr. (eds). Vols. 2-4. ISBN 0870492195 (v. 1); ISBN 0870494414 (v. 2); ISBN 0870496506 (v. 3); ISBN 0870497782 (v. 4); ISBN 0870498975 (v. 5).

- Online speeches and presidential messagesAvalon Project at Yale Law School. Retrieved September 6, 2008.

Secondary sources

- Brands, H. W. 2005. Andrew Jackson: His Life and Times. New York: Random House Large Print. ISBN 9780375435447. Biography emphasizing military career.

- Brustein, Andrew. 2003. The Passions of Andrew Jackson. New York: Alfred A. Knopf. ISBN 0375414282

- Bugg Jr., James L. (ed). 1962. Jacksonian Democracy: Myth or Reality? New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston. Excerpts from scholars.

- Gammon, Samuel Rhea. 1971. The Presidential Campaign of 1832. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press. ISBN 0837148278

- Hammond, Bray. 1957. “Andrew Jackson's Battle with the "Money Power," Ch. 8 in Banks and Politics in America: From the Revolution to the Civil War. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. Pulitzer Prize winner.

- Hofstatder, Richard. 1948. The American Political Tradition. New York: Vintage Books, 1974. ISBN 0394700090. Contains a chapter on Jackson.

- James, Marquis. 1938. The Life of Andrew Jackson. Indianapolis, NY: The Bobbs-Merrill Company. Combines two books: The Border Captain and Andrew Jackson: Portrait of a President; winner of the Pulitzer Prize for Biography.

- Latner Richard B. 1979. The Presidency of Andrew Jackson: White House Politics, 1820-1837 Athens, GA: University of Georgia Press. ISBN 0820304573

- Ogg, Frederic Austin. 2002. The Reign of Andrew Jackson: A Chronicle of the Frontier in Politics. Washington, DC: Ross and Perry, Inc. ISBN 1932109021 short survey online at Gutenberg

- Ratner, Lorman A. 1997. Andrew Jackson and His Tennessee Lieutenants: A Study in Political Culture. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press. ISBN 0313299587

- Remini, Robert V. 2003. The Life of Andrew Jackson. Newtown, CT: American Political Biography Press. ISBN 0945707347

- Andrew Jackson and the Course of American Empire, 1767-1821. 1977. New York: Harper & Row. ISBN 0060135743

- Andrew Jackson and the Course of American Freedom, 1822-1832. 1981. New York: Harper & Row. ISBN 0060148446

- Andrew Jackson and the Course of American Democracy, 1833-1845. 1984. New York: Harper & Row. ISBN 0060152796

- Remini, Robert V. 1988. The Legacy of Andrew Jackson: Essays on Democracy, Indian Removal, and Slavery. Baton Rouge, LA: Louisiana State University Press. ISBN 0807114073

- Rowland, Dunbar. 1971. Andrew Jackson's Campaign against the British, or, the Mississippi Territory in the War of 1812, concerning the Military Operations of the Americans, Creek Indians, British, and Spanish, 1813-1815. Freeport, NY: Books for Libraries Press. ISBN 0836956370

- Schlesinger Jr., Arthur M. 1945. The Age of Jackson. Boston, MA: Little, Brown and Company. Winner of the Pulitzer Prize for History.

- Schouler, James. History of the United States of America: Under the Constitution. New York: Dodd, Mead & Company. 1894-1913; Vol. 4, 1831-1847. Democrats and Whigs.online edition

- Taylor, George Rogers (ed). 1949. Jackson Versus Biddle: The Struggle over the Second Bank of the United States Boston: Heath. Excerpts from primary and secondary sources.

- Syrett, Harold C. 1953. Andrew Jackson: His Contribution to the American Tradition. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 1971. ISBN 0837158028

- Wallace, Anthony F. C. 1993. The Long, Bitter Trail: Andrew Jackson and the Indians. New York : Hill and Wang. ISBN 0809066319

- Ward, John William. 1955. Andrew Jackson, Symbol for an Age. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Wilentz, Sean. 2005. Andrew Jackson. New York: Times Books. ISBN 9780805069259. A short biography, stressing Indian removal and slavery issues.

External links

All links retrieved June 19, 2021.

- Inaugural addresses

- State of the Union addresses

- First State of the Union Address

- Second State of the Union Address

- Third State of the Union Address

- Fourth State of the Union Address

- Fifth State of the Union Address

- Sixth State of the Union Address

- Seventh State of the Union Address

- Eighth State of the Union Address

| Preceded by: (none) |

United States Representatives 1796 – 1797 |

Succeeded by: William C. C. Claiborne |

| Preceded by: William Cocke |

United States Senator (Class 1) from Tennessee 1797 – 1798 |

Succeeded by: Daniel Smith |

| Preceded by: (none) |

Military Governor of Florida 1821 |

Succeeded by: William P. Duval |

| Preceded by: John Williams |

United States Senator (Class 2) from Tennessee 1823 – 1825 |

Succeeded by: Hugh Lawson White |

| Preceded by: James Monroe |

Democratic-Republican Party presidential nominee 1824 (lost)(a) |

Succeeded by: (none) |

| Preceded by: (none) |

Democratic Party presidential nominee 1828 (won), 1832 (won) |

Succeeded by: Martin Van Buren |

| Preceded by: John Quincy Adams |

President of the United States March 4 1829 – March 3 1837 |

Succeeded by: Martin Van Buren |

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.

↧ Download as ZWI file | Last modified: 02/03/2023 19:42:28 | 25 views

☰ Source: https://www.newworldencyclopedia.org/entry/Andrew_Jackson | License: CC BY-SA 3.0

ZWI signed:

ZWI signed:

KSF

KSF