Washington Monument

From Nwe

From Nwe | Washington Monument | |

|---|---|

| IUCN Category III (Natural Monument) | |

|

|

|

| Location: | Washington, D.C., United States |

| Area: | 106.01 acres (0.429 km²) |

| Established: | January 31, 1848 |

| Visitation: | 467,550 (in 2005) |

| Governing body: | National Park Service |

The Washington Monument is a large white-colored obelisk at the west end of the National Mall in Washington, D.C. It is a United States Presidential Memorial constructed for George Washington, the first president of the United States and the leader of the revolutionary Continental Army that won independence from the British after the American Revolutionary War.

The monument is made of marble, granite, and sandstone. It was designed by Robert Mills, a prominent American architect of the 1840s. The actual construction of the monument began in 1848, but was not completed until 1884, almost 30 years after the architect's death. This hiatus in construction was due to lack of funds and the intervention of the American Civil War. A difference in shading of the marble (visible approximately 45 m/150 feet up) clearly delineates the initial construction from its resumption in 1876.

Its cornerstone was laid on July 4, 1848; the capstone was set on December 6, 1884; and the completed monument was dedicated on February 21, 1885. It officially opened to the public on October 9, 1888. Upon completion, it became the world's tallest structure at 169 m, a title it inherited from the Cologne Cathedral and held until 1889, when the Eiffel Tower was finished in Paris, France.

The Washington Monument's reflection can be seen in the aptly named Reflecting Pool, a rectangular reflecting pool extending to the west, towards the Lincoln Memorial.

Reverend Sun Myung Moon used this site to pronounce the United States as the Second Israel in an historic gathering of more than 300,000 invited guests and curious onlookers on September 18, 1976. Following the day-long celebration, the city of Washington, D.C. was treated to an immense hour long fireworks display.

History

The motivation for the monument

Alone among the Founding Fathers of the United States, George Washington earned the title "Father of the Country" in recognition of his leadership in the cause of American freedom. Appointed commander of the Continental Army in 1775, he molded a fighting force that won independence from the Kingdom of Great Britain. In 1787, as president of the Constitutional Convention, he helped guide the deliberations to form a government that has lasted for more than two hundred years. Two years later he was unanimously elected the first president of the United States.

Washington defined the presidency and helped develop the relationships among the three branches of government. He established precedents that successfully launched the new government on its course. He refused the trappings of power and veered from monarchical government and traditions and twice, despite considerable pressure to do otherwise, gave up the most powerful position in the Americas. Washington remained ever-mindful of the ramifications of his decisions and actions, for he was a consummate statesman. With this monument the citizens of the United States show their enduring gratitude and respect for his contributions during the early history of the nation.

When the Revolutionary War ended, no man in the United States commanded more respect than Washington. Americans celebrated his ability to win the war despite limited supplies and inexperienced men, and they admired his decision to refuse a salary and accept only reimbursements for his expenses. Their regard increased further when it became known that he had rejected a proposal by some of his officers to make him king of the new country. It was not only what Washington did but the way he did it: Abigail Adams, wife of John Adams, described him as "polite with dignity, affable without familiarity, distant without haughtiness, grave without austerity, modest, wise, and good.”

Washington retired to his plantation at Mount Vernon after the war, but he soon had to decide whether to return to public life. As it became clear the Articles of Confederation had left the federal government too weak to levy taxes, regulate trade, or control its borders, men such as James Madison began calling for a convention that would strengthen its authority. Washington was reluctant to attend, as he had business affairs to manage at Mount Vernon. If he did not go to Philadelphia, however, he worried about his reputation and about the future of the country. He finally decided that, since "to see this nation happy… is so much the wish of my soul," he would serve as one of Virginia's representatives. During the summer of 1787, the other delegates chose him to preside over their deliberations, which ultimately produced the U.S. Constitution.

A key part of the Constitution was the development of the office of president of the United States. No one seemed more qualified to fill that position than Washington, and in 1789 he began the first of his two terms. He used the nation's respect for him to develop respect for this new office, but he simultaneously tried to quiet fears that the president would become as powerful as the king the new country had fought against. He tried to create the kind of solid government he thought the nation needed, supporting a national bank, collecting taxes to pay for expenses, and strengthening the Army and Navy. Though many people wanted him to stay for a third term, in 1797 he again retired to Mount Vernon.

Washington died suddenly two years later. His death produced great sadness, and it restarted attempts to honor him. As early as 1783, the Continental Congress had resolved "That an equestrian statue of George Washington be erected at the place where the residence of Congress shall be established." The proposal called for engraving on the statue which explained it had been erected "in honor of George Washington, the illustrious Commander-in-Chief of the Armies of the United States of America during the war which vindicated and secured their liberty, sovereignty, and independence." Though it was easy to understand why nothing happened while the government lacked a permanent home, there was little progress even after Congress had settled on Washington, D.C. as the new capitol.

Ten days after Washington's death, a Congressional committee recommended a different type of monument. John Marshall, a representative from Virginia who would soon become chief justice of the Supreme Court, proposed that a tomb be erected within the capitol. But a lack of funds, disagreement over what type of memorial would best honor the country's first president and the Washington family's reluctance to move his body prevented progress on any project. Inaction would prove typical in the coming years.

Design

Progress towards a memorial finally began in 1833. That year, which marked the 100th anniversary of Washington's birth, a large group of concerned citizens formed the Washington National Monument Society. They began collecting donations, much in the way Blodgett had suggested. By the middle of the 1830s, they had raised over $28,000 and announced a competition for the design of the memorial.

On September 23, 1835, the board of managers of the Society described their expectations:

It is proposed that the contemplated monument shall be like him in whose honor it is to be constructed, unparalleled in the world, and commensurate with the gratitude, liberality, and patriotism of the people by whom it is to be erected… [It] should blend stupendousness with elegance, and be of such magnitude and beauty as to be an object of pride to the American people, and of admiration to all who see it. Its material is intended to be wholly American, and to be of marble and granite brought from each state, that each state may participate in the glory of contributing material as well as in funds to its construction.

The society held a competition for designs in 1836. The winner, architect Robert Mills, was well-qualified for the commission. In 1814, the citizens of Baltimore had chosen him to build a monument to Washington, and he had designed a tall Greek column surmounted by a statue of the president. Mills also knew the capital well, having just been chosen Architect of Public Buildings for Washington.

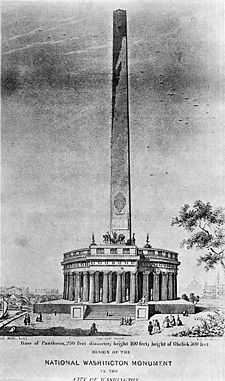

His design called for a 600-foot (183 meter-) tall obelisk—an upright, four-sided pillar that tapers as it rises—with a nearly flat top. He surrounded the obelisk with a circular colonnade, the top of which would feature Washington standing in a chariot. Inside the colonnade would be statues of 30 prominent Revolutionary War heroes.

Yet criticism of Mills' design and its estimated price tag of more than $1 million caused the society to hesitate. In 1848 its members decided to start building the obelisk and to leave the question of the colonnade for later. They believed that if they used the $87,000 they had already collected to start work, the appearance of the monument would spur further donations that would allow them to complete the project.

About this time Congress donated 37 acres (150,000 square meters) of land for the project. The spot Pierre Charles L'Enfant had chosen (now marked by Jefferson Pier) was swampy and unstable, making it unsuitable for supporting what would be an enormously heavy structure. The new location was slightly south and east of the original but still offered many advantages. It "presents a beautiful view of the Potomac," wrote a member of the society, and "is so elevated that the monument will be seen from all parts of the surrounding country." Because it is public land, he continued, "it is safe from any future obstruction of the view… [and it] would be in full view of Mount Vernon, where rests the ashes of the chief."

Construction

Excavation for the foundation of the Washington Monument began in spring 1848. The cornerstone was laid as part of an elaborate Fourth of July ceremony hosted by the Freemasons, a worldwide fraternal organization to which Washington belonged and that still exists. Speeches that day showed the country continued to revere Washington. One celebrant noted, "No more Washingtons shall come in our time ... But his virtues are stamped on the heart of mankind. He who is great in the battlefield looks upward to the generalship of Washington. He who grows wise in counsel feels that he is imitating Washington. He who can resign power against the wishes of a people, has in his eye the bright example of Washington."

Construction continued until 1854, when donations ran out. The next year, Congress voted to appropriate $200,000 to continue the work but changed its mind before the money could be spent. This reversal came about because of a new policy the society had adopted in 1849. It had agreed, after a request from some Alabama residents, to encourage all states and territories to donate memorial stones that could be fitted into the interior walls. Members of the society believed this practice would make citizens feel they had a part in building the monument, and it would cut costs by limiting the amount of stone that had to be bought.

Blocks of marble, granite and sandstone steadily appeared at the site. American Indian tribes, professional organizations, societies, businesses and foreign nations donated stones that were four feet by two feet by 12-18 inches (1.2 by 0.6 by 0.3 to 0.5 m). Many, however, carried inscriptions irrelevant to a memorial for George Washington. For example, one from the Templars of Honor and Temperance stated "We will not buy, sell, or use as a beverage, any spiritous or malt liquors, wine, cider, or any other alcoholic liquor."

It was just one memorial stone that started the events that stopped the Congressional appropriation and ultimately construction altogether. In the early 1850s, Pope Pius IX contributed a block of marble. In March 1854, members of the anti-Catholic, nativist American Party—better known as the "Know-Nothings"—allegedly stole the Pope's stone as a protest and threw it into the Potomac. Then, in order to make sure the monument fit their definition of "American," the Know-Nothings conducted a fraudulent election so they could take over the entire society.

Congress immediately rescinded its $200,000 contribution. The Know-Nothings retained control of the society until 1858, adding 13 courses of the masonry to the Monument—all of which was of such poor quality it later was removed. Unable to collect enough money to finish work, they increasingly lost public support. The Know-Nothings eventually gave up and returned all records to the original society, but the halt in construction continued into and immediately after the Civil War. The bottom third of the monument is a slightly different color than the rest. When construction resumed after the Civil War, the builders were unable to find the same quarry stone used earlier.

Interest in the monument grew after the Civil War ended. Engineers studied the foundation several times to see whether it remained strong enough. In 1876 the centennial of the Declaration of Independence, Congress agreed to appropriate another $200,000 to resume construction. The monument, which had stood for nearly 20 years at less than one-third of its proposed height, now seemed ready for completion.

Before work could begin again, however, arguments about the most appropriate design resumed. Many people thought a simple obelisk—one without the colonnade—would be too bare. Architect Mills was reputed to have said omitting the colonnade would make the monument look like "a stalk of asparagus." Another critic said it offered "little … to be proud of."

This attitude led people to submit alternative designs. Both the Washington National Monument Society and Congress held discussions about how the monument should be finished. The society considered five new designs, concluding that the one by William Wetmore Story seemed "vastly superior in artistic taste and beauty." Congress deliberated over the five designs as well as Mills' original. While deciding, it ordered work on the obelisk to continue. Finally, the members of the society agreed to abandon the colonnade and alter the obelisk so it conformed to classical Egyptian proportions.

Construction resumed in 1879 under the direction of Lieutenant Colonel Thomas Lincoln Casey of the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers. Casey redesigned the foundation, strengthening it so it could support a structure that ultimately weighed more than 40,000 tons. He then followed the society's orders and figured out what to do with the memorial stones that had accumulated. Though many people ridiculed them, Casey managed to install all 193 stones in the interior walls.

The building of the Monument proceeded quickly now that Congress had provided sufficient funding. In four years it was finally completed, with the 3,300 pound (1.5 metric ton) marble capstone put in place on December 6, 1884, during another elaborate dedication ceremony. It opened to the public on October 9, 1888.

Later history

At the time of its construction it was the tallest building in the world. It is still the tallest building in Washington D.C., and due to a 1910 law restricting new buildings' height to be no more than 20 feet (6 meters) greater than the width of the street they're on, it probably always will be (there is a popular misconception that the law specifies that no building may be taller than the Washington Monument, but in fact the law makes no mention of it). Ordinary antique obelisks were seldom taller than around 100 feet (30 meters), making this monument vastly taller than the obelisks around the capitals of Europe and in Egypt.

The Washington Monument drew enormous crowds even before it officially opened. During the six months that followed its dedication, 10,041 people climbed the 893 steps to the top. After the elevator that had been used to raise building materials was altered so that it could carry passengers, the number of visitors grew rapidly. As early as 1888, an average of 55,000 people a month went to the top, and today the Washington Monument has more than 800,000 visitors each year. As with all historic areas administered by the National Park Service, the national memorial was listed on the National Register of Historic Places on October 15, 1966.

On July 4, 2005, a $15 million security and landscaping enhancement project was completed. The design, an innovative and subtle series of concentric circles 30 inches (0.76 meters) high, is designed to make it impossible to drive up to the monument, though approaching on foot or on bicycle should be unimpeded. In addition to the security upgrade, the construction, which required the monument to be closed starting in September 2004, also included an upgrade to the external lighting of the monument.

Construction details

The completed monument stands 555 feet, 5⅛ inches (169.29 meters) tall, with the following construction materials and details:

- Phase One (1848 to 1858): To the 152 foot (46 meter) level, under the direction of Superintendent William Daugherty

-

- Exterior: White marble from Texas, Maryland

- Exterior: White marble, four courses or rows, from Sheffield, Massachusetts

- Phase Two (1878 to 1888): Work completed by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, commanded by Lt. Col. Thomas L. Casey.

-

- Exterior: White marble from another Cockeysville quarry

- Interior: Granite from Maine

- Cap is made from aluminum, at the time a rare metal, valued about the same as silver. The cap was forged by William Frishmuth.

Inscriptions

The four faces of the pyramidal point all bear inscriptions:

| North Face | West Face | South Face | East Face |

|---|---|---|---|

| JOINT COMMISSION AT SETTING OF CAPSTONE. CHESTER A. ARTHUR. W. W. CORCORAN, Chairman. M. E. BELL. EDWARD CLARK. JOHN NEWTON. Act of August 2, 1876. |

CORNER STONE LAID ON BED OF FOUNDATION JULY 4, 1848. FIRST STONE AT HEIGHT OF 152 FEET LAID AUGUST 7, 1880. CAPSTONE SET DECEMBER 6, 1884. |

CHIEF ENGINEER AND ARCHITECT, THOS. LINCOLN CASEY, COLONEL, CORPS OF ENGINEERS.foundhere Assistants: GEORGE W. DAVIS, CAPTAIN, 14TH INFANTRY, BERNARD R. GREEN, CIVIL ENGINEER. Master Mechanic. P. H. MCLAUGHLIN. | LAUS DEO. Praise be to God (Latin) |

The cost of the monument was $1,187,710.23

Exterior structure===

- Total height of monument:

555 feet 5⅛ in (169.294 meters) - Height from lobby to observation level:

500 feet (152 meters) - Width at base of monument:

55 feet 1.5 inches (16.80 meters) - Width at top of shaft:

34 feet 5 in (10.5 meters) - Thickness of monument walls at base:

15 feet (4.6 meters) - Thickness of monument walls at observation level:

18 inches (460 millimeters) - Total weight of monument:

90,854 tons (82,421 metric tons) - Total number of blocks in monument:

36,491

The capstone

- Capstone weight:

3,300 pounds (1.5 tons) - Capstone cuneiform keystone measures 5.16 feet (1.57 meters) from base to the top

- Each side of the capstone base: 3 feet (914 millimeters)

- Width of aluminum tip: 5.6 inches (142 millimeters) on each of its four sides

- Height of aluminum tip at base:

8.9 inches (226 millimeters) - Weight of aluminum tip on capstone:

100 ounces (2.8 kilograms)

Foundation

- Depth of foundation:

36 feet, 10 inches (11.23 meters) - Weight of foundation:

36,912 short tons (33,486 metric tons) - Area of foundation:

16,001 square feet (1487 square meters)

Interior

- Number of memorial stones in stairwell: 199

- Present elevator installed: 1998

- Present elevator cab installed: 2001

- Elevator travel time: One minute

- Number of steps in stairwell: 897

References

ISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Allen, Thomas B. The Washington Monument: It Stands for All. New York: Discovery Books, 2000. ISBN 9781563319211

- Berard, Jim. The Flying Cat and Other Amazing Stories of the Washington Monument. Delaplane, VA: EPM Publications, 2000.

- Doherty, Craig A., and Katherine M. Doherty. The Washington Monument. Woodbridge, CT: Blackbirch Press, 1995. ISBN 9781889324203

- Freidel, Frank Burt, and Lonnelle Aikman. George Washington: Man and Monument. Washington, DC: Washington National Monument Association, 1988. ISBN 9780929050010

- Hargrove, Julia, and Gary Mohrman. Washington Monument: Historic Monuments. Carthage, IL: Teaching & Learning Co., 2001. ISBN 9781573102841

- Mudd, Roger. The Presidential Memorials: Great American Monuments. A&E Home Video, 1994. ISBN 9781565016415

External links

All links retrieved June 6, 2020.

- Washington Monument – National Park Service

- Washington Monument Fast Facts – "Washington Post

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.

↧ Download as ZWI file | Last modified: 02/03/2023 23:37:31 | 10 views

☰ Source: https://www.newworldencyclopedia.org/entry/Washington_Monument | License: CC BY-SA 3.0

ZWI signed:

ZWI signed:

KSF

KSF